Abstract

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) the deadliest form of this disease currently lacks a targeted therapy and is characterized by increased risk of metastasis and presence of therapeutically resistant cancer stem cells (CSC). Recent evidence has demonstrated that the presence of an interferon (IFN)/signal transducer of activated transcription 1 (STAT1) gene signature correlates with improved therapeutic response and overall survival in TNBC patients. In agreement with these clinical observations, our recent work has demonstrated, in a cell model of TNBC that CSC have intrinsically repressed IFN signaling. Administration of IFN-β represses CSC properties, inducing a less aggressive non-CSC state. Moreover, an elevated IFN-β gene signature correlated with repressed CSC-related genes and an increased presence of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in TNBC specimens. We therefore propose that IFN-β be considered as a potential therapeutic option in the treatment of TNBC, to repress the CSC properties responsible for therapy failure. Future studies aim to improve methods to target delivery of IFN-β to tumors, to maximize therapeutic efficacy while minimizing systemic side effects.

Keywords: : interferon-beta, triple-negative breast cancer, cancer stem cells

Introduction

Triple-Negative Breast Cancer (TNBC) is the deadliest form of breast cancer and is characterized by elevated risk of metastasis and tumor recurrence. Defined by its lack of expression of estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and HER2 amplification (HER2), TNBC currently lacks a targeted therapy and therefore, chemotherapy and radiation remain the standard of care (Burstein et al., 2015; Yu et al., 2017). Unfortunately, despite early, initial responses to therapy, the majority of TNBC tumors relapse and metastasize. In this article, we discuss our recent studies which suggest that interferon-beta (IFN-β) signaling regulates the differentiation status of cancer cells, and propose new strategies for using IFN-β as a therapy to minimize TNBC metastasis and therapy failure.

The IFNs are a class of immune cytokines originally identified for their ability to successfully “interfere” or disrupt viral and bacterial replication within an infected cell as part of a critical immune surveillance response to clear host infections. The type 1 IFNs (IFN-α and IFN-β) have been extensively studied for their ability to repress tumor cell proliferation through proapoptotic/cytotoxic programs (Porritt and Hertzog, 2015; Parker et al., 2016). Type I IFNs induce phosphorylation of an IFN-stimulated gene factor 3 (P-ISGF3) transcription factor complex (consisting of signal transducer of activated transcription 1 [STAT1], STAT2, and IRF9), which drives the expression of hundreds of interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs). Importantly, the STAT1, STAT2, and IRF9 genes are transcriptional targets of P-ISGF3, resulting in large increases in unphosphorylated ISGF3 (U-ISGF3) complexes. The U-ISGF3 complexes drive the expression of a subset of P-ISGF3 genes, many of which can have protumorigenic effects and induce resistance to DNA damage (Weichselbaum et al., 2008; Cheon et al., 2013). The balance of P-ISGF3 and U-ISGF3 signaling appears to be a major determinant of biological outcome, likely explaining the less-than-impressive clinical activity of type I IFNs in some tumor types. Likewise, there appear to be tissue- and tumor-specific effects of IFNs.

In TNBC, recent DNA/RNA profiling identified an immune-active subtype characterized by an elevated IFN/STAT1 signature and presence of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs). These “HOT” tumors often respond better to therapy, resulting in an improved prognosis when compared with an immune-repressed subtype lacking IFN/STAT1 and TILs (“COLD” tumors) (Yang et al., 2014; Burstein et al., 2015). In another study, an endogenous IFN signature predicted an increased sensitivity to Adriamycin in matched tumors compared before and after treatment (Sistigu et al., 2014). Similarly, IFN signaling was correlated with decreased incidence of metastasis in several breast cancer patient datasets in addition to being an important determinant of therapeutic response (Bidwell et al., 2012; Slaney et al., 2013). Finally, we recently identified an IFN-β gene signature, developed from transformed Human Mammary Epithelial Cells treated with IFN-β. Cells with elevated expression of our IFN-β gene signature harbored reduced cancer stem cell (CSC) properties, and reduced migratory capacity. When examined in TNBC specimens, our IFN-β gene signature correlated with a repressed CSC gene signature, increased TILs, and ultimately improved patient survival. Moreover, we found that CSC treated with exogenous IFN-β acquired a more differentiated, epithelial phenotype associated with repression of Vimentin and SLUG and elevated expression of CD24, indicating that the cells had undergone a mesenchymal–epithelial transition often associated with less aggressive, non-CSC (Doherty et al., 2017).

