Abstract

Although mutations in more than 90 genes are known to cause CMT, the underlying genetic cause of CMT remains unknown in more than 50% of affected individuals. The discovery of additional genes that harbor CMT2-causing mutations increasingly depends on sharing sequence data on a global level. In this way—by combining data from seven countries on four continents—we were able to define mutations in ATP1A1, which encodes the alpha1 subunit of the Na+,K+-ATPase, as a cause of autosomal-dominant CMT2. Seven missense changes were identified that segregated within individual pedigrees: c.143T>G (p.Leu48Arg), c.1775T>C (p.Ile592Thr), c.1789G>A (p.Ala597Thr), c.1801_1802delinsTT (p.Asp601Phe), c.1798C>G (p.Pro600Ala), c.1798C>A (p.Pro600Thr), and c.2432A>C (p.Asp811Ala). Immunostaining peripheral nerve axons localized ATP1A1 to the axolemma of myelinated sensory and motor axons and to Schmidt-Lanterman incisures of myelin sheaths. Two-electrode voltage clamp measurements on Xenopus oocytes demonstrated significant reduction in Na+ current activity in some, but not all, ouabain-insensitive ATP1A1 mutants, suggesting a loss-of-function defect of the Na+,K+ pump. Five mutants fall into a remarkably narrow motif within the helical linker region that couples the nucleotide-binding and phosphorylation domains. These findings identify a CMT pathway and a potential target for therapy development in degenerative diseases of peripheral nerve axons.

Keywords: ATP1A1; CMT; Charcot-Marie-Tooth; genetic matchmaking; Na+,K+ ATPase; axonal neuropathy; Mendelian disease

Main Text

Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease (CMT) is a clinically and genetically heterogeneous group of peripheral motor and sensory neuropathies, affecting an estimated 1 in 2,500 individuals.1 Typical clinical features include distal weakness and atrophy, sensory loss, and absence of reflexes, although additional signs may also be present. Mutations in more than 90 genes have been associated with CMT.2, 3 For the dominant demyelinating forms (CMT1 [MIM: 118220]), the identification of the genetic cause is possible for 90% of affected individuals.4 For the dominant axonal forms (CMT2 [MIM: 609260]), however, even the most comprehensive sequencing studies fail to identify the genetic cause in ∼47%–75% of families.5 Most of the ∼40 genes carrying CMT and related disease-causing mutations, identified in the past five years, are supported by only a few families and isolated case subjects, especially for the dominant forms. Thus, the rarity of new disease-gene associations has fostered data sharing and genetic matchmaking efforts.6, 7 This study showcases the success of truly global data sharing by reporting mutations that cause dominant CMT2 in a gene not previously connected to CMT, supported by seven families, including genome-wide significant LOD scores in the two largest families.

