Abstract

The transforming growth factor-β (TGFβ) pathway plays many key roles in regulating numerous biological processes. In addition, the effects of TGFβ are mediated by the transcription factor Smad3. However, the regulation of Smad3 activity is not well understood. In the present study, quantitative real-time PCR revealed that the Smad3 gene was expressed ubiquitously in 11 bovine tissues and displayed different expression patterns between muscle and adipose tissue. We further explored the expression and regulation of Smad3 gene by cloning the bovine Smad3 gene promoter; a dual-luciferase reporter assay identified that the core promoter region −337 to −41 bp was located in a CpG island. In addition, mutational analyses and electrophoretic mobility shift assays provided evidence that the KLF6, KLF15, MZF1, and KLF7 binding sites within the Smad3 promoter were responsible for the regulation of Smad3 transcription. These findings were confirmed by executing further RNA interference assays in bovine myoblasts and preadipocytes, which indicated that KLF6, KLF15, MZF1, and KLF7 are important transcriptional activators of Smad3 in both adipose and muscle tissue. These results will provide an important basis for an improved understanding of the TGFβ pathway and new insights in cattle breeding.

Keywords: : Smad3, bovine, promoter, myoblasts, preadipocytes

Introduction

The transforming growth factor-β (TGFβ) pathway is involved in a variety of cellular processes, such as cell migration, proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis (Derynck and Feng, 1997; Massague, 2000; Patterson and Padgett, 2000). Several studies have shown that TGFβ is a strong inhibitor of skeletal muscle differentiation (Florini et al., 1986; Massague et al., 1986; Heino and Massague, 1990). More importantly, the Smad transcription factors, which contribute to the termination of TGF signaling and the inhibition of gene expression by blocking the role of transcriptional activators, lie at the core of this pathway (Massague and Wotton, 2000; ten Dijke and Hill, 2004; Feng and Derynck, 2005).

It is worth noting that the Smad2/3 pathway plays a significant role in myostatin and TGFβ signaling in the inhibition of myogenesis. Specifically, Smad3, but not Smad2, is required for the inhibitory effects of TGFβ (Liu et al., 2001, 2004). In addition, the activated Smad3 complexes interact with Smad4 and then translocate to the nucleus to activate/repress the expression of genes. Smad3 is a key mediator of the canonical TGFβ signaling pathway and plays an important role in the TGFβ1-mediated transcriptional regulation of the myogenic differentiation. The specific regulation mechanism is that Smad3 can combine with the basic helix–loop–helix domain of MyoD and block MyoD-E12/47 dimer formation (Liu et al., 2001). It is suggested that the upregulation of Smad3 expression levels can inhibit the expression of muscle regulation factors. In addition to its role in myogenesis, other studies have proved that TGFβ-SMAD3 signaling inhibits adipogenesis in preadipocyte populations (Tsurutani et al., 2011). TGFβ inhibits adipogenesis through Smad3 not Smad2, which interacts with C/EBPs, leading to transcriptional inhibition of the PPARγ2 promoter (Choy and Derynck, 2003). Moreover, Smad3 is necessary for the inhibition of adipogenesis by retinoic acid (Marchildon et al., 2010). In conclusion, the Smad3 gene is a negative regulator in the growth and development of muscle and adipose tissue.

While much is known about the function of Smad3, very little is known about the transcriptional pathways regulating Smad3 expression and the functional consequences of this activation in bovine myoblasts and preadipocytes. In this study, quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) revealed that the Smad3 gene was expressed ubiquitously in 11 bovine tissues. Meanwhile, we found that the Smad3 gene has different expression patterns in the growth and development of muscle and adipose tissues. For a better understanding of bovine Smad3 gene, we analyzed the molecular mechanisms involved in its regulation and found that the transcriptional activity of Smad3 gene was dependent on transcription factors KLF6, KLF15, myeloid zinc finger 1 (MZF1), and KLF7. Therefore, our findings will improve our understanding of the basic transcriptional regulation mechanism and will provide clues for additional investigations of Smad3 gene function in myoblasts and preadipocytes.

Materials and Methods

Ethics statement

All animal experiments were conducted according to the guidelines established by the regulations for Administration of Affairs Concerning Experimental Animals (Ministry of Science and Technology, China, 2004) and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (College of Animal Science and Technology, Northwest A&F University, China) (Protocol NWAFAC1117). The tissues were collected from three 18-month male Qinchuan cattles. Cattles were raised under free food intake and humanely slaughtered in the National Beef Cattle Improvement Center (Yangling, China).

