Abstract

Elevated alcohol reward value (RV) has been linked to higher levels of drinking and alcohol-related consequences, and there is evidence that specific drinking motives may mediate the relationship between demand and problematic alcohol use in college students, making these variables potentially important indicators of risk for high RV and alcohol problems. The present study evaluated these relationships in a high-risk sample of military veterans. Heavy-drinking (N = 68) veterans of Operations Enduring Freedom or Iraqi Freedom (OEF/OIF) completed the Alcohol Purchase Task (APT) measure of alcohol demand (RV), and standard assessments of alcohol consumption, alcohol-related problems, and drinking motives. RV was associated with overall alcohol consequences, interpersonal alcohol consequences, social responsibility consequences and impulse control consequences. Mediation analyses indicated significant mediation of the relationships between RV and a number of problem subscales by social motives, coping-anxiety motives, coping-depression motives and enhancement motives. This suggests that individuals who have a high valuation of alcohol may have increased motivation to drink in social, mood-enhancement, and coping situations, resulting in increased alcohol-related consequences. Demand and drinking motives should be examined as potential indicates of need for intervention services and as treatment targets in veterans.

Keywords: alcohol abuse, demand curve, motives, veterans

According to behavioral economic theory, substance abuse occurs when the reinforcing efficacy or reward value of alcohol or drugs is higher than that of alternative reinforcers, which leads to consistent patterns of preference for drug rewards (Bentzley, Jhou, & Aston-Jones, 2014; Rachlin, 1997). Reward value (RV) is defined as the relative degree of preference for a reinforcer and can be measured in the laboratory or the natural environment by determining the amount of behavior or some other resource (e.g., time, money) that an individual will allocate towards obtaining and using a substance (Bickel et al., 2014). There are several self-report methods of measuring individual differences in RV (Heinz et al., 2012; Skidmore et al., 2014), including hypothetical drug purchase tasks in which the participant specifies how much of the substance he or she would purchase and consume across a range of prices. Overall, drug demand tends to decrease in response to price increases, but there are individual differences in the extent to which this occurs; and demand curves generated from participant responses yield several indices of RV that are thought to represent how motivating or reinforcing a given drug is for that individual. These parameters show good test–retest reliability (Murphy et al., 2009) and associations with actual alcohol consumption in laboratory settings (Amlung, Acker, Stojek, Murphy & MacKillop, 2012; Amlung & MacKillop, 2015).

Research suggests that RV may be a useful indicator of substance use severity as a number of studies have linked demand curve indices of RV with drinking and related problems in college samples (Murphy & Mackillop, 2006; Smith et al., 2010). There is also preliminary evidence that elevated demand predicts poor response to brief alcohol interventions among college drinkers (Dennhardt, Yurasek, & Murphy, 2015; Mackillop & Murphy, 2007; Murphy, Dennhardt, et al., 2015), suggesting that demand may be a clinically useful indicator of risk for persistent substance use problems. Despite this evidence, there has been relatively little research on the utility of the demand curve as an index of risk in high-risk non-college samples (but see Bertholet, Murphy, Daeppen, Bmel, & Gaume, 2015; Mackillop et al, 2010). In one study of young Swiss men participating in mandatory military conscription, demand curve indices were related to alcohol use, number of alcohol use disorder criteria and alcohol-related consequences (Bertholet et al., 2015). In a US general adult sample, demand intensity was correlated with craving and was related to AUD symptoms, but not drinking quantity (MacKillop et al., 2010). Together, these results suggest that elevated alcohol RV is associated with higher levels of problematic drinking, but the factors that predict increased alcohol RV and factors that might mediate the relationship between RV and problematic outcomes need to be examined.

Drinking Motives and Alcohol RV

The motivational model of alcohol use posits that drinking motives function as a predictor of drinking based on the assumption that people drink in order to attain certain valued outcomes (Cox & Klinger, 1988). Drinking motives have been widely examined as predictors of problematic drinking and there is ample evidence to suggest that specific drinking motives are related to increased drinking and predict greater levels of alcohol-related problems above and beyond drinking levels (Carey & Correia, 1997; McDevitt-Murphy, Fields, Monahan, & Bracken, 2014). Specifically, coping motives and enhancement motives demonstrate the most robust association with alcohol-related consequences (Kassel et al., 2000; Molnar et al., 2010; Merrill, Wardell, & Read, 2014; Patrick, Lee, & Larimer, 2011). Coping motives involve drinking to alleviate negative affect and enhancement motives involve drinking to increase positive affect. Support for this model has been shown by research indicating alcohol-related problems are most likely for those who report both negative affect and coping motives (Martens et al., 2008).

