Abstract

Background

The CHAARTED and STAMPEDE trials showed that the addition of docetaxel (D) to androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) prolonged longevity of men with metastatic hormone sensitive prostate cancer (mHSPC). However, the impact of upfront D on subsequent therapies is still unexplored. As abiraterone acetate (AA) and enzalutamide (E) are the most commonly used first-line treatment for metastatic CRPC (mCRPC), we aimed to assess whether they maintained their efficacy after ADT+D versus ADT alone.

Patients and Methods

A cohort of mCRPC patients treated between 2014 and 2017 with first-line AA or E for mCRPC was identified from three hospitals’ IRB approved databases. Patients were classified by use of D for mHSPC. This time frame was chosen as ADT+D became a valid therapeutic option for mHSPC in 2014 and it inherently entailed a short follow-up time on AA/E. The endpoints included overall survival (OS) from ADT start, OS from AA/E start, and time to AA/E start from ADT start. Differences between groups were assessed using the log-rank test.

Results

Of the 102 mCRPC patients identified, 50 (49%) had previously received ADT alone, while 52 (51%) had ADT+D. No statistically significant difference in any of the evaluated outcomes was observed between the 2 cohorts. Yet, deaths in the ADT+D group were 12 versus 21 in the ADT alone, after a median follow-up of 24.4 and 29.8 months, respectively.

Conclusion

In a cohort of ADT/ADT+D treated mCRPC patients with short times to first-line AA/E and follow-up, the efficacy of AA/E is similar regardless of previous use of D.

Keywords: ADT+docetaxel, CHAARTED, mCRPC, Abiraterone acetate, Enzalutamide

INTRODUCTION

Until recently, ADT by surgical or medical castration has been the standard-of-care for mHSPC [1]. Upon progression, prostate cancer is termed castration resistant and chemotherapy and second-generation androgen receptor (AR) targeting agents, such as AA and E, proven in clinical trials to increase longevity of men with mCRPC, are used in patients deemed fit [2-4]. In this regard, a recent analysis of United States (US) prescriptions reported that AA and E are the preferred (76%) first-line therapy for men with mCRPC [5].

Recently, two new regimens combining ADT with D and AA, respectively, have shown a survival advantage compared to ADT alone and became new valid therapeutic options for the patient with mHSPC [6-9]. Particularly, the chemohormonal combination showed a clear benefit for mHSPC men with high volume disease compared to ADT alone and has been introduced in the treatment paradigm of mHSPC in 2014. However, to date, there is no report in the literature evaluating the impact of early D on subsequent first-line AA or E for mCRPC and an optimal sequence of drugs after progression on ADT+D does not exist. The E3805 CHAARTED investigators demonstrated that the addition of D to ADT versus (vs.) ADT alone prolonged time to CRPC, 19.4 vs. 11.7 months with a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.61 [95% confidence interval (CI), 0.52–0.73; P<0.0001), and time to clinical progression, 33.0 vs. 19.8 months with a HR of 0.62 (95% CI, 0.51–0.75; P<0.0001), respectively [6]. Based on the similar HR data, we postulated that first-line AA or E for mCRPC at least maintained efficacy after ADT+D vs. ADT alone. The biological rationale for this hypothesis is that early D debulks AR-independent tumor cells which would otherwise thrive under the positive selective pressure exerted by ADT alone and thus enhances the efficacy of AR-targeting AA or E as first-line treatment for mCRPC [6,10]. Determining the impact of early D for mHSPC on subsequent AA/E therapy would greatly aid treatment decision-making and provide useful data to delineate the most appropriate sequence of drugs for a given patient after failure of the chemohormonal regimen. Therefore, in this report we aimed to evaluate the outcomes of first-line AA or E treatment for mCRPC patients selected from three hospitals’ databases and classified by use of D for mHSPC.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

From the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute of Boston, the St Vincent’s Hospital of Sydney, and the Tom Baker Cancer Center of Calgary Institutional Review Board approved databases we retrospectively identified consecutive patients with histologically confirmed and radiologically evaluable mCRPC who had initiated AA or E as first-line treatment for mCRPC between 2014 and 2017. This time frame was selected considering that the chemohormonal regimen was recognized as a valid therapeutic option for mHSPC in 2014. Patients were excluded if they had received AA or E for any earlier stage of disease or had been given any other agent as first-line treatment for mCRPC. The final cohort was classified by previous use of D for mHSPC into 2 groups: ADT+D and ADT alone. The primary endpoints of the study were overall survival (OS) from ADT start and OS from AA/E start, defined as time from ADT for mHSPC and time from first-line AA/E for mCRPC start, respectively, to death from any cause or censored at last follow-up visit. Time to AA/E start, defined as the interval from ADT commencement to initiation of first-line AA/E for mCRPC, was the secondary endpoint. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate the distributions of the endpoints, including median time-to-event and its 95% CI, and the log-rank test was used to compare time-to-event distributions between the two groups. Time of metastatic disease presentation, whether after prior definitive local therapy or newly diagnosed (de-novo), biopsy Gleason score, and follow-up data was collected from medical records.

