Abstract

Exploiting cells as vehicles combined with nanoparticles combined with therapy has attracted increasing attention in the world recently. Red blood cells, leukocytes and stem cells have been used for tumor immunotherapy, tissue regeneration and inflammatory disorders, and it is known that neutrophils can accumulate in brain lesions in many brain diseases including depression. N-Acetyl Pro–Gly–Pro (PGP) peptide shows high specific binding affinity to neutrophils through the CXCR2 receptor. In this study, PGP was used to modify baicalein-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles (PGP-SLNs) to facilitate binding to neutrophils in vivo. Brain-targeted delivery to the basolateral amygdala (BLA) was demonstrated by enhanced concentration of baicalein in the BLA. An enhanced anti-depressant effect was observed in vitro and in vivo. The mechanism involved inhibition of apoptosis and a decrease in lactate dehydrogenase release. Behavioral evaluation carried out with rats demonstrated that anti-depression outcomes were achieved. The results indicate that PGP-SLNs decrease immobility time, increase swimming time and climbing time and attenuate locomotion in olfactory-bulbectomized (OB) rats. In conclusion, PGP modification is a strategy for targeting the brain with a cell–nanoparticle delivery system for depression therapy.

KEY WORDS: PGP peptide, Neutrophils, Dual-brain targeting delivery, Solid lipid nanoparticle, Depression, Baicalein, Olfactory bulbectomy rats

Graphical abstract

PGP was used to modify solid lipid nanoparticles (PGP-SLNs) loaded with baicalein for binding to neutrophils in vivo. Cell–nanoparticle brain-targeted delivery to the basolateral amygdala and increased anti-depressant effect was obtained in vitro and in vivo. The mechanism involved inhibition of apoptosis induced by mitochondria and reduction of lactate dehydrogenase release.

1. Introduction

Depression is one of the most common mental disorders in the world and is frequently observed as a comorbidity in clinical settings1. About 350 million people currently suffer from depression. The World Health Organization has predicted that, by 2020, depression will be one of the two top causes of global health burden and disability2. The health effects of depression are due to its contribution to mental disorders such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, schizoaffective disorder and drug addiction. Despite extensive studies, depression's etiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment has not been fully elucidated. In fact, depression covers a broad spectrum of disorders, which are multifactorial in origin including genetic, developmental, and environmental factors3., 4.. On one hand, it is believed that depression is associated with the alteration of neurotransmitter expression with structural changes within the brain and in the hypothalamus–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis; on the other hand, there is growing evidence indicating that inflammation accompanied by increased oxidative and nitrosative stress may play a crucial role in the pathogenesis of depression5., 6..

Accumulated evidence has shown that an inflammatory process in the brain is found in several psychiatric diseases including depression7. Leukocytes recruitment means monocytes and neutrophils can cross the blood–brain barrier, a major barrier for brain disease therapy. Phagocytosis and the unique extravasation property of leukocytes make it possible to exploit these cells as a carrier system for targeted drug delivery8. In fact, we have use monocytes as drug carriers for many brain disease therapies including depression9., 10., 11.. N-Acetyl Pro–Gly–Pro (PGP) exhibits high binding affinity and specificity to neutrophils through the CXCR2 receptor12., 13.. In our previous studies PGP was used as a ligand to modify nanoparticles for binding with neutrophils in vivo, which are known to accumulate in lesions in ischemic stroke. Hence, it may be possible to design solid lipid nanoparticles modified with PGP peptide (PGP-SLNs) for brain-targeted delivery through neutrophils for depression therapy.

Baicalein (BA, 5,6,7,-trihydroxyflavone), one of the most active natural plant flavonoids, is found in the dry roots of Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi. It exhibits several beneficial actions, including effects in the central nervous and immune systems14., 15.. It has been widely used for the treatment of inflammation, hypertension, cardiovascular disease and bacterial infection, with the mechanism related to anti-neuroinflammation. It is reported that BA treatment improved motor impairments, attenuated brain damage, suppressed proinflammatory cytokines, modulated astrocyte and microglia activation, and blocked the activation of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signals in rotenone-induced rats16.

Solid lipid nanoparticles (SLNs) are nanospheres made from solid lipids with a diameter of approximately 50–1000 nm. A solid lipid matrix, including glycerides, fatty acids or waxes, and stabilized by physiologically-compatible emulsifiers such as phospholipids, bile salts, Tween 80, polyoxyethylene ethers, or polyvinyl alcohol were often used for SLNs due to their low toxicity. The most common strategy for nanocarrier targeting to the brain is receptor-mediated endo-/transcytosis and cell-mediated delivery. This pathway depends on interaction of the surface ligand nano-carriers (transferrin, transferrin-receptor binding antibody, lactoferrin, melanotransferrin, folic acid and a-mannose or cRGD) with specific receptors, formation of endocytotic-vesicles that envelop the nanocarriers, transcytosis across the BBB, and exocytosis of the nano-carriers in the CNS parenchyma17., 18..

Hence, PGP peptide was used as a ligand for neutrophils as reported previously19, allowing brain drug delivery of nanoparticles loaded with BA. The targeting efficiency, anti-oxidative mechanism, and anti-depressant effects in model animal were evaluated. An enhanced therapeutic outcome of PGP-SLNs loaded with BA (PGP-BA-SLNs) was observed in this study.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

Glyceryl monostearate (GM) and poloxamer 188 were obtained from China National Pharmaceutical Group Corporation (Beijing, China); BA was purchased from Meilunbio (Dalian, China); coumarin 6 (C6) and 1,1′-dioctadecyl-3,3,3′,3′-tetramethylindocarbocyanine (DiI) were from FanboBio chemicals (Beijing, China); 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DPPC) was obtained from Merck (Schaffhausen, Switzerland); PGP-PEG-DSPE and T7-PEG-DSPE were synthesized in our laboratory as previously reported19., 20.. A cell counting kit (CCK-8) was obtained from Sigma–Aldrich (Schnelldorf, Germany); the lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release assay kit was obtained from Beyotime (Nantong, China); ultrafiltration tubes were from Millipore (3 kDa, Bedford, MA, USA); Hank's balanced salt solution (HBSS) was obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA).

