Abstract

Epigenetic mechanisms have rapidly and controversially emerged as silent modulators of host defenses that can lead to a more prominent immune response and shape the course of inflammation in the host. Thus, the epigenetics can both drive the production of specific inflammatory mediators and control the magnitude of the host response. The epigenetic actions that are predominantly shown to modulate the host defense against microbial pathogens are DNA methylation, histone modification and the activity of non-coding RNAs. There is also growing evidence that opportunistic chronic pathogens, such as Porphyromonas gingivalis, as a microbial host subversion strategy, can epigenetically interfere with the host DNA machinery for successful colonization. Similarly, the novel involvement of small molecule ‘danger signals’, which are released by stressed or infected cells, at the center of host–pathogen interplay and epigenetics is developing. In this review, we systematically examine the latest knowledge within the field of epigenetics in the context of host-derived danger molecule and purinergic signaling, with a particular focus on host microbial defenses and infection-driven chronic inflammation.

Keywords: epigenetics, danger molecule signaling, DNA methylation, histone deacetylation, opportunistic bacteria, innate immunity

The authors systematically examine the latest advances in the field of epigenetics in the context of host-derived danger molecules and purinergic signaling, with a particular focus on host microbial defenses and infection-driven chronic inflammation.

INTRODUCTION

Modulation of the host inflammatory response, in particular originating from receptor expression and production of inflammatory mediators, is tightly controlled at multiple levels. In these orchestrated cascades of events, epigenetic changes induced by aberrations in the host environment are gaining attention as fine regulators of specific immune signaling pathways, post-translational mRNA processing/protein secretion and access of transcription factors to immune gene promoters. Epigenetic modulation is characterized as the process of modifying a certain phenotype without changing the underlying DNA sequence. Accordingly, it has been proposed that epigenetic modifications such as changes in histone acetylation (Haberland, Montgomery and Olson 2009; Karouzakis et al.2009) may introduce heritable innate changes to the phenotype of host cells that in turn render them pro-inflammatory (Arbibe and Sansonetti 2007; Delcuve, Khan and Davie 2012; Drury and Chung 2015). There is also growing interest towards understanding the host–pathogen interaction with reference to epigenetic modifications. This specifically includes deciphering how certain opportunistic pathogens can evade the immune surveillance and cause sustained infection while others are rapidly cleared from the host body (Modak et al.2014). There are three well recognized epigenetic control mechanisms: DNA methylation, histone modification and the activity of non-coding RNAs, which embraces microRNAs, small interfering RNAs and long non-coding RNAs.

Packaging of genomic DNA in chromatin is a histone-dependent structural process that serves as a key mechanism in gene transcription regulation. Chromatin dynamics are arranged by chromatin-remodeling complexes and histone-modifying enzymes. Chromatin-remodeling complexes utilize adenosine triphosphate (ATP) hydrolysis to unwrap DNA and/or reposition nucleosomes allowing for the underlying DNA to become accessible or inaccessible for gene expression as well as DNA replication, repair or recombination (Hamon and Cossart 2008). When lysine amino groups are acetylated, the DNA becomes accessible for transcription. The balance of acetylation on the histones is governed by the activity of two enzymes: histone acetyltransferases (HATs) and histone deacetylases (HDACs), which, respectively, catalyze the acetylation of and removal of the acetyl groups from the amino groups of lysine residues (Berger 2007; B. Li, Carey and Workman 2007). Thus, the expression of inflammatory genes, DNA repair and cell proliferation have been shown to be controlled by the degree of acetylation of histone and non-histone proteins produced by these HATs and HDACs (Adcock 2007; Halili et al.2009; McKinsey 2011).

Epigenetic states can be commonly altered by environmental factors, which may subsequently lead to the development or progression of diseased phenotypes (Pang and Zhuang 2010). Among the most characterized epigenetic modifications is DNA methylation, which usually takes place at the C-5 position of the cytosine ring of DNA (5 mC), most commonly next to a guanosine (called the CpG island). The methylated CpG islands are found in non-coding regions of the genome associated with transcriptional repression. In this context, DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) are key enzymes responsible for catalyzing the transfer of methyl groups to cytosines in specific CpG structures. Methylation at previously unmethylated sites is catalyzed by a DNA (cytosine-5)-methyltransferase, such as DNMT3a/b, and is commonly maintained by DNMT1, referred to as maintenance methyltransferase. Together, these enzymes guarantee that a substantial part of the genome is often methylated, leaving only regulatory elements like promoters and enhancers, as well as CpG-rich islands, in an unmethylated state (Lindroth and Park 2013). The hypermethylation state of DNA at the promoter is predominantly associated with gene silencing. There is also evidence pointing to multiple epigenetic modifications, including DNA methylation and various histone modifications, that can work synergistically or antagonistically (Lindroth and Park 2013).

Epigenetic mechanisms involved in tumor development and cancer progression have already been widely explored (Yasmin et al.2015), and some potentially therapeutic drugs such as DNA methyltransferase inhibitors (Wong, Polly and Liu 2015) and histone deacetylase inhibitors (Krauze et al.2015) are currently being tested under clinical trials or are already in use on patients (X. Li et al.2015). However, the exact role of epigenetic events in host innate immune defenses and especially in the context of host–pathogen interaction is not yet well understood. A recent review presented the role of HAT and HDAC enzymes in controlling Toll-like receptors (TLRs), an important group of pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), in innate immunity. This work shed light on the putative involvements of DNA methylation and histone modification in recognition of pathogen associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) by TLRs and in TLR activation pathways (Hennessy and McKernan 2016). More specifically, the study demonstrated that methylation of certain CpG sites in the TLR2 promoter region is associated with active pulmonary tuberculosis or its phenotypes, probably through the down-regulation of TLR2 expression (Y. Chen et al.2014b). Interestingly, the group of Kinane et al. recently reported that TLR2 promoter hypermethylation can also be linked to microbial dysbiosis in an oral microenvironment (Benakanakere et al.2015). In this study, repeated sequential treatment of gingival epithelial cells with an oral pathogen, Porphyromonas gingivalis, promoted DNA methylation. In addition, increased DNA methylation was observed in gingiva from the experimentally induced periodontitis model using P. gingivalis-infected mice. The same study also demonstrated that tissues obtained from periodontitis patients exhibited differential TLR2 promoter methylation (Benakanakere et al.2015). Recently, another work demonstrated that activation of TLRs 1, 2 and 4 along with the nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain protein 1 (NOD1) by P. gingivalis lipopolysaccharide (LPS) but not by Escherichia coli LPS induced histone H3 acetylation in oral epithelial cells (Martins et al.2016). Taken together, these results highlight a new insight into epigenetic regulation by PAMPs while also highlighting the specificity of those PAMPs and host interplay that may contribute to chronic inflammatory conditions such as periodontal diseases.

