Abstract

RORα, the RAR-related orphan nuclear receptor alpha, is essential for cerebellar development. The spontaneous mutant mouse staggerer, with an ataxic gait caused by neurodegeneration of cerebellar Purkinje cells, was discovered two decades ago to result from homozygous intragenic Rora deletions. However, RORA mutations were hitherto undocumented in humans. Through a multi-centric collaboration, we identified three copy-number variant deletions (two de novo and one dominantly inherited in three generations), one de novo disrupting duplication, and nine de novo point mutations (three truncating, one canonical splice site, and five missense mutations) involving RORA in 16 individuals from 13 families with variable neurodevelopmental delay and intellectual disability (ID)-associated autistic features, cerebellar ataxia, and epilepsy. Consistent with the human and mouse data, disruption of the D. rerio ortholog, roraa, causes significant reduction in the size of the developing cerebellum. Systematic in vivo complementation studies showed that, whereas wild-type human RORA mRNA could complement the cerebellar pathology, missense variants had two distinct pathogenic mechanisms of either haploinsufficiency or a dominant toxic effect according to their localization in the ligand-binding or DNA-binding domains, respectively. This dichotomous direction of effect is likely relevant to the phenotype in humans: individuals with loss-of-function variants leading to haploinsufficiency show ID with autistic features, while individuals with de novo dominant toxic variants present with ID, ataxia, and cerebellar atrophy. Our combined genetic and functional data highlight the complex mutational landscape at the human RORA locus and suggest that dual mutational effects likely determine phenotypic outcome.

Keywords: RORA, neurodevelopmental disorder, intellectual disability, autistic features, cerebellar ataxia, epilepsy, dual molecular effects

Introduction

Nuclear receptors appeared in the metazoan lineage as an adaptation to multicellular organization requiring distant cellular signaling through non-peptidic growth and differentiation factors.1 The nuclear receptor superfamily is a group of transcription factors regulated by small hydrophobic hormones, such as retinoic acid, thyroid hormone, and steroids.2 Mutations in nuclear receptors cause a diverse range of disorders, including central nervous system (CNS) pathologies, cancer, and metabolic disorders. For example, haploinsufficiency of RORB (MIM: 601972), encoding the nuclear receptor RORβ, results in behavioral and cognitive impairment and epilepsy,3 while biallelic mutations in RORC (MIM: 602943), encoding RORγ, result in immunodeficiency (MIM: 6166224). Nuclear Receptor Subfamily 0, Group B, Member 1 (NR0B1 [MIM: 300473]) is an orphan member of the nuclear receptor superfamily and has been implicated in sex reversal (MIM: 3000185) and congenital adrenal hypoplasia (MIM: 3002006). RORα (RORA) is most closely related to Retinoic Acid Receptor (RAR) yet functions differently; RAR acts as a ligand responsive heterodimer with retinoid X receptor (RXR). However, RORα isoforms 1 and 2 constitutively activate transcription and bind DNA as monomers at responsive elements which consist of 6-bp AT-rich sequences.7 The amino-terminal domain of the RORα1 isoform determines its affinity and specific DNA-binding properties by acting in concert with the zinc finger domain.7

RORα deficiency is known to cause the mouse staggerer (sg) phenotype, a cerebellar degenerative model.8 In humans, microdeletions overlapping RORA on 15q22.2 have been reported in affected individuals as part of a contiguous gene syndrome,9 with the smallest deletion involving two genes, NMDA receptor-regulated 2 (NARG2/ICE2) and RORA. All reported individuals with 15q22.2 microdeletion share epileptic seizures, mild intellectual disability (ID), and dysmorphic features, with variable ataxia.9 Here, we report 16 affected individuals from 13 syndromic ID-affected families with intergenic or intragenic deletions, truncating mutations, or missense changes in RORA. We modeled these genetic findings in zebrafish larvae through endogenous roraa ablation or heterologous expression of RORA, followed by relevant cerebellar phenotyping. In zebrafish models, we recapitulated the neuroanatomical features of affected humans as well as the staggerer mouse, and we show that loss of roraa leads to reduction of both the Purkinje and granule compartments of the cerebellum. Further, our in vivo data indicate that missense variants in the DNA binding domain confer a dominant toxic effect, while a missense change in the ligand binding domain results in a loss-of-function effect. Together, our data highlight how different mutation effects at the RORA locus can produce overlapping but distinct phenotypic outcomes.

