Abstract

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a rod-shaped Gram-negative bacterium which is notably known as a pathogen in humans, animals, and plants. Infections caused by P. aeruginosa especially in hospitalized patients are often life-threatening and rapidly increasing worldwide throughout the years. Recently, multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa has taken a toll on humans’ health due to the inefficiency of antimicrobial agents. Therefore, the rapid and advanced diagnostic techniques to accurately detect this bacterium particularly in clinical samples are indeed necessary to ensure timely and effective treatments and to prevent outbreaks. This review aims to discuss most recent of state-of-the-art molecular diagnostic techniques enabling fast and accurate detection and identification of P. aeruginosa based on well-developed genotyping techniques, e.g., polymerase chain reaction, pulse-field gel electrophoresis, and next generation sequencing. The advantages and limitations of each of the methods are also reviewed.

Keywords: molecular diagnostics, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, polymerase chain reaction, pulse-field gel electrophoresis, next generation sequencing

Introduction

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a common environmental microorganism which is widespread in nature. It is a ubiquitous Gram-negative bacterium which increasingly recognized as an emerging opportunistic pathogen of clinical relevance due to its high morbidity and mortality infection rate in healthcare settings especially among immunocompromised individuals and other highly vulnerable patients. P. aeruginosa has been classified as an ESKAPE (Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, P. aeruginosa, and Enterobacter species) pathogen; one of the six highly antibiotic resistant bacteria (Rice, 2008). It is also listed as a critical priority pathogen “for which new antibiotics are urgently needed" by World Health Organization [WHO], 2017. The detection of P. aeruginosa at early aggressive antibiotic treatment is significant in order to prevent or to postpone chronic lung colonization for cystic fibrosis patients (Starner and McCray, 2005; Deschaght et al., 2011; Douraghi et al., 2014) and burn infections which could lead to consequences like pneumonia, sepsis, and necrosis (De Vos et al., 1997; Edwards-Jones et al., 2003; Mayhall, 2003). There is therefore a need for sensitive and specific P. aeruginosa detection tests in clinical laboratory for rapid triage and early aggressive targeted therapy.

Molecular diagnostics (MDx) has taken a prominent place and has shown advantages in the clinical diagnostic laboratory for routine detection, fingerprinting, and epidemiologic analysis of infectious microorganisms. Firstly, MDx minimizes the requirement for cultivation, which reduce the time required for morphology and biochemistry diagnosis. Disadvantages of cultivation include the selection of microbe-specific artificial media, the ability of the microbe to propagate on the selected media and long incubation period (Tang et al., 1997; Basu et al., 2015). Secondly, MDx may be used to detect microbes directly from clinical specimens. This reduces the exposure of infection agents and decreases the health risk for the laboratory personnel (Tang et al., 1997). Lastly, the quality and quantity of nucleic acids can be maintained for a prolonged period of time with appropriate storage temperature and specimen preservation (Tang et al., 1997; Leal-Klevezas et al., 2000). This review aims to discuss the advantages and limitations of some MDx techniques for P. aeruginosa detection to allow the rapid implementation of infection-control and intervention practices.

Detection and Identification of Pseudomonas aeruginosa

Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR)

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is one of the notable methods for the detection and identification of P. aeruginosa (Deschaght et al., 2011). This method applies primer mediated enzymatic amplification of DNA to synthesize new strand of DNA complementary to the targeted template strand. Different targeted genes have been employed to detect P. aeruginosa on clinical samples such as ecfX, oprL, and gyrB due to their high sensitivity and specificity (De Vos et al., 1997; Qin et al., 2003; Anuj et al., 2009). False-positive results (using 16S rRNA and oprI genes) and false negative results (using algD and toxA genes) have also been reported previously (Qin et al., 2003; Cattoir et al., 2010). This may due to the extensive genomic plasticity (Shen et al., 2006) and horizontal gene transfer of this bacterium to other Enterobacteriaceae species (Anuj et al., 2009). Furthermore, the comparative-genomics information and inter- or intra-species sequence polymorphisms within the target region are unknown (Qin et al., 2003). To improve aforementioned issues, multiplex-PCR using parallel testing of more than one targeted gene may be used. Multiplex-PCR is able to provide internal controls, lower the reagent costs, preserve precious samples and determine the quality and quantity of template more effectively (Edwards and Gibbs, 1994; Elnifro et al., 2000). The major drawback of this assay is primer designing. The primer–primer competition and relative abundance of target in regard to primer concentration need to be taken into consideration. To date, no standard protocol for the detection of P. aeruginosa using multiplex-PCR is available despite of the development and continuous improvement of this approach (De Vos et al., 1997; da Silva Filho et al., 2004; Anuj et al., 2009; Thong et al., 2011; Salman et al., 2013; Aghamollaei et al., 2015).

In recent decades, the advert of the quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) is gaining popularity for detection of pathogens in clinical microbiology (Klein, 2002; Mackay, 2004; Sails, 2004; Kaltenboeck and Wang, 2005; Valasek and Repa, 2005; Espy et al., 2006; Kubista, 2008; Bustin et al., 2009; Saeed and Ahmad, 2013). This technology only requires less than 5 h, is simple, reproducible, and improved quantitative capacity over conventional PCR (Fournier et al., 2013). Such a powerful tool could be applied for the detection of P. aeruginosa directly from sputum samples of CF patients, positive blood cultures, corneal samples, and chronic wounds. To simplify and standardize the experimental design, commercially distributed kits for the detection of P. aeruginosa are available in the market. Unfortunately, the instrument for qPCR is expensive for extra light sources and filters for fluorescence detection and may require high cost of maintenance.

