Abstract

In current study, the effects of Iranian rice cooking method (Kateh) on residue levels of 41 pesticides were investigated. The pesticides were selected according to Iranian National Standards Organization (INSO) regulations and covered 18 permitted and 23 banned pesticides belonging to different chemical classes such as organophosphate, triazole, and carbamate. A 250 g portion of rice sample was soaked in 2.5 L spiked tap water containing studied pesticides at final concentration 2 μg/mL and then, the effects of washing and cooking were investigated. The pesticides were analyzed simultaneously in a single run using positive electrospray ionisation with multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) after extraction with QuEChERS method. The results showed that washing removed different portions of pesticide residues in the range between 12.0-88.1%. Washing effect was not associated with the water solubility of the pesticides but amount of residue binding to rice matrix was a major factor for residue reduction. In Iranian method of rice preparation, cooking process includes boiling and steam cooking. In this study, the amount of the pesticide residues was decreased in the range of 20.7-100%. Under these conditions, volatilization, hydrolysis, and thermal degradation caused the reduction of the pesticide residues.

Key Words: Cooking process, Pesticide residues, Multi-residue analysis, LC–MS/MS, Rice

Introduction

Rice as a cereal crop, is the most important and principal staple food for a large group of the human population in the world. Rice is the major source of energy in 17 countries in Asia and the Pacific, nine countries in North and South America and eight countries in Africa. More than 3.5 billion people depend on rice for survival and it supplies 20% of the calories consumed worldwide. Although rice alone cannot supply all of the nutrients necessary for adequate nutrition, but it is a good source of thiamine, riboflavin, niacin, glutamic and aspartic acid. Unmilled rice contains a significant amount of dietary fiber (1). Botanically, rice is an annual plant and belongs to the genus Oryza that includes about 22 species. Only two species of rice are considered important as food species for humans and cultivated in the world: Oryza sativa is grown worldwide and Oryza glaberrima grown in parts of West Africa (2). In the recent decades, rice production has increased and according to FAO data, global production of rice has risen steadily from about 215 million tons of paddy rice in 1961 to over 738 million tons in 2012 (3).

The use of pesticides, like pre and post-emergence herbicides, insecticides, and fungicides during various stages of cultivation is one of the most important factors associated with growing in rice production. However, the use of these pesticides affects the whole system of rice: the soil, water, and rice grain. In addition to commonly used pesticides, presence of banned pesticides in rice is another important challenge (4). Nowadays, appearance of pesticide residues in human foods including rice is a great challenge in food safety. Pesticides cause public concern due to their potential adverse effects on human health, which is most obvious in the developing fetus and young child (5). The most common route of exposure to pesticides is ingestion of treated food commodities containing residues. To ensure the safety of food for consumers, numerous legislations such as the EU directives (6) or the Iranian regulation (7), have established maximum residue limits (MRL) for pesticides in foodstuffs. Therefore, control and management of pesticide residues in foods, according to regulations require powerful analytical methods. For these reasons there is a clear need to develop fast methods for the multi-residue analysis of the most commonly used and banned pesticides in rice crops.

Although various techniques based on GC and LC methods coupled to the different detectors such as electron capture detector (ECD), nitrogen-phosphorus detector (NPD) and mass spectrometry detector (MS) have been developed for determination of pesticides residues in rice (8, 9), most of the are suitable for analysis of raw rice samples. Rice is cooked in different methods by boiling, steaming, or in a microwave oven around the world (10). Therefore, food safety investigators are interested to study the effects of cooking processes in pesticide residue levels in rice.

Previous studies in different commodities showed that cooking processes reduced pesticide levels in home and industrial food preparation. In 2002, Lalah and Wandiga studied the effect of boiling on the removal of persistent malathion residues from cooked beans and maize. The results showed that malathion and its polar metabolites, malathion-α and malathionβ-monocarboxylic acids were completely removed by boiling, but malaoxon was not eliminated and still detected in high levels in the solvent extracts of cooked beans and maize (11). Effects of cooking in a microwave oven on elimination of trifluralin, chlorpyrifos, decamethrin, cypermethrin and dichlorvos in rice and beans were studied. The spiked rice and beans samples, at levels of 1.0 mg/kg, were cooked at powers of 500 W and 800 W for 15- 45 min, respectively. After cooking, the levels of spiked pesticides were decreased from 92% to 99% in both rice and beans samples (12). Shoeibi et al. investigated the effect of cooking on removal of three carbamates including carbaryl, propoxur and pirimicarb on spiked rice samples. The levels of pesticides reduced 78%, 55%, and 35% for carbaryl, propoxur, and pirimicarb, respectively, after cooking (13). Another study showed that combination of heat and water in house and industrial processing, dramatically reduced the levels of four fungicides includings, boscalid, mancozeb, iprodione, and propamocarb and insecticide deltamethrin in spinach (14). Angel Yang et al. monitored 44 multi-class pesticides in 31 different food materials using QuEChERS extraction and LC-MS/MS method. In nine samples including colored rice, glutinous rice (white rice), glutinous rice (unpolished rice), green chili, ginger, butterbur, chinamul, spinach, and perilla leaf, 8 pesticides including acetamiprid, azoxystrobin, fenobucarb, fosthiazate, iprobenfos, lufenuron, propiconazole, and trifloxystrobin were detected. After cooking and washing the positive samples, residue levels of mentioned compounds were considerably decreased (15).

The above mentioned studies confirmed that various cooking methods and in house preparation of foods can decrease the residue levels of some pesticides. Therefore, it is necessary to determine the reduction of other pesticide residues in different commodities that are processed in various methods all over the world. In the present study, we investigated the effects of the Iranian traditional in house method for rice cooking (Kateh) on reduction of 41 multi-class pesticide residues using QuEChERS extraction-based LC-ESI-MS/MS technique

Experimental

Chemicals

Pesticides reference standards (purity > 96.0%), triphenylphosphate (TTP) as internal standard, and anhydrous magnesium sulfate (MgSO4) were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich/Fluka/Riedel-de-Haën (Germany). Ammonium formate, methanol (MeOH) and HPLC-grade acetonitrile (MeCN) were purchased from Acros (Belgium). Ethyl acetate (EtAc), glacial acetic acid (HOAc), and sodium acetate were supplied from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). Bondesil-primary secondary amine (PSA, 40 μm) was provided from Interchim (France). HPLC grade water was obtained by purifying demineralized water on a Milli-Q Plus ultra-pure water system (Millipore, Molsheim, France).

Individual stock solutions of pesticides at a concentration of 1000 μg/mL were prepared in ethyl acetate (and methanol for Cartap and Fuberidazole) according to their solubility at 20 °C. A mixed intermediate standard solution at a concentration of 5 μg/mL was prepared via appropriate dilution of the stock solutions in MeOH containing 0.1% HOAc in order to avoid the degradation of the pesticides (8). This solution was used as a spiking solution for validation experiments. Matrix-matched multi-level calibration standards solutions were prepared using sample extracts obtained from organic rice. Aliquots of blank samples (5 mL of final MeCN layer), which were extracted via QuEChERS method were evaporated and reconstituted in 5 mL of mixture of appropriate working standard solutions and 0.02% HOAc in MeOH to generate final concentrations of 0.02, 0.04, 0.10, 0.20, 0.50, and 1.0 mg/kg for the matrix-matched calibration standards. A stock solution of triphenylphosphate (TTP) in ethyl acetate at concentration of 20 μg/mL was used as internal standard and an aliquot of 50 μL of TTP solution in ethyl acetate (20 μg/mL) was added to the spiked rice sample.

