Abstract

Immigration leads to strong public and political debates in Europe and the Western world more generally. In some of these debates, migrants are described as either having little choice but to migrate (involuntary migrants) or migrating out of their own free choice (voluntary migrants). In two experimental studies among national samples of native Dutch respondents, we examined whether support for the accommodation of newcomers differs for voluntary and involuntary migrants and whether this depends on the relative importance of humanitarian considerations and host society considerations. The findings demonstrate that for people who find the topic of immigration personally important, involuntary, compared to voluntary, migration leads to stronger societal considerations which, in turn, is associated with weaker support for the accommodation of migrants. Additionally, humanitarian considerations are associated with stronger support but especially for participants who do not find the topic of immigration very important.

Keywords: migrants, (in)voluntariness, morality, societal interests, public attitudes

“The moral duty—certainly for a politician—is dual. It concerns refugees but it also concerns the society, the peace in one’s society, justice for its citizens. There is not a morality which says that refugees have priority.”

Sybrand Buma, political leader of the Dutch political party “Christian Democrats,” in TV program Buitenhof, October 18, 2015.

Geopolitical events have led to the so-called refugee crisis and the steady increase in immigrants. This raises many difficult questions for western host societies. As illustrated by the quote, it involves, among other things, finding a balance between humanitarian considerations and societal concerns. Support for the accommodation of newcomers is more likely when humanitarian concerns are considered and less likely when the emphasis is on concerns about societal fairness and cohesion. One important factor that might affect the relevance of these contrasting considerations is the way in which newcomers are defined. The term “migrants” comprises a heterogeneous category in public and political debates (Moses, 2006) which offers room for construing different understandings of who these newcomers are and why they are “here” (Blinder, 2015; Blinder & Allen, 2016). Some politicians and mass media emphasize the difficult fate of “real refugees” or “involuntary migrants” and the need to offer support and help to these newcomers, whereas other politicians and media claim that the majority of newcomers are “bogus refugees” or “voluntary migrants” (Lynn & Lea, 2003; Verkuyten, 2014). The relatively strong debate about the appropriate label indicates that much is at stake.

The labels “voluntary” and “involuntary” are used in different ways and in different contexts with different implications. When the U.S. Housing and Urban Development Secretary Ben Carson referred to slaves brought from Africa as “immigrants” (March 2017), critics lambasted him for this and he specified his remark to slaves being “involuntary immigrants.” The distinction also features in social scientific analyses of the situation of “voluntary” and “involuntary” migrant populations (e.g., Ogbu, 1993), and in his influential book on Multicultural Citizenship, the political philosopher Kymlicka (1995) makes a distinction between voluntary and involuntary minority groups. He argues that cultural recognition and rights are reasonable demands for indigenous groups or groups that have been historically wronged (e.g., descendants of African slaves), but that immigrants would have waived their group-specific demands and rights by voluntarily leaving their country of origin.

Self-determination implies a personal responsibility for one’s situation. Responsibilities are defined differently when there is little choice and actions are determined by others or circumstances (Weiner, 1995). Hence, defining or challenging a particular situation as self-determined has important consequences, such as in welfare debates about “deserving” and “undeserving” citizens, in accounting for people’s health and illness, in explaining unemployment and poverty, and in relation to migrants. Appelbaum (2002) found that migrant groups which were perceived to have higher responsibility for their need of assistance were considered less deserving of support and aid. In another study, it was found that the endorsement of cultural rights for immigrants depends on whether immigrants are described as being themselves responsible for their situation or not (Verkuyten, 2004). And experimental research has found a similar effect of perceived (in)voluntariness on the support of migrants’ cultural rights not only of immigrants but also of emigrants (Gieling, Thijs, & Verkuyten, 2011). This indicates that defining a particular action as voluntary (self-determined) or involuntary (others determined) has more general consequences for people’s attitudes toward migration.

In general, a profile of newcomers which matches that of the involuntary migrant (e.g., “real refugee”) is typically considered as deserving humanitarian concern, whereas those labeled as voluntary migrants (e.g., “bogus refugees”) are presented as a realistic and symbolic threat to the country’s legitimate self-interests and, as such, an understandable target of feelings of anger and resentment (Augoustinos & Quinn, 2003; Maio, Bell, & Esses, 1996). People tend to react in an irritated and hostile manner to the demands of others when they perceive them as personally responsible for their plight (e.g., Feather, 1999; Schmidt & Weiner, 1988). In that case, the focus is less on the other suffering and more on the own costs in providing help and support (Montada & Schneider, 1989; Verkuyten, 2004).

