Abstract

Townes-Brocks syndrome (TBS) is characterized by a spectrum of malformations in the digits, ears, and kidneys. These anomalies overlap those seen in a growing number of ciliopathies, which are genetic syndromes linked to defects in the formation or function of the primary cilia. TBS is caused by mutations in the gene encoding the transcriptional repressor SALL1 and is associated with the presence of a truncated protein that localizes to the cytoplasm. Here, we provide evidence that SALL1 mutations might cause TBS by means beyond its transcriptional capacity. By using proximity proteomics, we show that truncated SALL1 interacts with factors related to cilia function, including the negative regulators of ciliogenesis CCP110 and CEP97. This most likely contributes to more frequent cilia formation in TBS-derived fibroblasts, as well as in a CRISPR/Cas9-generated model cell line and in TBS-modeled mouse embryonic fibroblasts, than in wild-type controls. Furthermore, TBS-like cells show changes in cilia length and disassembly rates in combination with aberrant SHH signaling transduction. These findings support the hypothesis that aberrations in primary cilia and SHH signaling are contributing factors in TBS phenotypes, representing a paradigm shift in understanding TBS etiology. These results open possibilities for the treatment of TBS.

Keywords: SALL1, spalt, BioID, primary cilia, rare disease, Townes-Brocks syndrome

Introduction

Townes-Brocks syndrome (TBS1 [MIM: 107480]) is characterized by the presence of an imperforate anus and dysplastic ears and is frequently associated with sensorineural and/or conductive hearing impairment and thumb malformations such as triphalangy, duplications (preaxial polydactyly), and hypoplasia.1 Common features among TBS individuals include end-stage renal disease, polycystic kidneys, foot and genitourinary malformations, and congenital heart disease. Although less common, short ribs, intellectual disability, growth retardation, cleft palate, and eye defects are also observed. TBS is an autosomal-dominant genetic disease caused by mutations in SALL1 (SAL-like 1 [MIM: 602218]),2, 3 one of the four members of the SALL gene family in vertebrates. SALL1 encodes a zinc-finger transcription factor linked to chromatin-mediated repression.4 SALL1 is characterized by the presence of stereotypical pairs of zinc-finger domains along the protein, which are thought to mediate interactions with DNA via an AT-rich sequence.5 In vertebrates, the N-terminal region of SALL1 mediates transcriptional repression via its interaction with the nucleosome-remodeling deacetylase (NuRD) complex6 as well as containing a polyglutamine domain involved in dimerization with itself or other SALL family members.7

Dominant genetic syndromes are often caused by a gain-of-function or dominant-negative effect of the underlying mutant proteins. Many TBS-causing SALL1 mutations could result in truncated proteins that lack most of the zinc finger pairs likely to mediate chromatin-DNA interactions but retain the N-terminal domain. In fact, this region represents a mutational “hotspot” where many nonsense mutations and deletions causing frameshifts have been described.3 Mutant SALL1 mRNA transcripts are stable and resistant to nonsense-mediated decay,8 and the resulting truncated proteins are able to interact with the NuRD complex and perhaps other factors, as well as form dimers with themselves, with full-length SALL1 (SALL1FL), or with other SALL proteins.9 Sall1+/− and Sall1−/− mice fail to show TBS-like phenotypes,10, 11, 12 discarding haploinsufficiency as the most plausible cause of the disease. Only when murine Sall1 is altered to mimic human mutations (i.e., to generate a truncated protein in a single copy) do mice display TBS symptoms, such as hearing loss and anus and limb malformations.11 Because TBS depends on the presence of a truncated SALL1, elucidating its role and its possible interference with SALL1FL and other factors would fill a major gap in our understanding of TBS.

Intriguingly, some TBS features match those seen in ciliopathies, diseases linked to the function of primary cilia.13 Ciliopathies present a spectrum of overlapping phenotypes such as polycystic kidneys, hearing loss, limb defects, and mental retardation, among others. These coincidental features could suggest similar cellular and molecular underpinnings between ciliopathies and TBS.

Cilia are microtubule-based organelles that emerge from centriole-containing basal bodies. Centrioles, together with their surrounding matrix, the pericentriolar material, form the centrosome. Once anchored to the plasma membrane, centrioles behave as basal bodies, giving rise to two different kinds of cilia: motile cilia (or flagella) and primary cilia. Non-motile primary cilia are present in most vertebrate cells,14 and ciliary assembly and disassembly are coordinated during the cell cycle.15, 16 Primary cilia arise from the mother centriole (MC) upon entry into the G0 phase, reabsorb as cells progress from the G1 to the S phase, and completely disassemble in mitosis.17 Cilia assembly is tightly controlled by essential proteins that contribute to structure and transport to, from, or within the cilia and counterbalanced with negative regulators. Primary cilia have a crucial role in cell signaling, polarity, and protein trafficking. During development, the vertebrate Sonic Hedgehog (SHH) pathway is crucial for vertebrate digit patterning and is fully dependent on primary cilia.18, 19 In brief, SHH activation through its receptor PTCH1 leads to ciliary enrichment of the transmembrane protein Smoothened (SMO) and a concomitant conversion of the transcription factor GLI3 from a repressor to an activator, leading to activation of SHH target genes, such as GLI1 (GLI family zinc finger 1 [MIM: 165220]) and PTCH1 (patched 1 [MIM: 601309]). The trafficking through primary cilia is tightly regulated by several anterograde and retrograde systems.20, 21 Mutations in genes that encode intraflagellar transport proteins deregulate SHH signaling and result in limb and neural-tube-closure defects, phenotypes similar to those resulting from mutations of genes encoding SHH pathway components.22, 23, 24

Here, we show that TBS-derived primary fibroblasts exhibit changes in SALL1FL localization, a higher rate of ciliogenesis, abnormally elongated cilia, aberrant cilia disassembly, and SHH signaling defects. Through proximity proteomics, we identified two main ciliogenesis suppressors, CCP110 (centriolar coiled-coil protein of 110 kDa) and CEP97 (centrosomal protein of 97 kDa), as interactors of TBS-causing truncated SALL1. The higher rate of ciliogenesis detected in TBS-derived fibroblasts is consistent with an observed lower amount of CCP110 and CEP97 at the MC in these fibroblasts than in controls.

Furthermore, truncated SALL1, alone or in complex with SALL1FL, interacts with CCP110 and CEP97 in the cytoplasm of individual-derived fibroblasts, which most likely leads to a reduction of CCP110 and CEP97 at the MC by sequestration. These results indicate that truncated proteins arising from certain SALL1 mutations can disrupt cilia formation and function. Therefore, TBS might be considered a ciliopathy-like disease.

Material and Methods

Cell Culture

TBS-derived primary fibroblasts, mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs), HEK293FT cells (Invitrogen), U2OS cells (ATCC HTB-96), and mouse Shh-LIGHT2 cells25 were cultured at 37°C and 5% CO2 in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; GIBCO) and 1% penicillin and streptomycin (GIBCO). Human TERT-RPE1 cells (ATCC CRL-4000) were cultured in DMEM/F12 (GIBCO) supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin and streptomycin. Dermal fibroblasts carrying a SALL1 c.995delC mutation, which produces a truncated p.Pro332Hisfs∗10 protein, were derived from male TBS individual OX3335 (TBSp.Pro332Hisfs∗10 herein).3, 8 Dermal fibroblasts carrying the SALL1 pathogenic variant c.826C>T, which produces a truncated p.Arg276∗ protein, were derived from male TBS individual UKTBS#3 (TBSp.Arg276∗ herein). Human neonatal foreskin fibroblasts (HFFs; ATCC CRL-2429) and adult female dermal fibroblasts (ESCTRL#2) from healthy donors were used as controls. We derived MEFs from wild-type (WT) and three heterozygous embryos carrying the Sall1-ΔZn2–10 mutant allele.11 All the embryos were at embryonic day 13. WT and mutant alleles were detected by PCR genotyping using established methods. Cultured cells were maintained between 10 and 20 passages, tested for senescence by γ-H2AX staining, and grown until confluence (6-well plates for RNA extraction and western blot assays; 10 cm dishes for pull-downs). Most cells were transfected with calcium phosphate, but primary fibroblasts were transfected with Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen). To induce primary cilia, we starved cells for 24 or 48 hr (DMEM, 0.1% FBS, 1% penicillin, and streptomycin). In the case of HEK293FT cells, we followed the conditions recently reported.26 The use of human samples in this study was approved by the ethics committee at CIC bioGUNE, and appropriate informed consent was obtained from human subjects. Work with mouse embryos to derive MEFs was approved by Saint Louis University. All experiments conformed to the relevant regulatory standards.

Plasmid Construction

A full-length (FL) human SALL1 clone was used for high-fidelity PCR amplification and subcloning into EYFP-N1 (Clontech) as truncated (SALL1c.826C>T-YFP) or FL (SALL1FL-YFP) versions. Clones, corresponding to current annotations, were validated by Sanger sequencing (GenBank: NM_002968.2). We exchanged EYFP for two copies of the HA tag to build SALL1FL-2xHA. For BioID vectors, Ac5-STABLE2-neo27 was modified to contain a CAG promoter, a Myc-tagged version of BirA (R118G, human codon optimized), and a multiple cloning site into which SALL1c.826C>T or SALL1FL was inserted.28 Lentiviral expression vectors were prepared in Lentilox-GFS-IRESpuro, a derivative of LL3.7 (GFS = GFP-FLAG-STREP).29

SALL1 Proximity Proteomics

With the BioID method,28 proteins in close proximity to SALL1 were biotinylated by fusion to a promiscuous form of the enzyme BirA (BirA∗) and isolated by streptavidin-bead pull-downs. Myc-BirA∗-SALL1c.826C>T or Myc-BirA∗-SALL1FL was transfected in HEK293FT cells (five 10 cm dishes per condition). 24 hr after transfection, medium was supplemented with biotin at 50 μM. Cells were collected after 48 hr, washed three times on ice with cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and scraped in lysis buffer (8 M urea, 1% SDS, 1× protease inhibitor cocktail [Roche], and 1× PBS; 1 mL per 10 cm dish). At room temperature, samples were sonicated and cleared by centrifugation. Cell lysates were incubated overnight with 40 μL of equilibrated NeutrAvidin-agarose beads (Thermo Scientific). Beads were subjected to stringent washes using the following washing buffers (WBs), all prepared in PBS: WB1 (8 M urea and 0.25% SDS), WB2 (6 M guanidine-HCl), WB3 (6.4 M urea, 1 M NaCl, and 0.2% SDS), WB4 (4 M urea, 1 M NaCl, 10% isopropanol, 10% ethanol, and 0.2% SDS), WB5 (8 M urea and 1% SDS), and WB6 (2% SDS). For elution of biotinylated proteins, beads were heated at 99°C in 50 μL of elution buffer (4× Laemmli buffer and 100 mM DTT). Beads were separated by centrifugation (18,000 × g for 5 min) or alternatively removed by centrifugation through a 0.8 μm filter (Vivaspin, Sartorius). Samples were used for mass spectrometry (MS) analysis as well as for western blotting for validation of selected candidates.

