Abstract

Despite the rapid discovery of genes for rare genetic disorders, we continue to encounter individuals presenting with syndromic manifestations. Here, we have studied four affected people in three families presenting with cholestasis, congenital diarrhea, impaired hearing, and bone fragility. Whole-exome sequencing of all affected individuals and their parents identified biallelic mutations in Unc-45 Myosin Chaperone A (UNC45A) as a likely driver for this disorder. Subsequent in vitro and in vivo functional studies of the candidate gene indicated a loss-of-function paradigm, wherein mutations attenuated or abolished protein activity with concomitant defects in gut development and function.

Keywords: GCUNC-45

Introduction

The association of congenital diarrhea and hereditary cholestasis in childhood and infancy is rare, and many individuals remain genetically undiagnosed. Recently, some genes identified in one clinical presentation have been expanded to other clinical features. As an example, compound heterozygous and homozygous variants in myosin VB (MYO5B [MIM: 606540]) have been identified as a cause of congenital diarrhea with microvillus inclusion disease (MVID [MIM: 251850]).1 Cholestasis, reported as an atypical presentation in MVID, has been considered a side effect of parenteral nutrition. Next-generation sequencing approaches have been necessary to span the clinical spectrum to isolated cholestasis.2, 3 It has been shown that MYO5B, associated with plasma membrane recycling and transcytosis, is essential for polarization of hepatocytes, enterocytes, and respiratory epithelial cells.4, 5 This broadening of clinical spectra has been important for the demonstration that microvilli are markers of disorders in apical-membrane trafficking and assembly, from bowel to liver.6, 7 Such variable clinical presentations have also been demonstrated for other genes responsible for digestive and liver diseases, including ATP binding cassette subfamily B member 11 (ABCB11 [MIM: 603201]),8, 9 tetratricopeptide repeat domain 37 (TTC37 [MIM: 614589]), and Ski2 like RNA helicase (SKIV2L [MIM: 600478]).10, 11, 12 Here, we investigated four families presenting with a phenotypic constellation that includes cholestasis, congenital diarrhea, impaired hearing, and bone fragility. We were intrigued by the fact that, although several of the presenting features are also encountered in various genetic syndromes, we could not identify examples in the literature in which individuals shared all observed pathologies. Given these observations, we hypothesized that the constellation of phenotypes in the individuals in our study likely represents a clinical entity. To understand the genetic basis of this disorder and to provide an entry point toward both mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets, we studied four individuals from three families. By combining sequencing with functional studies of candidate genes in vitro and in vivo, we identified Unc-45 Myosin Chaperone A (UNC45A) as a driver for this disorder. UNC45A belongs to the UCS protein family (UNC-45/CRO1/She4p) and has not been linked to human genetic disorders. Notably, the C. elegans UNC-45 ortholog was first described in a screen for mutations causing motility disorders, a finding likely relevant to the etiopathology seen in humans.

Material and Methods

Whole-Exome Sequencing (WES)

We obtained written consent from parents under a protocol approved by each of our perspective institutional review boards. Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral-blood samples from the proband and both parents via standard procedures using the Gentra Puregene blood kit (QIAGEN). Family A samples were processed in Dijon University Hospital. The Biobank of the Department of Genetics of La Timone Hospital proceeded with the DNA extraction and ensured the long-term storage of samples from families B and C.

For all individuals (A.II.2, B.II.3, B.II.4, C.II.1, and their parents), whole-exome capture and sequencing were performed at Integragen platform (Integragen SA) from 1.5 μg of genomic DNA per individual using SureSelect Human All Exon V5 kit (Agilent). The resulting libraries were sequenced on a HiSeq 2000 (Illumina) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations for paired-end 75 bp reads. Reads were aligned to the human genome reference sequence (GRCh37/hg19 build of UCSC Genome Browser) with the Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (BWA, v.0.7.6a), and potential duplicate paired-end reads were marked with Picard v.1.109. The Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK) v.3.3-0 was used for base quality score recalibration, indel realignment, and variant discovery (both single-nucleotide variants and indels). Read mapping and variant calling were used for data analysis and interpretation. Variants were annotated with SeattleSeq SNP Annotation 138. Variants present at a frequency >1% in dbSNP 138 and the NHLBI GO Exome Sequencing Project or present from local exomes of unaffected individuals were excluded (see Web Resources). For the individual A, variants were filtered as described.13 For individuals B.II.3, B.II.4, and C.II.1, variants were filtered with the in-house Variant Analysis and filtration Tool software (VarAFT). Variant filtering followed the following criteria: variants affecting the coding sequence, including (1) splicing and (2) rare variants (<1% allele frequency) from public databases (see Web Resources), (3) homozygous, compound heterozygous, or de novo variants. The candidate variants in UNC45A were confirmed by Sanger sequencing on a 3500XL Genetic Analyzer (ThermoFisher).

Western Blotting

Fibroblasts of B.II.3 and all the individuals’ lymphoblastoid cells (A.II.2, B.II.3, B.II.4, and C.II.1) were lysed by NP40 cell lysis buffer (ThermoScientific) complemented with Halt Proteases and Phosphatases Inhibitor Cocktail 100X (ThermoScientific). After incubation on ice for 30 min, lysed cells were sonicated (4 cycles 15 s on/15 s off), then centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant was collected and analyzed for protein concentration by Pierce BCA Protein Assay (ThermoScientific). Whole lysates of fibroblasts and lymphoid cells (40 μg per lane) were loaded onto a SDS-PAGE 10% Bis-Tris gel (Bio-rad) for electrophoresis and transferred to a PVDF membrane. The membranes were hybridized with monoclonal mouse anti-human UNC45A antibody (1/1,000; ADI-SRA-1800, Enzo Life Sciences) and with Rabbit anti-human Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase polyclonal Antibody (1/10,000) (as loading control; Flarebio Biotech).

