Abstract

Inherited and autoimmune blistering diseases are rare, chronic, and often severe disorders that have the potential to significantly affect patients’ quality of life. The effective management of these conditions requires consideration of the physical, emotional, and social aspects of the disease. Self-esteem is integral to patients’ ability to cope with their illness, participate in treatment, and function in society. This article discusses quality-of-life studies of patients with blistering diseases with a particular focus on self-esteem issues that patients may face.

Keywords: Epidermolysis bullosa, autoimmune blistering disease, quality of life, self-esteem

Introduction

Blistering diseases encompass a heterogeneous group of congenital and acquired skin diseases of variable severity, and symptoms range from mild to life threatening. Many blistering diseases are chronic and burdensome afflictions with the capacity to considerably impinge on patients’ quality of life (QoL). Physical symptoms including pain and itch, disfigurement due to blistering and scarring, reduced functional capacity that is imposed by disability, and the economic burden and side effects that are associated with treatment all contribute to the burden of these diseases (Sebaratnam et al., 2012).

Given the pervasive impact of blistering diseases on patients’ lives, the emotional impact that is associated with these diseases is also significant. Patients’ emotional health is particularly important to consider when evaluating individual disease burden because it is often independent of clinical severity and thus may be invisible to clinicians unless specifically sought out. Similar to other dermatological diseases, patients with blistering diseases can experience shame, poor self-image, and low self-esteem (Jafferany, 2007).

Self-esteem refers to an individual’s sense of worth and is intrinsically tied to concepts such as self-confidence and body image (Mazzotti et al., 2011). Poor self-esteem can affect how patients cope with their disease, their outlook, adherence to treatment, and social functioning. Additional challenges that are faced by patients with blistering diseases include the rarity of these diseases, which results in poor awareness of the disease among the wider population, as well as the lifelong nature of blistering diseases with only variable treatment efficacy and limited supportive resources available.

During the past decade, there has been increasing interest in measuring the burden of blistering diseases in an effort to understand patients’ experiences living with the disease and the subjective and objective effects of therapeutic interventions (Dures et al., 2011, Tabolli et al., 2009). A variety of generic and disease-specific QoL tools have been used to quantify disease severity and impact. These include generic measures such as the Medical Outcome Study 36-item Short-form Survey (SF-36), dermatology-specific measures such as the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), and disease-specific instruments and qualitative studies (Sebaratnam et al., 2012).

These tools have facilitated awareness and understanding of patients’ perceptions of their disease and the impact of the disease on their wellbeing. Patients and clinicians often have different perceptions of QoL, and regular consideration of the physical, emotional, and social impact of the disease is vital to ensure the provision of holistic care. This article discusses QoL in patients with congenital and acquired (autoimmune) blistering diseases with a particular focus on the impact that living with these conditions has on patients’ self-esteem as well as implications for future practice.