Considering that damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), otherwise known as ‘danger signals’ (e.g. extracellular ATP (eATP) and high-mobility group protein B1 (HMGB1)), can exert similar control in cellular responses, especially in infection-driven inflammatory conditions associated with cell injury or stress, there is still little known on the exact mechanisms of epigenetic changes induced and potentially sustained by the danger signaling under such complex environments. It is becoming increasingly recognized that the interplay between PAMPs and DAMPs is critical to the type of immune reaction and magnitude of the immune response. There is some evidence that understanding the epigenetic pattern in disease progression may provide invaluable information for the diagnosis or prognosis and treatment of human chronic inflammatory diseases. In this regard, some studies have demonstrated epigenetic mechanisms to influence the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis (Horiuchi et al.2009; Hawtree et al.2015) or other chronic inflammatory models such as periodontal diseases (Cantley et al.2011, 2016) and it certainly seems a promising and rich territory to be explored in the coming years.

As a result of these recent findings, there is a compelling notion developing of how DAMPs could be involved in priming or education of the cells with which they interact. Crisan et al. postulated that innate immune memory can play a role in the pathogenesis of inflammatory diseases due to continual DAMP-induced functional reprogramming of immune cells, suggesting epigenetic regulation as an important possibility to be taken into account (Crisan, Netea and Joosten 2016). Accordingly, the DAMPs, especially the endogenous ‘danger signals’ such as eATP and HMGB1 that can be also associated with sterile inflammation and tissue damage, have lately been proposed as signaling molecules that can induce transcriptional functional alterations in immune cells via epigenetic changes. In this review, we systematically examine the latest evidence in the emerging field of epigenetics in the context of ‘danger signals’, especially extracellular nucleotide signaling, known as purinergic signaling, with a focus on infection-driven chronic inflammatory conditions.

EPIGENETIC STATUS IN INFECTION-DRIVEN INFLAMMATION

The trigger of innate immune system elements after recognition of pathogens results in expression of a number of genes to produce cytokines, chemokines and cell signaling pathways, as well as transcription factors, which are mostly well described. However, the epigenetic regulatory factors involved in the control of inflammatory gene expression still remain poorly explored. DNA methylation, histone modifications or even non-coding RNAs have recently been proposed to be critical mechanisms to fine-tune gene expression, and they are arising as key elements in cellular differentiation processes (Haberland, Montgomery and Olson 2009; Karouzakis et al.2009). In parallel, an interesting aspect that has been newly maturing is the epigenetic modifications induced by opportunistic pathogens (Hamon and Cossart 2008).

Specific alterations of host cellular machinery were reported to be mechanistically involved with chromatin remodeling and associated with coordination of exclusive gene expression patterns of the immune system. Wen et al. (2008) demonstrated that animals surviving severe peritonitis-induced sepsis, using a cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) model, had chronically deficient interleukin (IL) 12-producing dendritic cells. This was mechanistically explained by both trimethylation of lysine 4 residue of histone 3 (H3K4me3) and H3K27me2 at IL-12 promoters, which were related to gene activation and silencing, respectively. This study also indicated that alterations in histone methylation were involved in long-term aberrant gene expression patterns in dendritic cells and that these may likely contribute to the immunosuppression observed in post-sepsis animals and potentially in patients with severe sepsis (Wen et al.2008). In another study, the same group also showed that repressive histone methylation was present at promoter regions for the Th1 cytokine interferon (IFN)-γ and the Th2 transcription factor GATA-3 in CD4+ T cells from CLP mice. These results showed that CD4+ T-cell subsets from post-sepsis mice exhibit defects in activation and effector function, possibly due to chromatin remodeling proximal to genes involved in cytokine production or gene transcription (Carson et al.2010).

While it is still not completely resolved in the literature, a few studies indicate that reduced expression of HDACs in synovial tissue could contribute to the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis (Huber et al.2007; Maciejewska-Rodrigues et al.2010). However, another study from human monocytes and mice revealed that HDAC inhibitors can possess a potent anti-inflammatory effect that suppressed the production of cytokines induced by tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and LPS (Leoni et al.2002, 2005; Glauben et al.2006). Several reports have documented changes in HDAC activity in fibroblasts in the study model of rheumatoid arthritis and juvenile idiopathic arthritis, with recent studies showing a specific increase in HDAC1 activity (Horiuchi et al.2009; Kawabata et al.2010). Other researchers have also demonstrated anti-inflammatory effects of HDAC inhibitors in animal inflammatory models, vascular disease and cancer (Halili et al.2009; Iyer et al.2010; Tan et al.2010). HDAC activity was also correlated with the development and progression of some chronic diseases characterized by tissue fibrosis, such as chronic kidney disease, cardiac hypertrophy and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (Pang and Zhuang 2010).