Quantitative real-time PCR

The tissues were collected from three adult Qinchuan cattles, respectively. Total RNA was extracted from the tissues using TRIzol reagent (TaKaRa, Dalian, China) and then reverse transcribed using a PrimeScript™ RT Reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser (Perfect Real Time) (TaKaRa, Dalian, China) and measured using NanoQuant Plate™ (TECAN, Infinite M200PRO). Each real-time (RT) reaction served as template in a 20 μL PCR mixture according to SYBR Premix Ex Taq™ II (TaKaRa, Dalian, China). The reaction mixtures were incubated in the ABI 7500 System (Applied Biosystems). All of the primers used in the qRT-PCR experiment are listed in Table 1. Analytical data were normalized to the mRNA expression level of endogenous control β-actin and GAPDH. The relative expression levels of the target mRNA were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001).

Table 1.

Primer Sequences Utilized in This Study

| Gene name | Accession numbers | Primer sequence (5′>3′) | Binding region | Fragments size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smad3-F1 | NM_001205805 | CGGGGTACCGGCTCTAAACTGGAACGGTCAC | −851/+59 | 910 |

| Smad3-F2 | NM_001205805 | CGGGGTACCGCTGAGTTTCCTGAGTGTGGGTTCC | −608/+59 | 667 |

| Smad3-F3 | NM_001205805 | CGGGGTACCCCGCTGTCCCAGGTCGCCCACGTGG | −445/+59 | 504 |

| Smad3-F4 | NM_001205805 | CGGGGTACCGAGGCGGCAGGGCGCGGGGGAGGAG | −337/+59 | 396 |

| Smad3-F5 | NM_001205805 | CGGGGTACCGGCTGCACGCGGATTTGCATGAAAC | −265/+59 | 324 |

| Smad3-F6 | NM_001205805 | CGGGGTACCCCCGTGCGGAAACCCAAACT | −41/+59 | 100 |

| Smad3-R | NM_001205805 | GAAGATCTAGGCAGTAGCGAAGCGGGAT | ||

| MKLF15–KLF6-F | GGCGGCAGGGCGCGGGAAAGGAGGCGGG | −337/−41 | ||

| MKLF15–KLF6-R | TTCCCGCGCCCTGCCGCCTCCTCCTGCG | −337/−41 | ||

| MKLF7-F | AGTAGGAGCGCGGCGCAAGCCCCGGGCC | −337/−41 | ||

| MKLF7-R | TTGCGCCGCGCTCCTACTCCCGCCCGCT | −337/−41 | ||

| MMZF1-F | GAAGGAGGAGGGCAGCGAGGAGGCGAGG | −337/−41 | ||

| MMZF1-R | TCGCTGCCCTCCTCCTTCCCAGCTCGCT | −337/−41 | ||

| GAPDH-RT-F | NM_001034034 | CCAACGTGTCTGTTGTGGAT | 80 | |

| GAPDH-RT-R | NM_001034034 | CTGCTTCACCACCTTCTTGA | 80 | |

| β-actin-RT-F | NM_173979.3 | CATCGGCAATGAGCGGTTCC | 147 | |

| β-actin-RT-R | NM_173979.3 | ACCGTGTTGGCGTAGAGGTC | 147 | |

| Smad3-RT-F | NM_001205805 | AGCTGACACGGAGGCATATC | 109 | |

| Smad3-RT-R | NM_001205805 | CAGTTGGGAGACTGCACAAA | 109 | |

| KLF6-RT-F | NM_001035271 | AAAGCTCCCACTTGAAAGCA | 146 | |

| KLF6-RT-R | NM_001035271 | TTTAAAAGGCTTGGCACCAG | 146 | |

| KLF15-RT-F | NM_001082425 | AGACCTTCTCGTCGCTGAAA | 145 | |

| KLF15-RT-R | NM_001082425 | GAACACAGGGTTTGCGAGTC | 145 | |

| KLF7-RT-F | NM_001192919 | CTCATGGGAAGGGTGTGAGT | 119 | |

| KLF7-RT-R | NM_001192919 | ACCTGGAAAAACACCTGTCG | 119 | |

| MZF1-RT-F | NM_001206304 | CCCAGGGTTTACACTCCAGA | 144 | |

| MZF1-RT-R | NM_001206304 | GCTTGTGAAAAGCCACCTTC | 144 | |

| KLF15–KLF6-EMSA-F | GAGGCGGCAGGGCGCGGGGGAGGAGGCGGGGAGCC | |||

| KLF15–KLF6-EMSA-R | GGCTCCCCGCCTCCTCCCCCGCGCCCTGCCGCCTC | |||

| MKLF15–KLF6-EMSA-F | GAGGCGGCAGGGCGCGAGAAAGGAGGCGGGGAGCC | |||

| MKLF15–KLF6-EMSA-R | GGCTCCCCGCCTCCTTTCTCGCGCCCTGCCGCCTC | |||

| KLF7-EMSA-F | TAGGAGCGCGGCGCACGCCCCGGGCCGGCCCAGC | |||

| KLF7-EMSA-R | GCTGGGCCGGCCCGGGGCGTGCGCCGCGCTCCTA | |||

| MKLF7-EMSA-F | TAGGAGCGCGGCGCACGCACCGGGCCGGCCCAGC | |||

| MKLF7-EMSA-R | GCTGGGCCGGCCCGGTGCGTGCGCCGCGCTCCTA | |||

| MZF1-EMSA-F | AAGGAGGAGGGCAGCGGGGAGGCGAGGCTGCCGA | |||

| MZF1-EMSA-R | TCGGCAGCCTCGCCTCCCCGCTGCCCTCCTCCTT | |||

| MMZF1-EMSA-F | AAGGAGGAGGGCAGCGAGGAGGCGAGGCTGCCGA | |||

| MMZF1-EMSA-R | TCGGCAGCCTCGCCTCCTCGCTGCCCTCCTCCTT | |||

| siRNA-KLF6-F | NM_001035271 | GCAAGAAGCGAUGAGUUAATT | ||

| siRNA-KLF6-R | NM_001035271 | UUAACUCAUCGCUUCUUGCTT | ||

| siRNA-KLF15-F | NM_001082425 | GACCUUCUCGUCGCUGAAATT | ||

| siRNA-KLF15-R | NM_001082425 | UUUCAGCGACGAGAAGGUCTT | ||

| siRNA-KLF7-F | NM_001192919 | GCCUUGAAUUGGAACGCUATT | ||

| siRNA-KLF7-R | NM_001192919 | UAGCGUUCCAAUUCAAGGCTT | ||

| siRNA-MZF1-F | NM_001206304 | CCAGAGCACCAAGCUCAUUTT | ||

| siRNA-MZF1-F | NM_001206304 | AAUGAGCUUGGUGCUCUGGTT |

