Food insecurity, defined as a household condition involving the “limited or uncertain availability of nutritionally adequate and safe foods or limited or uncertain ability to acquire acceptable foods in socially acceptable ways”,1 affects one out of eight U.S. households2 and exists in every county across the nation.3 Dietetics practitioners working in clinical as well as community settings will likely encounter clients affected by food insecurity during their career. The Nutrition Care Process (NCP) is a systematic problem-solving method to guide critical thinking and evidence-based decision making for addressing nutrition-related problems experienced by individuals, groups, and communities, including food insecurity.4 Beginning with an overview of food insecurity, including its nutrition implications and screening options for at-risk populations, this article describes how dietetics practitioners can use food insecurity-informed critical thinking skills during each step of the NCP. Two case examples of dietetics practitioners implementing these considerations in their daily practice with individuals and communities are presented to illustrate these applications, followed by dietetics-oriented action items to support the delivery of food insecurity-informed nutrition care.

Food Insecurity: Nutritional Implications and Screening Options for At-Risk Populations

Nutritional Implications

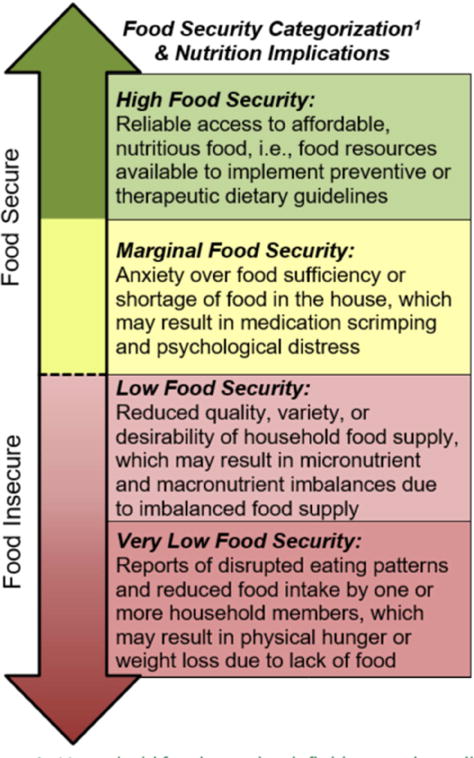

Food security status operates on a spectrum to describe quality and quantity of household food supply, which is subsequently categorized as high, marginal, low, and very low food security; the latter two conditions are classified as food insecure (Figure 1).2 The health and nutrition-related consequences of food insecurity on household members are often cumulative as food insecurity severity increases. Household food insecurity is linked to many nutrition-related outcomes due to its effects on dietary quality and quantity,5 associations with mental and physical health,6 and impacts disease self-management capabilities of affected members.7 These outcomes may contribute to disability, which can further reduce household resources due to health care costs and adult unemployment, leading to a vicious cycle of compromised food supply.8 A brief overview of select nutrition implications for adult- and child-household members affected by household food insecurity is presented below.

Figure 1.

Household food security definitions and possible nutrition implications associated with characteristics of household food supply. Note that nutrition implications are cumulative as food security becomes compromised, beginning with marginal food security.1 Adapted from: Bickel G, Nord M, Price C, Hamilton W, Cook J. Guide to measuring household food security, Revised 2000. Alexandria VA: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service; 2000.

Adults

Dietary patterns of adults experiencing household food insecurity reflect low consumption of fruits and vegetables, dairy products, iron, zinc, vitamin E, and vitamin B6,9, with common serum deficiencies including iron, vitamin B12, calcium, magnesium, vitamin A, vitamin C, carotenoids, and folate.10 These deficiencies can result in anemia, low bone density, and general poor health. Food insecurity is inconsistently associated with obesity among women, which may result from the metabolic consequences of cyclical food restriction and consumption of energy-dense foods as a strategy to lower food costs.11–13 Food insecurity may contribute to the development of metabolic syndrome14 and is associated with many chronic diseases,15 such as type 2 diabetes and hypertension.16 Household food insecurity can also compromise disease self-management abilities, including glycemic control among diabetics.7,17

