Abstract

Human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT) encodes the catalytic subunit of telomerase, which has been shown to be upregulated in many cancers. Pterostilbene is a naturally occurring stilbenoid and phytoalexin found primarily in blueberries that exhibits antioxidant activity and inhibits the growth of various cancer cell types. Therefore, the aim of this study was to determine whether treatment with pterostilbene, at physiologically achievable concentrations, can inhibit the proliferation of breast cancer cells and down-regulate the expression of hTERT. We found that pterostilbene inhibits the cellular proliferation of MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells in both a time- and dose-dependent manner, without significant toxicity to the MCF10A control cells. Pterostilbene was also shown to increase apoptosis in both breast cancer cell lines. Dose-dependent cell cycle arrest in G1 and G2/M phase was observed after treatment with pterostilbene in MCF-7 and MDA-231 cells, respectively. hTERT expression was down-regulated after treatment in both a time- and dose-dependent manner. Pterostilbene also reduced telomerase levels in both cell lines in a dose-dependent manner. Moreover, cMyc, a proposed target of the pterostilbene-mediated inhibition of hTERT, was down-regulated both transcriptionally and posttranscriptionally after treatment. Collectively, these findings highlight a promising use of pterostilbene as a natural, preventive and therapeutic agent against the development and progression of breast cancer.

Keywords: Pterostilbene, hTERT, Telomerase, cMyc, Cancer, Breast cancer, Physiological concentrations, Blueberries

Pterostilbene (trans-3,5-dimethoxy-4-hydroxystilbene) is a dimethylether analogue of resveratrol and a naturally occurring phytoalexin found primarily in blueberries but also in various other berries [1, 2]. However, studies have shown that compared to resveratrol, pterostilbene exhibits a much higher bioavailability, which is likely due to its two methoxy groups that allow for greater lipophilicity and a higher potential for cellular uptake [3, 4]. A study by Ferrer at al. [5] showed that after separately dosing mice intravenously with 20 mg/kg of pterostilbene and resveratrol and measuring the drug concentrations in plasma after 5 min, pterostilbene levels were over twice that of resveratrol. Moreover, after 480 min, approximately 1μmol/L of pterostilbene remained in the plasma, whereas roughly the same concentration of resveratrol was present in the plasma after only 60 min. Collectively, the half-life of pterostilbene and resveratrol was determined to be 77.9 and 10.2 mins, respectively, further solidifying the superior stability of pterostilbene. In a study by Kapetanovic et al. [6], oral dosing rats by gavage with pterostilbene and resveratrol for 14 consecutive days showed that pterostilbene was bioavailable in the blood plasma at roughly 80%, compared to a 20% bioavailability of resveratrol.

Pterostilbene has also been shown to exhibit antioxidative, antiproliferative and anticancerous properties [1, 7-9]. A recent study revealed that treatment of MCF-7 and Bcap-37 breast cancer cells with pterostilbene induced apoptosis, G1 cell cycle arrest, and cyto-protective autophagy [8]. However, it should be noted that the aforementioned study used abnormally high drug concentrations, which are not considered to be physiologically achievable and would likely have normal cell cytotoxic effects. An analysis by Rimando et al. [2] found that certain varieties of blueberries can contain as much as 15 μg of pterostilbene per 100 grams, which translates to consuming roughly two servings or 1 cup of berries. Pterostilbene has also been shown to be more effective at inducing apoptosis in estrogen receptor (ER)-negative breast cancer cells. It was shown that ER-α66-negative cells exhibited a higher rate of pterostilbene-induced apoptosis when compared to ER-α66- positive cells. The study found that the expression of ER-α-36, a variant of ER-α66 and widely expressed in ER-α66-negative cells, promotes pterostilbene-mediated apoptosis in breast cancer cells [10]. This novel discovery could have large implications on the treatments used in ER-negative breast cancers, which are often the most aggressive and least treatable phenotypes due to the inability to administer certain hormonal therapies. Moreover, the findings of this study suggest the potential use of pterostilbene as a form of personalized therapy to target ER-α36 in ERα66-negative breast cancer patients.

Recent studies have also suggested that pterostilbene could be used as a novel inhibitor of the telomerase enzyme. Tippani et al. [10] performed molecular docking studies to evaluate the potential interactions between pterostilbene and the active site of telomerase. The findings demonstrated that pterostilbene has a docking energy of -7.10 kcal/mol and exhibited a relatively good interaction with telomerase's active site. Furthermore, that study reported that pterostilbene significantly inhibited telomerase activity in MCF-7 breast cancer cells and NCI H-460 lung cancer cells at a concentration of 80 μM after 72 h. MCF-7 and NCI H-460 exhibited an 81.52% and 74.69% telomerase reduction, respectively, compared to the control. Although of great interest, the drug concentrations used in the Tippani et al. [10] study are considered to be quite high with respect to physiological achievability. We therefore explored not only physiologically relevant concentrations of pterostilbene but also gene regulation of hTERT, the active subunit of telomerase, as well as its effects on a number of other parameters relevant to its anticancer activity.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

All human cell lines were obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA). MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells, which are HER2-negative, as well as estrogen- and progesterone receptor-negative and MCF-7 breast cancer cells, which are estrogen and progesterone receptor-positive and HER2-negative, were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) (Mediatech Inc, Manassas, VA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Atlanta Biologicals, Lawrenceville, GA) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Mediatech). MCF10A is a human immortalized, non-tumorigenic breast epithelial cell line that is commonly used as a control (Meeran et al., 2010) and was used as such in this particular study. They were grown in DMEM/F-12 medium (Mediatech) supplemented with 5% equine serum (Atlanta Biologicals), 20 ng/mL of epidermal growth factor (Sigma), 100 ng/mL of cholera endotoxin (Sigma), 0.5 μg/mL of hydrocortisone (Sigma), 2 mM L-glutamine and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Mediatech). All cells were subcultured at 75-80% confluence and maintained in an incubator at 5% CO2, with a controlled temperature of 37°C.

Chemicals

Pterostilbene (>97% pure; HPLC) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Cat#: P1499). The bioactive compound was prepared in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) at a stock concentration of 50 mM and stored at -20°C. Cells were treated with fresh pterostilbene every 24 h after seeding for the entire treatment period. DMSO (0.2 μL/1 mL) was used as the vehicle control.