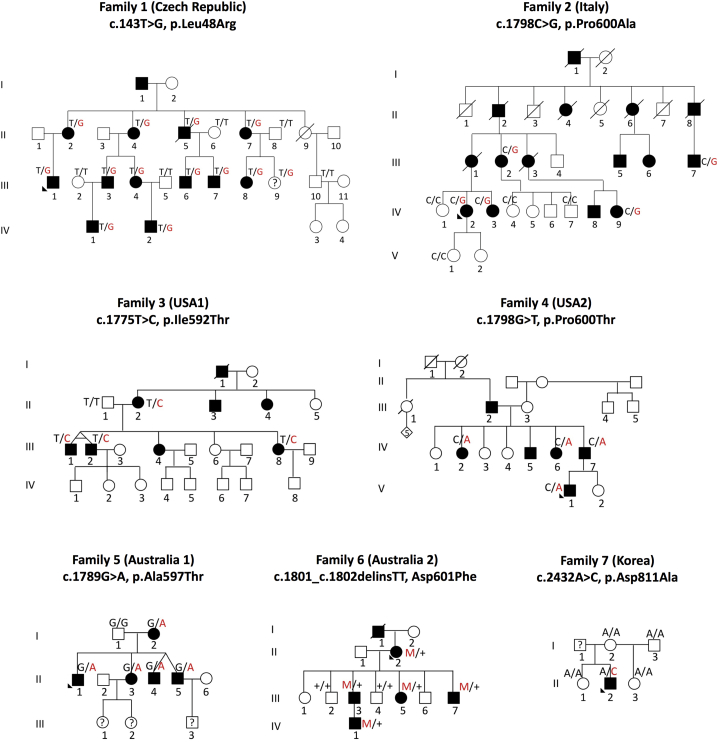

This study started with a CMT2-affected family from the Czech Republic (family 1) that had been studied for more than 14 years. The family steadily expanded to 18 members, 11 of whom were affected. Whole-exome sequencing, using Agilent SureSelect All Exon kit (Agilent) and standard Illumina HiSeq2500 sequencing, revealed a single variant in ATP1A1 (MIM: 182310) co-segregating with the disease in all affected family members as validated by Sanger sequencing (c.143T>G). We then took advantage of a large collection of 753 aggregated exomes and genomes associated with OrphaNet terms for CMT (ORPHA:166), CMT2 (ORPHA:64746), distal hereditary motor neuropathy (dHMN [ORPHA:53739]), and hereditary motor and sensory neuropathy (HMSN [ORPHA:140450]) from more than 20 independent CMT research groups within the GENESIS genome analysis platform.7 All the participants or their legal representatives had provided informed consent approved by local Research Ethics committees. In this large dataset, we first identified a rare missense change in ATP1A1 in a large family from southern Italy. Segregation of this variant was demonstrated by Sanger sequencing. After enrollment of additional family members, we were able to obtain a LOD score of 3.1 at the ATP1A1 locus. We then filtered the 753 exomes and genomes under an autosomal-dominant segregation model for minor allele frequency (MAF) in ExAC < 0.00001 and allele count in the GENESIS database < 5 in ATP1A1. Two additional missense variants (c.1798C>A and c.1775T>C) were identified and Sanger sequencing and segregation studies were performed in all available family members (Figure 1, Table 1). Independently, exome sequencing of five affected and two unaffected individuals from an Australian pedigree (family 6) identified a missense variant co-segregating with disease (c.1801_1802delGAinsTT [p.Asp601Phe]). Sanger sequencing of the hotspot exon 13 (GenBank: NM_000701) in 39 genetically unresolved Australian CMT probands identified one additional family (family 5) with an ATP1A1 variant (c.1789G>A). Family 7 was identified through the analysis of 513 whole exomes from 399 unrelated Korean CMT-affected families. Complete segregation analysis was not possible as the proband’s father is deceased; he died in his sixth decade of life without any CMT clinical symptoms. Finally, 80 Taiwanese families with genetically unresolved CMT2 were screened for ATP1A1 mutations, but no further cases were identified. In total, we confirmed the following ATP1A1 variants in families from four continents: family 1 (Czech), c.143T>G (p.Leu48Arg) (chr1:116927424); family 2 (Italy), c.1798C>G (p.Pro600Ala) (chr1:116937869); family 3 (USA), c.1775T>C (p.Ile592Thr) (chr1:116937846); family 4 (USA), c.1798C>A (p.Pro600Thr) (chr1:116937869); family 5 (Australia), c.1789G>A (p.Ala597Thr) (chr1:116937860); family 6 (Australia), c.1801_1802delGAinsTT (p.Asp601Phe) (chr1:116937872); and family 7 (South Korea), c.2432A>C (p.Asp811Ala) (chr1:116941690) (Figures 1 and 2, Table 1). All reported mutations were absent from >240,000 chromosomes in the gnomAD database, were highly conserved across species, were predicted to be protein damaging, and were conserved across all four different ATP1A paralogs (in the literature also described as ATP1A isoforms) (Figure 2B, Table S2).

Figure 1.

Pedigrees of Families Carrying Mutations in ATP1A1

Autosomal-dominant CMT-affected families show segregation of ATP1A1 variants: family 1 (Czech Republic), family 2 (Italy), family 3 (USA1), family 4 (USA2), family 5 (Australia1), family 6 (Australia2), and family 7 (Korea).

Table 1.

ATP1A1 Mutations Detected in CMT2 and CMT Dominant-Intermediate Families

| Families (Origin) | gDNA Level: Chr1(GRCh37) | cDNA Level: NM_001160233.1 | Protein Level | Exon |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family 1 (Czech Republic) | g.116927424T>G | c.143T>G | p.Leu48Arg | 5 |

| Family 2 (Italy) | g.116937869C>G | c.1798C>G | p.Pro600Ala | 13 |

| Family 3 (USA 1) | g.116937846T>C | c.1775T>C | p.Ile592Thr | 13 |

| Family 4 (USA 2) | g.116937869C>A | c.1798C>A | p.Pro600Thr | 13 |

| Family 5 (Australia 1) | g.116937860G>A | c.1789G>A | p.Ala597Thr | 13 |

| Family 6 (Australia 2) | g.116937872_116937873delinsTT | c.1801_1802delinsTT | p.Asp601Phe | 13 |

| Family 7 (Korea) | g.116941690A>C | c.2432A>C | p.Asp811Ala | 19 |

Figure 2.

ATP1A1 Mutations Identified in CMT-Affected Families

(A) Schematic depicting the position of pathogenic substitutions in the ATP1A1 protein and their associated locations around the globe.

(B) ATP1A protein paralogs alignment showing that the ATP1A1 substitutions are located at highly conserved residues across the four different paralogs.

(C) 3D structural model of ATP1A1.

(D) Electron micrograph of a sural nerve biopsy of affected individual from family 7 (Korea) showing typical signs of chronic axonal degeneration.

Neurological examination and electromyography were performed in 30 individuals across 5 of the studied families (Tables 2 and S1). We observed distal weakness in the legs and arms with normal proximal strength in virtually all subjects. Vibratory sensation was typically reduced in the legs and also in the hands in some individuals. The age of symptom onset was variable, ranging from childhood to adult, even within the same family. Several mutation-carrying subjects had normal neurological examinations into the fifth decade of life, but had clear abnormalities in their nerve conduction studies (NCSs). NCSs, when performed, demonstrated reduced compound muscle action potential (CMAP) and sensory nerve actions potential (SNAP) amplitudes with preserved conduction velocity diagnostic of axonal sensorimotor neuropathies (Table 2). CMT neuropathy scores v.2 (CMTNSv2) ranged from mild 6 to severely affected 25.8, 9 Many subjects presented with pes cavus foot structure (see Supplemental Note).

Table 2.