Children and adolescents

Iron deficiency disproportionately affects children living in food insecure households, which can impair motor skill, language and cognitive development, socioemotional state, attentiveness, and school performance.18 Household food insecurity is associated with greater odds of child hospitalization and fair to poor health status.19 Children who live in households with very low food security at any point between birth and toddler years, especially if they are born at a low birth weight, have greater odds of obesity before kindergarten than their food secure peers.20 Furthermore, repeated episodes of hunger in childhood may affect future chronic disease development.18 Similar to adult household members, teenagers may sometimes restrict or go without food to protect younger siblings.21 Without proper nutrition intake, food insecurity undermines adolescent physical and emotional growth, stamina, academic achievement and job performance.21

Food insecurity screening options for at-risk populations

Nutrition screening identifies patients who may need special interventions and should be informed by the risk characteristics of the population being screened.22 While screening is most often implemented by individuals outside of the nutrition services team, dietetics practitioners should provide input on the selection of screening questions and referral procedures.22 Food insecurity screening considerations for at-risk populations are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Food Insecurity Screening Considerations for the Dietetics Practitioner

| Food Insecurity Screening | ||

|---|---|---|

| Who can screen? | Who should be screened? | Possible actions |

|

Populations at higher risk for food insecurity

include:

|

|

Coleman-Jensen A, Rabbitt MP, Gregory CA, Singh A. Household food security in the United States in 2015. United States Department of Agriculture; 2016. Economic Research Report 215;

Gundersen C. Measuring the extent, depth, and severity of food insecurity: an application to American Indians in the USA. J Popul Econ. 2008;21(1):191–215;

Coleman-Jensen A, Nord M. Food insecurity among households with working-age adults with disabilities. USDA-ERS; 2013;

Tarasuk V, Mitchell A, McLaren L, McIntyre L. Chronic physical and mental health conditions among adults may increase vulnerability to household food insecurity. J Nutr. 2013;143(11):1785–1793

Researchers typically use the 10-item U.S. Adult Food Security Survey Module that can include an additional 8 items for assessing households with children;2 however, shorter screening options are available for clinical and community practice settings. The American Academy of Pediatrics23 and the American Association of Retired Persons24 endorse a two-question screening tool with ≥97% sensitivity and ≥74% specificity for household food insecurity. Answering “often true” or “sometimes true” to either question below indicates potential household food insecurity:25

Within the past 12 months, we worried whether our food would run out before we got money to buy more. □ Often True □ Sometimes True □ Never True

Within the past 12 months, the food we bought just didn’t last and we didn’t have money to buy more. □ Often True □ Sometimes True □ Never True

When potential household food insecurity is identified, screening protocols should include follow-up procedures for client linkage to food assistance programs and an additional referral to a qualified dietetics practitioner when household food insecurity may be contributing to nutrition-related health status. The dietetics practitioner can then proceed with assessing nutritional risk in the context of food insecurity as the first step of the NCP, followed by diagnosis, intervention, and monitoring/evaluation.4 Critical thinking questions and considerations related to the delivery of care for food insecure clients for each step of the NCP are detailed in Table 2.

Table 2.

The Nutrition Care Process (NCP): Step-by-Step Critical Thinking Questions and Considerations when Delivering Care to Clients Living in Food Insecure Households

| NCP Step 1: Nutrition Assessment | |

|---|---|

| Critical Thinking Questions and Additional Considerations for Each Assessment Domain | Possible Indicators of a Nutrition Problem with Food Insecurity-related Etiology (Non-Exhaustive List) |

|

Food- and nutrition related

history Food and nutrient intake, food and nutrient administration, medication, complementary/alternative medicine use, knowledge/beliefs, food and supplies availability, physical activity, nutrition quality of life1

|

Food and Nutrient Intake

(1) Energy intake (1.1.1)

Food and Knowledge/Skill (4.1) Beliefs and attitudes (4.2)

Adherence (5.1)

Food/nutrition program participation (6.1)

Factors affecting access to physical activity (7.4)

Nutrition quality of life (8.1) |

|

Anthropometric

Measurements Height, weight, body mass index (BMI), growth pattern indices/percentile ranks, and weight history1

|

Body composition/growth/weight history (1.1)

|

|

Biochemical Data, Medical Tests, and

Procedures Lab data (e.g., electrolytes, glucose) and tests (e.g., gastric emptying time, resting metabolic rate)1

|

Glucose/endocrine profile (1.5)

|

|

Nutrition-focused physical examination

findings Physical appearance, muscle and fat wasting, swallow function, appetite, and affect1

|

Nutrition-Focused Physical Findings (1.1)

|

|

Client

history Personal history, medical/health/family history, treatments and complementary/alternative medicine use, and social history1

|

Personal History

(1) Personal data (1.1)

