Abstract

Aims and Objectives:

The aim of the study was to determine the knowledge and practices of dental and oral hygiene (OH) students related to the transmission and prevention of the hepatitis B virus (HBV).

Methods:

A cross-sectional analytical design was used and all dental and OH students registered at a university in Pretoria in 2017 were asked to participate. Students were classified as either clinical (senior students who were treating patients) or nonclinical (junior students who had not yet started treating patients) depending on their year of study. A pretested, self-administered questionnaire consisting of 16 closed-ended and 4 open-ended questions relating to the students’ knowledge and practice concerning HBV infection was used. Data were analyzed using SPSS version 23. All data were confidential and anonymity was ensured.

Results:

A total of 292 (78%) students agreed to participate, and of these, 70% were female. The average age was 21.78 years (±2.7) and almost two-thirds (61%) were classified as clinical students. A significant number of nonclinical students reported that the HBV could be transmitted through saliva (P < 0.01), through shaking hands (P < 0.01) and from sharing a toothbrush (P = 0.02) with an infected person. Clinical students correctly reported that HBV could be spread during the birth process from mother to child (P = 0.03). A significant number of nonclinical students stated that they would use antibiotics to prevent the spread of HBV infection (P < 0.01). The majority of respondents (94%) stated that vaccinations should be taken to prevent infection with HBV and >90% of students reported having completed the vaccination schedule.

Conclusion:

Although both the knowledge on the virus and the modes of transmission were very good, more than half did not know that HBV infection can be transmitted through piercing and more than half of the nonclinical students wrongly reported that antibiotics can be used to prevent infection after exposure. The vast majority were vaccinated against HBV.

Keywords: Dental and oral hygiene, hepatitis B virus, infection, knowledge, practice, students

INTRODUCTION

Hepatitis B (HB) infection, one of the most common causes of viral hepatitis, is caused by HB virus (HBV).[1] Infection by HBV remains a global public health problem with changing epidemiology due to several factors including vaccination policies and migration.[2] It is estimated that >600,000 persons die each year worldwide due to the acute or chronic consequences of HB.[3] South Africa had approximately 2.5 million people chronically infected with the disease in 2013/2014, and this could have increased drastically over the past 5 years.[4]

HBV is highly contagious and is between 50 and 100 times more infectious than the human immunodeficiency virus.[1] It is transmitted through blood, semen and vaginal and mucous fluids. People contract the virus through sexual contact, contaminated blood transfusions, unsafe use of needles, from mother to child at birth, close household contact among children in early childhood centers, needlestick injuries in clinical environment and through sharing of personal aids such as toothbrushes, razors, or nail clippers.[1,5]

Due to these routes of transmission, HBV is recognized as a common occupational hazard for health-care workers.[3] Health workers are further at risk due to the nature of HBV which is able to survive in dried blood for up to 1 week.[6]

HBV infection can be prevented with the successful administration of the HBV vaccine.[7,8] Transmission of infection is rare among persons who have been immunized but may be as high as 30% among those who are not immunized.[9] The vaccine was introduced in South Africa in 1995 as part of the National Department of Health Expanded Programme on Immunisation.[10] The vaccine is available to all health-care personnel including students at three intervals: first dosage soon after employment or registration as a health-care student, second dose a month later, and third dose 6 months after the first dose.[10]

All dental schools in South Africa offer the HBV vaccine to their students as part of their training program to ensure immunization and hence prevention of HB infection. First-year dental and oral hygiene (OH) students are screened for HB surface antibody (anti-HBs), and those with a seroprotection rate of >10 IU/ml are considered having good immunogenicity.[10]

Students who had not been previously vaccinated and those with low anti-HB geometric mean titers are then vaccinated at no cost by the University Medical Clinic.

Studies on the knowledge, attitude, and practice of oral health students on HBV infection have reported that students should be provided with continuous information on HBV infections.[1,11,12,13,14] These studies further reported that there was a lower level of knowledge among 1st- and 2nd-year students compared to final-year students. It was also generally found that although the students knew about the risk of infection if not vaccinated, not all students obtained the necessary vaccination schedules.[1,11,12,13,14]

It is imperative as a dental university to gauge the knowledge and practices of dental and OH students related to HBV. No similar study has been done in South Africa on dental and OH students, and the results will assist in the curriculum development and teaching of these students.

