Highlights

-

•

Small intestine gastrointestinal stromal tumors can infrequently present with intra-abdominal abscess, perforation, obstruction or fistula.

-

•

Tumor-small intestine fistula is a rare phenomenon and occurs as a result of GISTs’ propensity to cause mucosal ulceration.

-

•

Although liver metastases are common, in the rare case of a GIST complicated by gastrointestinal tract perforation, abscess or fistula, a pyogenic liver abscess is another important entity to consider.

-

•

Positive blood cultures with members of the S. milleri group should prompt consideration of occult abdominal infection, perforation and gastrointestinal malignancy.

Abbreviations: GIST, gastrointestinal stromal tumor; RFS, recurrence free survival; OS, overall survival; CT, computed tomography; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; CA 19-9, cancer antigen 19-9; AFP, alpha-fetoprotein; PDGFR, platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha

Keywords: GIST, Small intestine, Liver abscess, Streptococcus anginosus, Case report, Fistula

Abstract

Introduction

Small intestine gastrointestinal stromal tumors can infrequently present with intra-abdominal abscess, perforation, obstruction or fistula. Tumor-small intestine fistula is a rare phenomenon and occurs as a result of GISTs’ propensity to cause mucosal ulceration. This allows bacteria from the gut to gain access to the systemic circulation and predisposes the patient to bacteremia and pyogenic liver abscess.

Presentation of case

We present a case of a 63-year-old female whose initial symptoms included fever, nausea, vomiting and right upper quadrant pain. Radiologic studies revealed a liver lesion and an intra-abdominal mass containing oral contrast, suggesting involvement of the gastrointestinal tract. She was found to have a liver abscess, Streptococcus anginosus bacteremia and an ileal GIST that formed a fistula between the tumor and small intestine. We performed a surgical resection of the tumor and percutaneous drainage of the liver abscess. Imatinib was initiated post operatively and she experienced no recurrence, as demonstrated by a surveillance computed tomography scan at 12 months.

Conclusion

Findings of a liver lesion in association with a small intestine GIST should raise concern for both metastatic disease and a possible infectious complication such as a pyogenic liver abscess. If a member of the Streptococcus milleri group is isolated in blood cultures, a consideration for gastrointestinal malignancy is imperative. This case report reviews a rare presentation of an ileal GIST with tumor-intestinal fistula, complicated by liver abscess and Streptococcus anginosus bacteremia.

1. Introduction

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) are the most common mesenchymal tumors of the gastrointestinal tract 1,2. The predominant anatomical locations in which GISTs are diagnosed are the stomach (60%) and small intestine (20–30%) 1. Less frequently, they are found in the colon, rectum, appendix, esophagus, mesentery, omentum, or retroperitoneum 1,2. Many GISTs present with vague symptoms which can include abdominal pain, early satiety, abdominal distension, gastrointestinal bleeding and an enlarging mass 1,2. Perforation and obstruction, albeit rare, is more common with small intestine rather than gastric GISTs 3. Presentations that are even more infrequent include tumor perforation, GIST related fistulas and intra-abdominal abscesses [4], [5], [6], [7].

We report a case in which a patient presented with right upper quadrant pain, Streptococcus anginosus bacteremia, a liver lesion and an intra-abdominal complex mass. The final diagnosis was an ileal GIST with tumor-bowel fistula and a liver abscess. Small intestinal GIST-related fistulas represent a rare occurrence and have been described to form between various organs due to the tumor’s propensity to cause mucosal ulceration 4,6. This provides a path for systemic and portal translocation of gastrointestinal inhabitants. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors rarely metastasize to the lymphatic system, but rather, they favor local invasion, peritoneal dissemination and hematogenous spread to the liver 1,2. In the case of a patient with a liver lesion and a GIST complicated by gastrointestinal tract perforation, abscess or fistula, in addition to initiating work up for metastatic disease, a pyogenic liver abscess is an important entity to consider. Similar to the association between Streptococcus bovis and colorectal malignancies, when presented with a patient with Streptococcus anginosus bacteremia, a gastrointestinal malignancy should also be considered.

