Abstract

l‐Serine (l‐Ser) is a necessary precursor for the synthesis of proteins, lipids, glycine, cysteine, d‐serine, and tetrahydrofolate metabolites. Low l‐Ser availability activates stress responses and cell death; however, the underlying molecular mechanisms remain unclear. l‐Ser is synthesized de novo from 3‐phosphoglycerate with 3‐phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase (Phgdh) catalyzing the first reaction step. Here, we show that l‐Ser depletion raises intracellular H2O2 levels and enhances vulnerability to oxidative stress in Phgdh‐deficient mouse embryonic fibroblasts. These changes were associated with reduced total glutathione levels. Moreover, levels of the inflammatory markers thioredoxin‐interacting protein and prostaglandin‐endoperoxide synthase 2 were upregulated under l‐Ser‐depleted conditions; this was suppressed by the addition of N‐acetyl‐l‐cysteine. Thus, intracellular l‐Ser deficiency triggers an inflammatory response via increased oxidative stress, and de novo l‐Ser synthesis suppresses oxidative stress damage and inflammation when the external l‐Ser supply is restricted.

Keywords: l‐serine deficiency, oxidative stress, Phgdh, Ptgs2, Txnip

Abbreviations

- Atf4

activating transcription factor 4

- EMEM

Eagle's minimum essential medium

- Gapdh

glyceraldehyde‐3‐phosphate dehydrogenase

- GSH

glutathione

- ISR

integrated stress response

- MEF

mouse embryonic fibroblast

- Phgdh

3‐phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase

- Ptgs2

prostaglandin‐endoperoxide synthase 2

- qRT‐PCR

quantitative real‐time PCR

- l‐Ser

l‐serine

- Txnip

thioredoxin‐interacting protein

l‐Serine (l‐Ser) is synthesized de novo from 3‐phosphoglycerate via the phosphorylated pathway in which 3‐phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase (Phgdh) catalyzes the first step reaction. l‐Ser serves as a necessary precursor for the synthesis of proteins, sphingolipids, glycerophospholipids, folate metabolites, and amino acids such as glycine (Gly) and l‐cysteine (l‐Cys). Furthermore, the conversion of l‐Ser into Gly participates in the biosynthesis of purines and pyrimidines, by transferring a one‐carbon unit to tetrahydrofolate (THF). Our previous in vivo study demonstrated that severe l‐Ser deficiency in mice with systemic targeted disruption of Phgdh resulted in intrauterine growth retardation, multiple organ malformation, and embryonic lethality 1, 2. l‐Ser biosynthesis defects in humans resulting from Phgdh mutations were identified to be Ser synthesis disorders and Neu–Laxova syndrome, the symptoms of which are characterized by severe fetal growth retardation, microcephaly, and perinatal lethality 3, 4, 5. These findings have demonstrated that de novo l‐Ser synthesis is essential for embryonic development and survival in mice and humans.

We recently reported that reduced availability of intracellular l‐Ser promotes the biosynthesis and accumulation of 1‐deoxysphinganine (doxSA) and its metabolites 1‐deoxysphingolipids in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) lacking functional Phgdh (KO‐MEFs) 6. The condensation of palmitoyl‐CoA with l‐Ala instead of l‐Ser generated doxSA and its biosynthesis were triggered by an increasing ratio (> 3.0) of l‐Ala to l‐Ser within the cells. doxSA elicited the activation of stress‐activated protein kinase/Jun amino‐terminal kinase and p38 mitogen‐activated protein kinase, resulting in growth arrest and death in KO‐MEFs even in the presence of l‐Ser 7. Consistent with these observations, our microarray analysis of l‐Ser‐depleted KO‐MEFs revealed that the activation of a network containing the stress‐response‐activating transcription factor ATF4–ATF3–DNA damage‐inducible transcript 3 (Ddit3) axis was most prominent among the 560 upregulated genes 8, implying that l‐Ser deficiency causes metabolic stress in KO‐MEFs. However, the causal link between reduced l‐Ser availability and vulnerability to stress remains unexplored. Here, we show that l‐Ser‐depleted KO‐MEFs are vulnerable to oxidative stress, which is accompanied by increased expression of thioredoxin‐interacting protein (Txnip), a mediator of oxidative stress to inflammation, and the proinflammatory enzyme prostaglandin‐endoperoxide synthase 2 [Ptgs2; also known as cyclooxygenase (COX) 2]. These findings suggest that l‐Ser deficiency leads to an inflammatory response through diminished protection against oxidative stress.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