Mass Spectrometry

Three independent pull-down experiments were analyzed by MS. Samples eluted from the NeutrAvidin beads were separated in SDS-PAGE and stained with Brilliant Blue G-Colloidal Concentrate (Sigma) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The entire gel lanes were excised, divided into pieces, and destained, and proteins were reduced and alkylated before being in situ digested with trypsin. The resulting peptide mixtures were extracted, concentrated, and analyzed with an EASY nLC system (Proxeon). Peptides were ionized with a Proxeon ion source and sprayed directly into the mass spectrometer (Q-Exactive, Thermo Scientific). MaxQuant software (version 1.4.0.3) was used for the processing and analysis of recorded liquid chromatography tandem MS (LC-MS/MS) raw files with default parameters and applying a 1% false-discovery rate at both the peptide and protein levels. Label-free quantitation based on summed extracted peptide ion chromatograms was used for identifying differentially interacting proteins.

The lists of proteins identified by LC-MS/MS were analyzed as follows: only proteins identified by more than one peptide and present in at least two out of the three experiments were considered for analysis. Protein IDs were ranked according to the number of peptides found and their corresponding intensities. Hits were classified into those that interact with both FL and truncated SALL1p.Arg276∗ and those interacting preferentially with one or the other. A threshold of 2-fold change in iBAQ (intensity-based absolute quantification) value was considered significant. For each experiment, calculation took into account a baseline that corresponded to the minimum value of iBAQ registered for every specific sample.

Enrichment of Gene Ontology (GO) terms was analyzed with g:Cocoa, a tool integrated in the g:Profiler web server.30 GO enrichment was obtained by calculation of the −log10 of the p value.

Western Blot Analysis

Cells were lysed in cold RIPA buffer supplemented with 1× protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche). Lysates were kept on ice for 30 min with vortexing every 5 min and then cleared by centrifugation (25,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C). Supernatants were collected, and protein contents were quantified by a BCA protein quantification assay (Pierce). After SDS-PAGE and transfer to nitrocellulose or polyvinylidene fluoride, membranes were blocked in 5% milk in 1× PBS and 0.1% Tween-20. For anti-biotin, blocking was performed in casein. In general, primary antibodies were applied overnight at 4°C, and secondary antibodies were applied for 1 hr at room temperature. Antibodies used included CCP110 (Proteintech; 1:1,000), CEP97 (Proteintech; 1:1,000), Biotin (Biotin-HRP Cell Signaling; 1:2,000), HA (Sigma; 1:1,000), GFP (Roche; 1:1,000), tubulin-HRP (Proteintech; 1:2,000), GAPDH-HRP (Proteintech; 1:1,000), and Actin (Sigma; 1:1,000). The anti-SALL1 antibodies used detect specifically SALL1FL (R&D; aa 258–499) or the N-terminal part of SALL1.6 Secondary antibodies were HRP-conjugated anti-mouse or anti-rabbit (Jackson Immunoresearch). Proteins were detected with Clarity ECL (BioRad) or Super Signal West Femto (Pierce). Quantification of bands was performed with ImageJ software and normalized against actin or GAPDH levels. At least three independent blots were quantified per experiment.

GFP Pull-Downs

All steps were performed at 4°C. HEK293FT-transfected cells were collected after 48 hr, washed three times with 1× PBS, and lysed in 1 mL of lysis buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% NP-40, 0.5% Triton X-100, 5% glycerol, and protease inhibitors [Roche]). Lysates were kept on ice for 30 min with vortexing every 5 min and spun down at 25,000 × g for 20 min. After 40 μL of supernatant (input) was saved, the rest was incubated overnight with 30 μL of pre-washed GFP-Trap resin (Chromotek) in a rotating wheel. Beads were washed five times for 5 min each with WB (25 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 300 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% NP-40, 0.5% Triton X-100, and 5% glycerol). Beads were centrifuged at 2,000 × g for 2 min after each wash. For elution, samples were boiled for 5 min at 95°C in 2× Laemmli buffer.

Immunoprecipitation

All steps were performed at 4°C. HEK293FT-transfected cells were collected after 48 hr, washed 3 times with 1× PBS, and lysed in 1 mL of lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 137 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 1% NP-40, 5% glycerol, and protease inhibitor mixture [Roche]). Lysates were processed as described for GFP pull-downs. The rest was incubated overnight with 1 μg of CCP110 or CEP97 antibody (Proteintech) and for an additional 4 hr with 40 μL of pre-washed Protein G Sepharose 4 Fast Flow beads (GE Healthcare) in a rotating wheel. Beads were washed five times for 5 min each with WB (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 137 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 1% Triton X-100). Beads were centrifuged at 2,000 × g for 2 min after each wash. For elution, samples were boiled for 5 min at 95°C in 2× Laemmli buffer.

Immunostaining

hTERT-RPE cells, U2OS cells, and primary fibroblasts from control and TBS individuals were seeded on 11 mm coverslips (25,000 cells per well on a 24-well plate). We plated HEK293FT cells on coverslips coated with 0.01% poly-L-lysine (Sigma) to enhance adhesion. After being washed three times with cold 1× PBS, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA), 0.1% Triton X-100 in 1× PBS for 20 min on ice, and then washed three times with 1× PBS or pre-permeabilized for 2 min in PTEM buffer (20 mM PIPES [pH 6.8], 0.2% Triton X-100, 10 mM EGTA, and 1 mM MgCL2)31 and fixed for 10 min with 4% PFA for centrosomal staining. Blocking was performed for 1 hr at 37°C in blocking buffer (BB: 2% fetal calf serum and 1% BSA in 1× PBS). Primary antibodies were incubated overnight at 4°C, and cells were washed with 1× PBS three times. To label the ciliary axoneme as well as the basal body and pericentriolar regions, we used mouse antibodies against acetylated alpha-tubulin (Sigma) and gamma-tubulin (Sigma) or rabbit antibodies against ARL13B (Proteintech) and pericentrin (Covance; 1:160). Other antibodies included were mouse anti-SALL1 (R&D; 1:100), rabbit anti-CCP110 (Proteintech; 1:100), rabbit anti-CEP97 (Proteintech; 1:100), mouse monoclonal anti-CEP164 (Genetex; 1:100), rabbit anti-ODF2 (Atlas; 1:100), and mouse anti-phospho-Histone H2A.X (Millipore; 1:500).

Donkey anti-mouse or anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (Jackson Immunoresearch) conjugated to Alexa 488 or 568 (1:200) were incubated for 1 hr at 37°C and then nuclear stained with DAPI (Sigma; 10 min; 300 ng/mL in PBS). Transfected HEK293FT cells with Myc-BirA∗-SALL1c.826C>T or Myc-BirA∗-SALL1FL were incubated with 50 μM biotin for 24 hr, washed, fixed, and stained with Alexa-594-conjugated Streptavidin (Jackson Immunoresearch; 1:100). Fluorescence imaging was performed with an upright fluorescent microscope (Axioimager D1, Zeiss) or confocal microscope (Leica SP2) with a 40×, 63×, or 100× objective. For cilia measurements and counting, primary cilia from at least 15 different fluorescent micrographs from each experimental condition were analyzed with the ruler tool from Adobe Photoshop. We calculated cilia frequency by dividing the number of total cilia by the number of cells on each micrograph. The number of cells per micrograph was similar in both TBS and control fibroblasts. To obtain the level of fluorescence in a determined region, we calculated the corrected total cell fluorescence as previously described32 by using parameters obtained by ImageJ.

qPCR Analysis

TBSp.Pro332Hisfs∗10 and control fibroblasts were starved for 24 hr, and then they were either treated or not with purmorphamine for 24 or 48 hr (while starvation conditions were maintained) to induce the SHH signaling pathway. Total RNA was obtained with the EZNA Total RNA Kit (Omega) and quantified with a Nanodrop spectrophotometer. cDNAs were prepared with the SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen) in a 20 μL volume per reaction. GLI1, PTCH1, and control GAPDH primers were tested for efficiency, and products were checked for the correct size before being used in test samples. qPCR was done with Mi-Hot Taq Mix (Metabion). Reactions were performed in 10 μL by the addition of 1 μL of cDNA, 20× Evagreen (Biotium), and 0.5 μL of each primer (10 μM) to a CFX96 thermocycler (Bio-Rad) according to the following protocol: 95°C for 10 min and 40 cycles of 95°C for 10 s and 60°C for 30 s. Melting curve analysis was performed for each pair of primers between 65°C and 95°C with 0.5°C temperature increments every 5 s. Relative gene expression data were analyzed by the ΔΔCt method. Reactions were done in triplicates, and results were derived from at least three independent experiments normalized to GAPDH and presented as relative expression levels. Individual expression values were normalized to GAPDH. Primer sequences were as follows: GLI1-F, 5′-AGCCTTCAGCAATGCCAGTGAC-3′; GLI1-R, 5′-GTCAGGACCATGCACTGTCTTG-3′; PTCH1-F, 5′-CTCATATTTGCCTTCG-3′; PTCH1-R, 5′-TCTCCAATCTTCTGGCGAGT-3′; GAPDH-F, 5′-AGCCACATCGCTCAGACAC-3′; and GAPDH-R, 5′-GCCCAATACGACCAAATCC-3′.

CRISPR/Cas9 Genome Editing

We performed CRISPR/Cas9 targeting of the SALL1 locus to generate a HEK293FT cell line carrying a TBS-like allele. We used online resources (CRISPRdesign and CRISPOR) to search for high-scoring sites in proximity to the site mutated in the TBSp.Pro332Hisfs∗10 fibroblasts. We chose the highest-scoring sgRNA target to design our vectors. All constructs were confirmed by sequencing, and cloning details are available upon request. Transient transfection and puromycin selection were followed by single-cell cloning and screening. After CRISPR/Cas9-mediated cutting, the resulting repair gave rise to the single-base insertion c.1003dup in SALL1; this change is predicted to give rise to the following protein: SALL1p.Ser335Lysfs∗20. This mutation was confirmed to be heterozygous by Sanger sequencing of a pooled mutant and WT amplicon, as well as individual sequencing of TOPO-cloned amplicons (both mutant and WT were detected).

Using the same online resources, we chose six of the highest-scoring off-target sites for additional analysis (mm2_exon_SALL1P1_chrX_49432372, mm4_exon_NACA_chr12_57110706; mm4_intergenic_CDCA7L|RAPGEF5_chr7_22092853; mm4_intergenic_RNU6-996P|AL162389.1_chr9_110472444; mm4_exon_LEMD2_chr6_33744586; and mm4_exon_GPRIN2_chr10_46999700). Using genomic DNA from our targeted clone as a template, we performed PCR and Sanger sequencing. In all cases, no mutations were found.

SALL1 Silencing

A human SALL1 target sequence (5′-CTGCTATTTGTATTGTGCTTT-3′, based on validated Mission shRNA TRCN0000003958; Merck, Sigma-Aldrich) was cloned into the inducible shRNA vector Tet-pLKO-puro (Addgene 21915).33 Lentivirus was produced in HEK293FT cells and used for transducing and stably selecting HEK293FT cells with puromycin (1 μg/mL). SALL1 silencing was induced for 72 hr with doxycycline (1 μg/mL).

Lentiviral Transduction

Lentiviral expression constructs were packaged with psPAX2 and pVSVG (Addgene) in HEK293FT cells, and lentiviral supernatants were used for transducing Shh-LIGHT2 and hTERT-RPE1 cells. Stable-expressing populations were selected with puromycin (1 μg/mL). For primary fibroblasts, lentiviral supernatants were concentrated 100-fold before use (Lenti-X concentrator, Clontech).