Patient/client or family nutrition-oriented medical/health history (2.1)

|

| NCP Step 2: Nutrition Diagnosis | |

| Critical Thinking Questions and Additional Considerations related to Terminology and Documentation of Nutrition Problem(s) | Possible Diagnoses with Food Insecurity-related Etiology (Non-Exhaustive List) |

|

Intake Too much or too little of a food or nutrient compared to actual or estimated needs1

|

Energy Balance (1)

|

|

Clinical Nutrition problems that relate to medical or physical conditions1

|

Biochemical (2)

|

|

Behavioral-Environmental Knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, physical environment, access to food, or food safety1

|

Knowledge and Beliefs (1)

|

| Step 3: Nutrition Intervention | |

| Critical Thinking Questions and Additional Considerations related to Domains | Possible Interventions to Address Food Insecurity-related Problem Etiology or Signs/Symptoms (Non-Exhaustive List) |

|

Food and Nutrient

Delivery Individualized approach for food/nutrient provision.1

|

Meals and Snacks (1)

Vitamin and Mineral Supplement Therapy (3.2)

|

|

Nutrition

Education Formal process to instruct or train patients/clients in a skill or to impart knowledge to help patients/clients voluntarily manage or modify food, nutrition and physical activity choices and behavior to maintain or improve health.1

|

Nutrition Education – Content

(1)

|

|

Nutrition

Counseling A supportive process, characterized by a collaborative counselor–patient/client relationship to establish food, nutrition and physical activity priorities, goals, and individualized action plans that acknowledge and foster responsibility for self-care to treat an existing condition and promote health.1

|

Strategies (2)

|

|

Coordination of Nutrition

Care Consultation with, referral to, or coordination of nutrition care with other providers, institutions, or agencies that can assist in treating or managing nutrition-related problems.1

|

Collaboration and Referral of Nutrition

Care (1) Collaboration with other nutrition professionals

|

| Step 4: Monitoring and Evaluation | |

| Special Considerations for Food Insecure Populations | |

Monitor outcomes

| |

Measure outcomes

| |

Evaluate outcomes

| |

Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Nutrition Terminology Reference Manual (eNCPT): Dietetics language for nutrition care. http://ncpt.webauthor.com/. Accessed August 9, 2017;

Kirkpatrick SI, Tarasuk V. Food insecurity is associated with nutrient inadequacies among Canadian adults and adolescents. J Nutr. 2008;138(3):604–612;

Hanson KL, Connor LM. Food insecurity and dietary quality in US adults and children: a systematic review. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;100(2):684–692;

Muirhead V, Quinonez C, Figueiredo R, Locker D. Oral health disparities and food insecurity in working poor Canadians. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2009;37(4):294–304;

Coleman-Jensen A, Rabbitt MP, Gregory CA, Singh A. Household food security in the United States in 2015. United States Department of Agriculture;2016. Economic Research Report 215;

Gunderson C, Dewey A, Crumbaugh AS, et al. Map the meal gap 2016. Chicago, IL: Feeding America; 2016;

Cutler-Triggs C, Fryer GE, Miyoshi TJ, Weitzman M. Increased rates and severity of child and adult food insecurity in households with adult smokers. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162(11):1056–1062;

Coleman-Jensen A, Nord M. Food insecurity among households with working-age adults with disabilities. 2013;

Seligman HK, Laraia BA, Kushel MB. Food insecurity is associated with chronic disease among low-income NHANES participants. Journal Nutr. 2010;140(2):304–310;

Anema A, Weiser SD, Fernandes KA, et al. High prevalence of food insecurity among HIV-infected individuals receiving HAART in a resource-rich setting. AIDS Care. 2011;23(2):221–230;

Hanson KL, Olson CM. Chronic health conditions and depressive symptoms strongly predict persistent food insecurity among rural low-income families. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2012;23(3):1174–1188;

Leung CW, Epel ES, Ritchie LD, Crawford PB, Laraia BA. Food insecurity is inversely associated with diet quality of lower-income adults. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2014;114(12):1943–1953.e1942;

White JV, Guenter P, Jensen G, Malone A, Schofield M. Consensus Statement: Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics and American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2012;36(3):275–283;

Satter E. Hierarchy of Food Needs. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2007;39(5, Supplement):S187–S188.