Isothermal Amplification Methods

Current advancement in PCR has led to the development of isothermal amplification methods, including loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) and polymerase spiral reaction (PSR). The isothermal amplification method requires only basic inexpensive equipment (i.e., standard heat block) with minimal operator training (Diaz and Winchell, 2016) and is capable of providing reliable results within 1 h. This method is useful for clinical screening, especially under lack of resources or for point-of-care testing.

LAMP is a unique nucleic acid amplification technique that amplifies few copies of DNA into billion copies within an hour under isothermal conditions with greater specificity. In LAMP reaction, the gene was amplified when self-elongation of templates from the stem loop structure formed at the 3′-terminal plus the binding and elongation of new primers to the loop region (Notomi et al., 2000). In a previous study, the development and validation of LAMP assays for 426 clinical samples (including 252 P. aeruginosa and 174 non-P. aeruginosa isolates) were performed (Zhao et al., 2011). This study showed the detection limit of extracted DNA was 2.8 ng/μl, while sensitivity of LAMP and PCR assays was found to be 97.6% (246/252 P. aeruginosa isolates) and 90.5% (228/252 P. aeruginosa isolates), respectively; with a 100% specificity for both assay. Furthermore, LAMP enables direct detection of P. aeruginosa from clinical patient plasma within 20 min without the requirement for DNA purification (Yang et al., 2016). The disadvantages of LAMP are proper primer designing required and LAMP multiplexing approach is less developed compared to PCR. On the other hand, PSR is a nucleic acid amplification method based on the utilization of a DNA polymerase with strand displacement activity under isothermal conditions. In China, PSR was developed for rapid detection of P. aeruginosa by targeting toxA gene within 60 min without an initial denaturation step as required by LAMP. The detection limit of extracted DNA was 2.3 pg/μl and 10-fold more sensitive than conventional PCR, where the reaction proceeds as soon as the temperature reaches 61°C to 65°C (Dong et al., 2015).

Molecular Typing Methods of Pseudomonas aeruginosa

Pulsed-Field Gel Electrophoresis (PFGE)

Pulse-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) is for separation of large DNA molecules ranging from 10 kb to 10 Mb on a solid matrix by applying an electric field that periodically changes direction (Kaufmann, 1998). It is a popular method for large-scale epidemiological investigations due to its discriminatory powers (DIs) (Selim et al., 2015; Tang et al., 2017). The DIs expresses the homogeneity of distribution between types and valuable for defining the best typing strategy and interpreting data (Grundmann et al., 1995). The combination of PFGE and restriction endonuclease digestion from genomic DNA isolated from bacterial isolates has proved to be a useful epidemiological tool. For instance, PFGE-SpeI of P. aeruginosa was found to have extremely high DIs between 0.98 and 0.998 (Grundmann et al., 1995). Besides, PFGE is a relatively inexpensive approach with excellent typeability, high sensitivity (Abu-Taleb et al., 2013), intra-laboratory reproducibility and easy interpretation (Römling and Tümmler, 2000; Ballarini et al., 2012). PFGE-SpeI approach is the recommended method for P. aeruginosa genomes study (Morales et al., 2004; Libisch, 2013). Macrorestriction patterns generated by restriction enzyme SpeI showed 100% reproducibility and the typeability was in between 95 and 100% (Grundmann et al., 1995). One major drawback of PFGE for P. aeruginosa typing is the lack of standardized protocols, causing limited intra- and inter-laboratory reproducibility. As improvement, the development of standardized PFGE protocol (culture to gel image) is recommended. Another notable disadvantage of PFGE typing is its labor-intensive method which requires few days to obtain results and involves technical expertise to handle it.

Multiple Locus Variable-Number Tandem Repeat Analysis (MLVA)

Multiple locus variable-number tandem repeat analysis (MLVA) is a PCR-based method to subtype microbial strains on the analysis of variable copy numbers of tandem repeats (VNTR). MLVA utilizes the naturally occurring variation in the number of tandem repeated DNA sequences found in multiple loci or regions in a bacterial genome detected by PCR using flanking primers (Sabat et al., 2003; de Filippis and McKee, 2012; Sobral et al., 2012). MLVA is more favorable as it appears to contain greater diversity and, hence, greater discriminatory capacity when compared to other type of molecular typing system (Keim et al., 2000). The MLVA scheme for P. aeruginosa was first developed by Onteniente et al. (2003) and was subsequently improved by adding new epidemiologically information markers (de Filippis and McKee, 2012). It is a promising tool for molecular surveillance of P. aeruginosa in the public health as it is highly reproducible, easy to use and interpret (Onteniente et al., 2003; de Filippis and McKee, 2012; Maâtallah et al., 2013). Besides, MLVA is also a rapid approach with high resolution, thus is beneficial for resolving large and complex outbreak situations. This method is also suitable to apply on commercial kits and large-scale automated platforms (e.g., pipetting robots and automated sequencers) which are already available at the markets (Llanes et al., 2013). Almost 100 isolates could be genotyped in less than 4 days, starting from bacterial colonies using the genotyping kit TYPPSEUDO ceeramTools® (Ceeram, La Chapelle-sur-Erdre, France) and automated capillary-based MLVA system (Sobral et al., 2012). A potential drawback of MLVA method is that inter-laboratory comparison studies cannot be conducted directly. This is mainly due to the fact that the generated amplicons are monitored as banding patterns by conventional electrophoresis on agarose gels, causing difficulty to determine which band in a pattern corresponds to which PCR target. Besides, this approach is also high assay-specific for different organisms and lacks standardization for the majority of published assays (Sabat et al., 2013).