Clinical Features Observed in ATP1A1 Individuals

| Individual | Age (y) | AOO | CMTNSv2 (Rasch) | Distal Weakness UL | Proximal Weakness UL | Distal Weakness LL | Proximal Weakness LL | Vibration UL | Vibration LL | Foot Deformity | Reflexes UL (Biceps/Triceps) | Reflexes LL (Patellar/Achilles) | Positive Sensory Symptoms | Other Clinical Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family 1 | ||||||||||||||

| II:5 | 66 | 20 | 12 (CMTES) | 2,3,2 | 5,5,5 | 0,0 | 5,5 | 6/8 (fingers) | 2/8 (ankle) | pes cavus | normal/normal | decreased/decreased | none | none |

| III:6 | 33 | 13 | 7 (CMTES) | 2,3,2 | 5,5,5 | 0,0 | 5,5 | normal (8/8) | normal (8/8) | pes cavus | decreased/decreased | decreased/absent | none | none |

| III:7 | 28 | 18 | 7 (CMTES) | 3,3,3 | 5,5,5 | 1,1 | 5,5 | normal (8/8) | normal (8/8) | none | normal/normal | decreased/absent | none | none |

| II:2 | 71 | 12 | 14 (CMTES) | 2,2,2 | 5,5,5 | 0,0 | 5,5 | normal (8/8) | 0/8 | none | absent/absent | absent/absent | none | none |

| III:1 | 42 | 25 | 8 (CMTES) | 5,4,5 | 5,5,5 | 0,0 | 5,5 | 0/8 (fingers) | 5/8 (ankle) | none | decreased/absent | absent/absent | none | none |

| 55 | 13 (CMTES) | 4,4−,4− | 5,5,5 | 0,0 | 5,5 | 6/8 (fingers) | 2/8 (ankle) | none | absent/absent | absent/absent | none | uses crutches intermittently | ||

| II:4 | 68 | 50 | 10 (CMTES) | 4,4,4 | 5,5,5 | 3,3 | 5,5 | normal (8/8) | 5/8 (ankle) | pes cavus | decreased/decreased | absent/absent | none | none |

| III:3 | 32 | no | 0 (CMTES) | 5,5,5 | 5,5,5 | 5,5 | 5,5 | normal (8/8) | normal (8/8) | none | normal/normal | decreased/decreased | none | none |

| 45 | 0 (CMTES) | 5,5,5 | 5,5,5 | 5,5 | 5,5 | 7/8 (fingers) | 7/8 (ankle) | shortened Achilles | decreased/absent | absent/absent | none | none | ||

| III:4 | 47 | 35 | 5 (CMTES) | 5,4+,4 | 5,5,5 | 4,5 | 5,5 | N/A | N/A | pes cavus | absent/absent | absent/absent | +; toes | none |

| 59 | 8 (CMTES) | 4,4,4 | 5,5,5 | 2,3 | 5,5 | 7/8 (fingers) | 4/8 (ankle) | pes cavus | absent/absent | absent/absent | none | none | ||

| II:7 | 63 | no | 3 (CMTES) | 4+,4, 4+ |

5,5,5 | 5,5 | 5,5 | 7/8 (fingers) | 6/8 (ankle) | none | decreased/absent | absent/absent | none | none |

| III:8 | 45 | no | 0 (CMTES) | 5,5,5 | 5,5,5 | 5,5 | 5,5 | 7/8 (fingers) | 6/8 (ankle) | shortened Achilles | normal/normal | normal/absent | none | none |

| IV:1 | 25 | no | 0 (CMTES) | 5,5,5 | 5,5,5 | 5,5 | 5,5 | N/A | 7/7 | pes planus | normal/normal | normal/decreased | none | none |

| Family 2 | ||||||||||||||

| III.2 | 69 | 30 | 19 (23) | 4,4,4 | 5,5,5 | 1,1 | 4,4 | normal | red toe | none | normal/normal | absent/absent | none | none |

| III.7 | 59 | 50 | 14 (17) | 4,4,4 | 5,5,5 | 4,5 | 5,5 | normal | red knee | pes cavus | normal/normal | normal/normal | none | none |

| IV.2 | 44 | 30 | 15 (21) | 4,4,4 | 5,5,5 | 1,4 | 5,5 | normal | red knee | pes cavus | normal/normal | absent/absent | none | nasal voice |

| IV.3 | 41 | 30 | 12 (17) | 4,4,4 | 5,5,5 | 3,4 | 5,5 | normal | red ankle | none | normal/decreased | normal/absent | none | none |

| IV.9 | 20 | 13 | 16 (18) | 5,5,5 | 5,5,5 | 3,4 | 5,5 | normal | red knee | pes cavus | normal/absent | absent/absent | none | none |

| Family 4 | ||||||||||||||

| 76014-1000 | 33 | 12 | 19 (26) | 4−,3,3 | 5,5,5 | 0,4 | 5,5 | reduced L side, normal R side | absent ankle | pes cavus | normal/normal | absent/absent | + | severe headaches, dizziness, swallow/GI issues, pulmonary issues, can’t sleep on back |

| 76014-1002 | 45 | 30 s | 15 (20) | 4+,4+,3 | 5,4+,4+ | 4,4+ | 5,5 | normal | absent ankle, red knee | pes planus | absent/absent | reduced/absent | none | dizziness, swallow/GI issues |

| 76014-1006 | 36 | 31 | 6 (6) | 5,5,5 | 5,5,5 | 5,5 | 5,5 | normal | normal | none | normal/normal | normal/absent | + | tripping, foot drop, no hand issues |