Underlines indicate base mutations.

Plasmid construction

The bovine Smad3 gene promoter covering a region from −851 to +59 bp (910 bp, define the transcription start site [TSS] as +1) was amplified from cattle genomic DNA by PCR and ligated into the pGL3-basic vector digested with KpnI and XhoI restriction enzymes. A series of 5′ deletion constructs of the bovine Smad3 promoter (−851/+59 [910 bp], −608/+59 [667 bp], −337/+59 [396 bp], −265/+59 [324 bp], −120/+59 [179 bp], and −41/+59 [100 bp]) were prepared. Fragment primers were designed as shown in Table 1.

Mutation constructs were produced by a Fast Mutagenesis System (TransGene, Beijing, China). The MatInspector program available online at www.genomatix.de was used to analyze putative transcription factor binding sites on the positive and negative chain of the Smad3 promoter and ensure that the site-directed mutagenesis did not produce any new binding sites for transcription factors.

Cell culture, transfection, and dual-luciferase reporter assay

Bovine myoblasts (Blanton et al., 1999; Hindi et al., 2017) and preadipocytes (Bunnell et al., 2008; Ren et al., 2012) were isolated from the longissimus thoracis muscle and subcutaneous fat following a previously described method with minor modifications. Longissimus thoracis samples were collected from the back of the longissimus thoracis muscle between vertebrae 9 and 10, and subcutaneous adipose tissues were collected from abdominal subcutaneous adipose tissue. Myoblasts were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM/F12; HyClone) supplemented with 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco), but preadipocytes were cultured in F12 supplemented with 10% FBS. When the cells achieved 80–90% confluence, they were passaged by trypsinization. Cells were plated at a density of 1.2 × 105 cells/well in 24-well dishes, and 24 h later, they were transfected with the plasmids described above using X-tremeGENE HP DNA Transfection Reagent (Roche) according to the manufacturer's instructions (Li et al., 2015). The experiments were performed in triplicate for each construct. The luciferase activity of transfected cells was measured according to the instructions.

The methylation CpG island of bovine Smad3 promoter was analyzed at www.urogene.org/cgi-bin/methprimer/methprimer.cgi All constructs were sequenced in both directions (Jinsirui, Nanjing, China).

RNA interference

All siRNAs were designed and synthesized according to the online prediction program at http://rnaidesigner.thermofisher.com/rnaiexpress KLF6-siRNA, KLF15-siRNA, KLF7-siRNA, and MZF1-siRNA sequences are shown in Table 1; siRNAs were then transfected into bovine myoblasts and preadipocytes with Lipofectamine™ 3000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. siRNAs (20 μM) were transfected as 100 pmol mixed with 5 μL Lipofectamine 3000 per six wells. At 48 h after transfection, the cells were lysed, and the expressions were measured by qRT-PCR described as above.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays

Nuclear extracts from myoblasts and preadipocytes were prepared using the Nuclear Extract Kit (Active Motif Corp, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The protein concentration in the nuclear fraction was determined using the Bradford dye assay (Bio-Rad Corp, Richmond, CA). All of the DNA probes used in the electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) (listed in Table 1) were synthesized (Invitrogen) and labeled at the 5′ end with biotin. The specific experimental steps refer to the previously described method with minor modifications (Zhao et al., 2016); 400 fmol of the labeled probes were added, and for the supershift assay, 10 μg each of KLF6, KLF15, MZF1, and KLF7 (Sangon, China) antibody was added. Finally, the main complexes were resolved by electrophoresis in 6.5% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis using 0.5 × TBE buffer for 1 h, and then, images were captured with ChemiDoc™ XRS+ System molecular image (Bio-Rad).