In vivo Zebrafish Assays

All animal work was performed with approved protocols from Duke’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. To determine the effect of unc45a suppression in zebrafish, we designed a splice blocking morpholino (MO) against exon 3 of the zebrafish unc45a (ENSDART00000159409.1). To assess efficiency of the MO, we extracted total RNA from control and MO-injected embryos and performed RT-PCR across the site targeted by the MO, followed by sequencing of the RT-PCR products. For the rescue experiments, we in vitro transcribed human WT and V423N-encoding mRNA using the SP6 mMessage mMachine kit (Ambion). All injections were done at the 1- to 4-cell stage and each experiment was performed in triplicate as described.14

Fluorescent microsphere gavage was performed on 5 dpf zebrafish anesthetized in tricaine and mounted in 3% methylcellulose. Injection of Fluoresbrite polychromatic red 2.0 micron microspheres (Polysciences #19508) was gavaged into the zebrafish intestinal lumen as described.15 Brightfield and gavage images were taken of 5 dpf embryos using the Nikon AZ100 microscope with a 2× objective and a 5.0-megapixel DS-Fi1 digital camera as previously described.16

Serial sections of the zebrafish were obtained by mounting in 3% low-melting point agarose and sections on a vibratome. Standard immunohistochemistry was performed using Phalloidin and 4e8 (both used at 1:1,000 dilution). Sections were mounted onto a coverslip using vectashield and imaged on a Nikon Eclipse 90i with a C2-SH camera at 20×. Image analyses and statistics were performed as previously described.17

Results

Clinical Report

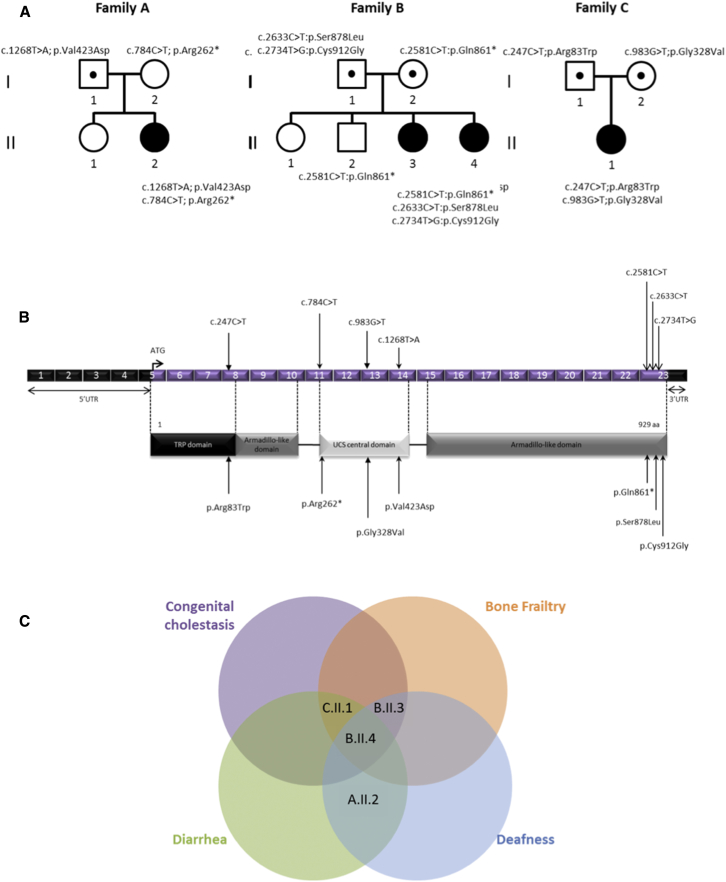

All four probands share multiple clinical symptoms including congenital cholestasis, diarrhea, bone fragility with recurrent fractures, and deafness (Figure 1; see detailed clinical report in Supplemental Note). They were assembled together after the discovery of independent homozygous or compound heterozygous variants of UNC45A, following a genotype-first approach.

Figure 1.

UNC45A Variants and Gene Structure

(A) Pedigrees of the three families with mutations in UNC45A.

(B) Structural organization of UNC45A transcript (Ensembl: ENST00000394275) and protein with known conserved protein domains and localization of amino acid residues affected by mutations identified in the three families. Exonic (in purple) regions are not drawn to scale.

(C) Venn diagram showing the overlap between clinical signs of the four individuals.

Family A

The proband is a 5-year-old girl of European descent, the second child of unrelated parents with no family history of digestive disease. She presented intractable diarrhea requiring parenteral nutrition since her fourth day of life. Her evolution was marked by language delay partially linked to severe bilateral perception deafness; she still has parenteral nutrition. To date, there is no sign of bone fragility or of liver disease.

Family B

Two probands are siblings from unrelated parents, originating from Tunisia. There was no known family history of the clinical presentation observed in the two probands. They have one sister and one brother, both of whom are healthy and have normal height. CGH array did not detect any chromosome rearrangements and targeted sequencing of known disease genes did not reveal any candidate pathogenic variants.

Individual B.II.3, currently 23 years old, presented at 15 days of life with icteric cholestasis with normal GGT level. Icterus disappeared at 2.5 years but elevated levels of bile acid associated with intractable pruritus remained, leading to partial internal biliary diversion at the age of 19 allowing an amelioration of the pruritus. She presented bone fragility: 23 fractures with normal levels of PTH and vitamin D. Severe bilateral perception deafness was diagnosed in her fifth year. She presented a failure to thrive with a current weight of 38.5 kg and height of 147.5 cm and a slight intellectual disability. (See full report in Supplemental Note.)

Individual B.II.4, currently 18 years old, presented an icteric cholestasis with elevated GGT at 7 days of life. Like her sister, icterus resolved at 3 years, but cholestasis with elevated level of GGT remained as well as elevated levels of bile acid associated with intractable pruritus. These issues led to partial internal biliary diversion at the age of 12, allowing an amelioration of the pruritus. She had bone fragility with multiple fractures and osteonecrosis of the femoral head at the age of 14, secondary to left hip dysplasia at birth and normal calcium phosphate, D vitamin, and PTH levels. Perception deafness was discovered in her teens. Initially, she presented diarrhea requiring parenteral and enteral nutrition. Diarrhea resolved with time, but a failure to thrive persisted at the last evaluation with a weight of 38.5 kg (−3 SD) and a height of 147.5 cm (−2.5 SD) and a mild intellectual disability was noted like her sister.