Luciferase Assays

Firefly luciferase expression was measured with the Dual-Luciferase reporter system (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For each construct, we divided luciferase activity upon purmorphamine treatment by the activity of cells before purmorphamine induction to obtain the fold-change value. Luminescence was measured, and data were normalized to the Renilla luciferase readout. Experiments were performed with both biological and technical replicates (n = 8).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad 6.0 software. Data were analyzed by the Shapiro-Wilk normality test and Levene’s test of variance. We used two-tailed unpaired Student’s t tests or Mann-Whitney U tests for comparing two groups and one-way ANOVA or the Kruskall-Wallis test for more than two groups. Significance was considered when p < 0.05.

Results

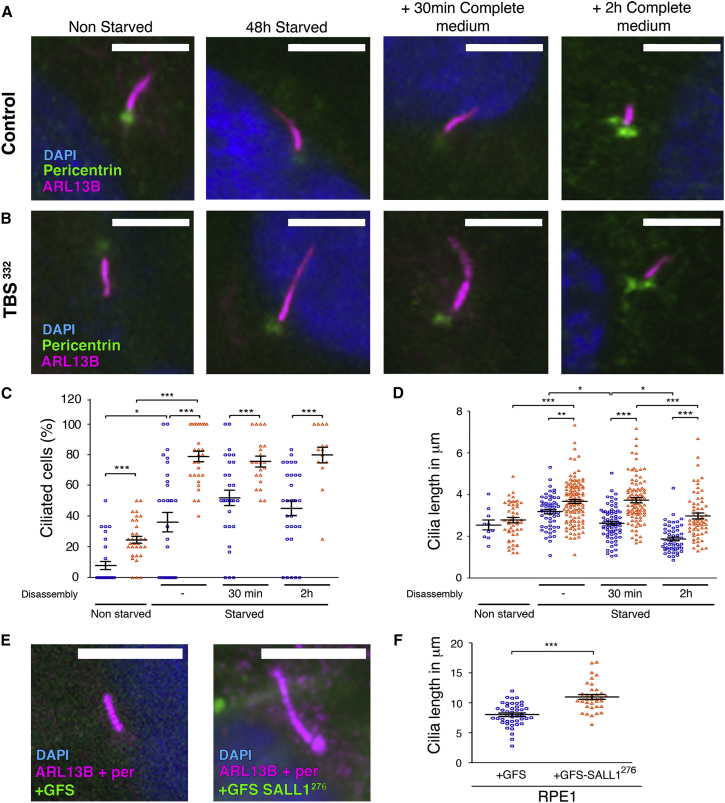

TBS-Derived Cells Show Increased Cilia Frequency and Length

On the basis of the phenotypic characteristics found in TBS individuals, we hypothesized that the formation of primary cilia might be altered in TBS cells. Therefore, we checked cilia assembly and disassembly in fibroblasts derived from both control (HFFs) and TBS (TBSp.Pro332Hisfs∗10) individuals (see Material and Methods).3, 8 We induced the assembly of primary cilia by starving cells at high confluence for 48 hr, whereas we induced cilia disassembly by adding complete media to ciliated cells that had previously been subjected to serum starvation. We quantified the frequency of ciliation and the length of primary cilia at all mentioned time points. TBS fibroblasts formed primary cilia at a significantly higher frequency when the cells were not subjected to starvation (Figures 1A–1C). 7.9% of the control cells (versus 24.7% of the TBS cells) exhibited a primary cilium in cycling conditions (Figure 1C). TBS cells were also significantly more ciliated than control fibroblasts upon 48 hr of starvation. In those conditions, 36.1% of the control cells (versus 78.8% of the TBS fibroblasts) displayed a primary cilium. In addition, TBS cells were significantly more ciliated 30 min and 2 hr after serum induction (Figure 1C). Whereas 100% of the control cells had completely dismantled their cilia 24 hr after cilia disassembly was induced, 12% of the TBS fibroblasts were still ciliated (data not shown). Furthermore, primary cilia were significantly longer in TBS cells upon 48 hr of starvation than in control cells (average 3.2 μm in control versus 3.7 μm in TBS cells) (Figure 1D). Cilia were significantly longer in TBS than in control cells at all the studied time points during cilia disassembly (30 min with complete medium: average 2.6 μm in control versus 3.7 μm in TBS cells; 2 hr with complete medium: 1.9 μm in control versus 3 μm in TBS cells). The observed increase in cilia frequency after the addition of complete medium in control cells is consistent with a reported reciliation wave during the first hours of cilia disassembly.34 These results show that TBS cells have longer and more abundant primary cilia than control cells in all tested conditions.

Figure 1.

TBSp.Pro332Hisfs∗10 Cells Show Aberrant Cilia Frequency and Length

(A and B) Micrographs of control HFFs (A) or TBSp.Pro332Hisfs∗10 cells (TBS332) (B) analyzed during cilia assembly and disassembly. Cilia were visualized by ARL13B (purple), basal bodies were visualized by pericentrin (green), and nuclei were visualized by DAPI (blue).

(C and D) Graphical representation of cilia frequency (C) and cilia length (D) measured in control HFFs (blue circles; n = 58 cilia) or TBS332 cells (orange triangles; n = 116 cilia) from three independent experiments. Cells that underwent 48 hr of starvation were compared with non-starved cells. After starvation, cells were supplied with serum for 30 min or 2 hr (n = 21–30 micrographs for all cases).

(E) Micrographs of RPE1 cells infected with lentivirus expressing GFS alone (left) or GFS-SALL1c.826C>T (GFS-SALL1276; right) and labeled with ARL13B (purple) and DAPI (blue).

(F) Graphical representation of cilia length measured in control (blue circles; n = 43 cilia) or GFS-SALL1276 (orange triangles; n = 36 cilia) RPE1 cells infected as in (E).

Graphs represent mean and SEM of three independent experiments. p values were calculated with a two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test: ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001. Scale bars, 5 μm.

As mentioned previously, it has been reported that the presence of truncated SALL1 is sufficient to cause a TBS-like phenotype in a mouse model.12 To generate a mutated form for exogenous expression, we chose the mutation SALL1c.826C>T because it has been reported in several individuals with TBS3 and is thus the most common allele in this rare syndrome. Confluent hTERT-RPE1 cells stably transduced with lentiviral GFS-SALL1c.826C>T displayed longer cilia (11 μm on average) than those stable for GFS alone (8 μm on average) (Figures 1E and 1F), further confirming that the presence of a truncated form of SALL1 is sufficient to promote longer cilia. Together, these results suggest that truncated SALL1 can affect cilia frequency, as well as the dynamics of cilia assembly and disassembly.

Truncated SALL1 Recruits SALL1FL to the Cytoplasm in TBS-Derived Fibroblasts

In humans, a truncated SALL1 was observed in B cells derived from a TBS individual,12 but its presence in fibroblasts has not been reported. It was previously shown that mRNA from the truncated allele was expressed in TBSc.995delC fibroblasts,8 so we checked for the presence of truncated SALL1 by western blot. For that, we took advantage of distinct antibodies recognizing different epitopes of SALL1 (see Material and Methods; Figures S1A, S1B, and S2), which allowed us to distinguish SALL1FL from the truncated forms. Using an antibody directed against the N-terminal portion of SALL1, we identified a truncated protein of about 62 kDa in TBSp.Pro332Hisfs∗10 cells but not in control fibroblasts (Figure S1C). Furthermore, SALL1FL was less abundant in TBS cells than in control HFFs. As previously reported, the observed size of SALL1 by western blot was higher than expected.12

SALL1FL proteins are normally enriched in the nucleus, whereas truncated forms have been observed in both the nucleus and cytoplasm.7, 35 These studies used overexpression of truncated murine or chicken forms of Sall1, which induced a mislocalization of SALL1FL into the cytoplasm, most likely as a result of the interaction of the different SALL1 proteins through their glutamine-rich domains.7, 35 We therefore analyzed whether the reported change in localization of endogenous SALL1 was also occurring in human TBSp.Pro332Hisfs∗10 cells. By immunofluorescence, TBSp.Pro332Hisfs∗10 fibroblasts presented abnormal cytoplasmic staining of SALL1FL (Figures S3A and S3B). We quantified the fluorescence intensity of SALL1FL in the nuclei and cytoplasm in both control HFFs and TBSp.Pro332Hisfs∗10 human fibroblasts. SALL1FL intensity was significantly lower in the nuclei but significantly higher in the cytoplasm of TBS fibroblasts, leading to a decrease in the nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio (Figure S3C). No significant differences in nuclear or cytoplasmic size were found between control and TBS fibroblasts, indicating that the changes in intensity were not due to differences in size (Figure S3D).

To check whether the presence of the truncated protein in human cells is sufficient to produce the localization change of SALL1FL, we transiently transfected U2OS cells with SALL1FL-2xHA, with SALL1c.826C>T-YFP, or with a combination of both. As expected, SALL1p.Arg276∗-YFP localization was diffuse in the nucleus and cytoplasm (Figure S1D), whereas SALL1FL localization was limited to the nuclei in a typical pattern of subnuclear spots (Figure S1E). However, in the presence of SALL1p.Arg276∗, SALL1FL changed its localization and colocalized with SALL1p.Arg276∗ (Figure S1F).