This case is of clinical interest because of the infrequency of gastrointestinal stromal tumor-intestine fistulas. Recognition of pyogenic liver abscess as potential sequelae of GIST facilitates appropriate and timely treatment with intravenous antibiotics and possibly percutaneous or surgical drainage. We also reinforce the need to consider gastrointestinal malignancy when S. anginosus, which is part of normal flora, is found outside of its’ expected intraluminal location in the gastrointestinal or genitourinary tract. The patient was managed in a community hospital setting. This case has been reported in line with the SCARE criteria 8.

2. Case presentation

A 63-year-old Hispanic female was brought to the emergency department by family with a two day history of right upper quadrant pain. Associated symptoms were nausea, vomiting, fevers and chills. Her past medical history included hypertension and diabetes mellitus. Her surgical history was significant for a laparoscopic cholecystectomy performed in an outside facility 9 years prior. The patient denied any family or personal history of malignancy or genetic disorders. Her family history only included diabetes in her deceased father, in whom she stated cause of death was unknown. Patient’s home medications included Omeprazole 20 mg daily, Amlodipine 5 mg daily and Sitagliptin/Metformin 50/500 mg tab twice a day. She denied any history of tobacco, alcohol and recreational drug use. She was divorced and living with her adult daughter and family. The patient was normotensive, tachycardic and had a 39 °C temperature. Physical examination demonstrated tenderness in the right upper quadrant and mild tenderness in the left lower quadrant and supra-pubic area. White blood cell count was 26 on arrival (normal 3–11). Liver function tests, CEA, CA 19-9, and AFP were within normal ranges. Blood and urine cultures were obtained and the patient was sent for a computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis. CT scan with intravenous (IV) contrast revealed a complex mass with solid and cystic components involving the posterior aspect of the right lobe of the liver, measuring 4.6 cm in greatest diameter (Fig. 1). A complex mass containing internal air-fluid levels centrally in the lower abdomen was also noted (Fig. 2). A repeat CT scan with oral contrast was obtained to evaluate involvement of the gastrointestinal tract and demonstrated thickened small bowel loops, which were contiguous with a poly-lobulated mass; the central component of this mass contained oral contrast (Fig. 3). After an extensive discussion with the patient, surgical exploration was planned.

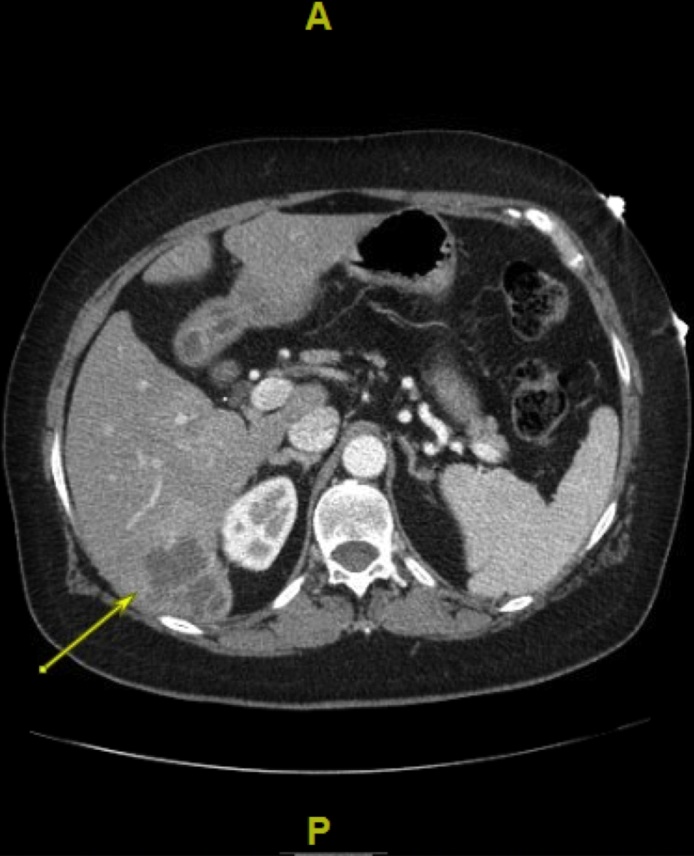

Fig. 1.