Humanitarian considerations and the related feelings of empathy are based on identification with the unfortunate situation of others and this is more likely when the neediness of people is perceived to be beyond their control (e.g., Batson, 1998; Betancourt, 1990; Castano, 2012). These concerns and feelings provide a psychological basis of willingness to help and support ameliorative policies and social programs (see Weiner, 1995). In three studies conducted in the United States, it was found that individual differences in humanitarian concern were associated with support for immigration (Newman, Hartman, Lown, & Feldman, 2015), and the same was found in Australia (Nickelson & Louis, 2008) and in Turkey (Yitmen & Verkuyten, 2017).

In the current study, we examined whether the two representations of migrants (voluntary or involuntary) differently affect the relevance of humanitarian values and the value of host society interests which, in turn, might underpin the support to accommodate migrants. The question of accommodating migrants tends to involve a balancing of competing principles and values (see quote above this article). On the one hand, there are humanitarian considerations, and on the other hand, there is the principle of societal costs and social cohesion. According to Schwartz (1992, 1996), individuals can simultaneously consider value types that are opposite to each other such as between values that express humanitarianism (universalism) and value types that express a concern with harmony and stability of society (security). According to moral foundations theory (Graham et al., 2013), the moral domain is broader than empathy and care for those in need but also involves loyalty and support for the integrity of the in-group. Similarly, unity as the motive to support the integrity of the in-group by avoiding or eliminating threats is considered a moral motive in the relational models theory (Rai & Fiske, 2011). According to these theories, both humanitarian concerns and concerns about societal unity can be construed and perceived as moral considerations

We examined the relevance of humanitarian considerations and of host societal interests for the attitude toward the accommodation of migrants. Specifically, we expected that voluntary, versus involuntary, migration elicits more strongly societal considerations and less strongly humanitarian ones and therefore is associated with a less positive attitude toward the accommodation of migrants. In testing this expectation, we also considered attitude importance—as a feature of attitude strength—as a possible moderator of the expected relations (Howe & Krosnick, 2017). It is likely that the expected associations exist for people who consider the topic of immigration personally important. They are involved in the topic and will feel that there is something at stake. In contrast, people who are not much interested in immigration can be expected to be influenced less by the (in)voluntariness of immigration and to be less concerned about the related humanitarian and societal considerations.

We tested the expectations in two Internet studies with survey embedded experiments among the native Dutch. The first study used data from a relatively large national sample and the second one was conducted among a smaller sample. The Netherlands is one of the European countries that since the beginning of 2015 has received relatively many migrants, including a relatively large number of refugees. This influx has led to quite a strong and polarized societal debate whereby some sections of the population argue in favor of accepting and supporting these newcomers, whereas other sections of the public have a rejecting attitude and favor border closure.

Study 1

Data and Method

Sample

A probability sample of Dutch majority members (18 years and older) was drawn by GfK Consult, a bureau specialized in collecting national data. In February 2017, participants received an online questionnaire about Dutch society and cultural diversity. The original sample consisted of 867 respondents. The questionnaire contained several survey embedded experiments and two of the eight versions of the questionnaire contained a separate section with the experiment on voluntary–involuntary migrants that is central in the current paper.1 The respondents in this subsample (N = 217) came from all regions of the Netherlands and were between 18 and 97 years (17.5% 19–29 years, 11.1% 30–39 years, 19.4% 40–49 years, 24.9% 50–64 years, and 27.2% 65–98 years), with 53.5% females and 46.5% males. Post hoc power analysis using G*Power 3.1 revealed that with this sample size and the mediation model with one-tailed probabilities of .05, there is an 85% power.

Experimental Procedure and Measurements

Respondents were randomly assigned to one of two conditions. In the involuntary condition (N = 109), the introduction was “Public opinion research indicates that many Dutch people have their own opinion about the arrival of migrants who have no choice and are forced to leave their country.” In the voluntary condition (N = 108), it was stated, “Public opinion research indicates that many Dutch people have their own opinion about migrants who completely out of their own free will come to the Netherlands.” Subsequently and following Skitka, Bauman, and Sargis (2005), respondents were presented with a single-item measure (5-point scale; not at all to very much) that directly asked to what extent their humanitarian considerations form the basis of their personal views (My own moral principles and humanitarian convictions determine how I think about this topic). Similarly, the extent to which their views are based on host societal considerations was also assessed with a single item (My idea about the financial and societal costs for our society determines how I think about this topic). Respondents indicated that their views about migrants were more strongly based on moral consideration (M = 3.33, SD = 0.99) than societal considerations (M = 2.64, SD = 1.11), t(217) = 8.04, p < .001, d = .55, and both considerations were not very strongly associated (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Mean Scores, Standard Deviations, and Intercorrelations for the Different Measures in Study 1.