Family C

The proband is a 5-year-old female born to unrelated parents of Turkish origin. After 15 days of life, the proband presented with cholestatic icterus with normal level of GGT associated with liver failure; both resolved at 4 months of life. She presented bone fragility with two spontaneous fractures, with normal calcium phosphate, PTH, and D vitamin levels. She had diarrhea since the age of 2 months, requiring parenteral nutrition. She continues to have parenteral nutrition and has had recurrent episodes of cytolysis.

Whole-Exome Sequencing of Family A and B Identified Variants in UNC45A

We adopted a genetic approach for the study of a case of intractable diarrhea. The simplex case subject in family A was found in a large cohort of individuals without genetics diagnosis. This study was part of an “undiagnosed program” focusing on the identification of the genetic basis of pathologies in more than 500 affected individuals.

The exome sequencing of this family was first analyzed following a trio strategy. The autosomal-dominant de novo hypothesis first allowed the identification of a de novo variant in UNC45A: c.784C>T (p.Arg262∗) encoding a nonsense allele (the RefSeq accession number GenBank: NM_001039675.1 and the transcript ID Ensembl: ENST00000394275.6 was used to name the UNC45A mutations).

A second analysis under the autosomal-recessive hypothesis identified nine genes with homozygous or compound heterozygous variants in their coding region.UNC45A and CLRN2 (clarin 2) were considered the strongest candidates: neither has been associated to date with a clinical phenotype in human disease. Among the remaining genes, two have been associated with a human pathology: FRAS1 (MIM: 607830; phenotype MIM: 136680) and MYO15A (MIM: 602666; phenotype MIM: 600316). Frasier syndrome (MIM: 136680) can be likely excluded due to the divergent clinical presentation, while MYO15A formally remains a candidate for the deafness phenotype of the individual. However, there are no functional clues about the variant in MYO15A, which is thus classified as a variant of unknown significance (VUS). Sanger sequencing for the discovered UNC45A mutations confirmed that the missense variant c.1268T>A (p.Val423Asp) was inherited from the father and the stop-gained mutation was de novo (compound heterozygous status).

Independently, we performed whole-exome sequencing on genomic DNA from individual B.II.3 and B.II.4 and their parents B.I.1 and B.I.2 (family B; Figure 1). The trio-based analysis did not identify likely clinically relevant variants in known disease-associated genes. Under the hypothesis of either an autosomal-recessive or de novo dominant mode of transmission, a search for homozygous, compound heterozygous, or de novo rare variants (<0.1% in ExAC Browser and GnomAD) allowed us to identify a unique mutated gene shared by the two sisters: UNC45A, a locus not yet associated with any known human genetic disorder. Our exome findings and the high predicted expression levels of UNC45A in bone, colon, and liver (Proteomics DB) rendered this locus a strong candidate. The three identified UNC45A variants were confirmed by Sanger sequencing and their segregation was consistent with an autosomal-recessive trait (Figure 1). The two missense c.2633C>T (p.Ser878Leu) and c.2734 (p.Cys912Gly) mutations and the nonsense c.2584C>T (p.Gln861∗) mutation are all predicted to be damaging by UMD Predictor.18, 19 They are not found in gnomAD database, except for the variant c.2633C>T (p.Ser878Leu) which is reported seven times in the heterozygous state (7/277,162).

Biallelic UNC45A variants were the only sites shared among the two unrelated families with overlapping phenotypic features, thereby bolstering our interest for a likely causal association of UNC45A variants with the disease presentation.

Additional Families with Phenotypic Match: Discovery of Family C

We added UNC45A to our candidate gene list and we reanalyzed the exomes of families without molecular diagnosis with phenotypes similar to those exhibited by individuals of families A and B. We identified two missense mutations in a third unrelated family presenting liver disease and bone fragility. Specifically, in family C, we identified two missense mutations—c. 247C>T (p.Arg83Trp) and c.983G>T (p.Gly328Val)—in UNC45A (Figure 1). These substitutions are predicted to be damaging; one is found only four times (frequency of 4/276,948) in heterozygotes, whereas the second one has never been reported in gnomAD Browser. Given the overlap of clinical features of individual C.II.1 with the clinical spectrum of the other individuals described here, these results provided further evidence for a causal association of biallelic UNC45A mutations with this phenotypic presentation.

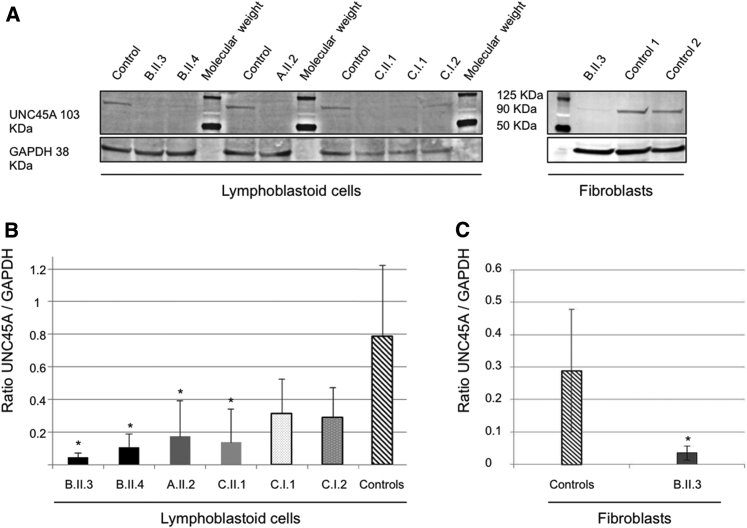

Functional Impact of Variants Found in UNC45A on Protein Level

To investigate whether these alleles have an effect on protein abundance, we performed western blot using a monoclonal antibody against UNC45A in all the lymphoblastoid cell lines available in our cohort. We detected UNC45A at the predicted size of 103 kDa; quantification of the observed signal in each individual (and the parents of the individual C.II.1) showed a decrease of UNC45A abundance across all individuals’ lymphoblastoid cells. Specifically, a significant decrease of protein abundance in each of A.II.2, B.II.3, B.II.4, and C.II.1 (80%, 93%, 89%, and 70% decrease, respectively) compared to control cells (Figures 2C and 2D). Furthermore, we did not detect any signal at ∼95 kDa, which would have corresponded to the truncated protein translated from the UNC45A allele carrying the nonsense mutation p.Gln861∗. The protein absence cannot be explained by NMD since the stop mutation occurs in the last exon of the gene but rather suggests the instability of the truncated protein.