MTT analysis

The viability of the breast cancer cells was examined via the uptake of 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2, 5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT). Approximately 5000 breast cancer cells were plated in 96-well plates and allowed to adhere to the bottom of the plate overnight. Cells were then treated with increasing doses of pterostilbene (0, 5, 7.5 or 10 μM) for 3 and 6 days to determine dose- as well as time-dependency. At the conclusion of each treatment, cells were incubated with 100 μL of 1 μg/mL MTT solution for 4 h at 37°C. Afterwards, 200 μL of DMSO was added to each well to dissolve the formazan crystals. Absorbance of the dye in viable cells was measured at 595 nm using a microplate reader (iMark, BioRad). Relative cellular viability was calculated as a percentage of the DMSO vehicle control.

Cell cycle analysis

Approximately 2 × 105 cells/2 mL media were plated in 6-well plates and allowed to adhere to the bottom of the plates overnight. Cells were then treated with pterostilbene dissolved in fresh media at either 0, 5, 7.5 or 10 μM for 3 days. After treatment, cells were fixed overnight using 70% ethanol and then washed, pelleted and re-suspended in 0.04 mg/mL of propidium iodide (PI), 0.1% TritonX-100 and100 mg/mL RNA in PBS. Stained DNA contents were analyzed using flow cytometry.

Apoptosis analysis

Breast cancer cells were plated at a density of 2 × 105 cells/2 mL media in 6-well plates and allowed 24 h to adhere to the bottom of the plates. Cells were then treated with either 0, 5, 7.5 or 10 μM pterostilbene for 3 and 6 days. After treatment, cells were washed with PBS, stained with Annexin V and PI in binding buffer, and allowed to incubate for 15 min in the dark. Cells were analyzed via flow cytometry.

Clonogenic assay

Cells were plated at approximately 500 cells/well in 6-well plates in triplicate and allowed to adhere overnight. Afterwards, cell culture media was changed and cells were treated with 0, 5, 7.5 or 10 μM pterostilbene. Cells were then allowed to incubate in an incubator at 37°C for 10 days, during which time the cells were allowed to proliferate and form colonies. On day 10, the media was removed and the colonies washed with cold phosphate buffer saline, fixed with cold 70% methanol and stained with 0.5% crystal violet staining solution. After staining, pictures were taken to capture colony formation and proliferation potential after pterostilbene treatment.

Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

RT-PCR was used to examine the expression of the particular gene of interest. RNA was extracted according to the manufacture's protocol using RNeasy Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Ten μg of RNA was transcribed to cDNA using a cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), as per the manufacture's protocol.

Quantitative real-time PCR

The PCR primer sets used were as follows: forward 5′-AGG GGC AAG TCC TAC GTC CAG-3′ and reverse 5′-CAC CAA CAA GAA ATC CAC C-3′, at Tm 57°C for hTERT; forward 5′-AAT GAA AAG GCC CCC AAG GTA GTT ATC C-3′ and reverse 5′-GTC GTT TCC GCA ACA AGT CCT CTT C-3′, at Tm 60°C for cMyc; forward 5′-ACC ACA GTC CAT GCC ATC AC-3′ and reverse 5′-TCC ACC CTG TTG CTG TA-3′, at Tm 55°C for GAPDH. All reactions were performed in triplicate and SYBR green supermix (Bio-Rad) was used as the fluorescent dye in Roche Light Cycler 480. Reactions were thermally initiated at 94°C for 4 min and run for 35 cycles of 94°C for 15 s, 60°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s. GAPDH was used as an endogenous control and a vehicle control was used as a calibrator. The relative gene expression was calculated using the cycle threshold (Ct) method. The mean Ct values were calculated from triplicate measurements and the target gene expression was determined using the following formula: fold change in gene expression, 2−ΔΔCt = 2−{ΔCt (treated samples)-ΔCt(untreated control)}, where ΔCt = Ct (gene of interest)- Ct (GAPDH) and Ct represents threshold cycle number.

Western blot analysis

Protein extraction was performed using RIPA lysis buffer (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY) following the manufacturer's protocol. Protein concentration was determined with the Bradford method of protein quantification using the Bio-Rad protein assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Roughly 50 μg of nuclear protein extract were loaded onto a 4-15% Tris-HCl gel (Bio-Rad) and separated by electrophoresis at 200 V until the dye reached the end of the gel. The separated protein was then transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane using the Trans-Blot Turbo transfer system (Bio-Rad) at 25 V for 7 min. Following transfer, the membrane was blocked in 0.5% dry milk in Tris Buffered saline solution with 1% Tween (TBST) according to the protocol of the SNAP i.d. 2.0 protein detection system (EMD Millipore, Billerica, Massachusetts). Primary and secondary antibody incubation was completed according to the manufacturer's protocol. The monoclonal antibodies used in this study were: hTERT (Alpha Diagnostics, Cat#: EST21-A) cMyc (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Cat#: sc-40) and β–Actin (Cell signaling, Cat#: 13E5). Secondary antibodies used in this study include donkey against rabbit IgG (Millipore, Cat#: AP182P) and donkey against mouse (Millipore, Cat#: AP192P), conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP). Immunoreactive bands were visualized using the Bio-Rad ChemiDoc XRS+ system.β–Actin was used as the internal control to which the hTERT and cMyc bands were quantified and normalized using densitometry (ImageJ).

Telomerase PCR ELISA analysis

The TeloTAGGG Telomerase PCR ELISA kit (Roche Life Science) was used to measure the telomerase activity after drug treatment. Approximately 10 μg of protein was added to the PCR reaction mixture provided in the kit. PCR will then be run for 30 cycles (25°C for 20 min, 94°C for 5 min, 94°C for 30 s, 50°C for 30 s, 72°C for 90 s and 72°C for 10 min). Afterwards, 5 μL of the amplified PCR product was used for the ELISA assay. 20 μL of denaturing buffer was added to each sample and incubated at room temperature for 10 min. Next, 225 μL of hybridization buffer was added to the mixture and vortexed to ensure complete mixing. After, 100 μL of the hybridized mixture was added to the coated microplates provided in the kit and incubated at 37°C for 2 h at 300 rpm. The total volume allowed for each sample to be added to the microplate in duplicates. Following this incubation period, each well was washed three times with 250 μL of washing buffer for 30 s each. Next, 100 μL of substrate solution was added to the wells and incubated at room temperature for 20 min at 300 rpm, after which 100 μL of stop solution was added. The color change was then measured by spectrophotometer at 450 nm with a 690 nm reference wavelength and the data quantified.

