Abstract

Background

Quantitative real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction has been widely used in gene expression analysis, however, to have reliable and accurate results, reference genes are necessary to normalize gene expression under different experimental conditions. Several reliable reference genes have been reported in plants of Traditional Chinese Medicine, but none have been identified for Euscaphis konishii Hayata.

Results

In this study, 12 candidate reference genes, including 3 common housekeeping genes and 9 novel genes based on E. konishii Hayata transcriptome data were selected and analyzed in different tissues (root, branch, leaf, capsule and seed), capsule and seed development stages. Expression stability was calculated using geNorm and NormFinder, the minimal number of reference genes required for accurate normalization was calculated by Vn/Vn + 1 using geNorm. EkEEF-5A-1 and EkADF2 were the two most stable reference genes for all samples, while EkGSTU1 and EkGAPDH were the most stable reference genes for tissue samples. For seed development stages, EkGAPDH and EkEEF-5A-1 were the most stable genes, whereas EkGSTU1 and EkGAPDH were identified as the two most stable genes in the capsule development stages. Two reference genes were sufficient to normalize gene expression across all sample sets.

Conclusion

Results of this study revealed that suitable reference genes should be selected for different experimental samples, and not all the common reference genes are suitable for different tissue samples and/or experimental conditions. In this study, we present the first data of reference genes selection for E. konishii Hayata based on transcriptome data, our data will facilitate further studies in molecular biology and gene function on E. konishii Hayata and other closely related species.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s13007-018-0311-x) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Euscaphis konishii Hayata, Reference gene, qRT-PCR, Transcriptome, Gene expression, Normalization, EkCAD1 gene

Background

Quantitative real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) has become one of the most powerful tools to study gene expression due to its high sensitivity, accuracy and specificity [1]. However, to get accurate and reliable results, a reference gene is necessary to normalize gene expression and avoid errors caused by different experimental procedure, such as sample amounts, quality and quantity of RNA, efficiency of enzymatic reaction and PCR efficiency [2, 3].

Most of the commonly used reference genes are housekeeping genes, such as actin (ACT), tubulin (TUB), polyubiquitin (BUQ), elongation factor 1-α (EF1-α), glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and ribosomal RNAs (18S rRNA or 28S rRNA). However, some data showed that expression levels of these housekeeping genes can vary considerably under different experimental conditions [4, 5], and also, in non-model plant species, usually the used reference genes are identified by the orthologous sequence of common housekeeping genes reported in model plant species due to the lack of genetic and sequence genome information [6]. Consequently, the unsuitable use of traditional housekeeping genes as reference gene in non-model plants can cause bias. Therefore, it is important to select proper reference genes according to experimental conditions [7]. Moreover, statistical software, including geNorm, BestKeeper, NormFinder and RefFinder, have been widely used as efficient tools to evaluate gene expression stability for qRT-PCR normalization [8–10]. Reference gene validation has been done in many plant species, such as banana [11], peach [12], soybean [13], amorphophallus [14], Jatropha curcas [15], Isatis indigotica Fort. [16], Achyranthes bidentata Blume [17], Kentucky bluegrass [18], Salix matsudana [19], Rhododendron molle G. Don [20], Sapium sebiferum [21], Petroselinum crispum [22], Lilium spp. [23], Hibiscus cannabinus L. [24] and Dendrobium officinale [25].

Euscaphis is a member of the family Staphyleaceae, which has two species in China: E. japonica Dippel and E. konishii Hayata. Euscaphis has been widely used in traditional Chinese medicine. Several chemical compounds have been isolated from Euscaphis, such as triterpene compounds [26–29], phenolic acid compounds [30, 31], flavonoid compounds [27, 31] and others [31–33], however, no molecular and gene expression data has been reported in Euscaphis.

Twelve genes (EkUBC, EkF-ACP, EkARP7, EkEF2, EkACT, EkGAPDH, EkEEF-5A-1, EkADF2, EkTUB, EkPLAC8, EkLPP, EkGSTU1) were selected as candidate genes according to transcriptome data from our lab (Liang et al., College of Forestry, Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University) (unpublished data), and their expression stability was evaluated by qRT-PCR across different experimental conditions: including five tissues (root, branch, seed, leaf and capsule), six different developmental stages of seed and six different development stages of capsule. Their expression stability was calculated using geNorm and NormFinder. Additionally, in order to validate our results, the expression levels of EkCAD1 in different tissues were normalized by the most and least stable genes.

Methods

Plant material

Euscaphis konishii Hayata tissues were collected from Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University, Fujian Province, China. Tissues (leaf, capsule, seed, root and branch) were collected on November 15th 2016, and six developmental stages of capsule and seed were collected once every 15 days after formation. All samples were harvested, washed and surface dried and then frozen in liquid nitrogen and immediately stored at − 80 °C until required for further analyzes. Three biological replicates for each sample were used for RNA extraction.

RNA isolation and cDNA synthesis

Total RNA was extracted from each sample using the RNAprepPure Plant Kit DP441 (Tiangen Biothch CO., LTD, Beijing, China), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA was treated with DNase I (Tiangen, Beijing, China) to eliminate DNA contamination. RNA quality was determined by 1.2% agarose gel electrophoresis. The concentration and purity of total RNA was determined using a NanoDrop 2000c Spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, US). The A260/A280 ratio of total RNA between 1.90 and 2.10 was considered to meet the required quality for further experiments. First-strand of cDNA was synthesized using the First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Roche, Switzerland) using 1.0 μg of total RNA in a 20 μL reaction volume according to the manufacturer’s protocols.