Frozen stocks of immortalized wild‐type (WT)‐ and Phgdh‐knockout (KO)‐MEFs were thawed and maintained in the complete medium, high‐glucose Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Osaka, Japan), containing 10% FBS (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and 10 μg·mL−1 gentamicin (Nacalai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan) in a humidified atmosphere at 37 °C with 5% CO2 2. To deprive MEFs of l‐Ser, the complete medium was replaced with Eagle's minimum essential medium (EMEM; Wako Pure Chemical Industries) supplemented with 1% FBS and 10 μg·mL−1 gentamicin, which contained all essential amino acids and l‐glutamine but did not include l‐Ala, l‐Asp, l‐Asn, l‐Cys, l‐Glu, Gly, l‐Pro, and l‐Ser. This medium is defined as the l‐Ser‐depleted condition, which contained 4 μm l‐Ser derived from FBS. The l‐Ser‐supplemented condition was established by adding l‐Ser (final 400 μm) to EMEM supplemented with 1% FBS and 10 μg·mL−1 gentamicin. In some experiments, KO‐MEF lines were retrovirally transduced with mouse Phgdh cDNA (KO‐MEF+Phgdh) or green fluorescent protein cDNA (Gfp; KO‐MEF+Gfp) 2 and with Atf4 short hairpin RNA (shAtf4) as previously described (T. Sayano, Y. Kawano, K. Takashima, W. Kusada, M. Udono, Y. Katakura, T. Ogawa, Y. Hirabayashi, S. Furuya, manuscript in preparation); total RNA was extracted after 6 h incubation for quantitative real‐time PCR (qRT‐PCR). To deprive MEFs of l‐Leu, the medium was replaced with DMEM (deficient in l‐Leu, l‐Arg, and l‐Lys, low glucose; Sigma‐Aldrich Japan; Tokyo, Japan) containing 1% FBS, gentamicin, 800 μm l‐Lys, and 400 μm l‐Arg, with or without 800 μm l‐Leu.

Total glutathione quantification

Knockout‐MEFs grown in DMEM with 10% FBS and 10 μg·mL−1 gentamicin were replated in either l‐Ser‐supplemented (at 40% cell confluence) or l‐Ser‐depleted (at 80% cell confluence) conditions for 24 h. Cells maintained under both conditions reached 80% cell confluence and were washed with Dulbecco's phosphate‐buffered saline (DPBS) followed by scraping from the dishes with DPBS. The cell suspensions were centrifuged at 1500 g, and each pellet was resuspended and lysed with 80 μL of 10 mm HCl. The lysates were alternately frozen and thawed twice, after which 20 μL of 5% (w/v) 5‐sulfosalicylic acid was added. The lysates were centrifuged at 8000 g for 10 min, and the supernatants were used for glutathione (GSH) measurement. The total GSH levels were quantified using the GSSG/GSH Quantification kit (Dojindo Laboratories, Kumamoto, Japan) according to the manufacturer's protocol, on a Multiskan™ FC microplate photometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Measurement of intracellular H2O2 generation

Knockout‐MEFs were seeded at 5 × 103–1 × 104 cells per well on Clear Fluorescence Black Plates (Greiner Bio‐One International GmbH, Frickenhausen, Germany) in 100 μL of complete medium and incubated overnight at 37 °C, after which the medium was replaced with EMEM containing 1% FBS with or without l‐Ser and incubated for 6 h. To detect endogenous H2O2 within cells, KO‐MEFs were washed with DPBS and incubated with 2 mm BES‐H2O2‐Ac, a cell‐permeable fluorescent probe for H2O2 (Wako Pure Chemical Industries) 9, and Hoechst 33342 (Dojindo Laboratories) for 20 min. Images were acquired using the In Cell Analyzer 1000 (GE Healthcare UK Ltd., Buckinghamshire, UK) using 360‐ and 492‐nm excitation filters, and 460‐ and 535‐nm emission filters, as previously described 10. The threshold of BES‐H2O2‐Ac intensity was set to the point at which approximately 75% of l‐Ser‐supplemented KO‐MEFs were negative, and cells were scored as positive or negative using spotfire decisionsite client 8.2 software (GE Healthcare Japan, Tokyo, Japan). This software was used to visualize and analyze the results 11, 12.

Cell viability assay

Wild‐type‐ and KO‐MEFs were seeded at 4 × 104–1 × 105 cells per well in 96‐well plates in 100 μL of the complete medium and incubated overnight (12–24 h) at 37 °C. The medium was changed to EMEM containing 10% FBS and H2O2 (0.01, 0.1, 1, 5, or 10 μm), and cells were incubated for 6 h. Live cells were counted using 3‐(4,5‐dimethylthiazol‐2‐yl)‐2,5‐diphenyltetrazolium bromide (Cell Counting Kit‐7; Dojindo Laboratories), which was added to each well and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. After gentle shaking, the absorbance of the culture medium was measured at 450 nm.

