Abstract

Macrophage foam cell formation is a key event in atherosclerosis. Several triggers induce low-density lipoprotein (LDL) uptake by macrophages to create foam cells, including infections with Porphyromonas gingivalis and Chlamydia pneumoniae, two pathogens that have been linked to atherosclerosis. While gene regulation during foam cell formation has been examined, comparative investigations to identify shared and specific pathogen-elicited molecular events relevant to foam cell formation are not well documented. We infected mouse bone marrow-derived macrophages with P. gingivalis or C. pneumoniae in the presence of LDL to induce foam cell formation, and examined gene expression using an atherosclerosis pathway targeted plate array. We found over 30 genes were significantly induced in response to both pathogens, including PPAR family members that are broadly important in atherosclerosis and matrix remodeling genes that may play a role in plaque development and stability. Six genes mainly involved in lipid transport were significantly downregulated. The response overall was remarkably similar and few genes were regulated in a pathogen-specific manner. Despite very divergent lifestyles, P. gingivalis and C. pneumoniae activate similar gene expression profiles during foam cell formation that may ultimately serve as targets for modulating infection-elicited foam cell burden, and progression of atherosclerosis.

Keywords: innate immunity, Porphyromonas gingivalis, Chlamydia pneumoniae, macrophage, foam cell, atherosclerosis

Porphyromonas gingivalis and Chlamydia pneumonia induce a shared gene expression pattern during foam cell formation.

INTRODUCTION

Atherosclerosis is now recognized as a chronic inflammatory disorder. One of the earliest events in the development of atherosclerotic plaques is the appearance of fatty streaks along the vessel wall, formed by the transition of lipid laden macrophages to foam cells. Later in the course of disease, foam cells continue to play a central role in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis, including plaque progression and the development of unstable plaques. Because of this, understanding the mechanisms by which macrophages contribute to the development of atherosclerosis has become a major research goal.

In addition to common risk factors associated with atherosclerosis, such as hyperlipidemia, smoking, obesity and diabetes, a number of chronic infections have been suggested to contribute to disease progression, including the oral pathogen, Porphyromonas gingivalis, and the respiratory pathogen, Chlamydia pneumoniae. Both C. pneumoniae (Kuo et al.1993; Taylor-Robinson and Thomas 2000) and P. gingivalis (Chiu 1999; Haraszthy et al.2000; Ishihara et al.2004) have been detected within atherosclerotic lesions, and both have been demonstrated in vivo to promote atherosclerosis in mouse models of disease (Li et al.2002; Campbell and Kuo 2004; Gibson et al.2004, 2006; Naiki et al.2008; Chen et al.2010; Maekawa et al.2011; Di Pietro et al.2013; Joshi et al.2013). Moreover, infection with either P. gingivalis (Qi, Miyakawa and Kuramitsu 2003; Giacona et al.2004) or C. pneumoniae (Kalayoglu and Byrne 1998; Kalayoglu et al.2000) has also been demonstrated to induce the formation of foam cells from resting macrophages exposed to low-density lipoprotein (LDL) in vitro. However, these pathogens could not be more different in terms of their growth, development and biological niche.

Porphyromonas gingivalis is an anaerobic Gram-negative rod found in the oral cavity where it has been strongly associated with periodontal disease, one of the most common chronic diseases in humans (reviewed in Mysak et al.2014). Chlamydia pneumoniae, on the other hand, is an obligate intracellular Gram-negative organism associated with a mild ‘atypical’ pneumonia (Hammerschlag 2000; Kumar and Hammerschlag 2007). Both pathogens activate and evade a variety of innate immune signaling pathways, as well as cell death pathways, demonstrating a complex interaction with the host (reviewed in Gibson, Ukai and Genco 2008; Shimada, Crother and Arditi 2012). We recently reported on the gene expression profile in vivo, using mouse models for both P. gingivalis and C. pneumoniae induced atherosclerosis in the apolipoprotein E (ApoE)-deficient mouse, identifying both unique and shared genetic signatures in the aortas of infected mice (Kramer et al.2014). However, because of the mixed cellular make-up of the aorta and its associated plaque, it was not possible to assign gene expression signatures to specific cell types.

Given the important role of the macrophage in driving atherosclerosis (Moore, Sheedy and Fisher 2013), we set out to determine the molecular signature for these two atherosclerosis-associated pathogens in vitro during foam cell formation. We identified both shared and pathogen-specific signals, demonstrating that while there are multiple pathways that can lead to foam cell formation, there are clearly pivotal steps in this process that diverse stimuli can trigger. Our findings support the hypothesis that bacterial infections can modify a chronic inflammatory disease like atherosclerosis. While pathogen-specific signals may be relevant to understanding the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis, shared signals represent potentially novel therapeutic targets to modify the course of disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethics statement

All animal-use protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Boston University, in accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health. Every effort was made to minimize discomfort, pain and distress in the animals. Boston University is accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care.

Preparation of murine bone marrow-derived macrophages

C57BL/6J mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). Bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) were prepared as described previously (He et al.2010). Briefly, bone marrows were flushed from femurs and tibiae of C57BL/6 mice, 6–8 weeks age, and the cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS, 20 μg ml−1 of gentamicin and 20% (v/v) of L929 condition medium (containing M-CSF). The cells were incubated at 37°C/5% CO2 for 7–9 days to allow differentiation of macrophages; gentamicin was removed from the culture medium 1 day prior to infection.

Propagation of Porphyromonas gingivalis

Porphyromonas gingivalis strain 381 was plated on BHI agar plates, cultivated anaerobically for 3–5 days at 37°C; colonies were subsequently harvested to seed BHI-yeast extract broth cultures, as described previously (Baer, Huang and Gibson 2009). After 24 h of growth, bacteria were harvested, washed and suspended in antibiotic-free complete RPMI-1640 cell culture medium.