Figure 2.

Western Blot Detection and Quantification of UNC45A Protein in Lymphoblastoid Cells and Fibroblasts

(A) Detection of UNC45A by western blot analysis in lymphoblastoid cells and fibroblasts using a monoclonal antibody. GAPDH was used as a loading control.

(B and C) Quantification of UNC45A protein levels with Fiji software shows significantly lowered levels of the expression of UNC45A in all individuals’ lymphoblastoid cells (B) and fibroblasts of individual A.II.3 (C). Values are mean ratio ± SD, n = 3; Welch’s two sample t test (affected individual versus control) (∗p < 0.04).

Regarding nonsense variant p.Arg262∗ in individual A, which maps to exon 11, we likewise did not detect any truncated protein (predicted size ∼30 kDa). In this case, due to the position of the stop mutation, NMD could explain this absence. However, the epitope recognized by the antibody remains unknown and could target the deleted part of the protein. Therefore, we cannot formally exclude the possibility of the existence of a truncated protein lacking its C-term part which is known to be critical for nonmuscle myosin II (NM-II) folding.20 Of note, in family C, the father C.I.1 (who is heterozygous for p.Arg83Trp) and the mother C.I.2 (who is heterozygous for p.Val423Asp) also had reduced UNC45A levels (45% and 52%, respectively), indicating that these alleles are also associated with reduced protein level and lead to the abrogation of protein stability. Together, all these studies suggest a loss of protein abundance/activity paradigm and thus a loss-of-function disorder.

We next asked whether the reduction of UNC45A levels was restricted to lymphoblastoid cells. Using whole-cell lysates from individual B.II.3 fibroblasts, we observed an 82% decrease of UNC45A compared to control cells (Figures 2A and 2C). Similar to the previous experiment, we could not detect any signal that might represent the truncated protein, again suggesting NMD. Quantification of the UNC45A mRNA produced in these cells was consistent with this notion; we observed a 40% and 50% decrease of transcripts levels in lymphoblastoid cells of individuals B.II.3 and B.II.4, respectively (Figure S3).

In Vivo Functional Testing of the UNC45A Variation in Zebrafish

With the identification of UNC45A likely loss-of-function mutations in affected individuals, we next sought to ask whether dysfunction of this gene contributes to experimentally tractable aspects of the phenotype. We have shown previously the utility of the zebrafish system to assess the involvement of genetic lesions in the formation and function of the gut.14, 21, 22 The zebrafish locus is predicted to encode three splice isoforms of unc45a; we focused our studies on the canonical (longest) isoform (ENSDART00000159409.1), which is 64% identical to human UNC45A (ENSG00000140553); the other two isoforms are shorter (230 aa and 218 aa versus 935 aa for the canonical isoform) (Figures S8 and S9). We designed a MO against the splice donor site of zebrafish unc45a exon 3. This resulted in the inclusion of intron 3, leading to a premature stop.

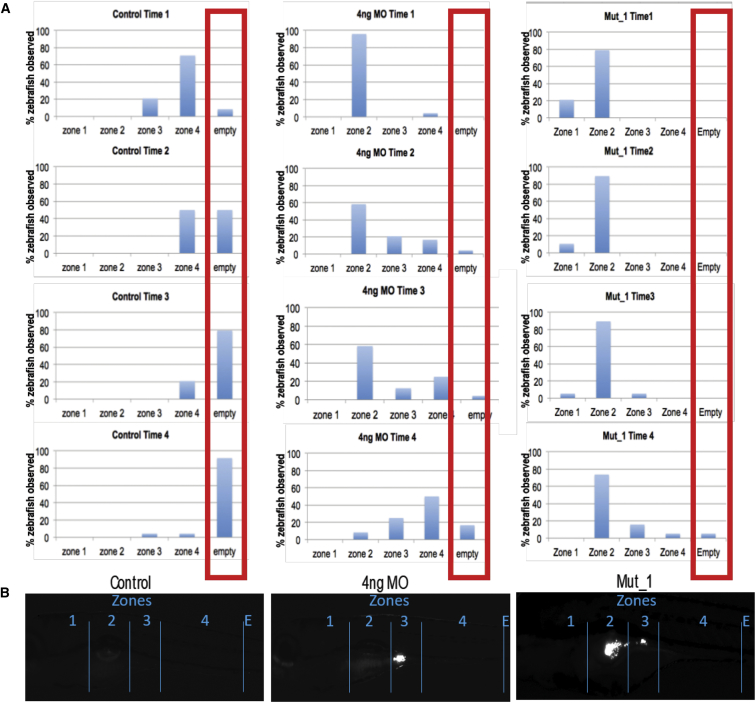

To assess one of the primary clinical phenotypes of the affected individuals, congenital diarrhea, we tested the effects of suppression of unc45a on both enteric neurons and intestinal motility. We first asked whether this phenotype could be caused by a neurodevelopmental enteric defect. We therefore visualized and counted the neurons along the zebrafish gut by staining with antibodies against HuC/D. In triplicate experiments performed blind to injection cocktail, we could not detect any appreciable difference in the number of enteric neurons in morphants versus controls, suggesting that unc45a suppression does not impact neurodevelopment in the gut (Figure S10). Next, we assayed intestinal motility by fluorescent microsphere gavage into the anterior intestine of 5 dpf (days post fertilization) embryos,15, 16 followed by recording of the rate of intestinal motility of the microspheres as a function of time (imaging at 0, 3, 6, 9, and 24 hr). At each time point, we scored in which intestinal zone (1–4, based on anatomical landmarks) the fluorescent microspheres were located as a measurement of transit through the intestine post-gavage. Performing ordinal logistic regression and repeated-measures analysis, we saw that, as time progresses, control larvae are less likely to have microspheres remaining in their intestinal lumen compared to morphants (p < 0.0001; OR = 0.504), with a majority of morphants having microspheres remaining in their intestine at 24 hr after gavage. These data suggest that suppression of unc45a leads to an intestinal motility defect (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Microgavage Assay to Assess Intestinal Motility

Fluorescent microspheres were gavaged and their transit was observed at 0, 3, 6, 9, and 24 hr in unc45 morphants and mutants.