Isolation of total RNA and qRT‐PCR

Total RNA was extracted from MEFs using an RNA Isolation Kit (Roche Diagnostics Japan, Tokyo, Japan), and 1 μg of total RNA was used for cDNA synthesis. A High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, Life Technologies Japan Ltd.) was used as previously described 2, and qRT‐PCR was performed with an Applied Biosystems 7500 Real‐Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) using THUNDERBIRD SYBR qPCR Mix (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan). The primers used were as follows: Txnip forward, 5′‐AGCAGGACATGGAGCAAGTT‐3′, and reverse, 5′‐TTCTTTTTCCAGCGAGGAGA‐3′; Ptgs2 forward, 5′‐ ACAGACTGTGCCACATACTCAAGC‐3′, and reverse, 5′‐ GATACTGGAACTGCTGGTTGAAAAG‐3′; glyceraldehyde 3‐phosphate dehydrogenase (Gapdh) forward, 5′‐ACTCCCACTCTTCCACCTTCG‐3′, and reverse, 5′‐ATGTAGGCCATGAGGTCCACC‐3′.

Western blot analysis

Cells were lysed to extract the total protein, which was fractionated using SDS/PAGE, and transferred to poly vinylidene difluoride membranes as previously described 2. Membranes were probed with the following primary antibodies: anti‐Txnip (1 : 100 dilution, Medical & Biological Laboratories Company, Nagoya, Japan), anti‐Cox2 (1 : 500 dilution; Cell Signaling Technology Japan K.K., Tokyo, Japan), and anti‐Gapdh (1 : 100 000 dilution; EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). Bound antibodies were visualized and quantified as previously described 2.

Antioxidant treatments

Knockout‐MEFs were cultured in complete medium for 20 h, after which the culture medium was changed to EMEM containing 1% FBS in the absence of l‐Ser. N‐acetyl‐ l‐cysteine (NAC) was added to the culture medium at concentrations of 1 or 5 mm for 6 h, after which total RNA was extracted and used for qRT‐PCR as described above.

Statistical analyses

Data were evaluated using t‐tests to analyze differences between two groups. To analyze differences among more than two groups, one‐way analysis of variance followed by Dunnett's post hoc test was used. P‐values < 0.05 were considered significant. Data are expressed as the means ± standard error. All statistical analyses were performed using kaleidagraph 4.0 (Synergy Software, Reading, PA, USA).

Results

l‐Ser deficiency reduced glutathione and increased vulnerability to oxidative stress in Phgdh KO‐MEFs

We have previously reported that l‐Ser depletion reduces the intracellular levels of Gly, Cys, and l‐Ser 2. As both Gly and Cys are necessary precursors of GSH, we compared the total GSH levels in l‐Ser‐supplemented and l‐Ser‐depleted KO‐MEFs. Figure 1A shows that intracellular GSH levels were reduced significantly in KO‐MEFs under l‐Ser‐depleted conditions compared to l‐Ser‐supplemented conditions. We then sought to determine whether endogenous production of intracellular H2O2 was altered in KO‐MEFs under l‐Ser‐depleted conditions using BES‐H2O2‐Ac, a cell‐permeable fluorescent dye for H2O2 9. After 6‐h incubation, the percentage of BES‐H2O2 positive cells in l‐Ser‐depleted KO‐MEFs was significantly increased compared to the l‐Ser‐supplemented condition (Fig. 1B). Next, we examined the effect of H2O2 treatment on cell viability and observed that increasing the concentration of H2O2 reduced the viability of both types of MEFs (Fig. 1C). However, KO‐MEFs were more vulnerable to H2O2 than WT‐MEFs at lower H2O2 concentrations (0.1 and 0.01 μm). These observations indicated that the loss of de novo l‐Ser synthesis culminated in enhanced H2O2 generation and vulnerability to its oxidative stress.

Figure 1.

l‐Ser deficiency induces the reduction in the intracellular GSH level and resistance to oxidative stress in Phgdh KO‐MEFs. (A) KO‐MEFs were cultured under l‐Ser‐supplemented (+Ser) or l‐Ser‐depleted (–Ser) conditions for 24 h, and intracellular total GSH levels were measured by a GSH assay kit (n = 3; Student's t‐test, *P < 0.05). (B) KO‐MEFs and KO‐MEFs transduced with Phgdh (KO‐MEFs+Phgdh) were cultured under l‐Ser‐supplemented or l‐Ser‐depleted conditions for 6 h, and the production of intracellular H2O2 was analyzed using a fluorescent probe of H2O2 with In Cell Analyzer 1000 (n = 3; Student's t‐test, *P < 0.05). (C) WT‐MEFs and KO‐MEFs were cultured in complete DMEM for 16 h, and cells were cultured in EMEM containing 10% FBS supplemented with 0.01, 0.1, and 1 μm H2O2 for 6 h. Cell viability (WT‐MEFs: solid line with closed circles, KO‐MEFs: dotted line with open squares) was determined by counting the number of live cells using the MTT assay kit (WT‐MEFs, n = 3; KO‐MEFs, n = 3; Student's t‐test, *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.0005).