Propagation of Chlamydia pneumoniae

Chlamydia pneumoniae strain AO3 was kindly provided by Dr Charlotte Gaydos (Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD). Gradient purified elementary bodies were prepared after propagation in L929 fibroblasts, as described previously (He et al.2010), and the titer calculated as inclusion-forming units ml−1. To ensure accurate titers, all aliquoted stocks were frozen at −80°C, and thawed once, at the time of use. All stocks used for these studies tested negative for Mycoplasma contamination by PCR (Ossewaarde et al.1996).

Macrophage infections

BMDMs were infected with P. gingivalis at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 100, or C. pneumoniae at a MOI of 10, in the presence or absence of human LDL (200 μg ml−1, Intracell, Fredrick, MD). In the case of C. pneumoniae, infection was initiated by centrifugation at 1500 × g for 1 h at 35°C. Infected cells were incubated at 37°C/5% CO2 for 24 h, and cell culture supernatant fluids were harvested for ELISA or lipid peroxidation assay. Attached cells were processed for either foam cell identification or lysed with RLT lysis buffer (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and stored frozen for RNA extraction.

Lipid staining and foam cell counts

Foam cell formation assays were performed as previously described (Shaik-Dasthagirisaheb et al.2013). Briefly, BMDMs were plated on glass coverslips in 24-well tissue culture dishes. Following infection, BMDMs were washed with DPBS, paraformaldehyde fixed, washed and stained with oil red O solution (100 mg ml−1 in 70% isopropanol, 30% water) for 15 min. Following washing with DPBS, the coverslips were mounted on glass slides and visualized under a microscope. Five digital images were taken of representative microscopic fields for each condition in each experiment, and the percentage of oil red O stained cells was calculated using Image J software (Schneider, Rasband and Eliceiri 2012). Data reported were gathered from 450 cells per visual field in five separate fields, and performed in a blinded manner.

Lipid peroxidation assay

The level of oxidized LDL present in culture supernatant fluids from BMDMs post P. gingivalis or C. pneumoniae treatments was determined using a thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) assay (OxiSelect TBARS Assay kit, Cell Biolabs, San Diego, CA) according to manufacturer's instructions.

Cytokine assay

Cell culture supernatant fluids were assayed using commercially available ELISA kits for murine TNF-α (eBioscience, San Diego, CA), IL-1β and IL-6 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Plates were read in an ELx800 Universal Microplate Reader (Bio-Tek Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT), and data analyzed using SoftMax Pro 4.6 software.

PCR array

RNA was purified from infected cells lysed with RLT buffer using the RNeasy Kit (Qiagen). RNA was quantified by using a Nanodrop 1000 (Fisher Scientific), and quality of the RNA was evaluated by A260/A280. About 1 μg of total RNA was reverse transcribed using RT2 First Strand Kit (Qiagen). Briefly, 10 μl of total RNA was mixed with 10 μl of RT cocktail reaction mix and the cDNA synthesis was performed by incubation at 42°C for 15 min. cDNA was analyzed using the RT2 Profiler PCR Array Mouse Atherosclerosis Array (Qiagen) on a real-time PCR machine (ABI 7900 HT, Applied Biosystems, ThermoFisher Scientific, Grand Island, NY). Gene expression was determined using ΔΔCt method, and normalized to β-actin. Genes were considered differentially expressed if they demonstrated a 2-fold or greater change in expression compared to the uninfected control group, with a significant P value ≤ 0.05.

Real-time PCR

To validate the microarray results, real-time qPCR assays were performed using Taqman assays (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) on a subset of genes that include peroxisome proliferator activated receptor delta (Ppar-δ; assay ID# Mm00439546_s1), peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (Ppar-γ; assay ID# Mm01157262_m1) and tumor necrosis factor (Tnf; assay ID# Mm00802247_m1) genes. Complementary DNA (cDNA) was prepared from RNA using the RNA-to-cDNA Kit (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY), and the PCR reactions were carried out on a StepOne Real-Time PCR System (Life Technologies). Fold expression was calculated using actin beta (Actb; assay ID# Mm00607939_s1), and fold change of gene expression in BMDM to bacterial challenge compared with medium alone control was determined using the ΔΔCt method (Schmittgen 2001).

Statistical analysis

For each experiment, BMDMs were derived from two mice, and each sample was run in duplicate. Data were pooled from two independent experiments and reported as the mean ± SEM. Comparisons between two data sets were performed using a Student's t-test. A P ≤ 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Both Porphyromonas gingivalis and Chlamydia pneumoniae induce foam cell formation in murine BMDM

We began by conducting a side-by-side foam cell formation assays following infection of BMDM with either P. gingivalis or C. pneumoniae, in the presence or absence of LDL. We observed a dose-dependent increase in oil red O staining with an increase in the MOI for each pathogen, but only in the presence of LDL (data not shown). BMDM cultured in LDL alone did not take on oil red O. From this, we determined that an MOI of 100 for P. gingivalis and an MOI of 10 for C. pneumoniae induced a comparable percentage of BMDM foam cells, while LDL alone treatment did not (Fig. 1). These infection MOIs were used for all subsequent studies.

Figure 1.

Foam cell formation in the presence of LDL in response to P. gingivalis and C. pneumoniae. Murine BMDM from C57BL-6 mice (n = 4) were cultured in the presence of human LDL (LDL; 200 μg ml−1) alone (A), LDL with P. gingivalis (MOI 100) (B) or LDL with C. pneumoniae (MOI 10) (C). After 24 h, BMDM were stained for foam cells as described in the Methods, and digital microscopic images were captured at 20× magnification. (D) Quantified data from counting 450 cells per visual field in five separate fields in a blinded manner. Data are reported as the mean ± SEM.