As to the infections by opportunistic microbes, compelling evidence has shown that intracellular bacteria such as Anaplasma phagocytophilum (Garcia-Garcia et al.2009) and Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Hamon and Cossart 2008) can manipulate host cell epigenetics to achieve a successful course of infection. Mycobacterium tuberculosis, for example, was demonstrated to inhibit IFN-γ-induced expression of several immune genes through histone acetylation, which was suggested to be a possible mechanism for the long-term persistence in those chronic tuberculosis patients (Pennini et al.2006). The modulation of infectivity as well as latency through host epigenetic modifications also seems to be common among intracellular pathogens. In Toxoplasma gondii infection, histone acetylation was considered to be responsible for the switch between replicative and non-replicative stages of the pathogen (Dixon et al.2010). DNA methylation in the human fungal pathogen Candida albicans was shown to be related to the transition between its yeast and hyphal forms (Mishra, Baum and Carbon 2011). On the other hand, host epigenomic state can control microbial virulence by some intracellular pathogens (Gomez-Diaz et al.2012). This has been demonstrated in various experimental models in which host methylation status can cause damaging changes in microbial virulence factors, such as diminished bacterial envelope stability, reduced microbial motility, and impaired host invasion (Gomez-Diaz et al.2012).

Several recent studies highlighted the potential impact of the methylation pattern on the virulence of oral microorganisms, including the oral pathogen Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans. Eberhard et al. demonstrated that a methylation-deficient mutant strain of A. actinomycetemcomitans affected the epithelial immune response compared with the wild-type strain of the microorganism, indicating the biological importance of methylation for the interaction of pathogen with host. Their results specifically showed that a DNA-adenine-methyltransferase-deficient strain of A. actinomycetemcomitans (VT 1560) displayed reduced capacity to induce mRNA for the antimicrobial peptide human β-defensin-2 (hBD-2) and pro-inflammatory chemokine IL-8 compared with the wild-type strain. This attenuated phenotype was suggested to be due to its lacking bacterial DNA-adenine-methyltransferase activity. Furthermore, the same study demonstrated that the observed effect in the innate immune response was perhaps associated with the heterogeneity of the studied human epithelial cells since the cells derived from different donors responded in a different manner (Eberhard et al.2010). These findings emphasize the potential significance of epigenetic modifications in the host microbial pathogenesis.

Recently, Schliehe mechanistically demonstrated epigenetic regulatory processes can be involved in susceptibility to the bacterial infections that are secondary to influenza virus infection. In this work, they showed that type I interferons produced in response to viruses increase the expression of the host methyltransferase Setdb2, which mediates trimethylation of histone H3 Lys9 (H3K9) at the Cxcl1 promoter (Schliehe et al.2015). In the same study, Setdb2 deficiency resulted in exacerbated lung inflammation in a model of bacterial LPS-induced neutrophilia. This study was the first to demonstrate Setdb2 mediates influenza virus-induced susceptibility to superinfection with Streptococcus pneumoniae, highlighting that chromatin modifiers are increasingly observed as crucial effectors of immunoregulatory mechanisms (Schliehe et al.2015).

Interestingly, there is also correlational evidence linking the involvement of host microbiota and its interactions with dietary factors, focusing on the epigenetic processes affected by, and their influence on, human healthy and diseased states (Paul et al.2015). In a recent study, it was suggested that the type of food consumed modulates the composition of the gut microbiota and the metabolome they produce. The study specifically showed the epigenetic significance of the production of a number of low molecular mass bioactive substances such as folate, butyrate, biotin and acetate by the gut microbiome (Paul et al.2015). This production was linked to the ability of such microbiota to activate epigenetically silenced genes in cancer cells in response to dietary factors in the context of cancer prevention and therapy.

LINK BETWEEN EPIGENETIC MODIFICATIONS AND DANGER SIGNALING IN HOST INFLAMMATORY RESPONSE

The role of the danger signals, such as eATP, in deacetylation of histones has been investigated. Exogenous ATP treatment of host cells substantially and consistently enhanced the cleavage of H2A, H2B and H4 lysines by both non-nuclear HDAC1 and HDAC3 (C. Johnson et al.2002). This work showed that the ATP-dependent chaperone proteins, heat shock protein 60 (Hsp60) and heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70) were associated with non-nuclear HDAC complexes, providing persuasive evidence that the stimulatory effect of ATP on HDAC catalytic activity perhaps operates through these proteins (C. Johnson et al.2002). Regarding possible mechanisms by which ATP could augment the catalytic activity of HDAC complexes, Johnson et al. investigated whether HDAC activity was enhanced by ATP-dependent phosphorylation of one or more components of the complex by endogenous protein kinases (C. Johnson et al.2002). However, this hypothesis was not fully confirmed. Nevertheless, the study elegantly showed that cleavage of protein substrates required the action of ATP-dependent chaperone proteins Hsp60 and Hsp70, suggesting that these proteins were responsible for the observed effects of ATP on HDAC activity. In the same study, it was also demonstrated that both HDAC1 and HDAC3 immunocomplexes were maximally stimulated at or below the concentration of 0.1 mM ATP. Interestingly, the analog ATPγS, which is hydrolyzed much more slowly than ATP, provided only a small stimulation of deacetylation over the same concentration, further showing that the stimulatory effect requires rapid ATP hydrolysis (C. Johnson et al.2002).