| Measured constructs | M | SD | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Accommodation of migrants | 3.95 | (0.55) | −.01 | .03 | −.04 |

| 2. Humanitarian considerations | 3.33 | (0.99) | — | .28** | .16* |

| 3. Societal considerations | 2.64 | (1.11) | — | .37** | |

| 4. Attitude importance | 3.20 | (0.95) | — |

*p < .01. **p < .001.

Attitude importance was measured with the question adapted from previous research (Skitka, Bauman, & Sargis, 2005), “How important is the topic of immigration for you personally” (5-point scale, from not at all important to very important).

Accommodation of migrants

Four items (7-point scales; completely not agree to fully agree) were used to measure support for the accommodation of migrants: “On questions of immigration one should focus predominantly on the opportunities for migrants,” “I am in favor of migrants coming to the Netherlands,” “The Netherlands should close its borders for migrants as much as possible (reverse),” and “Migration policies should be much less restrictive.” The 4 items were averaged into a single score (α = .75) and a higher score indicates higher support.

Results

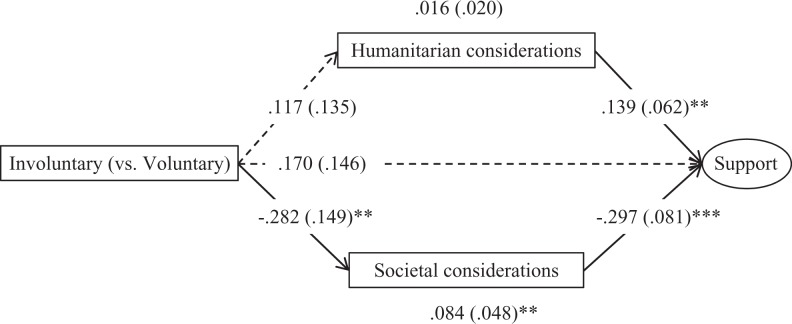

Table 1 shows the mean scores and intercorrelations between the different measures. We first examined whether attitude importance differed between the voluntary (M = 3.26, SD = 0.98) and involuntary (M = 3.15, SD = 0.91) experimental conditions and this was not the case, t(215) = .87, p = .382, 95% confidence interval (CI) [−.14, .37], d = .12. Structural equation modeling in Mplus was conducted to predict support for the accommodation of immigrants. In a first model, we tested the mediating roles of humanitarian and societal considerations in the effect of the experimental manipulation on support (Figure 1). This analysis yielded a model with a reasonable fit, χ2(12, N = 217) = 30.678, p = .0022, comparative fit index (CFI) = .872, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = .085, 90% CI [.048, .122], Akaike information criterion (AIC) = 4,247.474. Compared to the voluntary condition, involuntary migration elicited stronger societal considerations (B = −.282, SE = .149, p = .029), whereas there was no difference in humanitarian considerations (B = .117, SE = .135, p = .192). In addition, stronger societal considerations was associated with lower support (B = −.297, SE = .068, p < .001) and stronger humanitarian considerations with higher support (B = .139, SE = .062, p = .013). Furthermore, the indirect effect of the experimental condition on support via societal considerations was positive and significant (B = .084, SE = .048, p = .040), whereas the indirect effect via humanitarian concerns was not significant (B = .016, SE = .020, p = .209).

Figure 1.

Humanitarian and societal considerations as separate mediators between the (in)voluntariness of migration and support for the accommodation of immigrants, Study 1. Unstandardized coefficients, standard errors within parentheses. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Moderated Mediation Model

To test the possibility that the mediation process depends on individual attitude importance, we first estimated a model in which the continuous measure of attitude importance moderated the four different paths. This model showed that attitude importance significantly moderated the paths from the experimental condition to humanitarian considerations (p = .029), and to societal considerations (p = .020) and also the path from societal considerations to support (p < .001).