Multilocus Sequencing Typing (MLST)

Multilocus sequencing typing (MLST) analysis is an electronically portable, universal, and definitive bacterial typing method that focuses solely on conserved housekeeping genes and the combination of each allele (Wendt and Heo, 2016). This is aim to define the sequence type for each isolate and provide information in the relatedness of bacterial isolates at the core genome level. This method has become a very well-known (or popular) tool for molecular evolution studies of pathogens and global epidemiological studies. MLST scheme has been first developed for P. aeruginosa by Curran et al. (2004). The study revealed that P. aeruginosa is best described as non-clonal but has highly successful epidemic clones or clonal complexes population (Curran et al., 2004). One of the great advantages of MLST is the accessibility of online-based MLST reference databases, allowing this method to gain widespread popularity as an epidemiological tool for bacterial typing. Currently, the MLST databases can be open accessed at http://pubmlst.org/databases and http://www.mlst.net/databases/. The standardization of MLST data allows users to investigate the molecular evolution of pathogens over time in different geographic regions. For outbreaks surveillance and management, MLST being able to rapidly keep track of infectious diseases is of paramount importance (Chui and Li, 2015). MLST is also a technically straightforward typing tool and provides unambiguous data that is highly reproducible between laboratories (Pérez-Losada et al., 2011). Unfortunately, the great disadvantage of MLST is its high cost and insufficiently discerning for routine use in local surveillance and outbreaks. Additionally, the MLST depends on housekeeping genes which are relatively conserved to establish genetic relatedness between isolates as it may lack the discriminatory power to differentiate certain bacteria (Noller et al., 2003; Pérez-Losada et al., 2011).

DiversiLab Repetitive-Sequence-Based PCR (DL rep-PCR)

DiversiLab (DL), an automated repetitive-sequence-based PCR (rep-PCR) bacterial typing system (bioMérieux), comes with a high level of standardization, particularly at the electrophoresis step by using the Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Inc., Santa Clara, CA, United States) (Healy et al., 2005; Deplano et al., 2011). In comparison to traditional gel electrophoresis, DL system makes use of microfluidic capillary electrophoresis to overcome the low reproducibility of the previous rep-PCR approaches (Sabat et al., 2013). Besides, DL system also provides a user-friendly internet-based computer-assisted data analysis (Fluit et al., 2010; Brossier et al., 2015). The reliability of the data obtained from the system is species dependent. Hence, a validation for each bacterial species is necessary prior to its use in a routine clinical laboratory (Harrington et al., 2007; Doleans-Jordheim et al., 2009). Another major drawback of DL system for P. aeruginosa is the lack of a suitable cutoff values from the manufacturer. The classification of the closely related DL rep-PCR profiles as identical genotypes may be influenced by the number of different fragments obtained due to deletions, insertions, inversion of DNA, or mutation of the restriction. For outbreaks or routine clinical laboratory bacterial typing practices, the high cost of reagents and kits as well as the necessity to use different fingerprint kits for each bacterial species are among the disadvantages of DL system which need to be overcome. Moreover, the initial instrument installation and maintenance costs also need to be taken into consideration.

The New Era of Molecular Diagnostics: Next Generation Sequencing (Ngs) Technology

Over the years, next generation sequencing (NGS) technology has gradually been replacing the first generation sequencing, the Sanger sequencing (Sboner et al., 2011; Muir et al., 2016). The NGS technology is evolving into a molecular microscope, which manages to provide a broad investigations of the bacterial genomes (e.g., transcription, translation, replication, methylation, and nuclear DNA folding) and are readily applied in clinical microbiology to replace conventional characterization studies of pathogens (Didelot et al., 2012; Gargis et al., 2012, 2016; Behjati and Tarpey, 2013; Deurenberg et al., 2017; Tagini and Greub, 2017).

Since first introduced to the market in 2005, NGS is widely accepted, allowing decentralized laboratories to conduct their own internal genome sequencing projects at a lower cost (Quail et al., 2012; Liao et al., 2015). Besides, NGS also relatively requires less amount of DNA to produce accurate and reliable data. This technology has greater advantages in producing high quality, robustness and lower noise background sequence data. Unfortunately, a successful NGS project requires expertise to perform the wet lab, analyze, and interpret the data (Buermans and den Dunnen, 2014; Ari and Arikan, 2016). In addition, users need to face technical challenges where the current available computational infrastructures and software need to be upgraded in order to store and analyze large bioinformatics datasets. This will be a constant challenge for users as sequencing technology continues to evolve and develop new computational strategies (Tang et al., 2017).

NGS Applications of Clinical Pseudomonas aeruginosa

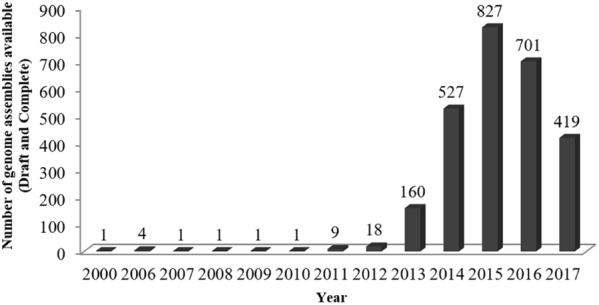

The applications of NGS for clinical P. aeruginosa are wide-ranging and include 16S rRNA gene sequence, whole genome sequencing (WGS), transcriptome profiling, exome sequencing, virtual resistance testing, and public health surveillance. This eventually increases the number of publicly available P. aeruginosa genomes (Figure 1). Hitherto, there are a total of 2678 assembled genomes deposited in NCBI database1 and among them 106 are completed genomes (retrieved in January, 2018). Knowledge on the bacterial genomes helps to harbor information about the genomes evolution, niche adaptation, infectious potential (Bowlin et al., 2014; Dubern et al., 2015; Bartell et al., 2017) and the molecular basis of antimicrobial resistance (Ramanathan et al., 2017; Sherrard et al., 2017). Throughout the years, this technology has facilitated to reveal the pathogenesis of this bacterium. For examples, it is opined that NGS can be used not only to study the bacteria genome, but it can also be used to study the antimicrobial resistance (Chan, 2016). Also, the studies by Kos et al. (2015) and Ramanathan et al. (2017) demonstrated the utility of NGS to define relevant resistance elements as well as highlight the diversity of resistance determinants within P. aeruginosa. This information is especially valuable for diagnostics, therapeutics, and preventions of P. aeruginosa infections.