Inherited blistering diseases

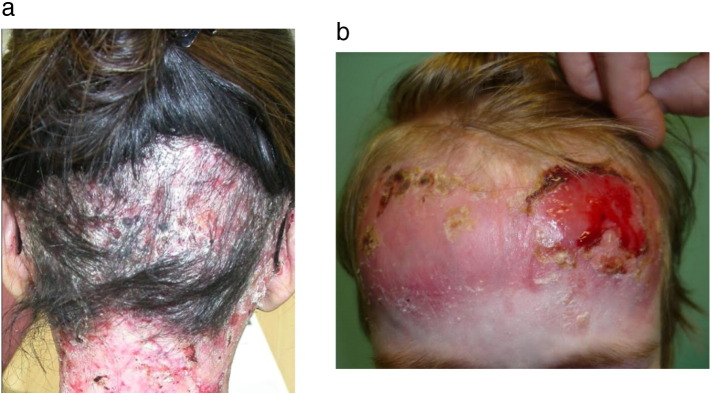

Epidermolysis bullosa (EB) encompasses a group of inherited blistering diseases that are characterized by the blistering of the skin and mucous membranes after mild mechanical trauma. The main subtypes of EB are delineated on the basis of genetic and ultrastructural characteristics of disease and include EB simplex, junctional EB, and dystrophic EB. Recessive dystrophic EB (RDEB) is the most severe form of the disease with the greatest potential for internal organ damage, significant disability, and early death (Figs. 1a and b). Unfortunately, EB is a noncurable disease and the mainstay of current management is supportive treatment in the form of painful and time-consuming dressing changes. However, a number of new clinical trials and biological therapies offer hope, at last, of a treatment that could control EB.

Fig. 1.

(a) and (b). Recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa with visible erosions and scarring alopecia that causes embarrassment and pain

Living with EB can exert a detrimental impact on the physical, emotional, and social health of afflicted patients with the burden of disease varying between the subtypes. A Scottish study of 116 patients with EB found that according to the DLQI, a validated dermatology-specific QoL tool, the impairment in QoL of patients with RDEB was greater than that of patients with any other skin disease previously assessed (Horn and Tidman, 2002). Children experienced a greater impact on their QoL compared with adults with higher average DLQI scores for both severe (22 of 30 in children; 18 of 30 in adults) and nonsevere (15 of 30 in children; 10.7 of 30 in adults) subtypes of EB. One contributor to this difference was the inability of children to participate in everyday activities due to the disease symptoms. This resulted in psychological and social sequelae and children reported feelings of isolation due to difficulties in engaging with peers.

A qualitative study that used semistructured interviews in 11 children with EB further demonstrated the frustration that children felt with the limitations that were imposed by EB. The inability to participate in common childhood activities such as sports was the third most prevalent concern after pain and itchy skin and contributed to affected children feeling different from their peers (van Scheppingen et al., 2008). This sense of being difference was exacerbated by the visibility of EB, and some children reported an awareness of a difference only after negative reactions or comments by others.

The highly visible nature of EB both in terms of blisters and dressing for treatment is particularly challenging for children at a time when concepts of self and body image emerge. Children are at a particular risk of internalizing negative reactions and therefore also at risk to develop body image-related distress and subsequent self-esteem issues (Jafferany, 2007). Indeed, one study suggested that restricted social interaction and increased psychological morbidity in patients with EB may cause adolescents in particular to be shy and introverted (Frew and Murrell, 2010).

In addition to social isolation, self-esteem may also be affected by the loss of autonomy that EB patients experience, particularly those patients with severe subtypes of the disease. A study of 425 patients with EB found that 73% of patients with severe forms such as junctional EB and recessive dystrophic EB required full assistance with activities of daily living (particularly walking and personal hygiene). In contrast, more than 90% of patients with less severe forms of EB such as EB simplex were fully independent (Fine et al., 2004).

However, clinical severity is often not associated with the severity of psychological symptoms in patients with EB, which is a phenomenon that is well-reported in other dermatological diseases. One study found that although 80% of patients with EB had subthreshold psychiatric symptoms such as anxiety and depression, symptoms were not correlated with disease severity (Margari et al., 2010) and family support and a multidisciplinary EB team along with patient advocacy groups such as the Dystrophic Epidermolysis Bullosa Research Association of America were important to help patients cope. Indeed, another study of a patient population with EB in Italy demonstrated that EB had the greatest impact on QoL in patients with higher perceived severity rather than clinical disease severity, with other contributors including higher psychological distress as measured by the General Health Questionnaire-12 in female and pediatric patients (Tabolli et al., 2009). These results mirror those from patients with significant burns, among whom self-esteem was found to be more affected by age and sex than by the size of the burns or the part of body that was burned (Bowden et al., 1980).