Applying the Nutrition Care Process when Food Insecurity is Identified

Assessment

Nutrition assessment is an ongoing process of collecting and analyzing client data in order to inform the nutrition diagnosis.4 When the dietetics practitioner identifies a client who is at risk for food insecurity through positive screening results, the practitioner can apply their knowledge of food insecurity’s possible psychosocial, behavioral, nutritional and physical health consequences to inform data collection during the five domains of nutrition assessment (Table 2). To guide critical thinking, the dietetics practitioner should first determine the severity of household food insecurity to then consider how the degree of compromised food supply may be affecting food intake (Figure 1). Probing questions during the patient interview can be used to assess how food insecurity is affecting level of food intake, meal patterns, or other eating behaviors. If the dietetics practitioner suspects the intake domain is being affected, he or she can then explore remaining assessment domains to determine if data are clustering to reflect food insecurity as an underlying cause for nutrition problem(s).

Diagnosis

Nutrition diagnosis identifies the nutrition problem to be addressed by the dietetics practitioner through nutrition intervention and is organized into a statement with the following structure: “Problem” [related to] “Etiology” [as evidenced by] “Signs/Symptoms” (PES).4 By gathering information during the client interview to assess how the degree of household food insecurity is affecting dietary intake or clinical domain nutrition problems, the dietetics practitioner can effectively identify how food insecurity is functioning as a cause or contributing risk factor of the nutrition problem in the “etiology” statement. An example food insecurity-informed nutrition diagnosis from the intake domain is as follows:

Inconsistent carbohydrate intake related to erratic food availability and cyclical food restriction, as evidenced by estimated total carbohydrate intake ranging between 15 and 90 grams per meal and glucose logs demonstrating frequent episodes of hypo- and hyperglycemia.

If no intake or clinical domain nutrition problem is identified, yet food insecurity is suspected to be contributing to nutritional risk, then a nutrition problem from to the “food safety and access domain” can be used. For example:

Limited access to food related to recent loss of financial resources and ineligibility for federal nutrition assistance programs as evidenced by low supply of food in the home.

Example food insecurity-related diagnoses from each of the three diagnosis domains are listed in Table 2.

Intervention

A nutrition intervention is designed “to resolve or improve the nutrition diagnosis or nutrition problem” and its selection should be informed by the etiology of the problem, whenever possible.4 Since food insecurity results from poor food access among other factors, interventions usually include coordination of nutrition care to facilitate linkage to food assistance or other financial resources, but can also span food and nutrient delivery, nutrition education, and nutrition counseling (Table 2). Planning interventions in a multi-staged design by first prioritizing stabilization of household food supply and limiting nutrition education to survival information, followed by the subsequent establishment of long-term behavior change goals, will likely help improve the client’s ability to adhere to nutrition recommendations.

Monitoring and Evaluation

Nutrition monitoring and evaluation aims to quantify client progress toward resolving the nutrition diagnosis through the achievement of intervention-related goals.4 Thus, outcomes for monitoring and evaluation are chosen based on the nutrition diagnosis and intervention.4 Example outcomes for food insecure clients may include food assistance program participation and satisfaction, improvement in quality and quantity of food intake according to nutrition prescription, improvements in body composition, and improvements in laboratory values related to nutritional status and disease management. Special considerations for food insecure populations during monitoring and evaluation are described in Table 2.

Registered dietitian nutritionists at work: Applying the NCP for the care of food insecure populations in individual and community-based settings

The NCP can be applied to individuals, groups, and communities affected by food insecurity.4 The following case studies illustrate how dietetics professionals can effectively deliver food-insecurity informed care to at-risk populations at the individual and community-levels.