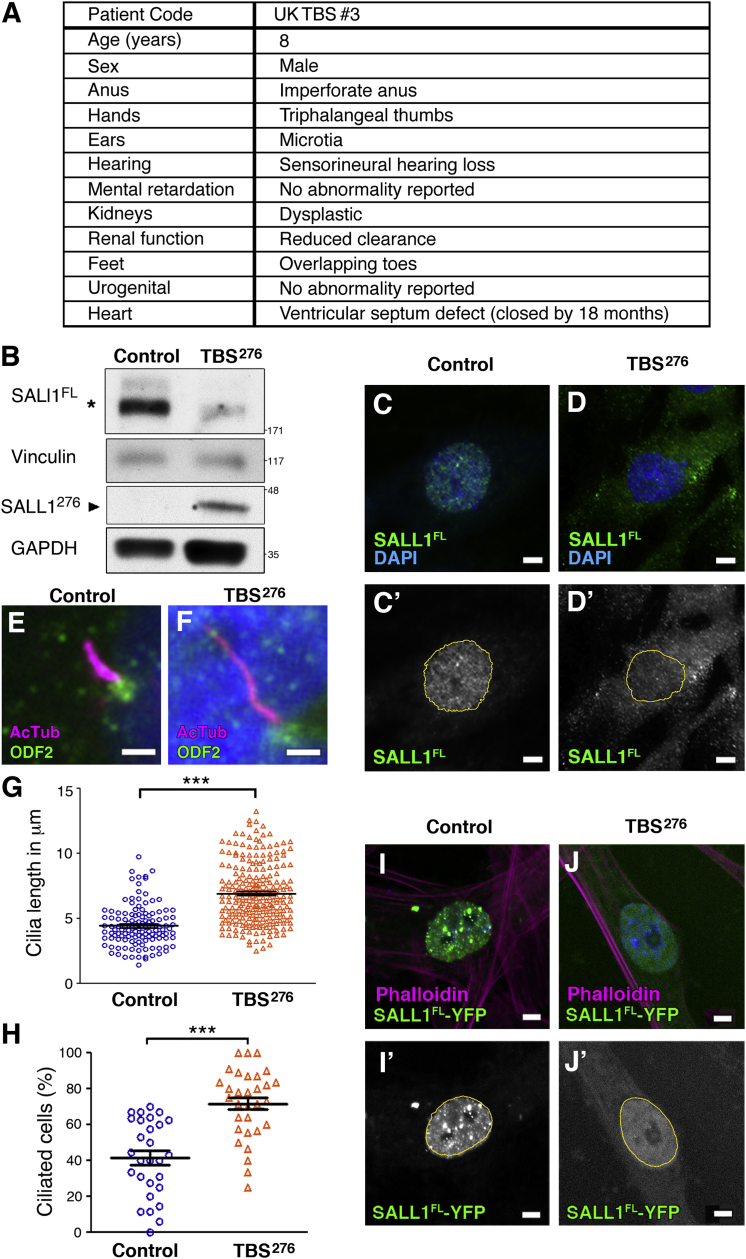

New TBS-Derived Cell Line Exhibits Cilia Alterations

To further verify these results, we analyzed the amount of SALL1 and cilia formation in fibroblasts derived from an additional individual referred to as TBSp.Arg276∗ (Figure 2A). Of note, this is the same truncation that was used in our exogenous expression constructs (i.e., SALL1c.826C>T). When analyzing TBSp.Arg276∗ cells, we observed less SALL1FL than in control ESCTRL#2 cells and the presence of a new band of about 42 kDa, consistent with a truncated SALL1 (Figure 2B and Figure S2). Interestingly, localization of SALL1FL was also altered in human TBSp.Arg276∗ cells (Figures 2C and 2D). Furthermore, compared with control ESCRTL#2 cells, TBSp.Arg276∗ cells displayed longer and more abundant cilia in confluent starved conditions, similar to what was observed in TBSp.Pro332Hisfs∗10 cells (Figures 2E–2H). To check whether the presence of the truncated protein in primary human cells is sufficient to produce the localization change of SALL1FL, we transiently transfected control and TBSp.Pro332Hisfs∗10 cells with SALL1FL-YFP. SALL1FL localization was limited to the nuclei in control fibroblasts (Figure 2I), whereas its localization was diffuse in the nucleus and cytoplasm in TBSp.Arg276∗ cells (Figure 2J). Thus, truncated SALL1 is present in TBS-derived cells and leads to altered SALL1FL localization, most likely through recruitment to the cytoplasm. As a result, the truncated SALL1, SALL1FL, or both can potentially interact and interfere with other proteins.

Figure 2.

Fibroblasts Derived from an Additional TBS Individual Exhibit Cilia Anomalies

(A) Clinical findings in individual TBSp.Arg276∗ (TBS276).

(B) Western blot analysis of lysates from control ESCTRL#2 and TBS276. Samples were run in duplicate on the same gel and probed against SALL1FL (asterisk, R&D antibody) or against SALL1276 (black arrowhead, N-terminal specific antibody6) TBS276 cells encoded with a ∼48 kDa truncated protein that positively reacts against SALL1 antibody. Vinculin and GAPDH were used as loading controls. Molecular-weight markers are shown to the right.

(C and D) Confocal micrographs showing endogenous SALL1FL localization in control ESCTRL#2 (C) or TBS276 (D) fibroblasts detected by FL-specific antibody (R&D). DAPI was used to label the nuclei (blue), and black and white images show the single green channel. Scale bars, 5 μm.

(E and F) Immunofluorescence micrographs showing cilia marked with acetylated tubulin (purple), basal bodies marked with ODF2 (green), and nuclei marked with DAPI (blue) in control ESCTRL#2 and TBS276 fibroblasts. Pictures were taken with a Zeiss Axioimager D1 fluorescence microscope with a 63× objective. Scale bars, 2.5 μm.

(G and H) Graphical representation of cilia length measurements (G; n = 123 and 235 cilia for control ESCTRL#2 and TBS276 fibroblasts, respectively) and cilia frequency (H; n = 28 and 31 micrographs for control ESCTRL#2 and TBS276 fibroblasts, respectively) of micrographs as shown in (E) and (F). Three independent experiments were pooled together. The graphs represent the mean and SEM. The p values were calculated with a two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test: ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

(I and J) Confocal micrographs showing SALL1FL-YFP localization in control ESCTRL#2 and TBS276 fibroblasts. Actin is labeled by phalloidin (purple), and nuclei are labeled by DAPI (blue). Black and white images show the single green channel. Scale bars, 5 μm.

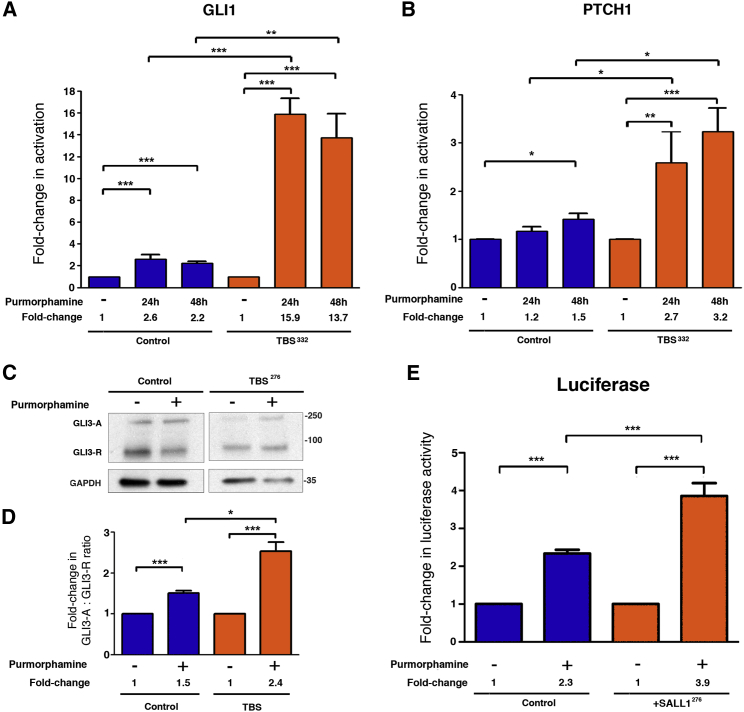

TBS-Derived Cells Exhibit Aberrant Sonic Hedgehog Signaling

It is well established that SHH signal transduction is dependent on the presence of functional primary cilia in mammals.18, 19 Therefore, we examined whether SHH signaling is compromised in TBSp.Pro332Hisfs∗10 cells. We starved cells for 24 hr and incubated in the presence or absence of purmorphamine (a SMO agonist) for 24 or 48 hr to activate the SHH pathway. mRNA expression of two SHH target genes (GLI1 and PTCH1) was quantified by qRT-PCR (Figures 3A and 3B). We found that, after induction by purmorphamine for 24 or 48 hr, the relative increases in expression (fold change) of GLI1 and PTCH1 were higher in TBS cells than in control HFFs. To further study the role of SALL1 truncations in SHH signaling, we analyzed GLI3 processing by western blot analysis using total lysates extracted from control and TBS fibroblasts (Figure 3C). We found that the increase in the GLI3-A/GLI3-R ratio (activator/represor) upon purmorphamine treatment was significantly higher in TBS cells than in control fibroblasts (Figures 3C and 3D). We also examined the effects of truncated SALL1 on SHH signaling by using Shh-LIGHT2 cells.25 These are NIH 3T3 mouse fibroblasts that carry an incorporated SHH reporter (firefly luciferase under the control of the Gli3-responsive promoter). We observed aberrations in SHH signaling between Shh-LIGHT2 cells stably expressing GFS-SALL1c.826C>T and controls (Figure 3E). Like TBS-derived cells, Shh-LIGHT2 cells overexpressing GFS-SALL1c.826C>T were more sensitive to SHH induction than control cells (2.3-fold induction in control cells versus 3.8-fold induction in cells expressing GFS-SALL1c.826C>T). Defects in PTCH1 and GLI1 expression (endogenous or via reporter assay) and impaired GLI3 processing confirm that truncated SALL1 proteins found in TBS might cause not only defects in ciliogenesis but also defects in SHH signaling.

Figure 3.

TBSp.Pro332Hisfs∗10 Fibroblasts Show Aberrant SHH Signaling

(A and B) Graphical representation of the fold change of activation based on the relative expression of GLI1 (A) and PTCH1 (B) obtained by qPCR from control HFFs (n = 4; blue bars) or TBSp.Pro332Hisfs∗10 fibroblasts (TBS332) (n = 4; orange bars) either treated or not (−) with purmorphamine for the indicated times. Numerical values for the fold change are indicated.

(C) Western blot analysis of lysates from control ESCTRL#2 and TBSp.Arg276∗ (TBS276). Samples were probed against GLI3 (A, activator; R, repressor), and GAPDH was used as a loading control. Molecular-weight markers are shown to the right.

(D) Graphical representation is shown for the fold change of the GLI3-A:GLI3-R ratios obtained in (C) for control and TBS fibroblasts. Data from at least three independent experiments using ESCTRL#2 (control; n = 3; blue bars) and TBS (TBS276∗ and TBS332; pooled; n = 5; orange bars) are shown.

(E) Graphical representation of the fold change in luciferase activation when Shh-LIGHT2 control cells (n = 8; blue bars) or cells expressing the mutated form GFS-SALL1c.826C>T (SALL1276; n = 8; orange bars) were either treated (+) or not (−) with purmorphamine.

All graphs represent the mean and SEM. p values were calculated with a two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test: ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