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance between treated and control sample values was determined via one-way ANOVA using GraphPad Prism version 4.00 for Windows, GraphPad Software, San Diego, California, USA, www.graphpad.com. In each case, p<0.05 was considered statistically significant and p<0.01 highly statistically significant.

Results

Effect of Pterostilbene on the Cellular Viability of MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 Breast Cancer Cells

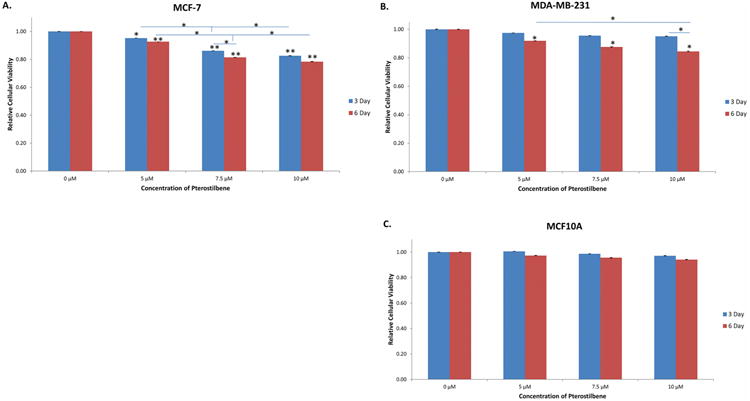

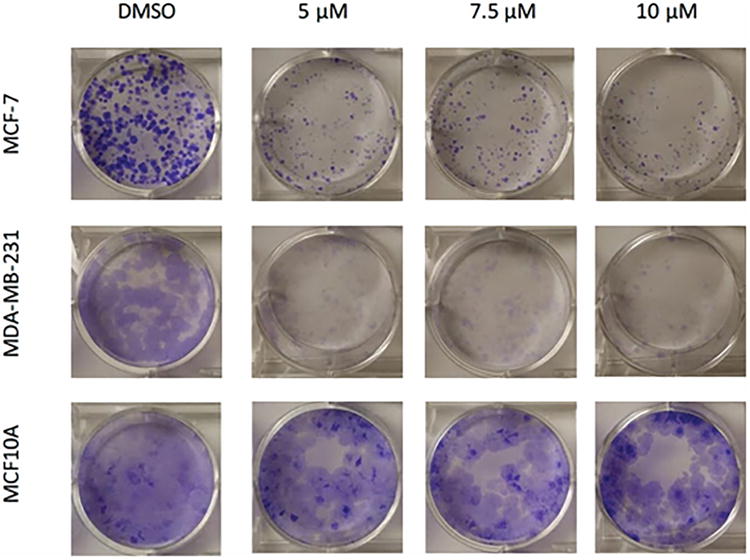

To determine dose- and time-dependent effects of pterostilbene on the viability of breast cancer cells, MTT and colony formation assays were performed. As shown in Fig. 1A-C, both MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells exhibited a dose- and time-dependent decrease in viability after treatment with pterostilbene, when compared to the DMSO control. In MCF-7 cells, there was a significant decrease in cellular viability at 5 μM after 3 days of treatment, with highly significant decreases at 7.5 and 10 μM. After 6 days of treatment, all concentrations (5, 7.5 and 10 μM) resulted in a highly significant decrease in cellular viability. In MDA-MB-231 cells, there was significant growth inhibition after 6 days of treatment at 5, 7.5 and 10 μM. None of the doses of pterostilbene had a significant effect on the viability of the MCF10A control breast cells. To investigate the long-term effects of pterostilbene treatment on the tested breast cancer cell lines, colony forming assays were performed. Pterostilbene inhibited the colony forming potential of both MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells in a dose-dependent manner, without inhibiting the growth potential of the MCF10A cells (Fig. 2).

Figure 1. Effect of pterostilbene on cellular viability. Pterostilbene inhibited the cellular viability of MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells in both a dose- and time-dependent manner.

(A) After treatment, MCF-7 cells exhibited a significant decrease in cellular viability at 5 μM after 3 days and a highly significant decrease at 7.5 and 10 μM when compared to the DMSO control. A highly significant decrease was seen at 5, 7.5 and 10 μM after 6 days of treatment. Moreover, there was a significant decrease in cellular viability between treatment concentrations after both 3 and 6 days of treatment. (B) MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells exhibited a decrease in viability after 3 days of treatment. A significant decrease was seen after 6 days at 5, 7.5 and 10 μM when compared to the control, with a significant difference in viability between 5 and 10 μM. Moreover, there was a significant difference in viability at 10 μM after 3 and 6 days of treatment. (C) There was no significant decrease in cellular viability seen in the MCF10A control cells. Values are representative of three, independent experiments and are shown as a percentage of the control ± SE; *p<0.05, **p<0.01.

Figure 2. Effect of pterostilbene on colony forming potential.

A clonogenic assay was performed to evaluate the long term effects of pterostilbene on MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells. After treatment, pterostilbene was shown to inhibit the colony forming potential of both MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells in a dose-dependent manner. No notable inhibition was seen in MCF10A control cells, when compared to the cancer lines.