Tulsa CARES: Nutrition Assistance for Individuals with HIV

Tulsa CARES is a non-profit organization in Tulsa, Oklahoma, delivering social services, including mental health, housing, health care navigation, care coordination, and nutrition, to people affected by HIV/AIDS.26 Staffed by a registered dietitian nutritionist (RDN), nutrition and dietetic technician, registered (NDTR), and certified dietary manager, the Tulsa CARES nutrition program provides disease-appropriate groceries, prepared meals, and nutrition education to over 300 clients annually. Approximately two-thirds (67%) of clients served annually are food insecure. Conversations with Tulsa CARES dietitian, Melissa Cejda, MHA, RDN/LD, CDE (March 2017), informed this program spotlight.

As the program’s RDN, Cejda partners with local HIV healthcare providers to accept external MNT referrals based on food insecurity or other nutrition concerns. Tulsa CARES also internally screens all existing clients for food insecurity during new client intake and annual reassessment appointments using a self-administered version of the 6-item Short Form Food Security Survey Module.1 Positive screenings result in a referral to the RDN or NDTR, which initiates the NCP for a more thorough assessment of client food needs.

Cejda notes that many clients living in food insecure households have other social and medical problems, such as mental health co-morbidities, substance use, diabetes, or HIV-associated wasting, all of which inform her data collection priorities during nutrition assessment. All patients receive a Nutrition-Focused Physical Exam to assess for malnutrition and lipodystrophy, including muscle mass or body fat depletion, which Cejda notes can occur as a result of HIV infection and be exacerbated by food insecurity. After completing her nutrition assessment, Cejda commonly identifies nutrition diagnoses of inadequate protein intake, excessive carbohydrate intake, and limited access to food.

Cejda’s approach to nutrition intervention typically involves a combination of food direct assistance, nutrition education, and nutrition counseling. Tulsa CARES’ on-site food pantry allows Cejda to assist clients with selecting foods that reinforce nutrition intervention goals, such as meeting protein needs or balancing macronutrient intake. The food pantry is intentionally stocked with nutrient-dense foods, such as low-sodium canned vegetables and beans, frozen fruits and vegetables, lean meats, low-fat dairy and alternatives, dried beans, and whole grain products to better meet the nutrition intervention needs of clients. Nutrition supplement assistance for individuals with identified micronutrient deficiencies or muscle wasting are also available. When working with clients affected by food insecurity, Cejda observes that, “Your nutrition intervention is often going to be simpler, and you may need to work with the client to prioritize one realistic, achievable goal at a time, as opposed to multiple goals at once. Some of my interventions and recommendations will be changed based on the degree of a client’s access to food, which can limit their readiness or ability to make dramatic eating changes compared to someone who is food secure.” For HIV-positive patients dealing with multiple diagnoses, such as diabetes, Cejda also includes interventions that set realistic goals to improve comorbidities. “[For diabetic clients], I often emphasize for patients to eat consistent meals at consistent times to prevent hypoglycemia and take their medicine on time. Education on food sources of carbohydrate and economic ways to balance these foods with lean protein and healthy fat is also essential.”

Cejda and her team monitor and evaluate clients over time for food security status and health outcome improvements, such as BMI, body composition, blood pressure, and updated lab work received through partnerships with healthcare providers. On a personal level, Cejda defines client success through subjective measures as well, such as “improved quality of life, feeling better, and less daily worry”.

Just Say Yes to Fruits and Vegetables: How Community Programs Can Apply the NCP

Public health and community dietetics practitioners are often charged with planning nutrition programs for priority populations, a process that can be guided by the NCP.27 One example is New York State’s Just Say Yes (JSY) to Fruits and Vegetables program, a Supplemental Nutrition Assisance Program (SNAP) Educational Initiative (SNAP-Ed).28 As a SNAP-Ed funded initiative, JSY is an obesity prevention program designed to promote healthy diets and active lifestyles to SNAP recipients and eligible families through the provision of behaviorally-focused nutrition education and obesity prevention strategies.28 Its initiatives include the development and adoption of policies and systems that facilitate and support environmental changes to improve healthy food access and consumption. Conversations with Paula Brewer, MS, RDN, CDN (March 2017), JSY Program Director, informed this program spotlight.

