Abstract

Radiation induced morphea (RIM) is an increasingly common complication of radiation treatment for malignancy as early detection has made more patients eligible for non-surgical treatment options. In many cases, the radiation oncologist is the first person to learn of the initial skin changes, often months before a dermatologist sees them. In this paper we present a breast cancer patient who developed a rare bullous variant of RIM, which delayed her diagnosis and subsequent treatment. It is imperative to diagnose RIM early as it carries significant morbidity and permanent deformity if left untreated. The lesions typically present within 1 year of radiation therapy and extend beyond the radiated field. RIM is often mistaken for radiation dermatitis or cellulitis. Bullae, when present, are often hemorrhagic in appearance, which can serve as another clinical clue. It is important to refer these patients for a full gynecologic exam as there can be concurrent anogenital lichen sclerosus et atrophicus which is both debilitating and carries a long term risk for squamous cell carcinoma. Treatment with systemic agents is often necessary, and can be managed by a dermatologist. The most proven regimen in the literature appears to be methotrexate, with our without concurrent narrow band UVB phototherapy.

Keywords: Bullous morphea, Lichen sclerosus, Radiation, Breast cancer

1. Case

A 57 year Caucasian woman presented to our dermatology clinic for a new rash on her right breast. Five months prior, she had completed radiation therapy for invasive ductal carcinoma of the right breast. She received 45 Gy over 25 fractions to the whole right breast and an additional boost of 16 Gy over 8 fractions to the surgical bed (status-post segmental mastectomy). Her left breast was not irradiated at any time, and she had an uneventful radiation course. At her initial examination, there was a single tense bulla within a tender erythematous plaque on the right medial breast (Fig. 1). There was trace lymphedema of the right breast and arm as well, which had been present and unchanged since her initial surgery. Radiation-induced bullous pemphigoid was considered, but skin biopsy with direct immunofluorescence was negative. The patient was empirically treated with dicloxacillin for possible bullous bacterial soft tissue infection, though suspicion was low. Her breast surgeon attributed the bullae to chest wall lymphedema and she was referred to physical therapy.

Fig. 1.

Initial presentation of rash on the right breast.

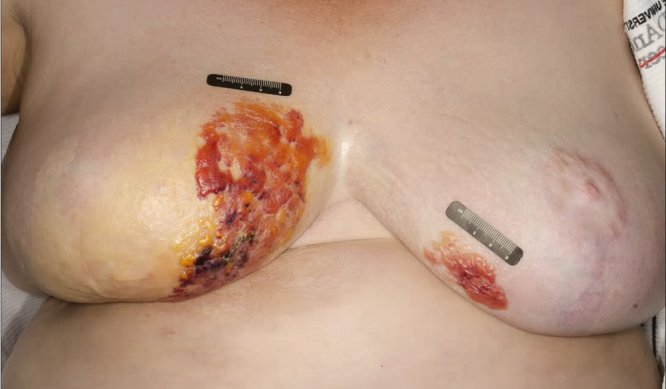

Five months later the patient returned with interval worsening of her symptoms and involvement of both breasts. Examination showed multiple hemorrhagic bullae on the medial breasts, as well as new regions of induration and shiny white sclerosis with overlying skin atrophy. A lilac-colored rim of inflammation outlined the sclerotic regions (Fig. 2). Skin biopsies from both breasts showed histologic features classic for bullous lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (LS&A) in the superficial dermis and morphea in the deep dermis. The patient was started on a 20-day prednisone taper starting at 60 mg and then transitioned to a topical regimen of clobetasol 0.05% cream twice daily. At her 2 month follow up she reported noticeable softening of the sclerotic areas and reduced discomfort (Fig. 3). She subsequently developed new areas of breast involvement and a second course of prednisone was initiated with marked improvement. She also had concomitant vulvar LS&A managed with topical steroids.

Fig. 2.

Worsening of rash with bilateral breast involvement 5 months after initial presentation.

Fig. 3.

Post-treatment with prednisone taper and clobetasol cream.

2. Discussion

Morphea and LS&A are both inflammatory disorders of the skin, with morphea favoring deeper tissue planes (reticular dermis, subcutis) and LS&A favoring the more superficial papillary dermis and overlying epidermis. Morphea is more commonly observed on the trunk whereas LS&A favors the anogenital region, however extragenital forms exist as well and can be clinically indistinct from morphea. The two conditions both present with a violaceous halo of inflammation around sites of evolving sclerosis and later adopt a shiny, white appearance centrally. There is debate as to whether morphea and LS are distinct entities or represent ends of a common spectrum,3, 4, 5, 6 but they are both considered autoimmune phenomena. In susceptible patients, radiation is one of the known triggers; it is thought that radiation induces a Th2 immune profile, with up-regulation of IL-4 and TGF-beta leading to increased fibroblast activity and sclerosis.1, 2

Since 1989, there are approximately 88 cases of radiation-induced morphea (RIM) reported in the literature. The majority of cases were female breast cancer patients, but it can affect males and other anatomic sites as well. Symptoms usually develop within 1 year of radiation therapy, and there is no apparent link between the radiation regimen (dose, fractionation, boost) and risk for developing RIM.2, 15 The clinical course is biphasic with an initial inflammatory phase followed by a fibrotic phase. The inflammatory phase is often mistaken for cellulitis, acute radiation dermatitis, mastitis, or inflammatory breast cancer.1, 2 The later fibrotic phase can be mistaken for chronic radiation dermatitis or post-irradiation fibrosis. A helpful clue is that RIM often extends beyond the radiated field, which is not true of other radiation-induced dermatoses.2, 15

To our knowledge, there is only one other reported case of RIM with bullous formation, however the temporal course was slightly different as the patient had an initial biopsy of RIM and three years later developed bullae.7 In contrast, our patient presented with established bullae early in her disease course. The bullae later became hemorrhagic, which has also been reported in the literature with bullous morphea,12, 13, 14 and may serve as a clue in distinguishing bullous morphea/LS&A from other bullous dermatoses. It has been postulated that the bullae are traumatic in origin,12 and our patient specifically cited bothersome friction from her bra.

