Abstract

Sequence analysis of the coding regions and splice site sequences in inherited retinal diseases is not able to uncover ∼40% of the causal variants. Whole-genome sequencing can identify most of the non-coding variants, but their interpretation is still very challenging, in particular when the relevant gene is expressed in a tissue-specific manner. Deep-intronic variants in ABCA4 have been associated with autosomal-recessive Stargardt disease (STGD1), but the exact pathogenic mechanism is unknown. By generating photoreceptor precursor cells (PPCs) from fibroblasts obtained from individuals with STGD1, we demonstrated that two neighboring deep-intronic ABCA4 variants (c.4539+2001G>A and c.4539+2028C>T) result in a retina-specific 345-nt pseudoexon insertion (predicted protein change: p.Arg1514Leufs∗36), likely due to the creation of exonic enhancers. Administration of antisense oligonucleotides (AONs) targeting the 345-nt pseudoexon can significantly rescue the splicing defect observed in PPCs of two individuals with these mutations. Intriguingly, an AON that is complementary to c.4539+2001G>A rescued the splicing defect only in PPCs derived from an individual with STGD1 with this but not the other mutation, demonstrating the high specificity of AONs. In addition, a single AON molecule rescued splicing defects associated with different neighboring mutations, thereby providing new strategies for the treatment of persons with STGD1. As many genes associated with human genetic conditions are expressed in specific tissues and pre-mRNA splicing may also rely on organ-specific factors, our approach to investigate and treat splicing variants using differentiated cells derived from individuals with STGD1 can be applied to any tissue of interest.

Keywords: Stargardt disease, ABCA4, deep-intronic mutation, pseudoexon, splicing modulation, induced pluripotent stem cells, photoreceptor precursor cells, exonic splicing enhancer, antisense oligonucleotide, nonsense-mediated decay

Introduction

Stargardt disease (STGD1 [MIM: 248200]) is an autosomal-recessive retinal disorder characterized by a predominantly juvenile-onset macular dystrophy associated with central visual impairment and progressive bilateral atrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium. The accumulation of lipofuscin deposits around the macula or in the posterior pole of the retina is one of the hallmarks of STGD1.1, 2 STGD1 is caused by variants in ABCA4 that encodes the ATP-binding cassette transporter type A4 (ABCA4 [MIM: 601691]), a transmembrane protein localized at the rims of the photoreceptor disks that transports vitamin A derivatives in the visual cycle.3, 4, 5 Besides STGD1, variants in ABCA4 can also lead to other subtypes of retinal disease ranging from bull’s eye maculopathy to autosomal-recessive cone-rod dystrophy (arCRD [MIM: 604116])6, 7 and pan-retinal dystrophies,6, 8, 9, 10 depending on the severity of the alleles.

Biallelic ABCA4 variants can be identified in approximately 80% of the case subjects with STGD13, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18 and 30% of case subjects with arCRD,7 after sequencing coding regions and flanking splice sites. In general, individuals with arCRD or pan-retinal dystrophy carry two severe ABCA4 alleles, whereas individuals with STGD1 carry two moderately severe variants or a combination of a mild and a severe variant.12, 19 It has been hypothesized that the majority of the missing ABCA4 variants in individuals with STGD1 reside in intronic regions of the gene, and indeed, over the last few years, several groups have demonstrated the existence of such deep-intronic variants.4, 17, 20, 21, 22, 23 In 2013, Braun and colleagues22 described two variants in intron 30 (c.4539+2001G>A and c.4539+2028C>T, hereafter denoted M1 and M2, respectively) that supposedly could affect ABCA4 pre-mRNA splicing, but without providing experimental evidence. M2 thus far was identified in 13 case subjects.4, 17, 22, 23 M1 has been found in 31 case subjects and interestingly was particularly frequent in the Dutch and Belgian populations.4, 20, 21, 22, 23

Currently, several clinical trials for STGD1 are being conducted, employing different therapeutic strategies: (1) gene replacement therapy by delivering the complete ABCA4 cDNA (∼6.8 kb) via a lentiviral vector (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT01367444 and NCT01736592); (2) subretinal transplantation of human embryonic stem cell-derived retinal pigmented epithelial cells (hESC-RPE) (NCT02445612 and NCT02941991); and (3) administration of C20-D3-retinylacetate (NCT02402660). Each of these approaches have their limitations, and so far, no efficacy data have been reported from these clinical trials. An elegant alternative approach for some allelic subtypes of STGD1 would involve the modulation of ABCA4 pre-mRNA splicing by using antisense oligonucleotides (AONs). AONs are small molecules, complementary to their pre-mRNA target, that are able to interfere with splicing by either including or skipping (pseudo)exons.24 AONs have already been tested in vitro and in vivo to redirect aberrant splicing caused by a recurrent deep-intronic variant in CEP290 that leads to Leber congenital amaurosis (LCA [MIM: 611755]),25, 26, 27, 28 one of the most severe subtypes of retinal disease. In addition, AON-based splice correction has been demonstrated in cell lines from individuals carrying deep-intronic variants in USH2A (MIM: 608400)29 and OPA1 (MIM: 605290).30

In this study, we employed induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) technology to identify the splicing defect caused by the two neighboring ABCA4 variants (M1 and M2) in intron 30 and describe that the inclusion of the identified pseudoexon (PE) can be mitigated by administration of AONs to photoreceptor precursor cells derived from individuals with STGD1.

Material and Methods

Study Design

The objectives of this work are to: (1) detect the splice defect(s) caused by two neighboring variants in ABCA4 using photoreceptor precursor cells (PPCs) derived from affected individuals and (2) design and assess a splice modulation-based therapy to correct this splice defect using AONs. Skin biopsies were obtained of a healthy individual, and two affected individuals (P1 and P2) each carrying one of the deep-intronic mutations in a heterozygous manner. Fibroblast cells were grown, reprogrammed into iPSCs, and subsequently differentiated to PPCs. RNA analysis by RT-PCR was performed to reveal the insertion of a PE into the ABCA4 mRNA transcript. Four AONs and a sense oligonucleotide (SON) were designed to block exonic splicing enhancers (ESEs). Upon AON delivery, RNA analysis by RT-PCR was performed to assess the efficacy of the splicing redirection for each AON comparing non-treated and AON-treated samples. Two different concentrations of AONs were delivered to the cells. All experiments were performed simultaneously and under the same conditions for all cell lines. RNA analysis was performed in triplicate.

Subjects

Skin biopsies were collected from one Dutch control individual, a Dutch individual with STGD1 (P1) carrying the ABCA4 variants c.4539+2001G>A (p.?) (M1) and c.4892T>C (p.Leu1631Pro) (M3),21 and a person with STGD1 from the USA (P2) carrying a complex allele containing c.302+68C>T (p.?) and c.4539+2028C>T (p.?) (M2) and the deletion c.6148−698_6670delinsTGTGCACCTCCCTAG (p.?) (M4) on the other allele.23 Our research was conducted according to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. The procedures for obtaining human skin biopsies to establish primary fibroblasts cell lines were approved by the local Ethical Committee. Written informed consent was gathered from all participating individuals.