Selection of candidate reference genes and primer design

Based on transcriptome sequencing data from our laboratory, 12 reference genes were selected to normalize and validate qRT-PCR experiments by screening for genes with relatively stable expression (based on their RPKM and fold change values), including nine novel genes and three common housekeeping genes. Their sequence/alignment/phylogenetic data are shown in Additional files 1 and 2. Forward and reverse primers of all candidate reference genes were designed using Primer Premier 5.0 with the following parameters: Tm values ranging from 50 to 70 °C, GC percent of 45–50%, primer lengths of 18–25 bp and product length of 90–200 bp. All primers were synthesized by Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China). Primer details are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primers used for qRT-PCR normalization

| Gene abbreviation | Gene name | Primer sequence (5′–3′) | Amplicon length (bp) | Primers Tm (°C) | E (%) | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EkUBC | E. konishii Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2-17 kDa | For: TCTGCAGGTCCTTCAATTCC | 100 | 54.8/54.8 | 97.89 | 0.9998 |

| Rev: CGCAAACCCTAGAGAGAGTAAG | ||||||

| EkF-ACP | E. konishii F-actin capping protein alpha subunit | For: CCAGTAACTCGCACCCTATTT | 96 | 54.44/54.56 | 99.59 | 0.9994 |

| Rev: TCACTGTCACTTTCCGATTCC | ||||||

| EkARP7 | E. konishii Actin-related protein 7 | For: CCTTCATTACCCATCTCCCATC | 100 | 55.03/53.41 | 99.35 | 0.9878 |

| Rev: CTAATGAATCCTCGTATGACTGGAT | ||||||

| EkEF2 | E. konishii Elongation factor 2 | For: GAGAGCGACAAGGGAATGAG | 108 | 55.7/54.8 | 100.09 | 0.9997 |

| Rev: TATTACTGATGGTGCGCTGG | ||||||

| EkACT | E. konishii Actin | For: CATTGTGAGCAACTGGGATG | 125 | 54.01/54.21 | 103.21 | 0.9998 |

| Rev: GATTAGCCTTCGGGTTGAGA | ||||||

| EkGAPDH | E. konishii Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | For: TGGCTTTCCGTGTTCCTACT | 113 | 56.14/57.12 | 101.1 | 0.9795 |

| Rev: TCCCTCTGACTCCTCCTTGA | ||||||

| EkEEF-5A-1 | E. konishii Eukaryotic elongation factor 5A-1 | For: TCCGACATAGCTCCGATTCA | 101 | 55.42/55.4 | 98.46 | 0.9991 |

| Rev: GAAGAGACGGAGAGGAGAGATT | ||||||

| EkADF2 | E. konishii Actin-depolymerizing factor 2 | For: CCGAAGAGAATGTCCAGAAGAG | 98 | 54.97/54.48 | 99.89 | 0.9998 |

| Rev: GTCCTTTGAGCTCGCATAGAT | ||||||

| EkTUB | E. konishii β-Tubulin | For: AAAGATGAGCACCAAGGAGGT | 108 | 56.18/55.60 | 98.69 | 0.9879 |

| Rev: TCACACACGCTGGATTTCAC | ||||||

| EkPLAC8 | E. konishii PLAC8 family protein isoform 2 | For: GGGAATCGGAGGTAAAGATCAA | 102 | 54/54 | 99.00 | 0.9822 |

| Rev: TGGATCTGAAGAAATGGGAGAC | ||||||

| EkLPP | E. konishii Lonprotease-2-like protein | For: TTGGCCTCATCTATTGCTACTG | 98 | 54.3/55.4 | 101.00 | 0.9931 |

| Rev: GTTCTCCTGTGCCCTCTAATG | ||||||

| EkGSTU1 | E. konishii Glutathione-S-transferase tau 1 | For: GCCCTCATCCCAAACATACT | 113 | 54.6/54 | 98.99 | 0.9999 |

| Rev: GAGATTGTTTGCAGCGAATAGG | ||||||

| EkCAD1 | E. konishii Cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase 1 | For: GTGGGCTTTCCGTCAGTGTA | 123 | 59.97/59.97 | 99.23 | 0.9969 |

| Rev: GGTCGGAGTTGGAGCTATCG |

qRT-PCR analysis for each candidate reference gene was performed on a 7500 Fast ABI Real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, US) using FastStart Universal SYBR Green Master (Roche, Switzerland). A 20 μL reaction mixture contained: 10 μL 2 × SYBR Green Master, 0.4 μL forward primer (10 μM), 0.4 μL reverse primer (10 μM), 2 μL cDNA and 7.2 μL dd H2O in a 96-well plates. The amplification conditions were as follows: 50 °C for 2 min, 95 °C for 10 min, 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for 30 s. Melting curve was analyzed to determine primer specificity.

All samples were analyzed in three biological and technical replicates. Serial tenfold dilutions of cDNA template were used to generate slope of the standard curve to calculate amplification efficiency and correlation coefficient of each candidate reference gene.

Data analysis

NormFinder and geNorm were used to analyze the stability of the 12 candidate reference genes under different conditions. Expression levels of each reference gene were shown by Cq values. Before using the two softwares, the raw Cq values was used to calculate relative quantities by the equation: Q = 2−(sampleCq-mimCq). The values of stability (M) and pairwise variation (V) between genes was generated by geNorm, the lower M value is the gene expression is more stable [8, 34, 35]. Furthermore, the normalization factor generated by computing the pairwise variation of the two normalization factor was used to determine the most suitable numbers of reference genes with a cut-off value of 0.15 [17]. NormFinder was used to evaluate the stability of candidate genes by intra- and inter- group variations. The more stable reference gene will have lower stability value and inter- and intra-group variation.

Validation of the candidate reference genes

In order to verify the results of our experiments, the most stable and unstable reference genes were selected to validate the expression of the E. konishii Cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase 1 (EkCAD1) gene in different tissue samples (root, branch, capsule, seed and leaf). CAD1 belongs to CAD family, which catalyzes the reduction of p-coumaricaldehyde, coniferyl aldehyde and sinapyl aldehyde to their alcohol derivatives which are then polymerized into lignin [36], CAD is one of the most used genes to manipulate to obtain plants with low lignin content [37]. qRT-PCR experimental method was the same as described above, and the relative expression level was calculated by 2−ΔΔct method [12]. Data from three biological replicates were analyzed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Student’s t test (P < 0.05).