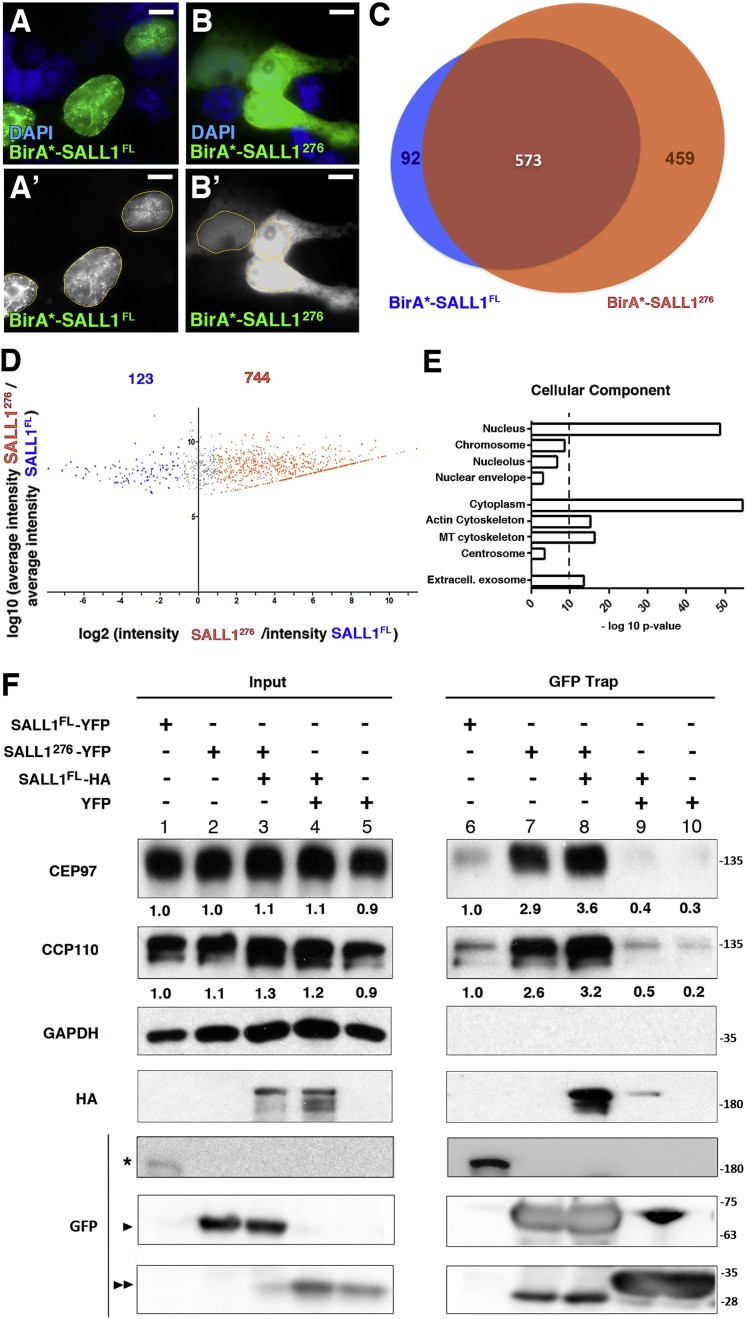

Proximity Proteomics of SALL1 Identifies Interactions with Cilia Regulators

Given that truncated SALL1 proteins and SALL1FL display differential subcellular localization, we reasoned that TBS might be a consequence of aberrant cytoplasmic interactions by the truncated SALL1. In order to identify those possible interactors, we applied proximity proteomics to either SALL1p.Arg276∗ or SALL1FL. The BioID method28 relies on a mutant BirA enzyme (BirA∗) that has a relaxed specificity and is able to biotinylate any free lysine ε-amino group present in a protein within a radius between 10 and 20 nm.36, 37 When fused to SALL1p.Arg276∗ or SALL1FL, BirA∗ can biotinylate proximal proteins that either interact directly with them or are closely associated in protein complexes.

Myc-BirA∗-tagged SALL1c.826C>T or SALL1FL plasmids were transfected in HEK293FT cells. Staining of transfected cells for visualizing biotinylated proteins revealed that, as expected, BirA∗-SALL1p.Arg276∗ was localized diffusely throughout the nucleus and cytoplasm, whereas BirA∗-SALL1FL was localized primarily in the nucleus and enriched in subnuclear domains (Figures 4A and 4B). Total lysates from Myc-BirA∗-SALL1c.826C>T- or SALL1FL-transiently transfected cells were subjected to NeutrAvidin pull-down, and isolated proteins were analyzed by LC-MS/MS. In addition to almost all known interactors of SALL1, such as NuRD complex components (HDAC1, HDAC2, RbAp46, MTA1, MTA2, MBD3, CHD4, and CHD3),38 candidates with exclusive or enriched proximity to SALL1p.Arg276∗ or SALL1FL were identified (Table S1). A total of 1,032 or 665 proteins were found in at least two out of three experiments done with SALL1p.Arg276∗ or SALL1FL, respectively (Figure 4C). However, out of those proteins, 744 in the SALL1p.Arg276∗ subproteome and 123 in the SALL1FL subproteome were significantly enriched at least 2-fold with respect to the other subproteome according to label-free protein quantitation (Figure 4D and Table S1).

Figure 4.

CCP110 and CEP97 Interact with Truncated SALL1

(A and B) Confocal micrographs showing transient expression of transfected BirA∗-SALL1FL (A) or BirA∗-SALL1c.826C>T (BirA∗-SALL1276) (B) detected by fluorescence streptavidin. Nuclei are marked by DAPI in blue. Single green channels are shown in black and white (A′ and B′). Scale bars, 5 μm.

(C) Venn diagram showing the distribution of the identified candidates by MS analysis. 665 and 1,032 proteins were found in close proximity of SALL1FL and SALL1p.Arg276∗ (SALL1276), respectively, in at least two independent experiments.

(D) Volcano plot representing the distribution of the candidates identified by proximity proteomics in at least two out of three independent experiments. Proteins with at least a 2-fold change in intensity with respect to the WT proteome (log2 ≥ 1) were considered SALL1276-associated candidates (orange dots). Proteins with less than a 2-fold change in intensity with respect to the WT proteome (log2 ≤ 1) were considered SALL1FL associated candidates (blue dots).

(E) Graphical representation of the −log10 of the p value for each of the represented cellular component GO terms. MT, microtubule; Extracell, extracellular.

(F) Western blot of inputs or GFP-Trap pull-downs performed in HEK293FT cells transfected with SALL1FL-YFP (lanes 1 and 6), SALL1c.826C>T-YFP (SALl1276-YFP; lanes 2 and 7), SALL1276-YFP together with SALL1FL-2xHA (SALL1FL-HA; lanes 3 and 8), SALL1FL-HA together with YFP alone (lanes 4 and 9), or YFP alone (lanes 5 and 10). Endogenous CCP110 and CEP97 were detected with specific antibodies. GAPDH was used as a loading control. Numbers under the CCP110 and CEP97 panels are the result of dividing the band intensities of each lane by that of lane 1 for the inputs or by that of lane 6 for the pull-downs. One asterisk indicates SALL1FL-YFP, one black arrowhead indicates SALL1276-YFP, and two black arrowheads indicate YFP alone. Molecular-weight markers are shown to the right.

With the purpose of obtaining a functional overview of the main pathways associated with SALL1p.Arg276∗, we performed a comparative GO analysis to compare the “cellular component,” “molecular function,” and “biological process” domains (Figure 4E, Figures S4A and S4B, and Table S1). In the cellular component domain, a shift toward “cytoplasm,” “actin,” and “microtubule cytoskeleton” was observed in the SALL1p.Arg276∗ proteome (Figure 4E and Table S1). Intriguingly, the “centrosome” GO term was found exclusively in the SALL1p.Arg276∗ proteome. Interestingly, among genes included in this category, we found CCP110 and CEP97.39 The role described for these proteins in cilia formation is compatible with the phenotype observed in TBS fibroblasts, so we selected them for further study. We confirmed these proteins as proximal interactors by independent BioID experiments analyzed by western blot by using CCP110 and CEP97 antibodies. Both proteins associated preferentially with BirA∗-SALL1p.Arg276∗ (Figures S4C, S4D, and S3). With respect to molecular function, SALL1p.Arg276∗ showed enrichment in cytoplasmic proteins (“actin,” “microtubule binding,” “ATPase activity,” or “helicase activity” terms; Figure S4A and Table S1). In the category of biological process, the SALL1p.Arg276∗ subproteome showed enrichment in the categories “cell cycle,” “cytoskeleton organization,” and “cell response to stress” (Figure S4B and Table S1).

CCP110 and CEP97 Interact with SALL1

Most cases of TBS exhibit a monoallelic truncation of SALL1, i.e., the presence of both truncated and FL forms of SALL1. These proteins can homo- and heterodimerize, leading to aberrant complexes. To characterize the interaction between SALL1 and both CCP110 and CEP97, we performed pull-downs with tagged SALL1FL-YFP, SALL1p.Arg276∗-YFP, or a combination of both in HEK293FT cells. Our results showed that both endogenous CCP110 and CEP97 were able to bind to both SALL1FL and SALL1p.Arg276∗ and bound preferentially to the truncated SALL1p.Arg276∗, confirming our MS results (Figure 4F and Figure S2, lanes 6 and 7). The binding to SALL1p.Arg276∗ persisted in the presence of overexpressed SALL1FL (Figure 4F and Figure S2, lane 8), indicating that the heterodimerization of the truncated and FL forms does not inhibit the interaction with CCP110 and CEP97. Note that SALL1276-YFP can interact with SALL1FL-HA (HA panel, lane 8), as previously suggested.35 We further demonstrated the specificity of the interaction between SALL1 and both CCP110 and CEP97 by performing the reciprocal experiment (Figures S4E, S4F, and S2). These results support the notion that the truncated form of SALL1, either by itself or in complex with the FL form, can bind and perhaps sequester or inhibit the important cilia regulatory factors CCP110 and CEP97.

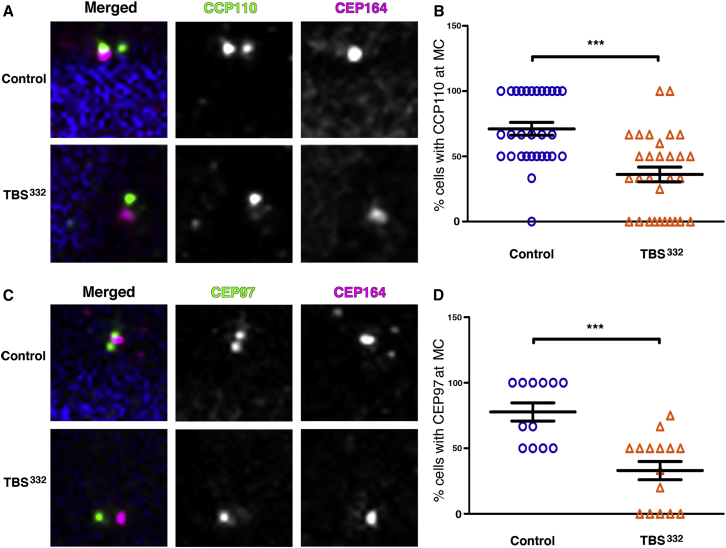

CCP110 and CEP97 Dynamics Are Altered in TBS Fibroblasts

One key event in ciliogenesis is the depletion of CCP110 and CEP97 from the distal end of the MC, promoting the ciliary activating program in somatic cells.39, 40, 41, 42, 43 On the basis of the results shown above, we hypothesized that CCP110 and CEP97 might suffer displacements from the MC. In order to check this hypothesis, we analyzed their centrosomal localization in primary TBSp.Pro332Hisfs∗10 fibroblasts by immunofluorescence. CCP110 was present at the MC in a higher proportion of control cells (74%) than TBSp.Pro332Hisfs∗10 cells (36%) (Figures 5A and 5B). Notably, 10% of the TBS cells displayed multiple foci or more diffuse labeling of CCP110 around the centrioles, suggesting an alteration of CCP110 dynamics (Figures S5A and S5B). Furthermore, CEP97 was present at the MC in 78% of the control cells but in 33% of the TBSp.Pro332Hisfs∗10 cells (Figures 5C and 5D). Therefore, the disruption in the localization of CCP110 and CEP97 by the truncated SALL1 or by the complex between SALL1FL and SALL1 truncations is a potential mechanism by which CCP110 and CEP97 might be depleted from the MC and thus lead to a higher frequency of ciliogenesis in TBS cells.

Figure 5.

TBSp.Pro332Hisfs∗10 Cells Show Changes in the Localization of CCP110 and CEP97

(A and C) Immunofluorescence micrographs of cycling human-derived fibroblasts stained with antibodies against endogenous CCP110 (A) or CEP97 (C) (green), CEP164 to label the mother centriole (MC; purple), and DAPI to label the nuclei (blue). Black and white images show the single green and purple channels. Note the different distribution of CCP110 and CEP97 to the MC between TBSp.Pro332Hisfs∗10 fibroblasts (TBS332) and control HFFs.