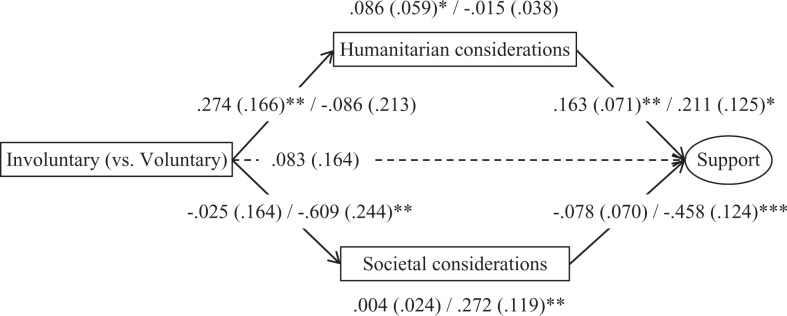

In further examining these interactions, we estimated a multigroup structural equation model by splitting the sample in low (≤3) and high attitude importance (>3). The fit indices indicate that the fit was acceptable and better than the previous model, χ2(27, N = 217) = 36.617, p = .1024, CFI = .926, RMSEA = .074 90% CI [.000, .100], AIC = 4,175.044. Figure 2 shows that when attitude importance was high, involuntary (compared to voluntary) migration elicited more strongly societal considerations (B = −.609, SE = .244, p = .007) than when attitude importance was low (B = −.025, SE = .164, p = .440). In addition, when attitude importance was high, stronger societal considerations were significantly associated with lower support (B = −.458, SE = .124, p < .001); whereas societal considerations were not significantly associated with support when attitude importance was low (B = −.080, SE = .069, p = .124). Furthermore, when attitude importance was high, involuntary migration was indirectly and significantly associated with support through societal considerations (B = .285, SE = .138, p = .019), but when attitude importance was low, the indirect effect was not significant (B = .002, SE = .013, p = .441). These two indirect effects of the experimental condition through societal considerations were significantly different, Wald(1) = 4.171, p = .041.

Figure 2.

The moderating role of attitude importance: multigroup structural equation model (low/high attitude strength; N = 133/84) in Study 1. Unstandardized coefficients and standard errors within parentheses. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Involuntary compared to voluntary migration also elicited stronger humanitarian considerations for those participants who did not find the topic of immigration very important (low attitude importance; B = .274, SE = .166, p = .047), whereas this was not the case for participants who did find the topic important (B = −.086, SE = .213, p = .383). When attitude importance was low, the indirect effect through humanitarian considerations was marginally significant (B = .045, SE = .033, p = .090), and when it was high it was not significant (B = −.018, SE = .046, p = .347). The difference in indirect effects was not significant, Wald(1) = 1.207, p = .272.

Study 2

Study 2 tried to address two limitations of the first study. One limitation relates to the possible confound in the experimental manipulation used in Study 1. In this study, the framing in the two conditions did not only differ in the voluntary versus involuntary nature of migrant’s arrival but also in the explicit reference that was made toward the country of origin (involuntary condition) and the Netherlands as the country of arrival (voluntary condition). Although not very likely, it is possible that the differences between the two conditions are in part due to the distinction between country of origin and country of arrival. Therefore, in Study 2, we more clearly distinguished between both experimental conditions in terms of voluntary versus involuntary migration. The second limitation is that due to the constraints of the survey with a representative sample, the humanitarian and societal considerations were each measured with 1 item only. In Study 2, we used 2 items to measure each of the two constructs.

Data and Method

Sample

A probability sample of Dutch majority members (18 years and older) was drawn by ThesisTools, a bureau specialized in collecting national data. In June and July 2017, participants received an online questionnaire about Dutch society and cultural diversity. The respondents in the sample (N = 321) came from all regions of the Netherlands and were between 18 and 84 years (M = 49.94), with 53.9% females and 46.1% males. Post hoc power analysis using G*Power 3.1 revealed that with this sample size and the mediation model with one-tailed probabilities of .05, there is a 97% power.

Experimental Procedure and Measurements

Respondents were randomly assigned to one of two conditions. In the involuntary condition (N = 158), the introduction was “Public opinion research indicates that many Dutch people have their own opinion about the arrival of migrants who had no choice and were forced to leave their country.” In the voluntary condition (N = 163), it was stated, “Public opinion research indicates that many Dutch people have their own opinion about the arrival of migrants who completely out of their own free will have left their country.”