There is also evidence to suggest that motives may play a role in the relationship between alcohol RV and drinking-related consequences. One study examined alcohol RV and motives following a negative affect manipulation and found that coping motives functioned as a moderator in the relationship between mood and demand, indicating that negative mood states may only increase alcohol reward value for those who tend to drink for coping purposes (Rousseau, Irons, & Correia, 2011). Another study found that enhancement and coping drinking motives mediated the relationship between demand and alcohol consumption and related problems (Yurasek et al., 2011), also suggesting a key role for motives in the relationship between alcohol reward value and alcohol outcomes. Despite the clear link between these factors, no studies to our knowledge have examined the role of alcohol RV and drinking motives in predicting drinking-related problems in high-risk adult samples such as military veterans, a population for whom there is a culture supporting excessive drinking (Institute of Medicine, 2012; Stahre, Brewer, Fonseca & Naimi, 2009).

The purpose of this study was to examine these factors that may contribute to risk for problematic drinking in a high-risk adult sample of military veterans. Specifically, we were interested in how elevated alcohol RV might be associated with drinking level and alcohol-related problems. We were also interested in the factors that may mediate the relationship between demand and alcohol-related problems. Additionally, because alcohol problems are heterogeneous (Midanik, Tam, Greenfield, & Caetano, 1996) and relatively little research has examined the specific types of alcohol problems that are a) experienced by Veterans and b) associated with elevated alcohol demand, we examined both total alcohol problems and problem subscales as our dependent variables. Specifically, we hypothesized that a) elevated alcohol RV would be associated with higher levels of drinking and alcohol-related consequences; and b) certain drinking motives (coping and enhancement) would mediate the relationship between elevated demand and higher levels of alcohol-related problems across a number of problem domains.

Method

Participants

Participants for this study were 68 OEF/OIF veterans recruited from a regional Veterans Affairs Medical Center (VAMC) who screened positive for heavy drinking. The sample was predominantly male (91.2%; n = 62), with a mean age of 32.31 years (SD = 8.84). In terms of race and ethnicity, 64.7% of participants (n = 44) identified as Caucasian, 27.9% (n = 19) identified as Black or African American, 1.5% (n = 1) identified as Asian, and 5.9% (n = 4) identified as multiethnic. The number of OEF/OIF deployments reported by these veterans ranged from one to four, with the majority of veterans reporting one (61.8%; n = 42) or two (29.4%; n = 20) deployments. Veterans reported serving an average of 14.93 months (SD = 8.57) in a combat zone.

Measures

Alcohol Reward Value (RV)

RV was assessed using the Alcohol Purchase Task (APT). The APT is a simulation measure that assesses self-reported hypothetical alcohol consumption and financial expenditure across a range of drink prices. Participants report the number of standard drinks they would consume during a specified time frame (5 hours) at 19 price increments ranging from zero (free) to $20 per drink. Demand curves are estimated by fitting each participant’s reported consumption across the range of prices to Hursh and Silberberg’s (2008) demand curve equation: log Q = 1og Q0 + k (e−αP − 1), where Q represents the quantity consumed, Q0 represents consumption at price = 0, k specifies the range of the dependent variable (alcohol consumption) in logarithmic units, P specifies price, and α specifies the rate of change in consumption with changes in price (elasticity). A k value of 4 was used and was determined by entering all data and selecting the “Shared between 0 and 10” option in GraphPad Prism. Several RV measures are generated from the demand curve, but we focused on the RV indices that have demonstrated the highest test-retest reliability (rs = 89 – .90 over two week interval, Murphy et al., 2009), intensity (maximum consumption when drinks are free) and Omax (maximum expenditure value), as well as elasticity of demand (sensitivity of alcohol consumption to increases in cost) given its theoretical importance in behavioral economics (Hursh & Silberburg, 2008). Previous research indicates that these RV indices are reliable, correlated with alcohol consumption and problems, and predictive of treatment response (Amlung & MacKillop, 2015; Murphy et al., 2009).

Alcohol Consumption

Past month alcohol consumption was assessed using the Timeline Follow Back (TLFB; Sobell, Brown, Leo, & Sobell, 1996). The TLFB is a semistructured method for assessing drinking that involves showing participants a calendar covering the last 30 days and asking them to retrospectively report on the number of standard drinks they consumed on each day. In addition, participants report on the amount of time spent drinking on each day. This information can be used to derive variables assessing both alcohol use frequency and quantity, and the TLFB has shown good psychometric properties in previous studies (e.g., Carey, Carey, Maisto, & Henson, 2004).

Drinking Consequences

Alcohol-related consequences were assessed using the Drinker Inventory of Consequences (DrInC; Tonigan & Miller, 2002). The DrInC is a 50-item self-report measure assessing the frequency of alcohol-related consequences across the respondent’s lifetime and over the last 3 months. Five domains of alcohol-related consequences are assessed on the DrInC, including Interpersonal, Physical, Social, Impulsive, and Intrapersonal consequences. In a previous study from this dataset, the DrInC demonstrated good internal consistency, Chronbach’s alpha = 0.91(McDevitt-Murphy et al., 2014).