(A) Numbers of embryos with observed fluorescence in the four zones of the alimentary canal at four different time points. Compared to controls (left set), in which fluorescent beads peak in zone 4 at time 1 and the progressively expelled from the gut (times 2–4). Both morphants (middle set) and mutants (right set) show presence of fluorescent beads in zones 1 and 2 of the gut.

(B) Representative images of the gut from controls, morphants, and mutants, demarcating the four zones and showing characteristic evidence of GFP in zones 2 and 3.

To test this observation further, we turned our attention to a stable genetic model. We obtained the kurzschlusstr12 (kustr12) zebrafish mutant, an aortic arch mutant identified previously in a forward genetic screen caused by a nonsense mutation in unc45a.23 Although gut motility phenotypes had not been reported previously, such phenotypes are not readily observable; we therefore tested mutants directly by gavage of fluorescent pellets, followed by measurement of the clearance efficiency of these along the alimentary canal as a function of time. Specifically, we divided the gut into four anatomically defined zones and we measured the proportion of embryos that had GFP present in each zone. Consistent with the intestinal phenotype observed in most of our probands, kustr12 mutants had a significant delay in clearing fluorescence that was even more pronounced than what we observed in our morphants. Repeated-measures analysis showed that as time progresses, control larvae are less likely to have microspheres in their intestinal lumen (the majority had no microspheres in their intestines) compared to kustr12 fish (p = 0.0009; OR = 0.1387) with the majority of the microspheres in the kustr12 larvae remaining in zone 2 (compared to morphants that showed accumulations primarily in zones 3 and 4 (Figure 3). The observed motility defect was not due to dysfunctional peristalsis, as there was no appreciable peristalsis defect in kustr12 mutants.

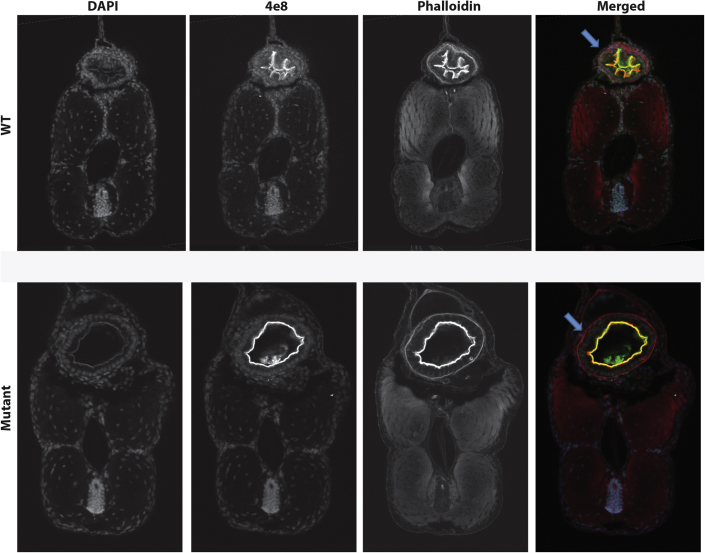

We next asked whether the intestinal motility defect could be linked to structural defects. Analysis of peristaltic movement did not show any appreciable differences between WT and mutant larvae (Movie S1), suggesting that a gross defect of the musculature is unlikely. However, observations of control and mutant animals under brightfield showed a lack of folds in the intestine of kustr12 fish. We therefore performed serial sections and used markers for F-actin (Phalloidin) and intestinal brush borders (4e8) to determine whether the defects in intestinal motility we observe in the mutant larvae were the result of structural abnormalities. Analysis of kustr12 mutant and control serial sections revealed defects in the structure of zones 2 and 3 of kustr12 animals (Figure 4). Staining with Phalloidin revealed that, as opposed to having the expected epithelial folds lining the lumen, kustr12 mutant intestinal tubes are devoid of folds in zones 2 and 3, corresponding to the anterior intestine. The differences in structure were restricted to, and specific for, zones 2 and 3; there were no structural differences in zone 4 and no brush border defects observed in the kustr12 embryos, as their enterocytes maintained the expression and localization of 4e8, the absorptive cell marker.

Figure 4.

Histological Study of Transverse Sections of Zones 2 and 3 of 5 dpf Zebrafish

Markers for F-actin (Phalloidin) and intestinal brush borders (4e8) were used and revealed defects (lack of epithelial folds in the intestinal tube) in the structure of kustr12 larvae compared to controls.