Statistical analyses

A one-way analysis of variance test was conducted to determine the significance level. Mean values were compared by the least significant difference post-test using the SPSS 17.0 program. The results are expressed as the mean ± SD, and the p < 0.05 (*), p < 0.01 (**), and p < 0.001 (***) were considered to be statistically significant, very significant, and extremely significant in all statistical analyses, respectively.

Results

Detection of Smad3 expression in bovine tissues and organs

TGFβ-SMAD3 signaling is involved in a variety of biological processes. To enhance our understanding of the transcriptional regulation mechanism of Smad3 in various tissues of Qinchuan cattle, we investigated the expression profiles of Smad3 in different tissues through qRT-PCR. cDNA was collected from 11 bovine tissues and organs, as shown in Figure 1A, and qRT-PCR analysis demonstrated that Smad3 was expressed ubiquitously in bovine tissues and organs. Significantly high transcript levels were observed in omasum, rumen, and longissimus thoracis. Kidney, large intestine, heart, lung, subcutaneous adipose, and liver displayed moderate transcript levels, and the spleen had the lowest transcript level. Previous studies have shown that the Smad3 gene plays an important role in the growth and development of fat and muscle, and in the present study, we found that the mRNA of Smad3 expression is different in the Longissimus dorsi and subcutaneous adipose tissue. The expression of the bovine Smad3 gene in longissimus thoracis continuously declines from 0 to 60 months after birth (Fig. 1B). However, the expression of the bovine Smad3 gene rises in subcutaneous adipose from 0 to 12 months of age and then falls until 60 months of age (Fig. 1C).

FIG. 1.

Tissue expression distribution of Smad3 gene. (A) Relative expression pattern analysis of Smad3 in different bovine tissues and organs was detected by quantitative real-time PCR. Results were normalized to the geometric mean of the two suitable housekeeping genes (GAPDH and β-actin) and expressed relative to gene expression in the spleen group. (B) Expression pattern analysis of bovine Smad3 gene in different stage longissimus dorsi and expressed relative to 0 month. (C) Expression pattern analysis of bovine Smad3 gene in different stage subcutaneous adipose and expressed relative to 0 month. Each column value represents the mean ± standard deviation based on three independent experiments. The error bars denote the standard deviations. ***p < 0.001.

Identification of the core promoter region

We first identified the core promoter region of the Smad3 gene to find its key transcription factors. A 910 bp fragment of the bovine Smad3 gene 5′-flanking sequence spanning nucleotides from −851 to +59 bp was amplified, and the sequence was identical to that in the GenBank database (Accession no. AC_000167.1). Six serial deletion constructs in pGL3-basic containing (−851/+59 [910 bp], −608/+59 [667 bp], −337/+59 [396 bp], −265/+59 [324 bp], −120/+59 [179 bp], and −41/+59 [100 bp]) were generated to narrow down the core region of bovine Smad3 promoter and were then cotransfected with pRL-TK plasmid into bovine myoblasts and preadiocytes for dual-luciferase reporter assay (Fig. 2A, B). Significantly higher promoter activity was observed in myoblasts containing the region between −337 and −41 bp relative to TSS +1 than those containing the other regions, which indicated that this fragment contained the core region of the bovine Smad3 promoter and probably interacts with important transcriptional factors. The same results were obtained in preadipocytes. Therefore, the core promoter region of Smad3 was located at −337 and −411 bp relative to TSS +1.

FIG. 2.

The Smad3 gene promoter was analyzed by computational analyses together with luciferase reporter system. A series of plasmids containing 5′ unidirectional deletions of the promoter region of the Smad3 gene (−851/+59 [910 bp], −608/+59 [667 bp], −337/+59 [396 bp], −265/+59 [324 bp], −120/+59 [179 bp], −41/+59 [100 bp], and pGL3-basic) fused in frame to luciferase gene were transfected into myoblasts (A, B) and preadipocytes. After 48 h, the cells were harvested for luciferase assay. Results are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation in arbitrary units based on the firefly luciferase activity normalized against the Renilla luciferase activity for triplicate transfections. The error bars denote the standard deviation. **p < 0.01. The data shown are representative of two independent experiments. Positions −337 to −41 bp in the promoter are also shown.