The aim of this study was to assess the knowledge and practice patterns in relation to HBV and its transmission among dental and OH students at a university in Pretoria.

METHODS

A cross-sectional analytical study was conducted on undergraduate dental and oral hygiene students registered at a Pretoria Dental University during 2017. There were a total of 372 (328 dental and 44 OH) students registered in 2017, and all of them were invited to participate. Students were informed about the aims and rationale of the study, and written consent was obtained from all of those who participated. The students were allowed to withdraw from the study at any time without any repercussions. Students were divided into clinical (3rd-, 4th-, and 5th-year dental and 2nd- and 3rd-year OH students) and nonclinical (1st- and 2nd-year dental and 1st-year OH students). A student was considered to be “clinical” if they were directly involved in patient treatment and “nonclinical” if they were not. A pretested, modified, self-administered anonymous questionnaire was used to collect information on the sociodemographic characteristics, knowledge, and practice patterns of the students with regard to HB infection.[14] The questionnaire comprised three domains; knowledge which contained 8 questions, mode of transmission (10 questions) and attitudes and practices (8 questions). Correct answers received two points while incorrect answers were scored as zero points. The scores were then added to obtain a domain score.

The collected data was analyzed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 23 (Armonk, NY: IBM Corp). Quantitative variables were summarized as proportions, frequencies, mean with their standard deviations, range, and percentages. Chi-square test was used to determine the association between the variables, and the level of significance was set at P < 0.05. All data was confidential, and anonymity was ensured. Ethical approval was obtained from the University of Pretoria, Faculty of Health Sciences Ethics Committee (Reference Number: 356/2017).

RESULTS

A total of 292 (78%) of the 372 registered undergraduate students participated in the study. There were 177 (61%) clinical and 115 (39%) nonclinical students. Of these, 193 (70%) were female, and the average age was 21.78 years (18–33; ±2.7). There were 253 (87%) dental and 39 (13%) OH students.

The mean overall knowledge domain scores ranged from 8 (50%) to 16 (100%) with the vast majority (92%) achieving a score of >80%. There were no significant differences between the mean knowledge scores and gender and course of study.

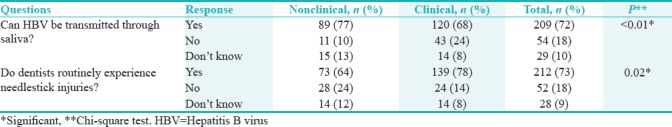

However, there were differences between some responses and the clinical status as shown in Table 1. A significant number of nonclinical students knew that HBV can be transmitted through saliva (P < 0.01) and a significant number of clinical students reported that dentists routinely experience needlestick injuries (P = 0.02).

Table 1.

Significant differences between clinical and nonclinical students’ knowledge regarding hepatitis B virus

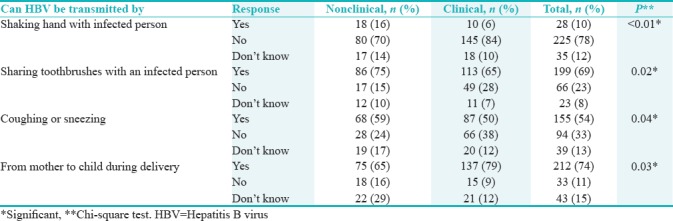

The mean scores for the modes of transmission domain were also relatively high. More than two-thirds (69%) of the respondents achieved a score of >80%, and there were no significant differences between the genders and the course of study. However, the clinical students had a significantly higher mean score compared to the nonclinical students (P = 0.01) which indicated that their levels of knowledge on modes of transmission were better than the nonclinical students. A significant number of nonclinical students incorrectly stated that HBV could be spread through shaking hands with an infected person (P < 0.01) and through coughing or sneezing (P = 0.04) [Table 2]. More nonclinical students correctly reported that HBV could be spread from sharing a toothbrush with an infected person (P = 0.02) while more clinical students were aware that HBV could be spread during the birth process (P = 0.03) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Significant differences between clinical and nonclinical students’ regarding hepatitis B virus transmission

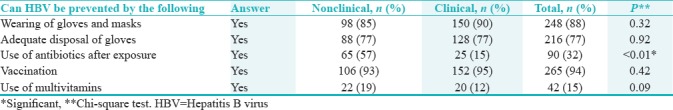

Regarding the practices employed by students in preventing the spread of HBV infection, most of them reported to use universal personal protective equipment such as gloves and masks [Table 3]. A significant number of nonclinical students incorrectly stated that they would use antibiotics to prevent the spread of HBV infection (P < 0.01). The vast majority of all respondents (94%) stated that vaccinations should be taken to prevent infection with HBV.