Reprogramming of Fibroblast Cells to Generate iPSCs

The culturing of fibroblast cells from the skin biopsies and their reprogramming into induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) were previously described.31 In essence, four lentiviral vectors containing the pluripotency genes OCT3/4, NANOG, KLF4, and c-MYC were employed for the transduction of fibroblasts.32

iPSC Differentiation into Photoreceptor Precursor Cells (PPCs)

After reaching confluence, iPSC clumps were digested with Accutase (cat. no. A6964, Sigma-Aldrich) and plated in a 12-well plate to form a monolayer. Upon reaching confluence, Essential-Flex E8 medium was changed into CI medium,33 consisting of DMEM/F12, supplemented with non-essential amino acids (NEAA, cat. no. M7145, Sigma Aldrich), B27 supplements (cat. no. 12587010, Thermo Fisher Scientific), N2 supplements (cat. no. 17502048, Thermo Fisher Scientific), 100 ng/μL insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1, cat. no. I3769, Sigma Aldrich), 10 ng/μL recombinant fibroblast growth factor basic (bFGF cat. no. F0291, Sigma Aldrich), 10 μg/μL Heparin (cat. no. H3149-10KU Sigma-Aldrich), and 200 μg/mL human recombinant COCO (cat. no. 3047-CC, R&D Systems). The medium was changed every day for 1 month, after which the cells were collected and characterized.

RNA Isolation and cDNA Synthesis

All RNA isolations were performed with the NucleoSpin RNA Clean-up Kit (cat. no. 740955-50, Macherey-Nagel) according to manufacturer’s protocol. RNA was quantified by nanodrop. One microgram of total RNA was used for all cDNA synthesis reactions. For quantitative PCR analysis (qPCR) and for semiquantitative RT-PCR analysis, cDNA was synthesized by the SuperScript VILO Master Mix (cat. no. 11755050, Thermo Fisher Scientific), following manufacturer’s instructions.

iPSC and PPC Characterization

q-PCR was performed to assess the pluripotency markers (in iPSCs) and differentiation markers (in PPCs) as described elsewhere.31 All primers used for the q-PCR analysis are listed in Table S1.

ABCA4 Transcript Analysis

After 30 days of differentiation, PPCs derived from normal individuals and from persons with STGD1 were harvested. Reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) analysis was performed using primers located in exon 2 (forward) and exon 5 (reverse); exon 30 (forward) and exon 31 (reverse); exon 33 (forward) and exon 35 (reverse); or exon 44 (forward) together with exon 46 (reverse) and exon 49 (reverse) of ABCA4. Actin (ACTB) primers were used as a control. Primer sequences are listed in Table S1. All cDNA reactions were diluted to 20 ng/μL by adding 30 μL of distilled water. For RT-PCR analysis, 80 ng of cDNA was used for all the ABCA4 reactions and 40 ng for the ACTB analysis. All reaction mixtures (25 μL) contained 10 μM of each primer pair, Taq DNA Polymerase 1 U/μL (cat. no. 11647679001, Roche), 10× PCR buffer with MgCl2, supplemented with 1 mM MgCl2, 2 μM dNTPs, and 80 or 40 ng cDNA. PCR conditions for ABCA4 fragments from exon 30 to 31 were as follows: 94°C for 2 min, 35 cycles of 30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 58°C and 90 s at 72°C, followed by a final step of 2 min at 72°C. For ABCA4 exon 44 to 46 or 49, as well as ACTB amplification, PCR was performed in the same conditions except for an elongation time of 30 s. 25 μL of the ABCA4 PCR product (exons 30 to 31), 15 μL of all the other ABCA4 products, and 10 μL of the actin amplicon were resolved on a 2% (w/v) agarose gel. The resulting bands were excised and purified with the NucleoSpin Gel & PCR cleanup kit (cat. no. 740609.250, Macherey-Nagel) according to manufacturer’s protocol. Purified PCR products were analyzed via Sanger sequencing, in a 3100 or 3730 DNA Analyzer (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Antisense Oligonucleotide (AON) Design

The sequence of the PE plus 50 base pairs flanking both sides were analyzed as described previously.34, 35 Briefly, the overall RNA structure of the region of interest was analyzed with the Mfold software, in order to identify partially open and closed regions. Splice enhancer motifs were determined using ESE finder 3.0. Special attention was paid to SC35 regions, as it has been demonstrated that there is a positive correlation between the presence of such motifs and the efficacy of AONs.34 Overall, this analysis led to the design of four AONs, two that overlap with the highest scoring SC35 motif (AON2 and AON3), one near the 5′ end of the PE (AON4), and one that overlaps with the c.4539+2001G>A mutation (AON1). The final AON sequences were also evaluated for the free energy of the molecule alone, the possibility to form dimers, and their interaction with the region of interest. For this, the RNA secondary structure tool of RNAstructure web server for RNA Secondary Structure Prediction was used. We ensured that all AONs had a free energy value above −4 on their own, above −14 as a dimer, and between 21 and 28 for the AON-region binding. This was calculated by using the estimated energy of the region of interest minus the energy of the AON bound to the region. All AON sequences had a length of 19 nucleotides with a Tm above 46°C and a GC content between 40% and 65%. The exact sequences and their properties are listed in Table 1. AONs were chemically modified by adding a phosphorothioate backbone and a 2-O-methyl sugar modification 2OMe/PS to each nucleotide and were purchased from Eurogentec (Liège, Belgium). AONs were dissolved in PBS (autoclaved twice) to a final concentration of 100 μM. A SON was ordered with the same chemistry to be used as a negative control.

Table 1.

Antisense Oligonucleotide (AON) Characteristics

| Name | Sequence 5′ -> 3′ | Length (bp) | % GC | Tm (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AON1 | ACAGGAGUCCUCAGCAUUG | 19 | 53 | 51.1 |

| AON2 | UUUUGUCCAGGGACCAAGG | 19 | 53 | 51.1 |

| AON3 | CUGUUACAUUUUGUCCAGG | 19 | 42 | 46.8 |

| AON4 | GGGGCACAGAGGACUGAGA | 19 | 63 | 55.4 |

| SON | CAAUGCUGAGGACUCCUGU | 19 | 53 | 51.1 |

AON Treatment

Following differentiation, PPCs were treated with AONs (0.5 and 1 μM) by mixing the naked AONs directly with the culturing medium. After 24 hr, cycloheximide (CHX, cat. no. C4859, Sigma Aldrich) was added at a final concentration of 0.1 mg/mL and cells were incubated for another 24 hr. 48 hr after AON delivery, cells were harvested and rinsed in PBS, and RNA was isolated. cDNA synthesis was performed using 1 μg of RNA, as described above. RT-PCR analysis was performed as described in the “ABCA4 transcript analysis” section. The ratio between correctly and aberrantly spliced variants was assessed by using Fiji software.36 For the analysis of the nucleotide traces, we used ContigExpress software.

Statistical Analysis

All results are represented as mean ± SD. Comparisons were performed using a two-tailed Mann-Whitney test. Statistically significant results were indicated with an asterisk (∗) when p < 0.05.

