Abstract

Sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) is a sphingosine containing lipid intermediate obtained from ceramide. S1P is known to be an important signaling molecule and plays multiple roles in the context of immunity. This lysophospholipid binds and activates G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) known as S1P receptors 1–5 (S1P1–5). Once activated, these GPCRs mediate signaling that can lead to alterations in cell proliferation, survival or migration, and can also have other effects such as promoting angiogenesis. In this review, we will present evidence demonstrating a role for S1P in lymphocyte migration, inflammation and infection, as well as in cancer. The therapeutic potential of targeting S1P receptors, kinases and lyase will also be discussed.

Keywords: sphingosine, S1P, FTY720, lymphocyte trafficking

Sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) is an important signaling molecule and plays a role in lymphocyte trafficking, inflammation and infection.

INTRODUCTION

Sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) regulates the proliferation, survival and migration of mammalian cells through both extracellular receptor-mediated and intracellular mechanisms (Pyne and Pyne 2010). S1P is generated by the conversion of ceramide to sphingosine by the enzyme ceramidase. The subsequent conversion of sphingosine to S1P is catalyzed by sphingosine kinase (SK). There are two isoforms of SK (SK1 and SK2). S1P binds to a family of five G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), called S1P1–5, which are coupled to heterotrimeric G-proteins and Rac or Rho to control various downstream signaling effectors, such as mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) (Pyne and Pyne 2010). In addition, it has been reported that S1P can bind to intracellular targets, such as histone deacetylases 1/2 (HDAC 1/2) (Hait et al.2009), and induce cellular responses. A recent study has shown intracellular pools of S1P localize in the Golgi, as well as in late endosomal compartments (Swaney et al.2008). S1P phosphatase dephosphorylates S1P, and the resultant sphingosine is acylated to ceramide. Also, S1P is cleaved irreversibly to hexadecenal and phosphoethanolamine (PE), by S1P lyase, which is the degradation pathway (Fig. 1). The conversion of S1P to hexadecenal and PE is considered an exit point in the sphingolipid metabolic pathway; however, both can be metabolized to produce phospholipids that can signal within cells. S1P has been implicated in regulating many diverse cellular processes and, in this review we will focus on role of S1P signaling in the context of immune responses, specifically focusing on lymphocyte migration, inflammation, infection and anti-cancer immunity.

Figure 1.

Schematic of S1P signaling. S1P is a blood-borne lipid mediator. It is less abundant in tissue fluids. This results in an S1P gradient, which is important in immune cell trafficking. Most of the biological effects of S1P are mediated by signaling through the cell surface receptors (S1P1–5), which are coupled to heterotrimeric G proteins and Rac or Rho to control various downstream signaling effectors. In the vascular system, S1P regulates angiogenesis, vascular stability and permeability. In the immune system, it is a major regulator of trafficking of T and B cells. S1P interaction with its receptor is needed for the egress of immune cells from the lymphoid organs (such as thymus and lymph nodes) into the lymphatic vessels. S1P is generated by the conversion of ceramide to sphingosine by the enzyme ceramidase. The subsequent conversion of sphingosine to S1P is catalyzed by SKs 1 and 2. S1P is cleaved irreversibly to hexadecenal and PE, by S1P lyase, which is the degradation pathway.

S1P in lymphocyte trafficking

S1P gradients play an important role in lymphocyte migration and trafficking (Baeyens et al.2015). S1P levels are usually higher in the blood and lymph than in tissues. This is important for maintaining vascular integrity, as well as for immune cell trafficking. The binding of S1P to its receptors prevents the egress of lymphocytes from lymphoid organs (Graeler and Goetzl 2002; Mandala et al.2002; Rosen, Sanna and Alfonso 2003). This S1P gradient guides the trafficking pattern of lymphocytes and helps maintain an appropriate frequency of circulating lymphocytes. The disturbance of this gradient by the addition of S1P or synthetic S1P analogs such as FTY720 (Fingolimod) can inhibit the egress of lymphocytes. Following treatment with FTY720, there is a rapid reduction in circulating lymphocytes and accumulation in the lymph nodes (Suzuki et al.1996; Yanagawa et al.1998; Yagi et al.2000; Rosen, Sanna and Alfonso 2003). In this way FTY720, which is an S1P analog and an S1PR agonist, can have potent immunosuppressive effects. This drug is known to increase graft survival without general immune suppression because only the trafficking of lymphocytes is altered, while their number and function remain unchanged (Suzuki et al.1996; Chiba et al.1998; Yanagawa et al.1998; Brinkmann et al.2001). FTY720, which binds and activates four out of the five S1P receptors, has been an invaluable tool in understanding the biological significance of S1P signaling. In fact, when first used, the immunosuppressive effect of FTY720 was attributed to its ability to induce apoptosis. However, later it was shown that circulating lymphocytes were reduced following treatment with FTY720 due to their accumulation in the lymph nodes and Peyer's patches (Gohda et al.2008). S1PR agonists cause lymphopenia in the blood and lymph by preventing the egress of lymphocytes from the lymph nodes, but not the spleen.

S1P signaling effects on various cell types

Dendritic cells (DCs) are important as antigen-presenting cells, and can play a critical role in determining the nature of the T cell response that is generated. S1P signaling has substantial effects on DCs, which express S1P receptors at various levels (Eigenbrod et al.2006). Interestingly, S1P signaling has differential effects on immature and mature DCs (Idzko et al.2002). In mature DCs, S1P inhibits the ability of the DC to induce Th1 responses, which tips the balance and in turn promotes Th2 responses. In maturing DCs, S1P can inhibit the secretion of TNF-α and IL-12 and promote the production of IL-10, thereby mediating immunosuppressive effects. In immature DCs, S1P-mediated activation of GPCRs induces transient intracellular calcium ion flux. This facilitates downstream signaling that can cause actin remodeling and chemotaxis. These distinct functions in immature DCs may allow migration of DCs to peripheral sites, where they may later receive signals to initiate maturation. S1P signaling also plays an important role in DC differentiation from monocytes. Martino et al. (2007) reported that S1P-treated precursors give rise to CD1a− DCs, which produce large amounts of TNF-α but are unable to produce IL-12 and respond to inflammatory stimuli. A recent report by Schaper, Kietzmann and Baumer (2014) further demonstrates that S1P leads to a reduction in IL-12 and IL-23 production by lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated DCs, and this was mainly mediated through the S1P1. Thus, S1P signaling can functionally alter DCs and affect the polarization of Th cells as well as inflammatory responses (Idzko et al.2006).