For assessing to what extent participants’ moral considerations formed the basis of their personal views, we used 2 items with 5-point scales (“My opinion on this topic is based on my moral convictions” and “My humanitarian principles determine how I think about this topic”; r = .77, p < .001, 95% CI [.72, .81]). Similarly, the extent to which participants’ views were based on host societal considerations was assessed with 2 items on 5-point scales (“My idea about the financial costs for our society determines how I think about this topic” and “My idea about the societal implications for our society determines how I think about this topic”; r = .61, p < .001, 95% CI [.54, .68]).

Attitude importance was measured with the same question that was used in Study 1 and the mean score was similar (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Mean Scores, Standard Deviations and Intercorrelations for the Different Measures in Study 2.

| Measured constructs | M | SD | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Accommodation of migrants | 4.45 | (0.70) | −.05 | .35*** | .11* |

| 2. Humanitarian considerations | 3.83 | (0.92) | — | .01 | .30*** |

| 3. Societal considerations | 2.84 | (1.05) | — | .25*** | |

| 4. Attitude importance | 3.56 | (0.85) | — |

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Support for the accommodation of migrants

The same 4 items used in Study 1 were used to measure support for the accommodation of migrants (α = .86).

Results

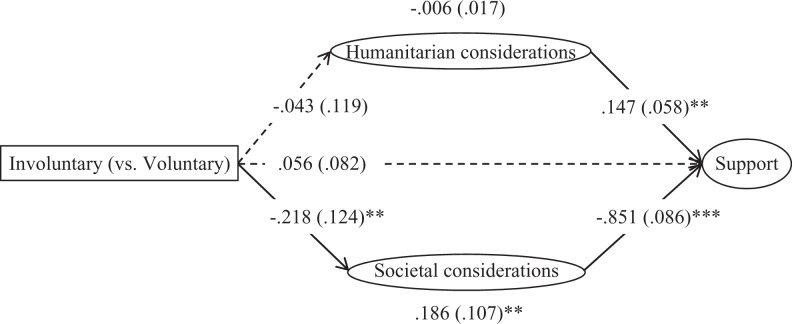

The descriptive findings are shown in Table 2. We first examined whether attitude importance differed between the voluntary (M = 3.61, SD = 0.91) and involuntary (M = 3.51, SD = 0.79) conditions and this was again not the case, t(319) = .98, p = .329, 95% CI [−.09, .28], d = .11. A structural equation model with latent constructs for the different measures was estimated (Figure 3). This model fits the data well, χ2(22, N = 321) = 36.75, p = .025, CFI = .981, RMSEA = .046, 90% CI [.016, .071], AIC = 7,561.876, and the findings are very similar to Study 1. Compared to the voluntary condition, involuntary migration did not elicit stronger humanitarian considerations (B = −.043, SE = .119, p = .359) but did lead to stronger societal considerations (B = −.851, SE = .086, p < .001). Societal considerations were negatively associated with the support for the accommodation of immigrants (B = −.851, SE = .086, p < .001), whereas humanitarian considerations were positively associated with support for the accommodation of immigrants (B = .147, SE = .058, p = .006). Furthermore, the indirect effect of the experimental condition on support through societal considerations was positive (B = .186, SE = .107, p = .042). The indirect effect through humanitarian considerations was, again, not significant (B = −.006, SE = .017, p = .355).

Figure 3.

Humanitarian and societal considerations as separate mediators between the (in)voluntariness of migration and support for the accommodation of immigrants, Study 2. Unstandardized coefficients, standard errors within parentheses. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Moderated Mediation Model

We followed the same procedure as in Study 1 to test the moderated mediation model. The model with attitude importance as a continuous variable showed that the paths from experimental condition to humanitarian considerations and from societal considerations to accommodation support differed by attitude importance (B = −.218, SE = .119, p = .033; B = −.140, SE = .050, p = .003, respectively).