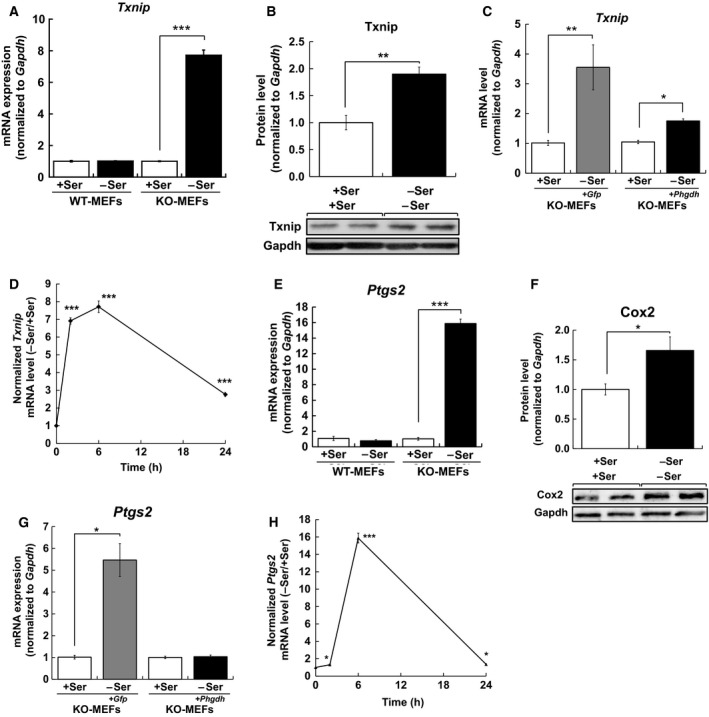

l‐Ser depletion upregulates Txnip and Ptgs2 expression in KO‐MEFs

To verify whether l‐Ser deficiency affects the oxidative stress response in KO‐MEFs, we focused on Txnip, a multifunctional protein linking oxidative stress to inflammation 12. Txnip was identified by microarray analysis as being upregulated in l‐Ser‐depleted KO‐MEFs 7, 8 and transcriptionally activated by increased H2O2 13. First, we compared Txnip mRNA levels in KO‐ and WT‐MEFs under l‐Ser‐supplemented or l‐Ser‐depleted conditions. After incubation in l‐Ser‐depleted medium for 6 h, an 8‐fold increase in Txnip mRNA was detected in KO‐MEFs but not in WT‐MEFs (Fig. 2A). Consistently, Txnip protein expression level in l‐Ser‐depleted KO‐MEFs significantly increased to 1.8‐fold higher than that in l‐Ser‐supplemented KO‐MEFs (Fig. 2B). To examine whether Txnip mRNA induction was due to Phgdh deletion, we measured the Txnip mRNA levels in KO‐MEFs+Phgdh and in KO‐MEFs+Gfp under l‐Ser‐depleted conditions. Viral transduction of Phgdh, but not Gfp, suppressed Txnip mRNA induction under l‐Ser‐depleted conditions (Fig. 2C), indicating that loss of Phgdh was primarily responsible for Txnip induction under l‐Ser‐depleted conditions. Time course analysis of Txnip mRNA expression demonstrated a sharp 7‐fold increase as early as 2 h after the exposure of l‐Ser‐depleted medium to KO‐MEFs, and a significant 3‐fold increase 24 h after exposure (Fig. 2D).

Figure 2.

Phgdh deletion induced Txnip and Ptgs2 expression caused by l‐Ser deficiency. (A,E) WT‐MEFs and KO‐MEFs were cultured under l‐Ser‐supplemented or l‐Ser‐depleted conditions for 6 h, and Txnip (A) and Ptgs2 (E) mRNA levels were measured (WT‐MEFs, n = 3; KO‐MEFs, n = 3; Student's t‐test, **P < 0.005, ***P < 0.0005). (B,F) KO‐MEFs were cultured under l‐Ser‐supplemented or l‐Ser‐depleted conditions for 6 h, and Txnip (B) and Cox2 (F) protein levels were measured by western blotting and normalized to the Gapdh protein level (KO‐MEFs, n = 3, Student's t‐test, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.005). (C,H) KO‐MEFs, KO‐MEFs transduced with Phgdh (KO‐MEFs+Phgdh), and KO‐MEFs transduced with Gfp (KO‐MEFs+Gfp) were cultured under l‐Ser‐supplemented or l‐Ser‐depleted conditions for 6 h, and Txnip (C) and Ptgs2 (H) mRNA levels were measured (KO‐MEFs, n = 3; KO‐MEFs+Phgdh, n = 3; KO‐MEFs+Gfp, n = 3; Student's t‐test, **P < 0.005, ***P < 0.0005). (D,G) KO‐MEFs were cultured under l‐Ser‐supplemented or l‐Ser‐depleted conditions for 2 h, 6 h, and 24 h, and Txnip (D) and Ptgs2 (G) mRNA levels were measured by qRT‐PCR and normalized to the Gapdh mRNA level (KO‐MEFs, n = 3, Student's t‐test, *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.0005).