| Family 6 | ||||||||||||||

| 542_II:2 | 61 | 9 | 25 | 0,5 | 5,5 | 0 | 5,5 | absent in fingers | absent to knee | pes cavus | reduced | absent | none | none |

| 542_III:3 | 55 | 10 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | absent in fingers | absent to mid shin | pes cavus | reduced | absent | none | none |

| 542_III:6 | 30 | 12 | ND | 2 | 5,5,5 | 0 | 5,5 | absent in fingers | absent to mid shin | pes cavus | reduced | absent | none | none |

| 542_III:9 | 26 | 11 | ND | 2 | 5,5,5 | 0 | 5,5 | absent in fingers | absent to mid shin | pes cavus | reduced | absent | none | none |

| 542_IV:1 | 10 | 8 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | pes cavus | normal | reduced | none | none |

| 3074_I:2 | 88 | 36 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | absent in fingers | absent to mid shin | pes cavus | reduced | absent | none | none |

| 3074_II:1 | 66 | 25 | 21 | 3 | 5,5,5 | 0 | 5,5 | absent in fingers | absent to mid shin | pes cavus | reduced | absent | none | none |

| 3074_II:3 | 64 | 32 | ND | 4 | 5,5,5 | 2 | 5,5 | normal | absent to ankle | pes cavus | normal | absent | none | none |

| 3074_II:4 | 59 | 21 | ND | 4 | 5,5,5 | 4 | 5,5 | normal | absent to ankle | pes cavus | reduced | none | none | none |

| 3074_II:5 | 59 | 25 | ND | 4 | 5,5,5 | 4 | 5,5 | normal | absent to ankle | pes cavus | reduced | absent | none | none |

| Family 7 | ||||||||||||||

| II:2 | 33 | 18 | 22 | 0,0,0 | 5,5,5 | 0,0 | 5,5 | absent in fingers | absent to ankle | pes cavus | absent/absent | absent/absent | + | gait ataxia, hand muscle atrophy, uses AFOs |

Abbreviations are as follows: AOO, age of onset; CMTES, CMT exam score; LL, lower limb; ND, no data; UL, upper limb. Motor weakness based on MRC scale (0–5): plus sign (+) indicates weakness present; minus sign (−) indicates no weakness detected/no problems. LL distal weakness assessed by anterior tibialis and gastrocnemius, LL proximal weakness assessed by ilio psoas and quadriceps; UL distal weakness assessed by first dorsal interosseous, abductor pollicis brevis, and adductor digiti minimi, UL proximal weakness assessed by deltoids, biceps brachii, and triceps. Vibration based on Rydell tuning fork with “5” on scale of “8” being considered normal and cutaneous based on pinprick sensation: normal is no decrease compared to the examiner; “red” indicates reduced. Both motor and sensory evaluations were based on worst score observed of the two limbs. CMTNSv2 scores are separable into <10 (mild), 11–20 (moderate), or >20 (severe) impairment.8 In Family 6, distal weakness was measured in a single muscle group resulting in a single MRC score for the distal upper and lower limbs.

A sural nerve biopsy was available from a 33-year-old affected individual (family 7), who carried the functionally most severe change p.Asp811Ala. As shown in Figure 2D, there was a pronounced loss of large myelinated fibers, groups of regenerating axons, and a number of thinly myelinated large axons were present. No signs of inflammation were observed. These findings are indicative of an axonal peripheral neuropathy and in agreement with the electrophysiological findings in this individual.

ATP1A1 encodes the α1 subunit of the Na+,K+-ATPase, a protein ion pump responsible for the active transport of Na+ and K+ across the plasma membrane, powered by the hydrolysis of ATP, to maintain the Na+ and K+ chemical gradients in the cell.10 There are four α paralogs encoded by different genes (ATP1A1-4), and each has distinct tissue-specific expression. Mutations in ATP1A2 (MIM: 182340) and ATP1A3 (MIM: 182350) are known to cause distinct neurological disorders of the central nervous system, likely through a haploinsufficiency mechanism of action.11, 12 Mutations in ATP1A1 have not been associated with any human monogenic disease to date. Four of the identified substitutions (p.Ile592Thr, p.Pro600Thr, p.Pro600Ala, and p.Asp601Phe) are clustered in the intracellular loop between transmembrane domains M4 and M5 (Figure 2A), a region where ATP binding and ATP hydrolysis occur. The substitution p.Leu48Arg is located adjacent to a phosphorylation site in the N terminus region, and p.Asp811Ala is located in the fifth transmembrane domain where Na+ binding occurs. The corresponding substitution in ATP1A2 (p.Asp801Asn) has been reported in several individuals with alternating hemiplegia of childhood and rapid-onset dystonia parkinsonism diseases.12, 13

ATP1A1 is highly constrained (intolerant) for missense and loss-of-function (LoF) variations as calculated by the correlation between observed and expected number of variants.14 Derived from ExAC, the expected number of missense variants for ATP1A1 is 357.8, but the observed number of variants is only 91 (Z-score = 6.9) (Figure 3A, Table S3). The number of loss-of-function variants is also low, leading to the maximum constraint metric for probability of LoF intolerance (pLI = 1.00) (Figure 3B).14 Other dominant CMT-associated genes are also significantly more constrained than recessive CMT-associated genes (Figure 3C). Interestingly, ATP1A1 has the second highest constraint value of genes associated with CMT, behind DYNC1H1 (MIM: 600112) (Z-score = 13.88). In fact, ATP1A1 is ranked number 31 of all genes in the human genome.14 Two other disease-associated ATP1A genes (ATP1A2 and ATP1A3) also show high intolerance against rare missense variation, but ATP1A4 does not. This further supports the potential for variations in ATP1A1 to cause disease.