Liver lesion (arrow) identified on a CT scan of the abdomen.

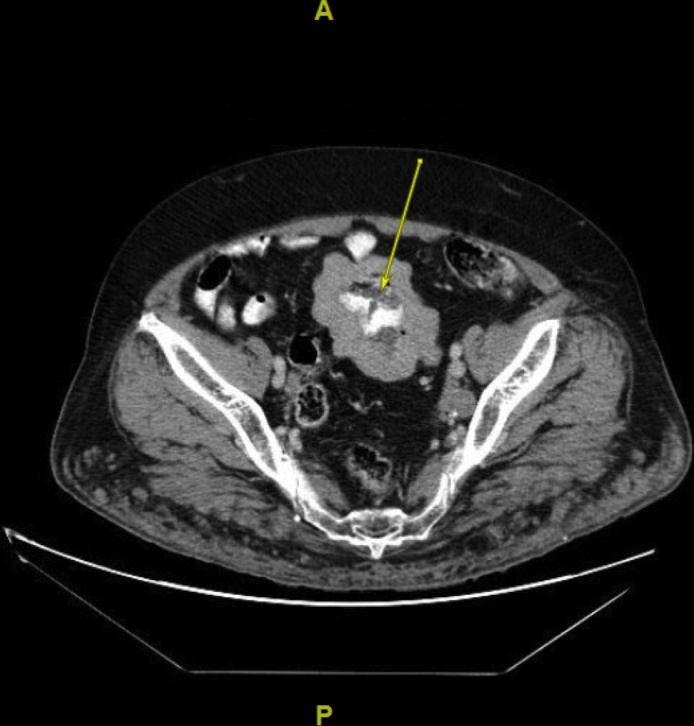

Fig 2.

CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis with an intra-abdominal mass containing internal air-fluid levels (arrow).

Fig. 3.

CT of the abdomen and pelvis demonstrating oral contrast in the center of the intra-abdominal mass (arrow).

Surgery was performed by a seasoned general surgeon, with the assistance of a second year general surgery resident. At surgery, a large pelvic mass was found and it was inseparable from two segments of ileum. Small bowel mesentery and the medial aspect of the sigmoid colon and mesocolon were adherent. Enteric spillage in the intra-abdominal cavity was not noted but there was significant inflammation in the surrounding tissue. No other suspicious lesions were identified in the abdomen. A small portion of the mesenteric mass was sent for frozen section, which revealed a spindle cell morphology. A resection of tumor with 20 cm of small bowel, 30 cm away from the ileocecal junction, was performed. The inseparable portion of the sigmoid colon was resected en block. A stapled small bowel anastomosis was then performed in a side-to-side, functional end-to-end fashion. An end colostomy was fashioned using the descending colon, in light of surrounding inflammation and an un-prepped colon. The liver lesion was not amenable to surgical biopsy due to location and inability to palpate intra-operatively. Blood cultures obtained at admission grew Streptococcus anginosus. Interventional radiology was consulted to perform an image-guided biopsy of the liver lesion, which occurred on post-operative day two. CT-guided core needle biopsies were obtained with an 18-gauge biopsy gun and 100 mL of purulent fluid was drained from the liver lesion. The radiologist inserted an 8 French pigtail catheter into the abscess cavity.