Next, we tested whether the expression of Ptgs2, a proinflammatory enzyme, was also induced in l‐Ser‐depleted KO‐MEFs, because Txnip participates in the regulation of Ptgs2 expression 14, 15. We compared Ptgs2 mRNA levels in KO‐MEFs and found that after 6‐h incubation, a substantial 16‐fold increase in Ptgs2 mRNA was detected in the l‐Ser‐depleted condition compared to the l‐Ser‐supplemented condition, while WT‐MEFs did not show such an increase in l‐Ser‐depleted conditions (Fig. 2E). Accordingly, a significant increase in Ptgs2 protein was observed in l‐Ser‐depleted KO‐MEFs compared to those in l‐Ser‐supplemented conditions (Fig. 2F). As with Txnip (Fig. 2C), viral transduction of Phgdh cDNA but not Gfp suppressed Ptgs2 mRNA induction (Fig. 2G). Time course analysis of Ptgs2 mRNA expression demonstrated a subtle but significant 1.3‐fold increase after 2‐h incubation of KO‐MEFs in l‐Ser‐depleted medium, which reached a plateau after 6‐h incubation, and retained a 1.4‐fold increase even after 24 h (Fig. 2H). These observations indicated that reduced l‐Ser availability caused by Phgdh disruption results in the upregulation of both mRNA and protein levels of Txnip and Ptgs2 within 6 h.

Transcriptional activation of Txnip and Ptgs2 is independent of the integrated stress response pathway

To gain insight into the underlying molecular mechanisms by which Txnip expression was upregulated under l‐Ser‐depleted conditions, we examined whether the integrated stress response (ISR) pathway, which is activated by amino acid deficiency, regulated Txnip expression in l‐Ser‐depleted KO‐MEFs. It has been well documented that deprivation of one or more amino acids can induce the activation of the ISR pathway, which results in enhanced phosphorylation of the translation initiation factor 2α and subsequent increased expression of the transcription factor Atf4 16, 17. As a result of amino acid deprivation, Atf4 target genes are substantially induced 18. As we have demonstrated that l‐Ser depletion in KO‐MEFs causes a robust increase in Atf4 protein expression (Sayano et al., manuscript in preparation) and upregulation of several Atf4‐target genes 2, 7, we sought to determine whether Txnip and Ptgs2 induction was regulated by Atf4 via the ISR pathway. To evaluate the functional involvement of Atf4 in KO‐MEF transcription, we generated shRNA‐mediated Atf4 knockdown (KD)‐KO‐MEFs, in which Atf4 protein expression was suppressed by 0.4‐fold under l‐Ser‐depleted conditions compared to mock‐treated KO‐MEFs (Sayano et al., manuscript in preparation). As shown in Fig. 3A,B, Txnip and Ptgs2 induction in Atf4 KD‐KO‐MEFs was unchanged compared to mock KO‐MEFs under l‐Ser‐depleted conditions, suggesting that Atf4 and the ISR pathway did not play a role in Txnip and Ptgs2 induction in l‐Ser‐depleted KO‐MEFs. The ISR pathway is activated in response to the deficiency of indispensable amino acids, especially l‐Leu 16, 17, 18.

Figure 3.

Txnip and Ptgs2 induction is not associated with the ISR pathway activated by amino acid deficiency in l‐Ser‐depleted KO‐MEFs. (A,B) Mock‐ and shAtf4‐transduced KO‐MEFs were cultured under l‐Ser‐supplemented or l‐Ser‐depleted conditions for 6 h, and Txnip (A) and Ptgs2 (B) mRNA levels were measured (mock‐transduced KO‐MEFs, n = 3; shAtf4‐transduced KO‐MEFs, n = 3; Student's t‐test, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.005). (C,D) KO‐MEFs were cultured under l‐Leu‐supplemented or l‐Leu‐depleted conditions for 6 h, and Txnip (C) and Ptgs2 (D) mRNA levels were measured (KO‐MEFs, n = 3, Student's t‐test, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.005, ***P < 0.0005).

We then investigated whether the depletion of the indispensable amino acid l‐Leu could induce Txnip and Ptgs2 expression in KO‐MEFs. Figure 3C,D shows that l‐Leu depletion elicited significant increases in Txnip and Ptgs2 expression, although the magnitudes of induction were lower than those observed during l‐Ser‐depleted conditions (Fig. 3C,D). These observations suggest that l‐Ser deficiency plays a more profound role in Txnip and Ptgs2 expression than l‐Leu deficiency.