Drinking Motives

Drinking motives were assessed using the Modified Drinking Motives Questionnaire – Revised (DMQ-R; Grant, Stewart, O’Connor, Blackwell, & Conrod, 2007). The DMQ-R is a 28-item measure that assesses five dimensions of drinking motives including social motives, drinking to cope with anxiety, drinking to cope with depression, enhancement, and conformity. Respondents indicate how often they drink for a particular motive using a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (almost always). Subscale scores are computed as the mean frequency ratings for each subscale (ranging from 4 to 9 items per subscale). The DMQ-R has demonstrated adequate internal consistency reliability in previous studies (e.g., Grant et al., 2007), and the DMQ-R was also used in a previous investigation from this dataset, where it demonstrated good internal consistency across the subscales (Cronbach’s alpha ranged from .59 to .96) (McDevitt-Murphy, Fields, Monahan, & Bracken, 2015).

Procedure

Data for this investigation were collected as part of the baseline phase of a brief alcohol intervention study (McDevitt-Murphy et al., 2014). Participants were recruited primarily through a specialty primary care clinic serving as an initial point of contact for OEF/OIF veterans upon entry into the VAMC system, and via flyers posted throughout the medical center. Those Veterans screened in person were given the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT; Babor, Higgins-Biddle, Saunders, & Monteiro, 2001) and were eligible for the study if they screened positive for heavy drinking with score of 8 or higher on the full measure. Those Veterans responding to advertisements were screened via phone with the consumption items on the AUDIT (AUDIT-C; Bush, Kivlahan, McDonell, Fihn, & Bradley, 1998) to reduce participant burden and were eligible for participation with a score of 4 or higher on this subset of items. Prior to participating in the intervention phase of the study, eligible participants were scheduled for a baseline assessment appointment with a clinical psychology doctoral student who administered a series of structured clinical interviews and self-report measures. All students were supervised by a licensed clinical psychologist. Study procedures were approved by the University of Memphis and VAMC Internal Review Boards, and written, informed consent was obtained prior to participation.

Data Analytic Plan

Outliers were corrected using the method described by Tabachnick and Fidell (2012) in which values that are greater than or equal to 3.29 standard deviations above the mean were changed to be one unit greater than the greatest non-outlier value. Variables that were skewed or kurtotic were transformed using logarithm and square root transformations depending on which provided a better correction. Intensity, social responsibility consequences, and conformity motives were log transformed. Omax, breakpoint, Pmax, physical consequences, and interpersonal consequences were square root transformed. All transformations used in final analyses resulted in normal distributions except for conformity motives which was skewed and kurtotic.

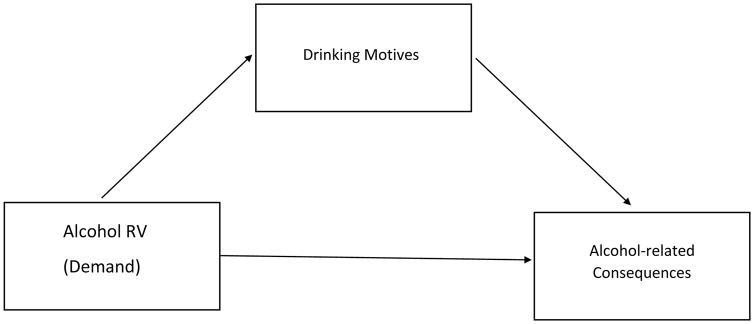

Pearson bivariate correlations were used to assess the relationship between alcohol RV, motives, alcohol use, and alcohol-related consequences. Mediation analyses were conducted to examine if alcohol use motives mediated the relationship between RV and alcohol-related problems using Preacher & Hayes’ (2008) bootstrapping methodology for indirect effects (see Figure 1 for general model). We were also able to examine the direct effects of RV on motives and problems using this model.

Figure 1.

General Mediation Model

Results

Descriptive Statistics

On average, veterans reported consuming 73.61 drinks (SD = 92.28) and 4.97 (SD = 6.87) heavy drinking episodes (>6 drinks) in the past month. They reported experiencing 9.85 (SD = 11.67) recent alcohol-related problems, which indicates a mild level of problems using norms from individuals who had met criteria for DSM-IV alcohol abuse or dependence. Veterans reported having the most problems on the physical consequences (hangovers, health problems) and impulse control (drinking and drives, being arrested) subscales. Veterans identified social motives as the most prevalent motive for drinking (M = 2.67, SD = 1.03) followed by Coping-Anxiety (M= 2.59, SD = 1.13), Enhancement (M = 2.46, SD = 1.05), Coping-Depression (M = 2.36, SD = 1.27), and Conformity (M = 1.22 SD = .50). Responses to the Alcohol Purchase Task measuring alcohol RV indicated that mean hypothetical consumption when drinks were free (intensity) was 9.85 (SD = 9.08) drinks. The mean maximum expenditure (Omax) was $21.29 (SD = 15.38), and the mean rate of consumption reduction as a function of price (elasticity) was .007 (SD = .004). The (Hursh and Silberberg, 2008) exponential demand equation provided an excellent fit (R2= .99) for the aggregated data (i.e., sample mean consumption values) and a good fit for individual participant data (mean R2 = .81). The authors used a similar criterion as Reynolds and Schiffbauer (2004) and included values for analyses only when the equation accounted for at least 30% of the variance (no participants were excluded due to this criterion).