Subjects and Methods

Genetic Studies and Ethics Statement

Human genetic studies conducted in research laboratories were approved by local ethics committees from participating centers (Antwerp, Belgium; Lyon, France; Frankfurt, Germany; Copenhagen, Denmark; Montpellier, France; Tartu, Estonia; Minneapolis and Kansas City, USA). Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants. All 16 affected individuals underwent extensive clinical examination by at least one expert clinical geneticist. Routine genetic testing was performed whenever clinically relevant, including copy-number variation (CNV) analysis by high-resolution array-based comparative genomic hybridization (aCGH) using (1) 180k CytoSure ISCA v2 array (Oxford Gene Technology; individuals 10A–D), (2) 180k SurePrint G3 CGH microarray as described10 (Agilent; individual 11), or (3) 400k SurePrint G3 CGH microarray, as described11 (Agilent, individuals 12 and 13). Affected individuals with a negative aCGH result underwent whole-exome sequencing (WES) on an Illumina HiSeq platform according to the following paradigms: (1) trio-based clinical diagnostic WES (individuals 1, 2, 6, 7, and 9), (2) trio-based WES in a research laboratory (individuals 3 and 4), or (3) WES of an affected individual followed by single site testing in parental DNA samples (individuals 5 and 8; see Table S1 for further details). Point mutations were confirmed by Sanger sequencing of DNA sample from all available family members, when possible.

Establishment and Culture of Primary Fibroblasts

We conducted biochemical studies in primary cultures of skin fibroblasts from individuals 2, 3, and 6 and from two control individuals (WT1 and WT2). Fibroblasts were grown in RPMI 1640 medium, containing 5% fetal calf serum (FCS, ThermoFisher, Waltham), 2 mM L-glutamine (ThermoFisher), 1% Ultroser G (Pall, Cortland), 1 × Antibiotic-Antimycotic (ThermoFisher) and were maintained in a humidified incubator at 37°C/5% CO2. Both RT-PCR and western blotting studies were performed using individual fibroblasts plated in 6-well plates (200,000 cells/well).

RT-PCR Studies in Primary Fibroblasts

Total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Plus Mini kit (QIAGEN) and reverse transcribed with the Moloney Murine Leukemia Virus Reverse Transcriptase (ThermoFisher). PCR amplification was performed with primers located in exons 3 and 4 (Table S2) and the Promega MasterMix (Promega). PCR products were separated on a 1.5% agarose gel and fragments were cut from the gel. After extraction from gel slices, the PCR products were purified with ExoSAP-IT (ThermoFisher) and sequenced by standard cycle-sequencing reactions with Big Dye terminators (ThermoFisher) with the PCR forward and reverse primers in an ABI PRISM 3130xl Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems). Mutation detection analysis was performed using 4Peaks.

RORA Immunoblotting

Total protein lysate was extracted from primary fibroblasts using 1 × Laemmli buffer. Proteins were separated on 10% SDS-PAGE gels and transferred to PVDF membrane (Westran Clear Signal Whatman; Dominique Dutscher, Brumath). The membranes were incubated overnight with 1:200 diluted anti-RORα (sc-6062, Santa Cruz biotechnology) primary antibody in 5% skim milk. Protein levels of the housekeeping protein GAPDH were assayed for internal control of protein loading with 1:1,000 diluted GAPDH antibody (sc-25778, Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

Three-Dimensional (3D) Protein Modeling

Missense changes located in the DNA-binding domain of RORA isoform a were studied by 3D modeling. Wild-type (WT) and mutated RORA DNA binding domain homology models were generated according to the crystal structure of the RXR-RAR DNA-binding complex on the retinoic acid response element DR1 using Modeler12 software with standard parameters.