Pesticide selection

The 18 selected LC-amenable pesticides (carbaryl, cartap, chlorpyrifos, cinosulfuron, diazinon, edifenphos, malathion, oxadiazon, oxydemeton-methyl, primiphos-methyl, propiconazole, Spinosyn A and D, thiobencarb, thiophanate-methyl, triadimenol, tricyclazole, triflumizole) are used for rice production in Iran and MRLs have been established for them by Iranian National Standard Organization (INSO), NO.13120 (7). According to the regulation, some pesticides are banned to be used in Iran. Existence of banned pesticides in any kind of food including rice can produce health problems and it is necessary to investigate the presence of them in foods. Therefore, 23 banned LC-amenable pesticides according to INSOʼs list (5), including azinphos-ethyl, bromacil, carbofuran, chlorbromuron, chlorfenvinphos, coumaphos, dialifos, dicrotophos, etrimfos, fluometuron, fuberidazole, iprobenfos, methabenzthiazuron, methidathion, monocrotophos, omethoate, phosphamidon, phoxim, propoxur, pyrazophos, TCMTB, tri-allate, and triazophos were selected.

The comprehensive list covers 41 pesticides with different modes of action such as herbicides, fungicides, insecticides and plant growth regulators with different chemical natures such as organophosphates, carbamates, Spinosyn A and D, strobilurins, and quaternary ammoniums (Table 1).

Table 1.

Names, molar masses, MRM parameters, ion ratios and retention times of the studied pesticides for LC-MS/MS analysis

| No. | Pesticides | Molar mass | Precursor ion | CV (V) | 1st Transition (quantitation) | CE (eV) | 2nd Transition (confirmation) | CE (eV) | Rt (min) | Ion ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Azinphos-ethyl | 345 | (M+H)+ | 15 | 346⟶77 | 36 | 346⟶132 | 30 | 18.99 | 1.43 |

| 2 | Bromacil | 261 | (M+H)+ | 20 | 261⟶205 | 12 | 261⟶188 | 35 | 13.75 | 7.03 |

| 3 | Carbaryl | 201 | (M+H)+ | 15 | 202⟶145 | 20 | 202⟶117 | 10 | 14.61 | 3.85 |

| 4 | Carbofuran | 221 | (M+H)+ | 15 | 222⟶165 | 16 | 222⟶123 | 16 | 15 | 1.4 |

| 5 | Cartap | 237 | (M+H)+ | 27 | 238⟶73 | 16 | 238⟶150 | 16 | 2.57 | 1.75 |

| 6 | Chlorbromuron | 292 | (M+H)+ | 28 | 293⟶204 | 16 | 293⟶182 | 16 | 18.47 | 1.3 |

| 7 | Chlorfenvinphos | 358 | (M+H)+ | 28 | 359⟶99 | 28 | 359⟶155 | 17 | 21.05 | 2.11 |

| 8 | Chlorpyrifos | 350 | (M+H)+ | 30 | 350⟶97 | 25 | 350⟶198 | 22 | 25.24 | 2.08 |

| 9 | Cinosulfuron | 413 | (M+H)+ | 16 | 414⟶183 | 15 | 414⟶157 | 15 | 7.06 | 17.9 |

| 10 | Coumaphos | 362 | (M+H)+ | 35 | 363⟶307 | 17 | 363⟶289 | 25 | 20.95 | 3.23 |

| 11 | Dialifos | 393 | (M+H)+ | 20 | 394⟶187 | 10 | 394⟶208 | 15 | 22.77 | 1.12 |

| 12 | Diazinon | 304 | (M+H)+ | 29 | 305⟶97 | 35 | 305⟶169 | 20 | 21.92 | 1.88 |

| 13 | Dicrotophos | 237 | (M+H)+ | 26 | 238⟶112 | 10 | 238⟶193 | 10 | 4.32 | 3.34 |

| 14 | Edifenphos | 310 | (M+H)+ | 30 | 311⟶109 | 32 | 311⟶111 | 26 | 20.5 | 4.85 |

| 15 | Etrimfos | 292 | (M+H)+ | 35 | 293⟶125 | 25 | 293⟶265 | 18 | 21.67 | 2.66 |

| 16 | Fluometuron | 232 | (M+H)+ | 30 | 233⟶72 | 18 | 233⟶46 | 20 | 15.33 | 4.87 |

| 17 | Fuberidazole | 184 | (M+H)+ | 42 | 185⟶157 | 25 | 185⟶156 | 32 | 12.21 | 2.24 |

| 18 | Iprobenfos | 288 | (M+H)+ | 20 | 289⟶91 | 18 | 289⟶205 | 14 | 20.19 | 6.68 |

| 19 | Malathion | 330 | (M+H)+ | 18 | 331⟶127 | 12 | 331⟶99 | 20 | 18.43 | 1.44 |

| 20 | Methabenzthiazuron | 221 | (M+H)+ | 28 | 222⟶165 | 20 | 222⟶150 | 30 | 15.53 | 2.16 |

| 21 | Methidathion | 302 | (M+H)+ | 18 | 303⟶145 | 20 | 303⟶85 | 10 | 16.93 | 1.23 |

| 22 | Monocrotophos | 223 | (M+H)+ | 26 | 224⟶127 | 18 | 224⟶98 | 14 | 3.73 | 2.25 |

| 23 | Omethoate | 213 | (M+H)+ | 20 | 214⟶125 | 18 | 214⟶183 | 15 | 3.1 | 4.35 |

| 24 | Oxadiazon | 344 | (M+H)+ | 30 | 345⟶220 | 13 | 345⟶177 | 40 | 24.27 | 1.49 |

| 25 | Oxydemeton-methyl | 246 | (M+H)+ | 20 | 247 ⟶109 | 25 | 247 ⟶169 | 14 | 3.26 | 1.28 |

| 26 | Phosphamidon | 299 | (M+H)+ | 26 | 300⟶127 | 20 | 300⟶174 | 10 | 12.47 | 2.71 |

| 27 | Phoxim | 298 | (M+H)+ | 16 | 299⟶129 | 13 | 299⟶153 | 11 | 21.46 | 5.91 |

| 28 | Primiphos-methyl | 305 | (M+H)+ | 30 | 306⟶108 | 28 | 306⟶164 | 17 | 22.44 | 4.76 |

| 29 | Propiconazole | 341 | (M+H)+ | 40 | 342⟶159 | 30 | 342⟶69 | 16 | 21.26 | 1.04 |

| 30 | Propoxur | 209 | (M+H)+ | 20 | 210⟶111 | 14 | 210⟶168 | 8 | 13.93 | 3.23 |

| 31 | Pyrazophos | 373 | (M+H)+ | 36 | 374⟶222 | 30 | 374⟶194 | 21 | 22.13 | 1.3 |