Results

Deep-Intronic Variants c.4539+2001G>A and c.4539+2028C>T Result in Pseudoexon Insertion

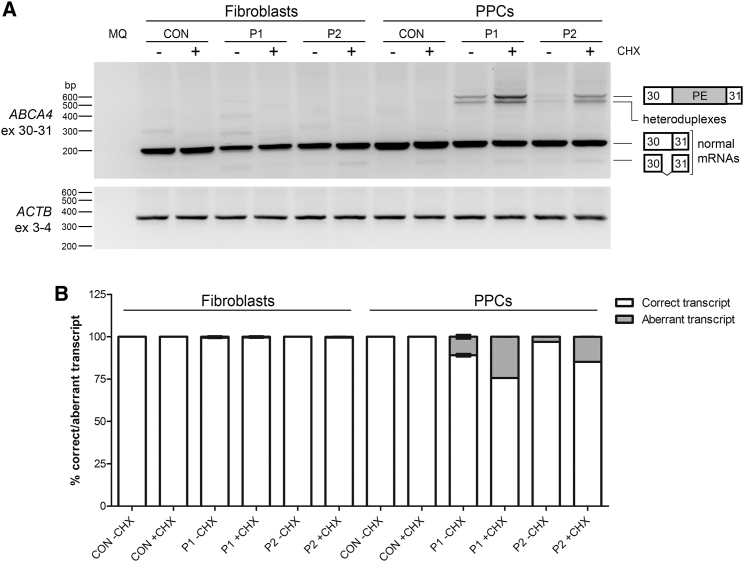

To determine whether variants c.4539+2001G>A (p.?) (M1) and c.4539+2028C>T (p.?) (M2) result in aberrant splicing of ABCA4 pre-mRNA, fibroblast cell lines were generated from two unrelated individuals with STGD1. Individual P1 was diagnosed with STGD1 and carried M1 and the missense variant M3, c.4892T>C (p.Leu1631Pro), in trans.14 Individual P2 was also diagnosed with STGD1 and carried M2 and a deep-intronic variant c.302+68C>T (p.?) in cis. In addition, P2 carried a genomic deletion, c.6148−698_6670delinsTGTGCACCTCCCTAG (p.?), denoted M4, which was present on the other allele.23 In addition, a fibroblast line from a healthy control was generated. All cells were cultured in the absence and presence of cycloheximide (CHX), a compound used to suppress nonsense-mediated decay of RNA products carrying protein-truncating mutations. RT-PCR analysis with primers located in exons 30 and 31 revealed only one clear product, corresponding to the expected product encompassing exons 30 and 31 (Figure 1). No aberrantly spliced products were detected in the fibroblasts from the individuals with STGD1.

Figure 1.

Identification of the Splice Defect Caused by Variants M1 and M2

(A) Reverse transcription (RT)-PCR on mRNA extracted from control, P1 (carrying variants M1: c.4539+2001G>A and M3: c.4892T>C), and P2 (carrying variants M2: c.4539+2028C>T and M4: c.6148−698_6670delinsTGTGCACCTCCCTAG)-derived fibroblasts and photoreceptor precursor cells (PPCs) using primers in exons 30 and 31 of ABCA4. For both P1- and P2-derived PPCs, some aberrantly spliced bands were detected, especially after cycloheximide (CHX) treatment (+). Actin (ACTB) RT-PCR was used as a control. Heteroduplexes contain transcripts with the pseudoexon together with the correct spliced transcript (exons 30 and 31) and the truncated splice variant of exon 30 that lacks the 3′ 73 nt of exon 30 (r.4467_4539del [p.Cys1490Glufs∗12]).

(B) Semi-quantification of the ratio of correctly and aberrantly spliced ABCA4 transcript for each cell line with and without CHX.

Error bars indicate standard deviation.

Recent studies have shown that the retina has a complex splicing system, resulting in a tissue- or even cell type-specific recognition of splice sites and subsequent inclusion of (pseudo)exons.28, 37 To further investigate potentially retina-specific splicing defects caused by the two deep-intronic ABCA4 mutations, control and STGD1 fibroblasts were reprogrammed into induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) via lentiviral transduction of the Yamanaka factors.32 Quantitative PCR (q-PCR) (Figure S1A) validated the pluripotency of the iPSCs. Subsequently, these iPSCs were differentiated for 1 month into photoreceptor precursor cells (PPCs). We used the protocol described previously by Flamier and colleagues33 to obtain a mixed population of cone precursors and retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cells. Characterization of PPCs derived from a control and affected individuals P1 and P2 revealed a significantly increased expression of ABCA4, being ∼35 times higher in the control PPCs than control iPSCs and ∼10 and 8 times higher in P1 and P2 PPCs, respectively, compared with P1 and P2 iPSCs. High expression of neural retinal precursor markers PAX6, OTX2, and CRX (the latter one only in control and P1) indicated the still immature stage of PPCs, while the enrichment of RPE65 mRNA and increase of VMD2 mRNA confirmed the presence of some RPE cells. Increased expression of OPN1SW, PDE6H, and NRL in all cell lines also indicated the presence of more mature cone and rod cells. PDE6C and RHO were only slightly enriched in P1 and P2, while RCV1 (photoreceptor marker), NR2E3 (precursor of rod cells), and OPN1MLW (green and red cone marker) were increased only in P2 (Figure S1B).

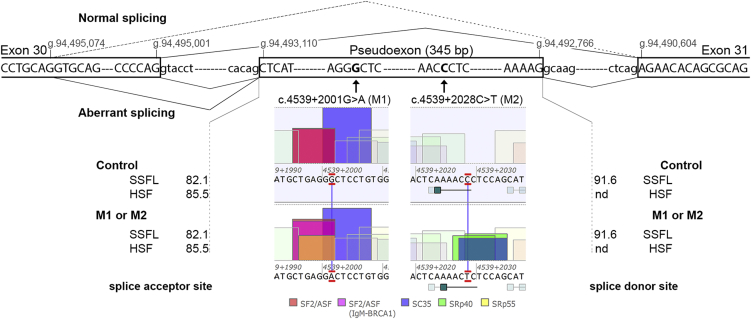

As ABCA4 was robustly expressed in all three differentiated cultures, we performed RT-PCR analysis from exon 30 to exon 31, which showed aberrant transcripts in both P1- and P2-derived PPCs upon CHX treatment, but not in control PPCs (Figure 1A). Semi-quantification of the ratio between correctly and aberrantly spliced variants in the CHX-treated samples revealed that ∼25% of ABCA4 transcripts in P1 carrying M1 and ∼15% of ABCA4 transcripts in P2 carrying M2 were aberrant (Figure 1B). A more detailed analysis of all bands by Sanger sequencing revealed a PE of 345 nt containing a premature stop codon (Figure 2), which is predicted to result in the truncated protein product p.Arg1514Leufs∗36. Interestingly, both variants included the same PE in the mRNA transcript upon CHX treatment. Once the sequence was identified, we studied the effect of both variants on splicing. According to all prediction softwares, neither M1 nor M2 changed the strength of the splice acceptor and donor site (see Figure 2). The splice donor site of the 345-nt PE contains “GC” as canonical splice site sequence, which is recognized only by the SpliceSiteFinder-Like (SSFL) software. Further in silico predictions showed that M1 enhances an exonic splicing enhancer SF2 site and creates a new SRp55 motif, whereas M2 creates one SC35 and two SRp40 motifs (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

In Silico Characterization of the Effect Caused by Two Deep-Intronic Variants

Schematic representation of the boundaries of the 345-bp pseudoexon, with the location of the variants M1 (c.4539+2001G>A) and M2 (c.4539+2028C>T), the genomic positions of the splice sites, the splicing events detected, and the splice site predictions for both acceptor and donor sites. The dashed line represents the splicing from a cryptic splice donor site in exon 30 at position g.94,495,074 (GRCh37/hg19) to the normal splice acceptor site of exon 31 (r.4467_4539del [p.Cys1490Glufs∗12]). The predicted values of the splice acceptor and donor sites in the control and mutant situations did not show any difference. In the middle panels, the effects of the variants enhancing or creating new ESE motifs are depicted. Abbreviations: SSFL, SpliceSiteFinder-like; HSF, Human Splicing Finder; nd, not detected.