S1P can regulate the trafficking of peritoneal B cells (Mandala et al.2002). S1P signaling in B cells leads to accumulation of B cells in lymph nodes. Treatment with FTY720 prevents the entry of peritoneal B cells into the blood. This effect also involved the nuclear factor κB-inducing kinase expressed in stromal cells (Kunisawa et al.2008). This agonist reduces the production of intestinal secretory IgA. The regulation is independent of J chain expression and the mechanism of action involves inhibition of the egress of IgA plasmablasts from the Peyer's patches (Gohda et al.2008; Kunisawa et al.2008). FTY720 leads to the accumulation of IgA-producing B cells in the Peyer's patches and results in a decrease of these cells in the intestinal lamina propria. Similar to its effects on DCs, S1P also induces transient calcium ion flux in mature B cells. However, this effect was not observed in an immature B cell line (Nam et al.2010). Finally, signaling through S1P2 leads to maintenance of germinal centers. It also helps to keep activated B cells at the center of the follicle, which is an S1P-low zone (Matloubian et al.2004; Green et al.2011). Thus, signaling through S1P2 promotes germinal center B cell survival, maintenance and positioning of B cells within the follicle and is also important for the localization of marginal zone B cells (Cinamon et al.2004; Green et al.2011).

Some of the early studies on the effect of S1P on T cells have reported that the migration of Jurkat cells, a human T cell leukemia cell line, through a Matrigel layer was stimulated by the presence of S1P (Zheng, Kong and Goetzl 2001). There were differences in migration depending on S1P receptor expression. In another study, S1P evoked chemotaxis of mouse CD4+ and CD8+ T cells through a Matrigel layer into subcutaneous air pouches (Graeler and Goetzl 2002). However, the activation of CD4+ T cells resulted in reduced expression of S1P1,4 and the chemotactic responses were subsequently lost. This led the authors to conclude that S1P signaling may preferentially recruit naïve or central memory T cells over activated effector T cells. In T-cell development, S1P can prevent the egress of T cells from the thymus and results in reduced numbers of circulating T cells, an effect mainly mediated through S1P1 (Matloubian et al.2004). Besides cellular migration, S1P also affects the proliferation and survival of T cells. S1P protects T cells from apoptosis by suppressing the expression of the pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 family protein Bax and by preventing the cleavage-mediated activation of caspases (Goetzl, Kong and Mei 1999). S1P has also been reported to inhibit the proliferation of T cells following stimulation with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) and ionomycin, anti-CD3/CD28 or antigen-loaded DCs (Jin et al.2003). Notably, S1P has special effects on certain subsets of T cells (Jin et al.2003). For example, it increases the number and function of Foxp3+ regulatory T (Treg) cells (Daniel et al.2007). S1P signaling increases the expression of CD25 as well as Foxp3, promoting the induction of Tregs and favoring a more tolerogenic environment. In general, S1P signaling helps polarize helper T cells towards a Th2 axis and dampens the Th1 response. It does this through its effects on DCs as well as on T cells. FTY720 helps in reducing Th17 responses by inhibiting the generation of Th17 cells as well as preventing their migration out of lymph nodes (Huang et al.2007; Liao, Huang and Goetzl 2007; Mehling et al.2010). Since Th17 cells bear phenotypic features of central memory T cells, their entry into the blood is prevented by FTY720. The inhibitory effect of this agonist on Th17 responses is especially important in multiple sclerosis because it aids in achieving immunosuppression in a model where autoimmunity is largely driven by the Th17 axis (Mehling et al.2010). The role of FTY720 was found to be different in natural killer T (NKT) cells. One study has reported that NKT cell migration was unaffected by FTY720, but the secretion of IFN-γ and IL-4 was reduced (Hwang et al.2010). However, another study reported that S1P increased migration and TNF-α production by NKT cell hybridomas (Ito et al.2014). Natural killer (NK) cell trafficking is also altered by S1P signaling. In fact, one study reported that the number of NK cells in the blood was decreased after FTY720 treatment of patients with multiple sclerosis (Johnson et al.2011). Interestingly, Rolin et al. (2010) reported that S1P was able to protect tumor cells from NK-mediated lysis, and that this effect could be reversed by treatment with FTY720, or SEW2871 which inhibits S1P1. Since these drugs were able to restore tumor cell killing by NK cells, there is potential for targeting S1P signaling pathways in the treatment of cancer.

Blocking S1P signaling in hematological malignancies

Several groups have shown that SK1 is upregulated in tumor cells leading to increased production of S1P (Zhang et al.2014). This in turn leads to the activation of S1P1, which results in the activation of STAT3 (Nagahashi et al.2014). As mentioned above, S1P is also involved in the activation of NF-κB, which regulates the transcription of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α and IL-6. TNF-α stimulates SK1 to further maintain NF-κB activation, and IL-6 induces STAT3 activation (Kunkel et al.2013). Thus, many groups have utilized different strategies to target S1P signaling in hematological malignancies.

FTY720 displays differential cytotoxicity toward multiple myeloma (MM) lines in a dose and time-dependent manner, while displaying decreased cytotoxicity to mononuclear cells of the blood and the bone marrow (Yasui et al.2005). The cytotoxic effects of FTY720 were mediated through a caspase-dependent pathway, as indicated by caspase and Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) cleavage, and by the disruption of mitochondrial membrane potential. The addition of dexamethasone to FTY720 led to enhanced cell death of MM1.S cells. Furthermore, FTY720 augmented extrinsic apoptotic pathway through potentiating the effects of an anti-Fas antibody (which triggers the extrinsic pathway) (Yasui et al.2005).