Sequence analyses of the bovine Smad3 gene promoter

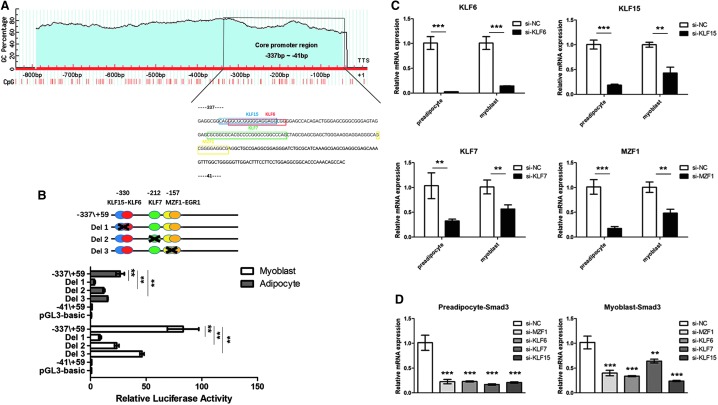

Despite the important role of Smad3 in regulating the formation of muscle and fat, there is limited information regarding the transcriptional regulation of bovine Smad3. Utilizing the MatInspector program (Genomatix), we analyzed the cloned promoter fragment consisting of 910 bp upstream of TSS. An analysis was performed to identify regulatory elements in promoter core region with a cutoff value over 85%. We identified four important transcription factor recognition sites for KLF6, KLF7, MZF1, and KLF15. In addition, neither a TATA box nor a CAAT box was identified at the upstream of TSS using Promoter Scan. However, this region was found to be GC-rich. The online program MethPrimer revealed one predicted CpG island within the promoter region of the bovine Smad3, and the core promoter of bovine Smad3 gene was located at the CpG island (Fig. 3A). Site-directed mutagenesis was carried out in the construct pGL −337/+59 (Fig. 3B). Further cotransfection of siRNAs against KLF15, KLF6, MZF1, and KLF7 led to significant decrease in Smad3 gene expression (p < 0.001) (Fig. 3C, D) both in myoblasts and preadipocytes. In conclusion, KLF15, KLF6, MZF1, and KLF7 may regulate the mRNA expression of Smad3 gene as transcriptional activators.

FIG. 3.

Analysis of KLF15–KLF6, KLF7, and MZF1 binding sites by site-directed mutagenesis and the predicted CpG island in the proximal Smad3 promoter. (A) Sequence and putative transcription factor-binding sites of the proximal minimal promoter of Smad3 gene. Putative transcription factor binding sites are boxed: blue box, KLF15; red box, KLF6; green box, KLF7; yellow box, MZF1. The CpG island is indicated by a blue area. (B) Site-directed mutagenesis was carried out in the construct pGL −337/+59. The different constructs were transiently transfected into myoblasts and preadipocytes. (C, D) siRNA regulates the expression of Smad3 relative to siRNA-NC. Each column value represents the mean ± standard deviation based on three independent experiments. The error bars denote the standard deviations. **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001.

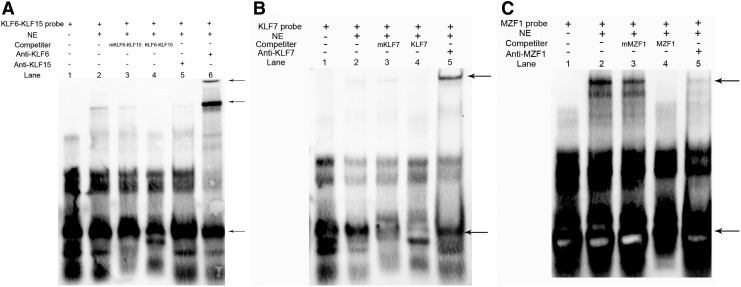

KLF15, KLF6, MZF1, and KLF7 bind to the core promoter region of Smad3 gene as transcriptional activators in vitro

EMSA were used to confirm whether KLF15, KLF6, MZF1, and KLF7 bind to the Smad3 gene promoter in vitro, and the results are shown in Figure 4. The nuclear protein from myoblasts and preadipocytes bound to the 5′-biotin labeled KLF15, KLF6, MZF1, and KLF7 probes and formed the main complexes (lane 2, Figure 4A–C). Competition assays verified the specificity of the KLF15/DNA, KLF6/DNA, MZF1/DNA, and KLF7/DNA interaction (lanes 3, Fig. 4A–C), whereas the mutant probe had a small effect on the main complexes (lanes 4, Fig. 4A–C). The last lane shows that the complex was supershifted when it was incubated with antibody (lane5, A). These results indicated that KLF15, KLF6, MZF1, and KLF7 bind to the core promoter region of the Smad3 gene as transcriptional activators in vitro.

FIG. 4.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays showing KLF15–KLF6, KLF7, and MZF1 direct binding of Smad3 promoter in vitro. The main complexes are marked with arrows. (A) Nuclear protein extracts were incubated with free probe KLF15–KLF6 containing the binding site in the presence of 10× unlabeled probe (lane 3), 10× mutation probe (lane 4), in the absence of any competitor (lane 2). The supershift assay was conducted using 10 ng anti-antibody (lane 6). (B) Nuclear protein extracts were incubated with free probe KLF7 containing the binding site in the presence of 10× unlabeled probe (lane 3) and 10× mutation probe (lane 4), in the absence of any competitor (lane 2). The assay was conducted using 10 ng anti- antibody (lane 5). (C) Nuclear protein extracts were incubated with free probe MZF1 containing the binding site in the presence of 10× unlabeled probe (lane 3) and 10× mutation probe (lane 4), in the absence of any competitor (lane 2). The assay was conducted using 10 ng anti-antibodies (lane 5).