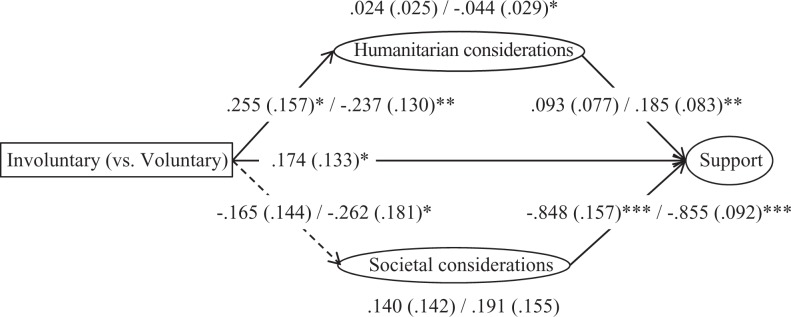

To further investigate these interactions, we again estimated a multigroup model and the findings are shown in Figure 4. When attitude importance was low, involuntary compared to voluntary migration elicited stronger humanitarian considerations (B = .255, SE = .157, p = .053), and when attitude importance was high involuntary migration elicited weaker humanitarian considerations (B = −.237, SE = .131, p = .035). The indirect effect of the experimental condition on support through humanitarian considerations was positive when attitude importance was low (B = .024, SE = .025, p = .167), and negative when it was high (B = −.044, SE = .029, p = .066). The difference in these indirect effects was significant, Wald(1) = 3.155, p = .076. This pattern of findings is similar to Study 1.

Figure 4.

The moderating role of attitude importance: multigroup structural equation model (low/high attitude strength; N = 145/176) in Study 2. Unstandardized coefficients and standard errors within parentheses. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Furthermore and also similar to Study 1, for participants who did not find the topic of immigration very important, the experimental condition did elicit a smaller difference in societal considerations (B = −.165, SE = .144, p = .125) than for those participants who did find the topic important (B = −.224, SE = .181, p = .108). The moderation analysis with the continuous measure for attitude importance also showed a significant interaction effect between societal considerations and support. However, the multiple-group analysis with its reduction in variance (Cohen, 1983) did not indicate a clear difference in associations between the group with low and high attitude importance (B = −.848, SE = .157, p < .001; B = −.855, SE = .095, p < .001, respectively). However, further analyses (different group splitting) indicated that, similar to Study 1, the negative association was stronger for high compared to low attitude importance. Finally, the indirect effect of the experimental condition through societal considerations was positive when attitude importance was low (B = .140, SE = .126, s = .132), and also positive when importance was high (B = .191, SE = .155, p = .109).

Discussion

Using two studies and an experimental design, we examined whether the way in which the reasons for migration are described has implications for majority members’ support to accommodate migrants. Previous research on attitudes toward immigrant has focused, for example, on the importance of the distinction between culturally similar or more dissimilar migrant groups (Ford, 2011) and between highly skilled and low-skilled immigrants (Hainmueller & Hangartner, 2013; Hainmueller & Hiscox, 2010). We went beyond this research by examining the distinction between voluntary and involuntary migrants which features (explicitly and implicitly) in societal and political debates (Verkuyten, 2014). Furthermore, we focused on the importance of humanitarian considerations and of host society considerations for the support to accommodate migrants.

The pattern of findings in both studies is very similar. The findings demonstrated that migrants who were defined as having chosen themselves to migrate triggered more concerns about the impact on the host society than migrants who were defined as being forced to leave their home country. This was especially the case for participants who found the topic of immigration personally important (Study 1). For these participants, the way migration was construed mattered for how concerned they were about host societal implications which, in turn, was related to their lower support to accommodate migrants.

Stronger endorsement of humanitarian considerations was associated with higher accommodation support. Further, migration construal mattered for the degree to which humanitarian considerations were elicited, depending on attitude importance. Involuntary compared to voluntary migration triggered stronger humanitarian considerations for participants who did not find the topic of immigration very important (Studies 1 and 2). And among participants who did find the topic personally important, involuntary migration elicited weaker humanitarian considerations (Study 2). Taken together, the pattern of findings in both studies indicates that for people who find immigration a personally important topic, the definition of migration as being involuntary (compared to voluntary) makes societal as well as humanitarian considerations less relevant. These people tend to focus less on the impact on the host society that migrants have when they are being forced to leave their country. Yet the findings suggest that such a definition might also backfire by reducing humanitarian considerations. In contrast, for people who do not consider the topic of migration personally important, involuntary (compared to voluntary) migration made humanitarian considerations more relevant and did not matter for societal considerations. These people seem to respond to the implied humanitarian responsibility to help those who are in need beyond their control.

The findings demonstrate that the perceived (in)voluntariness of migration has an impact on the support for accommodating migrants. It differently defines migrants’ own responsibility for leaving their home country and this matters for the attitude that the public has toward newcomers. Other experimental research has found a similar effect of perceived (in)voluntariness on migrants’ cultural rights (Gieling et al., 2011; Verkuyten, 2004) not only for immigrants but also for emigrants (Gieling et al., 2011, Study 2). This indicates that defining a particular action as voluntary (self-determined) or involuntary (others determined) has more general consequences for people’s attitudes toward migration (Applebaum, 2002). The current research goes beyond these previous studies by considering the roles of humanitarian and societal considerations and by showing that the effect of perceived voluntariness depends on whether people find the topic of migration personally important.