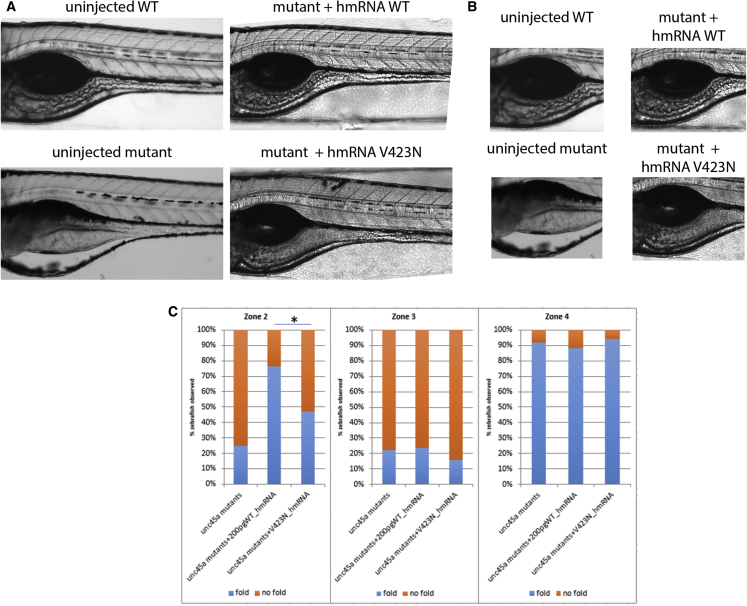

Given these phenotypes, we proceeded to test the functionality of the alleles discovered in our cohort. In family A, the proband was a compound heterozygote for p.Arg262∗ and p.Val423Asp, the first mutation being considered to encode a null allele. We therefore modeled c.1268T>A (p.Val423Asp). To reduce the phenotypic variability that we have sometimes found in morphants, we focused our studies on the of kustr12 homozygous mutants. Specifically, we injected both human wild-type (WT) and c.1268T>A (p.Val423Asp) encoding mRNA into kustr12 embryos at the 1- to 4-cell stage and we assessed their ability to improve the structural phenotypes observed in zone 2 of 5 dpf mutant guts. Injection of WT human mRNA was able to ameliorate the observed fold defects. In contrast, human c.1268T>A (p.Val423Asp) mRNA-injected kustr12 larvae were 3.44 times more likely to have no folds in zone 2 than kustr12 mutants injected with WT mRNA (Figure 5, p = 0.005; OR = 3.441), with modest overall amelioration of the mutant phenotype. Human WT mRNA was unable to rescue zone 3, likely because it forms somewhat later in development, at which point the injected mRNA is mostly extinguished, while zone 4 gave no pathology in mutants and therefore served as an indirect quality control for specificity. Taken together, these data suggested that UNC45A plays a role in the development of a functional intestinal system and that the UNC45A variant c.1268T>A identified in family A likely results in minimal (but not fully extinguished) UNC45A activity.

Figure 5.

Assessment of Human UNC45A c.1268T>A, Resulting in a p.Val423Asp Change (V423N), on Zones 2 and 3 of Mutant unc45a Zebrafishes

Mutant embryos were injected with either WT or V423N-encoding mRNA and intestinal folds were observed using brightfield microscopy. Mutants injected with WT encoding mRNA were able to restore folds in zones 2 and 3, but those injected with V423N-encoding mRNA were not restored, illustrating that V423N is pathogenic.

Discussion

We report a constellation of phenotypes that we propose to represent a distinct clinical entity, osteo-oto-hepato-enteric syndrome (O2HE). The main clinical features of O2HE syndrome include congenital diarrhea, congenital cholestasis, bone fragility, and deafness. In our families’ exomes, no mutations were found in genes previously known to be involved in cholestasis, brittle bones, or chronic diarrhea. Together, our in vitro and in vivo data provide strong evidence that loss of UNC45A function results in a clinical pathology, which includes loss of normal digestive intestinal transit.

Based on current knowledge, there is no obvious link between the clinical expression observed in the affected individuals in the three families and UNC45A function. Most studies of unc45 have been performed in Caenorhabditis elegans. However, invertebrates have a single unc-45 gene that is expressed in both muscle and non-muscle tissues, whereas vertebrates possess one gene expressed in striated muscle (UNC45B) and another that is expressed more ubiquitously (UNC45A). In fact, the phylogeny of UNC-45 homologs showed that this protein family appeared in the Holozoa lineage (Figure S4) and has undergone a duplication event in an ancestor of vertebrates. This event allowed the specialization of the two resulting paralogs: the muscle Unc45B and ubiquitous Unc45A. This divergence might explain the absence of skeletal muscle pathology in the three families studied here, although additional affected individuals will be required to define the full range of the clinical pathologies associated with UNC45A mutations in humans.

UNC45A belongs to the UCS protein family (UNC-45/CRO1/She4p). C. elegans unc-45 was first described after a screening for mutations causing motility disorders (UNC stands for uncoordinated).24 The UNC-45 protein has three recognizable domains: an N-terminal tetratricopeptide repeat (TRP) domain (∼115 amino acids), a central domain of ∼400 amino acids, and a C-terminal UCS domain (∼400 amino acids).24, 25 The TPR domain participates in protein-protein interactions, especially with Hsp70 (HSPA1A) and Hsp90 HSP90AA1.26 The role of the central domain remains unclear, while the C-terminal UCS domain is critical for myosin binding.25 Whether or not variants located within specific domains of UNC45A lead to different functional outcomes is still unknown. UNC45A appears to be ubiquitously expressed and has been postulated to be involved in cytoskeletal functions, such as cell division or exocytosis.27, 28 These data are consistent with the multi-organ defects observed in our affected individuals, as well as the structural pathology in the gut of our zebrafish mutants. However, other features of the protein are not reflected in the phenotype seen in humans. For example, UNC45A co-localizes with type II muscle myosin heavy chain B as well as type V myosins and plays an essential role in myoblast fusion and cell proliferation.29, 30, 31, 32 However, none of our affected individuals present muscular alterations, none have muscle weakness, and all present normal creatine phosphokinase level. Recently, in vivo studies have reported that unc45a plays a role in aortic arch development and could be one underlying cause of human vessel malformations.23 This, coupled to reports that individuals with visceral arteriovenous malformations can be more susceptible to cholestasis,33 makes UNC45A an attractive candidate; however, none of the people in our study display vessel malformation. Although this might be due to differences in development and physiology between lower organisms and humans, we favor the hypothesis in which minimal activity of the human alleles (in contrast to null homozygous zebrafish embryos) might protect from this pathology. Moreover, even if the link between the observed transit time delay in zebrafish and congenital diarrhea disease is not obvious, prolonged intestinal transit and diarrhea have been already observed in the familial GUCY2C diarrhea syndrome (FGDS), a rare autosomal-dominant inherited disease.34 More studies are needed to fully understand the physio pathological basis of the diarrhea in O2HE.

The identification of additional mutations at this locus will help clarify these questions.

There is a core phenotype in O2HE syndrome: four main signs seen in at least three individuals (Figure 1C). Phenotypic variability is observed in the three families studied here; however, this is seen in other congenital diseases (for example microvillus inclusion disease or tricho-hepato-enteric syndrome) and is expected in such complex diseases. The four individuals present some degree of developmental delay but we can’t exclude that it is a non-specific symptom. Indeed, in the individuals A.II.2, B.II.3, and B.II.4, the delay could be a secondary effect of the deafness. There are also some isolated signs, such as the tubulopathy and poor glycemic regulation found in individual C.II.1 and the hydrocephalus-related to stenosis of the aqueduct of Sylvius and the vesico-ureteral reflux found in individual B.II.4. It remains unclear whether these isolated signs are related to UNC45A or not. The clinical heterogeneity could reflect differing degrees of functional deficiency resulting from distinct effects of each mutation on UNC45A expression/stability on different tissues. Although we observe similar protein levels in lymphoblastoid cells, we cannot exclude that the mutations could have a differential impact on specific tissues. We also do not have direct evidence that all the mutations in the reported families undergo nonsense-mediated decay; further studies will be necessary to determine whether this mutational mechanism is ubiquitous. The variable expressivity could also be impacted by modifiers, epigenetics, or environmental factors.