Discussion

The regulation of skeletal muscle development requires many of the regulatory networks that are fundamental to developmental myogenesis. It has been shown that TGFβ superfamily blocks muscle differentiation (Trendelenburg et al., 2009). TGFβ and myostatin rely on canonical Smad signaling, especially Smad2/3, to elicit biological functions during myogenesis (Langley et al., 2002; Liu et al., 2004). Previous research has also suggested that knockdown of SMAD2/3 by siRNA was shown to induce differentiation (Sartori et al., 2009). Moreover, Smad3 is a key signaling molecule/transcription factor for normal skeletal muscle growth, and a lack of Smad3 severely affects myogenesis (Ge et al., 2011). Studies on the Smad3 gene have mainly focused on its regulation of muscle growth and development, and many recent studies have shown that it is also involved in the regulation of adipocyte differentiation. The process of adipocyte differentiation is driven by a highly coordinated cascade of transcriptional events. Several studies have shown that TGFβ inhibited adipocyte differentiation. Similarly, in myoblast differentiation, Smad3, and not Smad2, mediates the inhibition of adipocyte differentiation by TGFβ and myostatin (Kim et al., 2001; Hirai et al., 2007). We investigated the function of Smad3 gene in the development of bovine muscle and adipose tissue by examining the expression profile of bovine Smad3 gene. In addition, we found that Smad3 mRNAs are ubiquitously expressed, but that their ratios vary across different tissues in different stages. However, the Smad3 gene was expressed at a high level in bovine longissimus dorsi (Fig. 1A). In addition, we detected a declining trend in the Smad3 gene expression in bovine longissimus dorsi from 0 to 60 months after birth (Fig. 1B). In contrast, the expression of the bovine Smad3 gene increased in subcutaneous adipose from 0 to 12 months of age and then it fell. The age of 0–6 months is also known as the calf stage, which is an important stage in which muscles grow and develop rapidly. According to previous research, the Smad3 gene is a strong inhibitor of the process of myoblast differentiation (Liu et al., 2004; Ge et al., 2011), and a decrease in Smad3 gene expression also means that the function of the TGFβ signaling pathway is weakened, which promotes the growth and development of muscle at the age of 0–6 months. However, currently, only a handful of studies have shown that Smad3 is a key gene in the signaling pathway that inhibits fat growth and development. The role of Smad3 in fat growth and development remains to be studied. Therefore, the expression of Smad3 mRNA is different in longissimus dorsi and subcutaneous adipose tissue.

In addition, the transcription factors that contribute to the control and regulation of Smad3 expression in cattle myoblasts and preadipocyte differentiation have not been characterized. Previous studies have shown that Smad3 expression is suppressed in a way that is dependent on sp1/sp3 (Lee et al., 2004), and mitogen-activated protein kinase A activity can stimulate Smad3 expression by inhibiting Sp1 binding to a region between −849 and −408 of the Smad3 promoter (Ross et al., 2007). ETS1 and TFAP2A are major transcription factors that regulate the function of Smad2/3 (Koinuma et al., 2009). In our study, the −337 to −41 bp core promoter region of the Smad3 gene was identified by the deletion located on a CpG island. Bioinformatic analysis and experiments revealed some important cis element binding sites, including KLF6, KLF15, KLF7, and MZF1. Furthermore, our current study demonstrated the core promoter motifs and key regulators controlling the transcription of bovine Smad3 gene by luciferase reporter system (Fig. 3A, B) EMSA (Fig. 4). Kruppel-like factors (KLFs) are members of the zinc-finger class of DNA-binding transcription factors (Haldar et al., 2007; Prosdocimo et al., 2015). KLFs bind a consensus 5′-C(A/T)CCC-3′ motif in the promoters and enhancers of various genes. (Black et al., 2001; Wang et al., 2008; Nagare et al., 2009). Previously, it was reported that KLFs are critical molecules in both the promotion and inhibition of adipocyte differentiation. KLF6 and KLF15 promote adipogenesis, whereas KLF7 inhibits adipogenesis (Wu and Wang, 2013). Despite the early identification of KLFs nearly two decades ago, the role of KLFs in skeletal muscle has until recently been understudied compared to its role in cardiac and smooth muscle. KLF6 has been recently considered as a downstream effector of TGFβ and a molecular regulator of skeletal myoblast proliferation (Dionyssiou et al., 2013). In addition, KLF15 is a key determinant of skeletal muscle lipid flux and motor ability (Haldar et al., 2012). However, there have been no studies on KLF7 in skeletal muscle development. MZF1 is a bifunctional transcription factor that can act as both a transcriptional repressor and activator in many biological processes (Eguchi et al., 2015). Although many reports proved that KLF15, KLF6, and KLF7 have the opposite effect on the development of skeletal muscle and adipose tissues, in the present study, we confirmed that KLF6, KLF15, and KLF7 can activate the transcription of bovine Smad3 individually and that they exhibited equal effects on promoter activities despite the fact that the Smad3 gene inhibits myogenesis and adipogenesis. For verification of these results, we designed siRNAs to interfere with KLF6, KLF15, MZF1, and KLF7 in bovine myoblasts and preadipocytes, and our results were in line with previous findings (Fig. 3C, D). Collectively, these results suggest a model demonstrating the biological role of Smad3 in myogenesis and adipogenesis (Fig. 5). In the proposed model, Smad3 inhibits both myogenesis and adipogenesis. KLF6 and KLF15 promote the differentiation of myoblasts and preadipocytes, but suppress the expression and activity of Smad3, and KLF7 and MZF1 also act as activators. We hypothesized that KLF6 and KLF15 may differ in their regulation of myogenesis and adipogenesis due to species differences. Therefore, the interaction between these genes requires further studies.