Bivariate Associations between Alcohol Reward Value, Motives, Alcohol Use and Problems

Pearson’s r statistics were used to analyze bivariate associations between drinks per month, alcohol RV, alcohol-related problem and drinking motives (See Table 1). Demand intensity and Omax were significantly related to drinks per month and alcohol-related total consequences on the DrInC as well as several DrInC subscales (see Table 1). Intensity and Omax were most highly correlated with the interpersonal and impulse control consequences subscales, elasticity was only correlated with social responsibility consequences. Alcohol RV was also significantly associated with specific drinking motives. Specifically, high Intensity was associated with a greater degree of Social, Coping (anxiety and depression), and Enhancement motives and Omax was associated with Social and Enhancement motives. Social, Coping and Enhancement motives were also significantly related to total alcohol-related problems as well as a number of specific problem subscales, but was not significantly related to drinks consumed per month. The strongest associations were found between Social and Coping motives and interpersonal and impulse control consequences. These motives were also strongly related to social responsibility consequences.

Table 1.

Bivariate associations between alcohol demand, motives, alcohol use and problems

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Drinks Per Month | - | .483** | .448** | −.185 | .413** | .439** | .227 | .434** | .463** | .413** | .121 | −.023 | .255* | .217 | .031 |

| 2. Intensity | - | .653** | −.008 | .338** | .409* | .179 | .346** | .249 | .315* | .388** | .050 | .358** | .415** | .370** | |

| 3. Omax | - | −.339** | .305* | .395** | .234 | .365** | .398** | .328** | .350** | .109 | .149 | .112 | .248* | ||

| 4. Elasticity | - | −.064 | −.077 | −.082 | −.041 | −.150 | −.273* | −.088 | −.005 | −.004 | −.008 | −.113 | |||

| 5. Total Recent Consequences | - | .804** | .668** | .788** | .774** | .668** | .416** | .095 | .413** | .395** | .299* | ||||

| 6. Interpersonal Consequences | - | .609** | .734** | .706** | .582** | .331** | .153 | .369** | .376** | .294* | |||||

| 7. Intrapersonal Consequences | - | .499** | .627** | .470** | .077 | .032 | .160 | .186 | .078 | ||||||

| 8. Impulse control consequences | - | .646** | .573** | .425** | .181 | .402** | .424** | .337** | |||||||

| 9. Physical consequences | - | .664** | .302* | .103 | .160 | .065 | .179 | ||||||||

| 10. Social Responsibility consequences | - | .261* | .121 | .307* | .276* | .238 | |||||||||

| 11. Social Motives | - | .409** | .415** | .352** | .664* | ||||||||||

| 12. Conformity Motives | - | .403** | .393** | .366** | |||||||||||

| 13. Coping-Anxiety Motives | - | .880** | .670** | ||||||||||||

| 14. Coping- depression motives | - | .644** | |||||||||||||

| 15. Enhancement motives | - |

p ≤ 0.05;

p ≤ 0.01

Mediation Analyses

We conducted mediation analyses to examine if alcohol use motives mediated the relationship between RV and alcohol-related problems. We examined direct and indirect effects using Preacher & Hayes’ (2008) bootstrapping methodology for indirect effects based on 5000 bootstrap resamples to describe the confidence intervals of indirect effects. To limit the number of analyses, we examined mediation for models in which RV had a significant bivariate association with the motive and the motive was significantly related to the problem scale. Separate mediation analyses were run with each of the qualifying drinking motives variables as potential mediators between RV and each of the alcohol-related problem subscales. Alcohol use (drinks per month) was entered as a covariate. Bootstrap data is interpreted by determining whether zero is contained within the 95% CIs, which indicates a nonsignficant mediation effect.

Direct Effects

After controlling for drinking level, higher levels of intensity were related to endorsing more social, coping- anxiety, coping depression, and enhancement motives (see Table 2) and higher Omax was significantly associated with social and enhancement motives. After controlling for drinking level and motives, higher levels of intensity were not significantly associated with any of the alcohol-problem scales. Higher Omax was associated with more physical problems, but no other problem subscale. To explore the relation between demand and alcohol problems further, we conducted another regression that controlled for drinking level (but not motives) and found that that intensity and Omax were associated with levels of interpersonal alcohol problems.

Table 2.

Mediation of relationship between alcohol RV (Intensity) and problems by motives

| Effects (of demand) on Motives | Direct Effect | Indirect Effect | BCa* 95% CI | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| t (p) | Effect | SE | P = value | Effect | Bootstrap SE | Lower | Upper | |