Antioxidant addition suppresses Txnip and Ptgs2 expression caused by l‐Ser depletion

To clarify the upstream mechanism underlying the upregulation of Txnip and Ptgs2 seen in l‐Ser‐deficient KO‐MEFs, we examined the effects of antioxidant treatment on mRNA expression. The addition of NAC, a GSH precursor, caused significant suppression of mRNA expression of both Txnip and Ptgs2 in KO‐MEFs under l‐Ser‐depleted conditions (Fig. 4A,B). These results suggest that increasing oxidative stress elicited by l‐Ser depletion causes the upregulation of Txnip and Ptgs2 in KO‐MEFs.

Figure 4.

Antioxidant NAC treatment suppresses Txnip and Ptgs2 induction caused by l‐Ser deficiency. (A,B) KO‐MEFs were cultured under l‐Ser‐supplemented or l‐Ser‐depleted conditions in the presence of 1 mm or 5 mm NAC for 6 h, and Txnip (A) and Ptgs2 (B) mRNA levels were measured (KO‐MEFs, n = 3; Dunnett's post hoc test, ***P < 0.0005).

Discussion

This study demonstrated that intracellular l‐Ser deficiency caused by Phgdh deletion and external l‐Ser depletion elicited increased vulnerability to oxidative stress via the reduction in GSH, which led to the induction of Txnip and Ptgs2 expression in nonmalignant MEFs. GSH is synthesized from l‐Glu, l‐Cys, and Gly and prevents damage to cellular components against oxidative stress generated by intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS). Several studies in cancer cells have reported that the intracellular levels of l‐Ser, Gly, and GSH decrease after exposure to H2O2 19, and l‐Ser and Gly depletion leads to decreased GSH levels and increased cell death in p53−/− or p21−/− HCT116 cells 20. Our observations in KO‐MEFs, indicating that the Phgdh‐dependent l‐Ser biosynthetic pathway plays a primary role for maintaining the intracellular GSH level and preventing cell death under nutritional stress conditions, are consistent with these reports 21, 22.

We demonstrated that l‐Ser depletion induced Txnip expression in KO‐MEFs. Txnip, also known as vitamin D3‐upregulated protein 1, was originally identified as a negative regulator of thioredoxin 1/2 (Trx), a key sensor of cellular redox status that regulates protection against oxidative stress. The Trx–Txnip complex is a critical regulator of intra‐ and extracellular redox signaling and ROS 23. Txnip expression is upregulated by ROS 12, 24, 25 and oxidative stress caused by ischemic–reperfusive injuries 26, 27. This study showed that Txnip expression was induced by l‐Ser depletion in KO‐MEFs, and this was inhibited by viral transduction of Phgdh cDNA (Fig. 2A–C). It is well documented that Txnip links oxidative stress to inflammation by activating NLR family pyrin domain containing 3 11, 28, 29, and participates in the upregulation of Ptgs2 expression 13, 14. The ISR pathway is an oxidative stress defense mechanism in response to essential amino acid deficiency 16. This study showed that Txnip induction caused by l‐Ser deficiency was not suppressed by Atf4 KD in l‐Ser‐depleted KO‐MEFs (Fig. 3A), indicating that Txnip induction is independent of the ISR pathway. Txnip induction by l‐Ser depletion was significantly suppressed by the addition of an antioxidant (Fig. 4A). These observations suggest that Txnip expression is increased by reduced l‐Ser availability, linking aberrant redox regulation and the induction of an inflammatory response to l‐Ser deficiency that is independent of the ISR pathway.

Txnip affects the inflammatory response and cell death signaling by regulating the cellular redox status 30, and loss of Txnip can lead to the proliferation of cancer cells 31. We previously reported that l‐Ser‐depleted KO‐MEFs exhibited cell growth arrest and increased cell death after 96‐h incubation, which was associated with diminished mRNA translation and aberrant sphingolipid metabolism 2, 6, 7. In addition to GSH, proteins, and lipids, Phgdh expression has been proved to be critical to maintain molecules important for cell proliferation, including reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate 32, purine nucleotides 33, and THF metabolites 18, 33. Taken together, the present study implies that the loss of de novo l‐Ser biosynthesis leads to cell proliferation arrest, followed by oxidative stress and inflammation, which seems to be a more severe cellular consequence compared to the loss of other nonessential amino acids but comparable to the severe phenotypes caused by the genetic deficiency of Gln 34. We demonstrated that L‐Ser deficiency promotes the biosynthesis and accumulation of doxSA, which can activate p38 MAPK in L‐Ser‐depleted KO‐MEFs 7. As Txnip expression was induced by H2O2 via p38 MAPK activation in human aortic smooth muscle cells 35, further study is needed to clarify whether p38 MAPK regulates Txnip induction in l‐Ser‐depleted KO‐MEFs. These insights might contribute to the elucidation of the pathobiology of patients with Neu–Laxova syndrome/l‐Ser deficiency disorders 3, 4, 5, 34 or diseases associated with increased Txnip expression such as diabetes and obesity 23.