The assessment step for JSY involved collecting aggregate data.27 Brewer and her team gathered state-wide and national data from sources including the United States Department of Agriculture, Feeding America, and U.S. studies of food insecurity to identify obesity, diabetes, high blood pressure, and suboptimal dietary patterns29 as key disparities affecting the target population. Program planners then progressed to the second step of the NCP: diagnosing the community problem. They emphasized a prevention approach and prioritized goals for fruit and vegetable consumption and general healthful eating, since diets high in fruits and vegetables may help prevent obesity and hypertension30, while green, leafy vegetables are particularly helpful in the prevention of type 2 diabetes.31

According to Brewer, the intervention step included development of a two-pronged, evidence-based intervention: “Education so that people have the knowledge, the confidence, and the skill to improve their dietary intake, [and] working on the emergency food environment to increase access to healthier food.” To implement this intervention, JSY partnered with New York’s emergency food network. At partner food pantries, JSY RDNs or other trained nutrition educators deliver 45-minute, healthy eating workshops for food pantry clients. JSY partners with local food banks to help establish nutrition policies that improve the quality of food offered. Further, JSY operates a healthy pantry demonstration initiative in which pilot food pantries are strategically designed to encourage shoppers to take healthful products.

Brewer mentioned that expanding program monitoring and evaluation is a priority. Program administrators currently evaluate client intention to change behavior. Future evaluation plans include measures of fruit and vegetable intake and self-efficacy. JSY assesses their healthy pantry initiative using a process evaluation following the RE-AIM model.32

Through the implementation of general healthful eating programs and initiatives in direct collaboration with food banks, JSY illustrates how the NCP can be applied to address nutrition problems at the community level for populations affected by food insecurity.

Conclusion

At some point in their careers, dietetics practitioners working in both clinical and community settings will likely encounter individuals, groups, or populations who are at nutritional risk due to a limited food supply. Multiple action items can be implemented by these providers to support the delivery of food insecurity-informed client care (Table 3). By further considering how food insecurity may be influencing nutrition-related health outcomes and behaviors, dietetics practitioners can apply critical thinking skills along each step of the NCP. These approaches can result in a more personalized, client-centered response to improve many of the health disparities experienced by food insecure populations.

Table 3.

Action items for dietetics practitioners to support the delivery of food insecurity-informed client care

|

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Peggy Turner, MS, RDN/LD, FAND, Kim Prendergast RD, MPP, Melissa Cannon, RD, and Hilary Seligman, MD, MAS for reviewing drafts of this manuscript and providing critical comments. The authors also thank the dietitians featured in this article's program spotlights for sharing their expertise.

Funding:

Development time for this publication was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention under Award Number 3U48DP004998-01S1 and by the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number 2R25MH083635 to the American Psychological Association, Tiffany G. Townsend and Velma McBride Murry. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the CDC or the NIH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author contributions

M.S.W. conceptualized this paper and oversaw preliminary and final development of the paper in its entirety. K.C.W. conducted interviews with dietitians highlighted in the program spotlights and contributed to development of the full manuscript. C.R. contributed to the introduction, children and adolescent sections of the paper, provided expert consultation, and identified dietitian case studies for the program spotlights.

Contributor Information

Marianna S. Wetherill, Assistant Professor, University of Oklahoma College of Public Health.

Kayla Castleberry White, Research Assistant, University of Oklahoma College of Public Health.

Christine Rivera, Community Health and Nutrition Manager, Network Engagement.

References

- 1.Bickel G, Nord M, Price C, Hamilton W, Cook J. Guide to measuring household food security, Revised 2000. Alexandria VA: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coleman-Jensen A, Rabbitt MP, Gregory CA, Singh A. Household food security in the United States in 2015. United States Department of Agriculture; 2016. (Economic Research Report 215). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gunderson C, Dewey A, Crumbaugh AS, et al. Map the meal gap 2016. Chicago, IL: Feeding America; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Nutrition Terminology Reference Manual (eNCPT): Dietetics language for nutrition care. http://ncpt.webauthor.com/. Accessed August 9, 2017.