FIG. 5.

A proposed model of the biological role of Smad3 in myogenesis and adipogenesis.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we determined the core promoter region and the transcription regulators affecting Smad3 transcription. For the first time, the transcriptional factors KLF6, KLF15, MZF1, and KLF7 were found to transactivate Smad3 gene expression by binding to the core promoter region. The present study will improve our understanding of the basic transcriptional regulation mechanism and will provide clues for further investigations of Smad3 gene function. Moreover, these results can ultimately provide insights for studies on bovine muscle and fat development.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National 863 Program of China (No. 2013AA102505), National Science-Technology Support Plan Projects (No. 2015BAD03B04), and National Beef and Yak Industrial Technology System (No. CARS-37). The authors thank all the research assistants and laboratory technicians who contributed to this work.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- Black A.R., Black J.D., and Azizkhan-Clifford J. (2001). Sp1 and kruppel-like factor family of transcription factors in cell growth regulation and cancer. J Cell Physiol 188, 143–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanton J.R., Jr, Grant A.L., McFarland D.C., Robinson J.P., and Bidwell C.A. (1999). Isolation of two populations of myoblasts from porcine skeletal muscle. Muscle Nerve 22, 43–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunnell B.A., Flaat M., Gagliardi C., Patel B., and Ripoll C. (2008). Adipose-derived stem cells: isolation, expansion and differentiation. Methods 45, 115–120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choy L., and Derynck R. (2003). Transforming growth factor-beta inhibits adipocyte differentiation by Smad3 interacting with CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein (C/EBP) and repressing C/EBP transactivation function. J Biol Chem 278, 9609–9619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derynck R., and Feng X.H. (1997). TGF-beta receptor signaling. Biochim Biophys Acta 1333, F105–F150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dionyssiou M.G., Salma J., Bevzyuk M., Wales S., Zakharyan L., and McDermott J.C. (2013). Kruppel-like factor 6 (KLF6) promotes cell proliferation in skeletal myoblasts in response to TGFbeta/Smad3 signaling. Skelet Muscle 3, 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eguchi T., Prince T., Wegiel B., and Calderwood S.K. (2015). Role and regulation of myeloid zinc finger protein 1 in cancer. J Cell Biochem 116, 2146–2154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng X.H., and Derynck R. (2005). Specificity and versatility in tgf-beta signaling through Smads. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 21, 659–693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florini J.R., Roberts A.B., Ewton D.Z., Falen S.L., Flanders K.C., and Sporn M.B. (1986). Transforming growth factor-beta. A very potent inhibitor of myoblast differentiation, identical to the differentiation inhibitor secreted by Buffalo rat liver cells. J Biol Chem 261, 16509–16513 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge X., McFarlane C., Vajjala A., Lokireddy S., Ng Z.H., Tan C.K., et al. (2011). Smad3 signaling is required for satellite cell function and myogenic differentiation of myoblasts. Cell Res 21, 1591–1604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haldar S.M., Ibrahim O.A., and Jain M.K. (2007). Kruppel-like Factors (KLFs) in muscle biology. J Mol Cell Cardiol 43, 1–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haldar S.M., Jeyaraj D., Anand P., Zhu H., Lu Y., Prosdocimo D.A., et al. (2012). Kruppel-like factor 15 regulates skeletal muscle lipid flux and exercise adaptation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109, 6739–6744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heino J., and Massague J. (1990). Cell adhesion to collagen and decreased myogenic gene expression implicated in the control of myogenesis by transforming growth factor beta. J Biol Chem 265, 10181–10184 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hindi L., McMillan J.D., Afroze D., Hindi S.M., and Kumar A. (2017). Isolation, culturing, and differentiation of primary myoblasts from skeletal muscle of adult mice. Bio Protoc 7, e2248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirai S., Matsumoto H., Hino N., Kawachi H., Matsui T., and Yano H. (2007). Myostatin inhibits differentiation of bovine preadipocyte. Domest Anim Endocrinol 32, 1–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H.S., Liang L., Dean R.G., Hausman D.B., Hartzell D.L., and Baile C.A. (2001). Inhibition of preadipocyte differentiation by myostatin treatment in 3T3-L1 cultures. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 281, 902–906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koinuma D., Tsutsumi S., Kamimura N., Taniguchi H., Miyazawa K., Sunamura M., et al. (2009). Chromatin immunoprecipitation on microarray analysis of Smad2/3 binding sites reveals roles of ETS1 and TFAP2A in transforming growth factor beta signaling. Mol Cell Biol 29, 172–186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langley B., Thomas M., Bishop A., Sharma M., Gilmour S., and Kambadur R. (2002). Myostatin inhibits myoblast differentiation by down-regulating MyoD expression. J Biol Chem 277, 49831–49840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J.Y., Elmer H.L., Ross K.R., and Kelley T.J. (2004). Isoprenoid-mediated control of SMAD3 expression in a cultured model of cystic fibrosis epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 31, 234–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li A., Zhao Z., Zhang Y., Fu C., Wang M., and Zan L. (2015). Tissue expression analysis, cloning, and characterization of the 5′-regulatory region of the bovine fatty acid binding protein 4 gene. J Anim Sci 93, 5144–5152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D., Black B.L., and Derynck R. (2001). TGF-beta inhibits muscle differentiation through functional repression of myogenic transcription factors by Smad3. Genes Dev 15, 2950–2966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D., Kang J.S., and Derynck R. (2004). TGF-beta-activated Smad3 represses MEF2-dependent transcription in myogenic differentiation. EMBO J 23, 1557–1566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak K.J., and Schmittgen T.D. (2001). Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 25, 402–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchildon F., St-Louis C., Akter R., Roodman V., and Wiper-Bergeron N.L. (2010). Transcription factor Smad3 is required for the inhibition of adipogenesis by retinoic acid. J Biol Chem 285, 13274–13284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massague J. (2000). How cells read TGF-beta signals. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 1, 169–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massague J., Cheifetz S., Endo T., and Nadal-Ginard B. (1986). Type beta transforming growth factor is an inhibitor of myogenic differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 83, 8206–8210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massague J., and Wotton D. (2000). Transcriptional control by the TGF-beta/Smad signaling system. EMBO J 19, 1745–1754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagare T., Sakaue H., Takashima M., Takahashi K., Gomi H., Matsuki Y., et al. (2009). The Kruppel-like factor KLF15 inhibits transcription of the adrenomedullin gene in adipocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 379, 98–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson G.I., and Padgett R.W. (2000). TGF beta-related pathways. Roles in Caenorhabditis elegans development. Trends Genet 16, 27–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prosdocimo D.A., Sabeh M.K., and Jain M.K. (2015). Kruppel-like factors in muscle health and disease. Trends Cardiovasc Med 25, 278–287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren Y., Wu H., Zhou X., Wen J., Jin M., Cang M., et al. (2012). Isolation, expansion, and differentiation of goat adipose-derived stem cells. Res Vet Sci 93, 404–411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross K.R., Corey D.A., Dunn J.M., and Kelley T.J. (2007). SMAD3 expression is regulated by mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase-1 in epithelial and smooth muscle cells. Cell Signal 19, 923–931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sartori R., Milan G., Patron M., Mammucari C., Blaauw B., Abraham R., et al. (2009). Smad2 and 3 transcription factors control muscle mass in adulthood. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 296, C1248–C1257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ten Dijke P., and Hill C.S. (2004). New insights into TGF-beta-Smad signalling. Trends Biochem Sci 29, 265–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trendelenburg A.U., Meyer A., Rohner D., Boyle J., Hatakeyama S., and Glass D.J. (2009). Myostatin reduces Akt/TORC1/p70S6K signaling, inhibiting myoblast differentiation and myotube size. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 296, C1258–C1270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsurutani Y., Fujimoto M., Takemoto M., Irisuna H., Koshizaka M., Onishi S., et al. (2011). The roles of transforming growth factor-beta and Smad3 signaling in adipocyte differentiation and obesity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 407, 68–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B., Haldar S.M., Lu Y., Ibrahim O.A., Fisch S., Gray S., et al. (2008). The Kruppel-like factor KLF15 inhibits connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) expression in cardiac fibroblasts. J Mol Cell Cardiol 45, 193–197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z., and Wang S. (2013). Role of kruppel-like transcription factors in adipogenesis. Dev Biol 373, 235–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Z.D., Zan L.S., Li A.N., Cheng G., Li S.J., Zhang Y.R., et al. (2016). Characterization of the promoter region of the bovine long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase 1 gene: roles of E2F1, Sp1, KLF15, and E2F4. Sci Rep 6, 19661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]