Author contributions

MH and SF designed the study and wrote the manuscript. MH, YH, TS, YA, CZ, YK, and KM performed the experiments. TS, MU, and YK prepared contributed Atf4‐transduced KO‐MEFs. TO prepared contributed Phgdh‐transduced KO‐MEFs. HK supervised contributed to the analysis of microarray data.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported in part by KAKENHI Grants‐in‐Aid (No. 20248014) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

References

- 1. Yoshida K, Furuya S, Osuka S, Mitoma J, Shinoda Y, Watanabe M, Azuma N, Tanaka H, Hashikawa T, Itohara S et al (2004) Targeted disruption of the mouse 3‐phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase gene causes severe neurodevelopmental defects and results in embryonic lethality. J Biol Chem 279, 3573–3577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sayano T, Kawakami Y, Kusada W, Suzuki T, Kawano Y, Watanabe A, Takashima K, Arimoto Y, Esaki K, Wada A et al (2013) l‐Serine deficiency caused by genetic Phgdh deletion leads to robust induction of 4E‐BP1 and subsequent repression of translation initiation in the developing central nervous system. FEBS J 280, 1502–1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shaheen R, Rahbeeni Z, Alhashem A, Faqeih E, Zhao Q, Xiong Y, Almoisheer A, Al‐Qattan SM, Almadani HA, Al‐Onazi N et al (2014) Neu‐laxova syndrome, an inborn error of serine metabolism, is caused by mutations in PHGDH. Am J Hum Genet 94, 898–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Acuna‐Hidalgo R, Schanze D, Kariminejad A, Nordgren A, Kariminejad MH, Conner P, Grigelioniene G, Nilsson D, Nordenskjöld M, Wedell A et al (2014) Neu‐Laxova syndrome is a heterogeneous metabolic disorder caused by defects in enzymes of the L‐serine biosynthesis pathway. Am J Hum Genet 95, 285–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. El‐Hattab AW, Shaheen R, Hertecant J, Galadari HI, Albaqawi BS, Nabil A and Alkuraya FS (2016) On the phenotypic spectrum of serine biosynthesis defects. J Inherit Metab Dis 39, 373–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Esaki K, Sayano T, Sonoda C, Akagi T, Suzuki T, Ogawa T, Okamoto M, Yoshikawa T, Hirabayashi Y and Furuya S (2015) l‐Serine deficiency elicits intracellular accumulation of cytotoxic deoxysphingolipids and lipid body formation. J Biol Chem 290, 14595–14609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sayano T, Kawano Y, Kusada W, Arimoto Y, Esaki K, Hamano M, Udono M, Katakura Y, Ogawa T, Kato H et al (2016) Adaptive response to l‐serine deficiency is mediated by p38 MAPK activation via 1‐deoxysphinganine in normal fibroblasts. FEBS Open Bio 6, 303–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hamano M, Sayano T, Kusada W, Kato H and Furuya S (2016) Microarray data on altered transcriptional program of Phgdh‐deficient mouse embryonic fibroblasts caused by ʟ‐serine depletion. Data Brief 7, 1598–1601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Maeda H, Fukuyasu Y, Yoshida S, Fukuda M, Saeki K, Matsuno H, Yamauchi Y, Yoshida K, Hirata K and Miyamoto K (2004) Fluorescent probes for hydrogen peroxide based on a non‐oxidative mechanism. Angew Chemie Int Ed Engl 43, 2389–2391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zhao C, Sakaguchi T, Fujita K, Ito H, Nishida N, Nagatomo A, Tanaka‐Azuma Y and Katakura Y (2016) Pomegranate‐derived polyphenols reduce reactive oxygen species production via SIRT3‐mediated SOD2 activation. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2016, 2927131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Udono M, Kadooka K, Yamashita S and Katakura Y (2012) Quantitative analysis of cellular senescence phenotypes using an imaging cytometer. Methods 56, 383–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zhou R, Tardivel A, Thorens B, Choi I and Tschopp J (2010) Thioredoxin‐interacting protein links oxidative stress to inflammasome activation. Nat Immunol 11, 136–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fratelli M, Goodwin LO, Ørom UA, Lombardi S, Tonelli R, Mengozzi M and Ghezzi P (2005) Gene expression profiling reveals a signaling role of glutathione in redox regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102, 13998–14003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Perrone L, Devi TS, Hosoya KI, Terasaki T and Singh LP (2009) Thioredoxin interacting protein (TXNIP) induces inflammation through chromatin modification in retinal capillary endothelial cells under diabetic conditions. J Cell Physiol 221, 262–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Perrone L, Devi TS, Hosoya K‐I, Terasaki T and Singh LP (2010) Inhibition of TXNIP expression in vivo blocks early pathologies of diabetic retinopathy. Cell Death Dis 1, e65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kilberg MS, Pan XY, Chen H, Leung‐Pineda V and Pan Y (2005) Nutritional control of gene expression: how mammalian cells respond to amino acid limitation. Annu Rev Nutr 25, 