RESULTS

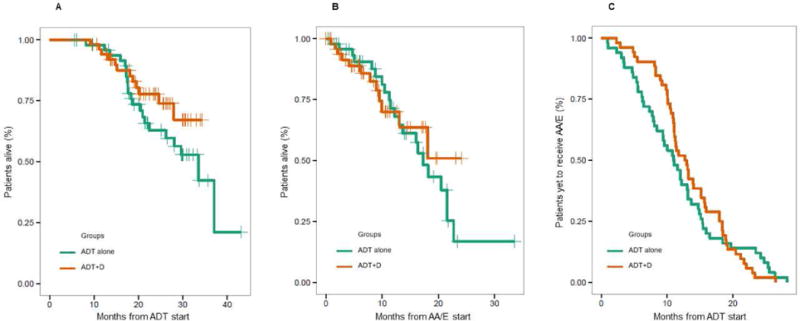

Overall, 102 patients with mCRPC were eligible for this analysis. Fifty-two (51%) had received ADT+D and 50 (49%) ADT alone, for mHSPC. Baseline patient characteristics are described in Table 1. Despite randomization not being part of the study design, the two cohorts were well balanced in terms of prior local therapy/de novo, median follow-up, and distributions of AA and E which were similar also in the total population, 50% vs. 47%, respectively. Most patients had de-novo disease 71% and, of the 53 with available data, 37 had biopsy Gleason score ≥ 8. Median follow-up was only 26.4 (95% CI, 24.0 – 29.9) months due to the chosen eligibility time window. For the same reason, also time to AA/E start was short at 11.0 (95% CI, 8.5 – 13.7) months for the ADT alone cohort and 12.8 (95% CI, 11.1 – 15.7) months for the ADT+D cohort (Table 2). In this regard, no statistically significant difference was observed in time to AA/E start between the two study groups (P=0.7265). Furthermore, the two cohorts did not show any significant difference in OS from ADT start (P=0.2047) or in OS from AA/E start (P=0.6514) (Table 2). In the ADT+D group neither the median survival from ADT start [not yet reached (NR); 95% CI, NR – NR] nor the median OS from AA/E start (NR; 95% CI, 13.1 – NR) had been reached at the time of the analysis. The Kaplan-Meier estimates confirm these findings showing the two study groups with similar survival and time to AA/E start curves, respectively, and not reached median survivals for the chemohormonal cohort (Fig. 1). Notably, OS from ADT start in the ADT alone group at 33.5 (95% CI, 22.4 – NR) months was in line with that of patients with poor prognostic factors, such as high-volume and de novo metastatic disease, as noted in the CHAARTED, LATITUDE and GETUG-AFU15 trials [8,11,12]. In this respect, prostate-cancer deaths in the ADT alone group were 21 vs. 12 in the ADT+D group, after a median follow-up of 29.8 and 24.4 months, respectively (Table 2).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics according to the use of D in addition to ADT for mHSPC

| Characteristics | Total, N = 102 | ADT alone, N = 50 | ADT+D, N = 52 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biopsy Gleason Score, N (%) | ≤ 6 | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) |

| = 7 | 15 (15) | 1 (2) | 14 (27) | |

| ≥ 8 | 37 (36) | 23 (46) | 14 (27) | |

| Missing data | 49 (48) | 25 (50) | 24 (46) | |

| Prior Local Therapy, N (%) | 30 (29) | 15 (30) | 15 (29) | |

| De-novo, N (%) | 72 (71) | 35 (70) | 37 (71) | |

| First-line AA/E, N (%) | AA | 51 (50) | 24 (48) | 27 (52) |

| E | 48 (47) | 23 (46) | 25 (48) | |

| AA+E | 3 (3) | 3 (6) | 0 (0) | |

| Median Follow-up, mo (95% CI) | 26.4 (24.0 – 29.9) | 29.8 (25.1 – 31.4) | 24.4 (21.7 – 27.1) | |

AA = abiraterone acetate; ADT = androgen deprivation therapy; CI = confidence interval; D = docetaxel; E = enzalutamide; mHSPC = metastatic hormone sensitive prostate cancer; mo = months; N = number

Table 2.