It is well documented that both cytosolic and extracellular ATP concentrations (Ipata and Balestri 2013) as well as timing of ATP action in inflammatory microenvironment could be strongly dependent on the activity of ectonucleotidases (Morandini, Savio and Coutinho-Silva 2014a). Therefore, it is critical to understand the influence or participation of ATP-hydrolyzing host enzymes such as ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase-1 (ENTPD1, also known as CD39) and ecto-5′-nucleotidase (E5NT, also known as CD73) in epigenetic modulation of cellular events. Pharmacological inhibition of HDACs was shown to promote the differentiation of naive T cells towards a regulatory T cell (Treg) phenotype and this stimulation correlated with hyperacetylation of the histone H3 (Donas et al.2013). It was interesting that the role of ectoenzymes involved in the conversion of ATP to an immunosupressive adenosine (another host-derived danger molecule) was also investigated in this study. The results demonstrated the effect of pharmacological modulation of histone-modifying enzymes on the differentiation of Tregs. Moreover, this new phenotype that was generated in the presence of trichostatin A (TSA; a pan-HDAC inhibitor) has displayed phenotypical and functional differences from the Tregs generated in the absence of TSA. It was shown that TSA-generated CD4+Foxp3+ Tregs have increased suppressive activities. Briefly, the mean fluorescence of TSA-treated Tregs for the ectonucleotidases CD39 and CD73 showed a marked increase of 1.7- and 1.4-fold, respectively, suggesting that HDAC inhibition may affect the immune suppressive activity of Tregs by specifically increasing the protein levels of the ectonucleotidases CD39 and CD73 (Donas et al.2013).

A new study points to a possible cross-talk between ATP-cleavage enzymes, cell metabolism and epigenetic modulation (Hanover, Krause and Love 2012). The co-factors associated with the methylation and acetylation of epigenetic modifications of DNA and histones are being studied from various metabolic pathways, such as glycolysis. Glycolysis converts glucose to lactate with the concomitant production of ATP. Aerobic glycolysis is the primary metabolic pathway utilized by cancer cells and glycolytic enzymes are always greatly increased and/or deregulated in this situation (L. Chen et al.2014a). In this regard, endogenous intermediates of the glycolytic pathway such as fructose 1,6-bisphosphate (FBP) were reported to attenuate experimental arthritis by activating the anti-inflammatory adenosinergic pathway through the systemic generation of a danger molecule, extracellular adenosine, and subsequent activation of the purinergic adenosine receptor A2a (A2aR) (Veras et al.2015). In addition, this study mechanistically showed that FBP-induced adenosine generation required hydrolysis of eATP through activity of both CD39 and CD73 enzymes as the inhibition of these ATP-consuming enzymes abolished anti-arthritic effects of FBP (Veras et al.2015).

While the precise mechanisms by which epigenetic regulation such as through HDAC inhibition could influence inflammation in both chronic and acute inflammatory diseases remain poorly understood, some studies provide evidence for possible participation and regulation by purinergic signaling. The study by Carta et al. (2006) was the initial report to demonstrate that inhibition of HDACs did not affect the intracellular synthesis of pro-IL-1β precursor, but significantly reduced mature IL-1β secretion after activation of the purinergic P2X7 receptor by eATP. The binding of ATP to P2X7 receptor causes depolarization of the plasma membrane, cellular swelling and loss of cytoskeletal organization accompanied by formation of a non-selective pore, resulting in Ca2+ influx and K+ efflux (Solle et al.2001). These specific events are crucially recognized as key for inflammasome activation in cells of myeloid origin and subsequently required for pro-IL-1β processing and secretion (Morandini et al.2014b; Ramos-Junior et al.2015). The treatment of cells with P2X7 receptor antagonist can inhibit IL-1β secretion (Piccini et al.2008). Furthermore, recent studies conducted in non-myeloid cells such as human primary gingival epithelial cells infected with the oral pathogen P. gingivalis showed IL-1β release only if the host cells are subsequently stimulated with eATP, which couples with the P2X7 receptor on the host cell membrane (Yilmaz et al.2010).

Regarding the methylation status of this purinergic receptor, a recent study explored whether P2X7 receptor function is regulated by epigenetic alteration using two different cell lines, a non-cancerous primary human submandibular duct cell line and a human submandibular carcinoma cell line (Shin et al.2015). The study found that by treating the cells with a DNA demethylating agent, P2X7 receptor mRNA expression levels were increased in a time-dependent manner, suggesting that P2X7 receptor function is suppressed by hypermethylation of the P2X7 CpG island in non-cancerous salivary cell lines and also in normal human tissues. These results further imply that expression level and function of P2X7 receptor may be regulated by DNA methylation.

On the endogenous ‘danger signals’ and their involvement in the epigenetic modulation, El Gazzar et al. reported an interaction between the nuclear DAMP HMGB1, a pro-inflammatory danger molecule, and the linker histone H1 as essential components of the chromatin transcription silencing process for TNF-α during endotoxin tolerance (El Gazzar et al.2009). This finding highlighted HMGB1's possible role as an anti-inflammatory nuclear chromatin modulator. The repressive nature of HMGB1 and histone H1 was connected to methylation of H3K9 and promoter binding of the transcription factor and repressor, RelB. In a related study, the levels of acetylated HMGB1 increased with a concomitant decrease in total nuclear HDAC activity, suggesting that suppression of HDAC activity contributes to the increase in acetylated HMGB1 release after oxidative stress in hepatocytes (Evankovich et al.2010). This study also reported that silencing HDAC1 via RNA interference promoted HMGB1 translocation and release (Evankovich et al.2010). Interestingly, Johnson et al. recently demonstrated that eATP treatment induces HMGB1 release from uninfected human primary gingival epithelial cells, and that wild-type P. gingivalis infection is more effective than infection with a nucleoside diphosphate kinase (NDK)-deficient mutant strain of P. gingivalis in inhibiting eATP-induced HMGB1 release (L. Johnson et al.2015). Secreted NDKs are effector enzymes that can be used by opportunistic persistent bacteria, such as M. tuberculosis and P. gingivalis, to evade from the host immune system by depleting the danger molecule eATP via ATP hydrolysis. In addition, the same study observed a relocation of HMGB1 from the nucleus to the extracellular space, which was attenuated in cells treated with the upstream mediator of the canonical inflammasome pathway, caspase-1 inhibitor.