Interestingly, previously published work demonstrated a similar finding when using acute, high doses of IFN-α to treat chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML). Essers et al. (2009) found that treatment with IFN-α in vivo induced CML-hematopoietic stem cells (HSC) to differentiate from a stem to nonstem state. Interestingly, IFN-α sensitized CML-HSC to 5-fluoruracil, demonstrating that IFN signaling can drive tumor cells from their therapy-resistant CSC state into a therapy-sensitive non-CSC state. Taken together, these findings suggest that type I IFNs play a critical role in regulating the stem-differentiation continuum that determines therapeutic outcome.

IFNβ as a CSC-Targeted Therapy for TNBC: New Therapeutic Strategies

While IFNs have been used successfully to treat hematological malignancies and some solid tumors (melanoma), the use of IFN in other tumor types has been a challenge (Essers et al., 2009; Parker et al., 2016). High doses of IFN can repress tumor cell–intrinsic proliferation and induce cell death, both in vitro using cancer cell lines as well as in vivo using patient-derived tumor cells (Essers et al., 2009; Parker et al., 2016; Brockwell et al., 2017). In the clinic, however, high-dose treatment with IFN results in many side effects, including malaise, flu-like symptoms (muscle aches, fever, fatigue), nausea, depression, and leukopenia that have limited its use. In our studies, nontoxic and noncytostatic doses of IFN-β were sufficient to repress aggressive TNBC properties (tumor sphere formation, migratory capacity Stem/EMT markers; Slug and Vimentin, respectively), as well as restore non-CSC surface marker expression (CD24) (Doherty et al., 2017). Our work therefore provides a rationale for using low-dose IFN-β to specifically target CSC responsible for therapy failure. Likewise, since metastatic outgrowth is the primary cause of patient mortality in TNBC, it may be valuable to stratify for patients who present with high risk of metastasis and therefore would potentially benefit from IFN-β therapy.

Another method for ensuring the maximal efficacy and minimal toxicity of IFN-β treatment is to target its delivery to the tumor. For example, prior studies demonstrated that mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) engineered to express IFN-β (MSC-IFN-β) migrated to sites of established, highly aggressive, and metastatic 4T1 murine primary breast tumors. Importantly, IFN-β not only repressed primary tumor growth, but also significantly reduced both pulmonary and hepatic metastases relative to control MSC. Mechanistically, IFN-β repressed constitutive phosphorylation of STAT3, Src, and AKT and helped retain presence of dendritic cells and CD8+ T cells, components of innate and adaptive immunity, respectively (Ling et al., 2010). Perhaps more feasible is the use of targeted monoclonal antibodies to tumor cell-specific antigens. For example, intratumoral administration of an EGFR-targeting antibody conjugated with IFN-β (anti-EGFR-IFNβ) improved therapeutic response by inducing dendritic cells to increase antigen presentation to cytotoxic T-lymphocytes (Yang et al., 2014).

A relatively new targeting approach involves the use of nanobodies. Nanobodies are comprised of a single peptide chain of ∼110 amino acids and exhibit similar affinity to antigens when compared with standard antibodies (Steeland et al., 2016). However, nanobodies are heat, detergent, and urea resistant, have superior solubility, and penetrate deeper and more homogenously into tumor tissue relative to standard, larger antibodies. Most importantly, because nanobodies are encoded by single exons, they can be cloned, manipulated, and easily produced in bulk (Steeland et al., 2016; Hu et al., 2017). Previous work utilized a nanobody (nb) targeting the mouse PD-L2 cell surface protein fused with a modified IFN-α. The PD-L2nb-IFN-α conjugate was significantly enriched in PD-L2-positive HSCs, and coupled with robust IFN signaling compared with control, GFP-conjugated PD-L2nb (Garcin et al., 2014). These findings support the use of nanobodies for achieving targeted IFN therapy without the harmful side effects that have previously limited IFNs clinical use.