| Intensity | ||||||||

| Social Motives | t = 2.85; p = .006* | |||||||

| Total Problems | 1.12 | 4.44 | .802 | 5.07* | 3.52 | .715 | 15.16 | |

| Interpersonal | .458 | .343 | .187 | .267 | .209 | −.0017 | .8104 | |

| Social Responsibility | .221 | .264 | .405 | .161 | .138 | −0.15 | .523 | |

| Impulsive | .336 | 1.04 | .747 | 1.15* | .743 | .1425 | 3.02 | |

| Coping-Anxiety | t = 2.39; p = .020* | |||||||

| Total Problems | 2.11 | 4.39 | .630 | 4.09* | 2.30 | .950 | 11.13 | |

| Interpersonal | .440 | .328 | .185 | .285* | .163 | .054 | .707 | |

| Social Responsibility | .238 | .258 | .359 | .144* | .111 | .007 | .479 | |

| Impulsive | .574 | 1.03 | .578 | .913* | .555 | .167 | 2.63 | |

| Coping-Depression | t = 3.04; p = .004* | |||||||

| Total Problems | 1.22 | 4.55 | .790 | 4.97* | 2.87 | 1.10 | 12.64 | |

| Interpersonal | .376 | .339 | .2754 | .349* | .194 | .064 | .816 | |

| Social Responsibility | .218 | .267 | .417 | .164 | .145 | −.025 | .752 | |

| Impulsive | .234 | 1.04 | .824 | 1.25* | .668 | .318 | 3.02 | |

| Enhancement | t = 3.36; p = .001* | |||||||

| Total Problems | .745 | 4.63 | .866 | 5.41* | 3.63 | .746 | 15.15 | |

| Interpersonal | .314 | .341 | .362 | .411* | .260 | .058 | 1.04 | |

| Social Responsibility | .171 | .268 | .527 | .211* | .170 | .006 | .680 | |

| Impulsive | .053 | 1.05 | .960 | 1.43* | .946 | .262 | 4.02 | |

Mediation

Results indicated a significant mediation of the relationship between intensity and total problems by social motives, coping-anxiety motives, coping-depression motives and enhancement motives (See Table 2). There were significant mediation effects between intensity and interpersonal problems by coping-anxiety motives, coping-depression motives and enhancement motives. The relationship between intensity and social responsibility problems was mediated by coping-anxiety motives and enhancement motives and the relationship between intensity and impulsive problems was mediated by social motives, coping-anxiety motives, coping-depression motives and enhancement motives.

Social motives mediated the relationship between Omax and total consequences and impulsive consequences and enhancement motives mediated the relationship between Omax and total consequences. No other models with Omax were significant. Only the results with Intensity are presented in the table for clarity.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine factors that contribute to risk for problematic drinking in military veterans. In this sample of heavy drinking veterans, alcohol demand was relatively high (e.g., reported consumption at price = 0 was almost 10 drinks), drinking was most related to social and coping motives, and veterans reported high overall levels of alcohol problems, and in particular problems related to physical consequences and impulse control. Drinking motives, particularly coping and enhancement motives have also been linked to worse drinking outcomes and studies suggest they may be important in explaining the relationship between RV and drinking problems (Rousseau et al., 2011; Yurasek et al., 2011). These prior findings led us to hypothesize that elevated alcohol RV would be associated with higher levels of drinking and alcohol-related consequences, and that certain drinking motives (coping and enhancement) would mediate the relationship between elevated RV and higher levels of alcohol-related problems.

Overall higher alcohol RV was associated with greater levels of total alcohol problems, but this relationship was not significant in models that controlled for drinking level and motives. However, Omax was significantly associated with impulse control problems in the mediation model tests of direct effects indicating that individuals with higher alcohol RV are more at risk for impulse control problems related to their drinking. This is consistent with previous research findings that elevated demand is linked to a higher likelihood of impulsive behaviors such as drinking and driving (Teeters & Murphy, 2015; Teeters, Pickover, Dennhardt, Martens, & Murphy, 2014). Intensity and Omax were also associated with more interpersonal problems, suggesting that elevated demand may predict social/relational problems even after accounting for differences in drinking level. Consistent with our hypothesis, RV was associated with endorsement of drinking motives, specifically social, coping, and enhancement motives. Bivariate associations indicated that overall endorsing these motives was associated with increased level of alcohol-related problems, but not a higher quantity of drinking, suggesting that drinking for these social, coping and enhancement reasons conveys risk above and beyond that produced by high consumption. The association between coping and enhancement motives and alcohol-related problems is consistent with previous research with other populations (Merrill et al., 2014; Patrick et al., 2011) and suggests a similar association in military veterans. Also consistent with previous research (Yurasek et al., 2011) and with our hypothesis, motives mediated the relationship between RV and alcohol-related problems. This suggests that individuals who have a high valuation of alcohol may have increased motivation to drink in mood-enhancement and coping situations, resulting in increased alcohol-related consequences. In this study, we found mediation for motives between alcohol RV and interpersonal, social responsibility and impulse control problems specifically. Other researchers have suggested that the link between motives and problems may be due to a different style of drinking (e.g., drinking at a faster pace, which would raise BAC) in the case of enhancement motives (Goodwin, 1995; Perry et al., 2006). In the case of social motives, individuals may engage in drinking behaviors to facilitate friendships, which may lead to them trying to match the drinking pace of friends or to make decisions based on what they think others may like (Gntra, Brown, & Moreno, 2013). In the case of coping motives, researchers have suggested that a lack of other effective coping methods, and lower control in decision-making while drinking (Cooper et al., 1995) may play a role. These factors could foreseeably be related to issues with personal and job-related responsibility and relationships, particularly with close friends and family, which reflect a number of the items on this subscale. This may be a particularly problematic phenomenon for military veterans given the high rate of adjustment issues including social relationships, reentry into society, and finding employment (Allen, Rhoades, Stanley, & Markman, 2010; Meis, Erbes, Polusny, & Compoton, 2011).