Accumulated evidence points to a role for epigenetic modulation for HDAC1 by the periodontal pathogen P. gingivalis (Imai, Ochiai and Okamoto 2009; Imai et al.2012). It produces high concentrations of butyric acid, which can act as a potent inhibitor of HDACs and cause histone acetylation. It was found that P. gingivalis could induce HIV-1 reactivation via chromatin modification and that secreted butyric acid, one of the bacterial metabolites, is responsible for this effect (Imai, Ochiai and Okamoto 2009). Reversible histone acetylation is a critical epigenetic regulator of chromatin structure and gene expression, in combination with other post-translational modifications. These patterns of histone modification are maintained by histone modifying enzymes such as HDAC1. In this context, it remains to be investigated whether and how P. gingivalis as well as other chronic-inflammation-related pathogens can interfere with host cell epigenetic mechanisms as a strategy to overthrow the immune response and propagate the infection.

Recently, Martins et al. (2016) described that oral epithelial cells from ligature-induced periodontitis mice had increased acetylation of histone H3. As mentioned previously, the same study showed that LPS from P. gingivalis or the heated-inactivated whole Fusobacterium nucleatum rapidly induced acetylation of histone H3 (15 min) when compared with LPS from E. coli (6 h) (Martins et al.2016). Furthermore, the study showed reduced levels of DNMT1 in response to LPS stimuli and activation of transcriptional coactivators, such as p300/CBP, which are known to be important for cell growth, differentiation and accumulation of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB). An earlier study also showed a decrease in DNMT1 and HDAC expression in gingival epithelial cells after incubation with live P. gingivalis and F. nucleatum (Yin and Chung 2011). However, the precise regulatory mechanisms regarding the interactions between DNMTs and HDACs with specific transcription factors remain to be further investigated. Although rather speculative, it is as yet undefined but possible that this mechanism is linked to an epigenetic change potentially caused by one of the bacterial secreted molecules, such as the ATP-cleavage enzyme NDK that is thought to be crucial for microbial adaptation in chronic host infection (Spooner and Yilmaz 2012). NDK of P. gingivalis has been shown to promote survival of human primary gingival epithelial cells by hydrolyzing eATP and preventing apoptosis mediated through P2X7 receptor activation (Yilmaz et al.2008; Choi et al.2013).

In other models of inflammation/tissue damage, such as in neuroimmune signaling (Zou and Crews 2014) during ischemia and reperfusion injury (Evankovich et al.2010), there is accumulating knowledge pointing to a link between HMGB1 release and decreased HDAC1 activity. However, in vivo studies demonstrating the functional relevance of epigenetic mechanisms in purinergic signaling-driven inflammation are still relatively scarce. At present, the best evidence to demonstrate that purinergic signaling is influenced by epigenetic status in a chronic inflammatory condition comes from an in vitro approach with cells under inhibition of certain histone deacetylases (Carta et al.2006). Recently, it was elegantly demonstrated that the combination of HDAC inhibition and LPS promotes the secretion of processed, bioactive IL-1β from dendritic cells and macrophages (Stammler et al.2015). This study showed that, in these cells, the IL-1β secretion pathway is caspase-1 independent, requires HDAC inhibition and is associated with cellular apoptosis. The existence of a new link between HDAC inhibition and a non-canonical caspase-8-dependent generation of bioactive IL-1β has also been raised lately, suggesting therapeutic applications for the development of HDAC-selective inhibitors with anti-inflammatory applications.

Another intriguing argument that warrants future studies is that among DAMPs one can also have cytosolic intracellular cytokines such as IL-1α, which was shown to be constitutively active and capable of signaling via the IL-1 receptor without requiring enzymatic cleavage (Kim et al.2013). This specific activity was also shown to mediate neutrophil recruitment upon hypoxia and IL-1α release from dying cells (Rider et al.2011). A previous study investigated the possibility that IL-1α could transduce signals from the nucleus to communicate chromatin damage to the surrounding tissue (Idan et al.2015). This work confirmed that DNA damage induced the secretion of IL-1α precursor and increased the levels of secreted IL-1α in cell supernatants after exposure to various DNA damaging agents. It was also shown that histone deacetylase inhibition by TSA reduced the secretion of the IL-1α precursor and of IL-6 from LPS-activated Raw 264.7 macrophages (Idan et al.2015). Another interesting investigation demonstrated cellular effects of HDAC inhibitors, including sodium butyrate, TSA and suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA) on cellular apoptosis (Amin, Saeed and Alkan 2001). In this study, it was shown that inhibition of HDAC induces significant apoptotic effects in leukemic cell lines. In addition, it was demonstrated that the caspase pathway was involved in the HDAC inhibitor-induced apoptosis as the study used non-specific broad-spectrum caspase inhibitors to demonstrate this effect. Neither Bcl-2 nor Bax, which are members of the B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL-2) family of regulator proteins, responsible from intrinsic apoptosis, appeared to be involved in this process. Instead HDAC inhibitors induced downregulation of the Daxx molecule, which is known to participate in Fas membrane receptor-induced apoptosis.