FIGURE 1.

Number of Pseudomonas aeruginosa genomes available in NCBI database from year 2000 to 2017.

Studies on the bacterial genomes also can provide information about the relationship of different pathogens which can be used as source tracking during infection outbreaks. In recent years, NGS coupled with WGS can be used for source tracking of P. aeruginosa in a hospital setting, and that acquisitions can be traced to a specific source within a hospital ward (Quick et al., 2014). Besides, WGS could also be applied for epidemiological investigation of P. aeruginosa in intensive care units (ICU) (Blanc et al., 2016). Recent years, NGS has been adapted for 16S rRNA gene based metagenomics study to rapidly catalog the bacterial species in mixed clinical specimens, without need for prior culture (Lim et al., 2014). Cummings et al. (2016) demonstrated that NGS 16S rRNA gene sequencing has generated a reproducible, analytically sensitive, and accurate assessment of the identity and relative abundance of organisms present in polymicrobial samples, outperforming standard culture.

Conclusion

Over the last decades, several molecular methods have been developed for genotypically detecting and identifying pathogens in clinical diagnostic laboratories. All the methods discussed here have both advantages and drawbacks or rather limitations(Table 1). Another trend for microbial identification which relies on microbial physiological or biochemical characteristics including antibiotic-resistance has been fast developed from well-established analytical profile index (API) to mass spectrometry (MS)-based methodologies. Nevertheless, the enrichment of bacterial cells and metabolites for detection and lack of biomarker database are still the major challenges (Cheng et al., 2016). Coupling with genetic and non-genetic methods have also been developed such as PCR-MS for determining nucleotide compositions of strain-specific PCR products (Ecker et al., 2005). Further studies of both genotypic and phenotypic methodologies will certainly facilitate the development of perfect diagnostic, which is rapid, specific, sensitive, easy to perform and interpret, cost-effective, and high-throughput.

Table 1.

Comparison table of selected molecular techniques.

| Molecular techniques | Advantages | Limitations | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| PCR | ∙ High sensitivity ∙ High specificity | ∙ False-positive results ∙ Negative results | Qin et al., 2003; Cattoir et al., 2010 |

| Multiplex PCR | ∙ Provide internal controls ∙ Low reagent costs ∙ Able to preserve precious samples ∙ Able to determine the quality and quantity of template more effectively | ∙ Primer designing ∙ No standard protocol | De Vos et al., 1997; da Silva Filho et al., 2004; Anuj et al., 2009; Thong et al., 2011; Salman et al., 2013; Aghamollaei et al., 2015 |

| qPCR | ∙ Reproducible methods (less than 5 h) ∙ Direct detection from sputum samples ∙ Availability of commercial kits in the market | ∙ Expensive instrument ∙ High cost of maintenance | Deschaght et al., 2009; Cattoir et al., 2010; Clifford et al., 2012; Carlesse et al., 2016 |

| LAMP | ∙ Low detection limit with high sensitivity ∙ Rapid detection (∼20 min) without DNA purification ∙ Only required basic inexpensive equipment with minimal operator training | ∙ Primer designing ∙ Less develop multiplexing approach | Zhao et al., 2011 |

| PSR | ∙ Low detection limit with high sensitivity ∙ Rapid detection (∼60 min) without an initial denaturation ∙ Only required basic inexpensive equipment with minimal operator training | ∙ Still in the progress on method development | Dong et al., 2015 |

| PFGE | ∙ Inexpensive ∙ Excellent typeability ∙ High sensitivity ∙ Easy interpretation | ∙ Lack of standardized protocols ∙ Limited reproducibility ∙ Labor-intensive method ∙ Technical expertise required | Grundmann et al., 1995; Morales et al., 2004; Libisch, 2013 |

| MLVA | ∙ Highly reproducible and easy interpretation ∙ Rapid approach with high resolution ∙ Suitable for large-scale automated platforms | ∙ Assay-specific for different organisms ∙ Lacks standardization of assay | Onteniente et al., 2003; Sobral et al., 2012; Maâtallah et al., 2013 |

| MLST | ∙ Accessibility of online-based MLST reference databases ∙ Standardization of MLST data ∙ Highly reproducible | ∙ High cost ∙ Insufficiently discerning for routine use in local surveillance and outbreaks ∙ Lack the discriminatory power to differentiate certain bacteria | Curran et al., 2004 |

| DL rep-PCR | ∙ Standardization of assay ∙ Improved reproducibility ∙ User-friendly internet-based computer-assisted data analysis | ∙ Validation for each bacterial species is necessary ∙ Lack of a suitable cutoff values from the manufacturer ∙ High cost of reagents and kits ∙ Necessity to use different fingerprint kits for each bacterial species ∙ High instrument installation and maintenance costs | Fluit et al., 2010; Deplano et al., 2011; Brossier et al., 2015 |

| NGS | ∙ Requires less amount of DNA ∙ High quality, robustness and lower noise background sequence data ∙ Reproducible ∙ Analytically sensitive, and accurate assessment of the identity and relative abundance of organisms present in polymicrobial samples | ∙ Technical expertise required to perform the wet lab, analyze, and interpret the data ∙ Computational infrastructures and software need to be upgraded in order to store and analyze large bioinformatics datasets | Quick et al., 2014; Blanc et al., 2016 |

PCR, polymerase chain reaction; qPCR, quantitative real-time PCR, LAMP, loop-mediated isothermal amplification; PSR, polymerase spiral reaction; PFGE, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis; MLVA, multiple locus variable-number tandem repeat analysis; MLST, multilocus sequencing typing; DL rep-PCR, DiversiLab repetitive-sequence-based PCR; NGS, next generation sequencing.