(B and D) Graphical representation of the percentage of cells showing the presence of CCP110 or CEP97 at the MC per micrograph corresponding to the experiments in (A) or (C), respectively; n = 30 micrographs. Three independent experiments were pooled together. Pictures were taken with a Zeiss Axioimager D1 fluorescence microscope with a 63× objective. All graphs represent the mean and SEM. Scale bars, 1 μm.

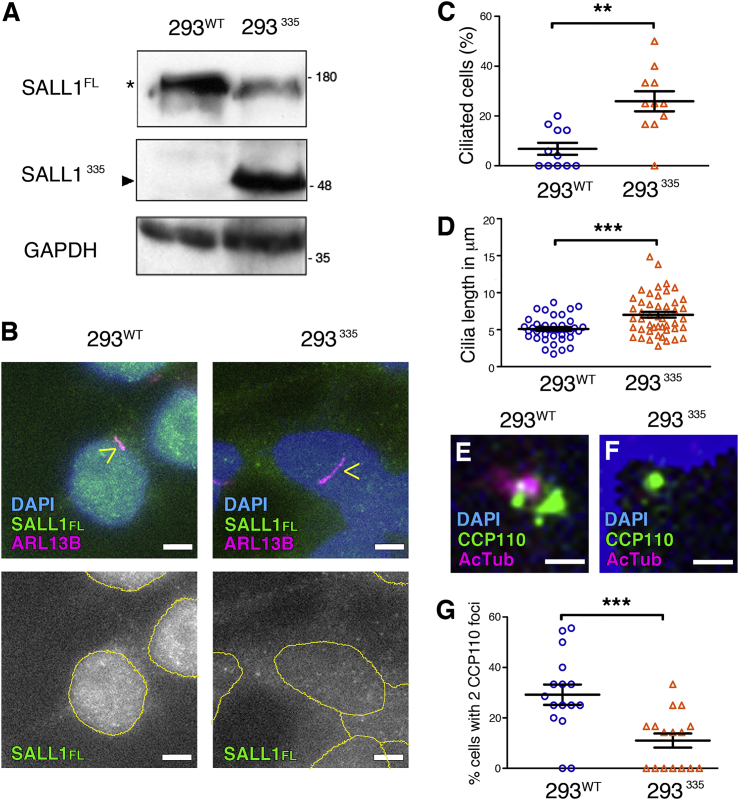

TBS-Mimicking Cell Line Exhibits Aberrant Ciliogenesis

Our BioID experiments were done in HEK293FT cells, which express SALL1 and are capable of forming primary cilia. Therefore, we attempted to generate a TBS-like mutation in HEK293FT cells to assess the cilia phenotype. In addition, this would allow us to confirm that the observed differences in ciliogenesis are not dependent on the genetic background of the cells, given that the TBS-like model cell line could be compared with the parental cells.

We used the CRISPR/Cas9 method to target the SALL1 locus in the “hotspot” region to approximate the mutation seen in TBSp.Pro332Hisfs∗10 fibroblasts. We isolated and characterized a clone that is heterozygous for a SALL1 mutation with a sequence-verified single-base insertion that leads to a frameshift and a truncated protein (SALL1c.1003dup; SALL1p.Ser335Lysfs∗20; hereinafter referred to as 293335).

In the 293335 cells, we observed dramatically less SALL1FL than in unmodified cells (293WT) and the presence of a new ∼48 kDa band, corresponding to truncated SALL1, that showed reactivity with SALL1 antibody, (Figure 6A and Figure S2). Interestingly, localization of SALL1FL changed in 293335 cells. Whereas SALL1FL was nuclear in 293WT cells, it was diffusely localized throughout the nucleus and the cytoplasm in 293335 cells (Figure 6B). Upon starvation and in confluent conditions, cilia were significantly more abundant in 293335 cells (average 26%) than in 293WT cells (average 7%) (Figures 6B and 6C). Furthermore, 293335 cells displayed longer cilia (7.0 μm on average) than did 293WT cells (5.1 μm on average) (Figures 6B and 6D). In addition, changes in cilia length were accompanied by the absence or reduction of CCP110 foci at the MC in most of the 293335 cells (Figures 6E–6G). Together, our results indicate that, compared with a control of the same genetic background, truncated SALL1 is sufficient to promote changes in cilia length and CCP110 localization.

Figure 6.

Truncated SALL1 Leads to a TBS-like Cilia Phenotype in Genetically Modified Cells

(A) Western blot analysis of lysates from WT HEK293FT cells (293WT) or CRISPR/Cas9 cells (293335 cells). The latter were modified to mimic a TBS mutation in SALL1 (SALL1c.1003dup). A truncated protein of about 48 kDa was identified in 293335 cells by SALL1 antibody (SALL1p.Ser335Lysfs∗20; arrowhead). The asterisk indicates SALL1FL. GAPDH was used as a loading control. Molecular-weight markers are shown to the right.

(B) Micrographs of immunofluorescence using a specific antibody (green) show the subcellular distribution of SALL1FL in control or mutated cells. ARL13B marks the primary cilium (purple and yellow arrowheads), and DAPI marks the nuclei. Yellow circles indicate the nuclei, and black and white images show the single green channel. Scale bars, 5 μm.

(C and D) Graphical representation of cilia frequency (C) and cilia length measurements (D) of micrographs shown in (B) (cilia frequency: n = 11 micrographs; cilia length: n = 38 cilia in 293WT cells and n = 48 cilia in 293335 cells). Three independent experiments were pooled together. The graphs represent the mean and SEM. The p values were calculated with a two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test: ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

(E and F) Immunofluorescence micrographs of 293WT or 293335 cells showing centrosomes (purple), CCP110 foci (green), and nuclei (DAPI in blue). Scale bars, 1 μm. Pictures were taken with a Zeiss Axioimager D1 fluorescence microscope with a 63× objective.

(G) Graphical representation of the percentage of cells showing CCP110 in two foci per micrograph in 293WT or 293335 cells, corresponding to the experiments in (E) or (F), respectively.

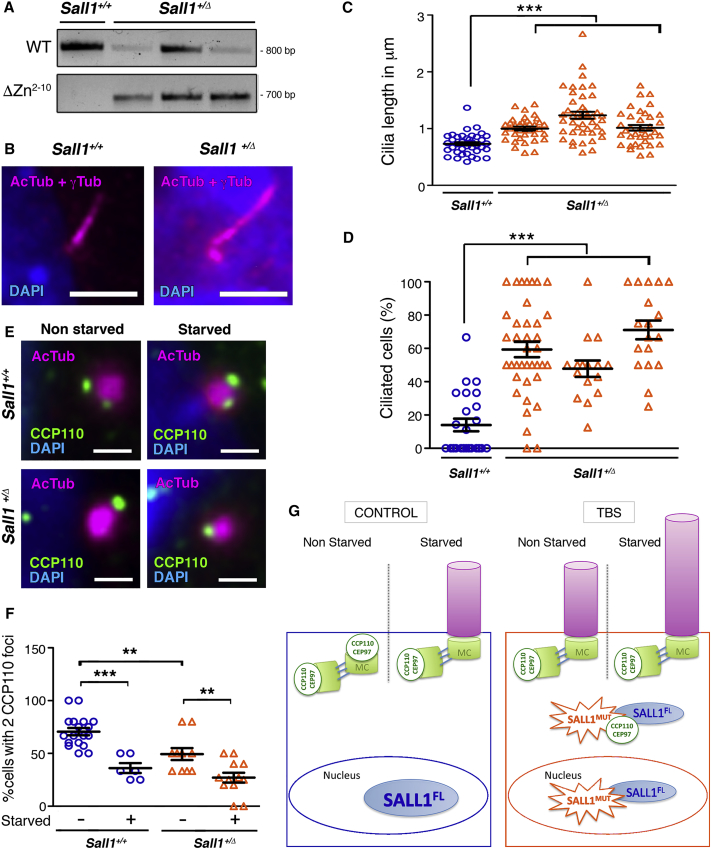

Cells Derived from Sall1-ΔZn2–10 Mouse Embryos Exhibit Aberrant Ciliogenesis

To further confirm the results shown above, we examined cells from a TBS animal model that had been previously characterized. Sall1-ΔZn2–10 mice mimic a hotspot mutation shown to cause TBS, and they produce a truncated protein lacking most of the zinc finger motifs.11 We analyzed cilia formation in MEFs. After confirming the genotype by PCR (Figure 7A), we analyzed ciliogenesis in WT (Sall1+/+) and heterozygous (Sall1+/Δ) MEFs. In agreement with our previous results, Sall1+/Δ MEFs displayed longer (pooled average 1 μm) and more abundant (pooled average 59%) cilia than Sall1+/+ MEFs (average 0.7 μm and 14%, respectively) both in starved conditions (Figures 7B–7D). In addition, the absence or reduction of CCP110 foci at the MC in most of the Sall1+/Δ cells was also observed in the MEFs (Figures 7E and 7F). In summary, we have shown that MEFs derived from a mouse TBS model reproduced the ciliary phenotype found in human TBS fibroblasts.

Figure 7.

Cells Derived from Sall1+/Δ Mouse Embryos Exhibit Cilia Defects

(A) PCR genotyping of MEFs derived from WT homozygous (Sall1+/+) or Sall1-ΔZn2–10 heterozygous (Sall1+/Δ) embryos.

(B) Micrographs of Sall1+/+ and Sall1+/Δ MEFs analyzed during cilia assembly. Cilia were visualized by acetylated alpha-tubulin and gamma-tubulin (AcTub and γTub, respectively; purple), and nuclei were visualized by DAPI. Scale bar, 1 μm.

(C and D) Graphical representation of cilia length (C) and cilia frequency (D) measured in Sall1+/+ (n = 38 cilia and 24 micrographs for cilia length and frequency, respectively; blue circles) and Sall1+/Δ MEFs in (B) (n = 37–45 cilia and n = 16–38 micrographs for cilia length and frequency, respectively; orange triangles).

(E) Immunofluorescence micrographs of Sall1+/+ and Sall1+/Δ MEFs showing the centrosomes (AcTub, purple), CCP110 foci (green), and nuclei (DAPI). Scale bars, 0.5 μm. Cells that underwent 48 hr of starvation were compared with non-starved cells. Pictures were taken with a Deltavision fluorescence microscope (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) with a 60× objective.

(F) Graphical representation of the percentage of cells showing CCP110 in two foci in Sall1+/+ and Sall1+/Δ MEFs in (E) (n > 10). The graphs represent the mean and SEM. p values were calculated by one-way ANOVA: ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

(G) The presence of a truncated SALL1 underlies cilia malformations in TBS. In control cells (left), SALL1FL is mainly nuclear, and CCP110 and CEP97 localize in the mother and daughter centrioles, inhibiting cilia formation. Upon starvation, CCP110 and CEP97 are depleted from the MC, which will allow the formation of the primary cilia. By contrast, in TBS cells (right) a truncated form of SALL1, together with sequestered SALL1FL, localizes in the cytoplasm, where it interacts with centrosomal proteins such as CCP110 and CEP97, displacing them from the MC. As a result, the frequency of cilia formation increases, and cilia are longer than in control cells. Problems in cilia assembly are accompanied by altered SHH signaling in TBS cells.