All of the animal experiments were performed in compliance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and the procedures were approved by the Ethics Committee of The Second Hospital Affiliated Heilongjiang University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (Harbin, China; SYXK-2013-012).

2.2. Cell culture

The PC12 cell line (a neuron-like rat pheochromocytoma cell line) and the HL-60 cell line (the human promyelocytic leukemia cell line) were purchased from the Cell Bank at the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). HL-60 cells were cultured in Iscove's modified Dulbecco minimum essential medium (IDMEM; Gibco Ltd., Paisley, UK) with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin–streptomycin, and differentiated into PMN-like cells by adding 1.3% DMSO for 96 h as previously reported21. Cells were maintained in an incubator at a controlled atmosphere of 37 °C, 95% relative humidity and 5% CO2.

PC12 cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 5% (v/v) heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), l-glutamine (2 mmol/L), 100 units/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 at 37 °C. The medium was changed every 2–3 days.

2.3. Preparation and characterization of solid lipid nanoparticles

GM and DPPC were dissolved in 2 mL ethanol to form an oil phase and 10 mL of poloxamer 188 solution was heated to 80 °C to form a water phase. The water phase was added into the oil phase at 80 °C with 2 min of stirring. The mixture was subjected to 500 W of ultrasonic treatment for 2 min using a high-intensity probe ultrasonicator under 80 °C (JY92-2D; Xinzhi Equ.Inst., Zhejiang, China). The suspension was cooled at 4 °C immediately to obtain plain SLNs. To obtained a high entrapment efficiency (EE) of BA, different kinds of lipid, pH values of the water phase, the ratio of drug to GM, and the amount of poloxamer were evaluated.

For drug loading, 10 mg BA was added into the oil phase to obtained solid lipid nanoparticle loaded with BA (BA-SLNs).

For PGP or T7 modified BA-SLNs, PGP-PEG-DSPE and T7-PEG-DSPE were used at the ratio of 5% (mol/mol) of DPPC to obtain PGP-BA-SLNs and T7-BA-SLNs (T7 as scrambled peptide-modified nanoparticle).

For fluorescence assay, C6 or DiI was added into the lipid formulation to prepare C6-loaded SLNs/PGP-SLNs/T7-SLNs (C6-SLNs, C6-PGP-SLNs, C6-T7-SLNs) or DiI-loaded SLNs/PGP-SLNs/T7-SLNs (DiI-SLNs, DiI-PGP-SLNs, DiI-T7-SLNs).

The PGP-BA-SLNs and BA-SLNs were observed by transmission electron microscopy (TEM, JEM-2010F, JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) following negative staining with 1% uranyl acetate solution. The average particle size and zeta potential of these two SLNs were determined by dynamic light scattering using a Zetasizer Nano ZS (Malvern Instruments, Malvern, UK).

For EE determination, SLNs were added to an ultrafiltration tube and subjected to centrifugation at 6000 × g. The solution in the lower chamber was withdrawn for HPLC determination for free BA. The SLN suspension was disrupted by a mixture of dimethyl formamide and water at a ratio of 3:7 for the determination of total BA. EE was calculated according to the Eq. (1):

| (1) |

2.4. Affinity efficiency in vitro and in vivo

2.4.1. The binding of PGP-SLNs with HL-60

To investigate the affinity of PGP-SLNs for neutrophils, C6-SLNs, C6-PGP-SLNs, C6-T7-SLNs and C6 were added to HL-60 cells and incubated for 30 min at 37 °C. Subsequently, the HL-60 cells were washed by centrifugation to remove non-adherent SLNs and visualized under an IX2-RFACA fluorescent microscope (Olympus, Osaka, Japan). The cells were then disrupted by ultrasonic and Triton-100 treatment for fluorescence determination with a microplate reader (Thermo Multiskan MK3, USA).

2.4.2. The binding of PGP-SLNs with neutrophils in vivo

Nine rats were divided into 3 groups and injected with DiI-SLNs, DiI-PGP-SLNs, DiI-T7-SLNs and DiI (10 mg/kg GM, i.v.). The right femoral artery was cannulated with polyethylene tubing for blood sampling. One milliliter of whole blood was collected into heparinized tubes at 15 min and 1 h after administration and lysed in RBC lysis buffer (eBioscience, San Diego, CA). The fluorescence of DiI in neutrophils was determined after separation by flow cytometry. The binding efficiency of SLNs with the neutrophils was measured by DiI fluorescence. DiI-T7-SLNs were used as a scrambled control.

2.4.3. Stability of BA in SLN-neutrophils

BA, BA-SLNs, and PGP-BA-SLNs were incubated with HL-60 cells at 37 °C. Cells were disrupted by ultrasonification and Triton-100 treatment after 15, 30 min, 1 and 2 h of incubation. Then, 60% methanol was added to the suspension which was centrifuged at 9000 × g and filtered for HPLC assay. In addition, another BA solution that was not incubated with HL-60 was also subjected to HPLC assay as a control. The ratio of sample to control BA solution was used to determine the degradation of BA in SLN-neutrophils.

2.5. Anti-oxidative activity in vitro

2.5.1. Measurement of cell viability

PC12 cells were grown in 96-well plates with a final density of 5 × 104 cells/well and treated with ferrous sulfate (FS, 10 μmol/mL) 12 h before addition of nanoparticles. BA-SLNs, PGP-BA-SLNs and BA solution were given to PC12 cells for 1 h incubation while PBS was used in the control group. After incubation, the culture medium was discarded and cells were gently rinsed with HBSS three times. Cell viability was detected using the CCK-8 according to the manufacturer's instructions. OD values were measured at 450 nm. Cell viability was calculated using Eq. (2):

| (2) |

The results for the absorbance of treated cells were calculated as percentages of the absorbance in untreated control cells.

