Abstract

Background:

Direct observations with focused feedback are critical components for medical student education. Numerous challenges exist in providing useful comments to students during their clerkships. Students’ evaluations of the clerkship indicated they were not receiving feedback from preceptors or house officers.

Objective:

To encourage direct observation with feedback, Structured Patient Care Observation (SPCO) forms were used to evaluate third-year medical students during patient encounters.

Design:

In 2014-2015, third-year medical students at a Midwestern medical school completing an 8-week pediatrics clerkship provided experiences on inpatient wards and in ambulatory clinics. Students were expected to solicit feedback using the SPCO form.

Results/Findings:

A total of 121 third-year medical students completed the pediatrics clerkship. All of the students completed at least one SPCO form. Several students had more than one observation documented, resulting in 161 SPCOs submitted. Eight were excluded for missing data, leaving 153 observations for analysis. Encounter settings included hospital (70), well-child visits (34), sick visits (41), not identified (8). Observers included attending physicians (88) and residents (65). The SPCOs generated 769 points of feedback, comments coalesced into themes of patient interviews, physical examination, or communication with patients and family. Once themes were identified, comments within each theme were further categorized as either actionable or reinforcing feedback.

Discussion:

SPCOs provided a structure to receive formative feedback from clinical supervisors. Within each theme, reinforcing feedback and actionable comments specific enough to be useful in shaping future encounters were identified.

Keywords: Medical students, actionable feedback, reinforcing feedback, pediatrics, clinical medical education

Background

Medical professionals work in teams and must acquire life-long learning skills to assess their strengths and weaknesses, recognize their limitations, and learn how to remediate areas in need. Reflection on performance is considered a hallmark of self-directed learning.1 However, it has been shown that self-assessment alone can be highly inaccurate.2 To assist learners to improve their knowledge and skills, business literature has shown that specific feedback needs to be provided on learner performance.3

Direct observation with focused feedback is a critical component for clinical medical student education.4 Because feedback is information relayed to students with the intention of improving performance, Harden and Laidlaw5 indicate that feedback will clarify goals, reinforce positive performance, and provide a basis for error correction. Their summary relates to findings from a Delphi process that established a framework for feedback delivery in a clinical setting.6 Their themes emphasizing the relationship between the preceptor and learner as well as learners having specific ideas of how to improve performance rely on the preceptor being present to observe the learner’s performance.

Numerous challenges exist in providing useful comments to students during their clerkships. Physicians have numerous expectations thrust on them, one of which is to teach. Most physicians have not had explicit training on how to effectively communicate feedback. Consequently, feedback may suffer due to competing patient care demands, resulting in feedback that is non-specific and unclear.7

Currently, medical student grades on the pediatrics clerkship are based primarily on summative evaluations provided by faculty and house officers. Despite several faculty development sessions on how to appropriately give feedback, our faculty and residents continue to offer low quality, lenient written feedback or none at all.8 Formal documentation of performance with written comments lacks actionable feedback to improve performance on subsequent clerkships.9 Student comments on the pediatric course evaluations indicated they do not receive formative feedback identifying strengths or weaknesses. On occasions when feedback was provided, it often was received too late to implement corrective measures during the pediatrics clerkship. Milan et al10 found encouraging students to solicit feedback helped improve the specificity of feedback they received. To formalize formative feedback, this study was developed to determine the quality and quantity of feedback statements using a structured format during our pediatrics clerkship. We sought to answer the question, does a structured formative feedback instrument result in specific feedback?

Design

This study considers data collected from the third-year medical students at a Midwestern medical school completing an 8-week pediatrics clerkship during academic year 2014-2015. During the pediatrics clerkship, medical students have experiences on inpatient wards and in ambulatory clinics (general and subspecialty). As students rotated on these services, they were instructed to solicit feedback using the Structured Patient Care Observation (SPCO) form (Figure 1). This study was deemed exempt by the Institutional Review Board.

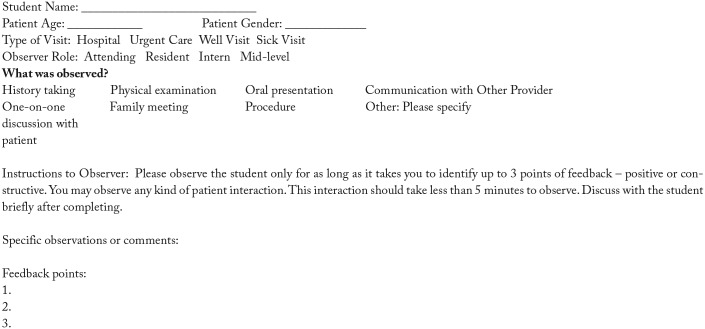

Figure 1.