In contrast, another group found that FTY720 induced cell death in a caspase-independent manner and was instead dependent on induction of autophagy in acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells, suggesting context-dependence of FTY720's effects (Wallington-Beddoe et al.2011). Moreover, in this setting, the effects were not mediated via S1P receptor blockade, but partially relied on induction of oxidative stress. The use of the phosphorylated form of FTY720 induced autophagy without subsequent cell death, suggesting that S1P receptor was not directly responsible for cytotoxicity and other pathways are implicated in FTY720's ability to induce cell death. For example, treatment with FTY720 induced production of reactive oxygen species (Wallington-Beddoe et al.2011).

Liu et al. (2007) examined cytotoxic effects of FTY720 in both leukemia and lymphoma settings. To investigate FTY720-induced cytotoxicity of leukemic cells, the group isolated B cells from chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) patients and treated leukemia cell lines MEC-1, 697 and RS4 with FTY720 (Liu et al.2007). In addition, Burkitt's lymphoma lines Raji and Ramos were also used. Similar to studies by Wallington-Beddoe et al. (2011), Liu et al. (2007) found that cell death was independent of the S1P receptor. In contrast to Wallington-Beddoe et al. (2011), who utilized a phosphorylated form of FTY720, Liu et al. (2007) pretreated cells with S1P. Both studies found that S1P receptor engagement is insufficient to induce cell death and FTY720 must exert its effects through modulation of cell death-inducing pathways. Both studies confirmed caspase independence, as demonstrated by lack of caspase-3 and PARP cleavage, and the fact that Z-VAD-FMK caspase inhibitor did not rescue the leukemic cells from FTY720-mediated cytotoxicity (Liu et al.2007; Wallington-Beddoe et al.2011). To further underscore the context-dependence of FTY720's effects, it must be highlighted that treatment of Ramos cells induced PARP cleavage, and cytotoxicity was rescued with Z-VAD-FMK, while Raji cell studies recapitulated those of leukemic cells (Liu et al.2007). Collectively, these studies shed light on other mechanisms underlying the cytotoxic effects of FTY720.

IL-6 and S1P: working in tandem in MM and lymphoma

S1P receptor engagement leads to activation of multiple signaling cascades, many of which are implicated in survival and proliferation. This fact therefore raises the question of pathway crosstalk that would enhance tumor growth. Tumors alter signaling cascades and alternatively activate pathways, leading to the activation of intricate networks that drive survival, growth and proliferation. Several studies ventured to delineate the effects of JAK/STAT3 and S1P pathways in MM and diffused large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL).

Work has been conducted to examine the roles of IL-6 and S1P signaling in MM. Following the addition of IL-6 to serum-free medium, MM cells display enhanced survival (Jourdan et al.2000) and IL-6 blockade enhances the pro-apoptotic effects of dexamethasone, a glucocorticosteroid that inhibits cell proliferation (Voorhees et al.2009; Gandhi et al.2010). The anti-apoptotic activities of IL-6 were examined in the context FTY720 treatment to evaluate whether apoptosis can be induced by FTY720, despite the presence of protective/pro-survival factors. Yasui et al. (2005) examined whether FTY720 is potent enough to overcome IL-6-mediated anti-apoptotic effects and block the activation of pro-growth and survival pathways, such as PI3K-Akt. The addition of IL-6 did not rescue FTY720-induced MM cell death. Furthermore, FTY720 inhibited PI3K-Akt and NF-κB pathways, which are crucial for cell survival and proliferation (Yasui et al.2005). This work suggests that IL-6 and S1P are working in tandem to drive tumor growth (Fig. 2).

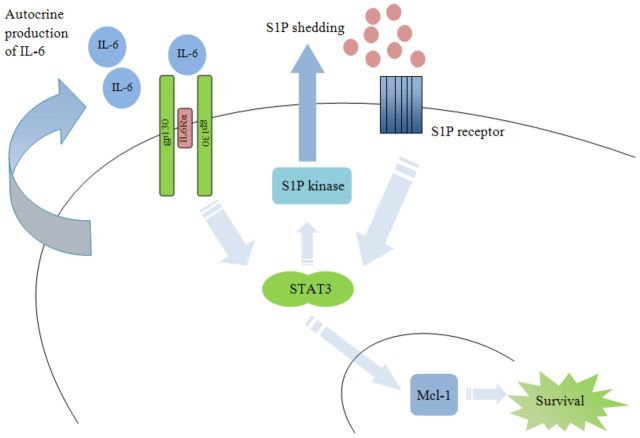

Figure 2.

Proposed model of IL-6 and S1P crosstalk in hematological malignancies. IL-6 and S1P activate STAT3, leading to expression of Mcl-1. STAT3 upregulates S1P kinase (SK) resulting in increased S1P production.

The potential of IL-6 and S1P crosstalk was examined by the group led by Li-Sheng Wang at Beijing Institute of Radiation Medicine (Li et al.2007, 2008). IL-6 receptor engagement leads to activation of the STAT3 transcription factor, a frequently overexpressed cell proliferation and survival mediator in cancer (Siveen et al.2014). Activation of STAT3 by IL-6 in MM leads to activation of Mcl-1, a member of the Bcl-2 family that inhibits apoptosis (Wuilleme-Toumi et al.2005; Li et al.2008). Li et al. (2008) examined whether activation of S1P receptors can similarly induce Mcl-1. Following S1P treatment, STAT3 was induced via engagement of S1P2 and S1P3 receptors; treatment with S1P2 antagonist JTE-013 and S1P3 antagonist CAY-10444 inhibited S1P-induced activation of MAPK and STAT3 phosphorylation, respectively (Li et al.2008). Indeed, similar to IL-6 induction of Mcl-1 via STAT3 activation, S1P-induced STAT3 activation resulted in the upregulation of Mcl-1. Induction of Mcl-1 by S1P led to protection from apoptosis following dexamethasone treatment (Li et al.2008). In addition, work by this same group has shown that IL-6 activates SK (Li et al.2007). Moreover, overexpression of SK1 protects MM cells from dexamethasone-induced apoptosis. In contrast, knockdown of SK1 abrogated the protective effects of IL-6, specifically, following knockdown of SK1, IL-6 failed to protect MM cells from dexamethasone-induced apoptosis (Li et al.2007). Taken together, these two studies suggest a model where IL-6 serves as an autocrine factor to drive production of S1P via IL-6-mediated activation of SK. The crosstalk between the two pathways would then create a feed-forward pro-survival loop, wherein shedding of S1P and autocrine production of IL-6 would drive Mcl-1 expression, leading to the inhibition of apoptosis in MM.