In conclusion, our study finds a strong association between UNC45A loss-of-function mutations and a syndrome, we named osteo-oto-hepato-enteric (O2HE) syndrome. According to previous reports, UNC45A is possibly associated with the cytoskeleton and further evidence needs to be accumulated to understand the molecular mechanisms underlying the O2HE syndrome.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all the affected individuals and their families who participated in this study. We would like to thank Beth Roman for sharing the kurzschlusstr12 zebrafish, Jennifer Bagwell and Michel Bagnat for their expert advice on intestinal phenotyping and antibodies, and Melanie Garrett and Allison Ashley-Koch for their assistance with the statistical analysis of the zebrafish work. We also thank Erica Davis and Michael Mitchell for critical reading of the manuscript and helpful suggestions and Nathalie Colavolpe for her help with X-ray. This work was supported in part by grants from the Fondation Maladies Rares (WES20150601), AMGORE (Association Méditerranéenne pour les Greffes d’ORganes aux Enfants), the Regional Council of Burgundy (PARI 2014), the GFHGNP (Groupe Francophone d’Hépatologie-Gastroentérologie et Nutrition Pédiatriques, “Prix de recherche du Groupe Francophone d'Hépatologie, Gastro-entérologie et de Nutrition Pédiatriques 2015”), and the patient support group Association Romy - La vie par un fil.

Published: February 8, 2018

Footnotes

Supplemental Data include ten figures, two movies, and Supplemental Note (case reports) and can be found with this article online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2018.01.009.

Web Resources

1000 Genomes Browsers, http://www.internationalgenome.org/1000-genomes-browsers/

Ensembl Genome Browser, http://www.ensembl.org/index.html

ExAC Browser, http://exac.broadinstitute.org/

gnomAD Browser, http://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/

ImageJ Fiji, http://fiji.sc/Fiji

Mutalyzer, https://mutalyzer.nl/index

MutationTaster, http://www.mutationtaster.org/

OMIM, http://www.omim.org/

PolyPhen-2, http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/

UMD-Predictor, http://umd-predictor.eu/

VarAFT http://varaft.eu

Supplemental Data

We observed no defects in peristalsis in the kustr12 mutant compared to control.