Effect of Pterostilbene on Apoptosis

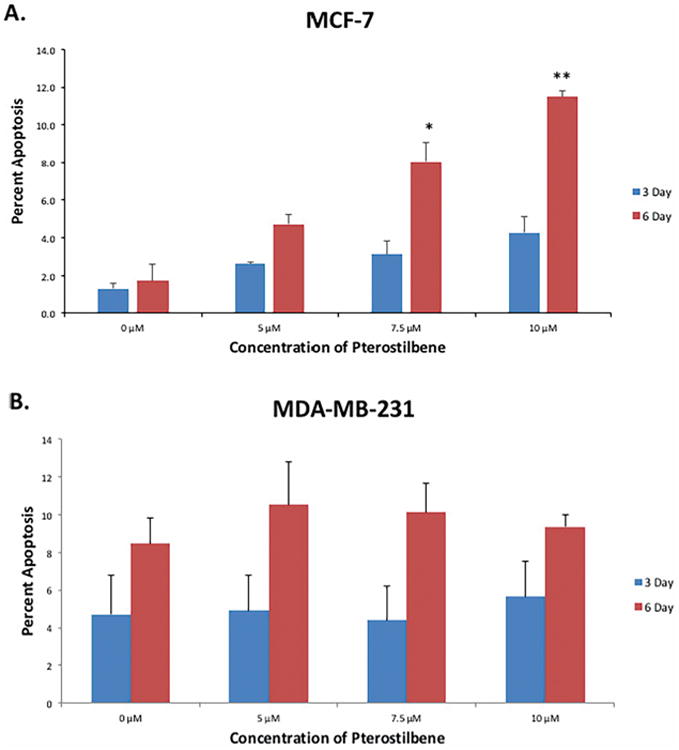

Apoptosis is a major mechanism by which many chemopreventive agents target the process of carcinogenesis [11]. Previous studies have shown that pterostilbene can induce apoptosis in various types of cancer; however, these studies often used extremely high concentrations that would likely be physiologically unachievable, as well as potentially toxic to normal cells [8, 9]. We sought to study whether pterostilbene could be effective in inducing apoptosis in two different breast cancer cells lines at physiologically achievable concentrations that would not result in normal cell toxicity. Figure 3A shows that pterostilbene can induce apoptosis in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. After 6 days of treatment, there was a dose-dependent increase in apoptosis after treatment, with significant increases at 7.5 and 10 μM when compared to the DMSO control. Figure 3B shows that pterostilbene increased the percentage of apoptosis after 6 days of treatment in MDA-MB-231 cells. Collectively, these observations suggest that pterostilbene can increase apoptosis in breast cancer cells at physiologically relevant concentrations and could potentially serve as a natural, chemopreventive agent.

Figure 3. Effect of pterostilbene on apoptosis in breast cancer cells.

(A) MCF-7 cells underwent significant apoptosis at 7.5 and 10 μM after 6 days of treatment. (B) MDA-MB-231 cells exhibited an increase in apoptosis after 6 days of treatment at 5, 7.5 and 10 μM, when compared to the DMSO control. No significant increases were observed after 3 days in either cell line. Values are representative of three, independent experiments and are shown as a percentage of the control ± SE; *p<0.05, **p<0.01.

Effect of Pterostilbene on Cell Cycle Arrest

Cell cycle analysis revealed a predominant arrest of MCF-7 cells in G1 phase, with increasing arrest in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4A). Figure 4B reveals a primary arrest of MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells in G2/M phase, also in a dose-dependent manner.

Figure 4. Effect of pterostilbene on cell cycle arrest in breast cancer cells after 72 h.

(A) Pterostilbene primarily arrested MCF-7 cells in G1 phase after treatment in a dose-dependent manner. (B) MDA-MB-231 were primarily arrested in G2/M phase after treatment with pterostilbene in a dose-dependent manner.

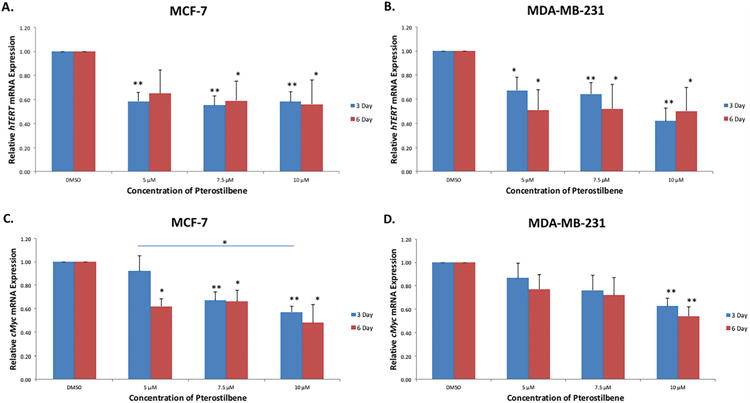

Effect of Pterostilbene on hTERT and cMyc

The expression levels of hTERT and cMyc were analyzed to explore any potential correlative or mechanistic effects that pterostilbene may have on the tested breast cancer cell lines. hTERT has been shown to be upregulated in over 90% of cancers and could serve as a potential target in chemopreventive therapies [12-15]. Fig. 5A shows that hTERT mRNA is highly significantly down-regulated after 3 days of treatment with pterostilbene. There was also a significant down-regulation of hTERT after 6 days at 7.5 and 10 μM, when compared to the DMSO control. This may suggest a threshold effect of pterostilbene on the hTERT gene in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Treatment in MDA-MB-231 cells revealed a similar trend to that of MCF-7 cells. As shown in Fig. 5B, pterostilbene significantly inhibited hTERT expression after 3 days, with a highly significant down-regulation at 7.5 and 10 μM. There was also a significant inhibition of hTERT after 6 days of treatment; however, this inhibition was less significant at 7.5 and 10 μM, when compared to 3 days, again suggesting a threshold effect.

Figure 5. Effect of pterostilbene on the expression of hTERT and cMyc.