CONCLUDING REMARKS AND PERSPECTIVES

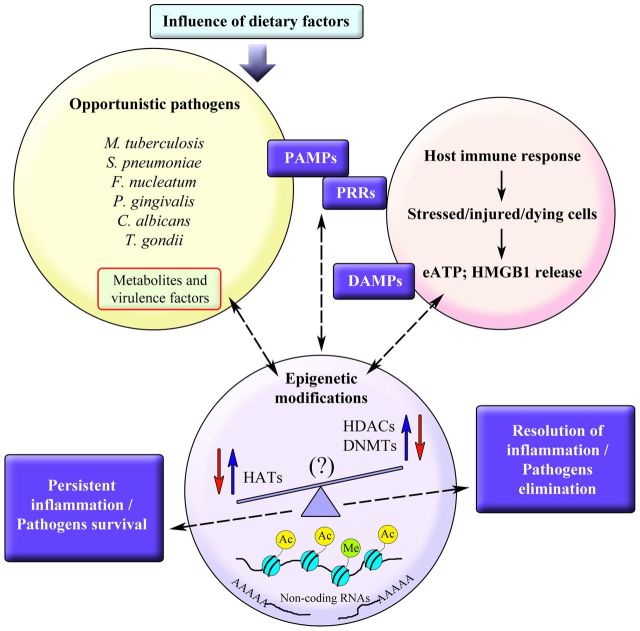

There is still much to understand about the putative mechanism(s) by which methylation, acetylation or the action of non-coding RNAs can affect the danger molecule–purinergic signaling axis for the fitness of host against microbial contenders or vice versa. Indeed, recent studies have started to reveal the breadth of epigenetic actions in changing host gene expression and controlling nucleotide signaling, both in healthy and disease situations. The relationship between extracellular nucleotide signaling and how epigenetic modifications prompted by colonizing pathogens can affect this purinergic signaling pathway in host immune response is an important question to address. It is interesting to note that host cellular pro-inflammatory events such as HMGB1 secretion, IL-1β release and P2X7 receptor activity seem to be influenced by epigenetic modifications such as DNA methylation or by the action of histone deacetylases. It is also worth mentioning that all of these molecules are recognized to be linked to inflammasome activation, which is also known to be controlled by purinergic signaling. The impact of recognizing whether and how such danger signals can epigenetically modify some cellular mechanisms that directly influence pathogens’ survival and the associated chronic inflammation in host cells will be critical. Figure 1 represents an overview of this concept. Such knowledge can facilitate future therapeutic strategies targeting epigenetic influence on host–pathogen interaction from the purinergic signaling point of view, under different conditions or experimental models of infection-associated inflammatory diseases.

Figure 1.

A schematic representation of the relationship between epigenetic modifications induced by colonizing pathogens or by the host immune response in a bi-directional relationship. DAMP, damage-associated molecular pattern; DNMT, DNA methyltransferase; eATP, extracellular adenosine triphosphate; HAT, histone acetylase; HDAC, histone deacetylase; HMGB1, high-mobility group protein B1; PAMP, pathogen-associated molecular pattern; PRR, pattern recognition receptor.

Acknowledgments

The authors report no conflicts of interest related to this work. The authors’ work is supported by grants to ÖY and to the . ACM was supported by post-doctoral scholarships from (FAPESP) grant nos and . We would like to thank Dr David Ojcius for helpful discussions.

Conflict of interest.None declared.