Activated B cell (ABC) DLBCL, a specific subset of IL-6/STAT3 highly expressing DLBCL (Lam et al.2007), has been examined in the context of S1P signaling in lymphoma. Utilization of FTY720 or knockdown of S1PR in DLBCL led to growth arrest and apoptosis (Liu et al.2012). In a xenograft model of ABC-DLBCL, knockdown of S1PR led to decreased tumor growth and metastasis to lungs, while FTY720 treatment of A20 lymphoma-bearing mice leads to a decrease in tumor burden in a STAT3-dependent fashion (Liu et al.2012). STAT3 inhibition seen in these studies highlights the efficacy of FTY720 in STAT3-dependent lymphomas.

S1P modulation in mouse xenograft studies

In vivo efficacy of FTY720 was examined in mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) mouse model depleted of natural killer cells and engrafted with Jeko, Mino and SP53 human MCL cells (Liu et al.2010). Each of the models displayed differential tumor infiltration/burdens and survivals. The time of progression to advanced stage was characterized for each cell line. For example, Jeko recipient mice displayed diffuse tumor burden, while SP53-injected mice developed retroperitoneal and abdominal tumors, as assessed by staining for human B-lymphocyte antigen (CD19) and lymphocyte common antigen (CD45) (Liu et al.2010). In Jeko recipient mice, FTY720 treatment prolonged survival by 11.5 days but was not sufficient to completely eliminate the tumors. In vitro work suggested that FTY720 was exerting its effects via downregulation of anti-apoptotic proteins (Mcl-1 and Bcl-2), induction of oxidative stress and cell cycle arrest (as evidenced by cyclin D1 downregulation) and inhibition of the growth promoting Akt pathway (Liu et al.2010). SCID mice engrafted with the Burkitt's lymphoma cell line Raji, treated with FTY720 had a 29-day survival advantage. In fact, FTY720 completely eliminated tumors in 4/12 mice, who were able to survive 200 days without signs of disease (Liu et al.2007).

In addition to FTY720 treatment and receptor knockdown, the use of SK inhibitors was examined in leukemia (Paugh et al.2008). In vitro work assessed the ability of an SK inhibitor, SK1-I, to inhibit growth and induce apoptosis. SK1-I inhibited the growth of leukemic cell lines and primary human leukemia cells, while sparing peripheral mononuclear cells (Paugh et al.2008). Strikingly, these effects were seen when S1P levels were inhibited by 50% and total cellular ceramide levels were in fact increased (Paugh et al.2008). Xenograft model confirmed the in vivo efficacy of SK1-I: tumor growth was inhibited, while organ function was preserved (Paugh et al.2008). U937 cells were injected into SCID mice, which received SK1-I once tumors engrafted. The studies were carried out for only 7 days, but mice receiving SK1-I had a 50% decrease in tumor volume, significant reduction in tumor weight and displayed tumor cell death and growth arrest (Paugh et al.2008).

Pathogens can dysregulate S1P signaling

The S1P signaling pathway has been reviewed extensively for its role in many different diseases and disorders, such as autoimmunity and vascular inflammation. Here, we will briefly discuss recent studies highlighting our present understanding of S1P signaling in various infections, such as those caused by viruses, bacteria and parasites (reviewed in Arish et al.2016).

In a recent study, single-cell suspensions were prepared from lymph nodes of HIV-1-infected patients with controlled or uncontrolled virema and uninfected controls, and responses to S1P were examined. It was found that untreated, viremic HIV-1+ patients’ CD4 naïve and central memory T cells, as well as CD8 central memory T cells had significantly diminished Akt phosphorylation responses following S1P exposure. Therefore, it was hypothesized that T cells in an uncontrolled HIV-1 infection may be compromised in their ability to migrate out of inflammatory lymph nodes (Mudd et al.2013). In addition, human cytomegalovirus, influenza virus and measles virus infections have been shown to induce SK1 activation, which influences viral gene expression and viral growth (Machesky et al.2008; Seo et al.2013; Tong et al.2013; Vijayan et al.2014). In good agreement, it was found that overexpression of S1P lyase, which degrades S1P, led to a reduction in the amplification of infectious influenza virus. Moreover, S1P lyase-overexpressing cells were much more resistant to the cytopathic effects caused by influenza virus infection, as compared to the controls (Seo et al.2010). Studies by Rosen's group have recently demonstrated that acute respiratory viral infections can be treated by blunting the cytokine storm induced by virus-specific T cells through use of a specific S1P1R agonist (Walsh et al.2014).

Another study examined the trafficking of Yersinia pestis-infected cells between lymph nodes via the lymphatic system and found that it was dependent on S1P. Importantly, it was found that the use of the S1P1-specific agonist, SEW2871, did not inhibit the number of bacteria that are able to invade to the draining lymph nodes, but were able to block node-to-node travel of intracellular Y. pestis. In good agreement, they showed that mice with a conditional knockout of S1P1 in CX3CR1-expressing cells have reduced spread of bacteria to secondary lymph nodes (St. John et al. 2014). To investigate the significance of the recirculation of T cells from the lymph nodes to the spleen during a Trypanosoma cruzi infection, resistant (C57BL/6) and susceptible (A/Sn) mice were treated with FTY720 after challenge. It was found that blocking S1P resulted in a significant increase in the susceptibility to infection, as evidenced by elevated parasitemia and accelerated mortality, which demonstrates that the recirculation of T lymphocytes mediated by S1P plays an important role during acquired or vaccine-induced protective immune responses to T. cruzi infection (Dominguez et al.2012). It has been reported that S1P-mediated mycobactericidal activity is due to the activation of phospholipase D and phagolysosome maturation in differentiated THP-1 cells. In addition, this same group has shown that treatment with S1P can result in bacterial clearance in a mouse model of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection (Garg et al.2004). Furthermore, patients infected with M. tuberculosis exhibited low levels of S1P compared with healthy controls, and treatment of bronchoalveolar lavage cells isolated from these patients with 5-mm S1P leads to a reduction in the intracellular growth of M. tuberculosis (Garg et al.2006).