Interestingly, another study that developed an internationally validated, disease-specific, QoL tool for EB called the Quality of Life in EB questionnaire (QoLEB) demonstrated that patients with RDEB had better scores on the emotions subscale (measurement of patient-reported frustration, embarrassment, depression, and anxiety) compared with patients with less severe junctional EB (Cestari et al., 2016, Frew et al., 2009, Frew et al., 2013, Yuen et al., 2014). The authors postulated that this difference could be because patients with severe disease have well-developed coping mechanisms to adjust to their illness, with family and caregiver support and an individual positive outlook as key factors to develop emotional resilience (Dures et al., 2011, Frew et al., 2009).

Supporting patients by providing them with opportunities to participate in social and recreational activities can empower these patients to live a satisfying and productive life, which in turn can enhance self-esteem and wellbeing (Plante et al., 2001). Patient advocacy groups such as the Dystrophic Epidermolysis Bullosa Research Association of America have been very successful in allowing patients with EB to develop peer-support networks and participate in innovative ventures such as EB ski camps that aim to enhance patients’ overall QoL (Hwang et al., 2012, Nading et al., 2009).

Autoimmune blistering diseases

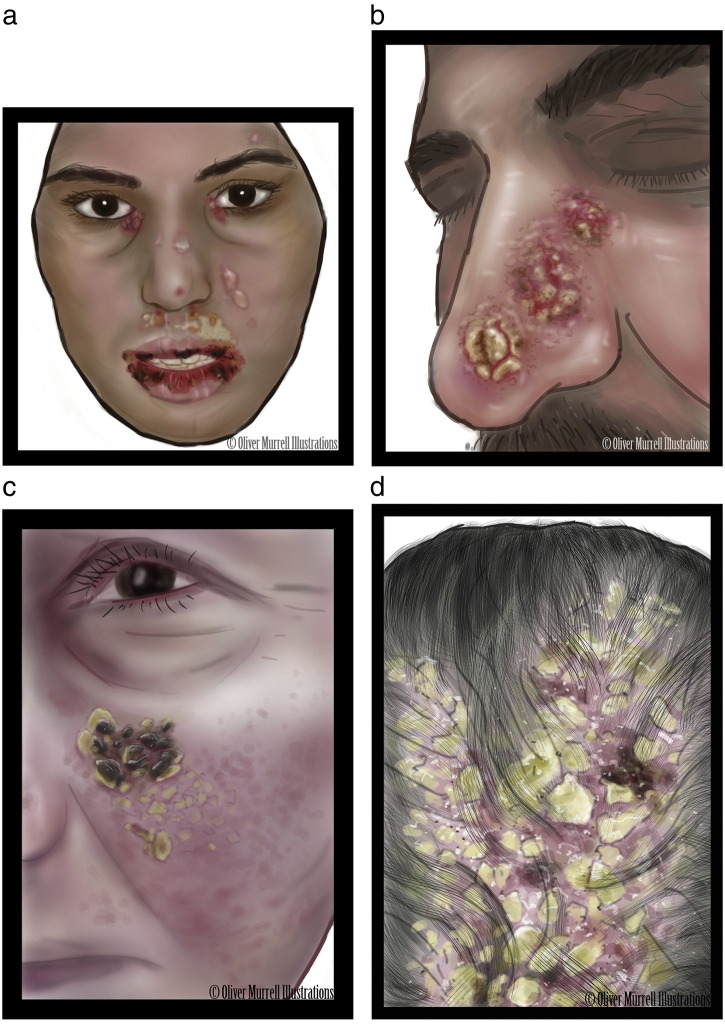

Autoimmune blistering diseases (AIBDs) refer to a group of disorders in which autoantibodies are formed against structural proteins in desmosomes or hemidesmosomes in the skin and mucous membranes, resulting in blistering and scarring. The majority of AIBDs are chronic diseases that can cause significant physical and emotional distress (Figs. 2a-d), which is exacerbated by the need to often have lifelong treatment with immunosuppressive therapies that have potentially severe adverse effects. Most QoL studies of patients with AIBD have focused on pemphigus and bullous pemphigoid, but significantly less is known about rarer AIBDs such as EB acquisita, linear immunoglobulin A bullous dermatosis, dermatitis herpetiformis, mucous membrane pemphigoid, and pemphigoid gestationis (Sebaratnam et al., 2012).