2.5.2. Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) assay

BA-SLNs, PGP-BA-SLNs and BA solution were added to PC12 cells after treatment with FS for 12 h while PBS was used in the control group. The supernate was collected for the determination of the release of LDH using the assay kit. The absorbance was measured at a wavelength of 490 nm using a microplate reader, calculated according to the following Eq. (3):

| (3) |

2.5.3. Determination of mitochondrial transmembrane potential

After a 12 h pre-treatment with FS, PC12 cells were incubated with BA-SLNs, PGP-BA-SLNs and BA solution (equivalent 100 μmol/L) for 1 h. The cells were incubated with rhodamine 123 staining stock solution (5 g/L) for 20–30 min at 37 °C. Mitochondrial transmembrane potential changes were indirectly determined by measuring the change in rhodamine 123 fluorescence using a flow cytometer at an emission wavelength of 525 nm and an excitation wavelength of 488 nm. The samples were examined and quantified as quickly as possible.

2.6. Brain distribution

Rats were subjected to the olfactory bulbectomy (OB) procedure as previously described9. Briefly, rats were anesthetized and the skull was exposed, and burr holes were drilled (coordinates: 7 mm anterior to bregma and 2 mm from the midline). The bilateral olfactory bulbs were removed by suction, and the burr holes were filled with a hemostatic sponge. The rats were allowed to recover for 14 days after surgery, with daily handling during the entire recovery period. Penicillin was injected intraperitoneally (20 U/day) for 1 week to decrease the possibility of infection.

Nine OB rats were divided into three groups and were administrated of DiI-SLNs, DiI-PGP-SLNs or DiI for 7 days. Rats then were sacrificed and the tissue from the basolateral amygdala (BLA) region was collected and homogenized with an electrical disperser. The homogenate was subjected to 10,000 × g centrifugation at 4 °C for 20 min and the fluorescent of DiI was determined using a fluorescence photometer (Bio Tek FLx800, USA).

2.7. Behavioral evaluation

2.7.1. Forced swim test

The forced swim test (FST) was performed as previously reported10. Briefly, rats were placed for 15 min in a tall plastic cylinder that was filled to a depth of 30 cm with 23–25 °C water. Twenty-four hours later, the rats received a single dose of BA-SLNs, PGP-BA-SLNs, BA solution (equivalent to 50 mg/kg BA, i.v.) or PBS as a control.

Immobility was defined as the minimum movement required to passively keep the animal's head above the water without other motions. Swimming was related to the rats' active behavior to escape from the water. Climbing was defined as upward-directed movements of the forepaws against the wall. The results are expressed as the time that the animals spent immobile during the 5 min test.

2.7.2. Locomotor activity assay in OB rats

The rats were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (50 mg/kg, i.p.), and bilateral OB was performed as described above. After a 14-day recovery, the rats were treated with the BA-SLNs, PGP-BA-SLNs, BA solution (equivalent to 50 mg/kg BA, i.v.) or PBS for 7 days before locomotor activity was assessed. Sham-operated animals were subjected to the same treatment, with the exception that the olfactory bulbs were left intact.

Locomotion was measured using the Animal Locomotor Video Analysis System (JLBehv-LAR-8, Shanghai Jiliang Software Technology Co. Ltd., Shanghai, China), which consists of eight identical black Plexiglas chambers (40 cm × 40 cm × 65 cm) in light- and sound-controlled cubes. Locomotor activity for each rat was analyzed using DigBehv analysis software (Shanghai Jiliang Software Technology Co. Ltd., Shanghai, China) and is expressed as the total distance traveled (in millimeters) during 15 min11.

2.8. Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± SD. The data were analyzed using one-way or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey's post hoc test. A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Preparation and characterization of SLNs

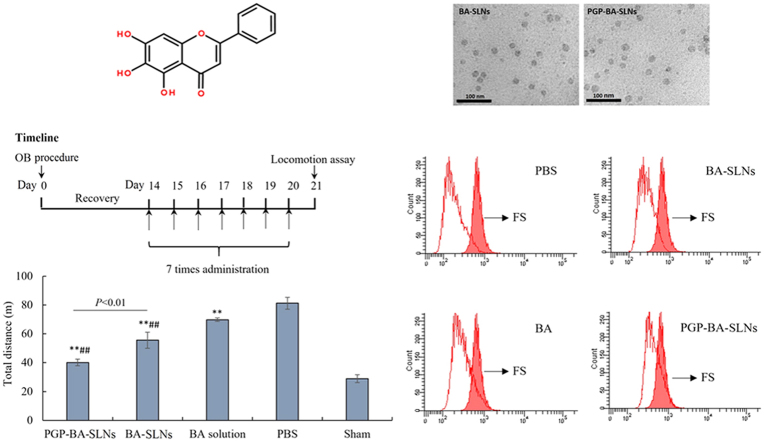

It has been reported that small particles easily cross the blood–brain barrier, hence SLNs with a diameter under 100 nm and high loading efficiency were generated in this study22. Considering that BA is a trihydroxyflavone (Fig. 1A), different kind of lipids, pH values of water phase, the ratio of drug to GM, and the amount of poloxamer were evaluated in the preparation. As a result, different kinds of lipids have some influence on the EE but have a greater influence on particle size (Fig. 1B). Glyceryl behenate showed the lowest EE and largest size; stearic acid has similar EE and larger size compared with GM. Hence, GM was chosen as lipid used in this study.

Figure 1.

The influence of formula factors on the entrapment efficiency (EE) and particle size. All the data are expressed as mean ± SD. (A) Molecular structure of baicalein (BA); the effect of (B) different kinds of lipid, (C) pH value of the water phase, (D) ratio of drug to GM, and (E) amount of poloxamer on the EE and particle; (F) TEM photo of final BA-SLNs and PGP-BA-SLNs.