Another group used a murine Bordetella pertussis model to examine the effects of the S1PR agonist AAL-R on pulmonary inflammation during infection. It was found that treatment with AAL-R led to a reduction in the expression of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines and attenuated lung pathology in infected mice (Skerry et al.2015). Given the critical role, S1P has been demonstrated to play in the context of cancer, infection and other diseases, many groups have focused on targeting this pathway using S1P signaling inhibitors, analogs and antibodies.

Current strategies targeting S1P signaling and metabolism

FTY720 initially received attention due to its ability to increase lymphocyte homing to lymph nodes and thus causing a decrease in circulating lymphocytes. This effect is mediated through strong affinity of phosphorylated FTY720 (via the SKs) for the S1P1 receptor and subsequent functional antagonism through receptor internalization (Brinkmann et al.2010). The well-known side effect of FTY720 is reflex bradycardia, thought to be via S1P3 stimulation (Budde et al.2002; Sanna et al.2004). S1P3 stimulation has been connected with modulation of the inward rectifier potassium current, which affects resting membrane potential in guinea pig, mouse and human atrial cardiomyocytes. However, the exact mechanism for FTY720-induced bradycardia is still not completely known (Himmel et al.2000). Structural analog KRP-203 shares the same head group as FTY720, with a modified tail region that retains hydrophobicity while reducing rotational freedom that would be seen in the straight chain hydrocarbon tail of FTY720 (Fig. 3). More importantly, KRP-203 shows a similar profile in immune modulation, while having a marked reduction in the occurrence of bradycardia (Shimizu et al.2005). Because of favorable immunomodulation and low incidence of undesirable side effects, KRP-203 is being examined in a phase I trial for use in patients undergoing stem cell transplants for hematological malignancies (NCT01830010).

Figure 3.

The chemical structures of FTY720 phosphate and KRP203. FTY720 phosphate is a well-characterized S1P1,3–5 agonist and KRP203 is an S1P1-specific agonist.

The two isoforms of SK, SK1 and SK2, are responsible for different kinetics and expression patterns; therefore, it has become increasingly important to generate isoform-specific inhibitors. Most attempts to generate isoform-specific inhibitors have been aimed at SK1 but more attention is being put on SK2 (Gestaut et al.2014, Pyne, Bittman and Pyne 2011). ABC294640 is an SK2-selective inhibitor with favorable oral availability and low toxicity. Moreover, it shows low off-target effects for other serine/threonine protein kinases, which is a concern for any kinase inhibitor (French et al.2010). The compound has been shown to be efficacious in murine models of lupus, colitis, osteoarthritis and chemoresistant breast cancer (Chumanevich et al.2010; Antoon et al.2011; Fitzpatrick et al.2011; Snider et al.2013). ABC294640 is currently recruiting for a phase I trial for patients with pancreatic and other solid tumors (NCT01488513).

Many studies have supported the role of S1P in angiogenesis, specifically in the context of cancer progression, because of its ability to affect actions of endothelial cells, cell junctions and adhesion molecules in vasculature via S1P1 (Anelli et al.2008; Purschke et al.2014). Sonepcizumab (LT1009) (O'Brien et al.2009), a humanized version of the sphingosine antibody, sphingomab, (Visentin et al.2006) has completed clinical trials for both auto-immune diseases and solid tumors. It is currently being evaluated in a phase 2 clinical trial for renal cell carcinoma (NCT01762033). Sonepcizumab demonstrates high selectivity and affinity for S1P over other lipids and phospholipids as well as favorable in vivo stability. These antibodies have shown the ability to reduce tumor size and metastasis potential in human cancer models of breast, ovarian, lung and melanoma, presumably through a compensation of neutralizing the effects of sphingosine in angiogenesis as well as cell-signaling events.

CONCLUSIONS

There are many ways to target sphingosine signaling and metabolism; thus, it can be a challenge to determine which part of the pathway has the greatest potential as a therapeutic target. Targeting the SKs is a challenge not only due to the similar homology, but also due to conservation of kinase domains throughout many enzymes. This particular obstacle has been overcome with compounds such as ABC294640. This success is attributed to target the lipid-binding region of the kinase, as opposed to the ATP-binding site, which is much more conserved across kinases. Differentiating between the SKs depends on lipid-binding pocket sizes of each kinase, steric bulk of the lipid portions of inhibitors and linker regions between polar head groups and lipid tail regions. Utilization of directed in silico predictive homology models of kinases and small molecule inhibitors followed by in vitro testing of the synthesized compounds has yielded SK1-selective inhibitors (Kennedy et al.2011).

Targeting the receptors offers similar challenges. GPCRs suffer from the same homology limitations as kinases, such as in the case of FTY720 and bradycardia mentioned above. Developing more subtype-selective inhibitors would have the ability to bypass these unwanted effects. Additionally, altering lipophilicity of the tail region of existing S1P1-selective agonists can improve blood-brain barrier penetration and allow for a more robust effect in certain central nervous system (CNS) maladies such as multiple sclerosis (Bolli et al.2014). However, as with virtually every other therapy on the market, some measure of non-specificity may be inevitable, yet acceptable, when considering the potential outcomes of treatment versus non-treatment of an aggressive disease.

In summary, S1P signaling is involved in lymphocyte migration, inflammation, infection and tumorigenesis (Maceyka and Spiegel 2014). Many groups have focused on targeting S1P receptors and kinases in order to modulate this pathway. Currently, efforts have shifted to developing therapeutics focused on targeting S1P lyase (S1PL), which degrades intracellular S1P (Sanllehí et al. 2015). To gain a better understanding of trafficking of cells between blood and tissue spaces, tissue-engineering approaches using biomaterials are being developed to investigate S1P metabolic activity and signaling gradients (Ogle et al.2014). It will be interesting to determine the efficacy of these novel therapeutic agents and gain insight into the mechanisms regulating the balance between the SK/phosphatase activity during infection and inflammatory processes.