- 5.Hanson KL, Connor LM. Food insecurity and dietary quality in US adults and children: a systematic review. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;100(2):684–692. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.114.084525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tarasuk V, Mitchell A, McLaren L, McIntyre L. Chronic physical and mental health conditions among adults may increase vulnerability to household food insecurity. J Nutr. 2013;143(11):1785–1793. doi: 10.3945/jn.113.178483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seligman HK, Davis TC, Schillinger D, Wolf MS. Food insecurity is associated with hypoglycemia and poor diabetes self-management in a low-income sample with diabetes. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21(4):1227–1233. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seligman HK, Schillinger D. Hunger and socioeconomic disparities in chronic disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(1):6–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1000072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dixon LB, Winkleby MA, Radimer KL. Dietary intakes and serum nutrients differ between adults from food-insufficient and food-sufficient families: Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994. J Nutr. 2001;131(4):1232–1246. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.4.1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhattacharya J, Currie J, Haider S. Poverty, food insecurity, and nutritional outcomes in children and adults. J Health Econ. 2004;23(4):839–862. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2003.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dinour LM, Bergen D, Yeh M-C. The food insecurity–obesity paradox: A review of the literature and the role food stamps may play. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007;107(11):1952–1961. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holben D. Position of the American Dietetic Association: Food insecurity in the United States. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110(9):1368–1377. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2010.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hernandez DC, Reesor L, Murillo R. Gender disparities in the food insecurity-overweight and food insecurity-obesity paradox among low-income older adults. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2017;117(7):1087–1096. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2017.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parker ED, Widome R, Nettleton JA, Pereira MA. Food security and metabolic syndrome in US adults and adolescents: findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999–2006. Ann Epidemiol. 2010;20(5):364–370. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2010.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laraia BA. Food insecurity and chronic disease. Adv Nutr. 2013;4(2):203–212. doi: 10.3945/an.112.003277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seligman HK, Laraia BA, Kushel MB. Food insecurity is associated with chronic disease among low-income NHANES participants. J Nutr. 2010;140(2):304–310. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.112573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seligman HK, Jacobs EA, López A, Tschann J, Fernandez A. Food insecurity and glycemic control among low-income patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(2):233–238. doi: 10.2337/dc11-1627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ke J, Ford-Jones EL. Food insecurity and hunger: A review of the effects on children’s health and behaviour. Paediatr Child Health. 2015;20(2):89–91. doi: 10.1093/pch/20.2.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cook JT, Black M, Chilton M, et al. Are food insecurity’s health impacts underestimated in the US population? Marginal food security also predicts adverse health outcomes in young US children and mothers. Adv Nutr. 2013;4(1):51–61. doi: 10.3945/an.112.003228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murphy C, de Cuba SE, Cook J, Cooper R, Weill JD. Reading, writing, and hungry: The consequences of food insecurity on children, and on our nation’s economic success. Washington, DC: Partnership for America’s Economic Success; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Popkin SJ, Scott MM, Galvez M. Impossible choices: Teens and food insecurity in America. Washington, DC: The Urban Institue and Feeding America; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lacey K, Pritchett E. Nutrition Care Process and Model: ADA adopts road map to quality care and outcomes management. J Am Diet Assoc. 2003;103(8):1061–1072. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(03)00971-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O’Keefe L. AAP News. American Academy of Pediatrics; 2015. Identifying food insecurity: Two question screening tool has 97% sensitivity. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pooler J, Levin M, Hoffman V, Karva F, Lewin-Zwerdling A. Implementing food security screening for older patients in primary care: A resource guide and toolkit. AARP Foundation & IMPAQ International; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gundersen C, Engelhard EE, Crumbaugh AS, Seligman HK. Brief assessment of food insecurity accurately identifies high-risk US adults. Public Health Nutr. 2017;20(8):1367–1371. doi: 10.1017/S1368980017000180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tulsa CARES. Our story. http://www.tulsacares.org/our-story/. Accessed February 1, 2017.

- 27.Bates T, Rising C, editors. Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Public Health/Community Nutrition Nutrition Care Process (NCP) Toolkit. Chicago, IL: Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Just Say Yes to Fruits & Vegetables. About. 2017 http://jsyfruitveggies.org/about/. Accessed August 12, 2017.

- 29.Weinfield NS, Mills G, Borger C, et al. Hunger in America 2014: National report prepared for Feeding America. Westat and the Urban Institute; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boeing H, Bechthold A, Bub A, et al. Critical review: Vegetables and fruit in the prevention of chronic diseases. Eur J Nutr. 2012;51(6):637–663. doi: 10.1007/s00394-012-0380-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carter P, Gray LJ, Troughton J, Khunti K, Davies MJ. Fruit and vegetable intake and incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 2010:341. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c4229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(9):1322–1327. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]