Structured Patient Care Observation form.

The SPCO was created at the University of Colorado, collecting basic patient information (age, sex), type of visit (inpatient, urgent care, well visit, sick visit), and eight pre-defined options for skills to observe (history taking, physical examination, oral presentation, communication skills, patient counseling, family meeting, procedure, other). Observations could be completed by a physician, house officer, or allied health professional.

At orientation for the clerkship, students were given the SPCO and explained the purpose of the form. One of the authors (J.H.) reviewed the components of the form step by step. Students were instructed to ask their preceptor prior to the patient encounter to observe them and complete the evaluation. It was explained to the students that they will receive a completion grade when it is returned (Pass or Fail), which constituted 5% of the overall clerkship grade.

Prior to the academic year starting, faculty and residents were informed that the SPCO would be used during the clerkship. One of the authors (G.L.B.D.) explained that it was a way to ensure each student receives formative feedback, which had been perceived by students to be lacking. It was clearly explained that these were strictly formative evaluations and would not be part of the final grade. Evaluators were asked to summarize their observation and to provide up to three specific actions a student could take to improve performance. These evaluations were completed immediately after a patient encounter with the student to facilitate face-to-face dialog. The SPCO was turned in to the clerkship coordinator at the end of the clerkship.

All narrative data of these observations were analyzed using crystallization-emersion framework.11 Team members (A.L.R., E.M.L., N.M.K.) independently reviewed comments from each SPCO. The immersion approach allowed each member to document themes they felt emerged from the data. The team met to discuss their impressions from the narrative comments, discussing the various themes they found embedded in the comments. The analysis process continued until consensus was reached on broader themes.

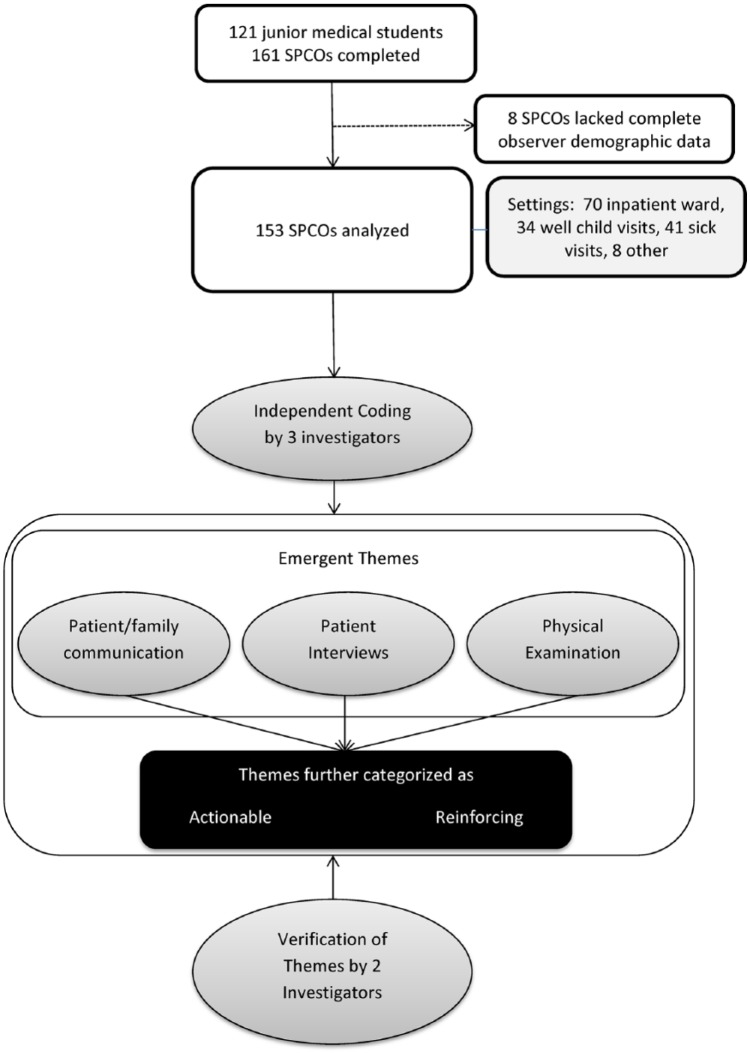

Applying principles from research on feedback,5,6 comments were further categorized as actionable or reinforcing. Feedback was defined as “actionable” for recommendations that students could use to improve future encounters or “reinforcing” for comments of benefit for students but not readily actionable. The other researchers on the team (G.L.B.D., J.H.) then reviewed their findings to determine whether they accurately reflected the comments. Figure 2 summarizes the data collection and analysis process. Exemplar comments for each theme were then chosen from the data.