Infection induces inflammatory cytokine secretion during foam cell formation

Next we tested the ability of P. gingivalis and C. pneumoniae to induce the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines during macrophage foam cell formation. We found that both P. gingivalis and C. pneumoniae infection induce the secretion of TNF-α (Fig. 2A) and IL-6 (not shown) from infected LDL-treated BMDM, while only C. pneumoniae induced the secretion of IL-1β (Fig. 2B). This is consistent with our previous observation that C. pneumoniae is a potent activator of the inflammasome (He et al.2010) while P. gingivalis is not (Slocum et al.2014). Of note, cytokine secretion was much lower in the presence of LDL compared to infected macrophages without LDL (Fig. S1, Supporting Information), suggesting that LDL loading dampens the proinflammatory response to infection in macrophages. These data indicate that, although both P. gingivalis and C. pneumoniae induce an inflammatory cytokine profile in macrophages during foam cell formation, the specific cytokine response to each organism is not identical.

Figure 2.

Levels of TNF-α and IL1β production by BMDM in response to P. gingivalis and C. pneumoniae during foam cell formation. BMDM from C57BL-6 mice (n = 4) were cultured in the presence of human LDL (200 μg ml−1) alone, P. gingivalis (MOI 100), C. pneumoniae (MOI 10), LDL with P. gingivalis (MOI 100) or LDL with C. pneumoniae (MOI 10). Culture supernatants were collected after 24 h, and assayed for TNF-α (A) and IL1β (B) by ELISA. Data were pooled from two independent experiments and are reported as the mean ± SEM. *, P < 0.05 compared to control (LDL alone).

Lipid oxidation in response to Porphyromonas gingivalis and Chlamydia pneumoniae

LDL is susceptible to oxidation, and cellular oxidation of LDL is believed to be an important step in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis (reviewed in Steinberg 1997, 2009). Chlamydia pneumoniae has been shown to induce LDL oxidation in monocytes and endothelial cells (Kalayoglu et al.1999; Netea et al.2000; Dittrich et al.2004), although less is known about the effect of P. gingivalis on cellular LDL oxidation (Bengtsson et al.2008). To examine this further, we compared the levels of malondialdehydrate (MDA), a by-product of lipid peroxidation, as a surrogate marker for lipid oxidation, in the culture supernatants during macrophage foam cell formation in response to P. gingivalis and C. pneumoniae infection. We found significantly higher levels of lipid oxidation in response to both P. gingivalis and C. pneumoniae compared with the LDL alone control (Fig. 3). While there was the suggestion that C. pneumoniae induced higher levels of oxidation compared to P. gingivalis, this was not statistically significant. These results demonstrate that both P. gingivalis and C. pneumoniae induce oxidation of LDL during macrophage foam cell formation.

Figure 3.

Lipid peroxidation (MDA) levels in response to P. gingivalis and C. pneumoniae during BMDM foam cell formation. Murine BMDM from C57BL-6 mice (n = 4) were cultured in the presence of LDL (200 ug ml−1), LDL with P. gingivalis (MOI 100) or LDL with C. pneumoniae (MOI 10). After 24 h, culture supernatant fluids were collected and assayed for MDA. Data were pooled from two independent experiments and are reported as the mean ± SEM. *, P < 0.05 compared to control (LDL alone).

Atherosclerosis pathway gene regulation in response to Porphyromonas gingivalis and Chlamydia pneumoniae during macrophage foam cell formation

To define the signaling pathways regulated by P. gingivalis and C. pneumoniae during macrophage foam cell formation, we employed a mouse atherosclerosis pathway PCR array to examine the differential expression of 84 genes related to atherosclerosis during P. gingivalis or C. pneumoniae infection and foam cell formation. Genes with significant differential expression (2-fold change and P ≤ 0.05) in the treatment groups (LDL + P. gingivalis or LDL + C. pneumoniae) compared to the control group (LDL alone) are shown in Table 1 (upregulated genes) and Table 2 (downregulated genes), and Fig. 4. Among the 84 genes tested, 30 genes were significantly upregulated in terms of expression (Table 1), while only 6 genes were significantly downregulated (Table 2) in the two treatment groups. Interestingly, the number of differentially expressed genes common to the two pathogen-treated groups was substantially larger than the number specific to either pathogen-treated group. There were only six genes that could be described as specific to a particular pathogen. Further analysis was carried out for the genes involved in inflammation, lipid metabolism, apoptosis and adhesion (Table 3).

Table 1.

Upregulated genes during pathogen-induced macrophage foam cell formation.

| Pg | Cp | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene symbol | Gene name | Fold change | P value | Fold change | P value |

| Bcl2 | B-Cell leukemia/lymphoma 2 | 5.36 | 0.01 | 4.25 | 0 |

| Bcl2a1a | B-Cell leukemia/lymphoma 2 related protein A1a | 98.79 | 0 | 32.8 | 0 |

| Bcl2l1 | Bcl2-like 1 | 2.01 | 0.04 | 2.15 | 0 |

| Bid | BH3 interacting domain death agonist | 3.73 | 0 | 2.72 | 0 |

| Birc3 | Baculoviral IAP repeat-containing 3 | 4.8 | 0 | 2.94 | 0 |

| Ccl2 | Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2 | 53.02 | 0.01 | 113.75 | 0 |

| Ccl5 | Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 5 | 316.76 | 0 | 684.5 | 0 |

| Cflar | CASP8 and FADD-like apoptosis regulator | 8.03 | 0 | 6.67 | 0 |

| Cxcl1 | Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 1 | 7306.71 | 0.01 | 2777.27 | 0 |

| Fabp3 | Fatty acid binding protein 3, muscle and heart | 11.16 | 0 | 4.54 | 0 |