Fig. 2.

Spectrum of severity of autoimmune blistering diseases. (a) Pemphigus vulgaris that affects the face of a 14-year-old girl (b) Nasal crusted erosions in pemphigus vegetans (c) Facial lesions in a female patient with pemphigus foliaceous (d) Scalp alopecia in a female patient with pemphigus foliaceous

A study in Morocco found that the QoL was impaired in patients with pemphigus compared with those in the wider population (Terrab et al., 2005). The SF-36 scores of 30 patients with pemphigus who presented to a hospital were compared with those of 60 patients who presented to dermatology clinics with nonsevere diseases such as verrucous warts. Within the pemphigus group, 70% reported enormous shame about their appearance, 60% were anxious about negative reactions from others, and 63% had a significant loss in confidence, including concerns about the impact of the disease on sexual function (Terrab et al., 2005). Intimacy and sexual relations are often greatly affected by blistering diseases and can cause significant distress in those who are affected.

These results are similar to those from another study that found that embarrassment related to disease was of significant concern to patients, after clothing changes and itching (Tjokrowidjaja et al., 2013). QoL scores in the Moroccan study were affected most by facial involvement from pemphigus and the extent of lesions. The emotional impact of facial dermatoses can be considerable as patients experience shame and embarrassment due to the visibility of lesions, which can potentially result in exclusion, discrimination, and social rejection (Orion and Wolf, 2014). Sociocultural factors also play a role in the determination of the impact of a disease on patients’ QoL. Poor knowledge of pemphigus in Morocco resulted in misconceptions that lesions were related to poor hygiene or unconventional sexual practices and limited marriage prospects for young women (Terrab et al., 2005).

Social misconceptions may also contribute to the higher psychological morbidity that is observed in female patients. A study of 139 patients with pemphigus found that QoL was significantly worse in women who reported significantly worse physical and mental component scores in the SF-36s compared with men. Women also reported a higher prevalence of anxiety and depression (42.9% in women compared with 34.7% in men) regardless of the disease severity, which may be due to a poorer self-image in view of the social pressures on women to look after their appearance (Paradisi et al., 2009, Zhao and Murrell, 2015).

One study of 74 patients with pemphigus examined the effect of body image on psychological distress. The study researchers devised a 14-item questionnaire that examined in three parts whether patients found their body image to be defective and socially unacceptable, the impact of body image on self-esteem, and perceptions of physical attractiveness and compared these scores with patient-reported anxiety and depression levels (Mazzotti et al., 2011). Higher psychological distress was observed in patients who reported a dysfunctional investment in their appearance (odds ratio [OR]: 7.36) and in patients who had a higher perceived disease severity (OR: 6.03). Therefore, the authors suggested that cognitive aspects of disease were more important than objective measures such as lesion extent in the determination of the impact on patients’ QoL. Patients who appeared to use appearance as an index of self-worth tended to have psychological distress when comparing what their body image should be according to society standards and what it actually is, which could potentially result in a lower self-esteem.

Patients’ subjective perceptions of disease can affect patient-reported QoL even when the disease activity is minimal. One study of 203 patients with pemphigus, including 47 patients with quiescent disease, found that in the quiescent disease group, more than 20% of patients reported that they believed they often/always suffered from pemphigus (Tabolli et al., 2014). One contributor to this effect could be the ongoing burden of treatment as patients experience side effects from treatment including steroidal and immunosuppressive drugs. A recent study of 66 patients with AIBDs in Poland (mostly in partial and complete remission with therapy) also found that approximately 80% of the cohort perceived themselves to have feelings of depression, 70% reported anxiety, and 60% feelings of embarrassment (Kalinska-Bienias et al., 2017).