Author Contributions

J-WC and YYL contributed to data collection, analysis, and draft the manuscript. TK, K-GC, and C-YC revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Funding. The work in C-YC lab is supported by University of Bradford. K-GC thanks the financial support from JBK (Grant Nos. GA001-2016 and GA002-2016) and PPP grant from UM (Grant No. PG135-2016A).

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

References

- Abu-Taleb M. A., Mohamed A. E. E. S., El-Eslam H. N. (2013). Application of pulsed field gel electrophoresis and ribotyping as genotypic methods versus phenotypic methods for typing of nosocomial infections caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from surgical wards in Suez Canal University hospital. Egypt. J. Med. Microbiol. 22 83–99. 10.12816/0004945 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aghamollaei H., Moghaddam M. M., Kooshki H., Heiat M., Mirnejad R., Barzi N. S. (2015). Detection of Pseudomonas aeruginosa by a triplex polymerase chain reaction assay based on lasI/R and gyrB genes. J. Infect. Public Health 8 314–322. 10.1016/j.jiph.2015.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anuj S. N., Whiley D. M., Kidd T. J., Bell S. C., Wainwright C. E., Nissen M. D., et al. (2009). Identification of Pseudomonas aeruginosa by a duplex real-time polymerase chain reaction assay targeting the ecfX and the gyrB genes. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 63 127–131. 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2008.09.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ari, Ş, Arikan M. (2016). “Next-generation sequencing: advantages, disadvantages, and future,” in Plant Omics: Trends and Applications, eds K. R. Hakeem, Tombulo H., Tombuloğlu G. (Cham: Springer; ), 109–135. [Google Scholar]

- Ballarini A., Scalet G., Kos M., Cramer N., Wiehlmann L., Jousson O. (2012). Molecular typing and epidemiological investigation of clinical populations of Pseudomonas aeruginosa using an oligonucleotide-microarray. BMC Microbiol. 12:152. 10.1186/1471-2180-12-152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartell J. A., Blazier A. S., Yen P., Thøgersen J. C., Jelsbak L., Goldberg J. B., et al. (2017). Reconstruction of the metabolic network of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to interrogate virulence factor synthesis. Nat. Commun. 8:14631. 10.1038/ncomms14631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu S., Bose C., Ojha N., Das N., Das J., Pal M., et al. (2015). Evolution of bacterial and fungal growth media. Bioinformation 11 182–184. 10.6026/97320630011182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behjati S., Tarpey P. S. (2013). What is next generation sequencing? Arch. Dis. Child. Educ. Pract. Ed. 98 236–238. 10.1136/archdischild-2013-304340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanc D. S., Gomes Magalhaes B., Abdelbary M., Prod’hom G., Greub G., Wasserfallen J. B., et al. (2016). Hand soap contamination by Pseudomonas aeruginosa in a tertiary care hospital: no evidence of impact on patients. J. Hosp. Infect. 93 63–67. 10.1016/j.jhin.2016.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlin N. O., Williams J. D., Knoten C. A., Torhan M. C., Tashjian T. F., Li B., et al. (2014). Mutations in the Pseudomonas aeruginosa needle protein gene pscF confer resistance to phenoxyacetamide inhibitors of the type III secretion system. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 58 2211–2220. 10.1128/AAC.02795-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brossier F., Micaelo M., Luyt C. E., Lu Q., Chastre J., Arbelot C., et al. (2015). Could the DiversiLab(R) semi-automated repetitive-sequence-based PCR be an acceptable technique for typing isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa? An answer from our experience and a review of the literature. Can. J. Microbiol. 61 903–912. 10.1139/cjm-2015-0372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buermans H. P., den Dunnen J. T. (2014). Next generation sequencing technology: advances and applications. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1842 1932–1941. 10.1016/j.bbadis.2014.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bustin S. A., Benes V., Garson J. A., Hellemans J., Huggett J., Kubista M., et al. (2009). The MIQE guidelines: minimum information for publication of quantitative real-time PCR experiments. Clin. Chem. 55 611–622. 10.1373/clinchem.2008.112797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlesse F., Cappellano P., Quiles M. G., Menezes L. C., Petrilli A. S., Pignatari A. C. (2016). Clinical relevance of molecular identification of microorganisms and detection of antimicrobial resistance genes in bloodstream infections of paediatric cancer patients. BMC Infect. Dis. 16:462. 10.1186/s12879-016-1792-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cattoir V., Gilibert A., Le Glaunec J.-M., Launay N., Bait-Mérabet L., Legrand P. (2010). Rapid detection of Pseudomonas aeruginosa from positive blood cultures by quantitative PCR. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 9:21. 10.1186/1476-0711-9-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan K. G. (2016). Whole-genome sequencing in the prediction of antimicrobial resistance. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 14 617–619. 10.1080/14787210.2016.1193005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng K., Chui H., Domish L., Hernandez D., Wang G. (2016). Recent development of mass spectrometry and proteomics applications in identification and typing of bacteria. Proteomics Clin. Appl. 10 346–357. 10.1002/prca.201500086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chui L., Li V. (2015). “Chapter 8 - Technical and software advances in bacterial pathogen typing,” in Methods in Microbiology, eds A. Sails, Y.-W. Tang. (New York, NY: Academic Press; ), 289–327. [Google Scholar]