Acknowledgments

Given the wide breadth of studies examining the effects of S1P signaling only recent reviews and closely related articles have been cited, and we apologize to those whose work may have been omitted due to space considerations.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [R21 CA199544-01 and R21 CA184469 to TJW].

Conflict of interest. None declared.

REFERENCES

- Anelli V, Gault CR, Cheng AB, et al. Sphingosine kinase 1 is up-regulated during hypoxia in U87MG glioma cells. Role of hypoxia-inducible factors 1 and 2. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:3365–75. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708241200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoon JW, White MD, Slaughter EM, et al. Targeting NFkB mediated breast cancer chemoresistance through selective inhibition of sphingosine kinase-2. Cancer Biol Ther. 2011;11:678–89. doi: 10.4161/cbt.11.7.14903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arish M, Husein A, Kashif M, et al. Sphingosine-1-phosphate signaling: unraveling its role as a drug target against infectious diseases. Drug Discov Today. 2016;21:133–42. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2015.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baeyens A, Fang V, Chen C, et al. Exit strategies: S1P signaling and t cell migration. Trends Immunol. 2015;36:778–87. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2015.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolli MH, Abele S, Birker M, et al. Novel S1P(1) receptor agonists–part 3: from thiophenes to pyridines. J Med Chem. 2014;57:110–30. doi: 10.1021/jm4014696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkmann V, Billich A, Baumruker T, et al. Fingolimod (FTY720): discovery and development of an oral drug to treat multiple sclerosis. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9:883–97. doi: 10.1038/nrd3248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkmann V, Pinschewer DD, Feng L, et al. FTY720: altered lymphocyte traffic results in allograft protection. Transplantation. 2001;72:764–9. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200109150-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budde K, Schmouder RL, Brunkhorst R, et al. First human trial of FTY720, a novel immunomodulator, in stable renal transplant patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:1073–83. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V1341073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiba K, Yanagawa Y, Masubuchi Y, et al. FTY720, a novel immunosuppressant, induces sequestration of circulating mature lymphocytes by acceleration of lymphocyte homing in rats. I. FTY720 selectively decreases the number of circulating mature lymphocytes by acceleration of lymphocyte homing. J Immunol. 1998;160:5037–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chumanevich AA, Poudyal D, Cui X, et al. Suppression of colitis-driven colon cancer in mice by a novel small molecule inhibitor of sphingosine kinase. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31:1787–93. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cinamon G, Matloubian M, Lesneski MJ, et al. Sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 1 promotes B cell localization in the splenic marginal zone. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:713–20. doi: 10.1038/ni1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel C, Sartory N, Zahn N, et al. FTY720 ameliorates Th1-mediated colitis in mice by directly affecting the functional activity of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2007;178:2458–68. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.4.2458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez MR, Ersching J, Lemos R, et al. Re-circulation of lymphocytes mediated by sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor-1 contributes to resistance against experimental infection with the protozoan parasite Trypanosoma cruzi. Vaccine. 2012;30:2882–91. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eigenbrod S, Derwand R, Jakl V, et al. Sphingosine kinase and sphingosine-1-phosphate regulate migration, endocytosis and apoptosis of dendritic cells. Immunol Invest. 2006;35:149–65. doi: 10.1080/08820130600616490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick LR, Green C, Maines LW, et al. Experimental osteoarthritis in rats is attenuated by ABC294640, a selective inhibitor of sphingosine kinase-2. Pharmacology. 2011;87:135–43. doi: 10.1159/000323911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French KJ, Zhuang Y, Maines LW, et al. Pharmacology and antitumor activity of ABC294640, a selective inhibitor of sphingosine kinase-2. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010;333:129–39. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.163444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi AK, Kang J, Capone L, et al. Dexamethasone synergizes with lenalidomide to inhibit multiple myeloma tumor growth, but reduces lenalidomide-induced immunomodulation of T and NK cell function. Curr Cancer Drug Tar. 2010;10:155–67. doi: 10.2174/156800910791054239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg SK, Santucci MB, Panitti M, et al. Does sphingosine 1-phosphate play a protective role in the course of pulmonary tuberculosis? Clin Immunol. 2006;121:260–4. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg SK, Volpe E, Palmieri G, et al. Sphingosine 1–phosphate induces antimicrobial activity both in vitro and in vivo. J Infect Dis. 2004;189:2129–38. doi: 10.1086/386286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gestaut MM, Antoon JW, Burow ME, et al. Inhibition of sphingosine kinase-2 ablates androgen resistant prostate cancer proliferation and survival. Pharmacol Rep. 2014;66:174–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pharep.2013.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goetzl EJ, Kong Y, Mei B. Lysophosphatidic acid and sphingosine 1-phosphate protection of T cells from apoptosis in association with suppression of Bax. J Immunol. 1999;162:2049–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gohda M, Kunisawa J, Miura F, et al. Sphingosine 1-phosphate regulates the egress of IgA plasmablasts from Peyer's patches for intestinal IgA responses. J Immunol. 2008;180:5335–43. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.8.5335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graeler M, Goetzl EJ. Activation-regulated expression and chemotactic function of sphingosine 1-phosphate receptors in mouse splenic T cells. FASEB J. 2002;16:1874–8. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0548com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green JA, Suzuki K, Cho B, et al. The sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor S1P(2) maintains the homeostasis of germinal center B cells and promotes niche confinement. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:672–80. doi: 10.1038/ni.2047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hait NC, Allegood J, Maceyka M, et al. Regulation of histone acetylation in the nucleus by sphingosine-1-phosphate. Science. 2009;325:1254–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1176709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himmel HM, Meyer Zu Heringdorf D, Graf E, et al. Evidence for Edg-3 receptor-mediated activation of I(K.ACh) by sphingosine-1-phosphate in human atrial cardiomyocytes. Mol Pharmacol. 2000;58:449–54. doi: 10.1124/mol.58.2.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang MC, Watson SR, Liao JJ, et al. Th17 augmentation in OTII TCR plus T cell-selective type 1 sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor double transgenic mice. J Immunol. 2007;178:6806–13. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.11.6806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang SJ, Kim JH, Kim HY, et al. FTY720, a sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor modulator, inhibits CD1d-restricted NKT cells by suppressing cytokine production but not migration. Lab Invest. 