As shown in Fig. 1C, the pH value of the water phase has a great effect on the EE and size. As a trihydroxyflavone, BA has similar hydrophobic property to lipid material, such as GM, at low pH. A small size is easier to obtain under the conditions where BA and GM are compatible during emulsification. Almost 100% EE was obtained at different ratios of drug to lipid, which means the compatibility of GM with BA is sufficient for a high loading efficiency (Fig. 1D). The particle size decreased with the rising amount of poloxamer, an efficiency emulsifier (Fig. 1E). Taken together, a drug to GM ratio of 1:5, a water phase pH value of 5.5 and 450 mg of poloxamer were used in the final formula. EEs of 98.7% and 99.1%, zeta potentials of –13.5 mV and –12.6 mV were obtained for BA-SLNs and PGP-BA-SLNs, respectively. Particles were semi-round as observed by TEM (Fig. 1F).

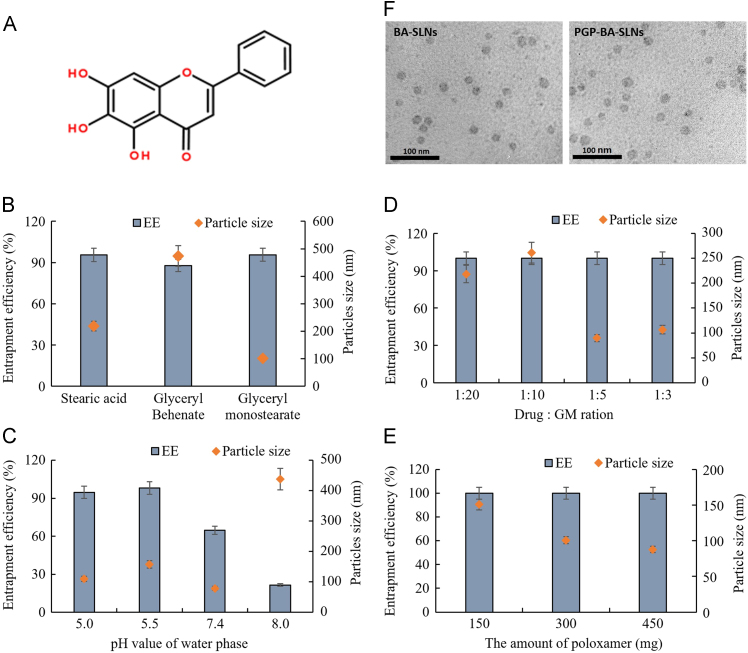

3.2. Affinity in vitro and in vivo

To reach the targeting goal, high affinity binding was essential for the SLNs. The fluorescence intensity of C6-PGP-SLNs was much higher than C6-SLNs and C6-T7-SLNs as visualized under the fluorescent microscope (Fig. 2A). The quantitative results for HL-60 cells showed that the uptake of C6-PGP-SLNs was 3.6-fold higher than that of C6-SLNs and 4.3-fold higher than that of C6-T7-SLNs (Fig. 2B). Both the qualitative and quantitative results indicated that the PGP peptide greatly enhanced the uptake of SLNs into HL-60 cells. There was almost no fluorescence observed in C6 group which means C6 did not affect the determination of affinity of SLNs for HL-60 cells.

Figure 2.

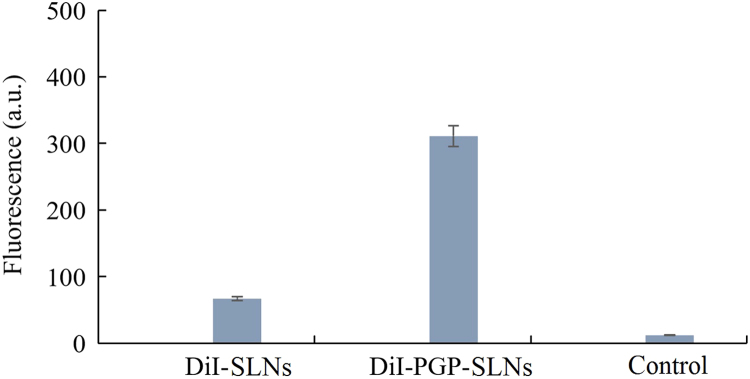

Binding efficiency of PGP-SLNs with neutrophils in vitro and in vivo. HL-60 cells were incubated with C6-PGP-SLNs, C6-SLNs, C6-T7-SLNs and C6 for 30 min at 37 °C. Subsequently, HL-60 cells were centrifuged to remove non-adherent SLNs and visualized under a fluorescent microscope. The bar represents 50 μm (A). Cells were disrupted by ultrasonification and Triton-100 treatment for fluorescence determination with a microplate reader (B). DiI-BA-SLNs, DiI-PGP-BA-SLNs, and DiI-T7-BA-SLNs were administered to rats. Neutrophils were separated for determination of the binding with SLNs at different times in vivo (C). BA, BA-SLNs, and PGP-BA-SLNs, were incubated with HL-60 cells at 37 °C. The BA concentration was determined by HPLC after 15, 30 min, 1, and 2 h incubation to determine the degradation of BA in SLN–neutrophils (D).

As shown in Fig. 2C, the fluorescence of neutrophils in DiI-PGP-SLN group was the strongest among four groups within 1 h. The fluorescence of the DiI-PGP-SLN group increased with time. Compared with DiI-SLNs, the fluorescence DiI-PGP-SLNs was 6-fold higher at 15 min and 7-fold higher at 1 h. DiI-T7-SLNs and DiI showed much lower affinity for neutrophils. Thus, DiI-PGP-SLNs exhibited a very high affinity for neutrophils in vivo, making it feasible to construct a nanoparticle–cell co-vehicle.

The BA concentration of BA-SLNs and PGP-BA-SLNs did not show significant difference from BA solution of control after 2 h of incubation with HL-60 cells (Fig. 2D). The BA group exhibited a small decrease compared with control at the end of 2 h of incubation. This illustrates that BA in BA-SLNs and PGP-BA-SLNs was not degraded in HL-60 cells while slight degradation was evident after 2 h of incubation for BA group. Hence, the protective effect of SLNs for BA in neutrophils supports the feasibility of drug delivery.