Figure 2.

Summary of data collection and analysis process.

Results

During academic year 2014-2015, 121 third-year medical students completed the pediatrics clerkship. All of the students completed at least one SPCO form. Several students had more than one observation documented, resulting in 161 SPCOs submitted. Of those, 8 were excluded for lack of accurate observer information, for a total of 153 observations used in the analysis. The encounter settings included hospital (70), well-child visits (34), sick visits (41), and not identified (8). Observers included attending physicians (88) and residents (65).

The SPCOs generated 769 points of feedback, most commonly related to the interview (25.2%), physical examination (16.9%), or interaction with patient and family (15.7%). Actionable comments accounted for 12.4% of responses while reinforcing comments accounted for 87.6%. SPCOs included actionable feedback from 40 (45%) attending physicians and 26 (40%) residents. Sixty-five (64%) attending physicians and 39 (60%) residents gave at least one reinforcing feedback statement.

Three major themes emerged from the data analysis: patient/family communication, patient interviews, and physical examination. For each of these categories, examples of actionable items as well as reinforcing feedback are identified in Table 1. Although there were some non-specific comments (eg, “good job,” “keep reading”), most comments provided more detailed reinforcing or actionable feedback.

Table 1.

Examples of feedback given to students.

| Reinforcing | Actionable | |

|---|---|---|

| Patient/family communication | Great job making mom feel comfortable. She was very stressed before she was sent over—Inpatient Unit | Work to help guide family to achieve information you need but if you sense they have specific concerns it is okay to reassure any time—Sick Visit |

| Patient interviews | Very good job with history gathering. Good differential for level of training—Sick Visit | Work on efficiency (will come with experience). Develop treatment plans as you get more comfortable—Sick Visit |

| Physical examination | Good use of toys and equipment to get good neuro examination on patient—Inpatient Unit | Adjust developmental expectation depending on corrected gestation age—Well Visit |

Discussion

In an effort to provide more formal feedback to medical students during their pediatrics clerkship, we employed the SPCO form, requiring at least one observation during the 8-week course. Our findings indicated students received specific, actionable feedback as well as specific reinforcing feedback (eg, “She knew the exam and did most of the elements. She did forget a few elements and these were reviewed with her. Pointers were given on working with young children who are not cooperative.”). Feedback was provided in different patient care settings and was primarily provided by attending physicians.

For our first attempt at integrating this feedback process into the clerkship, we were primarily expecting to see non-specific, reinforcing comments. This expectation stemmed from comments written on final clinical performance evaluations, which were either left blank or consisted of “good job” or “read more.” Much to our surprise, comments were much more specific, meeting established criteria for effective feedback.12 Specifically, providing expected and timely feedback for patient encounters that were directly observed allowed students to receive input on specific performance.

Reinforcing feedback was found to be an important aspect in this study. These types of comments provided positive support for work students completed. Comments such as “Good flow to questions, follow up on parent concern, good blend open/closed questions” or “Let patient/caregiver tell ‘story’” provide encouragement for skills that were done well. This type of feedback is intended to encourage exhibiting these types of behaviors and skills going into future patient encounters.

As noted from the results, actionable comments were detailed enough so that students knew how to improve their skills. According to Johnson et al,6 our feedback process aligned with key elements they identified, such as identifying how the student’s performance deviates from expected standards, preceptor comments are specific and useful for students, and comments relate to the task and are not personal. For example, this comment exemplifies these elements, “Think about why patient presented and ask more detailed questions related to chief complaint.”

What we did find lacking in the SPCO was an accountability step where the learner could indicate a goal to achieve correcting the actionable feedback provided. This may have occurred in the dialog with the observer, but it was not specifically spelled out on the form. This oversight limited our ability to assess whether the students enacted their plan. Unfortunately, due to time constraints of the clerkship, it may not be logistically possible to do that.