Importantly, to fully appreciate the significance of IFN-β as part of a TNBC-targeted therapy, future studies will need to determine which TNBC-specific antigens should be targeted, and define the optimal timing of IFN-β delivery to the tumor relative to additional drug treatments. Furthermore, drug combinations capable of best accentuating the effects of IFN-β (chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or additional immunotherapies, such as anti-PD-L1, anti-PD1, or anti-CTLA4). Indeed, preclinical work is beginning to answer these important questions. For example, Brockwell et al. (2017) have shown that administration of IFN-β before surgical resection significantly improves response rates to immunotherapies such as anti-PD1/anti-PDL-1. Once treatment paradigms for using IFN-β in preclinical studies are established, we envision proceeding with clinical trials to test whether IFN-β therapy can significantly improve patient survival in TNBC.

Conclusion

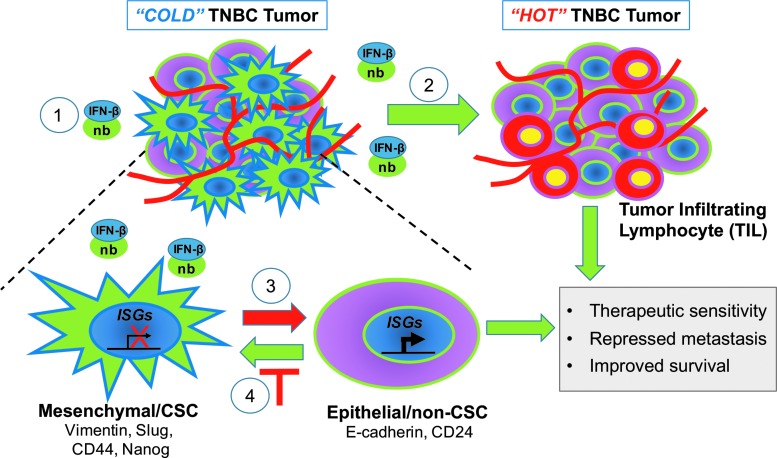

Emerging research is highlighting the positive, clinical role of IFN-β in TNBC. Since TNBC lacking both IFN/STAT signaling and TILs (“COLD” tumors) have increased CSC, we envision that restoration of IFN signaling will shift these tumors into immunologically “HOT” tumors (Fig. 1). In addition to increasing the immunologic response, our research suggests that restoring IFN signaling will effectively differentiate aggressive, therapy-resistant mesenchymal/CSC into an epithelial–non-CSC state by repressing expression of stem and EMT genes. Moreover, IFN signaling may also prevent the dedifferentiation of non-CSC by tumor microenvironment (TME) cytokines or chemotherapy, suppressing the induced emergence of drug-tolerant cells with CSC properties. Key goals are now to restore IFN signaling to achieve maximal therapeutic efficacy with minimal side effects. Taken together, our recent findings suggest that IFN-β could be utilized as a CSC-targeted therapy for the successful treatment of TNBC. We propose using nanobody technology to localize IFN-β to the breast TME of difficult-to-treat “COLD” tumors, to locally activate the immune system and induce CSC differentiation, offering hope to patients suffering from this aggressive, difficult-to-treat disease.

FIG. 1.

IFN-β as a CSC-targeted therapy for TNBC. New therapeutic strategies.  , Targeted delivery of IFN-β to the tumor microenvironment of “COLD” TNBC tumors using nanobodies conjugated to IFN-β;

, Targeted delivery of IFN-β to the tumor microenvironment of “COLD” TNBC tumors using nanobodies conjugated to IFN-β;  , IFN-β converts immune-repressed “COLD” TNBC tumors into immune-activated “HOT” TNBC tumors with TIL recruitment/activity;

, IFN-β converts immune-repressed “COLD” TNBC tumors into immune-activated “HOT” TNBC tumors with TIL recruitment/activity;  , IFN-β targets and differentiates mesenchymal/CSC to a less aggressive Epithelial/non-CSC state;

, IFN-β targets and differentiates mesenchymal/CSC to a less aggressive Epithelial/non-CSC state;  , IFN-β prevents tumor cell dedifferentiation to a mesenchymal/CSC state. CSCs, cancer stem cells; IFN, interferon; TILs, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes; TNBC, triple-negative breast cancer.