The final pathology revealed a gastrointestinal stromal tumor originating from the ileum, 9 cm in largest dimension. The tumor was communicating with the intestinal lumen via a mucosal defect, with enteric content noted through the central part of the mass. The mass was adhered to the sigmoid colon, with no violation of colonic serosa. Mitotic count was less than 5/50 high-power fields, and there was no necrosis present. The margins were free of microscopic disease and the mesenteric lymph nodes were negative for malignancy. Subsequent staining revealed CD117 (c-KIT) positive and CD34, α-smooth muscle actin and S-100-negative tissue. The final diagnosis was intermediate-risk GIST. The pathology from the liver lesion was reported as hepatic parenchyma with extensive necrosis and inflammatory cells, suggestive of abscess. Fluid cultures from the liver were positive for Streptococcus anginosus.

The patient had an unremarkable post-operative course. Three days after insertion of the drainage catheter into the liver abscess and after minimal drainage for >48 h, a follow up CT scan of the abdomen was performed. A significantly smaller hypo-attenuating lesion in the liver was noted and the catheter was removed under CT guidance. On post-operative day six, with appropriate bowel function, tolerance of a regular diet, resolution of fevers for over 72 h and normalization of the white blood cell count, she was discharged home. The patient received Ceftriaxone 2 g daily IV and Metronidazole 500 mg every eight hours orally while she remained inpatient. She was discharged on Ceftriaxone 2 g IV daily for four additional weeks. Post-operative instructions included a referral to a medical oncologist to initiate a surveillance schedule and determine necessity of adjuvant therapy, as well as a follow up surgical evaluation in ten days. The patient was started on Imatinib mesylate, 400 mg daily. She was compliant with post-operative instructions and tolerated adjuvant Imatinib with no adverse reactions or side effects. We performed a colostomy reversal 4 months after the initial operation. Pre-operative CT scan did not reveal recurrent disease and the liver abscess had resolved. The submitted specimens were microscopically free of disease and there were no suspicious lesions in the abdominal cavity. Surveillance CT scan at 12 months showed no tumor recurrence.

3. Discussion

GISTs are the most common mesenchymal tumors of the gastrointestinal tract, thought to arise from a common precursor cell of the interstitial cells of Cajal 1,2. Approximately 85% of these neoplasms result from activating mutations in one of the receptor protein tyrosine kinases, KIT (CD117) or PDGFRA 1. Wild-type tumors, with no detectable KIT or PDGFRA mutations, account for approximately 10% of all GISTs 1. GISTs are categorized as low, intermediate, or high risk for recurrence based on size, mitotic index, anatomic location and presence of rupture 1,2. It is critical to establish recurrence risk, to identify patients who benefit from adjuvant treatment. The two most widely accepted risk classification systems are the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) criteria and the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology (AFIP) criteria [9], [10], [11].

Management of GISTs is focused on the goal of complete gross resection with negative microscopic margins and an intact pseudo-capsule 10. Lymphadenectomy is not routinely performed due to infrequency of lymph node metastasis 10. Imatinib mesylate is a selective inhibitor of a family of tyrosine kinase enzymes, including KIT and PDGFRA, and is the standard therapy for inoperable, metastatic, or recurrent GISTs 9,10. It has been used with success in the neo-adjuvant and adjuvant setting 9,10. Preoperative Imatinib is recommended for large and poorly positioned GISTs, to facilitate organ preserving surgery. In the adjuvant setting, Imatinib is recommended for some intermediate and most high risk GIST tumors, as it has been shown to improve recurrence free survival (RFS) [9], [10], [11], [12]. In this case, since the tumor presented with systemic sequelae and was almost at the cut off size for the high-risk stratification, Imatinib was initiated.