Figure 3.

Genetic and Functional Studies of ATP1A1

(A and B) Mutational constraint analysis of ATP1A genes and known CMT-associated genes. ATP1A1, ATP1A2, and ATP1A3 have high missense constraint scores (A) and pLI (probability of LoF intolerance) (B); obtained from the ExAC browser.

(C) Dominant CMT-associated genes have significantly higher constraint (more intolerant) scores for missense variants than recessive CMT-associated genes.

(D) Two electrodes voltage clamp (TEVC) recordings at −50 mV from different CMT-associated mutations in the α1 subunit. For comparison, currents through wild-type α1 are shown in black. Dashed lines represent zero current. Summary of currents from the CMT-associated mutations shown are normalized to WT currents (mean ± SEM; n = 5–7; p < 0.05).

(E) Ouabain survival assay of U2OS cells treated with 0.5 μM ouabain. Cell viability represents the luminescence values obtained from the CellTiter-Glo assay (n = 8; t test p < 0.05 compared to oua-WT-ATP1A1).

(F) Distinct localization of α1 and α3 in myelinated axons. These are confocal images of teased fibers from an adult rat, immunostained with a mouse monoclonal antibody against α3 (XVIF9-G10; red), and a rabbit antiserum against α1 (NASE; green), as indicated. Two myelinated axons (1,3) have strong α3 staining (and weak α1 staining), and a myelinated axon (4) has strong α1 staining (and weak α3 staining). The incisures of myelin sheaths are α1-positive (inset). A Remak bundle (2) is α1-positive and α3-negative. Apposed arrowheads mark nodes of Ranvier. Scale bar: 10 μm.

ATP1A1 is the catalytic α subunit of a P-type Na+,K+-ATPase ion pump that establishes Na+ and K+ gradients across cell membranes. As with other members of the P-type ATPase superfamily, ion pumping by ATP1A1 is achieved by alternating between two major conformational states that are controlled by ATP hydrolysis and intermediate phosphorylation to regulate the binding, occlusion, and transport of cations into (K+) and out (Na+) of the cell.15 Crystallographic studies have established that ATP1A1 consists of ten transmembrane helices and three cytoplasmic domains, individually known as the N (nucleotide binding), P (phosphorylation), and A (actuator) domains (Figure 2C).15, 16

We examined these crystal structures to assess the potential structure-function consequences of the seven unique segregating missense changes that we identified in ATP1A1 (Figure 2C). Remarkably, five substitutions (p.Ile592Thr, p.Ala597Thr, p.Pro600Ala, p.Pro600Thr, and p.Asp601Phe) map to a hotspot within the helical linker region (residues 592 to 608) that couples the N and P domains (red linker in Figure 2C). These changes likely de-couple ATP hydrolysis (N domain) from intermediate phosphorylation (P domain) that is essential for ion selectivity and driving the two major alternating conformations of the pump. Only one substitution (p.Leu48Arg) maps to the actuator domain, where it could disrupt the concerted movement of the N, P, and A domains during phosphorylation and pumping. The remaining change, p.Asp811Ala, maps to the transmembrane channel core, where it likely disrupts Na+ binding and transport through the membrane. From this analysis, we conclude that the helical linker region between the N and P domains is a hotspot for mutational defects in the ATP1A1 pump. However, our observation of additional mutations elsewhere in ATP1A1 indicate that pathogenic changes are not necessarily localized to a specific region of the pump. This latter observation makes intuitive sense given the long-distance allosteric changes that regulate this complex molecular machine.

To test the functional effects of the different CMT-associated ATP1A1 mutations, we examined the electrophysiological characteristics of human wild-type (WT) ATP1A1 and the different ATP1A1 variants (co-expressed with the human β1 subunit) in Xenopus oocytes. Two studied CMT substitutions, p.Pro600Ala and p.Asp811Ala, demonstrated significantly fewer Na+-dependent currents than WT-ATP1A (Figure 3D). This was especially pronounced for the p.Asp811Ala substitution, in agreement with previous experiments that demonstrated alteration of the homologous residue leads to defective Na+ binding in other ATP1A proteins.17 Asp811 is predicted to coordinate Na+ ions in the crystal structures of Na+,K+ ATPases, thus missense variants are potentially resulting in the loss of sodium ion coordination. Substitution p.Pro600Ala also showed significantly reduced Na+-dependent currents (Figure 3D). This residue falls into a proposed molecular hinge between the N and P domains.18 Substitutions of Pro600 might therefore affect the ability of ATP1A1 to undergo conformational changes during Na+/K+ transport. The p.Leu48Arg substitution showed similar Na+-dependent currents as WT-ATP1 (Figure 3D), suggesting that this substitution causes functional defects that are not detected in this assay (i.e., protein stability) or defects that are masked in the Xenopus oocyte expression system, such as cellular trafficking. Mutations that cause trafficking defects in mammalian expression systems are often still trafficked to the plasma membrane in Xenopus oocytes, possibly due to the lower culture temperatures for Xenopus oocytes.19