A recently validated 17-item questionnaire named the TABQoL may be useful to examine the impact on QoL in patients with AIBD who undergo treatment (Tjokrowidjaja et al., 2013). The TABQoL may be used in combination with the ABQoL, another disease-specific QoL tool that was proposed by the same group, which has been validated in multiple international cohorts (Kalinska-Bienias et al., 2017, Sebaratnam et al., 2013, Sebaratnam et al., 2015, Yang et al., 2017) and will provide hopefully more information on the impact on QoL in patients with a variety of AIBDs in the future.

Conclusions

Both inherited and acquired blistering diseases have the potential to significantly affect patients’ self-esteem due to the burden of painful symptoms, adverse effects of treatment, and social isolation that is related to the visibility of lesions. Therefore, a consideration of the psychological factors that are associated with the disease is an important part of management in these patients, particularly given the intractable nature of these conditions. Qualitative and quantitative QoL tools are helpful to evaluate patients’ self-reported disease impact on their wellbeing. Such tools have multiple advantages including validating patients’ concerns as clinically relevant, increasing physician understanding of the subjective severity of the disease, and establishing a more empathetic therapeutic relationship.

Beyond the medical setting, patient support and advocacy groups are pivotal in helping patients cope with their illness and raising public awareness of these rare conditions. Effective strategies need to be implemented to ensure that patients’ physical and biopsychosocial symptoms, including self-esteem, are managed with equal rigor. Future studies should examine how to implement these strategies and evaluate their efficacy on patients’ overall wellbeing.