The clinical presentation of GISTs is highly variable according to the tumor site and size. Common symptoms tend to be vague. Infrequent presentations result from intestinal obstruction, perforation, abscess and fistula formation 3,6,13. GISTs are capable of disrupting gastrointestinal mucosal integrity, providing a path through which colonizing bacteria gain access to the circulation. Liver abscesses can develop from hematogenous dissemination of organisms in association with systemic bacteremia, local spread of bacteria from contiguous sites of infection within the peritoneal cavity and infections within the portal vasculature 13. The treatment of hepatic abscesses usually involves drainage and intravenous antibiotics [13], [14], [15]. Several previous reports describe the association of GISTs and pyogenic liver abscesses [14], [15], [16], [17], [18]. When faced with findings of a liver lesions and an intra-abdominal mass, metastatic disease is usually highest on the differential. Pyogenic liver abscesses need to be considered, especially in those with systemic symptoms, and treatment with antibiotics instituted hastily. The patient presented in this case was immediately started on IV antibiotics, as her clinical picture suggested sepsis. Our initial impression was that the patient had metastatic disease rather than a liver abscess. Only on finding purulence during core needle biopsy of the liver lesion, was the correct diagnosis established and a percutaneous drain inserted. The reason that surgical exploration was pursued, with ongoing concern for distant disease, was because the CT scan findings were suspicious for a localized perforation. The patient's systemic symptoms and ongoing sepsis were attributed to the intra-abdominal mass, necessitating resection.

The patient we presented was found to have Streptococcus anginosus bacteremia and the same pathogen was isolated from the liver abscess. S. Anginosus is a facultative anaerobic gram-positive coccus found in the normal flora of the gastrointestinal tract and is one of the three species, with Streptococcus intermedius and Streptococcus constellatus, which constitutes the group Streptococcus milleri [14], [15], [16]. These organisms are associated with abscess formation 16. Positive blood cultures with members of the S. milleri group should prompt consideration of occult abdominal infection, perforation and gastrointestinal malignancy 15,16. Kwon et al. reported a case of a 42 year old woman with Streptococcus milleri bacteremia, liver abscess and a retroperitoneal lesion, which was found to be a duodenal GIST 17. Kurtz and Greenberg also described a patient with streptococcus milleri bacteremia, a large liver abscess and a GIST in the stomach 18. Streptococcus bovis has long been associated with colorectal cancer and endoscopic evaluation is recommended when this pathogen is found in the bloodstream 19. Streptococcus anginosus has not yet gained similar notoriety in association with gastrointestinal tract malignancies but a growing body of literature is supporting this association [14], [15], [16], [17], [18]. Unless explained by a benign intra-abdominal process, we recommend a thorough history, physical, review of systems and possible imaging and/or endoscopy for patients found to have a Streptococcus milleri infection.

4. Conclusions

We report a case of a 63 year old female with a liver abscess and an intra-abdominal mass. The patient was found to have a GIST arising from the ileum, which formed a fistula between the tumor and the small bowel lumen, providing a path for translocation of S. Anginosus into the systemic and portal circulations, resulting in bacteremia and liver abscess. The patient was appropriately treated with antibiotics, percutaneous drainage of the liver abscess and resection of the GIST. This case provides an opportunity to review a rare presentation of a GIST with liver abscess, and the management of both diseases. The significance of Streptococcus anginosus infection is reviewed and a thorough search proposed for a gastrointestinal malignancy, if presented with a systemic infection with this organism.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval from the institution's ethics committee was obtained; IRB exemption number: 7102-72-11-01

Consent

Consent from patient/family could not be obtained. Exhaustive attempts to contact patient and family were made. A formal letter from the institution was uploaded to take responsibility and to confirm that the paper has been suffiently anonymised.

Author contributions

MG − Conception of study, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the article.

BS − Management of case, revision of article, final approval of the version to be submitted.

AE – Acquisition of data, revision of article.

TD − Analysis of data, revision of article.

Registration of research studies

Study is a case report and therefore was not registered.

Guarantor

Marina Gorelik.