Table 3.

Difference between clinical and nonclinical students’ responses regarding the prevention of hepatitis B virus infection

In the open-ended section, students reported that sterilization of instruments (9%) and incineration of needles (11%) could be used in the prevention of HBV infection.

Regarding the screening for the HBV antibodies (anti-HBs), 225 (80%) students admitted to be screened before vaccination, 37 (12%) students were not screened, and 13 (5%) could not recall being screened. A total of 256 (92%) students reported having completed the vaccination schedule, 14 (5%) stated that they did not complete the schedule, and 8 (3%) could not recall whether they did or did not complete the entire schedule. The vast majority of both clinical (94%) and nonclinical students (88%) reported that they had completed the vaccination schedule.

DISCUSSION

Similar to other studies, the majority of respondents had an acceptable level of knowledge and displayed acceptable practices in relation to the prevention of the spread of HBV.[14,15] The clinical students had a significantly higher mean score, and this could be due to their exposure to patients in the clinical setting, the lectures received in pathology and microbiology and the time spent interacting with supervisors during clinical sessions. The majority (72%) of the students reported that HBV transmission can occur through saliva and this was similar to other studies.[14,16,17] Interestingly, nonclinical students were more aware that HBV could be transmitted through saliva compared to clinical students. This could be due to the fact that the lectures on HBV are offered in the 2nd and 3rd year, and as a result, the clinical students may have forgotten this and were unaware of the different modes of transmission.

Not surprisingly, clinical students were more aware of needlestick injuries compared to nonclinical as they were treating patients and either experienced needlestick injuries or were reminded on the protocol to follow in the event of a needlestick injury.

A significant number of nonclinical students incorrectly perceived that HBV could be spread through shaking hands with an infected person (P < 0.01) and through coughing or sneezing (P = 0.04). The nonclinical students, therefore, implied that HBV can be transmitted through casual contact which is incorrect.[18] This could be due to the fact that perhaps these aspects were not covered in the junior years, but once students entered into clinics, practical and relevant information was shared. This was confirmed by the positive results obtained from clinical students who reported that HBV could be spread by sharing a toothbrush with an infected person (P = 0.02) and during the birth process (P = 0.03).

Basic infection control practices include the use of physical barriers such as masks and gloves to prevent infections. Almost all of the students (88%) reported that the wearing of gloves and masks could prevent the spread of HBV. More information should be given to students regarding the modes of transmission and the means of preventing the spread of this disease to improve their knowledge on the prevention of this disease.

More than half of nonclinical students (57%) wrongly reported that antibiotics could be used to prevent HBV infection after exposure. Studies report that the prophylaxis depends on whether a person has had prior vaccination or not but in all cases, HB immune globulin is given followed by normal vaccinations in the case of those who were never vaccinated.[19]

Based on these findings, it is clear that although the students achieved high scores, there were still gaps in their knowledge and as a result, some of them answered incorrectly.

The fact that 80% of students were screened for HBV antibodies (anti-HBs) showed that the dental school has a working policy in administering the vaccine. Although vaccination is compulsory, students were not being followed up to ensure that they had received all the vaccinations. It was comforting to note that 92% reported to have taken the HBV vaccine and that clinical (94%) and nonclinical students (88%) reported to have completed the vaccination schedule. This was much higher compared to a similar study done in India which reported only 45% of dental students having been vaccinated.[13]

LIMITATIONS

Due to ethical reasons, no blood samples were drawn, and as a result, the antibody titer was not confirmed. Hence, the students’ response regarding their vaccination status could not be verified.