Future social psychological studies could examine the emotional reactions that might underlie the associations found. The plight of migrants can elicit various emotional feelings that influence the support for policies aimed at accommodating migrants. Anger about the neediness of others is a common emotional reaction when people themselves are considered responsible for their own plight (e.g., Schmidt & Weiner, 1988), whereas empathy and sympathy are more likely when their neediness is perceived to be beyond their control (e.g., Betancourt, 1990; Castano, 2012). Hence, the perception that most migrants have a “personal choice” or rather a “lack of choice” provides different frameworks for supporting policies for newcomers that might elicit different emotions (Verkuyten, 2004). Future studies could also examine these processes further by including, for example, direct measures of perceived responsibility of migrants, feelings of threat, and also deservingness which have been identified as critical factors in support for affirmative action policies (e.g., Appelbaum, 2001, 2002; Reyna, Henry, Korfmacher, & Tucker, 2005).

In conclusion, with two studies and national samples, the present experimental research demonstrates for the first time that the public’s support for the accommodation of migrants depends on the perceived (in)voluntariness of migration that triggers different levels of humanitarian and host societal concerns. This indicates that the ways in which issues of migration are framed by the mass media and politicians can play an important role in the public support (Blinder, 2015; Herda, 2015; Héricourt & Spielvogel, 2014). Distinctions made between involuntary and voluntary migrants and between “real refugees” and “fortune seekers” can have important implications for how the public defines responsibilities and therefore how much support immigrants are considered to deserve or are entitled to. However, there are also important individual differences that should be taken into account. Some people go along with a particular representation of migrants that is offered in the media or by politicians, while other people resist and oppose it. The current research demonstrates that the importance people personally attach to the topic of immigration is a relevant factor to consider. Future research could examine the role of other individual difference variables, such as national identification and social dominance orientation.

As is common in national surveys, several other researchers had included other measures that are not directly relevant for and not meant to consider in the current study (e.g., on social trust, deprovincialization, contacts with ethnic minority groups, indispensability, islamophobia, autochthony, and partisanship). In a prior, but separate and unrelated, part of the questionnaire, participants were also presented with two other experiments. Therefore, we tested for carryover effects. In a preliminary analysis, the two other experiments (two conditions each) were used as dummy variables in the analyses of the responses to the (in)voluntariness experiment. These factors were not (either individually or in combination) related to the outcomes of the current experiment (ps > .20), indicating that there are no problematic carryover effects.

Author Biographies

Maykel Verkuyten is a professor in Interdisciplinary Sociale Science at Utrecht University and the academic director of the European Research Centre on Migration and Ethnic Relations (ERCOMER) at Utecht University.

Hadi Ghazi Altabatabaei is a PhD student at the University in Budapest.

Wybren Nooitgedagt is a PhD student at Utrecht University.

Handling Editor: Kate Ratliff

Note

In this study, no other questions were asked or prior experimental manipulations used.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Appelbaum L. D. (2002). Who deserves help? Students’ opinions about the deservingness of different groups living in Germany to receive aid. Social Justice Research, 15, 201–225. [Google Scholar]

- Augoustinos M., Quinn C. (2003). Social categorization and attitudinal evaluations: Illegal immigrants, refugees or asylum seekers? New Review of Social Psychology, 2, 29–37. [Google Scholar]

- Batson C. D. (1998). Altruism and prosocial behavior In Gilbert D. T., Fiske S. T., Lindzey G. (Eds.), The handbook of social psychology (pp. 282–316). Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt H. (1990). An attribution-empathy model of helping behavior: Behavioral intentions and judgments of help-giving. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 16, 573–591. [Google Scholar]

- Blinder S. (2015). Imagined integration: The impact of different meanings of ‘immigrants’ in public opinion and policy debates in Britain. Political Studies, 63, 80–100. [Google Scholar]

- Blinder S., Allen W. L. (2016). Constructing immigrants: Portrayals of migrant groups in British national newspapers, 2010–2012. International Migration Review, 50, 3–40. [Google Scholar]

- Castano E. (2012). Antisocial behavior in individuals and groups: An empathy-focused approach In Deaux K., Snyder M. (Eds.), Handbook of personality and social psychology (pp. 419–445). Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. (1983). The costs of dichotomization. Applied Psychological Measurement, 7, 249–253. [Google Scholar]