REFERENCES

- Adcock IM. HDAC inhibitors as anti-inflammatory agents. Br J Pharmacol. 2007;150:829–31. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amin HM, Saeed S, Alkan S. Histone deacetylase inhibitors induce caspase-dependent apoptosis and downregulation of daxx in acute promyelocytic leukaemia with t(15;17) Br J Haematol. 2001;115:287–97. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2001.03123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbibe L, Sansonetti PJ. Epigenetic regulation of host response to LPS: causing tolerance while avoiding Toll errancy. Cell Host Microbe. 2007;1:244–6. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benakanakere M, Abdolhosseini M, Hosur K, et al. TLR2 promoter hypermethylation creates innate immune dysbiosis. J Dent Res. 2015;94:183–91. doi: 10.1177/0022034514557545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger SL. The complex language of chromatin regulation during transcription. Nature. 2007;447:407–12. doi: 10.1038/nature05915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantley MD, Bartold PM, Marino V, et al. Histone deacetylase inhibitors and periodontal bone loss. J Periodontal Res. 2011;46:697–703. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2011.01392.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantley MD, Dharmapatni AA, Algate K, et al. Class I and II histone deacetylase expression in human chronic periodontitis gingival tissue. J Periodontal Res. 2016;51:143–51. doi: 10.1111/jre.12290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson WF, Cavassani KA, Ito T, et al. Impaired CD4+ T-cell proliferation and effector function correlates with repressive histone methylation events in a mouse model of severe sepsis. Eur J Immunol. 2010;40:998–1010. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carta S, Tassi S, Semino C, et al. Histone deacetylase inhibitors prevent exocytosis of interleukin-1beta-containing secretory lysosomes: role of microtubules. Blood. 2006;108:1618–26. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-03-014126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Shi Y, Liu S, et al. PKM2: the thread linking energy metabolism reprogramming with epigenetics in cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2014a;15:11435–45. doi: 10.3390/ijms150711435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YC, Hsiao CC, Chen CJ, et al. Aberrant Toll-like receptor 2 promoter methylation in blood cells from patients with pulmonary tuberculosis. J Infect. 2014b;69:546–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2014.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi CH, Spooner R, DeGuzman J, et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis-nucleoside-diphosphate-kinase inhibits ATP-induced reactive-oxygen-species via P2X7 receptor/NADPH-oxidase signalling and contributes to persistence. Cell Microbiol. 2013;15:961–76. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crisan TO, Netea MG, Joosten LA. Innate immune memory: implications for host responses to damage-associated molecular patterns. Eur J Immunol. 2016;46:817–28.. doi: 10.1002/eji.201545497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delcuve GP, Khan DH, Davie JR. Roles of histone deacetylases in epigenetic regulation: emerging paradigms from studies with inhibitors. Clin Epigenetics. 2012;4:5. doi: 10.1186/1868-7083-4-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon SE, Stilger KL, Elias EV, et al. A decade of epigenetic research in Toxoplasma gondii. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2010;173:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donas C, Fritz M, Manríquez V, et al. Trichostatin A promotes the generation and suppressive functions of regulatory T cells. Clin Dev Immunol. 2013;2013:679804. doi: 10.1155/2013/679804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drury JL, Chung WO. DNA methylation differentially regulates cytokine secretion in gingival epithelia in response to bacterial challenges. Pathog Dis. 2015;73:1–6. doi: 10.1093/femspd/ftu005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberhard J, Banasch T, Jepsen S, et al. Differential epithelial cell response upon stimulation with the Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans strains VT 1169, VT 1560 DAM(-) and ATCC 4318. Epigenetics. 2010;5:710–5. doi: 10.4161/epi.5.8.13106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Gazzar M, Yoza BK, Chen X, et al. Chromatin-specific remodeling by HMGB1 and linker histone H1 silences proinflammatory genes during endotoxin tolerance. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:1959–71. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01862-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evankovich J, Cho SW, Zhang R, et al. High mobility group box 1 release from hepatocytes during ischemia and reperfusion injury is mediated by decreased histone deacetylase activity. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:39888–97. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.128348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Garcia JC, Barat NC, Trembley SJ, et al. Epigenetic silencing of host cell defense genes enhances intracellular survival of the rickettsial pathogen Anaplasma phagocytophilum. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000488. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glauben R, Batra A, Fedke I, et al. Histone hyperacetylation is associated with amelioration of experimental colitis in mice. J Immunol. 2006;176:5015–22. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.8.5015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Diaz E, Jordà M, Peinado MA, et al. Epigenetics of host-pathogen interactions: the road ahead and the road behind. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1003007. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haberland M, Montgomery RL, Olson EN. The many roles of histone deacetylases in development and physiology: implications for disease and therapy. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:32–42. doi: 10.1038/nrg2485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halili MA, Andrews MR, Sweet MJ, et al. Histone deacetylase inhibitors in inflammatory disease. Curr Top Med Chem. 2009;9:309–19. doi: 10.2174/156802609788085250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamon MA, Cossart P. Histone modifications and chromatin remodeling during bacterial infections. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;4:100–9. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanover JA, Krause MW, Love DC. Bittersweet memories: linking metabolism to epigenetics through O-GlcNAcylation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:312–21. doi: 10.1038/nrm3334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawtree S, Muthana M, Wilkinson JM, et al. Histone deacetylase 1 regulates tissue destruction in rheumatoid arthritis. Hum Mol Genet. 2015;24:5367–77. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddv258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennessy C, McKernan DP. Epigenetics and innate immunity: the 'unTolld' story. Immunol Cell Biol. 2016;94:631–9. doi: 10.1038/icb.2016.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horiuchi M, Morinobu A, Chin T, et al. Expression and function of histone deacetylases in rheumatoid arthritis synovial fibroblasts. J Rheumatol. 2009;36:1580–9. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.081115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber LC, Brock M, Hemmatazad H, et al. Histone deacetylase/acetylase activity in total synovial tissue derived from rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:1087–93. doi: 10.1002/art.22512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idan C, Rider P, Voronov E, et al. IL-1alpha is a DNA damage sensor linking genotoxic stress signaling to sterile inflammation and innate immunity. Sci Rep. 2015;5:14756. doi: 10.1038/srep14756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai K, Ochiai K, Okamoto T. Reactivation of latent HIV-1 infection by the periodontopathic bacterium Porphyromonas gingivalis involves histone modification. J Immunol. 2009;182:3688–95. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai K, Yamada K, Tamura M, et al. Reactivation of latent HIV-1 by a wide variety of butyric acid-producing bacteria. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2012;69:2583–92. doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-0936-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ipata PL, Balestri F. The functional logic of cytosolic 5'-nucleotidases. Curr Med Chem. 2013;20:4205–16. doi: 10.2174/0929867311320340002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer A, Fenning A, Lim J, et al. Antifibrotic activity of an inhibitor of histone deacetylases in DOCA-salt hypertensive rats. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;159:1408–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00637.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson CA, White DA, Lavender JS, et al. Human class I histone deacetylase complexes show enhanced catalytic activity in the presence of ATP and co-immunoprecipitate with the ATP-dependent chaperone protein Hsp70. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:9590–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107942200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson L, Atanasova KR, Bui PQ, et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis attenuates ATP-mediated inflammasome activation and HMGB1 release through expression of a nucleoside-diphosphate kinase. Microbes Infect. 2015;17:369–77. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2015.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karouzakis E, Gay RE, Gay S, et al. Epigenetic control in rheumatoid arthritis synovial fibroblasts. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2009;5:266–72. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2009.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawabata T, Nishida K, Takasugi K, et al. Increased activity and expression of histone deacetylase 1 in relation to tumor necrosis factor-alpha in synovial tissue of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12:R133. doi: 10.1186/ar3071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim B, Lee Y, Kim E, et al. The interleukin-1alpha precursor is biologically active and is likely a key alarmin in the IL-1 family of cytokines. Front Immunol. 2013;4:391. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krauze AV, Myrehaug SD, Chang MG, et al. A phase 2 study of concurrent radiation therapy, temozolomide, and the histone deacetylase inhibitor valproic acid for patients with glioblastoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2015;92:986–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2015.04.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leoni F, Fossati G, Lewis EC, et al. The histone deacetylase inhibitor ITF2357 reduces production of pro-inflammatory cytokines in vitro and systemic inflammation in vivo. Mol Med. 2005;11:1–15. doi: 10.2119/2006-00005.Dinarello. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leoni F, Zaliani A, Bertolini G, et al. The antitumor histone deacetylase inhibitor suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid exhibits antiinflammatory properties via suppression of cytokines. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:2995–3000. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052702999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B, Carey M, Workman JL. The role of chromatin during transcription. Cell. 2007;128:707–19. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Mei Q, Nie J, et al. Decitabine: a promising epi-immunotherapeutic agent in solid tumors. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2015;11:363–75. doi: 10.1586/1744666X.2015.1002397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindroth AM, Park YJ. Epigenetic biomarkers: a step forward for understanding periodontitis. J Periodontal Implant Sci. 2013;43:111–20. doi: 10.5051/jpis.2013.43.3.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maciejewska-Rodrigues H, Karouzakis E, Strietholt S, et al. Epigenetics and rheumatoid arthritis: the role of SENP1 in the regulation of MMP-1 expression. J Autoimmun. 2010;35:15–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2009.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinsey TA. Targeting inflammation in heart failure with histone deacetylase inhibitors. Mol Med. 2011;17:434–41. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2011.00022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins MD, Jiao Y, Larsson L, et al. Epigenetic modifications of histones in periodontal disease. J Dent Res. 2016;95:215–22. doi: 10.1177/0022034515611876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra PK, Baum M, Carbon J. DNA methylation regulates phenotype-dependent transcriptional activity in Candida albicans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:11965–70. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109631108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modak R, Das Mitra S, Vasudevan M, et al. Epigenetic response in mice mastitis: Role of histone H3 acetylation and microRNA(s) in the regulation of host inflammatory gene expression during Staphylococcus aureus infection. Clin Epigenetics. 2014;6:12. doi: 10.1186/1868-7083-6-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morandini AC, Ramos-Junior ES, Potempa J, et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis fimbriae dampen P2X7-dependent interleukin-1beta secretion. J Innate Immun. 2014b;6:831–45. doi: 10.1159/000363338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morandini AC, Savio LE, Coutinho-Silva R. The role of P2X7 receptor in infectious inflammatory diseases and the influence of ectonucleotidases. Biomed J. 2014a;37:169–77. doi: 10.4103/2319-4170.127803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang M, Zhuang S. Histone deacetylase: a potential therapeutic target for fibrotic disorders. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010;335:266–72. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.168385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul B, Barnes S, Demark-Wahnefried W, et al. Influences of diet and the gut microbiome on epigenetic modulation in cancer and other diseases. Clin Epigenetics. 2015;7:112. doi: 10.1186/s13148-015-0144-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennini ME, Pai RK, Schultz DC, et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis 19-kDa lipoprotein inhibits IFN-gamma-induced chromatin remodeling of MHC2TA by TLR2 and MAPK signaling. J Immunol. 2006;176:4323–30. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.7.4323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piccini A, Carta S, Tassi S, et al. ATP is released by monocytes stimulated with pathogen-sensing receptor ligands and induces IL-1beta and IL-18 secretion in an autocrine way. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:8067–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709684105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos-Junior ES, Morandini AC, Almeida-da-Silva CL, et al. A dual role for P2X7 receptor during Porphyromonas gingivalis infection. J Dent Res. 2015;94:1233–42. doi: 10.1177/0022034515593465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rider P, Carmi Y, Guttman O, et al. IL-1alpha and IL-1beta recruit different myeloid cells and promote different stages of sterile inflammation. J Immunol. 2011;187:4835–43. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schliehe C, Flynn EK, Vilagos B, et al. The methyltransferase Setdb2 mediates virus-induced susceptibility to bacterial superinfection. Nat Immunol. 2015;16:67–74. doi: 10.1038/ni.3046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin YH, Kim M, Kim N, et al. Epigenetic alteration of the purinergic type 7 receptor in salivary epithelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;466:704–10. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.09.095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solle M, Labasi J, Perregaux DG, et al. Altered cytokine production in mice lacking P2X(7) receptors. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:125–32. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006781200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spooner R, Yilmaz O. Nucleoside-diphosphate-kinase: a pleiotropic effector in microbial colonization under interdisciplinary characterization. Microbes Infect. 2012;14:228–37. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stammler D, Eigenbrod T, Menz S, et al. Inhibition of histone deacetylases permits lipopolysaccharide-mediated secretion of bioactive IL-1beta via a caspase-1-independent mechanism. J Immunol. 2015;195:5421–31. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1501195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan J, Cang S, Ma Y, et al. Novel histone deacetylase inhibitors in clinical trials as anti-cancer agents. J Hematol Oncol. 2010;3:5. doi: 10.1186/1756-8722-3-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veras FP, Peres RS, Saraiva ALL, et al. Fructose 1,6-bisphosphate, a high-energy intermediate of glycolysis, attenuates experimental arthritis by activating anti-inflammatory adenosinergic pathway. Sci Rep. 2015;5:15171. doi: 10.1038/srep15171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen H, Dou Y, Hogaboam CM, et al. Epigenetic regulation of dendritic cell-derived interleukin-12 facilitates immunosuppression after a severe innate immune response. Blood. 2008;111:1797–804. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-106443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong M, Polly P, Liu T. The histone methyltransferase DOT1L: regulatory functions and a cancer therapy target. Am J Cancer Res. 2015;5:2823–37. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasmin R, Siraj S, Hassan A, et al. Epigenetic regulation of inflammatory cytokines and associated genes in human malignancies. Mediators Inflamm. 2015;2015:201703. doi: 10.1155/2015/201703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yilmaz O, Sater AA, Yao L, et al. ATP-dependent activation of an inflammasome in primary gingival epithelial cells infected by Porphyromonas gingivalis. Cell Microbiol. 2010;12:188–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2009.01390.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yilmaz O, Yao L, Maeda K, et al. ATP scavenging by the intracellular pathogen Porphyromonas gingivalis inhibits P2X7-mediated host-cell apoptosis. Cell Microbiol. 2008;10:863–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.01089.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin L, Chung WO. Epigenetic regulation of human beta-defensin 2 and CC chemokine ligand 20 expression in gingival epithelial cells in response to oral bacteria. Mucosal Immunol. 2011;4:409–19. doi: 10.1038/mi.2010.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou JY, Crews FT. Release of neuronal HMGB1 by ethanol through decreased HDAC activity activates brain neuroimmune signaling. PLoS One. 2014;9:e87915. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]