2010;90:9–19. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2009.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idzko M, Hammad H, van Nimwegen M, et al. Local application of FTY720 to the lung abrogates experimental asthma by altering dendritic cell function. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:2935–44. doi: 10.1172/JCI28295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idzko M, Panther E, Corinti S, et al. Sphingosine 1-phosphate induces chemotaxis of immature and modulates cytokine-release in mature human dendritic cells for emergence of Th2 immune responses. FASEB J. 2002;16:625–7. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0625fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito S, Iwaki S, Kondo R, et al. TNF-alpha production in NKT cell hybridoma is regulated by sphingosine-1-phosphate: implications for inflammation in atherosclerosis. Coronary Artery Dis. 2014;25:311–20. doi: 10.1097/MCA.0000000000000082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Y, Knudsen E, Wang L, et al. Sphingosine 1-phosphate is a novel inhibitor of T-cell proliferation. Blood. 2003;101:4909–15. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-09-2962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson TA, Evans BL, Durafourt BA, et al. Reduction of the peripheral blood CD56(bright) NK lymphocyte subset in FTY720-treated multiple sclerosis patients. J Immunol. 2011;187:570–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jourdan M, Vos JD, Mechti N, et al. Regulation of Bcl-2-family proteins in myeloma cells by three myeloma survival factors: interleukin-6, interferon-alpha and insulin-like growth factor 1. Cell Death Differ. 2000;7:1244–52. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy AJ, Mathews TP, Kharel Y, et al. Development of amidine-based sphingosine kinase 1 nanomolar inhibitors and reduction of sphingosine 1-phosphate in human leukemia cells. J Med Chem. 2011;54:3524–48. doi: 10.1021/jm2001053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunisawa J, Gohda M, Kurashima Y, et al. Sphingosine 1-phosphate-dependent trafficking of peritoneal B cells requires functional NFkappaB-inducing kinase in stromal cells. Blood. 2008;111:4646–52. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-120071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunkel GT, Maceyka M, Milstien S, et al. Targeting the sphingosine-1-phosphate axis in cancer, inflammation and beyond. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2013;12:688–702. doi: 10.1038/nrd4099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam LT, Wright G, Davis RE, et al. Cooperative signaling through the signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 and nuclear factor-κB pathways in subtypes of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2007;111:3701–13. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-09-111948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q-F, Wu C-T, Duan H-F, et al. Activation of sphingosine kinase mediates suppressive effect of interleukin-6 on human multiple myeloma cell apoptosis. Brit J Haematol. 2007;138:632–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06711.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q-F, Wu C-T, Guo Q, et al. Sphingosine 1-phosphate induces Mcl-1 upregulation and protects multiple myeloma cells against apoptosis. Biochem Bioph Res Co. 2008;371:159–62. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao JJ, Huang MC, Goetzl EJ. Cutting edge: alternative signaling of Th17 cell development by sphingosine 1-phosphate. J Immunol. 2007;178:5425–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.9.5425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Alinari L, Chen C-S, et al. FTY720 shows promising in vitro and in vivo preclinical activity by downmodulating cyclin D1 and phospho-Akt in mantle cell lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:3182–92. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Zhao X, Frissora F, et al. FTY720 demonstrates promising preclinical activity for chronic lymphocytic leukemia and lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma. Blood. 2007;111:275–84. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-10-053884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Deng J, Wang L, et al. S1PR1 is an effective target to block STAT3 signaling in activated B cell–like diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2012;120:1458–65. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-12-399030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maceyka M, Spiegel S. Sphingolipid metabolites in inflammatory disease. Nature. 2014;510:58–67. doi: 10.1038/nature13475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machesky NJ, Zhang G, Raghavan B, et al. Human cytomegalovirus regulates bioactive sphingolipids. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:26148–60. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710181200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandala S, Hajdu R, Bergstrom J, et al. Alteration of lymphocyte trafficking by sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor agonists. Science. 2002;296:346–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1070238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martino A, Volpe E, Auricchio G, et al. Sphingosine 1-phosphate interferes on the differentiation of human monocytes into competent dendritic cells. Scand J Immunol. 2007;65:84–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2006.01860.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matloubian M, Lo CG, Cinamon G, et al. Lymphocyte egress from thymus and peripheral lymphoid organs is dependent on S1P receptor 1. Nature. 2004;427:355–60. doi: 10.1038/nature02284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehling M, Lindberg R, Raulf F, et al. Th17 central memory T cells are reduced by FTY720 in patients with multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2010;75:403–10. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181ebdd64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mudd JC, Murphy P, Manion M, et al. Impaired T-cell responses to sphingosine-1-phosphate in HIV-1 infected lymph nodes. Blood. 2013;121:2914–22. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-07-445783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagahashi M, Hait NC, Maceyka M, et al. Sphingosine-1-phosphate in chronic intestinal inflammation and cancer. Adv Biol Regul. 2014;54:112–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jbior.2013.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam JH, Shin DH, Min JE, et al. Ca2+ signaling induced by Sphingosine 1-phosphate and lysophosphatidic acid in mouse b cells. Mol Cells. 2010;29:85–91. doi: 10.1007/s10059-010-0020-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien N, Jones ST, Williams DG, et al. Production and characterization of monoclonal anti-sphingosine-1-phosphate antibodies. J Lipid Res. 2009;50:2245–57. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M900048-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogle ME, Sefcik LS, Awojoodu AO, et al. Engineering in vivo gradients of sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor ligands for localized microvascular remodeling and inflammatory cell positioning. Acta Biomater. 2014;10:4704–14. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2014.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paugh SW, Paugh BS, Rahmani M, et al. A selective sphingosine kinase 1 inhibitor integrates multiple molecular therapeutic targets in human leukemia. Blood. 2008;112:1382–91. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-02-138958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purschke WG, Hoehlig K, Buchner K, et al. Identification and characterization of a mirror-image oligonucleotide that binds and neutralizes Sphingosine-1-Phosphate, a central mediator of angiogenesis. Biochem J. 2014 doi: 10.1042/BJ20131422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyne NJ, Pyne S. Sphingosine 1-phosphate and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:489–503. doi: 10.1038/nrc2875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyne S, Bittman R, Pyne NJ. Sphingosine kinase inhibitors and cancer: seeking the golden sword of Hercules. Cancer Res. 2011;71:6576–82. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-2364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolin J, Sand KL, Knudsen E, et al. FTY720 and SEW2871 reverse the inhibitory effect of S1P on natural killer cell mediated lysis of K562 tumor cells and dendritic cells but not on cytokine release. Cancer Immunol Immun. 2010;59:575–86. doi: 10.1007/s00262-009-0775-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen H, Sanna G, Alfonso C. Egress: a receptor-regulated step in lymphocyte trafficking. Immunol Rev. 2003;195:160–77. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2003.00068.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanllehí P, Abad J-L, Casas J, et al. Inhibitors of sphingosine-1-phosphate metabolism (sphingosine kinases and sphingosine-1-phosphate lyase) Chem Phys Lipids. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2015.07.007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2015.07.007 (29 June 2016, date last accessed) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanna MG, Liao J, Jo E, et al. Sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) receptor subtypes S1P1 and S1P3, respectively, regulate lymphocyte recirculation and heart rate. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:13839–48. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311743200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaper K, Kietzmann M, Baumer W. Sphingosine-1-phosphate differently regulates the cytokine production of IL-12, IL-23 and IL-27 in activated murine bone marrow derived dendritic cells. Mol Immunol. 2014;59:10–8. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2013.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo Y-J, Blake C, Alexander S, et al. Sphingosine 1-phosphate-metabolizing enzymes control influenza virus propagation and viral cytopathogenicity. J Virol. 2010;84:8124–31. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00510-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo YJ, Pritzl CJ, Vijayan M, et al. Sphingosine kinase 1 serves as a pro-viral factor by regulating viral RNA synthesis and nuclear export of viral ribonucleoprotein complex upon influenza virus infection. PLoS One. 2013;8:e75005. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu H, Takahashi M, Kaneko T, et al. KRP-203, a novel synthetic immunosuppressant, prolongs graft survival and attenuates chronic rejection in rat skin and heart allografts. Circulation. 2005;111:222–9. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000152101.41037.AB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siveen KS, Sikka S, Surana R, et al. Targeting the STAT3 signaling pathway in cancer: role of synthetic and natural inhibitors. BBA-Rev Cancer. 2014;1845:136–54. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2013.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skerry C, Scanlon K, Rosen H, et al. Sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor agonism reduces bordetella pertussis–mediated lung pathology. J Infect Dis. 2015;211:1883–6. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snider AJ, Ruiz P, Obeid LM, et al. Inhibition of sphingosine kinase-2 in a murine model of lupus nephritis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e53521. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St. John AL, Ang WXG, Huang M-N, et al. S1P-dependent trafficking of intracellular Yersinia pestis through lymph nodes establishes buboes and systemic infection. Immunity. 2014;41:440–50. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki S, Enosawa S, Kakefuda T, et al. A novel immunosuppressant, FTY720, with a unique mechanism of action, induces long-term graft acceptance in rat and dog allotransplantation. Transplantation. 1996;61:200–5. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199601270-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swaney JS, Moreno KM, Gentile AM, et al. Sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) is a novel fibrotic mediator in the eye. Exp Eye Res. 2008;87:367–75. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2008.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong S, Tian J, Wang H, et al. H9N2 avian influenza infection altered expression pattern of Sphiogosine-1-phosphate Receptor 1 in BALB/c mice. Virol J. 2013;10:1–8. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-10-296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijayan M, Seo Y-J, Pritzl CJ, et al. Sphingosine kinase 1 regulates measles virus replication. Virology. 2014;450–451:55–63. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2013.11.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visentin B, Vekich JA, Sibbald BJ, et al. Validation of an anti-sphingosine-1-phosphate antibody as a potential therapeutic in reducing growth, invasion, and angiogenesis in multiple tumor lineages. Cancer Cell. 2006;9:225–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voorhees P, Chen Q, Small GW, et al. Targeted Inhibition of interleukin-6 with CNTO 328 sensitizes pre-clinical models of multiple myeloma to dexamethasone-mediated cell death. Brit J Haematol. 2009;145:481–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07647.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallington-Beddoe CT, Hewson J, Bradstock KF, et al. FTY720 produces caspase-independent cell death of acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells. Autophagy. 2011;7:707–15. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.7.15154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh KB, Teijaro JR, Brock LG, et al. Animal model of respiratory syncytial virus: cd8+ T cells cause a cytokine storm that is chemically tractable by sphingosine-1-phosphate 1 receptor agonist therapy. J Virol. 2014;88:6281–93. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00464-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wuilleme-Toumi S, Robillard N, Gomez P, et al. Mcl-1 is overexpressed in multiple myeloma and associated with relapse and shorter survival. Leukemia. 2005;19:1248–52. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yagi H, Kamba R, Chiba K, et al. Immunosuppressant FTY720 inhibits thymocyte emigration. Eur J Immunol. 2000;30:1435–44. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(200005)30:5<1435::AID-IMMU1435>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanagawa Y, Sugahara K, Kataoka H, et al. FTY720, a novel immunosuppressant, induces sequestration of circulating mature lymphocytes by acceleration of lymphocyte homing in rats. II. FTY720 prolongs skin allograft survival by decreasing T cell infiltration into grafts but not cytokine production in vivo. J Immunol. 1998;160:5493–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasui H, Hideshima T, Raje N, et al. FTY720 induces apoptosis in multiple myeloma cells and overcomes drug resistance. Cancer Res. 2005;65:7478–84. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Wang Y, Wan Z, et al. Sphingosine kinase 1 and cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e90362. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Y, Kong Y, Goetzl EJ. Lysophosphatidic acid receptor-selective effects on Jurkat T cell migration through a Matrigel model basement membrane. J Immunol. 2001;166:2317–22. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.4.2317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]