HL-60 human leukemia cells, which can be differentiated into neutrophilic or monocytic cells23, are a widely employed model system for the analysis of signal transduction processes mediated via regulatory heterotrimeric guanine nucleotide-binding proteins (G proteins). HL-60 cells express formyl peptide-, complement C5a-, leukotriene B4 (LTB4)- and platelet-activating factor receptors, receptors for purine and pyrimidine nucleotides, histamine H1- and H2-receptors, β2-adrenoceptors and prostaglandin receptors. T7 was used as a scrambled peptide which showed low affinity for HL-60 cells. Thus, the affinity of C6-PGP-SLNs to HL-60 results from the specific binding of PGP to neutrophils. Hence, the high affinity of PGP-SLNs for HL-60 cells means the SLNs can be expected to bind with neutrophils in vivo for a brain targeting effect.

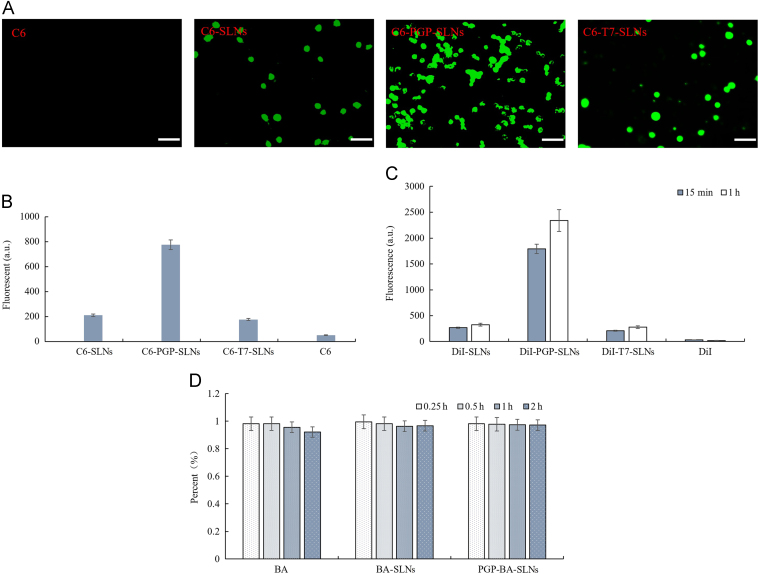

3.3. Anti-oxidative activity in vitro

The exposure of PC12 cells to 10 μmol/L FS decreased cell viability by over 60%. BA enhanced the cell viability by up to 47%. Both PGP-BA-SLNs and BA-SLNs could increase cell viability up to 60%, and there was no significant difference between them (Fig. 3A). Treatment of PC12 cells with 10 μmol/L of FS for 12 h significantly increased the LDH efflux. BA, PGP-BA-SLNs and BA-SLNs could greatly alleviate the LDH efflux while PGP-BA-SLNs and BA-SLNs have a greater effect than BA. There was no significant difference between PGP-BA-SLNs and BA-SLNs (Fig. 3B). The results of the flow cytometer assay demonstrated that 12 h exposure of PC12 cells to FS resulted in 38.7 ± 3.7% apoptosis. Treatment with BA, PGP-BA-SLNs and BA-SLNs decreased the rate of apoptosis to 32.8 ± 2.1%, 20.7 ± 2.9% and 28.1 ± 1.8%, respectively. The protective effect of BA-SLNs was better than that of BA while the protection afforded by PGP-BA-SLNs was the most effective (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3.

Evaluation of anti-oxidative activity of PGP-BA-SLNs in vitro. (A) The influence of BA-SLNs, PGP-BA-SLNs and BA solution on viability of PC12 cells. (B) The influence of BA-SLNs, PGP-BA-SLNs and BA solution on LDH release from PC12 cells. (C) The protective effect of BA-SLNs, PGP-BA-SLNs and BA solution on apoptosis initiated by mitochondria in PC12 cells as determined by flow cytometry. PC12 cells, pretreated with ferrous sulfate (FS, 10 μmol/mL) for 12 h, were incubated with SLNs for 1 h in all experiments. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, compared with control group; #P<0.05, ##P<0.01, compared with BA group.

Numerous studies on experimental models have revealed the favorable role of flavonoids on mitochondrial function and structure. Mitochondria are the main production site for ATP in animal cells, which is due to the work of the electron transfer chain (ETC) and complex V (ATP synthase) enzyme activity in the inner mitochondrial membrane24. Likewise, mitochondrial-controlled cell death (the so-called intrinsic apoptotic pathway) is necessary during development and in maintenance of tissue homeostasis throughout life25. LDH is released from cells with damaged membranes, thus the level of LDH in the culture indicates the extent of cellular injury. The inhibition of LDH release and apoptosis by mitochondria is very important in depression therapy.

In this study, PGP-BA-SLNs and BA-SLNs enhanced the effect of BA in reducing LDH release and apoptosis, with no significant different between these treatments, while both showed stronger effect than BA solution. This might result from the enhanced uptake of nanoparticles in PC12 cells, but not the targeting effect of PGP which is a ligand for neutrophils, not neurons. The enhanced inhibition of LDH release and mitochondrially induced apoptosis was still observed for nanoparticles, suggesting that a better anti-oxidative effect could be expected in vivo.

3.4. Brain distribution

Next, a brain distribution of PGP-SLNs in vivo was measured by fluorescence. BLA regions were taken from OB rats. The accumulation of DiI-PGP-SLNs in BLA was 4.6-fold higher than that of DiI-SLNs (Fig. 4). This indicates that PGP-SLNs enhanced the drug concentration in BLA greatly. It is difficult to determine the fluorescence from the DiI group, indicating that DiI exerted no influence on the targeting. Hence, a brain targeting effect was observed in vivo.