To further evaluate the functional consequences of the CMT-associated ATP1A1 variants in mammalian cells, we performed an ouabain survival assay in U2OS cells. Cells were transfected with plasmids encoding full-length human ATP1A1 (WT-ATP1A1) and an ATP1A1 construct that had been mutated to be ouabain insensitive (Oua-WT). Cells transfected to express Oua-WT and selected mutants (Oua-p.Leu48Arg, Oua-p.Ile592Thr, Oua-p.Pro600Thr, and Oua-p.Asp811Ala) were treated with 0.5 μM ouabain for 48 hr. Cell death was observed in WT-ATP1A1 cells, whereas cells transfected with the Oua-WT survived. Cell viability assays were quantified using the CellTiter-Glo assay. We observed a significant decrease in cell viability in cells transfected with plasmids encoding the ouabain-insensitive mutants Oua-p.Leu48Arg, Oua-p.Ile592Thr, Oua-p.Pro600Thr, and Oua-p.Asp811Ala (Figure 3E). The mutant Oua-p.Asp811Ala seems to be the most severely affected, in the least number of viable cells. Likewise, it has been demonstrated that cells ectopically expressing pathogenic ATP1A3 mutants show a higher percentage of cell death compared to those expressing wild-type ATP1A3.20 Thus, the ouabain survival assay further supports a detrimental functional effect of the identified substitutions.

To investigate why ATP1A1 mutations cause an axonal neuropathy, we evaluated the protein levels of ATP1A1 in the peripheral nervous system using mouse monoclonal antibodies against ATP1A1 and ATP1A3 (Figures 3F and S1).21, 22 Immunostaining of teased fibers from adult rat sciatic nerve (Figure 3F) shows that individual axons are variably ATP1A1 and ATP1A3 positive: some axons are mainly positive for one or the other, but most axons show detectable levels of both. ATP1A1 is also localized to Schwann cells, particularly paranodes and Schmidt-Lanterman incisures, which are regions of non-compact myelin that are thought to facilitate the diffusion of small molecules and ions.23 Immuno-stained cryosections of adult rat spinal cord (Figure S1) show that ATP1A3 is the main ATP1A paralog localized in the central nervous system, a subset of large sensory axons that are known to be proprioceptors, and small myelinated axons of γ-motor neurons.24, 25, 26 ATP1A1 was the predominant ATP1A paralog present in most the motor and sensory axons of the ventral and dorsal roots. In addition, the large motor neurons of the ventral horn are also ATP1A1 positive. Thus, most peripheral nerve axons and all Schwann cells contain ATP1A1, indicating that ATP1A1 mutations could cause an axonal neuropathy by affecting the function of ATP1A1 in one or both cell types.

The membrane-bound ATP1A1 is present at high levels in α-motoneurons and most sensory neurons.27 In peripheral nerve, ATP1A1 localizes to axons (internodal axolemma) and non-compact myelin (Schmidt-Lanterman incisures and paranodes). The demonstrated reduction in Na+,K+-ATPase activity in ATP1A1 mutants will potentially reduce the Na+ gradient across the axonal membrane, as has been shown in other Na+,K+-ATPase mutations.28 This reduced Na+ gradient would lead to a reduced efflux of Ca2+ from the axon by Na+/Ca2+ exchangers and potentially even a Ca2+ influx through Na+/Ca2+ exchangers. As has been shown at nodes during repetitive firing, this leads to influx of Ca2+ through Na+/Ca2+ exchangers at the nodes of WT mouse peripheral motor axons.29 Thus, the reduction in Na+,K+-ATPase activity would lead to a build-up of toxic levels of intracellular Ca2+.13 This offers a pathomechanism for CMT, which will likely yield additional disease-causing genetic factors.

Two other paralogs of ATP1A have been shown to cause neurological disease. We hypothesize that the distinctive phenotypes associated with ATP1A proteins results from differential tissue localization patterns and redundancy of local function. For instance, ATP1A2 and ATP1A3 are expressed predominantly in the central nervous system and mutations have been associated with familial hemiplegic migraine and dystonia and parkinsonism.20, 30 Reduced activity of Na+,K+-ATPase activity in ATP1A2 and ATP1A3 mutants has been shown, indicating haploinsufficiency and loss-of-function mechanism of action.12, 31 ATP1A1 substitutions may act in a similar fashion as supported by our voltage clamp experiments. However, as not all tested substitutions showed reduced Na+,K+-ATPase activity, additional mechanisms such as trafficking defects may be revealed in future studies. The identified missense mutations in our study span the gene, with a prominent cluster between residue 592 and 601. Of interest, the large gnomAD database does not record any missense variant alleles between residues 590 and 638 in more than ∼240,000 chromosomes.

In our study, ATP1A1 substitutions were associated with a classic axonal to intermediate length-dependent degeneration of motor and sensory peripheral nerves. We predict that as more affected individuals are screened for variants in ATP1A1, the phenotypic spectrum may expand. Given that ATP1A proteins are ubiquitously present at low levels, a combination of central and peripheral phenotypes is conceivable in some families. We fully expect that extra-PNS features will appear in affected individuals, as we have already noted anecdotally in family 3 with migraine headaches.