Subsequent in-depth analysis of all the bands observed by RT-PCR revealed one band that contained heteroduplexes of the correctly spliced transcript together with the one containing the PE (Figure 1). Moreover, an extra faint band lacking the last 73 bp of exon 30 was found in all samples treated with CHX, including the control. A relatively weak splice donor site (Human Splicing Finder [HSF] score: 75.9) explains this alternative transcript that was also detected in the heteroduplex band (Figure 1). This splice product (r.4467_4539del [p.Cys1490Glufs∗12]) was also identified as a result of non-canonical splice site variants at the “natural” splice donor site of exon 30. Interestingly, this new donor site was previously reported as a splice acceptor site (HSF score: 89.6) creating an isoform lacking the first 114 bp of exon 30.38

The c.302+68C>T Variant Does Not Result in Qualitative Differences of the mRNA

In seven STGD1-affected case subjects with M2 in whom this was investigated, c.302+68C>T (p.?) was found in cis.4, 22, 23 To study the contribution of this variant to STGD1 pathology, we performed RT-PCR of mRNA from control PPCs and P1 and P2 PPCs, treated and untreated with CHX, as well as from adult retina mRNA. As shown in Figure S2, PCR primers located in exons 2 and 5 generated a canonical splice product of 459 nt, as well as a smaller fragment of 317 nt, in all PPCs and in human retina. Validation of the bands by Sanger sequencing revealed that the 317-nt fragment was lacking exon 3 (size: 142 bp). No other splice products were observed, indicating that the c.302+68C>T variant does not result in the activation of cryptic splice sites and/or exonic splice enhancers.

Antisense Oligonucleotides Block M1- and M2-Associated Pseudoexon Insertion

Once the molecular mechanism associated with M1 and M2 variants was elucidated, we aimed to design a therapeutic approach, based on splicing modulation, to skip the PE. An attractive and efficient method is the use of AONs, small RNA molecules that are able to enter the cell, bind to the pre-mRNA, and modify the splicing pattern. In order to increase their binding affinity and avoid RNaseH activation (and therefore transcript degradation), we used 2-O-methyl-modified RNA AONs with phosphorothioate (2OMe/PS) backbones, as previously reported.25, 26, 27, 29 In total we designed four AONs to block several SC35 motifs or the newly created SRp55 motif due to M1 (AON1; Figure 3A). In addition, a sense oligonucleotide (SON), complementary to AON1 and containing the same chemical modifications as the other AONs but not able to bind to the pre-mRNA, was designed in the same region. AONs and SON were delivered to ∼1 month differentiated PPCs and after 48 hr, the RNA was analyzed. As expected, CHX treatment increased the presence of aberrantly spliced transcript in the non-treated cells (Figures 3B and 3C). In addition, there were no differences between the non-treated and the SON-treated cells. We found that AON4 was efficiently able to produce up to ∼75% PE skipping in both cell lines at two different concentrations (Figure 3D), while AON1 was very efficient only in the M1 cell line. AON2 showed variable efficacy and was less effective at a higher concentration, while AON3 was poorly able to redirect splicing both at 0.5 μM and 1 μM (Figures 3B–3D). One explanation for AON2 and AON3 showing such different behavior despite targeting the same region could be the AON properties (Table 1). AON3 compared with AON2 has a low GC content and Tm, which might affect the stability and binding capacity, therefore explaining its low efficiency.

Figure 3.

Effect of Antisense Oligonucleotide Delivery at mRNA in Photoreceptor Precursor Cells

(A) Schematic representation of the pseudoexon, indicating the location of the variants, the SC35 motifs with the highest scores, and the positions of the antisense oligonucleotides (AONs).

(B) RNA analysis on AON-treated cells. RT-PCR from exon 30 to exon 31 of ABCA4 mRNA in control, P1 (M1: c.4539+2001G>A and M3: c.4892T>C), and P2 (M2: c.4539+2028C>T and M4: c.6148−698_6670delinsTGTGCACCTCCCTAG)-derived photoreceptor precursor cells (PPCs) upon AON delivery. Actin (ACTB) mRNA amplification was used to normalize samples. Abbreviations: NT-, non-treated and in the absence of cycloheximide (CHX); NT+, non-treated in the presence of CHX; A1, AON1; A2, AON2; A3, AON3; A4, AON4; S, SON; and MQ, PCR negative control. Heteroduplexes contain transcripts with the pseudoexon together with the correct spliced transcript (exons 30 and 31) and the truncated splice variant of exon 30 that lacks the 3′ 73 nt of exon 30 (r.4467_4539del [p.Cys1490Glufs∗12]).

(C) Semi-quantification of the ratio of correctly versus aberrantly spliced transcripts in all P1 and P2 samples.

(D) Percentage of correction of each AON compared to the NT+ based on the ratio observed in (C). Statistical differences in the efficacy of the AONs for M1 and M2 are indicated with an asterisk (∗p < 0.05 using Mann-Whitney test).

All histograms illustrate the average ± standard deviation.

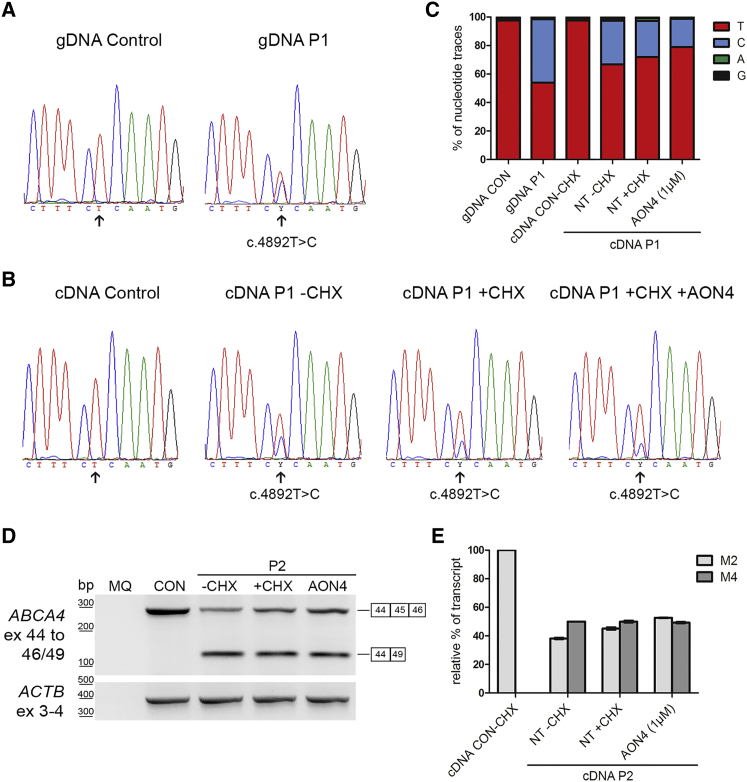

Assessment of the AON Efficacy

P1-derived PPCs carried M1 and M3 in trans; P2-derived PPCs carried M2 and M4 in trans. In order to determine whether the observed decrease in PE-containing transcripts resulted in an increase of wild-type ABCA4 transcripts, we analyzed the ABCA4 mRNA levels of all alleles (Figure 4). We sequenced the region encompassing M3 (c.4892T>C [p.Leu1631Pro]) from genomic DNA of a control person and P1 (Figure 4A) and we sequenced the cDNA of control person-derived PPCs and P1-derived PPCs without and with CHX treatment, as well as the sample treated with 1 μM of AON4 (Figure 4B). By assessing the nucleotide traces in each peak using ContigExpress software, it was observed that the ratio between both alleles in genomic DNA of P1 was ∼1:1 (Figure 4C). In contrast, the cDNA sequences showed that the ratio of c.4892T (M1 allele) and c.4892C (M3 allele) was ∼2:1 in the absence of CHX. The fact that the M3 allele is not predicted to undergo NMD and that it is lower expressed compared to M1 suggests an allelic imbalance between the M1 and M3 alleles. When treating the cells with CHX, the levels of the M1 allele increased to a ratio of ∼3:1, indicating that the M1 allele with the 345-nt insertion is subjected to NMD. Finally, the amount of M1 allele-derived mRNA after AON treatment increased to a ratio ∼4:1, suggesting that the AON was able to really convert aberrantly spliced transcripts into correctly spliced transcripts, thereby increasing the wild-type mRNA levels of this allele.