Figure 4.

The fluorescence of DiI-PGP-SLNs and DiI-SLNs in the basolateral amygdala (BLA). Nine olfactory bulbectomy (OB) rats were administered DiI-BA-SLNs, DiI-PGP-BA-SLNs or DiI (10 mg GM/kg, i.v.) for 7 days, after which the rats were sacrificed and the tissue from the BLA region was collected and homogenized. The fluorescence of DiI was assayed using a fluorescence photometer.

BLA is a major brain region associated with emotional and psychiatric disorders. It interconnects with stress-modulated neural networks to generate emotion- and mood-related behaviors. It was reported that 3 h per day of restraint stress for 14 days led mice to exhibit long-term depressive behaviors26., 27.. These behavioral changes corresponded with morphological and molecular changes in BLA neurons, including chronic stress-elicited increases in arborization, dendritic length, and spine density of BLA principal neurons. The expression of synaptophysin (SYP) and postsynaptic density protein 95 (PSD-95) at BLA neuronal synapses was also enhanced by chronic stress, which was reversed post-treatment. Chronic stress-elicited depressive behavior may be due to hypertrophy of BLA neuronal dendrites and increased PKA (protein kinase A)-dependent CP-AMPAR (calcium-permeable α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptor) levels in BLA neurons. Hence, the brain targeting effect reflected by increase concentration of drug in BLA resulted from a strong binding effect of PGP with neutrophils, which is very important for the possible enhanced therapy of BA in the next study in vivo.

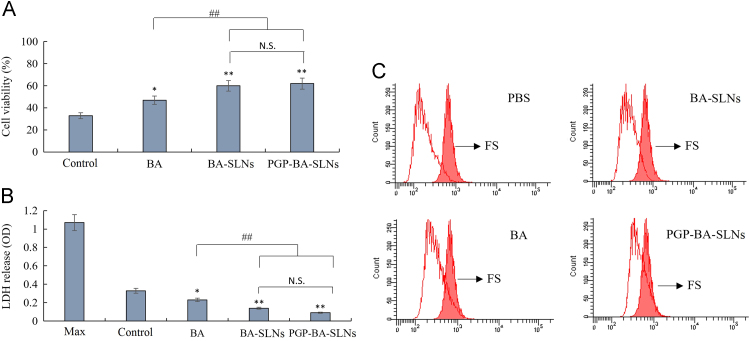

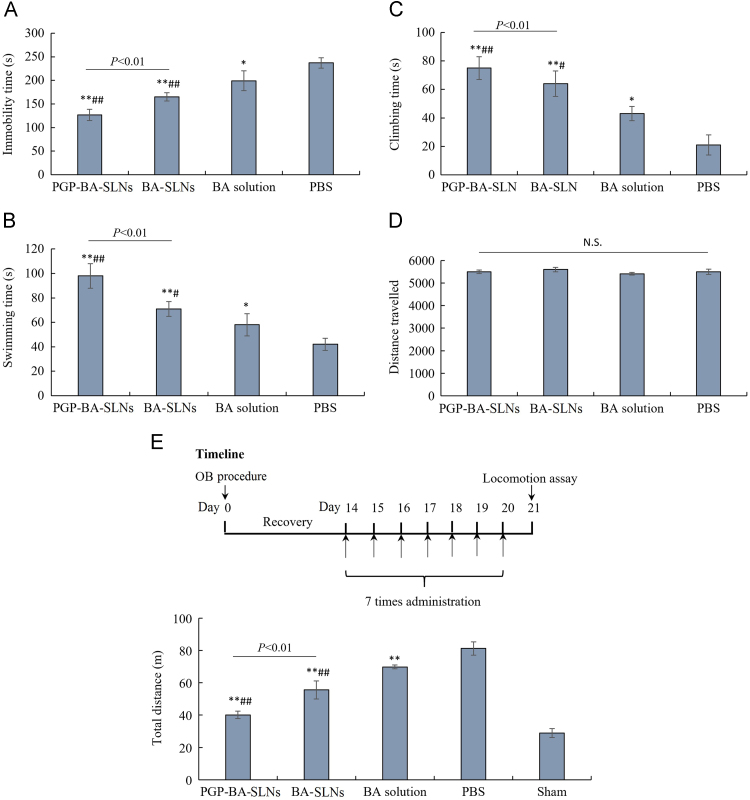

3.5. Behavioral evaluation

As shown in Fig. 5A–C, a single dose of BA decreased the immobility time and increased swimming time and climbing in FST within 5 min compared with the control group. Both BA-SLNs and PGP-BA-SLNs could decrease the immobility time and increase swimming time and climbing time compared with the PBS control group. The effect of BA-SLNs and PGP-BA-SLNs was much better than BA solution; the protective effect of PGP-BA-SLNs was higher than that of BA-SLNs in FST within 5 min, indicating that the modification of PGP can promote the anti-depressant effect of BA though the binding of PGP to neutrophils. None of the groups showed any effect on normal locomotion (Fig. 5D).

Figure 5.

Behavioral evaluation of PGP-BA-SLNs in depressive rats. (A) The influence of BA-SLNs, PGP-BA-SLNs and BA solution on immobility time; (B) swimming time, (C) climbing time and (D) travelled distance in a forced swim test. Immobility was defined as the minimum movement required to passively keep the animal's head above the water without other motions. Swimming was related to the active behavior of rats to escape from the water. Climbing was defined as upward-directed movements of the forepaws against the wall. The results are expressed as the time that the animals spent immobile during the 5-min test. (E) Locomotor activity of OB rats treated with BA-SLNs, PGP-BA-SLNs and BA solution for 7 days before assay. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, compared with PBS group; #P<0.05, ##P<0.01, compared with BA group.