- Clifford R. J., Milillo M., Prestwood J., Quintero R., Zurawski D. V., Kwak Y. I., et al. (2012). Detection of bacterial 16S rRNA and identification of four clinically important bacteria by real-time PCR. PLoS One 7:e48558. 10.1371/journal.pone.0048558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings L. A., Kurosawa K., Hoogestraat D. R., SenGupta D. J., Candra F., Doyle M., et al. (2016). Clinical next generation sequencing outperforms standard microbiological culture for characterizing polymicrobial samples. Clin. Chem. 62 1465–1473. 10.1373/clinchem.2016.258806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran B., Jonas D., Grundmann H., Pitt T., Dowson C. G. (2004). Development of a multilocus sequence typing scheme for the opportunistic pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42 5644–5649. 10.1128/JCM.42.12.5644-5649.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva Filho L. V., Tateno A. F., Velloso Lde F., Levi J. E., Fernandes S., et al. (2004). Identification of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Burkholderia cepacia complex, and Stenotrophomonas maltophilia in respiratory samples from cystic fibrosis patients using multiplex PCR. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 37 537–547. 10.1002/ppul.20016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Filippis I., McKee M. L. (2012). Molecular Typing in Bacterial Infections. New York, NY: Humana Press. [Google Scholar]

- De Vos D., Lim A., Pirnay J.-P., Struelens M., Vandenvelde C., Duinslaeger L., et al. (1997). Direct detection and identification of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in clinical samples such as skin biopsy specimens and expectorations by multiplex PCR based on two outer membrane lipoprotein genes, oprI and oprL. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35 1295–1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deplano A., Denis O., Rodriguez-Villalobos H., De Ryck R., Struelens M. J., Hallin M. (2011). Controlled performance evaluation of the DiversiLab repetitive-sequence-based genotyping system for typing multidrug-resistant health care-associated bacterial pathogens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 49 3616–3620. 10.1128/JCM.00528-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deschaght P., De Baere T., Van Simaey L., De Baets F., De Vos D., et al. (2009). Comparison of the sensitivity of culture, PCR and quantitative real-time PCR for the detection of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in sputum of cystic fibrosis patients. BMC Microbiol. 9:244. 10.1186/1471-2180-9-244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deschaght P., De Baets F., Vaneechoutte M. (2011). PCR and the detection of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in respiratory samples of CF patients. A literature review. J. Cyst. Fibros. 10 293–297. 10.1016/j.jcf.2011.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deurenberg R. H., Bathoorn E., Chlebowicz M. A., Couto N., Ferdous M., García-Cobos S., et al. (2017). Application of next generation sequencing in clinical microbiology and infection prevention. J. Biotechnol. 243 16–24. 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2016.12.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz M. H., Winchell J. M. (2016). The evolution of advanced molecular diagnostics for the detection and characterization of Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Front. Microbiol. 7:232. 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Didelot X., Bowden R., Wilson D. J., Peto T. E., Crook D. W. (2012). Transforming clinical microbiology with bacterial genome sequencing. Nat. Rev. Genet. 13 601–612. 10.1038/nrg3226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doleans-Jordheim A., Cournoyer B., Bergeron E., Croize J., Salord H., Andre J., et al. (2009). Reliability of Pseudomonas aeruginosa semi-automated rep-PCR genotyping in various epidemiological situations. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 28 1105–1111. 10.1007/s10096-009-0755-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong D., Zou D., Liu H., Yang Z., Huang S., Liu N., et al. (2015). Rapid detection of Pseudomonas aeruginosa targeting the toxA gene in intensive care unit patients from Beijing, China. Front. Microbiol. 6:1100. 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douraghi M., Ghasemi F., Dallal M. M., Rahbar M., Rahimiforoushani A. (2014). Molecular identification of Pseudomonas aeruginosa recovered from cystic fibrosis patients. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 55 50–53. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubern J. F., Cigana C., De Simone M., Lazenby J., Juhas M., Schwager S., et al. (2015). Integrated whole genome screening for Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence genes using multiple disease models reveals that pathogenicity is host specific. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 17 4379–4393. 10.1111/1462-2920.12863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ecker D. J., Sampath R., Blyn L. B., Eshoo M. W., Ivy C., Ecker J. A., et al. (2005). Rapid identification and strain-typing of respiratory pathogens for epidemic surveillance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102 8012–8017. 10.1073/pnas.0409920102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards M. C., Gibbs R. A. (1994). Multiplex PCR: advantages, development, and applications. Genome Res. 3 S65–S75. 10.1101/gr.3.4.S65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards-Jones V., Greenwood J. E. and On behalf of the Manchester Burns Research Group (2003). What’s new in burn microbiology?: James Laing memorial prize essay 2000. Burns 29 15–24. 10.1016/S0305-4179(02)00203-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elnifro E. M., Ashshi A. M., Cooper R. J., Klapper P. E. (2000). Multiplex PCR: optimization and application in diagnostic virology. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 13 559–570. 10.1128/CMR.13.4.559-570.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espy M., Uhl J., Sloan L., Buckwalter S., Jones M., Vetter E., et al. (2006). Real-time PCR in clinical microbiology: applications for routine laboratory testing. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 19 165–256. 10.1128/CMR.19.1.165-256.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fluit A. C., Terlingen A. M., Andriessen L., Ikawaty R., van Mansfeld R., Top J., et al. (2010). Evaluation of the DiversiLab system for detection of hospital outbreaks of infections by different bacterial species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 48 3979–3989. 10.1128/jcm.01191-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fournier P.-E., Drancourt M., Colson P., Rolain J.-M., La Scola B., Raoult D. (2013). Modern clinical microbiology: new challenges and solutions. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 11 574–585. 10.1038/nrmicro3068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gargis A. S., Kalman L., Berry M. W., Bick D. P., Dimmock D. P., Hambuch T., et al. (2012). Assuring the quality of next-generation sequencing in clinical laboratory practice. Nat. Biotechnol. 30 1033–1036. 10.1038/nbt.2403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gargis A. S., Kalman L., Lubin I. M. (2016). Assuring the quality of next-generation sequencing in clinical microbiology and public health laboratories. J. Clin. Microbiol. 54 2857–2865. 10.1128/JCM.00949-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundmann H., Schneider C., Hartung D., Daschner F. D., Pitt T. L. (1995). Discriminatory power of three DNA-based typing techniques for Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33 528–534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington S. M., Stock F., Kominski A., Campbell J., Hormazabal J., Livio S., et al. (2007). Genotypic analysis of invasive Streptococcus pneumoniae from Mali, Africa, by semiautomated repetitive-element PCR and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45 707–714. 10.1128/JCM.01871-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Healy M., Huong J., Bittner T., Lising M., Frye S., Raza S., et al. (2005). Microbial DNA typing by automated repetitive-sequence-based PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43 199–207. 10.1128/jcm.43.1.199-207.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaltenboeck B., Wang C. (2005). Advances in real-time PCR: application to clinical laboratory diagnostics. Adv. Clin. Chem. 40 219–259. 10.1016/S0065-2423(05)40006-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann M. E. (1998). “Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis,” in Molecular Bacteriology: Protocols and Clinical Applications, eds Woodford N., Johnson A. P. (Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; ), 33–50. [Google Scholar]