CONCLUSION

Although both the knowledge on the virus and the modes of transmission were acceptable, more than half did not know that HBV infection can be transmitted through piercing and more than half of the nonclinical students wrongly reported that antibiotics can be used to prevent infection after exposure. The vast majority were vaccinated against HBV.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The above findings highlight the necessity of continuous information on HBV infection and infection control policies. It is recommended that training at the beginning of each academic year might be more effective in ensuring their level of knowledge remains high. It might even be helpful to assess the knowledge of students regarding infection control, spread of diseases and methods of prevention annually. A strategy should be executed to ensure that all the required vaccinations are completed for all students joining the dental school.

DECLARATION OF PATIENT CONSENT

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

FINANCIAL SUPPORT AND SPONSORSHIP

Nil.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Nagpal B, Hegde U. Knowledge, attitude, and practices of hepatitis B infection among dental students. Int J Med Sci Public Health. 2016;5:1123–7. [Google Scholar]

- 2.European Association for the Study of the Liver. Electronic address: easloffice@easloffice.eu; European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL 2017 clinical practice guidelines on the management of hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2017;67:370–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Darwish MA, Al Khaldi NM. Knowledge about hepatitis B virus infection among medical students in university of dammam, eastern region of Saudi Arabia. Life Sci J. 2013;10:860–7. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spearman CW, Sonderup MW. Preventing hepatitis B and hepatocellular carcinoma in South Africa: The case for a birth-dose vaccine. S Afr Med J. 2014;104:610–2. doi: 10.7196/samj.8607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brailo V, Pelivan I, Škaricić J, Vuletić M, Dulcić N, Cerjan-Letica G, et al. Treating patients with HIV and hepatitis B and C infections: Croatian dental students’ knowledge, attitudes, and risk perceptions. J Dent Educ. 2011;75:1115–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bond WW, Favero MS, Petersen NJ, Gravelle CR, Ebert JW, Maynard JE, et al. Survival of hepatitis B virus after drying and storage for one week. Lancet. 1981;1:550–1. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(81)92877-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hepatitis B vaccines. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2009;84:405–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017. World Health Organization. Global Hepatitis Report 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weinbaum CM, Williams I, Mast EE, Wang SA, Finelli L, Wasley A, et al. Recommendations for identification and public health management of persons with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2008;57:1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Department of Health. 4th ed. National Department of Health in South Africa; 2012. National Department of Health in South Africa. Expanded Programme on Immunization in South Africa (EPI-SA) [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vasanthakumar AH, D’Cruz AM. Awareness regarding hepatitis B immunization among preclinical Indian dental students. J Oral Health Oral Epidemiol. 2013;2:97–101. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bansal M, Vashisth S, Gupta N. Knowledge and awareness of hepatitis B among first year undergraduate students of three dental colleges in Haryana. Dent J Adv Stud. 2013;1:15–7. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saini R, Saini S, Sugandha R. Knowledge and awareness of hepatitis B infection amongst the students of rural dental college, Maharashtra, India. Ann Niger Med. 2010;4:18. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alavian SM, Mahboobi N, Mahboobi N, Savadrudbari MM, Azar PS, Daneshvar S, et al. Iranian dental students’ knowledge of hepatitis B virus infection and its control practices. J Dent Educ. 2011;75:1627–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khandelwal V, Khandelwal S, Gupta N, Nayak UA, Kulshreshtha N, Baliga S, et al. Knowledge of hepatitis B virus infection and its control practices among dental students in an Indian city. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2017 doi: 10.1515/ijamh-2016-0103. pii:/j/ijamh.ahead-of-print/ijamh-2016-0103/ijamh-2016-0103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hu SW, Lai HR, Liao PH. Comparing dental students’ knowledge of and attitudes toward hepatitis B virus-, hepatitis C virus-, and HIV-infected patients in Taiwan. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2004;18:587–93. doi: 10.1089/apc.2004.18.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mast EE, Margolis HS, Fiore AE, Brink EW, Goldstein ST, Wang SA, et al. A comprehensive immunization strategy to eliminate transmission of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) part 1: Immunization of infants, children, and adolescents. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2005;54:1–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stockholm: ECDC; 2016. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Epidemiological Assessment of Hepatitis B and C Among Migrants in the EU/EEA. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bader MS, McKinsey DS. Postexposure prophylaxis for common infectious diseases. Am Fam Physician. 2013;88:25–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]