Results

Primer specificity and PCR amplification efficiency

A total of 12 candidate reference genes, including three common housekeeping genes and nine novel genes from transcriptome sequencing data of E. konishii were selected for qRT-PCR normalization. The details of gene names, abbreviation, accession number, primer sequence, primers Tm, product length, amplification efficiency and correlation coefficient are shown in Table 1. The specificity for each primer set was validated by melting curve. For all primer sets the melting curve showed a single amplification peak (Additional file 3). qRT-PCR efficiency for all 12 candidate reference genes ranged from 97.89% for EkUBC to 103.21% for EkACT, and correlation coefficients varied from 0.9795 to 0.9999 (Table 1).

Cq values of candidate reference genes

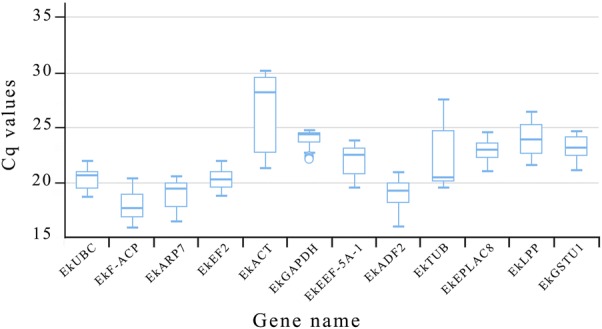

Cq values for all 12 reference genes are shown in Fig. 1. The Cq values varied from 15.812 (EkF-ACP) to 30.121 (EkACT) across all samples, and mean Cq ranged from 18.0575 (EkF-ACP) to 25.6685 (EkACT). Moreover, EkACT expression levels were the most variable with 8.905 Cq, while EkGAPDH showed the least variable levels with 2.609 Cq. Since gene expression levels are negatively correlated to Cq values, EkF-ACP had high expression and EkACT with low expression.

Fig. 1.

Cq values of the twelve candidate reference genes. The lines across the box indicate median values, boxes depict 25/75 percentiles. Whisker caps indicate the minimum and maximum values

Expression stability of candidate reference genes

Expression stability of the 12 reference genes was analyzed by geNorm and NormFinder. Samples were divided into three different experimental groups: (1) five tissues (root, leaf, branch, seed and capsule), (2) six seed developmental stages and (3) six capsule developmental stages.

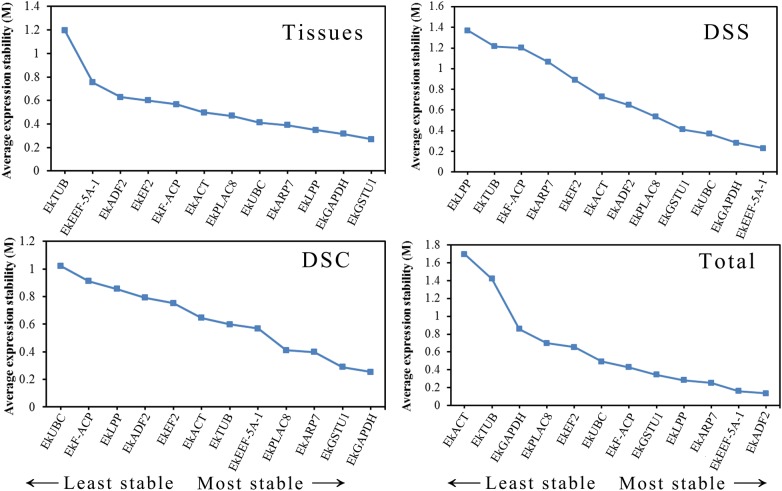

geNorm analysis

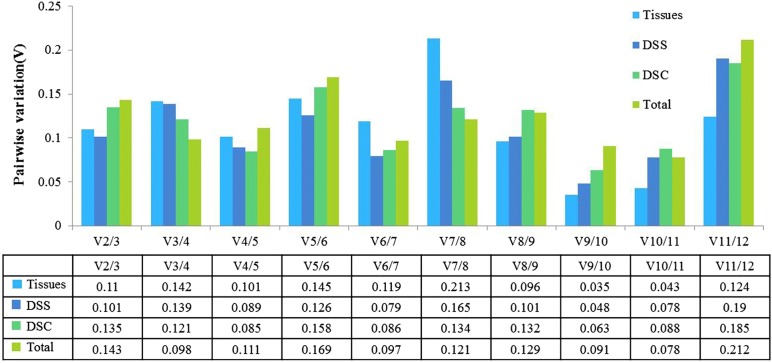

Gene expression stability was determined by M-value in geNorm analysis, the lower the M value is, the more gene expression stability. For the tissue group the two most stable genes were EkGSTU1 and EkGAPDH with the lowest M value, and EkTUB was the most unstable gene. In the seed group EkEEF-5A-1 and EkGAPDH were the two most stable genes through all the different developmental stages, and EkLPP was the most unstable gene. Finally, in the capsule group EkGAPDH was the most stable gene, followed by EkGSTU1, and EkF-ACP and EkUBC were the least stable genes (Table 2; Fig. 2). For all sample sets EkADF2 and EkEEF-5A-1 were the most stable genes, and EkF-ACP and EkUBC were the least stable. The minimum number of genes required for normalization in all the different groups was calculated by geNorm. The V2/3 values for all different experimental groups were below the cut-off value of 0.15 (0.143 of all samples, 0.11 for tissues samples, 0.101 for seed development stages and 0.135 for capsule development stages), which indicate that two reference genes are enough to normalize gene expression data (Fig. 3).