| Fas | Fas (TNF receptor superfamily member 6) | 5.69 | 0 | 3.95 | 0 |

| Icam1 | Intercellular adhesion molecule 1 | 10.29 | 0 | 10.6 | 0 |

| Il1a | Interleukin 1 alpha | 1184.19 | 0 | 775.14 | 0 |

| Il1b | Interleukin 1 beta | 1293.29 | 0 | 1089.13 | 0 |

| Itga5 | Integrin alpha 5 (fibronectin receptor alpha) | 4.49 | 0 | 4.76 | 0 |

| Ldlr | Low-density lipoprotein receptor | 2.63 | 0 | 2.08 | 0 |

| Lif | Leukemia inhibitory factor | 21.85 | 0 | 6.65 | 0 |

| Lpl | Lipoprotein lipase | 2.21 | 0.01 | 2.1 | 0.01 |

| Mmp1a | Matrix metallopeptidase 1a (interstitial collagenase) | 2.43 | 0.02 | 2.49 | 0.03 |

| Mmp3 | Matrix metallopeptidase 3 | 19.43 | 0.01 | 23.64 | 0 |

| Msr1 | Macrophage scavenger receptor 1 | 2.16 | 0 | 1.89 | 0 |

| Nfkb1 | Nuclear factor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B cells 1, p105 | 3.88 | 0 | 3.77 | 0 |

| Pdgfb | Platelet-derived growth factor, B polypeptide | 7.82 | 0 | 8.11 | 0 |

| Pdgfrb | Platelet-derived growth factor receptor, beta polypeptide | 4.71 | 0 | 1.74 | 0.01 |

| Ppard | Peroxisome proliferator activator receptor delta | 3.76 | 0 | 2.07 | 0 |

| Sele | Selectin, endothelial cell | 5.32 | 0.05 | 4.72 | 0.01 |

| Serpinb2 | Serine (or cysteine) peptidase inhibitor, clade B, member 2 | 29.61 | 0.02 | 17.57 | 0 |

| Tnf | Tumor necrosis factor | 182.22 | 0 | 110.3 | 0 |

| Tnfaip3 | Tumor necrosis factor, alpha-induced protein 3 | 56.68 | 0.01 | 43.29 | 0 |

| Vcam1 | Vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 | 43.51 | 0.01 | 68.3 | 0 |

Change compared to uninfected controls. Pg: P. gingivalis; Cp: C. pneumoniae.

Table 2.

Downregulated genes during pathogen-induced macrophage foam cell formation.

| Pg | Cp | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene symbol | Gene name | Fold change | P value | Fold change | P value |

| Ccr2 | Chemokine (C-C motif) receptor 2 | −6.54 | 0.03 | −4.69 | 0.03 |

| Ctgf | Connective tissue growth factor | −4.02 | 0.01 | −2.98 | 0.01 |

| Fgf2 | Fibroblast growth factor 2 | −7.38 | 0 | −4.94 | 0 |

| Pdgfa | Platelet derived growth factor, alpha | −2.51 | 0.02 | −3.4 | 0 |

| Ptgs1 | Prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 1 | −3.12 | 0.02 | −3.02 | 0.02 |

| Rxra | Retinoid X receptor alpha | −2.8 | 0.01 | −3.62 | 0 |

Change compared to uninfected controls. Pg: P. gingivalis; Cp: C. pneumoniae.

Figure 4.

Heat map representation of BMDM atherosclerosis pathway gene expressions in response to P. gingivalis and C. pneumoniae in foam cell formation. Murine BMDM from C57BL-6 mice (n = 4) were cultured in the presence of LDL (200 ug ml−1) alone (A), LDL with P. gingivalis (MOI 100) (B) or LDL with C. pneumoniae (MOI 10) (C). After 6 h, cells were lysed for RNA isolation and gene expression analysis was performed using the RT2 Profiler PCR Array Mouse Atherosclerosis Array (Qiagen). Relative mRNA expression was determined as described in the Methods. Shown above is the heat map representation of the expression of these genes. A = control LDL alone; B = P. gingivalis + LDL; C = C. pneumoniae + LDL.

Table 3.

Pathogen-specific gene regulation during macrophage foam cell formation.

| Gene symbol | Gene name | Fold change, Pg | Fold change, Cp |

|---|---|---|---|

| Itgax | Integrin alpha X | 2.17 | NS |

| Kdr | Kinase insert domain protein receptor | NS | 2.10 |

| Klf2 | Kruppel-like factor 2 (lung) | −4.74 | NS |

| Pparg | Peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma | NSa | −2.35 |

| Sell | Selectin, lymphocyte | NS | +3.57 |

| Tgfb1 | Transforming growth factor, beta 1 | NS | −1.28 |

| Vegfa | Vascular endothelial growth factor A | −5.97 | NS |

Change compared to uninfected controls, P-value ≤ 0.05; NS: not significant.

Both Pg and Cp treatment was found to downregulate Pparg gene expression by RT-PCR.

Pg: P. gingivalis; Cp: C. pneumoniae.

Expression of inflammation associated genes in response to Porphyromonas gingivalis and Chlamydia pneumoniae during macrophage foam cell formation

A number of cytokine and chemokine genes were significantly upregulated in response to P. gingivalis + LDL or C. pneumoniae + LDL treatment compared to LDL alone. This included the cytokines, Il1a, Il1b, Csf2, Tnfa and chemokines, Ccl2, Ccl5, Cxcl1. Expression of the CCL2 receptor gene, Ccr2, was significantly reduced by both pathogens, while there was no change in Ccr1. In the case of transforming growth factor (Tgfb) genes, Tgfb1 and Tgfb2, we observed reduced expression in response to C. pneumoniae + LDL treatment, although only the change in Tgfb1 reached significance. Similar levels were also observed in response to P. gingivalis. In addition, we observed a significant upregulation in two proinflammatory transcription factors, Nfkb1 and Tnfaip3, in response to treatment. Combined with the cytokine ELISA data, these results indicate that P. gingivalis and C. pneumoniae induced macrophage foam cell formation is associated with activation of proinflammatory signaling pathways.