| 32 | Spinosyn A | 732 | (M+H)+ | 53 | 733⟶142 | 30 | 733⟶98 | 56 | 26.65 | 3.72 |

| 33 | Spinosyn D | 746 | (M+H)+ | 50 | 747⟶142 | 31 | 747⟶98 | 51 | 27.44 | 4.36 |

| 34 | TCMTB | 238 | (M+H)+ | 21 | 239⟶180 | 10 | 239⟶136 | 40 | 18.1 | 3.6 |

| 35 | Thiobencarb | 257 | (M+H)+ | 18 | 258⟶125 | 20 | 258⟶100 | 13 | 22.57 | 7.66 |

| 36 | Thiophanate-methyl | 342 | (M+H)+ | 24 | 343⟶151 | 22 | 343⟶311 | 12 | 13.51 | 6.06 |

| 37 | Triadimenol | 295 | (M+H)+ | 20 | 296⟶70 | 8 | 296⟶99 | 15 | 19.66 | 7.43 |

| 38 | Tri-allate | 303 | (M+H)+ | 32 | 304⟶86 | 20 | 304⟶143 | 24 | 25.34 | 1.08 |

| 39 | Triazophos | 313 | (M+H)+ | 31 | 314⟶162 | 18 | 314⟶119 | 32 | 18.85 | 1.8 |

| 40 | Tricyclazole | 189 | (M+H)+ | 38 | 190⟶136 | 27 | 190⟶163 | 22 | 10.4 | 1.41 |

| 41 | Triflumizole | 345 | (M+H)+ | 10 | 346⟶278 | 8 | 346⟶73 | 25 | 23.17 | 2.36 |

| 42 | Triphenylphosphate* | 326 | (M+H)+ | 20 | 327⟶77 | 45 | 327⟶152 | 45 | 20.81 | 1.94 |

Internal standard.

Sample preparation for processing

Before cooking process, 5 mL of mixed pesticides (1000 μg/mL) standard stock solution were dissolved in 2.5 L tap water (final concentration 2 μg/mL). Two-hundred and fifty grams of rice sample was submerged in the mentioned solutions containing the 41 pesticides followed by air-drying at room temperature in a hood for 24 h. A 50 g portion of the samples was ground with 50 g dry ice and analyzed as control sample and the rest was used for evaluation of different processing factors. For each process (including washing and cooking) 50 g rice was used.

Cooking rice in Iranian traditional method (Kateh)

Washing

A 50 g portion of the rice samples was completely washed twice with tap water and soaked in water. After 20 min, the samples were ground with dry ice and then analyzed.

Cooking

For each sample, a mixture of 50 g of the rice sample, 50 mL of water, 2 g NaCl and 4 g edible oil were placed in a container. The mixture was boiled on a stove until the water was evaporated. Then, the lid of the container was completely closed and the flame of the stove minimized and rice sample steamed for 20 min. Then, the cooked rice sample were completely crushed and analyzed.

Extraction

Extraction was performed by the original QuEChERS method (16). Five g of homogenized rice sample was accurately weighed into a 50 mL centrifuge tube. Appropriate concentrations of the mixed working standard solution (for spiking) and internal standard (TTP) were added to the tube and 10 mL of acetonitrile (MeCN) was added. The mixture was mixed using a vortex for 2.0 min, followed by addition of a mixture of 4 g anhydrous MgSO4 and 1.5 g sodium acetate and mixed using a vortex for 2.0 min again. The mixture was centrifuged for 5 min at 5433×g, and 5 mL of the supernatants then transferred into an appropriate tube placed in a nitrogen evaporator and evaporated at 40 °C until dryness. The residue was reconstituted in 0.5 mL MeCN. The mixture was mixed using a vortex for 2.0 min followed by sonication for 4.0 min and the solution was transferred to a tube containing 60 mg anhydrous MgSO4 and 20 mg primary secondary amine (PSA). The mixture was mixed using a vortex vigorously for 2 min and centrifuged for 5 min at 5433×g. Finally, a 0.4 mL aliquot of the cleaned extract was transferred into a screw cap vial and 100 μL of the solution injected into LC-MS/MS.

Liquid chromatography

The separation of the different pesticides from the samples was carried out using an Alliance separations module 2695 (Waters, Milford, MA, USA), which consist of a quaternary solvent delivery system, degasser, autosampler, column heater, and diode array detector coupled with a Quattro Micro Triple Quadrupole LC/MS (Waters, Micromass, Manchester, UK).

Chromatographic separation was performed using an Agilent ZORBAX Eclipse XDB-C18 (Narrow-Bore 2.1 × 150 mm, 3.5-micron) analytical column at a flow rate of 0.2 mL/min and an injection volume of 100 μL. The mobile phase was 5 mM ammonium formate in methanol (solvent A) and 5 mM ammonium formate in water (solvent B) in a gradient mode and a total analysis time of 30 min. The elution program was as follows: at the start 30% solvent A and 70% solvent B; the percentage of solvent A was linearly increased to 100% in 20 min, then constant for 5 min and ramped to original composition in 5 min. The temperature of the column heater was maintained at 40 °C.

Mass spectrometry

The MS/MS system consisting of a triple quadrupole mass spectrometer Quattro Micro (Waters-Micromass, UK) was equipped with an electrospray source (Z-spray) and operated in positive ionization mode. MassLynx software, version 4.0, was used for instrument control and data acquisition. Analysis was performed in positive ion mode. The ESI source values were as follow: capillary voltage: 4.12 kV; extractor: 2 V; RF lens: 0.1 V; source temperature: 120 °C; desolvation temperature: 300 °C; and desolvation gas and cone gas (nitrogen 99.99% purity) flow rates: 500 and 50 L/h, respectively. The analyzer settings were as follow: resolution: 14.6 (unit resolution) for LM1 and LM2 resolution and 14 for HM1 and HM2 resolution; ion energy 1 and 2, 0.3 and 3.0, respectively; entrance and exit energies: 55 and 75 (V); multiplier: 700 (V); and collision gas (argon, 99.995%) pressure: 5.35 × 10-3 mbar.

MS/MS conditions for all pesticides were conducted in the positive electrospray ionization mode using multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) with two mass transitions. The optimization of the precursor ion, product ions, cone voltage and collision energy was performed via direct injection of the individual pesticide standard solution (1 μg/mL) into the mass spectrometer using a syringe pump at flow rate 10 μL/min. The product ion with the strongest intensity was used for quantitation, while the other with the lowest intensity was employed for confirmation

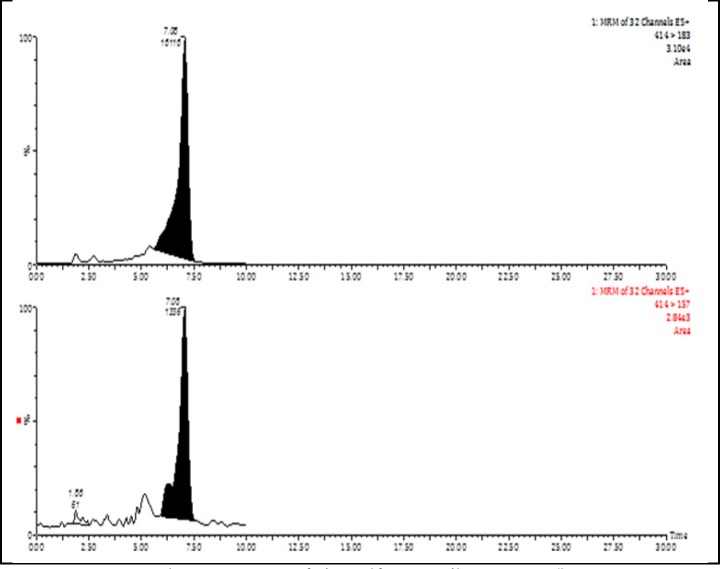

(Figure 1). The optimized parameters are presented in Table 1.