Figure 4.

AON Rescue in Photoreceptor Precursor Cells Based on the Analysis of the mRNA Alleles Associated with Variants M1/M3 and M2/M4

(A–C) Assessment of the mRNA product carrying variant M3, c.4892T>C (p.Leu1631Pro) which is in trans with M1. Chromatograms (A) of the reverse sequence of genomic DNA (gDNA) in a control and individual P1 carrying M1 and M3. Chromatograms (B) of the sequence of the cDNA of the photoreceptor precursor cells (PPC) from the control cell line and from P1 PPCs in the absence (−) or presence (+) of cycloheximide (CHX) and 1 μM of AON4 (+AON4). The arrow indicates the position of the double peak where the M3 variant is located.

(C) Graphical representation of the traces of each nucleotide in the sequence using ContigExpress software.

(D and E) Semi-quantification of mRNA products associated with variants M2 and M4 in P2.

(D) P2 PPCs carry M2 and c.6148–698_6670delinsTGTGCACCTCCCTAG (p.Val2050_Gln2243del) in trans. RT-PCR of the control (CON) and P2 PPCs without (−) or with (+) CHX and AON4 at 1 μM using the same forward primer in exon 44 and a reverse primer in exon 46 (that is not present in M4 genomic DNA nor in the mRNA product) and a reverse primer in exon 49. The upper band represents the correct spliced transcript from exon 44 to 46 corresponding to the M2 allele, while the lower band is the resulting transcript caused by the multi-exon deletion. An RT-PCR product of ACTB was used as loading control.

(E) Graphical representation of the semi-quantification of the bands observed in (D). The mRNA product observed in the control (exons 44 to 46) was set at 100%, while the mRNA product from the M4 allele (exons 44 to 49) was set at 50% in the P2-PPCs –CHX condition. The mRNA product from allele M4 is not sensitive to NMD suppression. The correctly spliced transcripts from allele M2 increase upon NMD suppression (+CHX versus −CHX) of cultured PPCs and increase even more upon AON4 treatment.

Error bars represent standard deviation for each condition.

To analyze the mRNA products of alleles M2 and M4 in P2-derived PPCs, we amplified them separately to identify the mRNA defect due to variant M4 (c.6148−698_6670delinsTGTGCACCTCCCTAG [p.?]). By conducting a PCR from exon 44 to exon 49, we could determine that M4 results in an in-frame mRNA deletion of exons 45 to 48, resulting in a predicted shorter protein p.Val2050_Gln2243del (Figure 4D). Given the fact that this deletion does not alter the reading frame, the M4 allele is not predicted to undergo NMD. In order to detect and compare the effect of NMD and AON-rescue in both alleles, we performed a PCR using two reverse primers and cDNA of P2-derived PPCs (Figure 4D). Our results showed that the allele carrying the M4-associated mRNA deletion was expressed at similar levels in P2 PPCs with and without CHX, suggesting that the mRNA from allele M4 was not degraded by NMD (Figure 4E). Also, in the presence of AON4, no changes were observed. When we specifically amplified the M2-mRNA allele, we did identify an increase after CHX treatment. This indicates that the M2-associated mRNA carrying the 345-nt insertion undergoes NMD as was previously shown. The fact that upon AON treatment, the level of the M2-associated mRNA allele increased clearly indicates that more wild-type transcript without the 345-nt insertion was produced. The M2-associated mRNA level increased up to ∼50% when compared to the control mRNA level (Figure 4E).

Discussion

In this study we showed that two neighboring deep-intronic variants in ABCA4, c.4539+2001G>A and c.4539+2028C>T, result in a retina-specific inclusion of a 345-nt PE in a proportion of ABCA4 transcripts. This PE, which is predicted to lead to protein truncation (p.Arg1514Leufs∗36), was found as a low-abundance alternative splice form of ABCA4 when performing deep RNA sequencing of human macula RNA.22 RT-PCR product quantification revealed more PE insertion due to M1 than to M2. We listed the 12 published individuals with STGD1 carrying bi-allelic ABCA4 variants among which was M1 (n = 12) in Table S2.20, 21 Considering the assessment of the severity of the variants present in trans, there is little doubt that M1 acts as a severe variant. Based on the clinical and genetic data available for four persons with STGD1 carrying M2 (Table S2),23 it could also act as a severe variant, but the dataset is too small to draw a definite conclusion. We thus would expect that the amount of mutant mRNA in P1 carrying M1, who carries a missense variant in trans, should be equal to the amount of correct product. This is not the case, yet this comparison is difficult, as smaller products amplify more effectively and NMD suppression may be incomplete. Nevertheless, by Sanger sequencing validation of the second allele, we observed that in PPCs, the M1 mRNA allele is higher expressed and subjected to NMD, since it is increased upon CHX treatment. Intriguingly, we also noticed an allelic imbalance between the M1 and M3 alleles in the cells of P1. As M3 is a missense change that is not predicted to undergo NMD, the fact that it appears to be lower expressed compared to M1 suggests that there may be a difference in the transcriptional regulation between the two ABCA4 alleles. Alternatively, the mRNA stability of the M3 allele may be reduced. Thus the pathogenicity of the M3 allele may not only be due to the amino acid substitution, but rather to other, yet unknown, factors.

The PE insertion due to M2 is less prominent than that of M1, which may suggest that it has a less severe character. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that other cis-acting variants missed during locus sequencing4 act in concert with these intron 30 variants. In addition, other as yet unknown cell type-specific mechanisms may play a role. One likely explanation is that the PPCs that were generated may not yet fully reflect the in vivo situation of the retina, as these were cultured for only 30 days. Given that some protocols in which cells have been differentiated for a longer time resulted in a more mature type of photoreceptor cells,28, 39, 40, 41 a longer differentiation of cells derived from P2 (and perhaps also P1) would likely show an increase of PE-containing ABCA4 transcripts. The importance of retinal differentiation for PE recognition was also clearly illustrated for the deep-intronic c.2991+1655A>G variant in CEP290. Whereas in lymphoblastoid and fibroblast cells of individuals harboring this mutation homozygously the ratio between correctly and aberrantly spliced CEP290 is ∼1:1,25, 26, 42 in iPSC-derived photoreceptor cells, the amount of aberrantly spliced CEP290 was found to be drastically increased (∼1:4 ratio).28 This study not only revealed insights into why this mutation, despite a ubiquitous expression of CEP290, resulted in a non-syndromic retinal phenotype, but also demonstrated the enormous power of using iPSC-derived retinal cells from affected individuals to study splice defects in a relevant cellular system.