- Feather N. T. (1999). Judgements of deservingness: Studies in the psychology of justice and achievement. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 3, 86–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford R. (2011). Acceptable and unacceptable immigrants: How opposition to immigration in Britain is affected by migrants’ region of origin. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 37, 1017–1037. [Google Scholar]

- Gieling M., Thijs J., Verkuyten M. (2011). Voluntary and involuntary immigrants and adolescents’ endorsement of cultural maintenance. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 35, 259–267. [Google Scholar]

- Graham J., Haidt J., Koleva S., Motyl M., Iyer R., Wojcik S. P., Ditto P. H. (2013). Moral foundations theory: The pragmatic validity of moral pluralism. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 47, 55–130. [Google Scholar]

- Hainmueller J., Hangartner D. (2013). Who gets a Swiss passport? A natural experiment in immigrant discrimination. American Political Science Review, 107, 159–187. [Google Scholar]

- Hainmueller J., Hiscox M. (2010). Attitudes toward highly skilled and low-skilled immigration. Evidence from a survey experiment. American Political Science Review, 104, 61–84. [Google Scholar]

- Herda D. (2015). Beyond innumeracy: Heuristic decision-making and qualitative misperceptions about immigrants in Finland. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 38, 1627–1645. [Google Scholar]

- Héricourt J., Spielvogel G. (2014). Beliefs, media exposure and policy preference on immigration: Evidence from Europe. Applied Economics, 46, 225–239. [Google Scholar]

- Howe L. C., Krosnick J. A. (2017). Attitude strength. Annual Review of Psychology, 68, 327–351. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-122414-033600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kymlicka W. (1995). Multicultural citizenship. Oxford, England: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lynn N., Lea S. (2003). A phantom menace and the new apartheid’: The social construction of asylum-seekers in the United Kingdom. Discourse and Society, 14, 425–452. [Google Scholar]

- Maio G. R., Bell D. W., Esses V. M. (1996). Ambivalence and persuasion: The processing of messages about immigrant groups. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 32, 513–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montada L., Schneider A. (1989). Justice and emotional reactions to the disadvantaged. Social Justice Research, 3, 313–344. [Google Scholar]

- Moses J. (2006). International migration: Globalization’s last frontier. London, England: Zed Books. [Google Scholar]

- Newman B. J., Hartman T. K., Lown P. L., Feldman S. (2015). Easing the heavy hand: Humanitarian concern, empathy, and opinion on immigration. British Journal of Political Science, 45, 583–607. doi:10.1017/S0007123413000410 [Google Scholar]

- Nickerson A. M., Louis W. R. (2008). Nationality versus humanity? Personality, identity, and norms in relation to attitudes toward asylum seekers. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 38, 796–817. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2007.00327.x [Google Scholar]

- Ogbu J. (1993). Differences in cultural frame of reference. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 16, 483–506. [Google Scholar]

- Rai T. S., Fiske A. P. (2011). Moral psychology is relationship regulation: Moral motives for unity, hierarchy, equality, and proportionality. Psychological Review, 118, 57–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyna C., Henry P. J., Korfmacher W., Tucker A. (2005). Examining the principles in principled conservatism: The role of responsibility stereotypes as cues for deservingness in racial policy decisions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90, 109–128. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.90.1.109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt G., Weiner B. (1988). An attribution-affect-action theory of behavior: Replications of judgments of help giving. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 14, 610–621. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz S. H. (1992). Universals in the content and structure of values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries In Zanna M. P. (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 25, pp. 1–65). Orlando, FL: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz S. H. (1996). Value priorities and behavior: Applying a theory of integrated value systems In Seligman C., Olson J. M., Zanna M. P. (Eds.), The psychology of values: The Ontario symposium (Vol. 8, pp. 1–24). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Skitka L. J., Bauman C. W., Sargis E. G. (2005). Moral conviction: Another contributor to attitude strength or something more? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88, 895–917. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.88.6.895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verkuyten M. (2004). Emotional reactions to and support for immigrant policies: Attributed responsibilities to categories of asylum seekers. Social Justice Research, 17, 293–314. [Google Scholar]

- Verkuyten M. (2014). Identity and cultural diversity: What social psychology can teach us. Hove, England: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Weiner B. (1995). Judgements of responsibility: A foundation for a theory of social conduct. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yitmen S., Verkuyten M. (2017). Positive and negative behavioral intentions towards refugees in Turkey: The roles of national identification, threat, and shared human identity. Utrecht University: Ercomer. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]