Outcomes according to the use of D in addition to ADT for mHSPC

| First-line AA/E |

N (%) | N Deaths (median follow-up mo) |

Median OS from ADT start (95% CI mo) |

P-value | Time to AA/E start (95% CI mo) |

P-value | Median OS from AA/E start (95% CI mo) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADT | 50 (49%) | 21 (29.8) | 33.5 (22.4 – NR) | 0.2047 | 11.0 (8.5 – 13.7) | 0.7265 | 17.3 (13.7 – NR) | 0.6514 |

| ADT+D | 52 (51%) | 12 (24.4) | NR (NR – NR) | 12.8 (11.1 – 15.7) | NR (13.1 – NR) |

AA = abiraterone acetate; ADT = androgen deprivation therapy; CI = confidence interval; D = docetaxel; E = enzalutamide; mo = months; N = number; NR = not yet reached; OS = overall survival

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of OS from ADT start (A), OS from AA/E start (B), and time to AA/E start (C).

DISCUSSION

Although the addition of D to ADT proved to be significantly beneficial for men with mHSPC [6,7], the impact of upfront D on later therapies has not been yet investigated and an optimal treatment sequence for mCRPC has not been defined by well powered prospective trials, even for patients receiving D in the standard setting. In a recent analysis, second-generation hormonal agents AA and E have been reported as the most commonly administered first-line treatment for US men with mCRPC [5]. To our knowledge, this retrospective study is the first to explore the influence of early D on the clinical efficacy of subsequent first-line AA or E for mCRPC, using contemporaneous cohorts of ADT+D and ADT alone pretreated men with mCRPC. It has been theorized that early chemotherapy disposes of AR-independent tumor clones hence favoring efficacy of AR targeting AA/E as first-line treatment for mCRPC [6,10]. On the other hand, a few in vivo and in vitro studies observed cross-resistance between D for mCRPC and subsequent AA or E and partly attributed it to the partially overlapping mechanisms of action of these drugs which interfere with AR signaling pathway and inhibit AR nuclear translocation [13-15]. In the present study, D is used for the hormone-sensitive disease but the treatment sequence is the same hence cross-resistance could arise. However, this report showed that first-line AA or E therapy for mCRPC maintains its activity whether D was used upfront or not. Specifically, there was no statically significant difference in any of the explored outcomes. Nonetheless, it should be noted that in the ADT alone group OS from AA/E start was considerably shorter at 17.3 (95% CI, 13.7 – NR) months than observed with pre-chemotherapy AA and E for mCRPC in the final analyses of their pivotal trials, 34.7 (95% CI, 32.7 – 36.8) and 35.3 (95% CI, 32.2 – NR) months, respectively [16,17]. Furthermore, OS from ADT start was short at 33.5 (95% CI, 22.4 – NR) months and consistent with a population with poor prognostic features [8,11,12]. Patients’ baseline characteristics seem to support this premise since 71% of the total population and 70% of the ADT alone cohort had de novo metastatic disease, and 37 of the 53 patients without missing data and, remarkably, 23 of 25 in the ADT alone cohort had biopsy Gleason score ≥ 8. This is not surprising given the chosen recruitment time window which inevitably determined a short median follow-up and a selection of patients with short time to AA/E start, which were 29.8 (91% CI, 25.1 – 31.4) and 11.0 (95% CI, 8.5 – 13.7) months for the ADT alone cohort, respectively. The present analysis is therefore heavily weighted by the early events which were very similar in both arms even in the pivotal studies that, as a matter of fact, required a longer follow-up for the benefits to be seen. As such, although the median survivals in the ADT+D group were not reached at the time of the analysis, there was no statistically significant difference from the ADT alone group. Yet, prostate cancer deaths were more numerous in the ADT alone cohort compared to the ADT+D cohort, 21 vs. 12 after a median follow-up of 29.8 and 24.4 months, respectively. This finding is visually highlighted by the Kaplan-Meier estimates of OS from ADT start which show a gap between the curves starting after 15 months and quite steadily widening over time in favor of the combination group (Fig. 1A). This also appears to be the case of OS from AA/E start (Fig. 1B). Longer follow-up and possibly larger samples would be needed to confirm this trend. However, despite not reaching a statistically significant difference, men treated with the chemohormonal regimen tended to experience a longer time to AA/E start (Fig. 1C) compared to those treated with ADT alone. Therefore, considering that the two study groups were well balanced with respect to number of patients and clinical and treatment characteristics, we could speculate that patients who received upfront D appear to be faring better with first-line AA or E for mCRPC than patients who received ADT alone, which is consistent with our hypothesis. Larger prospective studies with longer follow-up and better biological and clinical patient characterization would be needed to confidently confirm this hypothesis.