Expression of genes associated with lipid metabolism in response to Porphyromonas gingivalis and Chlamydia pneumoniae during macrophage foam cell formation

We examined the expression of genes associated with the transport and metabolism of lipids during P. gingivalis and C. pneumoniae induced macrophage foam cell formation. Genes associated with lipid uptake, including Ldlr, Lpl and Msr1, were induced in response to P. gingivalis or C. pneumoniae treatment in the presence of LDL. In contrast, there was no difference in the expression of Abca1 or Apoe, genes involved in lipid efflux or secretion. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) are a family of nuclear hormone receptors that play an essential role in lipid and fatty acid metabolism. PPAR-γ is involved in adipocyte differentiation, while PPAR-α and PPAR-δ are regulators of fatty acid oxidation (reviewed in Fan and Evans 2015). We found that expression of Ppard was upregulated in response to both pathogens more than 2-fold. In contrast, expression of Pparg was reduced, while Ppara was not changed in a statistically significant manner. The gene for retinoid X receptor alpha (Rxra), another nuclear hormone receptor protein that forms heterodimers with PPAR-γ, was also reduced in response to P. gingivalis or C. pneumoniae. Collectively, these data suggest an upregulation of genes involved in lipid uptake as well as oxidation of lipids, concomitant with downregulation of genes involved in lipid efflux during pathogen-induced foam cell formation.

Expression of genes associated with apoptosis in response to Porphyromonas gingivalis and Chlamydia pneumoniae during macrophage foam cell formation

Apoptosis is a highly regulated process of cell death that is required for the development and homeostasis of multicellular organisms. We observed upregulation of both pro- and anti-apoptotic genes in response to P. gingivalis + LDL or C. pneumoniae + LDL treatment. For example, Bcl2 and Birc3, which block apoptotic death, were upregulated, while the death domain agonist Bid and the death receptor Fas (Tnfsf6) were also upregulated. The anti-apoptotic gene Klf2 was also downregulated in response to P. gingivalis but not C. pneumoniae (Table 3). Finally, a number of genes that can have either pro- or anti-apoptotic effects were increased, including the caspase-8-related gene Cflar and the Bcl2-related gene Bcl2l1. Thus, the effect of pathogen-induced foam cell formation on cell death, and specifically on apoptosis, is mixed, likely reflecting the complex effects of oxidized LDL and the pathogens themselves on cell death.

Expression of genes associated with cell adhesion and extracellular matrix modification in response to Porphyromonas gingivalis and Chlamydia pneumoniae during macrophage foam cell formation

Changes in the extracellular matrix have been linked to the development of atherosclerosis and atherosclerotic complications such as plaque rupture. We found expression of Icam1 and Vcam1, adhesion molecules also associated with inflammation (Galkina and Ley 2007), was strongly induced during both P. gingivalis (10- and 40-fold, respectively) and C. pneumoniae (10- and 68-fold, respectively) induced macrophage foam cell formation. Finally, Mmp3, a matrix metalloproteinase that can degrade the extracellular matrix and has been linked to atherosclerosis (Ye 2006), was strongly upregulated by P. gingivalis or C. pneumoniae treatment by approximately 20-fold compared to LDL alone. Porphyromonas gingivalis also upregulated Itgax, which encodes the adhesion molecule integrin alpha X, while C. pneumoniae upregulated the adhesion receptors Kdr and Sell (Table 3). Taken together, these results suggest that pathogen-induced foam cell formation modulates cell-cell and cell-extracellular matrix interactions that could lead to more inflammatory and more unstable plaque formation.