References

- 1.Demetri G.D., Von Mehren M., Antonescu C.R. NCCN task force report: update on the management of patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumors. J. Natl. Comprehen. Cancer Network: JNCCN. 2010;8(2):S1–S41. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2010.0116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nishida T., Goto O., Raut C.P., Yahagi N. Diagnostic and treatment strategy for small gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Cancer. 2016;122(20):3110–3118. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sorour M.A., Kassem M.I., Ghazal A.E., El-Riwini M.T., Nasr A.A. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) related emergencies. Int. J. Surg. 2014;12(4):269–280. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rubini P., Tartamella F. Primary gastrointestinal stromal tumour of the ileum pre-operatively diagnosed as an abdominal abscess. Mol. Clin. Oncol. 2016;5(5):596–598. doi: 10.3892/mco.2016.1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joensuu H., Hohenberger P., Corless C.L. Gastrointestinal stromal tumour. Lancet. 2013;382(9896):973–983. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60106-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bardell T., Jalink D.W., Hurlbut D.J., Mercer C.D. Gastrointestinal stromal tumour: varied presentation of a rare disease. Can. J. Surg. 2006;49(4):286–289. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim B.H., Lee J.H., Baik D.S. A case of malignant gastrointestinal stromal tumor of ileum with liver abscess. Korean J. Gastroenterol. 2007;50(6):393–397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Agha R.A., Fowler A.J., Saeta A., Barai I., Rajmohan S., Orgill D.P., Group S.C.A.R.E. The SCARE statement: consensus-based surgical case report guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2016;34:180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jakhetiya A., Garg P.K., Prakash G., Sharma J., Pandey R., Pandey D. Targeted therapy of gastrointestinal stromal tumours. World J. Gastrointestinal Surg. 2016;8(5):345–352. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v8.i5.345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lai E.C., Lau S.H., Lau W.Y. Current management of gastrointestinal stromal tumors–a comprehensive review. Int. J. Surg. 2012;10(7):334–340. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2012.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gold J.S., Gönen M., Gutiérrez A. Development and validation of a prognostic nomogram for recurrence-Free survival after complete surgical resection of localized, primary gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST): a retrospective analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(11):1045–1052. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70242-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeMatteo R.P., Ballman K.V., Antonescu C.R. Placebo-Controlled randomized trial of adjuvant imatinib mesylate following the resection of localized, primary gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) Lancet. 2009;373(9669):1097–1104. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60500-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shamsaeefar A., Hosseini S., Motazedian N., Razmi T. Enterocolic fistula associated with a gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Indian J. Cancer. 2009;46(3):246–247. doi: 10.4103/0019-509X.52965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johannsen E.C., Sifri C.D., Madoff L.C. Pyogenic liver abscesses. Infect. Dis. Clin. North Am. 2000;14(3):547–563. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5520(05)70120-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bonenfant F., Rousseau É., Farand P. Streptococcus anginosus pyogenic liver abscess following a screening colonoscopy. Can. J. Infect. Dis. Med. Microbiol. 2013;24(2):e45–e46. doi: 10.1155/2013/802545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Masood U., Sharma A., Lowe D., Khan R., Manocha D. Colorectal cancer associated with streptococcus anginosus bacteremia and liver abscesses. Case Rep. Gastroenterol. 2016;10(3):769–774. doi: 10.1159/000452757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kwon Y., Dang N.D., Elmunzer B.J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumor complicated by Streptococcus milleri bacteremia and liver abscess. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2009;21(7):824–826. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3282fc735c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kurtz L.E., Greenberg R.E. Pyogenic liver abscess associated with a gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the stomach. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2010;105(1):232. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chandra P., Nath S., Kumar S. Clinically occult rectal carcinoma identified in a case of streptococcus bovis endocarditis on fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography: a case report and review of literature. Ind. J. Nuclear Med. 2017;32(4):345–347. doi: 10.4103/ijnm.IJNM_71_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]