Taken together, we show that ATP1A1 mutations are a cause for dominant axonal to intermediate CMT. This conclusion is supported by strong genetic evidence in seven families, structural protein analysis, comparative molecular genetics evidence, in vitro and in vivo functional experiments, and histological studies. These mutations likely act through haploinsufficiency, similar to changes in ATP1A2 and ATP1A3. This CMT pathway offers therapeutic target considerations. The international collaborative nature of this study was enabled by data aggregation and genetic matchmaking capabilities of the GENESIS platform, spanning four continents and five countries.7

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by MH CR AZV 16-30206A and DRO 00064203 (to P.L. and P.S.); Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Fellowship APP1117510 (to N.L.); Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Fellowship APP1122952 (to G.R.); NHMRC Project Grant APP1080587 (to N.L.), NIH (RO1 NS43174, U54 NS065712 to S.S.S.; RO1 NS094388 to B.-O.C.; R01 GM109762, R01 HL131461 to H.P.L.; K01 NS096778 to R.B.-S.; R01NS075764, U54NS065712, and U54NS092091 to S.Z.; U54 NS065712 to M.S.; R35 GM119518 to D.G.I.), Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan (105-2628-B-075-002-MY3 to Y.-C.L.), the Judy Seltzer Levenson Memorial Fund for CMT Research, the Charcot-Marie-Tooth Association, and the Muscular Dystrophy Association. We thank C. Kleinberg and Dr. E. Arroyo for confocal images and Dr. Pressley for the rabbit antiserum against ATP1A1. We thank Dr. Pablo Artigas for the human wild-type ATP1A1 and beta1 subunits for Xenopus oocyte expression and help with Xenopus oocyte recordings.

Published: February 22, 2018

Footnotes

Supplemental Data include one figure, three tables, and Supplemental Note (case reports) and can be found with this article online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2018.01.023.