Limitation and Future Directions

This study had several limitations. The data were cross-sectional, and therefore it was not possible to test directionality in the relationship between alcohol RV, motives, alcohol consumption and problems. The relatively small, homogenous sample (mostly male, heavy drinkers) may have made it difficult to detect effects and may partly explain why we did not find direct effects between alcohol RV and alcohol-related problems in the mediation model. Additionally, all measures in this study were self-report. Although research suggests that hypothetical purchase tasks such as the APT are reliable and valid (Amlung et al., 2012; Amlung & MacKillop, 2015) and self-report measures of substance use are generally accurate (Hagman, Clifford, Noel, Davis, & Cramond, 2007), a biological or real-time measure of alcohol use and purchases may have been helpful as to confirm these results.

Despite these limitations, these results extend the literature by suggesting that elevated alcohol demand is linked to drinking problems in military veterans and enhancement and coping drinking motives mediate this relationship. Given these findings and that high RV has been associated with poor intervention outcomes in other populations (Dennhardt et al., 2015; Mackillop & Murphy, 2007), RV and drinking motives should be examined as a) indicators of risk and need for alcohol intervention, and b) potential targets to inform prevention and intervention efforts in veterans. Consistent with previous research (Dennhardt, Yurasek, & Murphy, 2015; Mackillop & Murphy, 2007; Murphy, Dennhardt, et al., 2015), the current results provide particular support for the clinical utility of the demand intensity (maximum consumption) and Omax (maximum expenditure) indices given their consistent pattern of association with drinking motives and problems in this sample of heavy drinking Veterans. In terms of intervention, both standard brief alcohol interventions, which frame decisions about drinking into aggregate patterns associated with risk and social/health costs, and behavioral economic approaches that aim to frame decisions about drinking and drug use in the context of overall resource (time/money) allocation (Murphy et al., 2015; Dennhardt, Yurasek & Murphy, 2015) have been shown to reduce RV and deserve more research with this population. Some brief motivational interventions have addressed motives as part of the personalized feedback (Lee et al., 2010) and motive-tailored interventions have also shown some promise (Studer et al., 2014; Wurdak, Wolstein, & Kuntsche, 2016). Research on interventions that target these risk factors warrant more research.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from NIAAA (K23 AA016120; MMM) and preparation of this manuscript was supported in part by an NIAAA R01 (R01AA020829; JGM).

We would like to acknowledge the support of the Memphis Veterans’ Affairs Medical Center office of Research and Development in completing this research.

References

- Allen ES, Rhoades GK, Stanley SM, Markman HJ. Hitting home: Relationships between recent deployment, posttraumatic stress symptoms, and marital functioning for Army couples. Journal of Family Psychology. 2010;24(3):280–288. doi: 10.1037/a0019405. doi:0.1037/a0019405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC: Author; 2000. text rev. [Google Scholar]

- Amlung M, MacKillop J. Understanding the effects of stress and alcohol cues on motivation for alcohol via behavioral economics. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2014;38(6):1780–1789. doi: 10.1111/acer.12423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amlung M, MacKillop J. Further evidence of close correspondence for alcohol demand decision making for hypothetical and incentivized rewards. Behavioural processes. 2015;113:187–191. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2015.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amlung M, Acker J, Stojek M, Murphy JG, MacKillop J. Is Talk “Cheap”? An Initial Investigation of the Equivalence of Alcohol Purchase Task Performance for Hypothetical and Actual Rewards. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research. 2012;36(4):716–724. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01656.x. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01656.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, Monteiro MG. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): Guidelines for use in primary care. World Health Organization; 2001. Audit. WHO/MNH/DAT 89.4. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Beck depression inventory-II. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1996. p. b9. [Google Scholar]