Footnotes

Sources of support: This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Bowden M.L., Feller I., Tholen D., Davidson T.N., James M.H. Self-esteem of severely burned patients. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1980;61(10):449–452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cestari T., Prati C., Menegon D.B., Prado Oliveira Z.N., Machado M.C., Dumet J. Translation, cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the Quality of Life Evaluation in Epidermolysis Bullosa instrument in Brazilian Portuguese. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55(2):e94–9. doi: 10.1111/ijd.12819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dures E., Morris M., Gleeson K., Rumsey N. The psychosocial impact of epidermolysis bullosa. Qual Health Res. 2011;21(6):771–782. doi: 10.1177/1049732311400431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine J.D., Johnson L.B., Weiner M., Suchindran C. Assessment of mobility, activities and pain in different subtypes of epidermolysis bullosa. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2004;29(2):122–127. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2004.01428.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frew J.W., Cepeda Valdes R., Fortuna G., Murrell D.F., Salas Alanis J. Measuring quality of life in epidermolysis bullosa in Mexico: cross-cultural validation of the Hispanic version of the Quality of Life in Epidermolysis Bullosa questionnaire. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69(4):652–653. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.04.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frew J.W., Martin L.K., Nijsten T., Murrell D.F. Quality of life evaluation in epidermolysis bullosa (EB) through the development of the QOLEB questionnaire: an EB-specific quality of life instrument. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161(6):1323–1330. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frew J.W., Murrell D.F. Quality of life measurements in epidermolysis bullosa: tools for clinical research and patient care. Dermatol Clin. 2010;28(1):185–190. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2009.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn H.M., Tidman M.J. Quality of life in epidermolysis bullosa. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2002;27(8):707–710. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2230.2002.01121.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang S.J., Kim M., Kemble-Welch A., Hanely M.C., Murrell D.F. Volunteering at an adventure camp for epidermolysis bullosa. Med J Aust. 2012;197(1):54. doi: 10.5694/mja11.11549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jafferany M. Psychodermatology: a guide to understanding common psychocutaneous disorders. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;9(3):203–213. doi: 10.4088/pcc.v09n0306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalinska-Bienias A., Jakubowska B., Kowalewski C., Murrell D.F., Wozniak K. Measuring of quality of life in autoimmune blistering disorders in Poland. Validation of disease-specific Autoimmune Bullous Disease Quality of Life (ABQoL) and the Treatment Autoimmune Bullous Disease Quality of Life (TABQoL) questionnaires. Adv Med Sci. 2017;62(1):92–96. doi: 10.1016/j.advms.2016.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margari F., Lecce P.A., Santamato W., Ventura P., Sportelli N., Annicchiarico G. Psychiatric symptoms and quality of life in patients affected by epidermolysis bullosa. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2010;17(4):333–339. doi: 10.1007/s10880-010-9205-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzotti E., Mozzetta A., Antinone V., Alfani S., Cianchini G., Abeni D. Psychological distress and investment in one's appearance in patients with pemphigus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25(3):285–289. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03780.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nading M.A., Lahmar J.J., Frew J.W., Ghionis N., Hanley M., Welch A.K. A ski and adventure camp for young patients with severe forms of epidermolysis bullosa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61(3):508–511. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orion E., Wolf R. Psychologic factors in the development of facial dermatoses. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32(6):763–766. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2014.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paradisi A., Sampogna F., Di Pietro C., Cianchini G., Didona B., Ferri R. Quality-of-life assessment in patients with pemphigus using a minimum set of evaluation tools. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60(2):261–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plante W.A., Lobato D., Engel R. Review of group interventions for pediatric chronic conditions. J Pediatr Psychol. 2001;26(7):435–453. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/26.7.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Scheppingen C., Lettinga A.T., Duipmans J.C., Maathuis C.G., Jonkman M.F. Main problems experienced by children with epidermolysis bullosa: a qualitative study with semi-structured interviews. Acta Derm Venereol. 2008;88(2):143–150. doi: 10.2340/00015555-0376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebaratnam D.F., Frew J.W., Davatchi F., Murrell D.F. Quality-of-life measurement in blistering diseases. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30(2):301–307. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2011.11.008. ix. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebaratnam D.F., Hanna A.M., Chee S.N., Frew J.W., Venugopal S.S., Daniel B.S. Development of a quality-of-life instrument for autoimmune bullous disease: the Autoimmune Bullous Disease Quality of Life questionnaire. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149(10):1186–1191. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.4972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebaratnam D.F., Okawa J., Payne A., Murrell D.F., Werth V.P. Reliability of the autoimmune bullous disease quality of life (ABQoL) questionnaire in the USA. Qual Life Res. 2015;24(9):2257–2260. doi: 10.1007/s11136-015-0965-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabolli S., Pagliarello C., Paradisi A., Cianchini G., Giannantoni P., Abeni D. Burden of disease during quiescent periods in patients with pemphigus. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170(5):1087–1091. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabolli S., Sampogna F., Di Pietro C., Paradisi A., Uras C., Zotti P. Quality of life in patients with epidermolysis bullosa. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161(4):869–877. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terrab Z., Benchikhi H., Maaroufi A., Hassoune S., Amine M., Lakhdar H. Quality of life and pemphigus. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2005;132(4):321–328. doi: 10.1016/s0151-9638(05)79276-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tjokrowidjaja A., Daniel B.S., Frew J.W., Sebaratnam D.F., Hanna A.M., Chee S. The development and validation of the treatment of autoimmune bullous disease quality of life questionnaire, a tool to measure the quality of life impacts of treatments used in patients with autoimmune blistering disease. Br J Dermatol. 2013;69(5):1000–1006. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang B., Chen G., Yang Q., Yan X., Zhang Z., Murrell D.F. Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the autoimmune bullous disease quality of life (ABQoL) questionnaire. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2017;15:31. doi: 10.1186/s12955-017-0594-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuen W.Y., Frew J.W., Veerman K., van den Heuvel E.R., Murrell D.F., Jonkman M.F. Health-related quality of life in epidermolysis bullosa: validation of the Dutch QOLEB questionnaire and assessment in the Dutch population. Acta Derm Venereol. 2014;94(4):442–447. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao C.Y., Murrell D.F. Autoimmune blistering diseases in females: a review. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2015;1(1):4–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ijwd.2015.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]