Table 2.

Gene expression stability across sample sets calculated by geNorm

| Gene name | Different tissues | Seed development stages | Capsule development stages | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EkUBC | 0.412 (5) | 0.369 (3) | 1.023 (12) | 0.491 (7) |

| EkF-ACP | 0.568 (8) | 1.201 (10) | 0.911 (11) | 0.428 (6) |

| EkARP7 | 0.390 (4) | 1.065 (9) | 0.398 (3) | 0.251 (3) |

| EkEF2 | 0.599 (9) | 0.890 (8) | 0.753 (8) | 0.655 (8) |

| EkACT | 0.498 (7) | 0.729 (7) | 0.646 (7) | 1.698 (12) |

| EkGAPDH | 0.315 (2) | 0.283 (2) | 0.254 (1) | 0.858 (10) |

| EkEEF-5A-1 | 0.752 (11) | 0.231 (1) | 0.568 (5) | 0.159 (2) |

| EkADF2 | 0.629 (10) | 0.649 (6) | 0.792 (9) | 0.134 (1) |

| EkTUB | 1.198 (12) | 1.216 (11) | 0.599 (6) | 1.421 (11) |

| EkPLAC8 | 0.469 (6) | 0.534 (5) | 0.412 (4) | 0.699 (9) |

| EkLPP | 0.348 (3) | 1.368 (12) | 0.855 (10) | 0.284 (4) |

| EkGSTU1 | 0.269 (1) | 0.412 (4) | 0.289 (2) | 0.344 (5) |

Fig. 2.

Average expression stability (M-value) of 12 candidate genes calculated by geNorm and ranking of the candidate reference genes in different experimental group. Tissues: five tissues sample sets; DSS: seed development stages; DSC: capsule development stages. Total: all samples

Fig. 3.

Optimal number of reference genes in different experimental groups using the geNorm. Pairwise variation (Vn/Vn + 1) analysis between normalization factors (NFn and NFn + 1) to calculate the number of reference genes in each experimental group. Tissues: five tissues sample sets; DSS: seed development stages; DSC: capsule development stages. Total: all samples

NormFinder analysis

Expression stability values analyzed by NormFinder are shown in Table 3. For tissue group, EkGSTU1 and EkGAPDH were the most stable reference genes, and EkTUB was the least stable gene, same as shown by geNorm analysis. In the seed group EkEEF-5A-1 and EkGAPDH were the most stable reference genes, while EkARP7 was the least stable gene. In the capsule group, EkGAPDH and EkGSTU1 got the top rank, while EkUBC and EkF-ACP were ranked at the lowest. In general, the ranking was same as geNorm analysis (Table 3).

Table 3.

Gene expression stability across sample sets calculated by NormFinder

| Gene name | Different tissues | Seed development stages | Capsule development stages | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EkUBC | 0.268 (6) | 0.239 (3) | 0.391 (11) | 0.274 (8) |

| EkF-ACP | 0.331 (7) | 0.392 (10) | 0.414 (12) | 0.201 (6) |

| EkARP7 | 0.256 (3) | 0.601 (12) | 0.178 (3) | 0.103 (4) |

| EkEF2 | 0.367 (9) | 0.521 (11) | 0.369 (8) | 0.348 (9) |

| EkACT | 0.546 (11) | 0.379 (9) | 0.365 (7) | 1.495 (12) |

| EkGAPDH | 0.240 (2) | 0.171 (2) | 0.102 (1) | 0.493 (10) |

| EkEEF-5A-1 | 0.338 (8) | 0.153 (1) | 0.295 (6) | 0.090 (2) |

| EkADF2 | 0.458 (10) | 0.358 (8) | 0.384 (10) | 0.035 (1) |

| EkTUB | 0.806 (12) | 0.349 (7) | 0.286 (5) | 1.131 (11) |

| EkPLAC8 | 0.261 (5) | 0.273 (4) | 0.251 (4) | 0.259 (7) |

| EkLPP | 0.256 (3) | 0.302 (6) | 0.371 (9) | 0.102 (3) |

| EkGSTU1 | 0.165 (1) | 0.285 (5) | 0.116 (2) | 0.159 (5) |

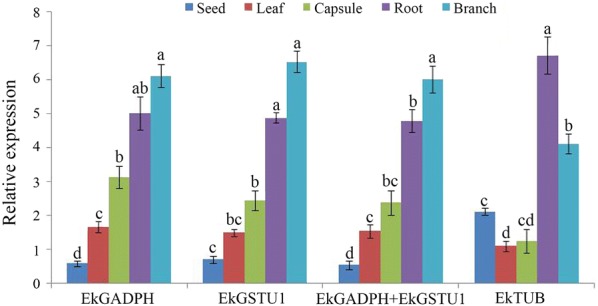

EkCAD1 expression and validation of EkGSTU1 and EkGAPDH

In order to verify the reliability of the selected reference genes, expression profiles of EkCAD1 gene was determined in different tissues. Relative expression levels were normalized using the two most stable reference genes (EkGSTU1 and EkGAPDH) and the least stable reference gene (EkTUB).

EkCAD1 showed similar expression levels when single or a combination of reference genes (EkGSTU1 and EkGAPDH) were used to normalize the expression. EkCAD1 expression was up regulated in all the tissues except in seed. However, when EkTUB was used for normalization (unstable gene), relative expression profile of EkCAD1 was different when compared when the normalization expression was done using the two most stable reference genes identified in our study (EkGSTU1 and EkGAPDH) (Fig. 4). Our results suggest that the expression patterns of target genes are differed when normalized by different reference genes.

Fig. 4.