Figure 1.

MRM Chromatograms of cinosulfuron (spike: 0.05 mg/kg

Validation studies

The validation study was performed based on the European SANCO guidelines (17). Linearity was studied using matrix-matched calibration curve by analyzing in triplicate six concentration levels, between 0.02 and 1.0 mg/kg. For determination of mean recoveries and precision five spiked blank rice samples at concentration levels of 0.025, 0.250, and 1.000 mg/kg were prepared and then treated according to the procedure described in sample preparation. The limit of quantification (LOQ) was established as the lowest validated spike level meeting the method performance acceptability criteria (mean recoveries in the range 70-120%, with an RSDr ≤ 20%), and the limits of detection (LOD) estimated by a signal-noise ratio. The concentration of pesticides were determined by interpolation of the relative peak areas for each pesticide to internal standard peak area in the sample on the matrix-matched calibration curve. In order to compensate for losses during sample processing and instrumental analysis, internal standard (TPP) was used. Quality control samples were prepared using cooked rice at three concentration levels (0.025, 0.250, and 1.000 mg/kg) and validation parameters were calculated for them. All figures of merits were within the acceptable limits.

Statistical analysis

Pesticide residue reduction during processing was evaluated by calculating the processing factor (PF) according to the equation PF = Mean Cafter/Mean Cbefore, where Cafter and Cbefore are the pesticide residue levels after and before processing (18). Final Data of residue levels were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD), which were statistically evaluated by t-test analysis with Excel software. When residues were below limit of quantification (LOQ) after processing, the PF value was set as zero.

Results and Discussion

Method validation

Calibration curves were obtained by analyzing in triplicate six concentration levels, between 0.01 and 1.25 mg/kg. The range of coefficient of determinations (r2) was between 0.993 and 0.999. As shown in Table 2, mean recoveries ranged from 71-119% with satisfactory precision (RSDr < 20%). The limits of quantification (LOQ) and the limits of detection (LOD) ranged between 0.010-0.025 mg/kg and 0.003-0.008 mg/kg, respectively.

Table 2.

Mean recoveries (%) and relative standard deviations, RSDr (%), LOQs and LODs (mg/kg) obtained for 41 compounds in rice samples, spiked at 0.025, 0.250 and 1.000 mg/kg levels (n = 5)

| NO. | Compound |

0.025 mg/kg

|

0.250 mg/kg

|

1.000 mg/kg

|

LOQ

(mg/kg) |

LOD

(mg/kg) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | RSDr | Mean | RSDr | Mean | RSDr | ||||