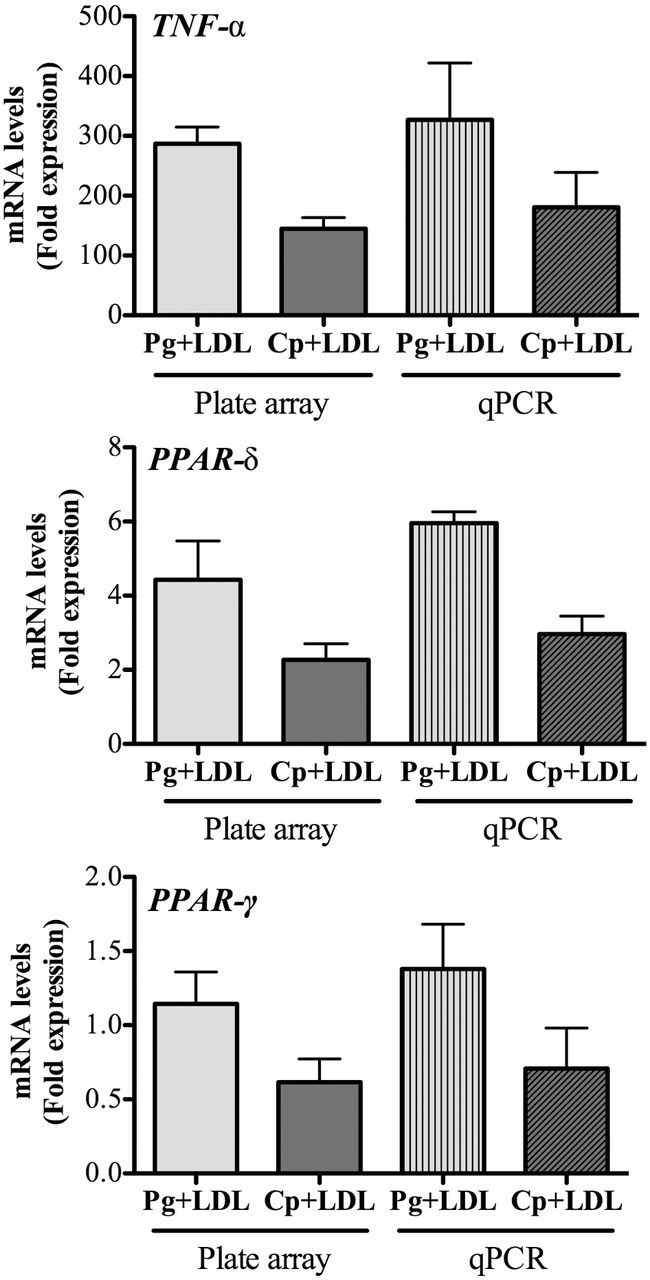

qRT-PCR and cytokine confirmation of atherosclerosis plate array

Differential expression of a small subset of genes from the PCR array, Tnfa, Ppard and Pparg, was confirmed using qRT-PCR (Fig. 5). Expression of Pparg was found to be decreased in both P. gingivalis and C. pneumoniae induced foam cells by RT-PCR, while the array only identified the change in response to C. pneumoniae using our cut-off criteria for significance. Finally, the TNF-α ELISA data (Fig. 2) also validated the change in Tnfa mRNA expression. Although some variation was present, these data suggest that overall there was general agreement in data using three assay systems.

Figure 5.

Quantitative real-time PCR verification of microarray mRNA expression. Quantitative real-time PCR was performed on cDNA generated from RNA employed in the microarrays using gene specific Taqman assays normalized to β-actin gene expression, as described in the Methods. Shown above are the results for expression of (A) Tnfa (B), Ppard and (C) Pparg. Relative gene expression from plate array is shown for comparison. Data are presented as mean ± SEM of two independent experiments that were pooled. No significant differences between LDL control and LDL+P. gingivalis or LDL+ C. pneumoniae groups were observed (P > 0.05).

DISCUSSION

Porphyromonas gingivalis and Chlamydia pneumoniae are important human pathogens that, in addition to their association with periodontal disease and pneumonia, respectively, have been linked to systemic inflammatory conditions such as atherosclerosis. While each agent has been studied independently, this is the first study to examine the effects of live bacteria on gene regulation side-by-side during macrophage foam cell induction. Their shared ability to invade macrophages and activate a variety of inflammatory pathways likely represents a common mechanism driving foam cell formation in spite of the fact that they utilize different receptors and have quite divergent lifestyles. Macrophages play a key role in the innate immune response to pathogenic microorganisms. Moreover, they are central players in the development, progression and regression of atherosclerosis (reviewed in Moore, Sheedy and Fisher 2013). We found that both P. gingivalis and C. pneumoniae infection of macrophages, in the presence of LDL, induced foam cell formation in BMDM in a dose-dependent manner; we also observed a concomitant induction of LDL oxidation during infection, likely a key step in atherosclerosis.

Foam cell formation in response to these two pathogens clearly initiates a proinflammatory response, as noted by the increased transcription of inflammation-associated genes, including cytokines, chemokines and transcription factors, as well as the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-6. However, there is redundancy in the inflammatory signaling as mature IL-1β secretion is not critical to foam cell formation in response to P. gingivalis. It is interesting to note that the presence of LDL blunted the secretion of infection-elicited cytokine production by BMDMs. Although Blessing et al. (2002) did not observe a similar effect of LDL on cytokine production, they used a lower concentration of LDL and RAW macrophages instead of primary BMDM. Our data are more consistent with the recent report by Kannan et al. (2012), who observed that oxidized LDL inhibits the response to TLR2 and TLR4 ligands in human monocytes.

The inflammatory signaling pathways initiated by these pathogens were likely key to the subsequent alterations in genes involved in lipid uptake and lipid metabolism observed in the macrophages. For example, the increased expression of genes involved in lipid uptake, with no significant change in genes involved in lipid efflux, would be expected to lead to a net increase in cellular lipid content within the macrophages. Regulation of the PPAR family members and their binding partners is notable, as these ligand-activated transcription factors sense inflammation and oxidative stress, and are major regulators of lipid, glucose and amino acid metabolism particularly during tissue injury and repair (reviewed in Michalik et al.2006). We observed reduced expression of both Pparg and its binding partner, Rxra, during pathogen-induced foam cell formation. PPAR-γ ligands have anti-inflammatory and anti-proliferative effects (reviewed in Duan, Usher and Mortensen 2009; Takano and Komuro 2009), and activation of PPAR-γ and RXR-α has been shown to inhibit foam cell formation in macrophages exposed to oxidized LDL through cholesterol efflux (Argmann et al.2003). Thus, our observed reduction in PPAR-γ gene expression by BMDMs on pathogen exposure correlates with increased atherosclerosis risk, and thus may be an important target point for future assessments in the context of pathogen-associated atherosclerosis. Moreover, PPAR-γ is a key regulator of glucose homeostasis and adipogenesis, and PPAR-γ agonists have been used in the treatment of type 2 diabetes (Feige et al.2006; Sugden, Zariwala and Holness 2009). The effects of pathogen-induced foam cell formation on apoptosis pathway genes were more complex, with upregulation of both pro- and anti-apoptotic genes noted, perhaps reflecting the competing needs of an intracellular pathogen with the host response (Seimon and Tabas 2009). More recently, decreased PPAR-γ expression in macrophages and smooth muscle cells has been linked to disease progression in patients with carotid atherosclerosis (Giaginis et al.2011), suggesting that it, too, could be an important target in the treatment of atherosclerosis. This approach could benefit pathogen-accelerated atherosclerotic disease as well.

The increased expression of matrix remodeling genes, such as Mmp3, and adhesion molecules, including Icam1 and Vcam1, suggest that pathogen-induced foam cell formation can alter both cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions. This could impact recruitment of inflammatory cells such as monocytes and T- and B-lymphocytes to the sites of fatty streaks and atherosclerotic lesions. In addition, we identified a number of genes in common with the report from Chen et al. (2013), which described a gene set associated with unstable plaque. For example, we observed increased expression of Ccl2 (also known as MCP-1), Il1b and Pdgf in our plate array during pathogen-induced foam cell formation. Although Mmp9 and Mmp12 were not part of the array, we did see increased expression of Mmp1a and Mmp3 under our conditions. Thus, our data would suggest that pathogen-induced foam cell formation can lead to unstable plaque which would be at increased risk for plaque rupture.