Previous IRD-associated intronic variants have created new splice acceptor or donor sites that allowed the insertion of a PE.22, 30, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50 To our knowledge we are the first to report on the insertion of a PE that is not due to this mechanism but possibly because of the creation of new ESE motifs in IRDs. Previously, the loss of an ESE and the creation of a splicing suppressor has been reported in the OPN1LW/OPN1MW gene array due to the coding variant c.532A>G (p.Ile178Val), which is associated with exon 3 exclusion and a congenital color vision defect (MIM: 303800 and 303900).51, 52, 53 Intronic regions are riddled with pairs of predicted splice acceptor and donor sites that theoretically could flank a PE. Upon the identification of additional PEs that are not activated through the creation of splice sites, it will be possible to determine the sequence motifs that render cryptic PEs into real PEs.

The M1- and M2-associated PE insertions were successfully blocked by AONs. Previously, we estimated that mild alleles have a residual ABCA4 activity of between 50% and 80%.54 Assuming that the second allele is severe, this means that at the cellular level, ∼40% of wild-type ABCA4 protein should be sufficient for normal function. Our AON approach was able to rescue 80% of the observed splice defect and thus suggests that therapeutic levels can be reached. Intriguingly, a M1-specific AON was effective only in the P1 cell line. Even with a doubled AON concentration, AON1 was still unable to correct the splice defect in the P2 cell line. These results highlight the specificity of the sequence and the fact that a single nucleotide mismatch is enough to change the efficacy of an AON. The newly created SRp55 motif may play a crucial role in the detection of the PE. Given the fact that both variants activate the same PE and AON4 is able to skip the PE in both cases, this remains to be further elucidated. One of the limitations of AONs is that they bind to specific sequences and therefore it is not possible to test the same AON in animal models if there is no conserved DNA/RNA region, unless a model is created in which part of the human sequence is inserted at the orthologous position in the animal genome. However, it is already known that the 2OMe/PS chemistry and 2MOE (2-O-Methoxyethyl)/PS are not toxic for the eye as shown in several animal models.26, 55, 56 Furthermore, the first AON commercialized was used to treat the eye condition CMV-retinitis.57 Thus, AON technology seems to be a safe and promising approach to treat eye disorders. Owing to the lack of animal models, the use of iPSC-derived photoreceptors appears to be a suitable alternative, although it still needs to be elucidated whether the function of ABCA4 can be restored following treatment of these cells.

In conclusion, by using early cones and RPE cells derived from individuals with STGD1, we were able to identify the molecular defect due to two recurrent deep-intronic neighboring variants underlying STGD1. The splice defect consisted of the insertion of a 345-nt PE which appears to be retina- specific and is most likely caused by the presence of newly generated exonic splicing enhancers, instead of by the creation of novel splice sites. Moreover, an AON-based therapeutic approach was designed and tested, showing that one AON was able to redirect the splice defect in both mutated cell lines. Furthermore, a variant-specific AON was very effective against M1 but not M2, indicating that one single nucleotide mismatch can change the AON efficiency drastically. Overall, these results highlight the potential of AONs as a therapeutic tool for Stargardt disease.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Saskia van der Velde-Visser, Marlie Jacobs-Camps, Anke van Dijk, Angelique Goercharn-Ramlal, Tessa van der Heijden, Hind Almushattat, Simon van Reijmersdal, and Lonneke Duijkers for technical assistance. This work was supported by the FP7-PEOPLE-2012-ITN programme EyeTN, agreement 317472 (to F.P.M.C.), the Macula Vision Research Foundation (to F.P.M.C.), the Rotterdamse Stichting Blindenbelangen, the Stichting Blindenhulp, and the Stichting tot Verbetering van het Lot der Blinden (to F.P.M.C. and S.A.), and by the Landelijke Stichting voor Blinden en Slechtzienden, Macula Degeneratie fonds, and the Stichting Blinden-Penning that contributed through Uitzicht 2016-12 (to F.P.M.C. and S.A.). This work was also supported by the Algemene Nederlandse Vereniging ter Voorkoming van Blindheid, Stichting Blinden-Penning, Landelijke Stichting voor Blinden en Slechtzienden, Stichting Oogfonds Nederland, Stichting Macula Degeneratie Fonds, and Stichting Retina Nederland Fonds that contributed through UitZicht 2015-31, together with the Rotterdamse Stichting Blindenbelangen, Stichting Blindenhulp, Stichting tot Verbetering van het Lot der Blinden, Stichting voor Ooglijders, and Stichting Dowilvo (to A.G. and R.W.J.C.), and the Stichting Macula Degeneratie Fonds and the Stichting A.F. Deutman Researchfonds Oogheelkunde (to C.B.H.). This work was also supported by the Foundation Fighting Blindness USA, grant no. PPA-0517-0717-RAD (to A.G., C.B.H., F.P.M.C., R.W.J.C., and S.A.). R.A. was supported, in part, by grants from the National Eye Institute/NIH EY019861 and EY019007 (Core Support for Vision Research) and unrestricted funds from Research to Prevent Blindness (New York, NY) to the Department of Ophthalmology, Columbia University. The funding organizations had no role in the design or conduct of this research. They provided unrestricted grants. R.W.J.C., A.G., F.P.M.C., and S.A. are inventors on a filed patent (No. 16203864.0) that is related to the contents of this manuscript.

Published: March 8, 2018

Footnotes

Supplemental Data include two figures and two tables and can be found with this article online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2018.02.008.

Web Resources

ClinicalTrials.gov, https://clinicaltrials.gov

ESE finder 3.0, http://krainer01.cshl.edu/cgi-bin/tools/ESE3/esefinder.cgi?process=home