The behavioral data of rats in the OB model demonstrated a higher level of locomotion, reflected by total travelled distance compared with the sham-saline group (Fig. 5E). BA solution decreased the locomotion of OB rats. PGP-BA-SLNs and BA-SLNs significantly attenuated the hyperactivity of OB rats and both showed a stronger effect than BA solution. Furthermore, the effect of PGP-BA-SLNs was stronger than BA-SLNs. Hence PGP-BA-SLNs exhibited the strongest anti-depressant effect among the three groups.

Another study14 set up both acute and chronic animal models of depression to evaluate the anti-depressant effect of BA. Acute application of BA at doses of 1, 2 and 4 mg/kg by intraperitoneal injection (i.p.) significantly reduced the immobility time in the FST and tail suspending test (TST) of mice. In addition, the chronic application of BA of 1, 2 and 4 mg/kg by i.p. for 21 days also reduced the immobility time and improved locomotor activity in chronic unpredictable mild stress (CMS) model rats. The mechanism involved reversing the reduction of extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) phosphorylation and the level of brain-derived neurotrophic factor expression in the hippocampus of the CMS model rats. It was reported that the chronic administration of BA, including 10, 20, or 40 mg/kg BA (i.p.) 30 min prior to daily exposure to repeated restraint stress (2 h/day) for 14 days decreased depression-like behavior by repeated restraint stress in rats15.

These results suggested that BA produced an antidepressant effect and that this effect was at least partly mediated by hippocampal ERK-mediated neurotrophic action28., 29., 30.. In the present study, PGP-BA-SLNs greatly promoted the anti-depressant effect while the effect of PGP-BA-SLNs were best among those three. Considering the affinity of PGP for neutrophils, this brain-targeting effect and the anti-oxidative effect on the PC 12 cell line, we can believe that brain targeting through the binding of PGP to neutrophils increased the BA concentration in BLA region and enhanced the anti-depressant effect of BA, possibly by an enhanced anti-oxidative effect.

FST is a widely used behavioral model in rodents to assess antidepressant compounds31. The increased immobility time in animals reflects the desperate behavior usually seen in depressed patients. Medications that reduced the immobility time in the FST reflect a potential antidepressant-like activity, such as conventional antidepressant drugs and electroconvulsive therapy. The increased swimming time that the animals spent in the FST indicated the ability to escape actively from stressful events. Therefore, the score of swimming time was another useful indicator for the therapeutic benefits of possible agents in the treatment of depression and stress-related disorder. Inflammation, mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidant-antioxidant imbalance may play a significant role in the development and progression of depression32. The imbalance of oxidant and antioxidant correlates with increased damage to biomolecules, including DNA. 8-Oxoguanine, a marker of oxidative DNA damage, was found in the patients' lymphocytes, urine and serum. Furthermore, it was shown that peroxide-induced DNA damage was less efficiently repaired in the cells of patients than in those from controls. It was reported that inflammasomes are a mediator between psychological and physiological stressors. There is a growing body of evidence indicating that inflammation accompanied by increased oxidative and nitrosative stress may play a crucial role in depression pathogenesis. This stress manifests itself in depressed patients as, for example, increased peroxidation of lipids and elevated production of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (mtROS). The latter may indicate the presence of mitochondrial dysfunction. Moreover, ROS can inflict damage to biomolecules, including DNA. In our nanoparticle–cell system, targeted delivery is based on the inflammatory response and BA is a potent antioxidant. An increased drug concentration could be obtained when the inflammatory response was aggravated, suggesting that oxidant damage is increased. Hence, targeted delivery based on inflammation is a very promising strategy for antioxidant therapy.

4. Conclusions

Taken together, PGP showed a strong binding effect to HL-60 cells and mediated a clear brain targeted delivery in vivo. PGP peptide was believed to be a key chemoattractant in inflammatory disease and plays an important role in neutrophil influx in inflammatory conditions. This interaction between PGP and neutrophils exhibited an excellent targeted delivery with high efficiency. Finally, PGP-SLNs promoted an anti-depressant effect with enhanced BA drug concentration in BLA in a depressed rat model. Hence, the cell–nanoparticle co-delivery system is a promising strategy for a targeted therapy for depression.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful for financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81673372, 81690263, 81361140344 and 81773911), the National Basic Research Program of China (2013CB 932502), the Opening Project of Key Laboratory of Drug Targeting and Drug Delivery System, Ministry of Education (Sichuan University, Chengdu, China) and the Development Project of Shanghai Peak Disciplines–Integrated Medicine (No. 20150407) and the Open Project Program of Key Lab of Smart Drug Delivery (Fudan University, Shanghai, China), Ministry of Education, China.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Chinese Pharmaceutical Association.

Contributor Information

Ning Zhang, Email: ningzh18@126.com.

Huijun Chen, Email: chenhuijun197898@hotmail.com.