RORA Expression Analysis in Neuronal Cell Types

There are four RefSeq transcripts of RORA (GenBank): NM_134261.2 (RORA 1), NM_134260.2 (RORA 2), NM_002943.3 (RORA 3), and NM_134262.2 (RORA 4). Relative mRNA levels of the four RORA transcripts were assessed in three different commercially obtained human cDNAs by quantitative (q)RT-PCR: (1) cerebellar cDNA from a 26-year-old male (Amsbio), (2) whole-brain cDNA pooled from two males of Northern European descent aged 43–55 years, Human multiple tissue cDNA (MTC) panel I (Clontech), and (3) Human Universal QUICK-Clone II (Clontech) using transcript-specific primers (Table S2) and SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Thermo Fisher) on an ABI 7900HT real-time PCR system. We determined relative gene expression levels in quadruplicate samples according to the ΔCt method. After normalization to β-actin levels, −log2 of ΔCt for each of the four transcripts was added together to determine total expression levels from the RORA locus for each cDNA. Relative RORA transcript expression levels expressed in −log2 of ΔCt were obtained by calculating the percentage of each transcript compared to total RORA expression.

Zebrafish Lines and Husbandry

All zebrafish work was performed in accordance with protocols approved by the Duke University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Zebrafish embryos were obtained by natural matings of WT (ZDR strain, Aquatica BioTech) or transgenic (neurod:egfp) adults13 and maintained on a 14 hr/10 hr light-dark cycle. Embryos were reared in embryo media (0.3 g/L NaCl, 75 mg/L CaSO4, 37.5 mg/L NaHC03, 0.003% methylene blue) at 28°C until processing for phenotypic analyses at 3 days post-fertilization (dpf).

CRISPR/Cas9 Genome Editing of roraa in Zebrafish

We designed two guide (g) RNAs targeting roraa (GRCz10: ENSDARG00000031768) using the CHOPCHOP v2 tool14 and synthesized them in vitro with the GeneArt precision gRNA synthesis kit (Table S2; Thermo Fisher) as described.15, 16, 17 We targeted the roraa locus by microinjection into the cell of zebrafish embryos with 1 nL of cocktail containing 100 pg gRNA and 200 pg Cas9 protein (PNA Bio) at the 1-cell stage. We harvested individual embryos (n = 8) at 1 dpf for DNA extraction to assess targeting efficiency. We PCR-amplified the region flanking the targeted site (Table S2), denatured the resulting product, and reannealed it slowly to form heteroduplexes (95°C for 5 min, ramped down to 85°C at 1°C/s and then to 25°C at 0.1°C/s). We performed polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) on a 20% precast 1 mm gel (Thermo Fisher) to visualize heteroduplexes. To estimate mosaicism of F0 mutants, PCR products were cloned into a TOPO-TA vector (Thermo Fisher) and individual colonies (n = 24) were sequenced (n = 3 larvae/gRNA).

Transient roraa Suppression, In Vivo Complementation, and Heterologous Expression Experiments

We designed splice blocking (sb) morpholinos (MO) targeting either the splice donor site of exon 2 (e2i2) or exon 3 (e3i3) of roraa (GeneTools, LLC; Table S2) and injected 1 nL of MO into the yolk of zebrafish embryos at 1- to 4-cell stage. To confirm expression of the two annotated roraa transcripts (GRCz10: ENSDART00000148537.2 and ENSDART00000121449.2) and to determine MO efficiency, we harvested uninjected control and MO-injected larvae in Trizol (Thermo Fisher) at 3 dpf, extracted total RNA, and conducted first-strand cDNA synthesis with the QuantiTect Reverse Transcription kit (QIAGEN). The targeted region of roraa was PCR amplified using primers complementary to sites in flanking exons (Table S2) and migrated by electrophoresis on a 1% agarose gel; bands were excised, gel purified using QIAquick gel extraction kit (QIAGEN) and resulting clones were Sanger sequenced. The optimal MO dose for in vivo complementation experiments was determined by injection of three concentrations of MO (2, 3, 4 ng of e2i2; or 6, 7, 8 ng of e3i3). To generate mRNA for injections, we purchased Gateway-compatible open reading frame (ORF) clones from Genecopoeia (RORA 1, RORA 2, and RORA 3) or Thermo Fisher (RORA 4) and transferred the ORFs to a pCS2+ vector by LR clonase II-mediated recombination (Thermo Fisher). We performed site-directed mutagenesis of RORA 4 according to the QuikChange protocol (Table S2; Agilent), using described methodology;18 sequences were validated by Sanger sequencing. Linearized pCS2+ vectors containing WT or mutant ORFs were transcribed in vitro with the mMessage mMachine SP6 Transcription kit (Ambion).