(A) hTERT expression was highly significantly decreased in MCF-7 cells at 5, 7.5 and 10 μM after 3 days of treatment when compared to the DMSO control. However, there was no significant dose-dependency shown. After 6 days of treatment, hTERT was significantly inhibited at 7.5 and 10 μM when compared to the control. (B) Pterostilbene significantly inhibited hTERT in MDA-MB-231 cells after 3 days, with high significance shown at 7.5 and 10 μM. hTERT was also significantly inhibited at 5, 7.5 and 10 μM after 6 days. (C) cMyc expression was decreased after treatment with pterostilbene in MCF-7 cells. Inhibition was highly significant at 7.5 and 10 μM after 3 days. There was also a statistically significant difference in the level of inhibition between 5 and 10 μM after 3 days of treatment. cMyc was significantly inhibited at 5, 7.5 and 10 μM after 6 days of treatments. (D) There was both a dose- and time-dependent decrease in cMyc expression in MDA-MB-231 cells after treatment with pterostilbene. A highly significant reduction was seen at 10 μM after both 3 and 6 days when compared to the control. Values are representative of three, independent experiments and are shown as a percentage of the control ± SE; *p<0.05, **p<0.01.

cMyc is known to be a major activator of hTERT and its overexpression on many cancers is typically associated with hTERT overexpression [15, 16]. To explore the possibility that pterostilbene was down-regulating hTERT via suppressing cMyc expression, we examined cMyc mRNA levels after treatment. Fig. 5C shows that pterostilbene down-regulates cMyc in both a time- and dose-dependent manner in MCF-7 cells. This down-regulation was highly significant after 3 days of treatment at 7.5 and 10 μM. Significance was also shown after 6 days at 5, 7.5 and 10 μM. Treatment with pterostilbene also decreased cMyc expression in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells in both a dose- and time-dependent manner, with significant inhibition at 10 μM after both 3 and 6 days of treatment (Fig. 5D).

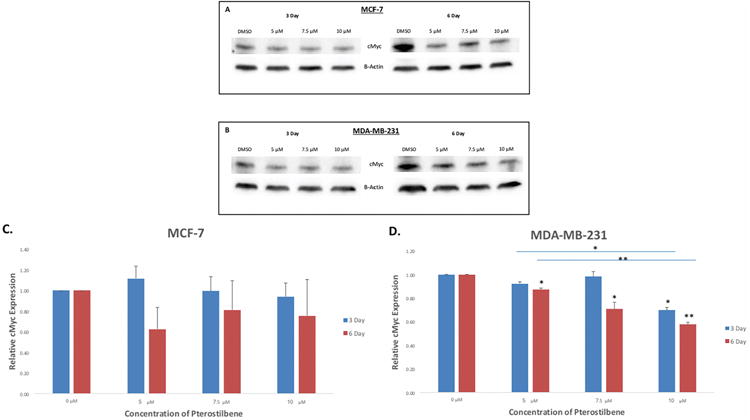

Western Blot Analysis of hTERT and cMyc

To determine whether the effects of pterostilbene treatment translates to the protein level, western blot analyses were performed on the treated cell lines. Fig. 6A shows that pterostilbene inhibits hTERT protein expression in both a dose- and time-dependent manner in MCF-7 breast cancer cells, with significant inhibition seen after 6 days at 10 μM (Fig. 6C). Pterostilbene was also shown to reduce hTERT expression in MBA-MB-231 cells in both a time- and dose-dependent manner (Fig. 6B), with significance seen at 10 μM after 3 days of treatment and high significance after 6 days at 10 μM (Fig. 6D). In MCF-7 cells, cMyc protein levels were down-regulated in both a time- and dose-dependent manner after treatment with pterostilbene, but no significance was observed (Fig. 7A, C). Pterostilbene, however, significantly decreased the expression of cMyc in both a dose- and time-dependent fashion in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells (Fig. 7B, D). These findings suggest that pterostilbene at physiological achievable concentrations can inhibit hTERT and cMyc expressions at both the gene and protein levels.

Figure 6. Western blot analysis of hTERT expression after treatment with pterostilbene.

(A) Pterostilbene inhibited the expression of hTERT in both a dose- and time-dependent manner in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. hTERT was decreased at 5, 7.5, 10 μM after 3 days when compared to the DMSO control. An even more pronounced reduction was seen after 6 days of treatment. (B) Pterostilbene inhibited the expression of hTERT in MDA-MB-231 cells in a dose- and time-dependent manner, with greater inhibition shown after 6 days versus 3 days of treatment. (C) Quantification of the western blots revealed that pterostilbene down-regulated the expression of hTERT in a time-dependent manner, with notable dose-dependency seen after 6 days of treatment in MCF-7 cells. (D) hTERT protein expression was also down-regulated in MDA-MB-231 cells in a dose- and time-dependent manner, with time-dependency plateauing at 10 μM.

Figure 7. Western blot analysis of cMyc expression after treatment with pterostilbene.

(A) Pterostilbene down-regulated the expression of cMyc in both and time- and dose-dependent manner in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. cMyc expression slightly increased at 5 μM after 3 days; however, expression was then decreased at 7.5 and 10 μM when compared to the DMSO control. After 6 days of treatment, cMyc was down-regulated at 5, 7.5 and 10 μM and was consistently lower than the expression levels after 3 days for all concentrations. (B) In MDA-MB-231 cells, cMyc levels were decreased in both a time- and dose-dependent manner. The greatest inhibition was observed after 6 days of treatment at 5, 7.5 and 10 μM, although inhibition also occurred after 3 days at 10 μM. (C) Quantification showed that pterostilbene did not significantly decrease cMyc expression in MCF-7 cells. (D) cMyc expression was significantly reduced at 10 μM after 3 days of pterostilbene treatment in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells. Significance was also observed between 5 μM and 10 μM treatments after 3 days. After 6 days, pterostilbene significantly reduced cMyc expression at 5, 7.5 and 10 μM, with highly significant reductions at 10 μM. Significance was again seen between 5 and 10 μM. Values are representative of three, independent experiments and are shown as a percentage of the control ± SE; *p<0.05, **p<0.01.