| 1 | Azinphos-ethyl | 90 | 4 | 85 | 8 | 81 | 2 | 0.015 | 0.005 |

| 2 | Bromacil | 104 | 5 | 79 | 5 | 81 | 8 | 0.016 | 0.005 |

| 3 | Carbaryl | 96 | 5 | 84 | 8 | 81 | 3 | 0.009 | 0.003 |

| 4 | Carbofuran | 81 | 8 | 82 | 7 | 84 | 9 | 0.012 | 0.004 |

| 5 | Cartap | 92 | 18 | 101 | 16 | 99 | 9 | 0.015 | 0.005 |

| 6 | Chlorbromuron | 88 | 15 | 84 | 7 | 95 | 6 | 0.016 | 0.005 |

| 7 | Chlorfenvinphos | 83 | 2 | 96 | 11 | 94 | 9 | 0.018 | 0.006 |

| 8 | Chlorpyrifos | 111 | 2 | 81 | 7 | 82 | 10 | 0.019 | 0.006 |

| 9 | Cinosulfuron | 86 | 7 | 91 | 18 | 91 | 7 | 0.013 | 0.004 |

| 10 | Coumaphos | 98 | 10 | 105 | 11 | 87 | 5 | 0.019 | 0.006 |

| 11 | Dialifos | 116 | 3 | 103 | 9 | 87 | 9 | 0.014 | 0.005 |

| 12 | Diazinon | 109 | 1 | 98 | 4 | 101 | 11 | 0.016 | 0.005 |

| 13 | Dicrotophos | 94 | 13 | 92 | 11 | 98 | 8 | 0.013 | 0.004 |

| 14 | Edifenphos | 72 | 3 | 95 | 10 | 89 | 8 | 0.014 | 0.005 |

| 15 | Etrimfos | 103 | 3 | 92 | 8 | 96 | 7 | 0.016 | 0.005 |

| 16 | Fluometuron | 77 | 3 | 94 | 10 | 97 | 6 | 0.012 | 0.004 |

| 17 | Fuberidazole | 109 | 6 | 85 | 12 | 79 | 9 | 0.017 | 0.006 |

| 18 | Iprobenfos | 92 | 5 | 95 | 10 | 96 | 10 | 0.012 | 0.004 |

| 19 | Malathion | 90 | 4 | 90 | 16 | 94 | 9 | 0.013 | 0.004 |

| 20 | Methabenzthiazuron | 99 | 8 | 81 | 6 | 77 | 6 | 0.014 | 0.005 |

| 21 | Methidathion | 110 | 5 | 98 | 10 | 93 | 7 | 0.019 | 0.006 |

| 22 | Monocrotophos | 79 | 16 | 101 | 5 | 103 | 6 | 0.014 | 0.005 |

| 23 | Omethoate | 100 | 14 | 93 | 12 | 98 | 10 | 0.014 | 0.005 |

| 24 | Oxadiazon | 100 | 3 | 100 | 6 | 94 | 10 | 0.014 | 0.005 |

| 25 | Oxydemeton-methyl | 88 | 18 | 110 | 7 | 115 | 5 | 0.014 | 0.005 |

| 26 | Phosphamidon | 103 | 6 | 77 | 8 | 87 | 10 | 0.015 | 0.005 |

| 27 | Phoxim | 78 | 12 | 102 | 14 | 100 | 6 | 0.014 | 0.005 |

| 28 | Primiphos-methyl | 117 | 3 | 96 | 3 | 101 | 8 | 0.020 | 0.007 |

| 29 | Propiconazole | 107 | 3 | 87 | 6 | 89 | 12 | 0.012 | 0.004 |

| 30 | Propoxur | 75 | 7 | 86 | 18 | 83 | 12 | 0.017 | 0.006 |

| 31 | Pyrazophos | 108 | 2 | 92 | 9 | 90 | 3 | 0.010 | 0.003 |

| 32 | Spinosyn A | 102 | 9 | 94 | 17 | 100 | 18 | 0.014 | 0.005 |

| 33 | Spinosyn D | 84 | 13 | 92 | 12 | 95 | 7 | 0.016 | 0.005 |

| 34 | TCMTB | 104 | 4 | 81 | 13 | 84 | 13 | 0.014 | 0.005 |

| 35 | Thiobencarb | 104 | 4 | 100 | 10 | 95 | 8 | 0.015 | 0.005 |

| 36 | Thiophanate-methyl | 81 | 6 | 110 | 12 | 92 | 14 | 0.016 | 0.005 |

| 37 | Triadimenol | 78 | 1 | 76 | 8 | 94 | 7 | 0.012 | 0.004 |

| 38 | Triallate | 75 | 5 | 80 | 14 | 78 | 5 | 0.013 | 0.004 |

| 39 | Triazophos | 98 | 9 | 81 | 15 | 81 | 9 | 0.011 | 0.004 |

| 40 | Tricyclazole | 89 | 4 | 82 | 15 | 79 | 10 | 0.016 | 0.005 |

| 41 | Triflumizole | 79 | 12 | 84 | 13 | 95 | 12 | 0.010 | 0.003 |

Unprocessed rice samples

For calculating the amount of pesticide reduction during the washing and cooking processes, it is necessary to determine the concentration of pesticides in unprocessed rice samples. All mean concentrations (three replicate) of the studied compounds in control raw samples and after washing and cooking are shown in Table 3. The mean concentration of the studied pesticides was in the range of 0.767-1.110 mg/kg. The obtained results are in accordance with OECD guideline (>0.1 m/kg), so that various processing factors can be determined (18).

Table 3.

Mean concentrations (± SD, n = 3), mean values of processing factors (PF) and reductions (%) of the pesticides in unprocessed rice samples, after washing and cooking

| No. | Compounds | Unprocessed samples | Washing | Cooking | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concentration (mg/kg) (mean ± SD) |

Concentration (mg/kg) (mean ± SD) |

PF | Reduction (% ) |

Concentration (mg/kg) (mean ± SD) |

PF | Reduction (% ) |

||

| 1 | Azinphos-ethyl | 0.880 ( ± 0.071 ) | 0.755 ( ± 0.044 )* | 0.86 | 14.2 | 0.096 ( ± 0.034 ) | 0.11 | 89.1 |

| 2 | Bromacil | 0.961 ( ± 0.029 ) | 0.649 ( ± 0.094 ) | 0.68 | 32.5 | 0.179 ( ± 0.016 ) | 0.19 | 81.4 |

| 3 | Carbaryl | 0.880 ( ± 0.031 ) | 0.668 ( ± 0.069 ) | 0.76 | 24.1 | 0.195 ( ± 0.018) | 0.22 | 77.9 |

| 4 | Carbofuran | 0.905 ( ± 0.086 ) | 0.878 ( ± 0.058 )* | 0.97 | 3.0 | 0.505 ( ± 0.081 ) | 0.56 | 44.2 |

| 5 | Cartap | 0.842 ( ± 0.034 ) | 0.540 ( ± 0.016 ) | 0.64 | 35.8 | 0.020 ( ± 0.064 ) | 0.02 | 97.6 |

| 6 | Chlorbromuron | 0.982 ( ± 0.017 ) | 0.603 ( ± 0.076 ) | 0.61 | 38.6 | 0.498 ( ± 0.083 ) | 0.51 | 49.2 |

| 7 | Chlorfenvinphos | 0.983 ( ± 0.047 ) | 0.637 ( ± 0.088 ) | 0.65 | 35.2 | 0.286 ( ± 0.048 ) | 0.29 | 71.0 |

| 8 | Chlorpyrifos | 0.855 ( ± 0.078 ) | 0.409 ( ± 0.038 ) | 0.48 | 52.2 | 0.163 ( ± 0.018 ) | 0.19 | 80.9 |

| 9 | Cinosulfuron | 0.904 ( ± 0.088 ) | 0.871 ( ± 0.061 )* | 0.96 | 3.6 | 0.669 ( ± 0.031 ) | 0.74 | 26.0 |

| 10 | Coumaphos | 0.897 ( ± 0.030 ) | 0.837 ( ± 0.108 )* | 0.93 | 6.7 | 0.711 ( ± 0.074 ) | 0.79 | 20.7 |

| 11 | Dialifos | 0.909 ( ± 0.049 ) | 0.551 ( ± 0.071 ) | 0.61 | 39.4 | 0.385 ( ± 0.039 ) | 0.42 | 57.6 |

| 12 | Diazinon | 0.982 ( ± 0.0.25 ) | 0.492 ( ± 0.060 ) | 0.50 | 49.9 | 0.557 ( ± 0.069 ) | 0.57 | 43.3 |

| 13 | Dicrotophos | 0.956 ( ± 0.062 ) | 0.242 ( ± 0.083 ) | 0.25 | 74.7 | 0.349 ( ± 0.038 ) | 0.37 | 63.5 |

| 14 | Edifenphos | 0.921 ( ± 0.078 ) | 0.648 ( ± 0.073 ) | 0.70 | 29.7 | 0.730 ( ± 0.045 ) | 0.79 | 20.7 |

| 15 | Etrimfos | 0.996 ( ± 0.017 ) | 0.957 ( ± 0.023 )* | 0.96 | 3.9 | 0.499 ( ± 0.093 ) | 0.50 | 49.9 |

| 16 | Fluometuron | 0.903 ( ± 0.109 ) | 0.837 ( ± 0.050 )* | 0.93 | 7.3 | 0.205 ( ± 0.084 ) | 0.23 | 77.3 |

| 17 | Fuberidazole | 0.890 ( ± 0.107 ) | 0.194 ( ± 0.075 ) | 0.22 | 78.2 | 0.119 ( ± 0.067 ) | 0.13 | 86.7 |

| 18 | Iprobenfos | 0.806 ( ± 0.042 ) | 0.476 ( ± 0.047 ) | 0.59 | 41.0 | 0.408 ( ± 0.091 ) | 0.51 | 49.3 |

| 19 | Malathion | 0.982 ( ± 0.031 ) | 0.864 ( ± 0.010 ) | 0.88 | 12.0 | 0.260 ( ± 0.004 ) | 0.26 | 73.6 |

| 20 | Methabenzthiazuron | 0.926 ( ± 0.082 ) | 0.468 ( ± 0.086 ) | 0.51 | 49.5 | 0.331 ( ± 0.087 ) | 0.36 | 64.3 |

| 21 | Methidathion | 0.958 ( ± 0.065 ) | 0.641 ( ± 0.067 ) | 0.67 | 33.1 | 0.242 ( ± 0.047 ) | 0.25 | 74.7 |

| 22 | Monocrotophos | 0.767 ( ± 0.024 ) | 0.562 ( ± 0.091 ) | 0.73 | 26.7 | 0.350 ( ± 0.027 ) | 0.46 | 54.4 |

| 23 | Omethoate | 0.783 ( ± 0.098 ) | 0.284 ( ± 0.048 ) | 0.36 | 63.7 | 0.339 ( ± 0.029 ) | 0.43 | 56.7 |

| 24 | Oxadiazon | 0.979 ( ± 0.089 ) | 0.117 ( ± 0.115 ) | 0.12 | 88.1 | 0.216 ( ± 0.060 ) | 0.22 | 77.9 |