OMIM, http://www.omim.org/

RNAstructure, https://rna.urmc.rochester.edu/RNAstructureWeb/index.html

Supplemental Data

References

- 1.Fishman G.A., Stone E.M., Grover S., Derlacki D.J., Haines H.L., Hockey R.R. Variation of clinical expression in patients with Stargardt dystrophy and sequence variations in the ABCR gene. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1999;117:504–510. doi: 10.1001/archopht.117.4.504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stargardt K. Über familiäre, progressive Degeneration in der Maculagegend des Auges. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 1909;71:534–550. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allikmets R., Singh N., Sun H., Shroyer N.F., Hutchinson A., Chidambaram A., Gerrard B., Baird L., Stauffer D., Peiffer A. A photoreceptor cell-specific ATP-binding transporter gene (ABCR) is mutated in recessive Stargardt macular dystrophy. Nat. Genet. 1997;15:236–246. doi: 10.1038/ng0397-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zernant J., Xie Y.A., Ayuso C., Riveiro-Alvarez R., Lopez-Martinez M.A., Simonelli F., Testa F., Gorin M.B., Strom S.P., Bertelsen M. Analysis of the ABCA4 genomic locus in Stargardt disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2014;23:6797–6806. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Molday R.S., Beharry S., Ahn J., Zhong M. Binding of N-retinylidene-PE to ABCA4 and a model for its transport across membranes. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2006;572:465–470. doi: 10.1007/0-387-32442-9_64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cremers F.P.M., van de Pol D.J., van Driel M., den Hollander A.I., van Haren F.J., Knoers N.V., Tijmes N., Bergen A.A., Rohrschneider K., Blankenagel A. Autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa and cone-rod dystrophy caused by splice site mutations in the Stargardt’s disease gene ABCR. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1998;7:355–362. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.3.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maugeri A., Klevering B.J., Rohrschneider K., Blankenagel A., Brunner H.G., Deutman A.F., Hoyng C.B., Cremers F.P.M. Mutations in the ABCA4 (ABCR) gene are the major cause of autosomal recessive cone-rod dystrophy. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2000;67:960–966. doi: 10.1086/303079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martínez-Mir A., Paloma E., Allikmets R., Ayuso C., del Rio T., Dean M., Vilageliu L., Gonzàlez-Duarte R., Balcells S. Retinitis pigmentosa caused by a homozygous mutation in the Stargardt disease gene ABCR. Nat. Genet. 1998;18:11–12. doi: 10.1038/ng0198-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shroyer N.F., Lewis R.A., Lupski J.R. Analysis of the ABCR (ABCA4) gene in 4-aminoquinoline retinopathy: is retinal toxicity by chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine related to Stargardt disease? Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2001;131:761–766. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(01)00838-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duncker T., Tsang S.H., Lee W., Zernant J., Allikmets R., Delori F.C., Sparrow J.R. Quantitative fundus autofluorescence distinguishes ABCA4-associated and non-ABCA4-associated bull’s-eye maculopathy. Ophthalmology. 2015;122:345–355. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lewis R.A., Shroyer N.F., Singh N., Allikmets R., Hutchinson A., Li Y., Lupski J.R., Leppert M., Dean M. Genotype/phenotype analysis of a photoreceptor-specific ATP-binding cassette transporter gene, ABCR, in Stargardt disease. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1999;64:422–434. doi: 10.1086/302251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maugeri A., van Driel M.A., van de Pol D.J., Klevering B.J., van Haren F.J., Tijmes N., Bergen A.A., Rohrschneider K., Blankenagel A., Pinckers A.J. The 2588G-->C mutation in the ABCR gene is a mild frequent founder mutation in the Western European population and allows the classification of ABCR mutations in patients with Stargardt disease. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1999;64:1024–1035. doi: 10.1086/302323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rivera A., White K., Stöhr H., Steiner K., Hemmrich N., Grimm T., Jurklies B., Lorenz B., Scholl H.P., Apfelstedt-Sylla E., Weber B.H. A comprehensive survey of sequence variation in the ABCA4 (ABCR) gene in Stargardt disease and age-related macular degeneration. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2000;67:800–813. doi: 10.1086/303090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Webster A.R., Héon E., Lotery A.J., Vandenburgh K., Casavant T.L., Oh K.T., Beck G., Fishman G.A., Lam B.L., Levin A. An analysis of allelic variation in the ABCA4 gene. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2001;42:1179–1189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zernant J., Schubert C., Im K.M., Burke T., Brown C.M., Fishman G.A., Tsang S.H., Gouras P., Dean M., Allikmets R. Analysis of the ABCA4 gene by next-generation sequencing. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2011;52:8479–8487. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-8182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fujinami K., Zernant J., Chana R.K., Wright G.A., Tsunoda K., Ozawa Y., Tsubota K., Webster A.R., Moore A.T., Allikmets R., Michaelides M. ABCA4 gene screening by next-generation sequencing in a British cohort. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2013;54:6662–6674. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-12570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schulz H.L., Grassmann F., Kellner U., Spital G., Rüther K., Jägle H., Hufendiek K., Rating P., Huchzermeyer C., Baier M.J. Mutation spectrum of the ABCA4 gene in 335 Stargardt disease patients from a multicenter German cohort-impact of selected deep intronic variants and common SNPs. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2017;58:394–403. doi: 10.1167/iovs.16-19936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zernant J., Lee W., Collison F.T., Fishman G.A., Sergeev Y.V., Schuerch K., Sparrow J.R., Tsang S.H., Allikmets R. Frequent hypomorphic alleles account for a significant fraction of ABCA4 disease and distinguish it from age-related macular degeneration. J. Med. Genet. 2017;54:404–412. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2017-104540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Driel M.A., Maugeri A., Klevering B.J., Hoyng C.B., Cremers F.P.M. ABCR unites what ophthalmologists divide(s) Ophthalmic Genet. 1998;19:117–122. doi: 10.1076/opge.19.3.117.2187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bauwens M., De Zaeytijd J., Weisschuh N., Kohl S., Meire F., Dahan K., Depasse F., De Jaegere S., De Ravel T., De Rademaeker M. An augmented ABCA4 screen targeting noncoding regions reveals a deep intronic founder variant in Belgian Stargardt patients. Hum. Mutat. 2015;36:39–42. doi: 10.1002/humu.22716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bax N.M., Sangermano R., Roosing S., Thiadens A.A., Hoefsloot L.H., van den Born L.I., Phan M., Klevering B.J., Westeneng-van Haaften C., Braun T.A. Heterozygous deep-intronic variants and deletions in ABCA4 in persons with retinal dystrophies and one exonic ABCA4 variant. Hum. Mutat. 2015;36:43–47. doi: 10.1002/humu.22717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Braun T.A., Mullins R.F., Wagner A.H., Andorf J.L., Johnston R.M., Bakall B.B., Deluca A.P., Fishman G.A., Lam B.L., Weleber R.G. Non-exomic and synonymous variants in ABCA4 are an important cause of Stargardt disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2013;22:5136–5145. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee W., Xie Y., Zernant J., Yuan B., Bearelly S., Tsang S.H., Lupski J.R., Allikmets R. Complex inheritance of ABCA4 disease: four mutations in a family with multiple macular phenotypes. Hum. Genet. 2016;135:9–19. doi: 10.1007/s00439-015-1605-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hammond S.M., Wood M.J. Genetic therapies for RNA mis-splicing diseases. Trends Genet. 2011;27:196–205. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Collin R.W.J., den Hollander A.I., van der Velde-Visser S.D., Bennicelli J., Bennett J., Cremers F.P.M. Antisense oligonucleotide (AON)-based therapy for Leber congenital amaurosis caused by a frequent mutation in CEP290. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids. 2012;1:e14. doi: 10.1038/mtna.2012.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garanto A., Chung D.C., Duijkers L., Corral-Serrano J.C., Messchaert M., Xiao R., Bennett J., Vandenberghe L.H., Collin R.W. In vitro and in vivo rescue of aberrant splicing in CEP290-associated LCA by antisense oligonucleotide delivery. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2016;25:2552–2563. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddw118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gerard X., Perrault I., Hanein S., Silva E., Bigot K., Defoort-Delhemmes S., Rio M., Munnich A., Scherman D., Kaplan J. AON-mediated exon skipping restores ciliation in fibroblasts harboring the common Leber congenital amaurosis CEP290 mutation. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids. 2012;1:e29. doi: 10.1038/mtna.2012.