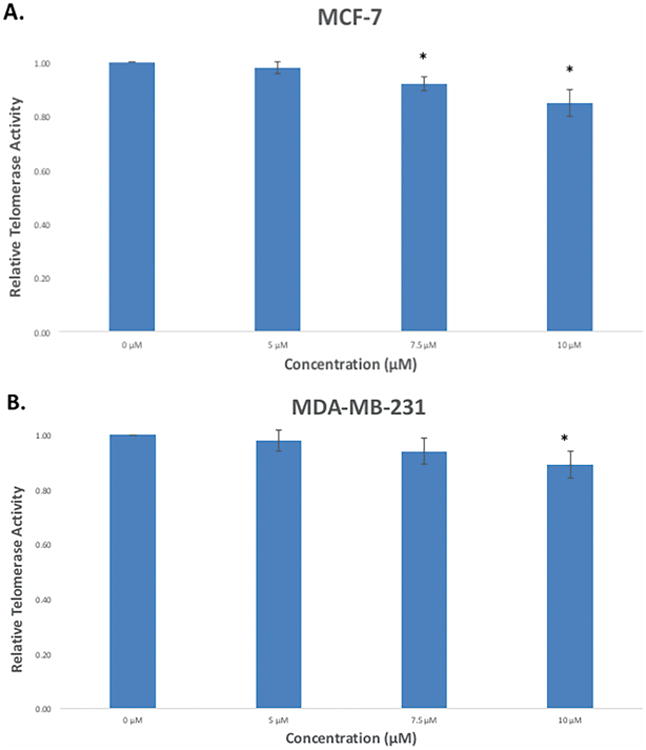

Effect of pterostilbene on telomerase expression

To fully examine the pterostilbene-mediated repression of hTERT, we measured telomerase activity after 72 h treatment in both MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells. Fig 8A shows that pterostilbene reduced the activity levels of telomerase in a dose-dependent manner, with significant reductions observed at 7.5 and 10 μM. In MDA-MB-231 cells, pterostilbene also inhibited the telomerase in a dose-dependent manner, with significance seen at 10 μM (Fig. 8B).

Figure 8. Effect of pterostilbene on telomerase activity in breast cancer cells after 72 h.

(A) Pterostilbene reduced the relative levels of telomerase in MCF-7 breast cancer cells in a dose-dependent manner after 72 h, with significant reductions observed at 7.5 and 10 μM. (B) In MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells, telomerase expression was down-regulated in a dose-dependent manner, with significance seen at 10 μM after 72 h. Values are representative of three, independent experiments and are shown as a percentage of the control ± SE; *p<0.05, **p<0.01.

Discussion

With growing interests in alternative, safer and more effective forms of cancer treatments and therapies, the use of dietary compounds is becoming a promising option in the use and development of new, less toxic and more effective chemopreventive and chemotherapeutic strategies [12]. Often, current therapies exhibit little specificity and usually result in off-target, cytotoxic effects and sometimes resistance. Dietary compounds like pterostilbene have been shown to exhibit both antiproliferative and anticarcinogenic effects in various forms of cancer and can potentially serve as effective replacement or adjuvant therapies in both cancer treatment and prevention [17-19]. Pterostilbene is a phytoalexin that is produced by certain plants in response to microbial infection, acting as the plants' own immune response [1]. Although the novelty and demonstrated effectiveness of such plant-based dietary compounds holds promise in the treatment and/or prevention of cancers, further investigations into their mechanistic components of action is needed, largely to address issues of stability and bioavailability [12, 14].

One goal of this study was to evaluate the antiproliferative effects of pterostilbene treatment on estrogen receptor (ER) alpha-positive (MCF-7) and ERα-negative (MDA-MB-231) breast cancer cells. Breast cancers are usually characterized by their expression of certain receptors. Those that are positive for ER, progesterone receptor (PR) and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) are typically associated with better prognoses due to their ability to be treated using hormonal therapies. However, breast cancers that lack these receptors are classified as triple-negative breast cancers (TNBC) and are often associated with a poorer prognosis and higher fatality, due to the ineffectiveness of current treatments including hormonal therapies [20]. This disparity between the two breast cancer phenotypes led us to use a TNBC cell line, as well as an ERα-positive cell type, to determine the effectiveness of pterostilbene among varying breast cancer cell types. We showed that pterostilbene inhibits the growth of both MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells at 5, 7.5 and 10 μM after 3 and 6 days (Fig. 2B,C); however, pterostilbene had a more significant effect on the inhibition of MCF-7 cells when compared to MDA-MB-231 cells. Notably, pterostilbene significantly reduced cellular viability at 5 μM after 3 days in MCF-7 but not MDA-MB-231 cells, though a reduction was still observed. Moreover, in MCF-7 cells, there were significant decreases in viability when comparing individual concentrations. MDA-MB-231 viability was, however, significantly decreased after 6 days at 5, 7.5 and 10μM. Correspondingly yet interestingly, we also showed that in MCF-7 cells, pterostilbene significantly increases apoptosis after 6 days of treatment at 7.5 and 10 μM. However, no significant increases in apoptosis were seen in MDA-MB-231 cells, although non-significant dose- and time-dependent increases were observed in both cell lines (Fig. 3A, B). This absence of significant increases in apoptosis in MDA-MB-231 cells after treatment with pterostilbene is mildly contradictory to previous studies that have shown that ER-α36, which is widely expressed in ER-α-66-negative cells, is associated with pterostilbene-induced apoptosis and antiproiferation [7]. However, a study by Alosi et al. [21] also showed that after treatment with 25 μM of pterostilbene, MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells exhibited 2.5- and 2.17-fold increases in apoptosis, respectively, further suggesting that pterostilbene-induced apoptosis may not be more prevalent in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells and that other mechanisms may be involved. The previous study also reported pterostilbene IC50 values of 26.42 ± 10.84 μM and 20.21 ± 2.88 μM in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells, respectively. Importantly, it should be noted that our study used much lower, physiologically and dietary achievable concentrations of pterostilbene, when compared to both the Pan [7] and Alosi [21] studies, as it has been previously reported that 1 cup or two servings of blueberries contains approximately 15 μg of pterostilbene [2]. Notwithstanding, our findings have great implications for the use of dietary compounds like pterostilbene to treat cancer phenotypes that do not respond to hormonal therapies like TNBCs or those that have developed a resistance to available treatments, as research has shown that unlike chemotherapy, continuous exposure of cancer cells to dietary bioactive agents does not illicit drug resistance [17].

Progression through the cell cycle is a carefully regulated process and a key determinant of cellular proliferation. Conversely, many cancers are characterized by unchecked cell cycles, leading to deregulated proliferation. Previous studies have shown that pterostilbene can block cell cycle progression in variety of cancers [9, 22]. In this study, we showed that pterostilbene arrested cells in G1 phase in a dose-dependent manner in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Our finding is consistent with other studies, where higher concentrations of pterostilbene were shown to arrest cells in G1 phase via the significant reduction of cyclin D1 after treatment [8]. Moreover, G1 arrest has been shown to be associated with p53 status, which is wild-type present in MCF-7 cells [11]. MDA-MB-231 cells, which are p53 mutant, were arrested in G2/M phase after treatment with pterostilbene, in a dose-dependent manner. Again, this finding parallels with previous studies that have involved cell lines with defective/mutant p53 statuses [11, 23].