| 25 | Oxydemeton-methyl | 0.793 ( ± 0.035 ) | 0.183 ( ± 0.061 ) | 0.23 | 76.9 | <LOQ | 0.00 | 99.0 |

| 26 | Phosphamidon | 0.911 ( ± 0.035 ) | 0.677 ( ± 0.082 ) | 0.74 | 25.7 | 0.474 ( ± 0.053 ) | 0.52 | 48.0 |

| 27 | Phoxim | 1.012 ( ± 0.074 ) | 0.615 ( ± 0.030 ) | 0.61 | 39.2 | 0.722 ( ± 0.034 ) | 0.71 | 28.6 |

| 28 | Primiphos-methyl | 1.019 ( ± 0.109 ) | 0.793 ( ± 0.097 )* | 0.78 | 22.1 | 0.139 ( ± 0.056 ) | 0.14 | 86.4 |

| 29 | Propiconazole | 0.935 ( ± 0.092 ) | 0.064 ( ± 0.041 ) | 0.07 | 87.1 | 0.432 ( ± 0.096 ) | 0.46 | 53.8 |

| 30 | Propoxur | 0.885 ( ± 0.021 ) | 0.586 ( ± 0.092 ) | 0.66 | 33.7 | 0.202 ( ± 0.009 ) | 0.23 | 77.2 |

| 31 | Pyrazophos | 0.910 ( ± 0.014 ) | 0.416 ( ± 0.007 ) | 0.46 | 54.3 | 0.502 ( ± 0.036 ) | 0.55 | 44.8 |

| 32 | Spinosyn A | 1.110 ( ± 0.057 ) | 0.586 ( ± 0.043 ) | 0.53 | 47.2 | 0.344 ( ± 0.070 ) | 0.31 | 69.0 |

| 33 | Spinosyn D | 0.975 ( ± 0.064 ) | 0.413 ( ± 0.103 ) | 0.42 | 57.6 | 0.226 ( ± 0.087 ) | 0.23 | 76.9 |

| 34 | TCMTB | 0.905 ( ± 0.007 ) | 0.213 ( ± 0.021 ) | 0.24 | 76.5 | 0.067 ( ± 0.041 ) | 0.07 | 92.6 |

| 35 | Thiobencarb | 0.990 ( ± 0.042 ) | 0.300 ( ± 0.002 ) | 0.30 | 69.7 | 0.505 ( ± 0.036 ) | 0.51 | 49.0 |

| 36 | Thiophanate-methyl | 1.000 ( ± 0.028 ) | 0.241 ( ± 0.024 ) | 0.24 | 75.9 | 0.299 ( ± 0.057) | 0.30 | 70.1 |

| 37 | Triadimenol | 0.912 ( ± 0.054 ) | 0.462 ( ± 0.036 ) | 0.51 | 49.3 | 0.258 ( ± 0.061 ) | 0.28 | 71.7 |

| 38 | Triallate | 0.800 ( ± 0.028 ) | 0.491 ( ± 0.096 ) | 0.61 | 38.6 | 0.279 ( ± 0.013 ) | 0.35 | 65.1 |

| 39 | Triazophos | 0.850 ( ± 0.014 ) | 0.223 ( ± 0.005 ) | 0.26 | 73.8 | 0.359 ( ± 0.090 ) | 0.42 | 57.8 |

| 40 | Tricyclazole | 0.835 ( ± 0.021 ) | 0.229 ( ± 0.044 ) | 0.27 | 60.6 | 0.409 ( ± 0.041 ) | 0.49 | 51.1 |

| 41 | Triflumizole | 1.001 ( ± 0.028 ) | 0.357 ( ± 0.040 ) | 0.36 | 64.3 | 0.484 ( ± 0.093 ) | 0.48 | 51.6 |

Values are not significantly different (p > 0.05).

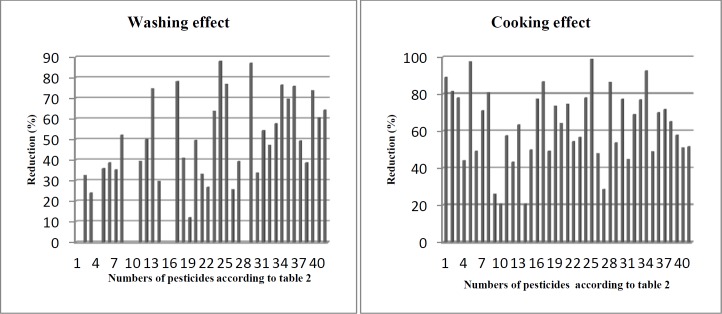

Effects of washing

Washing is the most common form and generally the first step in household food processing. This study showed that washing removed different portions of pesticide residues. As shown in Table 3 and Figure 2, washing process removed the residues of 34 pesticides in the range between 12.0-88%, whereas azinphos-ethyl (organophosphate), carbofuran (carbamate), cinosulfuron (sulfonylurea), coumaphos (organothiophosphate), etrimfos (organophosphate), fluometuron (phenylurea), and primiphos-methyl (phosphorothioate) did not significantly get removed by washing. The most reduction occurred in oxadiazon (88.1%) and propiconazole (87.1%) that chemically belong to oxidiazole and triazole groups, respectively. On the other hand, the least removal occurred in the levels of malathion (12%), carbaryl (24.1%), and phosphamidon (25.7%). Our findings indicated that there was no correlation between chemical structure and the levels of residue removed by washing. For example in organophosphate group, the residues of etrimfos was not significantly decreased, while phoxim, omethoate, and oxydemeton-methyl were decreased 39.2% and 63.7%, and 76.9%, respectively. Therefore, we suggest that the loosely attached pesticides at surface of rice matrix were easily removed by washing. Our findings are consistent with previous studies. Angel Yang et al. (19), Chavarri et al. (20), and Kaushik et al. (21) suggested that the loosely attached residues were simply washed and removed from the surface of polluted food samples. We also found that there is no correlation between water solubility and residue removed by washing. For example, the residues of oxadiazon and spinosyn D with water solubility 0.70 and 0.33 g/mL were decreased 88.1% and 57.6%, respectively, while the reduction of phosphamidon and monocrotophos with water solubility 1.00E+06 and 8.18+05 g/mL was 25.7% and 26.7%, respectively (Tables 3 and 4). Previously, Cabras et al. (22, 23) and Walter et al. (24) indicated that water solubility is not a principal agent for removing pesticide residues by washing. Kaddus Miah et al. demonstrated that rice has high capacity for absorbing water during soaking (25). In this study, rice samples were soaked in contaminated water with different pesticides. Therefore, we propose that some very soluble pesticides such as phosphamidon and monocrotophos deeply penetrate to rice seeds and washing process cannot completely remove the residues.

Figure 2.

Effects of washing and cooking on pesticides residues in rice

Table 4.