59–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Harding HP, Zhang Y, Zeng H, Novoa I, Lu PD, Calfon M, Sadri N, Yun C, Popko B, Paules R et al (2003) An integrated stress response regulates amino acid metabolism and resistance to oxidative stress. Mol Cell 11, 619–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Deval C, Chaveroux C, Maurin A‐C, Cherasse Y, Parry L, Carraro V, Milenkovic D, Ferrara M, Bruhat A, Jousse C et al (2009) Amino acid limitation regulates the expression of genes involved in several specific biological processes through GCN2‐dependent and GCN2‐independent pathways. FEBS J 276, 707–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Panayiotidis MI, Stabler SP, Allen RH, Pappa A and White CW (2009) Oxidative stress‐induced regulation of the methionine metabolic pathway in human lung epithelial‐like (A549) cells. Mutat Res 674, 23–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Maddocks ODK, Berkers CR, Mason SM, Zheng L, Blyth K, Gottlieb E and Vousden KH (2013) Serine starvation induces stress and p53‐dependent metabolic remodelling in cancer cells. Nature 493, 542–546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sun L, Song L, Wan Q, Wu G, Li X, Wang Y, Wang J, Liu Z, Zhong X, He X et al (2015) cMyc‐mediated activation of serine biosynthesis pathway is critical for cancer progression under nutrient deprivation conditions. Cell Res 25, 429–444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Samanta D, Park Y, Andrabi SA, Shelton LM, Gilkes DM and Semenza GL (2016) PHGDH expression is required for mitochondrial redox homeostasis, breast cancer stem cell maintenance, and lung metastasis. Cancer Res 76, 4430–4442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yoshihara E, Masaki S, Matsuo Y, Chen Z, Tian H and Yodoi J (2014) Thioredoxin/Txnip: redoxisome, as a redox switch for the pathogenesis of diseases. Front Immunol 4, 514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Liu W, Gu J, Qi J, Zeng XN, Ji J, Chen ZZ and Sun XL (2015) Lentinan exerts synergistic apoptotic effects with paclitaxel in A549 cells via activating ROS‐TXNIP‐NLRP3 inflammasome. J Cell Mol Med 19, 1949–1955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zhang X, Zhang JH, Chen XY, Hu QH, Wang MX, Jin R, Zhang QY, Wang W, Wang R, Kang LL et al (2015) Reactive oxygen species‐induced TXNIP drives fructose‐mediated hepatic inflammation and lipid accumulation through NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Antioxid Redox Signal 22, 848–870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kim GS, Jung JE, Narasimhan P, Sakata H and Chan PH (2012) Induction of thioredoxin‐interacting protein is mediated by oxidative stress, calcium, and glucose after brain injury in mice. Neurobiol Dis 46, 440–449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nivet‐Antoine V, Cottart CH, Lemarechal H, Vamy M, Margaill I, Beaudeux JL, Bonnefont‐Rousselot D and Borderie D (2010) Trans‐Resveratrol downregulates Txnip overexpression occurring during liver ischemia‐reperfusion. Biochimie 92, 1766–1771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Oslowski CM, Hara T, O'Sullivan‐Murphy B, Kanekura K, Lu S, Hara M, Ishigaki S, Zhu LJ, Hayashi E, Hui ST et al (2012) Thioredoxin‐interacting protein mediates ER stress‐induced β cell death through initiation of the inflammasome. Cell Metab 16, 265–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Abderrazak A, Syrovets T, Couchie D, El K, Friguet B, Simmet T and Rouis M (2015) NLRP3 in flammasome: from a danger signal sensor to a regulatory node of oxidative stress and inflammatory diseases. Redox Biol 4, 296–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kim SY, Suh H, Chung JW, Yoon S and Choi I (2007) Diverse functions of VDUP1 in cell proliferation, differentiation, and diseases. Cell Mol Immunol 4, 345–351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zhou J and Chng WJ (2013) Roles of thioredoxin binding protein (TXNIP) in oxidative stress, apoptosis and cancer. Mitochondrion 13, 163–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ma EH, Bantug G, Griss T, Condotta S, Johnson RM, Samborska B, Mainolfi N, Suri V, Guak H, Balmer ML et al (2017) Serine is an essential metabolite for effector T cell expansion. Cell Metab 25, 345–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Labuschagne CF, van den Broek NJF, Mackay GM, Vousden KH and Maddocks ODK (2014) Serine, but not glycine, supports one‐carbon metabolism and proliferation of cancer cells. Cell Rep 7, 1248–1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. de Koning TJ (2013) Amino acid synthesis deficiencies. Handb Clin Neurol 113, 1775–1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Schulze PC, Yoshioka J, Takahashi T, He Z, King GL and Lee RT (2004) Hyperglycemia promotes oxidative stress through inhibition of thioredoxin function by thioredoxin‐interacting protein. J Biol Chem 279, 30369–30374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]