Finally, our data were somewhat surprising in that we did not identify a set of genes that could define unique genes or pathways utilized by either pathogen associated with foam cell induction. While there were five genes determined to be differentially regulated (Itgax, Kdr, Klf2, Sell and Vegfa), none were specific to a pathway that we would consider pathogen specific, reinforcing the shared mechanism utilized by these two divergent bacterial species. Although we did not test an exhaustive group of bacteria and other infections with reported association with atherosclerosis, our data utilizing two organisms with uniquely distinct life cycles and host niches, interestingly, suggest that at the level of the macrophage, an array of similarities exist by which these cells respond to bacteria during foam cell formation. This suggests that it would be possible to target shared pathways as a therapeutic approach to fighting atherosclerosis. Our data are however limited by the use of foam cells differentiated from murine BMDM in vitro, as well as analysis at a single time point, which might not be optimal for the divergent lifestyles of these two pathogens. Thus, future studies should be directed at studying foam cell formation in vivo to better understand the interaction with environmental signals in a complex tissue.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the BU Analytical Instrumentation Core for assistance with the PCR Pathway Array

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

FUNDING

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants AI078894 (FCG and RRI) and DE024275 (FCG).

Conflict of interest. None declared.

REFERENCES

- Argmann CA, Sawyez CG, McNeil CJ, et al. Activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma and retinoid X receptor results in net depletion of cellular cholesteryl esters in macrophages exposed to oxidized lipoproteins. Arterioscl Thromb Vas. 2003;23:475–82. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000058860.62870.6E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer MT, Huang N, Gibson FC., 3rd Scavenger receptor A is expressed by macrophages in response to Porphyromonas gingivalis, and participates in TNF-alpha expression. Oral Microbiol Immun. 2009;24:456–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302X.2009.00538.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bengtsson T, Karlsson H, Gunnarsson P, et al. The periodontal pathogen Porphyromonas gingivalis cleaves apoB-100 and increases the expression of apoM in LDL in whole blood leading to cell proliferation. J Intern Med. 2008;263:558–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2007.01917.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blessing E, Kuo CC, Lin TM, et al. Foam cell formation inhibits growth of Chlamydia pneumoniae but does not attenuate Chlamydia pneumoniae-induced secretion of proinflammatory cytokines. Circulation. 2002;105:1976–82. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000015062.41860.5b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell LA, Kuo CC. Chlamydia pneumoniae—an infectious risk factor for atherosclerosis? Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2:23–32. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Shimada K, Zhang W, et al. IL-17A is proatherogenic in high-fat diet-induced and Chlamydia pneumoniae infection-accelerated atherosclerosis in mice. J Immunol. 2010;185:5619–27. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YC, Bui AV, Diesch J, et al. A novel mouse model of atherosclerotic plaque instability for drug testing and mechanistic/therapeutic discoveries using gene and microRNA expression profiling. Circ Res. 2013;113:252–65. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.301562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu B. Multiple infections in carotid atherosclerotic plaques. Am Heart J. 1999;138:S534–6. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(99)70294-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Pietro M, Filardo S, De Santis F, et al. Chlamydia pneumoniae infection in atherosclerotic lesion development through oxidative stress: a brief overview. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14:15105–20. doi: 10.3390/ijms140715105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dittrich R, Dragonas C, Mueller A, et al. Endothelial Chlamydia pneumoniae infection promotes oxidation of LDL. Biochem Bioph Res Co. 2004;319:501–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.04.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan SZ, Usher MG, Mortensen RM. PPARs: the vasculature, inflammation and hypertension. Curr Opin Nephrol Hy. 2009;18:128–33. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e328325803b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan W, Evans R. PPARs and ERRs: molecular mediators of mitochondrial metabolism. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2015;33:49–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2014.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feige JN, Gelman L, Michalik L, et al. From molecular action to physiological outputs: peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors are nuclear receptors at the crossroads of key cellular functions. Prog Lipid Res. 2006;45:120–59. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galkina E, Ley K. Vascular adhesion molecules in atherosclerosis. Arterioscl Thromb Vas. 2007;27:2292–301. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.149179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giacona MB, Papapanou PN, Lamster IB, et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis induces its uptake by human macrophages and promotes foam cell formation in vitro. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2004;241:95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.femsle.2004.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giaginis C, Klonaris C, Katsargyris A, et al. Correlation of Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor-gamma (PPAR-gamma) and Retinoid X Receptor-alpha (RXR-alpha) expression with clinical risk factors in patients with advanced carotid atherosclerosis. Med Sci Monitor. 2011;17:CR381–91. doi: 10.12659/MSM.881849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson FC, 3rd, Hong C, Chou HH, et al. Innate immune recognition of invasive bacteria accelerates atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Circulation. 2004;109:2801–6. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000129769.17895.F0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson FC, 3rd, Ukai T, Genco CA. Engagement of specific innate immune signaling pathways during Porphyromonas gingivalis induced chronic inflammation and atherosclerosis. Front Biosci. 2008;13:2041–59. doi: 10.2741/2822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson FC, 3rd, Yumoto H, Takahashi Y, et al. Innate immune signaling and Porphyromonas gingivalis-accelerated atherosclerosis. J Dent Res. 2006;85:106–21. doi: 10.1177/154405910608500202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammerschlag MR. Chlamydia pneumoniae and the lung. Eur Respir J. 2000;16:1001–7. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00.16510010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haraszthy VI, Zambon JJ, Trevisan M, et al. Identification of periodontal pathogens in atheromatous plaques. J Periodontol. 2000;71:1554–60. doi: 10.1902/jop.2000.71.10.1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X, Mekasha S, Mavrogiorgos N, et al. Inflammation and fibrosis during Chlamydia pneumoniae infection is regulated by IL-1 and the NLRP3/ASC inflammasome. J Immunol. 