Web Resources

ExAC Browser, http://exac.broadinstitute.org/

gnomAD Browser, http://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/

HGMD Professional, http://www.biobase-international.com/product/hgmd

Likelihood Ratio Test, http://www.genetics.wustl.edu/jflab/lrt_query.html

MutationTaster, http://www.mutationtaster.org/

OMIM, http://www.omim.org/

PROVEAN, http://provean.jcvi.org

Supplemental Data

References

- 1.Skre H. Genetic and clinical aspects of Charcot-Marie-Tooth’s disease. Clin. Genet. 1974;6:98–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1974.tb00638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Timmerman V., Strickland A.V., Züchner S. Genetics of Charcot-Marie-Tooth (CMT) disease within the frame of the Human Genome Project success. Genes (Basel) 2014;5:13–32. doi: 10.3390/genes5010013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pareyson D., Saveri P., Pisciotta C. New developments in Charcot-Marie-Tooth neuropathy and related diseases. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2017;30:471–480. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0000000000000474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fridman V., Bundy B., Reilly M.M., Pareyson D., Bacon C., Burns J., Day J., Feely S., Finkel R.S., Grider T., Inherited Neuropathies Consortium CMT subtypes and disease burden in patients enrolled in the Inherited Neuropathies Consortium natural history study: a cross-sectional analysis. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 2015;86:873–878. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2014-308826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rossor A.M., Polke J.M., Houlden H., Reilly M.M. Clinical implications of genetic advances in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2013;9:562–571. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2013.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Philippakis A.A., Azzariti D.R., Beltran S., Brookes A.J., Brownstein C.A., Brudno M., Brunner H.G., Buske O.J., Carey K., Doll C. The Matchmaker Exchange: a platform for rare disease gene discovery. Hum. Mutat. 2015;36:915–921. doi: 10.1002/humu.22858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gonzalez M., Falk M.J., Gai X., Postrel R., Schüle R., Zuchner S. Innovative genomic collaboration using the GENESIS (GEM.app) platform. Hum. Mutat. 2015;36:950–956. doi: 10.1002/humu.22836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murphy S.M., Herrmann D.N., McDermott M.P., Scherer S.S., Shy M.E., Reilly M.M., Pareyson D. Reliability of the CMT neuropathy score (second version) in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. J. Peripher. Nerv. Syst. 2011;16:191–198. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8027.2011.00350.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shy M.E., Blake J., Krajewski K., Fuerst D.R., Laurá M., Hahn A.F., Li J., Lewis R.A., Reilly M. Reliability and validity of the CMT neuropathy score as a measure of disability. Neurology. 2005;64:1209–1214. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000156517.00615.A3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morth J.P., Pedersen B.P., Buch-Pedersen M.J., Andersen J.P., Vilsen B., Palmgren M.G., Nissen P. A structural overview of the plasma membrane Na+,K+-ATPase and H+-ATPase ion pumps. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2011;12:60–70. doi: 10.1038/nrm3031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vanmolkot K.R.J., Kors E.E., Hottenga J.-J., Terwindt G.M., Haan J., Hoefnagels W.A.J., Black D.F., Sandkuijl L.A., Frants R.R., Ferrari M.D., van den Maagdenberg A.M. Novel mutations in the Na+, K+-ATPase pump gene ATP1A2 associated with familial hemiplegic migraine and benign familial infantile convulsions. Ann. Neurol. 2003;54:360–366. doi: 10.1002/ana.10674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heinzen E.L., Swoboda K.J., Hitomi Y., Gurrieri F., Nicole S., de Vries B., Tiziano F.D., Fontaine B., Walley N.M., Heavin S., European Alternating Hemiplegia of Childhood (AHC) Genetics Consortium. Biobanca e Registro Clinico per l’Emiplegia Alternante (I.B.AHC) Consortium. European Network for Research on Alternating Hemiplegia (ENRAH) for Small and Medium-sized Enterpriese (SMEs) Consortium De novo mutations in ATP1A3 cause alternating hemiplegia of childhood. Nat. Genet. 2012;44:1030–1034. doi: 10.1038/ng.2358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holm T.H., Lykke-Hartmann K. Insights into the pathology of the α3 Na(+)/K(+)-ATPase ion pump in neurological disorders; lessons from animal models. Front. Physiol. 2016;7:209. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2016.00209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lek M., Karczewski K.J., Minikel E.V., Samocha K.E., Banks E., Fennell T., O’Donnell-Luria A.H., Ware J.S., Hill A.J., Cummings B.B., Exome Aggregation Consortium Analysis of protein-coding genetic variation in 60,706 humans. Nature. 2016;536:285–291. doi: 10.1038/nature19057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bublitz M., Poulsen H., Morth J.P., Nissen P. In and out of the cation pumps: P-type ATPase structure revisited. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2010;20:431–439. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2010.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kanai R., Ogawa H., Vilsen B., Cornelius F., Toyoshima C. Crystal structure of a Na+-bound Na+,K+-ATPase preceding the E1P state. Nature. 2013;502:201–206. doi: 10.1038/nature12578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pedersen P.A., Rasmussen J.H., Nielsen J.M., Jorgensen P.L. Identification of Asp804 and Asp808 as Na+ and K+ coordinating residues in alpha-subunit of renal Na,K-ATPase. FEBS Lett. 1997;400:206–210. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(96)01381-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Friedrich T., Tavraz N.N., Junghans C. ATP1A2 mutations in migraine: seeing through the facets of an ion pump onto the neurobiology of disease. Front. Physiol. 2016;7:239. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2016.00239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anderson C.L., Delisle B.P., Anson B.D., Kilby J.A., Will M.L., Tester D.J., Gong Q., Zhou Z., Ackerman M.J., January C.T. Most LQT2 mutations reduce Kv11.1 (hERG) current by a class 2 (trafficking-deficient) mechanism. Circulation. 2006;113:365–373. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.570200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Carvalho Aguiar P., Sweadner K.J., Penniston J.T., Zaremba J., Liu L., Caton M., Linazasoro G., Borg M., Tijssen M.A.J., Bressman S.B. Mutations in the Na+/K+ -ATPase alpha3 gene ATP1A3 are associated with rapid-onset dystonia parkinsonism. Neuron. 2004;43:169–175. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arystarkhova E., Sweadner K.J. Isoform-specific monoclonal antibodies to Na,K-ATPase alpha subunits. Evidence for a tissue-specific post-translational modification of the alpha subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:23407–23417. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.38.23407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pressley T.A. Ionic regulation of Na+,K(+)-ATPase expression. Semin. Nephrol. 1992;12:67–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scherer S.S., Xu Y.-T., Messing A., Willecke K., Fischbeck K.H., Jeng L.J.B. Transgenic expression of human connexin32 in myelinating Schwann cells prevents demyelination in connexin32-null mice. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:1550–1559. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3082-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McGrail K.M., Phillips J.M., Sweadner K.J. Immunofluorescent localization of three Na,K-ATPase isozymes in the rat central nervous system: both neurons and glia can express more than one Na,K-ATPase. J. Neurosci. 1991;11:381–391. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-02-00381.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dobretsov M., Hastings S.L., Sims T.J., Stimers J.R., Romanovsky D. Stretch receptor-associated expression of alpha 3 isoform of the Na+, K+-ATPase in rat peripheral nervous system. Neuroscience. 2003;116:1069–1080. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00922-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Edwards I.J., Bruce G., Lawrenson C., Howe L., Clapcote S.J., Deuchars S.A., Deuchars J. Na+/K+ ATPase α1 and α3 isoforms are differentially expressed in α- and γ-motoneurons. J. Neurosci. 2013;33:9913–9919. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5584-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kleinberg, S.C., Arroyo, J.E., Chih, K., and Scherer, S.S. (2007). Na, K-ATPase isoforms in the PNS: Cell-type specific expression and internodal localization in myelinated axons. ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/295221155_Na_K-ATPase_isoforms_in_the_PNS_Cell-type_specific_expression_and_internodal_localization_in_myelinated_axons.

- 28.Toustrup-Jensen M.S., Einholm A.P., Schack V.R., Nielsen H.N., Holm R., Sobrido M.-J., Andersen J.P., Clausen T., Vilsen B. Relationship between intracellular Na+ concentration and reduced Na+ affinity in Na+,K+-ATPase mutants causing neurological disease. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:3186–3197. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.543272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang Z., David G. Stimulation-induced Ca(2+) influx at nodes of Ranvier in mouse peripheral motor axons. J. Physiol. 2016;594:39–57. doi: 10.1113/JP271207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Fusco M., Marconi R., Silvestri L., Atorino L., Rampoldi L., Morgante L., Ballabio A., Aridon P., Casari G. Haploinsufficiency of ATP1A2 encoding the Na+/K+ pump α2 subunit associated with familial hemiplegic migraine type 2. Nat. Genet. 2003;33:192–196. doi: 10.1038/ng1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Todt U., Dichgans M., Jurkat-Rott K., Heinze A., Zifarelli G., Koenderink J.B., Goebel I., Zumbroich V., Stiller A., Ramirez A. Rare missense variants in ATP1A2 in families with clustering of common forms of migraine. Hum. Mutat. 2005;26:315–321. doi: 10.1002/humu.20229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.