- Bentzley BS, Jhou TC, Aston-Jones G. Economic demand predicts addiction-like behavior and therapeutic efficacy of oxytocin in the rat. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2014;111(32):11822–11827. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1406324111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertholet N, Murphy JG, Daeppen JB, Gmel G, Gaume J. The alcohol purchase task in young men from the general population. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2015;146:39–44. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertholet N, Murphy JG, Daeppen JB, Gmel G, Gaume J. The alcohol purchase task in young men from the general population. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2015;146:39–44. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Koffarnus MN, Moody L, Wilson AG. The Behavioral- and Neuro-Economic Process of Temporal Discounting: A Candidate Behavioral Marker of Addiction. Neuropharmacology. 2014;76 doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.06.013. (0 0) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake DD, Weathers FW, Nagy LM, Kaloupek DG, Charney DS, Keane TM. Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-IV (CAPS-DX) National Center for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, Behavioral Science Division, Boston VA Medical Center; Boston, MA: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Bujarski S, Ray LA. Subjective response to alcohol and associated craving in heavy drinkers vs. alcohol dependents: An examination of Koob’s allostatic model in humans. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2014;140:161–167. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB, Fihn SD, Bradley KA. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Archives of internal medicine. 1998;158(16):1789–1795. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.16.1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Carey MP, Maisto SA, Henson JM. Temporal stability of the timeline followback interview for alcohol and drug use with psychiatric outpatients. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2004;65(6):774. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Correia CJ. Drinking motives predict alcohol-related problems in college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1997;58(1):100–105. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Frone MR, Russell M, Mudar P. Drinking to regulate positive and negative emotions: a motivational model of alcohol use. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69(5):990. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.5.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox WM, Klinger E. A motivational model of alcohol use. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1988;97(2):168. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.97.2.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennhardt AA, Murphy JG. Associations between depression, distress tolerance, delay discounting, and alcohol-related problems in European American and African American college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2011;25(4):595. doi: 10.1037/a0025807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennhardt AA, Yurasek AM, Murphy JG. Change in delay discounting and substance reward value following a brief alcohol and drug use intervention. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2015;103(1):125–140. doi: 10.1002/jeab.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erbes CR, Meis LA, Polusny MA, Compton JS. Couple adjustment and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in National Guard veterans of the Iraq war. Journal of Family Psychology. 2011;25(4):479. doi: 10.1037/a0024007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez VM, Reynolds B, Skewes MC. Role of impulsivity in the relationship between depression and alcohol problems among emerging adult college drinkers. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2011;19(4):303. doi: 10.1037/a0022720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin DW. Alcohol amnesia. Addiction. 1995;90(3):315–317. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1995.tb03779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant VV, Stewart SH, O’Connor RM, Blackwell E, Conrod PJ. Psychometric evaluation of the five-factor Modified Drinking Motives Questionnaire Revised in undergraduates. Addictive behaviors. 2007;32(11):2611–2632. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagman BT, Clifford PR, Noel NE, Davis CM, Cramond AJ. The utility of collateral informants in substance use research involving college students. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32(10):2317–2323. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinz AJ, Lilje TC, Kassel JD, de Wit H. Quantifying Reinforcement Value and Demand for Psychoactive Substances in Humans. Current Drug Abuse Reviews. 2012;5(4):257–272. doi: 10.2174/1874473711205040002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hursh SR, Silberberg A. Economic demand and essential value. Psychological Review. 2008;115(1):186. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.115.1.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen LK, Southwick SM, Kosten TR. Substance use disorders in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder: a review of the literature. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001 doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.8.1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakupcak M, Tull MT, McDermott MJ, Kaysen D, Hunt S, Simpson T. PTSD symptom clusters in relationship to alcohol misuse among Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans seeking post-deployment VA health care. Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35(9):840–843. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassel JD, Jackson SI, Unrod M. Generalized expectancies for negative mood regulation and problem drinking among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2000;61(2):332–340. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laibson D. A cue-theory of consumption. Quarterly Journal of Economics. 2001:81–119. [Google Scholar]

- Loewenstein G. Affect regulation and affective forecasting. Handbook of Emotion Regulation. 2007:180–203. [Google Scholar]