We have found that using the SPCO to have more structure for students to receive feedback was highly successful. The specific comments for students showed marked improvement from what we had previously seen on clinical evaluations. It was noted that there were fewer actionable comments than reinforcing comments. Since the only evaluation preceptors completed prior to implementing the SPCO were for final grades, we suspect this may have led to providing more reinforcement over actionable recommendations.

In addition, faculty development programs have traditionally focused on what is often referred to as a feedback sandwich, wherein the faculty has been trained to give a reinforcing statement, an actionable statement, then close with the reinforcing statement. It may be better to provide either one or the other and not both. Although this approach to feedback is considered the standard,12,13 a different approach for a new generation of learners may be needed.

In addition to this study highlighting specific feedback of greater quality than expected, it also identified a way to better train faculty.14 The feedback that was documented clarified goals, reinforced good performance, and provided actionable steps for improvement.5 However, goal setting with a clearly articulated action plan was lacking.6,12 In the past, training on how to give feedback focused solely on delivery and lacked any steps for a plan and follow up. These 2 steps in planned faculty development sessions may enhance feedback provided to medical students.

This study was conducted at a single institution so our results may not be generalizable. However, the process used to obtain feedback using the SPCO could be undertaken, particularly for documentation of direct observation followed by feedback. Using this process, students not only have a specific assignment for being observed, but they also have an expectation of receiving verbal and written critique of their clinical skills.

Using the SPCO resulted in a higher incidence of specific reinforcing and actionable feedback. While actionable feedback remained less than reinforcing, both forms of feedback were more detailed. The use of the SPCO therefore encouraged a higher quality of feedback for learners than previously seen on prior student performance evaluations. The SPCO was easily modified for our clerkship and has the potential to be used in other courses. Future efforts will focus on training faculty and house officers to help medical students set reasonable learning plans to apply the feedback received and follow up with repeated observation.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Evan M. Lackore and Nora M. Kovar for working with Dr Reinhardt to analyze the narrative comments.

Footnotes

Declaration Of Conflicting Interests:The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding:The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author Contributions: GLBD and JH contributed to the study concept, design, and coordination and data collection and analysis. GLBD and JH wrote the first draft of the manuscript, edited, and made revisions. AR made study collaboration, data collection and analysis, and manuscript revision and editing. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1. Lurie SJ, Meldrum S, Nofziger AC, Sillin LF, III, Mooney CJ, Epstein RM. Changes in self-perceived abilities among male and female medical students after the first year of clinical training. Med Teach. 2007;29:921–926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Eva K, Regehr G. Exploring the divergence between self-assessment and self-monitoring. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2011;16:311–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nawaz N, Jahanian A, Manzoor SW. Critical elements of the constructive performance feedback: an integrated model. Euro J Bus Manag. 2012;4:76–84. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Moss HA, Derman PB, Clement RC. Medical student perspective: working toward specific and actionable clinical clerkship feedback. Med Teach. 2012;34:665–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Harden RM, Laidlaw JM. Be FAIR to students: four principles that lead to more effective learning. Med Teach. 2013;35:27–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Johnson CE, Keating JL, Boud DJ, et al. Identifying educator behaviours for high quality verbal feedback in health professions education: literature review and expert refinement. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16:96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Canavan C, Holtman MC, Richmond M, Katsufrakis PJ. The quality of written comments on professional behaviors in a developmental multisource feedback program. Acad Med. 2010;85:S106–S109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bing-You R, Varaklis K, Hayes V, Trowbridge R, Kemp H, McKelvy D. The feedback tango: an integrative review and analysis of the content of the teacher-learner feedback exchange [published online ahead of print October 3, 2017]. Acad Med. doi:101097/ACM0000000000001927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fazio SB, Torre DM, DeFer TM. Grading practices and distributions across internal medicine clerkships. Teach Learn Med. 2016;28:286–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Milan FB, Dyche L, Fletcher J. “How am I doing?” Teaching medical students to elicit feedback during their clerkships. Med Teach. 2011;33:904–910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Creswell JW. Research Design: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ende J. Feedback in clinical medical education. JAMA. 1983;250:777–781. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ramani S, Krackov SK. Twelve tips for giving feedback effectively in the clinical environment. Med Teach. 2012;34:787–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mohanaruban A, Flanders L, Rees H. Case-based discussion: perceptions of feedback. Clin Teach. 2017;15:126–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]