References

- 1.Müller T., Hess M.W., Schiefermeier N., Pfaller K., Ebner H.L., Heinz-Erian P., Ponstingl H., Partsch J., Röllinghoff B., Köhler H. MYO5B mutations cause microvillus inclusion disease and disrupt epithelial cell polarity. Nat. Genet. 2008;40:1163–1165. doi: 10.1038/ng.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gonzales E., Taylor S.A., Davit-Spraul A., Thébaut A., Thomassin N., Guettier C., Whitington P.F., Jacquemin E. MYO5B mutations cause cholestasis with normal serum gamma-glutamyl transferase activity in children without microvillous inclusion disease. Hepatology. 2017;65:164–173. doi: 10.1002/hep.28779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Qiu Y.L., Gong J.Y., Feng J.Y., Wang R.X., Han J., Liu T., Lu Y., Li L.T., Zhang M.H., Sheps J.A. Defects in myosin VB are associated with a spectrum of previously undiagnosed low γ-glutamyltransferase cholestasis. Hepatology. 2017;65:1655–1669. doi: 10.1002/hep.29020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lapierre L.A., Kumar R., Hales C.M., Navarre J., Bhartur S.G., Burnette J.O., Provance D.W., Jr., Mercer J.A., Bähler M., Goldenring J.R. Myosin vb is associated with plasma membrane recycling systems. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2001;12:1843–1857. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.6.1843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hales C.M., Vaerman J.P., Goldenring J.R. Rab11 family interacting protein 2 associates with Myosin Vb and regulates plasma membrane recycling. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:50415–50421. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209270200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thompson R.J., Knisely A.S. Microvilli as markers of disordered apical-membrane trafficking and assembly: bowel and liver. Hepatology. 2014;60:34–36. doi: 10.1002/hep.27148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Girard M., Lacaille F., Verkarre V., Mategot R., Feldmann G., Grodet A., Sauvat F., Irtan S., Davit-Spraul A., Jacquemin E. MYO5B and bile salt export pump contribute to cholestatic liver disorder in microvillous inclusion disease. Hepatology. 2014;60:301–310. doi: 10.1002/hep.26974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davit-Spraul A., Fabre M., Branchereau S., Baussan C., Gonzales E., Stieger B., Bernard O., Jacquemin E. ATP8B1 and ABCB11 analysis in 62 children with normal gamma-glutamyl transferase progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis (PFIC): phenotypic differences between PFIC1 and PFIC2 and natural history. Hepatology. 2010;51:1645–1655. doi: 10.1002/hep.23539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pawlikowska L., Strautnieks S., Jankowska I., Czubkowski P., Emerick K., Antoniou A., Wanty C., Fischler B., Jacquemin E., Wali S. Differences in presentation and progression between severe FIC1 and BSEP deficiencies. J. Hepatol. 2010;53:170–178. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.01.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fabre A., Charroux B., Martinez-Vinson C., Roquelaure B., Odul E., Sayar E., Smith H., Colomb V., Andre N., Hugot J.P. SKIV2L mutations cause syndromic diarrhea, or trichohepatoenteric syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2012;90:689–692. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Monies D.M., Rahbeeni Z., Abouelhoda M., Naim E.A., Al-Younes B., Meyer B.F., Al-Mehaidib A. Expanding phenotypic and allelic heterogeneity of tricho-hepato-enteric syndrome. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2015;60:352–356. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rider N.L., Boisson B., Jyonouchi S., Hanson E.P., Rosenzweig S.D., Cassanova J.L., Orange J.S. Novel TTC37 mutations in a patient with immunodeficiency without diarrhea: extending the phenotype of trichohepatoenteric syndrome. Front Pediatr. 2015;3:2. doi: 10.3389/fped.2015.00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thevenon J., Milh M., Feillet F., St-Onge J., Duffourd Y., Jugé C., Roubertie A., Héron D., Mignot C., Raffo E. Mutations in SLC13A5 cause autosomal-recessive epileptic encephalopathy with seizure onset in the first days of life. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2014;95:113–120. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davis E.E., Frangakis S., Katsanis N. Interpreting human genetic variation with in vivo zebrafish assays. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2014;1842:1960–1970. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2014.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cocchiaro J.L., Rawls J.F. Microgavage of zebrafish larvae. J. Vis. Exp. 2013:e4434. doi: 10.3791/4434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bonora E., Bianco F., Cordeddu L., Bamshad M., Francescatto L., Dowless D., Stanghellini V., Cogliandro R.F., Lindberg G., Mungan Z. Mutations in RAD21 disrupt regulation of APOB in patients with chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:771–782.e11. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.12.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bainbridge M.N., Davis E.E., Choi W.Y., Dickson A., Martinez H.R., Wang M., Dinh H., Muzny D.M., Pignatelli R., Katsanis N. Loss of function mutations in NNT are associated with left ventricular noncompaction. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2015;8:544–552. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.115.001026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salgado D., Desvignes J.P., Rai G., Blanchard A., Miltgen M., Pinard A., Lévy N., Collod-Béroud G., Béroud C. UMD-Predictor: a high-throughput sequencing compliant system for pathogenicity prediction of any human cDNA substitution. Hum. Mutat. 2016;37:439–446. doi: 10.1002/humu.22965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frédéric M.Y., Lalande M., Boileau C., Hamroun D., Claustres M., Béroud C., Collod-Béroud G. UMD-predictor, a new prediction tool for nucleotide substitution pathogenicity -- application to four genes: FBN1, FBN2, TGFBR1, and TGFBR2. Hum. Mutat. 2009;30:952–959. doi: 10.1002/humu.20970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lehtimäki J.I., Fenix A.M., Kotila T.M., Balistreri G., Paavolainen L., Varjosalo M., Burnette D.T., Lappalainen P. UNC-45a promotes myosin folding and stress fiber assembly. J. Cell Biol. 2017;216:4053–4072. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201703107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sugathan A., Biagioli M., Golzio C., Erdin S., Blumenthal I., Manavalan P., Ragavendran A., Brand H., Lucente D., Miles J. CHD8 regulates neurodevelopmental pathways associated with autism spectrum disorder in neural progenitors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:E4468–E4477. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1405266111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bernier R., Golzio C., Xiong B., Stessman H.A., Coe B.P., Penn O., Witherspoon K., Gerdts J., Baker C., Vulto-van Silfhout A.T. Disruptive CHD8 mutations define a subtype of autism early in development. Cell. 2014;158:263–276. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anderson M.J., Pham V.N., Vogel A.M., Weinstein B.M., Roman B.L. Loss of unc45a precipitates arteriovenous shunting in the aortic arches. Dev. Biol. 2008;318:258–267. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Venolia L., Ao W., Kim S., Kim C., Pilgrim D. unc-45 gene of Caenorhabditis elegans encodes a muscle-specific tetratricopeptide repeat-containing protein. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton. 1999;42:163–177. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0169(1999)42:3<163::AID-CM1>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barral J.M., Bauer C.C., Ortiz I., Epstein H.F. Unc-45 mutations in Caenorhabditis elegans implicate a CRO1/She4p-like domain in myosin assembly. J. Cell Biol. 1998;143:1215–1225. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.5.1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scheufler C., Brinker A., Bourenkov G., Pegoraro S., Moroder L., Bartunik H., Hartl F.U., Moarefi I. Structure of TPR domain-peptide complexes: critical elements in the assembly of the Hsp70-Hsp90 multichaperone machine. Cell. 2000;101:199–210. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80830-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Price M.G., Landsverk M.L., Barral J.M., Epstein H.F. Two mammalian UNC-45 isoforms are related to distinct cytoskeletal and muscle-specific functions. J. Cell Sci. 2002;115:4013–4023. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Iizuka Y., Cichocki F., Sieben A., Sforza F., Karim R., Coughlin K., Isaksson Vogel R., Gavioli R., McCullar V., Lenvik T. UNC-45A is a nonmuscle myosin IIA chaperone required for NK cell cytotoxicity via control of lytic granule secretion. J. Immunol. 2015;195:4760–4770. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1500979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bazzaro M., Santillan A., Lin Z., Tang T., Lee M.K., Bristow R.E., Shih IeM., Roden R.B. Myosin II co-chaperone general cell UNC-45 overexpression is associated with ovarian cancer, rapid proliferation, and motility. Am. J. Pathol. 2007;171:1640–1649. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.070325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kachur T., Ao W., Berger J., Pilgrim D. Maternal UNC-45 is involved in cytokinesis and colocalizes with non-muscle myosin in the early Caenorhabditis elegans embryo. J. Cell Sci. 2004;117:5313–5321. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Venolia L., Waterston R.H. The unc-45 gene of Caenorhabditis elegans is an essential muscle-affecting gene with maternal expression. Genetics. 1990;126:345–353. doi: 10.1093/genetics/126.2.345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ao W., Pilgrim D. Caenorhabditis elegans UNC-45 is a component of muscle thick filaments and colocalizes with myosin heavy chain B, but not myosin heavy chain A. J. Cell Biol. 2000;148:375–384. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.2.375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lerut J., Orlando G., Adam R., Sabbà C., Pfitzmann R., Klempnauer J., Belghiti J., Pirenne J., Thevenot T., Hillert C., European Liver Transplant Association Liver transplantation for hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia: Report of the European liver transplant registry. Ann. Surg. 2006;244:854–862. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000247258.35406.a4. discussion 862–864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.von Volkmann H.L., Brønstad I., Gilja O.H., R Tronstad R., Sangnes D.A., Nortvedt R., Hausken T., Dimcevski G., Fiskerstrand T., Nylund K. Prolonged intestinal transit and diarrhea in patients with an activating GUCY2C mutation. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0185496. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0185496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

We observed no defects in peristalsis in the kustr12 mutant compared to control.