Physico-chemical properties of the pesticides studied in this investigation (according to the references 2-6).

| No. | Compound | Molecular formula | Chemical group | Pesticide type | Melting Point (°C) | log P (octanol-water) | Water solubility (mg L-1) at 25 °C | Vapour Pressure (Pa) at 25 °C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Azinphos-ethylb | C12H16N3O3PS2 | Organophosphate | Insecticide, Acaricide | 53 | 3.4 | 10.5 | 1.80E-08 |

| 2 | Bromacilb | C9H13BrN2O2 | Uracil | Herbicide | 158 | 2.11 | 815 | 2.30E-09 |

| 3 | Carbaryla | C12H11NO2 | Carbamate | Insecticide, Plant growth regulator | 145 | 2.36 | 110 | 1.02E-08 |

| 4 | Carbofuranb | C12H15NO3 | Carbamate | Insecticide, Nematicide, Acaricide, Metabolite | 151 | 2.32 | 320 | 3.64E-08 |

| 5 | Cartapa | C7H15N3O2S2 | Unclassified | Insecticide | 131 | -0.95 | 2.0 E 05 | 7.50E-13 |

| 6 | Chlorbromuronb | C9H10BrClN2O2 | Urea | Herbicide | 96 | 3.09 | 35 | 2.98E-09 |

| 7 | Chlorfenvinphosb | C12H14Cl3O4P | Organophosphate | Insecticide, Acaricide, Veterinary treatment | -20 | 3.81 | 124 | 5.63E-08 |

| 8 | Chlorpyrifosa | C9H11Cl3NO3PS | Organophosphate | Insecticide | 42 | 4.96 | 1.12 | 1.52E-07 |

| 9 | Cinosulfurona | C15H19N5O7S | Sulfonylurea | Herbicide | 130 | 2.04 | 120 | 5.19E-15 |

| 10 | Coumaphosb | C14H16ClO5PS | Organothiophosphates | Insecticide, Miticide | 93 | 4.13 | 1.5 | 7.28E-10 |

| 11 | Dialifosb | C14H17ClNO4PS2 | Organophosphate | Insecticide, Acaricide | 68 | 4.69 | 0.18 | 4.65E-10 |

| 12 | Diazinona | C12H21N2O3PS | Organophosphate | Insecticide, Acaricide, Repellent, Veterinary treatment | < 25 | 3.81 | 40 | 6.76E-07 |

| 13 | Dicrotophosb | C8H16NO5P | Organophosphate | Insecticide | < 25 | -0.49 | 1.00E+06 | 1.20E-06 |

| 14 | Edifenphosa | C14H15O2PS2 | Organophosphate | Fungicide | < 25 | 3.48 | 56 | 2.03E-09 |

| 15 | Etrimfosb | C10H17N2OPS | Organophosphate | Insecticide | -3.35 | 2.94 | 40 | 6.00E-07 |

| 16 | Fluometuronb | C10H11F3N2O | Phenylurea | Herbicide | 164 | 2.42 | 110 | 7.04E-09 |

| 17 | Fuberidazoleb | C11H8N2O | Benzimidazole | Fungicide | 292 | 2.67 | 71 | 5.06E-11 |

| 18 | Iprobenfosb | C13H21O3PS | Organophosphate | Fungicide | < 25 | 3.34 | 400 | 3.04E-07 |

| 19 | Malathiona | C10H19O6PS2 | Organophosphate | Insecticide, Acaricide, Veterinary treatment | 2.8 | 2.36 | 143 | 2.54E-08 |

| 20 | Methabenzthiazuronb | C10H11N3OS | Urea | Herbicide | 120 | 2.64 | 59 | 8.48E-10 |

| 21 | Methidathionb | C6H11N2O4PS3 | Organophosphate | Insecticide, Acaricide | 39 | 2.2 | 187 | 2.53E-08 |

| 22 | Monocrotophosb | C7H14NO5P | Organophosphate | Insecticide, Acaricide | 55 | -0.2 | 8.18+05 | 1.64E-08 |

| 23 | Omethoateb | C5H12NO4PS | Organophosphate | Insecticide, Acaricide, Metabolite | -28 | -0.74 | 1.00E+06 | 1.86E-07 |

| 24 | Oxadiazona | C15H18Cl2N2O3 | Oxidiazole | Herbicide | 90 | 4.8 | 0.7 | 8.40E-10 |

| 25 | Oxydemeton-methyla | C6H15O4PS2 | Organophosphate | Insecticide | -20 | -0.74 | 1.00E+06 | 2.14E-07 |

| 26 | Phosphamidonb | C10H19ClNO5P | Organophosphate | Insecticide, Acaricide | -45 | 0.79 | 1.00E+06 | 1.24E-07 |

| 27 | Phoximb | C12H15N2O3PS | Organophosphate | Insecticide, Disinfectant | 6.1 | 4.39 | 4.1 | 1.19E-07 |

| 28 | Pirimiphos-methyla | C11H20N3O3PS | Organophosphate | Insecticide, Acaricide | 15 | 4.2 | 8.6 | 1.13E-07 |

| 29 | Propiconazolea | C15H17Cl2N3O2 | Triazole | Fungicide | < 25 | 3.72 | 110 | 7.50E-09 |

| 30 | Propoxurb | C11H15NO3 | Carbamate | Insecticide, Acaricide, Veterinary treatment | 87 | 1.52 | 1860 | 7.26E-08 |

| 31 | Pyrazophosb | C14H20N3O5PS | Phosphorothiolate | Fungicide | 51 | 3.8 | 4.2 | 7.35E-10 |

| 32 | Spinosyn Aa | C41H65NO10 | Micro-organism derived | Insecticide, Veterinary treatment | 84-99.5 | 4 | 235 | 3.00E-05 |

| 33 | Spinosyn Da | C42H67NO10 | Micro-organism derived | Insecticide, Veterinarytreatment | 161.5-170 | 4.5 | 0.33 | 2.00E-05 |

| 34 | TCMTBb | C9H6N2S3 | Mercaptobenzothiazole | Fungicide, Microbiocide, Wood preservative | Liquid | 3.3 | 125 | 2.34E-09 |

| 35 | Thiobencarba | C12H16ClNOS | Thiocarbamate | Herbicide | 3.3 | 3.4 | 28 | 1.65E-07 |

| 36 | Thiophanate-methyla | C12H14N4O4S2 | Benzimidazole | Fungicide | 172 | 1.4 | 26.6 | 5.35E-10 |

| 37 | Triadimenola | C14H18ClN3O2 | Triazole | Fungicide | 124 | 2.9 | 120 | 2.33E-12 |

| 38 | Triallatec | C10H16Cl3NOS | Thiocarbamate | Herbicide | 29 | 4.6 | 4 | 9.00E-07 |

| 39 | Triazophosb | C12H16N3O3PS | Organophosphate | Insecticide, Acaricide, Nematicide | 3.5 | 3.34 | 39 | 2.18E-08 |

| 40 | Tricyclazolea | C9H7N3S | Triazolobenzothiazole | Fungicide | 187 | 1.7 | 1600 | 1.50E-09 |

| 41 | Triflumizolea | C15H15ClF3N3O | Imidazole | Fungicide | 63.5 | 1.4 | 1.25E+04 | 1.05E-08 |

Permitted pesticides in Iran for rice production.

Prohibited pesticides in Iran for rice production.