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parfitt D.A., Lane A., Ramsden C.M., Carr A.J., Munro P.M., Jovanovic K., Schwarz N., Kanuga N., Muthiah M.N., Hull S. Identification and correction of mechanisms underlying inherited blindness in human iPSC-derived optic cups. Cell Stem Cell. 2016;18:769–781. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Slijkerman R.W., Vaché C., Dona M., García-García G., Claustres M., Hetterschijt L., Peters T.A., Hartel B.P., Pennings R.J., Millan J.M. Antisense oligonucleotide-based splice correction for USH2A-associated retinal degeneration caused by a frequent deep-intronic mutation. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids. 2016;5:e381. doi: 10.1038/mtna.2016.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bonifert T., Gonzalez Menendez I., Battke F., Theurer Y., Synofzik M., Schöls L., Wissinger B. Antisense oligonucleotide mediated splice correction of a deep intronic mutation in OPA1. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids. 2016;5:e390. doi: 10.1038/mtna.2016.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sangermano R., Bax N.M., Bauwens M., van den Born L.I., De Baere E., Garanto A., Collin R.W.J., Goercharn-Ramlal A.S., den Engelsman-van Dijk A.H., Rohrschneider K. Photoreceptor progenitor mRNA analysis reveals exon skipping resulting from the ABCA4 c.5461-10T→C mutation in Stargardt disease. Ophthalmology. 2016;123:1375–1385. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.01.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takahashi K., Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Flamier A., Barabino A., Gilbert B. Differentiation of human embryonic stem cells into cone photoreceptors. Bio Protoc. 2016;6:e1870. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aartsma-Rus A. Overview on AON design. Methods Mol. Biol. 2012;867:117–129. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-767-5_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Garanto A., Collin R.W.J. Design and in vitro use of antisense oligonucleotides to correct pre-mRNA splicing defects in inherited retinal dystrophies. Methods Mol. Biol. 2018;1715:61–78. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-7522-8_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schindelin J., Arganda-Carreras I., Frise E., Kaynig V., Longair M., Pietzsch T., Preibisch S., Rueden C., Saalfeld S., Schmid B. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:676–682. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Murphy D., Cieply B., Carstens R., Ramamurthy V., Stoilov P. The Musashi 1 controls the splicing of photoreceptor-specific exons in the vertebrate retina. PLoS Genet. 2016;12:e1006256. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gerber S., Rozet J.M., van de Pol T.J., Hoyng C.B., Munnich A., Blankenagel A., Kaplan J., Cremers F.P.M. Complete exon-intron structure of the retina-specific ATP binding transporter gene (ABCR) allows the identification of novel mutations underlying Stargardt disease. Genomics. 1998;48:139–142. doi: 10.1006/geno.1997.5164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meyer J.S., Howden S.E., Wallace K.A., Verhoeven A.D., Wright L.S., Capowski E.E., Pinilla I., Martin J.M., Tian S., Stewart R. Optic vesicle-like structures derived from human pluripotent stem cells facilitate a customized approach to retinal disease treatment. Stem Cells. 2011;29:1206–1218. doi: 10.1002/stem.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tucker B.A., Mullins R.F., Streb L.M., Anfinson K., Eyestone M.E., Kaalberg E., Riker M.J., Drack A.V., Braun T.A., Stone E.M. Patient-specific iPSC-derived photoreceptor precursor cells as a means to investigate retinitis pigmentosa. eLife. 2013;2:e00824. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhong X., Gutierrez C., Xue T., Hampton C., Vergara M.N., Cao L.H., Peters A., Park T.S., Zambidis E.T., Meyer J.S. Generation of three-dimensional retinal tissue with functional photoreceptors from human iPSCs. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:4047. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.den Hollander A.I., Koenekoop R.K., Yzer S., Lopez I., Arends M.L., Voesenek K.E., Zonneveld M.N., Strom T.M., Meitinger T., Brunner H.G. Mutations in the CEP290 (NPHP6) gene are a frequent cause of Leber congenital amaurosis. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2006;79:556–561. doi: 10.1086/507318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Webb T.R., Parfitt D.A., Gardner J.C., Martinez A., Bevilacqua D., Davidson A.E., Zito I., Thiselton D.L., Ressa J.H., Apergi M. Deep intronic mutation in OFD1, identified by targeted genomic next-generation sequencing, causes a severe form of X-linked retinitis pigmentosa (RP23) Hum. Mol. Genet. 2012;21:3647–3654. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van den Hurk J.A., van de Pol D.J., Wissinger B., van Driel M.A., Hoefsloot L.H., de Wijs I.J., van den Born L.I., Heckenlively J.R., Brunner H.G., Zrenner E. Novel types of mutation in the choroideremia ( CHM) gene: a full-length L1 insertion and an intronic mutation activating a cryptic exon. Hum. Genet. 2003;113:268–275. doi: 10.1007/s00439-003-0970-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vaché C., Besnard T., le Berre P., García-García G., Baux D., Larrieu L., Abadie C., Blanchet C., Bolz H.J., Millan J. Usher syndrome type 2 caused by activation of an USH2A pseudoexon: implications for diagnosis and therapy. Hum. Mutat. 2012;33:104–108. doi: 10.1002/humu.21634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rio Frio T., McGee T.L., Wade N.M., Iseli C., Beckmann J.S., Berson E.L., Rivolta C. A single-base substitution within an intronic repetitive element causes dominant retinitis pigmentosa with reduced penetrance. Hum. Mutat. 2009;30:1340–1347. doi: 10.1002/humu.21071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Naruto T., Okamoto N., Masuda K., Endo T., Hatsukawa Y., Kohmoto T., Imoto I. Deep intronic GPR143 mutation in a Japanese family with ocular albinism. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:11334. doi: 10.1038/srep11334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mayer A.K., Rohrschneider K., Strom T.M., Glöckle N., Kohl S., Wissinger B., Weisschuh N. Homozygosity mapping and whole-genome sequencing reveals a deep intronic PROM1 mutation causing cone-rod dystrophy by pseudoexon activation. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2016;24:459–462. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2015.144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liquori A., Vaché C., Baux D., Blanchet C., Hamel C., Malcolm S., Koenig M., Claustres M., Roux A.F. Whole USH2A gene sequencing identifies several new deep intronic mutations. Hum. Mutat. 2016;37:184–193. doi: 10.1002/humu.22926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Carss K.J., Arno G., Erwood M., Stephens J., Sanchis-Juan A., Hull S., Megy K., Grozeva D., Dewhurst E., Malka S., NIHR-BioResource Rare Diseases Consortium Comprehensive rare variant analysis via whole-genome sequencing to determine the molecular pathology of inherited retinal disease. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2017;100:75–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gardner J.C., Liew G., Quan Y.H., Ermetal B., Ueyama H., Davidson A.E., Schwarz N., Kanuga N., Chana R., Maher E.R. Three different cone opsin gene array mutational mechanisms with genotype-phenotype correlation and functional investigation of cone opsin variants. Hum. Mutat. 2014;35:1354–1362. doi: 10.1002/humu.22679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ueyama H., Muraki-Oda S., Yamade S., Tanabe S., Yamashita T., Shichida Y., Ogita H. Unique haplotype in exon 3 of cone opsin mRNA affects splicing of its precursor, leading to congenital color vision defect. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2012;424:152–157. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.06.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gardner J.C., Webb T.R., Kanuga N., Robson A.G., Holder G.E., Stockman A., Ripamonti C., Ebenezer N.D., Ogun O., Devery S. X-linked cone dystrophy caused by mutation of the red and green cone opsins. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2010;87:26–39. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sangermano R., Khan M., Cornelis S.S., Richelle V., Albert S., Garanto A., Elmelik D., Qamar R., Lugtenberg D., van den Born L.I. ABCA4 midigenes reveal the full splice spectrum of all reported noncanonical splice site variants in Stargardt disease. Genome Res. 2018;28:100–110. doi: 10.1101/gr.226621.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gérard X., Perrault I., Munnich A., Kaplan J., Rozet J.M. Intravitreal injection of splice-switching oligonucleotides to manipulate splicing in retinal cells. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids. 2015;4:e250. doi: 10.1038/mtna.2015.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Murray S.F., Jazayeri A., Matthes M.T., Yasumura D., Yang H., Peralta R., Watt A., Freier S., Hung G., Adamson P.S. Allele-specific inhibition of rhodopsin with an antisense oligonucleotide slows photoreceptor cell degeneration. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2015;56:6362–6375. doi: 10.1167/iovs.15-16400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Roehr B. Fomivirsen approved for CMV retinitis. J. Int. Assoc. Physicians AIDS Care. 1998;4:14–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.