Relative expression of EkCAD1 in different tissues. EkGSTU1, EkGAPDH and EkGSTU1 + EkGAPDH were used as one or two most stable reference genes, EkTUB was used as the least stable reference gene. Data are represented as mean ± SD, different words indicate significant difference of the expression of the target gene based on three biological replications (P < 0.05, t test; n = 3)

Discussion

qRT-PCR is one of the most commonly used technique to determine gene expression in plants. To ensure the accuracy and reliability of the results, a suitable reference gene is necessary for data normalization. Conventionally, some housekeeping genes such as ACT, GAPDH, TUB, have been used as reference genes, however, no single gene can be used for all plant species, experimental conditions and/or tissues. Therefore, it is required to select proper reference gene(s) for certain species under different conditions rather than using common reference genes.

The development of high-throughput sequencing technology provides a more efficient approach to study plant molecular biology, and it has been widely used in plant genomes [38–43], plant transcriptome [44–47], plant ncRNA [48–50], moreover, the generation of large-scale gene segments and gene expression data by sequencing provides a new resource for the identification of reference genes, especially in non-model species [51–53]. Therefore, transcriptome data on E. konishii Hayata, available in our laboratory can be used as a tool to identify candidate reference genes. Asystematic study of 12 candidate reference genes in three conditions was carried in this paper, and their expression stability was calculated using geNorm and NormFinder.

ACT and TUB, the most widely used reference genes, did not show a good expression stability in E. konishii Hayata across all sample sets (Tables 2, 3). The phenomenon that expression levels of common reference genes varied in a large range has been reported in several papers [54, 55]. GAPDH, a common housekeeping gene also, has been widely used as reference gene in different species and experimental conditions [51, 56–60], in our experiments this gene was one of the two most stable genes in tissue sample set and capsule development stages, but it did not perform well in across all the sample and seed sets. The different performance of EkGAPDH in different experimental conditions in this study demonstrated that there is no single reference gene that can be used for all species or different experimental conditions [61–65].

In this study, EkGSTU1 (glutathione-S-transferase tau 1), which belongs to tau class of glutathione transferases (GSTs) [66], was the one of two most stable genes in tissues sample and capsule development stages. EkADF2 and EkEEF-5A-1 were the two most stable genes in total sample set, ADF (actin-depolymerizing factor) play important roles in several cellular processes that require cytoskeletal rearrangements, such as cell migration, chromosome introgression, cleavage plane orientation and furrow formation [67–69]. VvADF has been identified as candidate reference gene for grapevine during anthesis [6], rubber tree duration of latex flow [70] and TrADF3 was selected as reference gene in staminate and perfect flowers of T. rupestris [71].

It has been widely accepted that using combination of multiple reference genes to normalize gene expression can give more accurate and reliable expression patterns than using a single gene in qRT-PCR analysis [57]. Based on validation results of target gene expression, when EkGAPDH and EkGSTU1 were selected as reference genes for normalization either single or combination, the target gene EkCAD1 showed the similar expression pattern among different tissues, which indicated that the expression pattern of EkCAD1 was nearly identical when normalized with a single reference gene or two. Interestingly, in the tissue group, the combination of traditional housekeeping gene (EkGAPDH) and a novel identified reference gene (EkGSTU1) were identified as the most stable reference genes, suggesting that combination of traditional housekeeping genes and newly identified reference genes based on transcriptome data can be used as a good strategy for expression normalization of E. konishii Hayata genes.

Conclusion

In this study, we evaluated the expression stability of twelve candidate reference genes, including three traditional housekeeping genes and nine novel genes based on transcriptome data of E. konishii Hayata. Additionally, the expression pattern of target gene EkCAD1 was determined in different tissues to further verify the reliability of the identified stable reference genes. This study shows the first data for reference genes validation on E. konishii Hayata. Our study will contribute in future studies of gene expression in E. konishii Hayata and related species.

Additional files

Additional file 1. Sequences of 12 candidate genes and 1 validation gene.

Additional file 2. Alignment and phylogenetic tree of 12 candidate genes and 1 validation gene.

Additional file 3. Melting curves for the 12 candidate reference genes.

Authors’ contributions

WXL, XXZ, CLR, SQW and SQZ designed the experiments, LJW, XYY, WHS and HD selected the material, WXL, LJW, WHS and WH performed the experiments, WXL, XYY, HD, PFL, LN and WH analyzed the data, WXL, SQZ wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions and description of a complete protocol are included within the article.

Consent for publication

All authors have consented for publication.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation of China Projects (Grant No. 31700292), the Special fund for science and technology innovation of Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University (Project Nos. CXZX2016072, CXZX2016073, CXZX2016074).

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s13007-018-0311-x) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Wenxian Liang, Email: lwx_fjfafu@126.com.

Xiaoxing Zou, Email: 448962113@qq.com.

Rebeca Carballar-Lejarazú, Email: rebecacarballar@gmail.com.

Lingjiao Wu, Email: 294722245@qq.com.

Weihong Sun, Email: 805975719@qq.com.

Xueyuan Yuan, Email: 1763576956@qq.com.

Songqing Wu, Email: dabinyang@126.com.

Pengfei Li, Email: 753402868@qq.com.

Hui Ding, Email: 1281589557@qq.com.

Lin Ni, Email: nilin_fjau@126.com.

Wei Huang, Email: weiyena2001@gmail.com.