As the chemohormonal regimen is being increasingly administered to the mHSPC population, gathering evidence on the most appropriate sequence of additional treatments after failure of upfront D has become paramount. To the authors’ knowledge, the present analysis is the first to provide useful clinical data to address this issue. Nevertheless, the innate biases of this study including the short median follow-up, small sample size, and retrospective nature represent limitations that prevent generalization of the results. On the other hand, interpreted with caution, this data may aid the physician in the treatment decision-making and reassure him on the use of early D for mHSPC. In fact, our outcomes showed that exposure to upfront D for mHSPC patients with poor prognostic factors, such as de novo metastatic presentation, at least does not reduce efficacy of later AA/E used as first line treatment for mCRPC. This conclusion is supported by the results of the latest post-hoc analysis of the STAMPEDE trial comparing two contemporaneously randomized cohorts of patients treated with ADT+D and ADT+AA, respectively [18]. Despite the limited statistical power and, similar to our study, a short follow-up (approximately 4 years), this report showed that the ADT plus AA significantly extends failure-free survival and progression-free survival compared to the chemohormonal regimen in the mHSPC population. However, OS from randomization did not differ between the two treatment arms. Since most patients progressing after upfront D received AA or E [18], it would appear that the activity of first-line AA or E for mCRPC was at least not diminished by previous use of D, as suggested by our analysis.

Given the heterogeneity of prostate cancer, we deem it unlikely that a single sequence of treatments could provide the best benefit/risk ratio to all mCRPC patients progressing on early D. An individualized therapeutic approach which takes into account the diverse tumor biological and molecular features, patient clinical characteristics, and prognostic and predictive biomarkers would be required to maximize survival. However, while the continuous advances in the knowledge of tumor biology and in the development of biotechnologies pave the way towards a future of precision medicine, clinical reports addressing treatment sequencing questions can provide the clinician with useful indications to make evidence-based decisions.

CONCLUSION

Despite the shortcomings of this analysis, we deem our data clinically relevant as they suggest that, in a cohort of patients with short median follow-up and time to AA/E start, first-line AA/E treatment for mCRPC maintains its efficacy regardless of previous use of D for mHSPC.

Clinical Practice Points.

Abiraterone acetate (AA) and enzalutamide (E) are the most frequently used first-line treatment for metastatic CRPC (mCRPC).

In mCRPC patients the efficacy of AA/E seems to be similar regardless of previous use of docetaxel (D) for metastatic hormone sensitive prostate cancer (mHSPC).

Larger prospective studies with longer follow-up and better biological and clinical patient characterization are warranted to confirm these findings.

These results may aid the physician in the treatment decision-making and reassure him on the use of early D for mHSPC.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest

Philip W. Kantoff received compensation for scientific advisory board/consulting for Astellas, Bayer, Bellicum, BIND Biosciences, BN Immunotherapeutics, DRGT, Ipsen Pharmaceuticals, Janssen, Metamark, Merck, MTG Therapeutics, New England Research Institutes, Omnitura, OncoCellMDX, Progenity, Sanofi, Tarveda Therapeutics, Thermo Fisher Scientific; he has investment interests in Bellicum, DRGT, Metamark, Tarveda Therapeutics; and he is on data safety monitoring board of Genetech/Roche, Merck, Oncogenex. LCH reports compensation for consulting/advisory role at Dendreon, Genentech, KEW Group, Medivation/Astellas, Pfizer, Theragene; and institutional research funding from Bayer, Dendreon, Genentech/Roche, Medivation/Astellas, Sotio, Takeda, BMS; Travel, Accommodations, and Expenses from Sanofi. Mary-Ellen Taplin reports personal fees for attending advisory boards for Janssen and Medivation; and receives research funding from Janssen and Medivation. Daniel Y.C. Heng declares compensation for advisory board for Astellas and Janssen. Christopher J. Sweeney reports consulting with compensation for Astellas, Bayer, Genentech, Janssen, Pfizer, Sanofi; and received research funding from Astellas, Janssen, Sotio, Sanofi. Edoardo Francini declares that he has no conflict of interest, Steven Yip declares that he has no conflicts of interest, Shubidito Ahmed declares that he has no conflict of interest, Haocheng Li declares that he has no conflict of interest, Luke Ardolino declares that he has no conflict of interest, Carolyn P. Evan declares that she has no conflict of interest, Marina Kaymakcalan declares that she has no conflict of interest, Grace K. Shaw declares that she has no conflict of interest, Nimira S. Alimohamed declares that he has no conflict of interest, Anthony M. Joshua declares that he has no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Huggins C, Stevens RE, Jr, Hodges CV. Studies on prostatic cancer: II. The effects of castration on advanced carcinoma of the prostate gland. Arch Surg. 1941;43(2):209–223. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tannock IF, de Wit R, Berry WR, Horti J, Pluzanska A, Chi KN, Oudard S, Théodore C, James ND, Turesson I, Rosenthal MA, Eisenberger MA, TAX 327 Investigators Docetaxel plus prednisone or mitoxantrone plus prednisone for advanced prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1502–1512. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Petrylak DP, Tangen CM, Hussain MH, Lara PN, Jr, Jones JA, Taplin ME, Burch PA, Berry D, Moinpour C, Kohli M, Benson MC, Small EJ, Raghavan D, Crawford ED. Docetaxel and estramustine compared with mitoxantrone and prednisone for advanced refractory prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1513–1520. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shiota M, Yokomizo A, Fujimoto N, Kuruma H, Naito S. Castration-resistant prostate cancer: novel therapeutics pre- or post-taxane administration. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2013;13:444–459. doi: 10.2174/15680096113139990078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flaig TW, Potluri RC, Ng Y, Todd MB, Mehra M. Treatment evolution for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer with recent introduction of novel agents: retrospective analysis of real-world. Cancer Med. 2016;5:182–191. doi: 10.1002/cam4.576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sweeney CJ, Chen YH, Carducci M, Liu G, Jarrard DF, Eisenberger M, Wong YN, Hahn N, Kohli M, Cooney MM, Dreicer R, Vogelzang NJ, Picus J, Shevrin D, Hussain M, Garcia JA, DiPaola RS. Chemohormonal Therapy in Metastatic Hormone-Sensitive Prostate Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:737–746. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1503747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.James ND, Sydes MR, Clarke NW, Mason MD, Dearnaley DP, Spears MR, Ritchie AW, Parker CC, Russell JM, Attard G, de Bono J, Cross W, Jones RJ, Thalmann G, Amos C, Matheson D, Millman R, Alzouebi M, Beesley S, Birtle AJ, Brock S, Cathomas R, Chakraborti P, Chowdhury S, Cook A, Elliott T, Gale J, Gibbs S, Graham JD, Hetherington J, Hughes R, Laing R, McKinna F, McLaren DB, O’Sullivan JM, Parikh O, Peedell C, Protheroe A, Robinson AJ, Srihari N, Srinivasan R, Staffurth J, Sundar S, Tolan S, Tsang D, Wagstaff J, Parmar MK, STAMPEDE investigators Addition of docetaxel, zoledronic acid, or both to first-line long-term hormone therapy in prostate cancer (STAMPEDE): survival results from an adaptive, multiarm, multistage, platform randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;387:1163–1177. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01037-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fizazi K, Tran NP, Fein L, Matsubara N, Rodriguez-Antolin A, Alekseev BY, Özgüroğlu M, Ye D, Feyerabend S, Protheroe A, De Porre P, Kheoh T, Park YC, Todd MB, Chi KN, LATITUDE Investigators Abiraterone plus prednisone in metastatic, castration-sensitive prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:352–360. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1704174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.James ND, de Bono JS, Spears MR, Clarke NW, Mason MD, Dearnaley DP, Ritchie AWS, Amos CL, Gilson C, Jones RJ, Matheson D, Millman R, Attard G, Chowdhury S, Cross WR, Gillessen S, Parker CC, Russell JM, Berthold DR, Brawley C, Adab F, Aung S, Birtle AJ, Bowen J, Brock S, Chakraborti P, Ferguson C, Gale J, Gray E, Hingorani M, Hoskin PJ, Lester JF, Malik ZI, McKinna F, McPhail N, Money-Kyrle J, O’Sullivan J, Parikh O, Protheroe A, Robinson A, Srihari NN, Thomas C, Wagstaff J, Wylie J, Zarkar A, Parmar MKB, Sydes MR, STAMPEDE Investigators Abiraterone for Prostate Cancer Not Previously Treated with Hormone Therapy. New Eng J Med. 2017;377:338–351. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1702900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahmed M, Li LC. Adaptation and clonal selection models of castration-resistant prostate cancer: current perspective. Int J Urol. 2013;20:362–371. doi: 10.1111/iju.12005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sweeney CJ, Chen YH, Liu G, Carducci M, Jarrard D, Eisenberger M, Wong YN, Patrick-Miller L, Hahn N, Kohli M, Cooney M, Dreicer R, Vogelzang NJ, Picus J, Shevrin D, Hussain M, Garcia J, Dipaola R. Long term efficacy and QOL data of chemohormonal therapy (C-HT) in low and high volume hormone naïve metastatic prostate cancer (PrCa): E3805 CHAARTED trial. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(6):243–265. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw372.4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gravis G, Boher JM, Joly F, Soulié M, Albiges L, Priou F, Latorzeff I, Delva R, Krakowski I, Laguerre B, Rolland F, Théodore C, Deplanque G, Ferrero JM, Culine S, Mourey L, Beuzeboc P, Habibian M, Oudard S, Fizazi K, GETUG Androgen Deprivation Therapy (ADT) Plus Docetaxel Versus ADT Alone in Metastatic Non castrate Prostate Cancer: Impact of Metastatic Burden and Long-term Survival Analysis of the Randomized Phase 3 GETUG-AFU15 Trial. Eur Urol. 2016;70:256–262. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nadal R, Zhang Z, Rahman H, Schweizer MT, Denmeade SR, Paller CJ, Carducci MA, Eisenberger MA, Antonarakis ES. Clinical activity of enzalutamide in docetaxel-naïve and docetaxel-pretreated patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. The Prostate. 2014;74:1560–1568. doi: 10.1002/pros.22874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Soest RJ, van Royen ME, de Morrée ES, Moll JM, Teubel W, Wiemer EA, Mathijssen RH, de Wit R, van Weerden WM. Cross-resistance between taxanes and new hormonal agents abiraterone and enzalutamide may affect drug sequence choices in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:3821–3830. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoshi S, Numahata K, Ono K, Yasuno N, Bilim V, Hoshi K, Amemiya H, Sasagawa I, Ohta S. Treatment sequence in castration-resistant prostate cancer: A retrospective study in the new anti-androgen era. Mol Clin Oncol. 2017;7:601–603. doi: 10.3892/mco.2017.1361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ryan CJ, Smith MR, Fizazi K, Saad F, Mulders PF, Sternberg CN, Miller K, Logothetis CJ, Shore ND, Small EJ, Carles J, Flaig TW, Taplin ME, Higano CS, de Souza P, de Bono JS, Griffin TW, De Porre P, Yu MK, Park YC, Li J, Kheoh T, Naini V, Molina A, Rathkopf DE, COU-AA-302 Investigators Abiraterone acetate plus prednisone versus placebo plus prednisone in chemotherapy-naive men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (COU-AA-302): final overall survival analysis of a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:152–160. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)71205-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beer TM, Armstrong AJ, Rathkopf D, Loriot Y, Sternberg CN, Higano CS, Iversen P, Evans CP, Kim CS, Kimura G, Miller K, Saad F, Bjartell AS, Borre M, Mulders P, Tammela TL, Parli T, Sari S, van Os S, Theeuwes A, Tombal B. Enzalutamide in Men with Chemotherapy-naïve Metastatic Castration-resistant Prostate Cancer: Extended Analysis of the Phase 3 PREVAIL Study. Eur Urol. 2017;71:151–154. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.07.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sydes MR, Mason MD, Spears MR, Clarke NW, Dearnaley D, Ritchie AWS, Russell M, Gilson C, Jones R, de Bono J, Gillessen S, Millman R, Tolan S, Wagstaff J, Chowdhury S, Lester J, Sheehan D, Gale J, Parmar MK, James ND. Adding abiraterone acetate plus prednisolone (AAP) or docetaxel for patients (pts) with high-risk prostate cancer (PCa) starting long-term androgen deprivation therapy (ADT): directly randomised data from STAMPEDE ( NCT00268476) Ann Oncol. 2017;28(5):605–649. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx440. [DOI] [Google Scholar]