Discussion

Phenotypes observed in TBS individuals fall within the spectrum of those observed in ciliopathies, leading us to speculate that cilia malfunction and/or malformation are contributing factors in the TBS-related limb, ear, anus, and kidney problems. Our work provides this mechanistic connection between truncated SALL1 and primary cilia, offering new clues about TBS etiology. In addition to its function as a transcription factor in the nucleus, SALL1 mutations, especially those found in the hotspot that generate mislocalized truncated proteins,3 might lead to aberrant cilia function. Three lines of evidence support our conclusions. First, TBS cells display significantly longer and more abundant cilia than control fibroblasts. Second, signaling through primary cilia is functionally defective in TBSp.Pro332Hisfs∗10 fibroblasts and in Shh-LIGHT2 cells that exogenously express the mutated form SALL1c.826C>T. Third, proteins necessary for the formation and function of primary cilia show altered dynamics in TBSp.Pro332Hisfs∗10 fibroblasts, the 293335 TBS model cell line, and Sall1+/Δ MEFs.

Aberrant Interactions of Truncated SALL1

The presence of truncated SALL1 in the cytoplasm and its capacity to form inappropriate protein interactions could contribute to TBS. This hypothesis relies on the presence of the truncated form, which we were able to detect in TBS-derived dermal fibroblasts and in a genome-edited kidney-derived model cell line (293335). In all these cases, the observed sizes of SALL1FL and its truncated forms were higher than their expected molecular weight, as shown by western blot. This has been previously observed12 and might be consistent with differential SALL1 binding to SDS detergent or with the presence of excessive proline residues that might cause structural rigidity and thereby decrease electrophoretic mobility. Alternatively, posttranslational modifications could also account for variations in the expected molecular weight.

By examining dermal fibroblasts, which display primary cilia and are competent for SHH signaling, we have shown that truncated SALL1 has multiple effects on cilia formation and function. We conclude that this could be due to dominant-negative binding and displacement of cilia-related factors by the truncated forms of SALL1, alone or in complex with SALL1FL. Notwithstanding, some aspects of the disease might result from the sequestration of SALL1FL to the cytoplasm, which might interfere with the transcriptional role of SALL1 in the nucleus, altering cilia through aberrant regulation of downstream genes. Other SALL proteins (SALL2, SALL3, and SALL4) might also heterodimerize with truncated SALL111 and thus contribute to the TBS etiology, as suggested by mouse studies that combine mutations in multiple Sall genes.44, 45 Interestingly, it has been reported that heterozygous deletions of SALL1 (i.e., haploinsufficiency) lead to a milder form of TBS,46 which might indicate that a certain dosage effect contributes to the TBS phenotype. How a reduction or loss of SALL1FL contributes to TBS etiology and cilia formation remains an intriguing subject for future research. SALL1 is also a transcriptional target of the SHH pathway,45, 47 raising the possibility that SALL1 is involved in feedback control, a common theme in SHH pathway regulation (e.g., PTCH1 and GLI1).

Primary Cilia Aberrations in TBS-Derived Cells

Compared with controls, TBS fibroblasts displayed longer, more frequent primary cilia, and those cilia took longer to be reabsorbed once serum was added to starved cells. Given that the dynamic balance between anterograde and retrograde transport determines cilia length,48 truncated SALL1 could affect proper ciliary length by directly or indirectly impairing ciliary transport dynamics.49 The presence of longer cilia in TBS-derived fibroblasts is consistent with other studies in which ciliary length was linked to phenotypes that overlap those observed in TBS individuals. For instance, cells derived from polydactylous Kif7 mutant mice displayed elongated cilia.50, 51, 52 Although not observed in all individuals, TBS can lead to polycystic kidneys. Consistently, kidney epithelial cells derived from a mouse model of nephronophthisis exhibit abnormally longer cilia. This model develops polycystic kidney disease.53, 54 Notably, a recent study concluded that the reduction of ciliary length attenuated cystic disease progression in these mice,55 suggesting that cilia-altering therapies could be beneficial to TBS individuals.

SHH Signaling Aberrations and TBS

Because TBS-derived cells had longer and more abundant primary cilia, we did not expect to observe defects in SHH signaling given its dependence on intact cilia. TBSp.Pro332Hisfs∗10-derived cells were hypersensitive to stimulation of the SHH pathway. Increases in SHH activity or its expression domain in the developing limb bud can cause preaxial polydactyly (a phenotype commonly seen in TBS individuals) in mice, chicks, and humans.56, 57, 58 SHH signaling defects might also underlie the pathogenesis of anorectal malformations in TBS individuals. For instance, it has been shown that Gli2−/− mice exhibit an imperforate anus, whereas Gli3−/− mice display less severe anal stenosis.59 In humans, some individuals with Pallister-Hall syndrome (MIM: 146510), which is caused by mutations in GLI3 (GLI-Kruppel family member 3 [MIM: 165240]), also exhibit anorectal malformations.60 Developmental pathways governing human outer-ear morphology are largely unexplored, but SHH signaling might be a contributing factor to TBS hearing problems given that SHH influences both proper cochlear and sensory epithelial development in mice and auditory function in humans.61

CCP110 and CEP97, Candidate Mediators of TBS Etiology

Our BioID experiments showed an enrichment of ciliary and/or centrosomal proteins among the potential interactors of truncated SALL1p.Arg276∗, which might underlie the observed ciliary defects. Among the SALL1p.Arg276∗-specific proximal interactors, approximately 6% of the proteins corresponded to verified ciliary genes previously identified by the SYSCILIA Consortium, and an additional 18% corresponded to their list of potential ciliary genes.62 In addition, 6.5% of the SALL1p.Arg276∗-specific list was present among the 384 centrosome-localized proteins identified by the Human Protein Atlas project according to subcellular localization.63 From among these candidates, we selected CCP110 and CEP97, which are important negative regulators of ciliogenesis.39, 49, 64, 65 The removal of these regulators is a key early event in ciliogenesis: depletion of CCP110 and CEP97 leads to the premature formation of aberrant cilia, whereas their overexpression blocks ciliogenesis, consistent with the increased frequency of primary cilia in TBS-derived cells. Although some studies demonstrated that removal of CCP110 was sufficient to induce ectopic cilia formation,39, 41 others reported that its depletion promoted abnormal elongation of non-docked centriolar microtubules.64, 66 A recent publication suggested that a context-dependent role of CCP110 in cilia formation is linked to its interactors in a particular subcellular environment.67 Importantly, consistent with altered CCP110 localization at the MC in TBSp.Pro332Hisfs∗10 cells, CCP110-KO mice exhibited preaxial polydactyly, heart malformations, and cleft palate among other problems. Understanding the exact contribution of CCP110 and its protein interaction network in the context of TBS, which could function in a tissue- or organ-dependent manner, would be of high relevance.

In conclusion, we propose that TBS is a potential ciliopathy-like disease with symptoms caused by truncated SALL1’s interference with the normal function of cilia and/or centrosomal-related proteins (Figure 7G). The ciliopathies are an expanding class of human genetic disorders, and our work provides a framework for understanding TBS with a focus on primary cilia. This does not rule out a disruption in the nuclear role of SALL1 or dominant interactions with other proteins in the SALL family. Different alleles might exhibit different strengths depending on the interactors. Genetic, environmental, or stochastic modifiers also might influence the phenotypic spectrum in TBS individuals (see GeneReviews in the Web Resources).11 Defining the degree to which primary cilia and other factors are implicated in the etiology of TBS could drive future therapeutic approaches.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the tissue donors and their families for their generosity. We thank M. Vivanco (CIC bioGUNE) for donating control tissue and C. Johnson and A. Magee for providing reagents. R.B. thanks the Spanish MINECO (BFU2014-52282-P and BFU2017-84653-P), the Severo Ochoa Excellence Accreditation (SEV-2016-0644), and Consolider Programs (BFU2014-57703-REDC). Support was provided by the Department of Industry, Tourism, and Trade of the Government of the Autonomous Community of the Basque Country (Etortek Research Programs) and by the Innovation Technology Department of the Bizkaia County. L.B.-B. thanks the Basque Government Department of Education for the fellowship PRE_2016_2_0226 and Boehringer Ingelheim for travel funding. J.A.R. is supported by funding from the Basque Government (IT634-13) and the University of the Basque Country UPV/EHU (UFI11/20). M.R. acknowledges support of the March of Dimes (6-FY13-127) and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (DK098563). We also thank the UPStream Consortium (ITN program PITN-GA-2011-290257, EU). Work at the Novo Nordisk Foundation Center for Protein Research is funded in part by a generous donation from the Novo Nordisk Foundation(NNF14CC0001).

Published: February 1, 2018

Footnotes

Supplemental Data include five figures and one table and can be found with this article online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2017.12.017.

Contributor Information

James D. Sutherland, Email: jsutherland@cicbiogune.es.

Rosa Barrio, Email: rbarrio@cicbiogune.es.

Web Resources

CRISPOR, http://crispor.tefor.net/

CRISPR Design, http://crispr.mit.edu

g:Profiler, http://www.biit.cs.ut.ee/gprofiler/

GeneReviews, Kohlhase, J. (2007). Townes-Brocks Syndrome, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1445/