- MacKillop J, Murphy JG. A behavioral economic measure of demand for alcohol predicts brief intervention outcomes. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;89(2):227–233. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKillop J, Miranda R, Monti PM, Ray LA, Murphy JG, Rohsenow DJ, McGeary JE, Swift RM, Tidey JW, Gwaltney CJ. Alcohol Demand, Delayed Reward Discounting, and Craving in relation to Drinking and Alcohol Use Disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2010;119(1):106–114. doi: 10.1037/a0017513. http://doi.org/10.1037/a0017513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens MP, Neighbors C, Lewis MA, Lee CM, Oster-Aaland L, Larimer ME. The roles of negative affect and coping motives in the relationship between alcohol use and alcohol-related problems among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2008;69(3):412–419. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDevitt-Murphy ME, Fields JA, Monahan CJ, Bracken KL. Drinking motives among heavy-drinking veterans with and without posttraumatic stress disorder. Addiction Research & Theory. 2015;23(2):148–155. doi: 10.3109/16066359.2014.949696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDevitt-Murphy ME, Murphy JG, Williams JL, Monahan CJ, Bracken-Minor KL, Fields JA. Randomized controlled trial of two brief alcohol interventions for OEF/OIF veterans. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2014;82(4):562. doi: 10.1037/a0036714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDevitt-Murphy ME, Williams JL, Bracken KL, Fields JA, Monahan CJ, Murphy JG. PTSD symptoms, hazardous drinking, and health functioning among US OEF and OIF veterans presenting to primary care. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2010;23(1):108–111. doi: 10.1002/jts.20482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill JE, Wardell JD, Read JP. Drinking motives in the prospective prediction of unique alcohol-related consequences in college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2014;75(1):93–102. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Midanik LT, Tam TW, Greenfield TK, Caetano R. Risk functions for alcohol-related problems in a 1988 US national sample. Addiction. 1996;91(10):1427–1437. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1996.911014273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Tonigan JS, Longabaugh R. The Drinker Inventory of Consequences (DrInC): An instrument for assessing adverse consequences of alcohol abuse: Test manual. 95. US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Molnar A, Melnyk CW, Bassett A, Hardcastle TJ, Dunn R, Baulcombe DC. Small silencing RNAs in plants are mobile and direct epigenetic modification in recipient cells. Science. 2010;328(5980):872–875. doi: 10.1126/science.1187959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morissette SB, Woodward M, Kimbrel NA, Meyer EC, Kruse MI, Dolan S, Gulliver SB. Deployment-related TBI, persistent postconcussive symptoms, PTSD, and depression in OEF/OIF veterans. Rehabilitation Psychology. 2011;56(4):340. doi: 10.1037/a0025462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, Dennhardt AA, Yurasek AM, Skidmore JR, Martens MP, MacKillop J, McDevitt-Murphy ME. Behavioral economic predictors of brief alcohol intervention outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2015;83(6):1033–1043. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, MacKillop J. Relative reinforcing efficacy of alcohol among college student drinkers. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2006;14(2):219. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.14.2.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, MacKillop J, Skidmore JR, Pederson AA. Reliability and validity of a demand curve measure of alcohol reinforcement. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2009;17(6):396. doi: 10.1037/a0017684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, Yurasek AM, Dennhardt AA, Skidmore JR, McDevitt-Murphy ME, MacKillop J, Martens MP. Symptoms of depression and PTSD are associated with elevated alcohol demand. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2013;127(1):129–136. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens MM, Ray LA, MacKillop J. Behavioral economic analysis of stress effects on acute motivation for alcohol. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2015;103(1):77–86. doi: 10.1002/jeab.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick ME, Lee CM, Larimer ME. Drinking motives, protective behavioral strategies, and experienced consequences: Identifying students at risk. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36(3):270–273. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry PJ, Argo TR, Barnett MJ, Liesveld JL, Liskow B, Hernan JM, … Brabson MA. The Association of Alcohol-Induced Blackouts and Grayouts to Blood Alcohol Concentrations. Journal of Forensic Sciences. 2006;51(4):896–899. doi: 10.1111/j.1556-4029.2006.00161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior research methods. 2008;40(3):879–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rachlin H. Four teleological theories of addiction. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 1997;4(4):462–473. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds B, Schiffbauer R. Measuring state changes in human delay discounting: an experiential discounting task. Behavioural Processes. 2004;67(3):343–356. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau GS, Irons JG, Correia CJ. The reinforcing value of alcohol in a drinking to cope paradigm. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2011;118(1):1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneiderman AI, Braver ER, Kang HK. Understanding sequelae of injury mechanisms and mild traumatic brain injury incurred during the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan: persistent postconcussive symptoms and posttraumatic stress disorder. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2008;167(12):1446–1452. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skidmore JR, Murphy JG, Martens MP. Behavioral Economic Measures of Alcohol Reward Value as Problem Severity Indicators in College Students. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2014;22(3):198–210. doi: 10.1037/a0036490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DV, Hayden BY, Truong TK, Song AW, Platt ML, Huettel SA. Distinct value signals in anterior and posterior ventromedial prefrontal cortex. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2010;30(7):2490–2495. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3319-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Brown J, Leo GI, Sobell MB. The reliability of the Alcohol Timeline Followback when administered by telephone and by computer. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1996;42(1):49–54. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(96)01263-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahre MA, Brewer RD, Fonseca VP, Naimi TS. Binge drinking among US active-duty military personnel. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2009;36(3):208–217. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Studer J, Baggio S, Mohler-Kuo M, Dermota P, Daeppen JB, Gmel G. Differential association of drinking motives with alcohol use on weekdays and weekends. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2014;28(3):651. doi: 10.1037/a0035668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using Multivariate Statistics. Boston: Pearson Education; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Teeters JB, Murphy JG. The behavioral economics of driving after drinking among college drinkers. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2015;39(5):896–904. doi: 10.1111/acer.12695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teeters JB, Pickover AM, Dennhardt AA, Martens MP, Murphy JG. Elevated alcohol demand is associated with driving after drinking among college student binge drinkers. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2014;38(7):2066–2072. doi: 10.1111/acer.12448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers FW, Ruscio AM, Keane TM. Psychometric properties of nine scoring rules for the Clinician-Administered Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Scale. Psychological Assessment. 1999;11(2):124. [Google Scholar]

- Wurdak M, Wolstein J, Kuntsche E. Effectiveness of a drinking-motive-tailored emergency-room intervention among adolescents admitted to hospital due to acute alcohol intoxication—A randomized controlled trial. Preventive Medicine Reports. 2016;3:83–89. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2015.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yurasek AM, Murphy JG, Dennhardt AA, Skidmore JR, Buscemi J, McCausland C, Martens MP. Drinking motives mediate the relationship between reinforcing efficacy and alcohol consumption and problems. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2011;72(6):991–999. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]