2010;184:5743–54. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishihara K, Nabuchi A, Ito R, et al. Correlation between detection rates of periodontopathic bacterial DNA in coronary stenotic artery plaque [corrected] and in dental plaque samples. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:1313–5. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.3.1313-1315.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi R, Khandelwal B, Joshi D, et al. Chlamydophila pneumoniae infection and cardiovascular disease. N Am J Med Sci. 2013;5:169–81. doi: 10.4103/1947-2714.109178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalayoglu MV, Byrne GI. Induction of macrophage foam cell formation by Chlamydia pneumoniae. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:725–9. doi: 10.1086/514241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalayoglu MV, Hoerneman B, LaVerda D, et al. Cellular oxidation of low-density lipoprotein by Chlamydia pneumoniae. J Infect Dis. 1999;180:780–90. doi: 10.1086/314931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalayoglu MV, Indrawati, Morrison RP, et al. Chlamydial virulence determinants in atherogenesis: the role of chlamydial lipopolysaccharide and heat shock protein 60 in macrophage-lipoprotein interactions. J Infect Dis. 2000;181(Suppl 3):S483–9. doi: 10.1086/315619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kannan Y, Sundaram K, Aluganti Narasimhulu C, et al. Oxidatively modified low density lipoprotein (LDL) inhibits TLR2 and TLR4 cytokine responses in human monocytes but not in macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:23479–88. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.320960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer CD, Weinberg EO, Gower AC, et al. Distinct gene signatures in aortic tissue from ApoE−/− mice exposed to pathogens or Western diet. BMC Genomics. 2014;15:1176. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-1176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Hammerschlag MR. Acute respiratory infection due to Chlamydia pneumoniae: current status of diagnostic methods. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:568–76. doi: 10.1086/511076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo CC, Shor A, Campbell LA, et al. Demonstration of Chlamydia pneumoniae in atherosclerotic lesions of coronary arteries. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:841–9. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.4.841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Messas E, Batista EL, Jr, et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis infection accelerates the progression of atherosclerosis in a heterozygous apolipoprotein E-deficient murine model. Circulation. 2002;105:861–7. doi: 10.1161/hc0702.104178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maekawa T, Takahashi N, Tabeta K, et al. Chronic oral infection with Porphyromonas gingivalis accelerates atheroma formation by shifting the lipid profile. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20240. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michalik L, Auwerx J, Berger JP, et al. International union of pharmacology. LXI. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 2006;58:726–41. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.4.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore KJ, Sheedy FJ, Fisher EA. Macrophages in atherosclerosis: a dynamic balance. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:709–21. doi: 10.1038/nri3520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mysak J, Podzimek S, Sommerova P, et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis: major periodontopathic pathogen overview. J Immunol Res. 2014;2014:476068. doi: 10.1155/2014/476068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naiki Y, Sorrentino R, Wong MH, et al. TLR/MyD88 and liver X receptor alpha signaling pathways reciprocally control Chlamydia pneumoniae-induced acceleration of atherosclerosis. J Immunol. 2008;181:7176–85. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.10.7176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Netea MG, Dinarello CA, Kullberg BJ, et al. Oxidation of low-density lipoproteins by acellular components of Chlamydia pneumoniae. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:1868–70. doi: 10.1086/315460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ossewaarde JM, de Vries A, Bestebroer T, et al. Application of a Mycoplasma group-specific PCR for monitoring decontamination of Mycoplasma-infected Chlamydia sp. strains. Appl Environ Microb. 1996;62:328–31. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.2.328-331.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi M, Miyakawa H, Kuramitsu HK. Porphyromonas gingivalis induces murine macrophage foam cell formation. Microb Pathog. 2003;35:259–67. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2003.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmittgen TD. Real-time quantitative PCR. Methods. 2001;25:383–5. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012;9:671–5. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seimon T, Tabas I. Mechanisms and consequences of macrophage apoptosis in atherosclerosis. J Lipid Res. 2009;50(Suppl):S382–7. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800032-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaik-Dasthagirisaheb YB, Huang N, Baer MT, et al. Role of MyD88-dependent and MyD88-independent signaling in Porphyromonas gingivalis-elicited macrophage foam cell formation. Mol Oral Microbiol. 2013;28:28–39. doi: 10.1111/omi.12003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada K, Crother TR, Arditi M. Innate immune responses to Chlamydia pneumoniae infection: role of TLRs, NLRs, and the inflammasome. Microbes Infect. 2012;14:1301–7. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2012.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slocum C, Coats SR, Hua N, et al. Distinct lipid a moieties contribute to pathogen-induced site-specific vascular inflammation. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1004215. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg D. Low density lipoprotein oxidation and its pathobiological significance. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:20963–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.34.20963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg D. The LDL modification hypothesis of atherogenesis: an update. J Lipid Res. 2009;50(Suppl):S376–81. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800087-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugden MC, Zariwala MG, Holness MJ. PPARs and the orchestration of metabolic fuel selection. Pharmacol Res. 2009;60:141–50. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2009.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takano H, Komuro I. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma and cardiovascular diseases. Circ J. 2009;73:214–20. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-08-1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor-Robinson D, Thomas BJ. Chlamydia pneumoniae in atherosclerotic tissue. J Infect Dis. 2000;181(Suppl 3):S437–40. doi: 10.1086/315614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye S. Influence of matrix metalloproteinase genotype on cardiovascular disease susceptibility and outcome. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;69:636–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.