Jing Qin, Email: qinjing@fudan.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Chen D., Meng L., Pei F., Zheng Y., Leng J. A review of DNA methylation in depression. J Clin Neurosci. 2017;43:39–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2017.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murray C.J., Lopez A.D. Alternative projections of mortality and disability by cause 1990–2020: global burden of disease study. Lancet. 1997;349:1498–1504. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)07492-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hidaka B.H. Depression as a disease of modernity: explanations for increasing prevalence. J Affect Disord. 2012;140:205–214. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.12.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bakusic J., Schaufeli W., Claes S., Godderis L. Stress, burnout and depression: a systematic review on DNA methylation mechanisms. J Psychosom Res. 2017;92:34–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2016.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klinedinst N.J., Regenold W.T. A mitochondrial bioenergetic basis of depression. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2015;47:155–171. doi: 10.1007/s10863-014-9584-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patel A. Review: the role of inflammation in depression. Psychiatr Danub. 2013;25 Suppl 2:S216–S223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beumer W., Gibney S.M., Drexhage R.C., Pont-Lezica L., Doorduin J., Klein H.C. The immune theory of psychiatric diseases: a key role for activated microglia and circulating monocytes. J Leukoc Biol. 2012;92:959–975. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0212100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pardridge W.M. Drug and gene targeting to the brain with molecular Trojan horses. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2002;1:131–139. doi: 10.1038/nrd725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qin J., Yang X., Zhang R.X., Luo Y.X., Li J.L., Hou J. Monocyte mediated brain targeting delivery of macromolecular drug for the therapy of depression. Nanomedicine. 2015;11:391–400. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2014.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qin J., Yang X., Mi J., Wang J., Hou J., Shen T. Enhanced antidepressant-like effects of the macromolecule trefoil factor 3 by loading into negatively charged liposomes. Int J Nanomed. 2014;9:5247–5257. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S69335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jing Q., Zhang R.X., Li J.L., Wang J.X., Hou J., Yang X. cRGD mediated liposomes enhanced antidepressant-like effects of edaravone in rats. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2014;58:63–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2014.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weathington N.M., van Houwelingen A.H., Noerager B.D., Jackson P.L., Kraneveld A.D., Galin F.S. A novel peptide CXCR ligand derived from extracellular matrix degradation during airway inflammation. Nat Med. 2006;12:317–323. doi: 10.1038/nm1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim S.D., Lee H.Y., Shim J.W., Kim H.J., Yoo Y.H., Park J.S. Activation of CXCR2 by extracellular matrix degradation product acetylated Pro-Gly-Pro has therapeutic effects against sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184:243–251. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201101-0004OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xiong Z., Jiang B., Wu P.F., Tian J., Shi L.L., Gu J. Antidepressant effects of a plant-derived flavonoid baicalein involving extracellular signal-regulated kinases cascade. Biol Pharm Bull. 2011;34:253–259. doi: 10.1248/bpb.34.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee B., Sur B., Park J., Kim S.H., Kwon S., Yeom M. Chronic administration of baicalein decreases depression-like behavior induced by repeated restraint stress in rats. Korean J Physiol Pharmacol. 2013;17:393–403. doi: 10.4196/kjpp.2013.17.5.393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang X., Yang Y., Du L., Zhang W., Du G. Baicalein exerts anti-neuroinflammatory effects to protect against rotenone-induced brain injury in rats. Int Immunopharmacol. 2017;50:38–47. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2017.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chakraborty C., Sarkar B., Hsu C.H., Wen Z.H., Lin C.S., Shieh P.C. Future prospects of nanoparticles on brain targeted drug delivery. J Neurooncol. 2009;93:285–286. doi: 10.1007/s11060-008-9759-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Umezawa F., Eto Y. Liposome targeting to mouse brain: mannose as a recognition marker. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1988;153:1038–1044. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(88)81333-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang C., Ling C.L., Pang L., Wang Q., Liu J.X., Wang B.S. Direct macromolecular drug delivery to cerebral ischemia area using neutrophil-mediated nanoparticles. Theranostics. 2017;7:3260–3275. doi: 10.7150/thno.19979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen C., Duan Z., Yuan Y., Li R., Pang L., Liang J. Peptide-22 and cyclic RGD functionalized liposomes for glioma targeting drug delivery overcoming BBB and BBTB. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2017;9:5864–5873. doi: 10.1021/acsami.6b15831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xu W., Li F., Xu Z., Sun B., Cao J., Liu Y. Tert-butylhydroquinone protects PC12 cells against ferrous sulfate-induced oxidative and inflammatory injury via the Nrf2/ARE pathway. Chem Biol Interact. 2017;273:28–36. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2017.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen Y., Liu L. Modern methods for delivery of drugs across the blood–brain barrier. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2012;64:640–665. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2011.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klinker J.F., Wenzel-Seifert K., Seifert R. G-Protein-coupled receptors in HL-60 human leukemia cells. Gen Pharmacol. 1996;27:33–54. doi: 10.1016/0306-3623(95)00107-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scorrano L., Penzo D., Petronilli V., Pagano F., Bernardi P. Arachidonic acid causes cell death through the mitochondrial permeability transition. Implications for tumor necrosis factor-α apoptotic signaling. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:12035–12040. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010603200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Green D.R., Galluzzi L., Kroemer G. Metabolic control of cell death. Science. 2014;345:1250256. doi: 10.1126/science.1250256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yi E.S., Oh S., Lee J.K., Leem Y.H. Chronic stress-induced dendritic reorganization and abundance of synaptosomal PKA-dependent CP-AMPA receptor in the basolateral amygdala in a mouse model of depression. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2017;6:671–678. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.03.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eckstein M., Markett S., Kendrick K.M., Ditzen B., Liu F., Hurlemann R. Oxytocin differentially alters resting state functional connectivity between amygdala subregions and emotional control networks: inverse correlation with depressive traits. NeuroImage. 2017;149:458–467. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.01.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Czarny P., Wigner P., Galecki P., Sliwinski T. The interplay between inflammation, oxidative stress, DNA damage, DNA repair and mitochondrial dysfunction in depression. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2018;80:309–321. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2017.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Oliveira M.R., Nabavi S.F., Habtemariam S., Erdogan Orhan I., Daglia M., Nabavi S.M. The effects of baicalein and baicalin on mitochondrial function and dynamics: a review. Pharmacol Res. 2015;100:296–308. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2015.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dinda B., Dinda S., DasSharma S., Banik R., Chakraborty A., Dinda M. Therapeutic potentials of baicalin and its aglycone, baicalein against inflammatory disorders. Eur J Med Chem. 2017;131:68–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2017.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anderson G., Maes M. Oxidative/nitrosative stress and immuno-inflammatory pathways in depression: treatment implications. Curr Pharm Des. 2014;20:3812–3847. doi: 10.2174/13816128113196660738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alcocer-Gómez E., de Miguel M., Casas-Barquero N., Núñez-Vasco J., Sánchez-Alcazar J.A., Fernández-Rodríguez A. NLRP3 inflammasome is activated in mononuclear blood cells from patients with major depressive disorder. Brain Behav Immun. 2014;36:111–117. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2013.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]