Effects of cooking

As shown in Table 3, the amounts of the pesticide residues decreased in range 20.7-100%. Oxydemeton-methyl (organophosphate) completely was removed (<LOQ) and the lowest removal occurred for coumaphos (organothiophosphate) and edifenphos (organophosphate). The residue reductions were not associated with the chemical group which the pesticide belong to. For example, in organophosphate group the concentration of edifenphos, diazinon, dicrotophos, and oxydemeton-methyl was decreased 20.7%, 43.3% 63.5%, and 100%, respectively. This controversial reduction was observed in other groups such as carbamates. Cooking rice in Iranian method (Kateh) consists of two principal steps; boiling and steam cooking. During boiling, the system is open and the temperature of system rises to 100 °C. During steam cooking, the lid of container is tightly closed and cooking is completed under pressure and high temperature. Under these conditions, volatilization, hydrolysis, and thermal degradation may reduce pesticide residues. Our findings are consistent with previous studies (27, 28). Briefly, our results indicated that the removal of pesticide residues in this study was associated with both physicochemical properties of pesticides and cooking conditions.

Conclusion

Pesticide residue in various commodities including rice is a major challenge in food safety. Rice is cooked in different methods all around the world and this study confirmed that Iranian home cooking processes reduced residue levels in contaminated rice. Washing and cooking removed different portions of pesticide residues in the range between 12.0-88.1% and 20.7-100%, respectively. The residue reductions were not correlated with chemical structure or water solubility of the pesticides but intensity of pesticide bindings to rice matrix, volatilization, hydrolysis, and thermal degradation determined the amounts of residues removed. In conclusion, proper home processing of rice before eating can result to reduction of intake of pesticide residues through rice consumption.

Acknowledgment

The authors gratefully acknowledge Iranian National Science Foundation (Project No. 88000212) for the financial support. We are also very grateful to Golnaz Mirzaee and Shervin Soulatti.

References

- 1.Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations. Rice and human nutrition. Rome: FAO; 2004. pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 2.International Rice Research Institute. Rice almanac. Manila: IRRI; 2013. pp. 7–10. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations. FAO Statistical Yearbook. Rome: FAO; 2013. pp. 150–65. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lucía P, Verónica C, Horacio H, Amadeo RFA. Evaluation of various QuEChERS based methods for the analysis of herbicides and other commonly used pesticides in polished rice by LC–MS/MS. Talanta . 2011;83:1613–22. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2010.11.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joanna J, Wojciech H, Carolina J, Christofer L, Sandra C, Peter Van Den H, Margaret S, Rolf Z. Adverse health effects of children’s exposure to pesticides: What do we really know and what can be done about it. ActaPaediatr. 2006;95 (Suppl):71–80. doi: 10.1080/08035320600886489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.European Council Directives. 76/895/EEC, 86/362/EEC, 86/363/EEC and 90/642/EEC. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iranian National Standards Organization (INSO) Pesticides –Maximum residue limit of pesticides - Cereals, 13120. 1st edition 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee SW, Choi JH, Cho SK, Yu HA, Abd El-Aty AM, Shim JH. Development of a new QuEChERS method based on dry ice for the determination of 168 pesticides in paprika using tandem mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A . 2011;1218:4366–77. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2011.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pareja L, Ferna´ndez-Alba AR, Cesio V, Heinzen H. Analytical methods for pesticide residues in rice. Trends Anal. Chem. 2011;30:270–91. [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Food Service Management Institute (US) Preparing pasta, rice and grains. Mississippi: Mississippi University; 2009. pp. 10–5. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lalah JO, Wandiga SO. The effect of boiling on the removal of persistent malathion residues from stored grains. J. Stored Prod. Res. 2002;38:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Castro MFPM de Oliveira JJ, Rodrigues J, Loredo ISD, Liveira JJ, Highley EA. Study on the persistence of trifluralin, chlorpyrifos , decamethrin , cypermethrin , dichlorvos in rice, beans after cooking in a commercial microwave oven. In: Credland PF, Armitage DM, Bell CH, Cogan PM., editors. Advances-In-Stored-Product-Protection. NY, USA: Proceedings of the 8th international working conference on stored product protection; 2002. pp. 517–21. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shoeibi S, Amirahmadi M, Yazdanpanah H, Pirali-Hamedani M, Pakzad SR, Kobarfard F. Effect of cooking process on the residues of three carbamate pesticides in rice. Iran. J. Pharm. Res. 2011;10:119–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aurore B, Vincent H, Ruben J, Marc H, Claude B, Thomas B, Joris VL. Effect of household and industrial processing on levels of five pesticide residues and two degradation products in spinach. FoodControl . 2012;25:397–406. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Angel Y, Jong-Hyouk P, Abd El-Aty AM, Jeong-Heui C, Jae-Ho O, Kisung K, Ki-Hoon S, Ok-Ja C, Jae-Han S, Jung-Ah D. Synergistic effect of washing and cooking on the removal of multi-classes of pesticides from various food samples. Food Control . 2012;25:99–105. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anastassiades M, Lehotay SJ, Stajnbaher D, Schenck FJ. Fast and easy multiresidue method employing acetonitrile extraction/partitioning and “dispersive solid-phase extraction” for the determination of pesticide residues in produce. J. AOAC Int. 2003;86:412–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.European Commission, Directorate General Health and Consumer Protection, Commission working document. SANCO/12495/2011. Method Validation and Quality Control Procedures for Pesticide Residues Analysis in Food and Feed . 2012. pp. 1–45. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Guideline for testing of chemicals. Magnitude of the pesticide residues in processed commodities. No. 508. Paris : OECD; 2008. pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang A, Park JH, Abd El-Aty AM, Choi JH, Jae-Ho O, Kisung K, Ki-Hoon S, Ok-Ja C, Jae-Han S, Jung-Ah D. Synergistic effect of washing and cooking on the removal of multi-classes of pesticides from various food samples. Food Control . 2012;28:99–105. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chavarri MJ, Herrera A, Arino A. The decrease in pesticides in fruits and vegetables during commercial processing. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2005;40:205–11. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaushik G, Satya S, Naik SN. Food processing a tool to pesticide residue dissipation - A review. Food Res. Int. 2009;42:26–40. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cabras P, Angioni A, Garau VL, Minelli EV, Cabitza F, Cubeddu M. Residues of some pesticides in fresh and dried apricots. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1997;45:3221–2. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cabras P, Angioni A, Garau VL, Minelli EV, Cabitza F, Cubeddu M. Pesticide residues in prune processing. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1998;46:3772–4. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Walter JK, Arsenault TL, Pylypiw HM, Mattina MJI. Reduction of pesticide residues on produce by rinsing. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000;48:4666–70. doi: 10.1021/jf0002894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaddus Miah MA, Anwarul H, Paul Douglass M, Brian C. Parboiling of rice. Part I: Effect of hot soaking time on quality of milled rice. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2002;37:527–37. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pesticide Properties Database. University of Hertfordshire; Available from: URL: http://sitem.herts.ac.uk/aeru/footprint/index2.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abou-Arab AAK. Behavior of pesticides in tomatoes during commercial and home preparation. Food Chem. 1999;4:509–14. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Balinova AM, Mladenova RI, Shtereva DD. Effects of processing on pesticide residues in peaches intended for baby food. Food Addit. Contam. 2006;23:895–901. doi: 10.1080/02652030600771715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]