- Keim P., Price L. B., Klevytska A. M., Smith K. L., Schupp J. M., Okinaka R., et al. (2000). Multiple-locus variable-number tandem repeat analysis reveals genetic relationships within Bacillus anthracis. J. Bacteriol. 182 2928–2936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein D. (2002). Quantification using real-time PCR technology: applications and limitations. Trends Mol. Med. 8 257–260. 10.1016/S1471-4914(02)02355-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kos V. N., Déraspe M., McLaughlin R. E., Whiteaker J. D., Roy P. H., Alm R. A., et al. (2015). The resistome of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in relationship to phenotypic susceptibility. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 59 427–436. 10.1128/AAC.03954-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubista M. (2008). Emerging real-time PCR application. Drug Discov. World 9 57–66. [Google Scholar]

- Leal-Klevezas D. S., Martìnez-Vázquez I. O., Cuevas-Hernández B., Martìnez-Soriano J. P. (2000). Antifreeze solution improves DNA recovery by preserving the integrity of pathogen-infected blood and other tissues. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 7 945–946. 10.1128/CDLI.7.6.945-946.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao Y.-C., Lin S.-H., Lin H.-H. (2015). Completing bacterial genome assemblies: strategy and performance comparisons. Sci. Rep. 5:8747. 10.1038/srep08747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libisch B. (2013). “Molecular typing methods for the genus Pseudomonas,” in Molecular Typing in Bacterial Infections, eds Filippis I. de, McKee M. L. (Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; ), 407–429. 10.1007/978-1-62703-185-1_24 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lim Y. W., Evangelista J. S. III, Schmieder R., Bailey B., Haynes M., Furlan M., et al. (2014). Clinical insights from metagenomic analysis of sputum samples from patients with cystic fibrosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 52 425–437. 10.1128/jcm.02204-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llanes C., Pourcel C., Richardot C., Plésiat P., Fichant G., Cavallo J.-D., et al. (2013). Diversity of β-lactam resistance mechanisms in cystic fibrosis isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: a French multicentre study. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 68 1763–1771. 10.1093/jac/dkt115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maâtallah M., Bakhrouf A., Habeeb M. A., Turlej-Rogacka A., Iversen A., Pourcel C., et al. (2013). Four genotyping schemes for phylogenetic analysis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: comparison of their congruence with multi-locus sequence typing. PLoS One 8:e82069. 10.1371/journal.pone.0082069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackay I. M. (2004). Real-time PCR in the microbiology laboratory. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 10 190–212. 10.1111/j.1198-743X.2004.00722.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayhall C. G. (2003). The epidemiology of burn wound infections: then and now. Clin. Infect. Dis. 543–550. 10.1086/376993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales G., Wiehlmann L., Gudowius P., van Delden C., Tümmler B., Martínez J. L., et al. (2004). Structure of Pseudomonas aeruginosa populations analyzed by single nucleotide polymorphism and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis genotyping. J. Bacteriol. 186 4228–4237. 10.1128/JB.186.13.4228-4237.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muir P., Li S., Lou S., Wang D., Spakowicz D. J., Salichos L., et al. (2016). The real cost of sequencing: scaling computation to keep pace with data generation. Genome Biol. 17:53. 10.1186/s13059-016-0917-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noller A. C., McEllistrem M. C., Stine O. C., Morris J. G., Jr., Boxrud D. J., et al. (2003). Multilocus sequence typing reveals a lack of diversity among Escherichia coli O157:H7 isolates that are distinct by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41 675–679. 10.1128/JCM.41.2.675-679.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Notomi T., Okayama H., Masubuchi H., Yonekawa T., Watanabe K., Amino N., et al. (2000). Loop-mediated isothermal amplification of DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 28:E63 10.1093/nar/28.12.e63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onteniente L., Brisse S., Tassios P. T., Vergnaud G. (2003). Evaluation of the polymorphisms associated with tandem repeats for Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41 4991–4997. 10.1128/JCM.41.11.4991-4997.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Losada M., Porter M. L., Viscidi R. P., Crandall K. A. (2011). “Multilocus sequence typing of pathogens,” in Genetics and Evolution of Infectious Disease, ed. M. Tibayrenc. (London: Elsevier; ), 503–521. 10.1016/B978-0-12-384890-1.00017-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qin X., Emerson J., Stapp J., Stapp L., Abe P., Burns J. L. (2003). Use of real-time PCR with multiple targets to identify Pseudomonas aeruginosa and other nonfermenting gram-negative bacilli from patients with cystic fibrosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41 4312–4317. 10.1128/JCM.41.9.4312-4317.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quail M. A., Smith M., Coupland P., Otto T. D., Harris S. R., Connor T. R., et al. (2012). A tale of three next generation sequencing platforms: comparison of Ion Torrent, Pacific Biosciences and Illumina MiSeq sequencers. BMC Genomics 13:341. 10.1186/1471-2164-13-341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quick J., Cumley N., Wearn C. M., Niebel M., Constantinidou C., Thomas C. M., et al. (2014). Seeking the source of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections in a recently opened hospital: an observational study using whole-genome sequencing. BMJ Open 4:e006278. 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramanathan B., Jindal H. M., Le C. F., Gudimella R., Anwar A., Razali R., et al. (2017). Next generation sequencing reveals the antibiotic resistant variants in the genome of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. PLoS One 12:e0182524. 10.1371/journal.pone.0182524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice L. B. (2008). Federal funding for the study of antimicrobial resistance in nosocomial pathogens: no ESKAPE. J. Infect. Dis. 197 1079–1081. 10.1086/533452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Römling U., Tümmler B. (2000). Achieving 100% typeability of Pseudomonas aeruginosa by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38 464–465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabat A., Krzyszton-Russjan J., Strzalka W., Filipek R., Kosowska K., Hryniewicz W., et al. (2003). New method for typing Staphylococcus aureus strains: multiple-locus variable-number tandem repeat analysis of polymorphism and genetic relationships of clinical isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41 1801–1804. 10.1128/JCM.41.4.1801-1804.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabat A. J., Budimir A., Nashev D., Sa-Leao R., van Dijl J., Laurent F., et al. (2013). Overview of molecular typing methods for outbreak detection and epidemiological surveillance. Euro. Surveill. 18:20380 10.2807/ese.18.04.20380-en [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saeed K., Ahmad N. (2013). Real-time polymerase chain reaction: applications in diagnostic microbiology. Int. J. Med. Stud. 1 28–36. [Google Scholar]