Shuangquan Zou, Email: zou@fafu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Bustin SA. Quantification of mRNA using real-time reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR): trends and problems. J Mol Endocrinol. 2002;29(1):23–39. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0290023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Die JV, Roman B, Nadal S, Gonzalez-Verdejo CI. Evaluation of candidate reference genes for expression studies in Pisum sativum under different experimental conditions. Planta. 2010;232(1):145–153. doi: 10.1007/s00425-010-1158-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schmidt GW, Delaney SK. Stable internal reference genes for normalization of real-time RT-PCR in tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) during development and abiotic stress. Mol Genet Genom. 2010;283(3):233–241. doi: 10.1007/s00438-010-0511-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bustin SA, Nolan T. Pitfalls of quantitative real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction. J Biomol Tech. 2004;15(3):155–166. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gutierrez L, Mauriat M, Guenin S, Pelloux J, Lefebvre JF, Louvet R, Rusterucci C, Moritz T, Guerineau F, Bellini C, et al. The lack of a systematic validation of reference genes: a serious pitfall undervalued in reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis in plants. Plant Biotechnol J. 2008;6(6):609–618. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2008.00346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gonzalez-Aguero M, Garcia-Rojas M, Di Genova A, Correa J, Maass A, Orellana A, Hinrichsen P. Identification of two putative reference genes from grapevine suitable for gene expression analysis in berry and related tissues derived from RNA-Seq data. BMC Genom. 2013;14:878. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jian B, Liu B, Bi Y, Hou W, Wu C, Han T. Validation of internal control for gene expression study in soybean by quantitative real-time PCR. BMC Mol Biol. 2008;9:59. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-9-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vandesompele J, De Preter K, Pattyn F, Poppe B, Van Roy N, De Paepe A, Speleman F. Accurate normalization of real-time quantitative RT-PCR data by geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes. Genome Biol. 2002;3(7):Research0034. doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-7-research0034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andersen CL, Jensen JL, Orntoft TF. Normalization of real-time quantitative reverse transcription-PCR data: a model-based variance estimation approach to identify genes suited for normalization, applied to bladder and colon cancer data sets. Can Res. 2004;64(15):5245–5250. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pfaffl MW, Tichopad A, Prgomet C, Neuvians TP. Determination of stable housekeeping genes, differentially regulated target genes and sample integrity: BestKeeper–Excel-based tool using pair-wise correlations. Biotechnol Lett. 2004;26(6):509–515. doi: 10.1023/B:BILE.0000019559.84305.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen L, Zhong HY, Kuang JF, Li JG, Lu WJ, Chen JY. Validation of reference genes for RT-qPCR studies of gene expression in banana fruit under different experimental conditions. Planta. 2011;234(2):377–390. doi: 10.1007/s00425-011-1410-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tong Z, Gao Z, Wang F, Zhou J, Zhang Z. Selection of reliable reference genes for gene expression studies in peach using real-time PCR. BMC Mol Biol. 2009;10:71. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-10-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gao M, Liu Y, Ma X, Shuai Q, Gai J, Li Y. Evaluation of reference genes for normalization of gene expression using quantitative RT-PCR under aluminum, cadmium, and heat stresses in soybean. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(1):e0168965. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0168965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang K, Niu Y, Wang Q, Liu H, Jin Y, Zhang S. Cloning and evaluation of reference genes for quantitative real-time PCR analysis in Amorphophallus. PeerJ. 2017;5:e3260. doi: 10.7717/peerj.3260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karuppaiya P, Yan XX, Liao W, Wu J, Chen F, Tang L. Correction: identification and validation of superior reference gene for gene expression normalization via RT-qPCR in staminate and pistillate flowers of Jatropha curcas—a biodiesel plant. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(5):e0177039. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0177039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li T, Wang J, Lu M, Zhang T, Qu X, Wang Z. Selection and validation of appropriate reference genes for qRT-PCR analysis in Isatis indigotica Fort. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:1139. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.01139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li J, Han X, Wang C, Qi W, Zhang W, Tang L, Zhao X. Validation of suitable reference genes for RT-qPCR data in Achyranthes bidentata Blume under different experimental conditions. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:776. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Niu K, Shi Y, Ma H. Selection of candidate reference genes for gene expression analysis in Kentucky Bluegrass (Poa pratensis L.) under abiotic stress. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:193. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang Y, Han X, Chen S, Zheng L, He X, Liu M, Qiao G, Wang Y, Zhuo R. Selection of suitable reference genes for quantitative real-time PCR gene expression analysis in Salix matsudana under different abiotic stresses. Sci Rep. 2017;7:40290. doi: 10.1038/srep40290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xiao Z, Sun X, Liu X, Li C, He L, Chen S, Su J. Selection of reliable reference genes for gene expression studies on Rhododendron molle G. Don. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:1547. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen X, Mao Y, Huang S, Ni J, Lu W, Hou J, Wang Y, Zhao W, Li M, Wang Q, et al. Selection of suitable reference genes for quantitative real-time PCR in Sapium sebiferum. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:637. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li MY, Song X, Wang F, Xiong AS. Suitable reference genes for accurate gene expression analysis in parsley (Petroselinum crispum) for abiotic stresses and hormone stimuli. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:1481. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu L, Xu H, Cao Y, Yang P, Feng Y, Tang Y, Yuan S, Ming J. Validation of reference genes for quantitative real-time PCR during bicolor tepal development in asiatic hybrid lilies (Lilium spp.) Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:669. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Niu X, Chen M, Huang X, Chen H, Tao A, Xu J, Qi J. Reference gene selection for qRT-PCR normalization analysis in kenaf (Hibiscus cannabinus L.) under abiotic stress and hormonal stimuli. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:771. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.An H, Zhu Q, Pei W, Fan J, Liang Y, Cui Y, Lv N, Wang W. Whole-transcriptome selection and evaluation of internal reference genes for expression analysis in protocorm development of Dendrobium officinale Kimura et Migo. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(11):e0163478. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0163478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takahashi K, Kawaguchi S, Nishimura K, Kubota K, Tanabe Y. Studies on constituents of medicinal plants. XIII. Constituents of the pericarps of the capsules of Euscaphis japonica Pax. Chem Pharm Bull. 1974;22(3):650–653. doi: 10.1248/cpb.22.650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cheng JJ, Zhang LJ, Cheng HL, Chiou CT, Lee IJ, Kuo YH. Cytotoxic hexacyclic triterpene acids from Euscaphis japonica. J Nat Prod. 2010;73(10):1655–1658. doi: 10.1021/np1003593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li YC, Tian K, Sun LJ, Long H, Li LJ, Wu ZZ. A new hexacyclic triterpene acid from the roots of Euscaphis japonica and its inhibitory activity on triglyceride accumulation. Fitoterapia. 2016;109:261–265. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2016.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee MK, Lee KY, Jeon HY, Sung SH, Kim YC. Antifibrotic activity of triterpenoids from the aerial parts of Euscaphis japonica on hepatic stellate cells. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem. 2009;24(6):1276–1279. doi: 10.3109/14756360902829709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maeda H, Matsuo Y, Tanaka T, Kouno I. Euscaphinin, a new ellagitannin dimer from Euscaphis japonica (THUNB.) KANITZ. Chem Pharm Bull. 2009;57(4):421–423. doi: 10.1248/cpb.57.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee MK, Jeon HY, Lee KY, Kim SH, Ma CJ, Sung SH, Lee HS, Park MJ, Kim YC. Inhibitory constituents of Euscaphis japonica on lipopolysaccharide-induced nitric oxide production in BV2 microglia. Planta Med. 2007;73(8):782–786. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-981551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takeda Y, Okada Y, Masuda T, Hirata E, Shinzato T, Takushi A, Yu Q, Otsuka H. New megastigmane and tetraketide from the leaves of Euscaphis japonica. Chem Pharm Bull. 2000;48(5):752–754. doi: 10.1248/cpb.48.752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takeda Y, Okada Y, Masuda T, Hirata E, Takushi A, Otsuka H. Euscapholide and its glucoside from leaves of Euscaphis japonica. Phytochemistry. 1998;49(8):2565–2568. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(98)00193-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guo Y, Chen JX, Yang S, Fu XP, Zhang Z, Chen KH, Huang Y, Li Y, Xie Y, Mao YM. Selection of reliable reference genes for gene expression study in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2010;31(11):1487–1494. doi: 10.1038/aps.2010.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Han X, Lu M, Chen Y, Zhan Z, Cui Q, Wang Y. Selection of reliable reference genes for gene expression studies using real-time PCR in tung tree during seed development. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(8):e43084. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vanholme R, Demedts B, Morreel K, Ralph J, Boerjan W. Lignin biosynthesis and structure. Plant Physiol. 2010;153(3):895–905. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.155119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vanholme R, Morreel K, Darrah C, Oyarce P, Grabber JH, Ralph J, Boerjan W. Metabolic engineering of novel lignin in biomass crops. New Phytol. 2012;196(4):978–1000. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2012.04337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Velasco R, Zharkikh A, Affourtit J, Dhingra A, Cestaro A, Kalyanaraman A, Fontana P, Bhatnagar SK, Troggio M, Pruss D, et al. The genome of the domesticated apple (Malus × domestica Borkh.) Nat Genet. 2010;42(10):833–839. doi: 10.1038/ng.654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Parkin IA, Koh C, Tang H, Robinson SJ, Kagale S, Clarke WE, Town CD, Nixon J, Krishnakumar V, Bidwell SL, et al. Transcriptome and methylome profiling reveals relics of genome dominance in the mesopolyploid Brassica oleracea. Genome Biol. 2014;15(6):R77. doi: 10.1186/gb-2014-15-6-r77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chapman JA, Mascher M, Buluc A, Barry K, Georganas E, Session A, Strnadova V, Jenkins J, Sehgal S, Oliker L, et al. A whole-genome shotgun approach for assembling and anchoring the hexaploid bread wheat genome. Genome Biol. 2015;16:26. doi: 10.1186/s13059-015-0582-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Harper AL, Trick M, He Z, Clissold L, Fellgett A, Griffiths S, Bancroft I. Genome distribution of differential homoeologue contributions to leaf gene expression in bread wheat. Plant Biotechnol J. 2016;14(5):1207–1214. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guan R, Zhao Y, Zhang H, Fan G, Liu X, Zhou W, Shi C, Wang J, Liu W, Liang X, et al. Draft genome of the living fossil Ginkgo biloba. GigaScience. 2016;5(1):49. doi: 10.1186/s13742-016-0154-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lin Y, Min J, Lai R, Wu Z, Chen Y, Yu L, Cheng C, Jin Y, Tian Q, Liu Q, et al. Genome-wide sequencing of longan (Dimocarpus longan Lour.) provides insights into molecular basis of its polyphenol-rich characteristics. GigaScience. 2017;6(5):1–14. doi: 10.1093/gigascience/gix023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhan X, Yang L, Wang D, Zhu JK, Lang Z. De novo assembly and analysis of the transcriptome of Ocimum americanum var. pilosum under cold stress. BMC Genom. 2016;17:209. doi: 10.1186/s12864-016-2507-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Evangelistella C, Valentini A, Ludovisi R, Firrincieli A, Fabbrini F, Scalabrin S, Cattonaro F, Morgante M, Mugnozza GS, Keurentjes JJB, et al. De novo assembly, functional annotation, and analysis of the giant reed (Arundo donax L.) leaf transcriptome provide tools for the development of a biofuel feedstock. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2017;10:138. doi: 10.1186/s13068-017-0828-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Abdeen A, Schnell J, Miki B. Transcriptome analysis reveals absence of unintended effects in drought-tolerant transgenic plants overexpressing the transcription factor ABF3. BMC Genom. 2010;11:69. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Galla G, Vogel H, Sharbel TF, Barcaccia G. De novo sequencing of the Hypericum perforatum L. flower transcriptome to identify potential genes that are related to plant reproduction sensu lato. BMC Genom. 2015;16:254. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1439-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sunkar R, Zhou X, Zheng Y, Zhang W, Zhu JK. Identification of novel and candidate miRNAs in rice by high throughput sequencing. BMC Plant Biol. 2008;8:25. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-8-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nobuta K, Lu C, Shrivastava R, Pillay M, De Paoli E, Accerbi M, Arteaga-Vazquez M, Sidorenko L, Jeong DH, Yen Y, et al. Distinct size distribution of endogeneous siRNAs in maize: evidence from deep sequencing in the mop1-1 mutant. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(39):14958–14963. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808066105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu TT, Zhu D, Chen W, Deng W, He H, He G, Bai B, Qi Y, Chen R, Deng XW. A global identification and analysis of small nucleolar RNAs and possible intermediate-sized non-coding RNAs in Oryza sativa. Mol Plant. 2013;6(3):830–846. doi: 10.1093/mp/sss087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhuang H, Fu Y, He W, Wang L, Wei Y. Selection of appropriate reference genes for quantitative real-time PCR in Oxytropis ochrocephala Bunge using transcriptome datasets under abiotic stress treatments. In: Frontiers in plant science. vol. 6, 2015/07/16 edn; 2015:475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Wang H, Zhang X, Liu Q, Liu X, Ding S. Selection and evaluation of new reference genes for RT-qPCR analysis in Epinephelus akaara based on transcriptome data. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(2):e0171646. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0171646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Demidenko NV, Logacheva MD, Penin AA. Selection and validation of reference genes for quantitative real-time PCR in buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum) based on transcriptome sequence data. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(5):e19434. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ma R, Xu S, Zhao Y, Xia B, Wang R. Selection and validation of appropriate reference genes for quantitative real-time PCR analysis of gene expression in Lycoris aurea. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:536. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ma S, Niu H, Liu C, Zhang J, Hou C, Wang D. Expression stabilities of candidate reference genes for RT-qPCR under different stress conditions in soybean. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(10):e75271. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Monteiro F, Sebastiana M, Pais MS, Figueiredo A. Reference gene selection and validation for the early responses to downy mildew infection in susceptible and resistant Vitis vinifera cultivars. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(9):e72998. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Guo J, Ling H, Wu Q, Xu L, Que Y. The choice of reference genes for assessing gene expression in sugarcane under salinity and drought stresses. Sci Rep. 2014;4:7042. doi: 10.1038/srep07042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tian C, Jiang Q, Wang F, Wang GL, Xu ZS, Xiong AS. Selection of suitable reference genes for qPCR normalization under abiotic stresses and hormone stimuli in carrot leaves. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(2):e0117569. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cao J, Wang L, Lan H. Validation of reference genes for quantitative RT-PCR normalization in Suaeda aralocaspica, an annual halophyte with heteromorphism and C4 pathway without Kranz anatomy. PeerJ. 2016;4:e1697. doi: 10.7717/peerj.1697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wan D, Wan Y, Yang Q, Zou B, Ren W, Ding Y, Wang Z, Wang R, Wang K, Hou X. Selection of reference genes for qRT-PCR analysis of gene expression in Stipa grandis during environmental stresses. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(1):e0169465. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0169465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Warzybok A, Migocka M. Reliable reference genes for normalization of gene expression in cucumber grown under different nitrogen nutrition. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(9):e72887. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ray DL, Johnson JC. Validation of reference genes for gene expression analysis in olive (Olea europaea) mesocarp tissue by quantitative real-time RT-PCR. BMC Res Notes. 2014;7:304. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-7-304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gimeno J, Eattock N, Van Deynze A, Blumwald E. Selection and validation of reference genes for gene expression analysis in switchgrass (Panicum virgatum) using quantitative real-time RT-PCR. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(3):e91474. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Qi S, Yang L, Wen X, Hong Y, Song X, Zhang M, Dai S. Reference gene selection for RT-qPCR analysis of flower development in Chrysanthemum morifolium and Chrysanthemum lavandulifolium. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:287. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhao Y, Luo J, Xu S, Wang W, Liu T, Han C, Chen Y, Kong L. Selection of reference genes for gene expression normalization in Peucedanum praeruptorum Dunn under abiotic stresses, hormone treatments and different tissues. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(3):e0152356. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lan T, Yang ZL, Yang X, Liu YJ, Wang XR, Zeng QY. Extensive functional diversification of the Populus glutathione S-transferase supergene family. Plant Cell. 2009;21(12):3749–3766. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.070219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lenart P, Bacher CP, Daigle N, Hand AR, Eils R, Terasaki M, Ellenberg J. A contractile nuclear actin network drives chromosome congression in oocytes. Nature. 2005;436(7052):812–818. doi: 10.1038/nature03810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Insall RH, Machesky LM. Actin dynamics at the leading edge: from simple machinery to complex networks. Dev Cell. 2009;17(3):310–322. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kuure S, Cebrian C, Machingo Q, Lu BC, Chi X, Hyink D, D’Agati V, Gurniak C, Witke W, Costantini F. Actin depolymerizing factors cofilin1 and destrin are required for ureteric bud branching morphogenesis. PLoS Genet. 2010;6(10):e1001176. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chao J, Yang S, Chen Y, Tian WM. Evaluation of reference genes for quantitative real-time PCR analysis of the gene expression in laticifers on the basis of latex flow in rubber tree (Hevea brasiliensis Muell. Arg.) Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:1149. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Li W, Zhang L, Zhang Y, Wang G, Song D, Zhang Y. Selection and validation of appropriate reference genes for quantitative real-time PCR normalization in staminate and perfect flowers of andromonoecious Taihangia rupestris. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:729. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. Sequences of 12 candidate genes and 1 validation gene.

Additional file 2. Alignment and phylogenetic tree of 12 candidate genes and 1 validation gene.

Additional file 3. Melting curves for the 12 candidate reference genes.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets supporting the conclusions and description of a complete protocol are included within the article.