, IFN-β prevents tumor cell dedifferentiation to a mesenchymal/CSC state. CSCs, cancer stem cells; IFN, interferon; TILs, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes; TNBC, triple-negative breast cancer.

Acknowledgments

The work discussed in this review was funded by the Cancer Biology Training (Grant CBTG T32CA198808 to M.R.D.), American Cancer Society (Grant RSG-CCG-122517 to M.W.J.), and Grant NCI R21CA198808 (to M.W.J.).

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- Bidwell BN, Slaney CY, Withana NP, Forster S, Cao Y, Loi S, et al. (2012). Silencing of Irf7 pathways in breast cancer cells promotes bone metastasis through immune escape. Nat Med 18, 1224–1231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brockwell NK, Owen KL, Zanker D, Spurling A, Rautela J, Duivenvoorden HM, et al. (2017). Neoadjuvant interferons: critical for effective PD-1-based immunotherapy in TNBC. Cancer Immunol Res 5, 871–884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burstein MD, Tsimelzon A, Poage GM, Covington KR, Contreras A, Fugua SA, et al. (2015). Comprehensive genomic analysis identifies novel subtypes and targets of triple-negative breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res 21, 1688–1698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheon H, Holvey-Bates EG, Schoggins JW, Forster S, Hertzog P, Imanaka N, et al. (2013). IFNβ-dependent increases in STAT1, STAT2, and IRF9 mediate resistance to viruses and DNA damage. EMBO J 32, 2751–2763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty MR, Cheon H, Junk DJ, Vinayak S, Varadan V, Telli ML, et al. (2017). Interferon-beta represses cancer stem cell properties in triple negative breast cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114, 13792–13797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essers MA, Offner S, Blanco-Bose WE, Waibler Z, Kalinke U, Duchosal MA, et al. (2009). IFNalpha activates dormant haematopoietic stem cells in vivo. Nature 458, 904–908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcin G, Paul F, Staufenbiel M, Bordat Y, Heyden JVD, Wilmes S, et al. (2014). High efficiency cell-specific targeting of cytokine activity. Nat Commun 5, 3016.1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y, Liu C, Muyldermans S. (2017). Nanobody-based delivery systems for diagnosis and targeted tumor therapy. Front Immunol 8, 1–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling X, Marini F, Konopleva M, Schober W, Shi Y, Burks J, et al. (2010). Mesenchymal stem cells overexpressing interferon-β inhibit breast cancer growth and metastases through stat3 signaling in a syngeneic tumor model. Cancer Microenviron 3, 83–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker BS, Rautela J, Hertzog PJ. (2016). Antitumour actions of interferons: implications for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer 16, 131–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porritt RA, Hertzog PJ. (2015). Dynamic control of type I IFN signaling by an integrated network of negative regulators. Trends Immunol 36, 150–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sistigu A, Yamazaki T, Vacchelli E, Chaba K, Enot DP, Adam J, et al. (2014). Cancer cell-autonomous contribution of type I interferon signaling to the efficacy of chemotherapy. Nat Med 20, 1301–1309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slaney CY, Moller A, Hertzog PJ, Parker BS. (2013). The role of type I interferons in immunoregulation of breast cancer metastasis to the bone. Oncoimmunology 2, 1–3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steeland S, Vandenbrouke RE, Libert C. (2016). Nanobodies as therapeutics: big opportunities for small antibodies. Drug Discov Today 21, 1076–1113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weichselbaum RR, Ishwaran H, Yoon T, Nuyten DS, Baker SW, Khodarev N, et al. (2008). An interferon-related gene signature for DNA damage resistance is a predictive marker for chemotherapy and radiation for breast cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105, 18490–18495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Zhang X, Fu ML, Weichselbaum RR, Gajewski TF, Guo Y, et al. (2014). Targeting the tumor microenvironment with IFN-β bridges innate and adaptive immune responses. Cell 25, 37–48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu LY, Tang J, Zhang CM, Zeng WJ, Yan H, Li MP, et al. (2017). New immunotherapy strategies in breast cancer. Int J Environ Res Public Health 14, 1–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]