The expression of hTERT is critical to the survival and progression of cancer cells, due in part to the maintenance of the telomeric ends of chromosomes after each replication, which essentially solves the end replication problem [13]. Importantly, targeting hTERT could prove to be a highly effective mechanism in chemopreventive therapies. In this study, we have shown for the first time that pterostilbene can down-regulate hTERT expression at concentrations that are physiologically achievable through dietary consumption of pterostilbene-rich foods. hTERT was significantly decreased at both the gene and protein levels in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells after treatment. At the transcriptional level, the down-regulation of hTERT was most significant after 3 days of treatment with no strong dose-or time-dependency. This suggests a threshold effect at which pterostilbene down-regulates hTERT and is suggestive of the short half-life of hTERT mRNA, which studies have shown to be ∼2 h [24]. At the protein level, down-regulation of hTERT by pterostilbene was most notable at 7.5 and 10 μMin both breast cancer cell types, with significance seen exclusively at 10 μM. Collectively, our findings show that pterostilbene is effective at down-regulating hTERT both transcriptionally and post-transcriptionally. Moreover, docking studies have shown that pterostilbene also has strong interactions with the active site of telomerase [10], suggesting that at least part of its effects may also be post-translational, which we confirmed via a telomerase activity quantification assay.

To study possible mechanisms by which pterostilbene down-regulates hTERT, we investigated its inhibitory effects on cMyc. cMyc is a proto-oncogene and activator of hTERT that is commonly overexpressed in a majority of human tumors and plays a pivotal role in both apoptosis and cell cycle progression, centrally sustaining the changes which occur during transformation. Interestingly, cMyc is dichotomous in nature due to its ability to induce apoptosis, as previously mentioned, and thus is not commonly the driving oncogene in early tumorigenesis [25, 26]. cMyc is also known to bind directly to the canonical E-boxes of the hTERT promoter [15], and several studies have even shown that the activation of hTERT by cMyc is direct in its effect, demonstrating that reductions in cMyc expression are accompanied by the down-regulation of hTERT transcription [27, 28]. Thus, due to its preferential binding and strong association with the activation of hTERT, we decided to investigate the potential effects of pterostilbene treatment on the expression of cMyc in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells. Our results revealed that pterostilbene down-regulates cMyc in a significant dose-dependent manner with slight time-dependency. cMyc was highly significantly down-regulated in MCF-7 cells at 7.5 and 10 μM after 3 days and significantly down-regulated at 5, 7.5 and 10 μM after 6 days of treatment. cMyc down-regulation was less significant in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells, with the only significance occurring at 10 μM after both 3 and 6 days. With MCF-7 cells, our findings reveal significant down-regulations of cMyc that correlated with significant down-regulations in hTERT expression. However, in MDA-MB-231 cells, although hTERT was significantly down-regulated at 5, 7.5 and 10 μM, cMyc was only significantly down-regulated at 10 μM. A study by Zhao et al. [29] showed that gambogic acid (GA), a natural compound, down-regulates hTERT transcriptional activity via the down-regulation of cMyc expression in gastric cancer cells. However, silencing of cMyc expression by cMyc-specific siRNA did not completely inhibit the transcriptional activity of hTERT, suggesting that there may be more than one mechanism by which hTERT transcription is down-regulated. These findings are consistent with our results and help support the correlative effects of the pterostilbene-mediated hTERT and cMyc down-regulation shown in our study. Interestingly, upon investigating cMyc at the protein level, our findings revealed somewhat paradoxical results. In MCF-7 cells, after treatment with pterostilbene, cMyc expression was only slightly reduced, although both time- and dose-dependence was observed. This is surprising after such significant reductions in the expression of the cMyc gene and could suggest some type negative feedback mechanism between cMyc and its pterostilbene-mediated repression in this particular cell line. However, in MDA-MB-231 cells, cMyc expression was significantly reduced in both a time- and dose-dependent manner, with high significance observed at 6 days, 10 μM. This, again, is slightly disparate from our transcriptional findings in which pterostilbene only significantly reduced cMyc expression at 10 μM but not at any of the lower concentrations. This could again suggest that pterostilbene is down-regulating cMyc largely through post-transcriptional mechanisms in MDA-MB-231 cells. Previous studies have reported that various microRNAs are involved in the post-transcriptional down-regulation of cMyc in certain cancer types [30]. Mao et al. [31] showed that cMyc is a direct target of miR-449a in prostate cancer cells and that the expression of miR-449a arrested those cells in G2/M phase by directly down-regulating cMyc. This is consistent with the G2/M phase arrest observed in our study in MDA-MB-231 cells treated with pterostilbene and could potentially provide an additional target in the pterostilbene-mediated down-regulation of cMyc in this breast cancer cell type. In whole, our findings present a potential mechanism by which pterostilbene targets cMyc, directly or indirectly, in the downstream inhibition of hTERT expression.

In conclusion, our findings demonstrate for the first time that pterostilbene can inhibit both the gene and protein expressions of hTERT in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells at physiologically relevant concentrations, further supporting the potential use of natural, bioactive compounds in cancer treatment, prevention, and control. cMyc, a proto-oncogene and activator of hTERT, which we proposed to be a target in the pterostilbene-mediated down-regulation of hTERT, was shown to be down-regulated after treatment with pterostilbene; although further studies are needed to determine an exact mechanism and whether this effect is direct or indirect. Moreover, pterostilbene at these physiological relevant concentrations significantly inhibited the viability of MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells, with no significant effects on the viability of control MCF10A breast epithelial cells, suggesting that cancer preventative therapies utilizing dietary compounds like pterostilbene would be cytotoxic to cancer but not normal cells. Overall, our results further reveal the potential preventive and therapeutic value of pterostilbene on breast cancer treatment and progression, which has significant implications over current chemopreventive therapies.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants from the NIH (R01 CA178441 and R01 CA204346) and the American Institute for Cancer Research to T.O.T., as well as a training grant, Cancer Prevention and Control Training Program (R25 CA047888) to M.D.