- Sails A. D. (2004). “Applications of real-time PCR in clinical microbiology,” in Real-Time PCR: An Essential Guide, eds K. Edwards, Logan J., Saunders N. (Norfolk: Horizon Bioscience; ), 247–326. [Google Scholar]

- Salman M., Ali A., Haque A. (2013). A novel multiplex PCR for detection of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: a major cause of wound infections. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 29 957–961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sboner A., Mu X. J., Greenbaum D., Auerbach R. K., Gerstein M. B. (2011). The real cost of sequencing: higher than you think! Genome Biol. 12:125. 10.1186/gb-2011-12-8-125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selim S., El Kholy I., Hagagy N., El Alfay S., Aziz M. A. (2015). Rapid identification of Pseudomonas aeruginosa by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 29 152–156. 10.1080/13102818.2014.981065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen K., Sayeed S., Antalis P., Gladitz J., Ahmed A., Dice B., et al. (2006). Extensive genomic plasticity in Pseudomonas aeruginosa revealed by identification and distribution studies of novel genes among clinical isolates. Infect. Immun. 74 5272–5283. 10.1128/IAI.00546-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherrard L. J., Tai A. S., Wee B. A., Ramsay K. A., Kidd T. J., Ben Zakour N. L., et al. (2017). Within-host whole genome analysis of an antibiotic resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain sub-type in cystic fibrosis. PLoS One 12:e0172179. 10.1371/journal.pone.0172179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobral D., Mariani-Kurkdjian P., Bingen E., Vu-Thien H., Hormigos K., Lebeau B., et al. (2012). A new highly discriminatory multiplex capillary-based MLVA assay as a tool for the epidemiological survey of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis patients. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 31 2247–2256. 10.1007/s10096-012-1562-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starner T. D., McCray P. B. (2005). Pathogenesis of early lung disease in cystic fibrosis: a window of opportunity to eradicate bacteria. Ann. Intern. Med. 143 816–822. 10.7326/0003-4819-143-11-200512060-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tagini F., Greub G. (2017). Bacterial genome sequencing in clinical microbiology: a pathogen-oriented review. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 36 2007–2020. 10.1007/s10096-017-3024-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang P., Croxen M. A., Hasan M. R., Hsiao W. W., Hoang L. M. (2017). Infection control in the new age of genomic epidemiology. Am. J. Infect. Control 45 170–179. 10.1016/j.ajic.2016.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Y.-W., Procop G. W., Persing D. H. (1997). Molecular diagnostics of infectious diseases. Clin. Chem. 43 2021–2038. 10.1097/MOP.0b013e328320d87e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thong K., Lai M., Teh C., Chua K. (2011). Simultaneous detection of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Acinetobacter baumannii, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa by multiplex PCR. Trop. Biomed. 28 21–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valasek M. A., Repa J. J. (2005). The power of real-time PCR. Adv. Physiol. Educ. 29 151–159. 10.1152/advan.00019.2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendt M., Heo G.-J. (2016). Multilocus sequence typing analysis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from pet Chinese stripe-necked turtles (Ocadia sinensis). Lab. Anim. Res. 32 208–216. 10.5625/lar.2016.32.4.208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization [WHO] (2017). Global Priority List of Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria to Guide Research, Discovery, and Development of New Antibiotics. Geneva: WHO. [Google Scholar]

- Yang R., Fu S., Ye L., Gong M., Yang J., Fan Y., et al. (2016). Rapid detection of Pseudomonas aeruginosa septicemia by real-time fluorescence loop-mediated isothermal amplification of free DNA in blood samples. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 9 13701–13711. 10.1371/journal.pone.0013733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X., Wang L., Li Y., Xu Z., Li L., He X., et al. (2011). Development and application of a loop-mediated isothermal amplification method on rapid detection of Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 27 181–184. 10.1016/j.foodres.2011.04.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]