There have been various papers published on the co-existence of morphea and LS&A,3, 8, 9, 11 but there is little published on RIM/LS&A overlap. One series reviewed 5 cases of RIM and found histologic evidence of concurrent LS&A in 2 patients.2 Another study demonstrated a high incidence of genital LS&A in patients with morphea elsewhere. Interestingly, only 20% of patients reported pruritus, and 0% of patients reported any genital symptoms whatsoever if not directly questioned.10 While this study was a review of morphea in general (not radiation-induced), our patient was later found to have vulvar LS&A after her initial RIM diagnosis. Chronic, untreated anogenital LS&A can have significant morbidity including loss of the labia minora, fusion of the clitoral hood, dyspareunia, and development of squamous cell carcinoma within the affected site. Accordingly, a genital exam should be part of the standard exam for patients with RIM.

The response to treatment for RIM/LS&A is highly variable. A multicenter study from 2017 reviewed 22 patients with RIM and their responses to various treatment regimens. The data showed that patients treated with systemic agents or phototherapy were four times more likely to achieve a marked response (defined as >75% improvement) compared to intralesional or topical agents. Methotrexate with or without narrow bandUVB produced a marked improvement in 4/4 patients within the cohort, making it the most successful combination in this particular study. There were isolated successes seen with pentoxifylline, oral calcitriol, colchicine, and penicillamine as well. Other options reported in the literature include systemic antibiotics, topical and systemic steroids, topical calcineurin inhibitors, phototherapy (especially UVA1), topical vitamin D analogs, imiquimod, cyclosporine, mycophenolate mofetil, and extracorporeal photopheresis.1, 2 In general, immunosuppressive therapy is less desirable as nearly all patients with RIM have a history of prior malignancy, and ultra violet therapy carries the risk of skin cancer. Also, many of the proposed treatments require frequent clinical and laboratory monitoring for side effects.

In closing, the goal of this case report was to present an unusual presentation of a known complication of radiation therapy. It has been reported that approximately 90% of all breast cancer patients undergoing radiation therapy will develop some cutaneous sequelae related to their treatment,1, 2 and through improved screening more breast cancer patients are eligible for treatment with breast-conserving surgeries and adjuvant radiation. The diagnosis of radiation induced bullous morphea/lichen sclerosus et atrophicus may be difficult, and must be distinguished from chronic radiation dermatitis, infection, and lymphedema. However, as long as providers remain vigilant and keep RIM on their differential diagnosis, then our patients will continue to benefit from early referral, diagnosis, and treatment.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Financial disclosure

None declared.

References

- 1.Dyer B.A., Hodges M.G., Mayadev J.S. Radiation-induced morphea: an under recognized complication of breast irradiation. Clin Breast Cancer. 2016;16(August (4)):e141–e143. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2016.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spalek M., Jonska-Gmyrek J., Gałecki J. Radiation-induced morphea – a literature review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29(February (2)):197–202. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Uitto J., Santa Cruz D.J., Bauer E.A., Eisen A.Z. Morphea and lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. Clinical and histopathologic studies in patients with combined features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1980;3:271–279. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(80)80190-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Connelly M.G., Winkelmann R.K. Coexistence of lichen sclerosus, morphea, and lichen planus. Report of four cases and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;12:844–851. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(85)70106-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Winer L.H. Elastic fibers in unusual dermatoses. AMA Arch Derm. 1955;71:338–348. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1955.01540270050005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patterson J.A., Ackerman A.B. Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus is not related to morphea. A clinical and histologic study of 24 patients in whom both conditions were reputed to be present simultaneously. Am J Dermatopathol. 1984;6:323–335. doi: 10.1097/00000372-198408000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trattner A., David M., Sandbank M. Bullous morphea: a distinct entity? Am J Dermatopathol. 1994;16(August (4)):414–417. doi: 10.1097/00000372-199408000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bergfeld W.F., Lesowitz S.A. Lichen sclerosus at atrophicus. Arch Dermatol. 1970;101:247–248. doi: 10.1001/archderm.101.2.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tremaine R., Adam J.E., Orizaga M. Morphea coexisting with lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. Int J Dermatol. 1990;29:486–489. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1990.tb04840.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lutz V., Frances C., Bessis D. High frequency of genital lichen sclerosus in a prospective series of 76 patients with morphea: toward a better under- standing of the spectrum of morphea. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:24–28. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2011.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kreuter A., Wischnewski J., Terras S., Altmeyer P., Stücker M., Gambichler T. Coexistence of lichen sclerosus and morphea: a retrospective analysis of 472 patients with localized scleroderma from a German tertiary referral center. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67(December (6)):1157–1162. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fernandez-Flores A., Gatica-Torres M., Tinoco-Fragoso F., García-Hidalgo L., Monroy E., Saeb-Lima M. Three cases of bullous morphea: histopathologic findings with implications regarding pathogenesis. J Cutan Pathol. 2015;42:144–149. doi: 10.1111/cup.12418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tudino M.E., Wong A.K. Bullous lichen sclerosus et atrophicus on the palms and wrists. Cutis. 1984;33:475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tosti A., Melino M., Bardazzi F. Hemorrhagic bullous lesions in morphea. Cutis. 1989;44:118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frutcher R., Kurtzman D.J.B., Mazori D.R. Characteristics and treatment of postirradiation morphea: a retrospective multicenter analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76(January (1)):19–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.08.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]