MaxQuant, http://www.maxquant.org

Mutalyzer, http://mutalyzer.nl/

OMIM, http://www.omim.org/

Supplemental Data

References

- 1.Powell C.M., Michaelis R.C. Townes-Brocks syndrome. J. Med. Genet. 1999;36:89–93. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kohlhase J., Wischermann A., Reichenbach H., Froster U., Engel W. Mutations in the SALL1 putative transcription factor gene cause Townes-Brocks syndrome. Nat. Genet. 1998;18:81–83. doi: 10.1038/ng0198-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Botzenhart E.M., Bartalini G., Blair E., Brady A.F., Elmslie F., Chong K.L., Christy K., Torres-Martinez W., Danesino C., Deardorff M.A. Townes-Brocks syndrome: twenty novel SALL1 mutations in sporadic and familial cases and refinement of the SALL1 hot spot region. Hum. Mutat. 2007;28:204–205. doi: 10.1002/humu.9476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Celis J.F., Barrio R. Regulation and function of Spalt proteins during animal development. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2009;53:1385–1398. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.072408jd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Netzer C., Bohlander S.K., Hinzke M., Chen Y., Kohlhase J. Defining the heterochromatin localization and repression domains of SALL1. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2006;1762:386–391. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2005.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kiefer S.M., McDill B.W., Yang J., Rauchman M. Murine Sall1 represses transcription by recruiting a histone deacetylase complex. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:14869–14876. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200052200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sweetman D., Smith T., Farrell E.R., Chantry A., Munsterberg A. The conserved glutamine-rich region of chick csal1 and csal3 mediates protein interactions with other spalt family members. Implications for Townes-Brocks syndrome. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:6560–6566. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209066200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Furniss D., Critchley P., Giele H., Wilkie A.O. Nonsense-mediated decay and the molecular pathogenesis of mutations in SALL1 and GLI3. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2007;143A:3150–3160. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lauberth S.M., Bilyeu A.C., Firulli B.A., Kroll K.L., Rauchman M. A phosphomimetic mutation in the Sall1 repression motif disrupts recruitment of the nucleosome remodeling and deacetylase complex and repression of Gbx2. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:34858–34868. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703702200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nishinakamura R., Matsumoto Y., Nakao K., Nakamura K., Sato A., Copeland N.G., Gilbert D.J., Jenkins N.A., Scully S., Lacey D.L. Murine homolog of SALL1 is essential for ureteric bud invasion in kidney development. Development. 2001;128:3105–3115. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.16.3105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kiefer S.M., Ohlemiller K.K., Yang J., McDill B.W., Kohlhase J., Rauchman M. Expression of a truncated Sall1 transcriptional repressor is responsible for Townes-Brocks syndrome birth defects. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2003;12:2221–2227. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kiefer S.M., Robbins L., Barina A., Zhang Z., Rauchman M. SALL1 truncated protein expression in Townes-Brocks syndrome leads to ectopic expression of downstream genes. Hum. Mutat. 2008;29:1133–1140. doi: 10.1002/humu.20759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hildebrandt F., Benzing T., Katsanis N. Ciliopathies. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011;364:1533–1543. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1010172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wheatley D.N. Primary cilia in normal and pathological tissues. Pathobiology. 1995;63:222–238. doi: 10.1159/000163955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sorokin S. Centrioles and the formation of rudimentary cilia by fibroblasts and smooth muscle cells. J. Cell Biol. 1962;15:363–377. doi: 10.1083/jcb.15.2.363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gilula N.B., Satir P. The ciliary necklace. A ciliary membrane specialization. J. Cell Biol. 1972;53:494–509. doi: 10.1083/jcb.53.2.494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rezabkova L., Kraatz S.H., Akhmanova A., Steinmetz M.O., Kammerer R.A. Biophysical and Structural Characterization of the Centriolar Protein Cep104 Interaction Network. J. Biol. Chem. 2016;291:18496–18504. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.739771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huangfu D., Liu A., Rakeman A.S., Murcia N.S., Niswander L., Anderson K.V. Hedgehog signalling in the mouse requires intraflagellar transport proteins. Nature. 2003;426:83–87. doi: 10.1038/nature02061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yin Y., Bangs F., Paton I.R., Prescott A., James J., Davey M.G., Whitley P., Genikhovich G., Technau U., Burt D.W., Tickle C. The Talpid3 gene (KIAA0586) encodes a centrosomal protein that is essential for primary cilia formation. Development. 2009;136:655–664. doi: 10.1242/dev.028464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Behal R.H., Cole D.G. Analysis of interactions between intraflagellar transport proteins. Methods Enzymol. 2013;524:171–194. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-397945-2.00010-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pigino G., Geimer S., Lanzavecchia S., Paccagnini E., Cantele F., Diener D.R., Rosenbaum J.L., Lupetti P. Electron-tomographic analysis of intraflagellar transport particle trains in situ. J. Cell Biol. 2009;187:135–148. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200905103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Corbit K.C., Aanstad P., Singla V., Norman A.R., Stainier D.Y., Reiter J.F. Vertebrate Smoothened functions at the primary cilium. Nature. 2005;437:1018–1021. doi: 10.1038/nature04117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haycraft C.J., Banizs B., Aydin-Son Y., Zhang Q., Michaud E.J., Yoder B.K. Gli2 and Gli3 localize to cilia and require the intraflagellar transport protein polaris for processing and function. PLoS Genet. 2005;1:e53. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0010053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.May S.R., Ashique A.M., Karlen M., Wang B., Shen Y., Zarbalis K., Reiter J., Ericson J., Peterson A.S. Loss of the retrograde motor for IFT disrupts localization of Smo to cilia and prevents the expression of both activator and repressor functions of Gli. Dev. Biol. 2005;287:378–389. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.08.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taipale J., Chen J.K., Cooper M.K., Wang B., Mann R.K., Milenkovic L., Scott M.P., Beachy P.A. Effects of oncogenic mutations in Smoothened and Patched can be reversed by cyclopamine. Nature. 2000;406:1005–1009. doi: 10.1038/35023008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boldt K., van Reeuwijk J., Lu Q., Koutroumpas K., Nguyen T.M., Texier Y., van Beersum S.E., Horn N., Willer J.R., Mans D.A., UK10K Rare Diseases Group An organelle-specific protein landscape identifies novel diseases and molecular mechanisms. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:11491. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.González M., Martín-Ruíz I., Jiménez S., Pirone L., Barrio R., Sutherland J.D. Generation of stable Drosophila cell lines using multicistronic vectors. Sci. Rep. 2011;1:75. doi: 10.1038/srep00075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roux K.J., Kim D.I., Raida M., Burke B. A promiscuous biotin ligase fusion protein identifies proximal and interacting proteins in mammalian cells. J. Cell Biol. 2012;196:801–810. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201112098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rubinson D.A., Dillon C.P., Kwiatkowski A.V., Sievers C., Yang L., Kopinja J., Rooney D.L., Zhang M., Ihrig M.M., McManus M.T. A lentivirus-based system to functionally silence genes in primary mammalian cells, stem cells and transgenic mice by RNA interference. Nat. Genet. 2003;33:401–406. doi: 10.1038/ng1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reimand J., Arak T., Adler P., Kolberg L., Reisberg S., Peterson H., Vilo J. g:Profiler-a web server for functional interpretation of gene lists (2016 update) Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(W1):W83–W89. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tanos B.E., Yang H.J., Soni R., Wang W.J., Macaluso F.P., Asara J.M., Tsou M.F. Centriole distal appendages promote membrane docking, leading to cilia initiation. Genes Dev. 2013;27:163–168. doi: 10.1101/gad.207043.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McCloy R.A., Rogers S., Caldon C.E., Lorca T., Castro A., Burgess A. Partial inhibition of Cdk1 in G 2 phase overrides the SAC and decouples mitotic events. Cell Cycle. 2014;13:1400–1412. doi: 10.4161/cc.28401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wiederschain D., Wee S., Chen L., Loo A., Yang G., Huang A., Chen Y., Caponigro G., Yao Y.M., Lengauer C. Single-vector inducible lentiviral RNAi system for oncology target validation. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:498–504. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.3.7701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spalluto C., Wilson D.I., Hearn T. Evidence for reciliation of RPE1 cells in late G1 phase, and ciliary localisation of cyclin B1. FEBS Open Bio. 2013;3:334–340. doi: 10.1016/j.fob.2013.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sato A., Kishida S., Tanaka T., Kikuchi A., Kodama T., Asashima M., Nishinakamura R. Sall1, a causative gene for Townes-Brocks syndrome, enhances the canonical Wnt signaling by localizing to heterochromatin. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004;319:103–113. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.04.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim D.I., Birendra K.C., Zhu W., Motamedchaboki K., Doye V., Roux K.J. Probing nuclear pore complex architecture with proximity-dependent biotinylation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:E2453–E2461. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1406459111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Van Itallie C.M., Aponte A., Tietgens A.J., Gucek M., Fredriksson K., Anderson J.M. The N and C termini of ZO-1 are surrounded by distinct proteins and functional protein networks. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:13775–13788. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.466193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xue Y., Wong J., Moreno G.T., Young M.K., Côté J., Wang W. NURD, a novel complex with both ATP-dependent chromatin-remodeling and histone deacetylase activities. Mol. Cell. 1998;2:851–861. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80299-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Spektor A., Tsang W.Y., Khoo D., Dynlacht B.D. Cep97 and CP110 suppress a cilia assembly program. Cell. 2007;130:678–690. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kleylein-Sohn J., Westendorf J., Le Clech M., Habedanck R., Stierhof Y.D., Nigg E.A. Plk4-induced centriole biogenesis in human cells. Dev. Cell. 2007;13:190–202. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tsang W.Y., Bossard C., Khanna H., Peränen J., Swaroop A., Malhotra V., Dynlacht B.D. CP110 suppresses primary cilia formation through its interaction with CEP290, a protein deficient in human ciliary disease. Dev. Cell. 2008;15:187–197. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goetz S.C., Liem K.F., Jr., Anderson K.V. The spinocerebellar ataxia-associated gene Tau tubulin kinase 2 controls the initiation of ciliogenesis. Cell. 2012;151:847–858. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Prosser S.L., Morrison C.G. Centrin2 regulates CP110 removal in primary cilium formation. J. Cell Biol. 2015;208:693–701. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201411070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Böhm J., Buck A., Borozdin W., Mannan A.U., Matysiak-Scholze U., Adham I., Schulz-Schaeffer W., Floss T., Wurst W., Kohlhase J., Barrionuevo F. Sall1, sall2, and sall4 are required for neural tube closure in mice. Am. J. Pathol. 2008;173:1455–1463. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.071039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kawakami Y., Uchiyama Y., Rodriguez Esteban C., Inenaga T., Koyano-Nakagawa N., Kawakami H., Marti M., Kmita M., Monaghan-Nichols P., Nishinakamura R., Izpisua Belmonte J.C. Sall genes regulate region-specific morphogenesis in the mouse limb by modulating Hox activities. Development. 2009;136:585–594. doi: 10.1242/dev.027748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Borozdin W., Steinmann K., Albrecht B., Bottani A., Devriendt K., Leipoldt M., Kohlhase J. Detection of heterozygous SALL1 deletions by quantitative real time PCR proves the contribution of a SALL1 dosage effect in the pathogenesis of Townes-Brocks syndrome. Hum. Mutat. 2006;27:211–212. doi: 10.1002/humu.9396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Koster R., Stick R., Loosli F., Wittbrodt J. Medaka spalt acts as a target gene of hedgehog signaling. Development. 1997;124:3147–3156. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.16.3147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Avasthi P., Marshall W.F. Stages of ciliogenesis and regulation of ciliary length. Differentiation. 2012;83:S30–S42. doi: 10.1016/j.diff.2011.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Goetz S.C., Anderson K.V. The primary cilium: a signalling centre during vertebrate development. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2010;11:331–344. doi: 10.1038/nrg2774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liem K.F., Jr., He M., Ocbina P.J., Anderson K.V. Mouse Kif7/Costal2 is a cilia-associated protein that regulates Sonic hedgehog signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:13377–13382. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906944106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.He M., Subramanian R., Bangs F., Omelchenko T., Liem K.F., Jr., Kapoor T.M., Anderson K.V. The kinesin-4 protein Kif7 regulates mammalian Hedgehog signalling by organizing the cilium tip compartment. Nat. Cell Biol. 2014;16:663–672. doi: 10.1038/ncb2988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tunovic S., Barañano K.W., Barkovich J.A., Strober J.B., Jamal L., Slavotinek A.M. Novel KIF7 missense substitutions in two patients presenting with multiple malformations and features of acrocallosal syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2015;167A:2767–2776. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.37249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sohara E., Luo Y., Zhang J., Manning D.K., Beier D.R., Zhou J. Nek8 regulates the expression and localization of polycystin-1 and polycystin-2. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2008;19:469–476. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006090985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Smith L.A., Bukanov N.O., Husson H., Russo R.J., Barry T.C., Taylor A.L., Beier D.R., Ibraghimov-Beskrovnaya O. Development of polycystic kidney disease in juvenile cystic kidney mice: insights into pathogenesis, ciliary abnormalities, and common features with human disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2006;17:2821–2831. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006020136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]