Grant sponsor: NIH; Grant numbers: R01 CA178441 and R01 CA204346; R25 CA047888

Footnotes

Author Contributions: M.D. conceived, designed, and performed the experiments with the guidance of T.O.T. The manuscript was drafted and edited by M.D. and T.O.T. All authors approved of the final version to be published.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.McCormack D, McFadden D. A review of pterostilbene antioxidant activity and disease modification. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2013;2013:575482. doi: 10.1155/2013/575482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rimando AM, et al. Resveratrol, pterostilbene, and piceatannol in vaccinium berries. J Agric Food Chem. 2004;52(15):4713–9. doi: 10.1021/jf040095e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Estrela JM, et al. Pterostilbene: Biomedical applications. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2013;50(3):65–78. doi: 10.3109/10408363.2013.805182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin HS, Yue BD, Ho PC. Determination of pterostilbene in rat plasma by a simple HPLC-UV method and its application in pre-clinical pharmacokinetic study. Biomed Chromatogr. 2009;23(12):1308–15. doi: 10.1002/bmc.1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferrer P, et al. Association between pterostilbene and quercetin inhibits metastatic activity of B16 melanoma. Neoplasia. 2005;7(1):37–47. doi: 10.1593/neo.04337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kapetanovic IM, et al. Pharmacokinetics, oral bioavailability, and metabolic profile of resveratrol and its dimethylether analog, pterostilbene, in rats. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2011;68(3):593–601. doi: 10.1007/s00280-010-1525-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pan C, et al. Estrogen receptor-α36 is involved in pterostilbene-induced apoptosis and anti-proliferation in in vitro and in vivo breast cancer. PLoS One. 2014;9(8):e104459. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0104459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang Y, et al. Pterostilbene simultaneously induces apoptosis, cell cycle arrest and cyto-protective autophagy in breast cancer cells. Am J Transl Res. 2012;4(1):44–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siedlecka-Kroplewska K, et al. Pterostilbene induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in MOLT4 human leukemia cells. Folia Histochem Cytobiol. 2012;50(4):574–80. doi: 10.5603/20257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tippani R, et al. Pterostilbene as a potential novel telomerase inhibitor: molecular docking studies and its in vitro evaluation. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2014;14(12):1027–35. doi: 10.2174/1389201015666140113112820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen H, et al. Epigallocatechin gallate and sulforaphane combination treatment induce apoptosis in paclitaxel-resistant ovarian cancer cells through hTERT and Bcl-2 down-regulation. Exp Cell Res. 2013;319(5):697–706. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2012.12.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meeran SM, Patel SN, Tollefsbol TO. Sulforaphane causes epigenetic repression of hTERT expression in human breast cancer cell lines. PLoS One. 2010;5(7):e11457. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daniel M, Peek GW, Tollefsbol TO. Regulation of the human catalytic subunit of telomerase (hTERT) Gene. 2012;498(2):135–46. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2012.01.095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kala R, et al. Epigenetic-based combinatorial resveratrol and pterostilbene alters DNA damage response by affecting SIRT1 and DNMT enzyme expression, including SIRT1-dependent γ-H2AX and telomerase regulation in triple-negative breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:672. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1693-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao Y, et al. Dual roles of c-Myc in the regulation of hTERT gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(16):10385–98. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Casillas MA, et al. Induction of endogenous telomerase (hTERT) by c-Myc in WI-38 fibroblasts transformed with specific genetic elements. Gene. 2003;316:57–65. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(03)00739-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fan P, et al. Continuous exposure of pancreatic cancer cells to dietary bioactive agents does not induce drug resistance unlike chemotherapy. Cell Death Dis. 2016;7(6):e2246. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2016.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moon D, et al. Pterostilbene induces mitochondrially derived apoptosis in breast cancer cells in vitro. J Surg Res. 2013;180(2):208–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2012.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sun Y, et al. Identification of pinostilbene as a major colonic metabolite of pterostilbene and its inhibitory effects on colon cancer cells. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2016 doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201500989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Foulkes WD, Smith IE, Reis-Filho JS. Triple-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(20):1938–48. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1001389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alosi JA, et al. Pterostilbene inhibits breast cancer in vitro through mitochondrial depolarization and induction of caspase-dependent apoptosis. J Surg Res. 2010;161(2):195–201. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2009.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mena S, et al. Pterostilbene-induced tumor cytotoxicity: a lysosomal membrane permeabilization-dependent mechanism. PLoS One. 2012;7(9):e44524. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saldanha SN, Kala R, Tollefsbol TO. Molecular mechanisms for inhibition of colon cancer cells by combined epigenetic-modulating epigallocatechin gallate and sodium butyrate. Exp Cell Res. 2014;324(1):40–53. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2014.01.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yi X, Shay JW, Wright WE. Quantitation of telomerase components and hTERT mRNA splicing patterns in immortal human cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29(23):4818–25. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.23.4818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoffman B, Liebermann DA. Apoptotic signaling by c-MYC. Oncogene. 2008;27(50):6462–72. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller DM, et al. c-Myc and cancer metabolism. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(20):5546–53. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-0977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yu J, et al. Repression of telomerase reverse transcriptase mRNA and hTERT promoter by gambogic acid in human gastric carcinoma cells. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2006;58(4):434–43. doi: 10.1007/s00280-005-0177-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Latil A, et al. htert expression correlates with MYC over-expression in human prostate cancer. Int J Cancer. 2000;89(2):172–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhao Q, et al. Posttranscriptional regulation of the telomerase hTERT by gambogic acid in human gastric carcinoma 823 cells. Cancer Lett. 2008;262(2):223–31. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Han H, et al. microRNA-206 impairs c-Myc-driven cancer in a synthetic lethal manner by directly inhibiting MAP3K13. Oncotarget. 2016;7(13):16409–19. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mao A, et al. MicroRNA-449a enhances radiosensitivity by downregulation of c-Myc in prostate cancer cells. Sci Rep. 2016;6:27346. doi: 10.1038/srep27346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]