Whole-Mount Immunostaining

We stained axonal tracts of the cerebellum with monoclonal anti-acetylated tubulin antibody produced in mouse (Sigma-Aldrich, T7451, 1:1,000), as described.19 We fixed larvae in Dent’s solution (80% methanol and 20% DMSO) and carried out primary antibody detection overnight and secondary detection for 1 hr with Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-mouse IgG (A11001, Invitrogen; 1:1,000). We visualized the Purkinje compartment of the zebrafish cerebellum with anti-zebrin II antibody (a gift from Dr. Richard Hawkes) in neurod:egfp transgenic larvae. Briefly, zebrafish larvae were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and incubated overnight in mouse anti-zebrin II antibody (1:100); secondary antibody was applied for 1 hr (Alexa Fluor 594 goat anti-mouse IgG, A11005, Invitrogen; 1:1,000). Fluorescent signal was imaged manually on dorsally positioned larvae using an AxioZoom.V16 microscope and Axiocam 503 monochromatic camera, using Zen Pro 2012 software (Zeiss). Cerebellar structures of interest or optic tecta were measured using ImageJ.20 Total cerebellar area was measured on acetylated tubulin-stained larvae by outlining structures with fluorescent signal; regions comprised of Purkinje cells were measured on zebrin II-stained regions; region comprised of granule cells were measured on GFP-positive regions. Statistical analyses were performed using a two-tailed parametric t test (GraphPad software).

Results

Identification of Point Mutations or Copy-Number Variants Disrupting RORA

As part of our ongoing studies to understand the molecular basis of neurodevelopmental disorders, we identified a total of 16 individuals with rare variants suspected to alter RORA function (Figure 1; Tables 1, S3, and S4). The first individual under investigation was a female with severe syndromic ID, multifocal seizures, mild cerebellar hypoplasia, and hypotonia (individual 6, Table 1; Figure 2A). Upon performing WES, we identified a de novo frameshifting mutation in RORA (GenBank: NM_134261.2; c.1019delG [p.Arg340Profs∗17]) that was not present in the genome aggregation database (gnomAD; >246,000 chromosomes) or the NHLBI Exome Variant Server (EVS; >13,000 alleles). Information exchange on community data-sharing platforms including GeneMatcher,21 the DatabasE of genomiC varIation and Phenotype in Humans using Ensembl Resources (DECIPHER), and the Broad Institute matchbox repository facilitated the identification of an additional 15 affected individuals with RORA variants who displayed overlapping phenotypes. These variants were present de novo in 11 simplex families with affected individuals and segregated in one three-generation pedigree under a dominant paradigm, bolstering the candidacy of this locus. Of note, segregation analysis was impossible in individual 1’s family, since the child had been adopted.

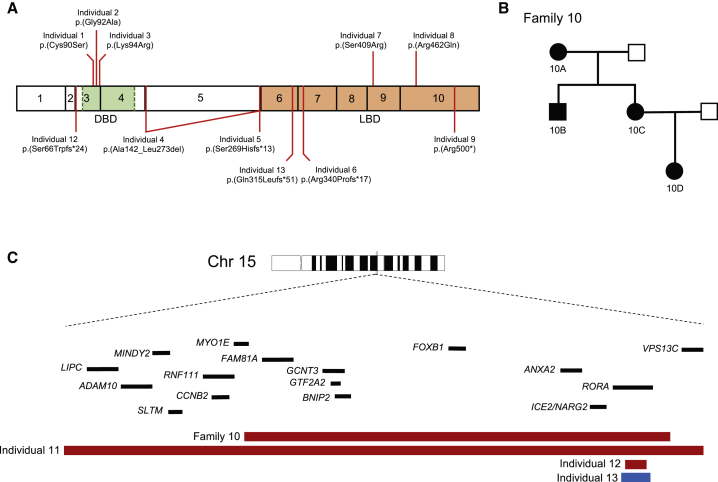

Figure 1.

RORA Variants Cause Intellectual Disability with Autistic Features or Cerebellar Hypoplasia

(A) Schematic of RORα isoform a (GenBank: NP_599023.1; encoded by RORA transcript 1) depicting exons (black outlined boxes with numbers 1–10) and domains; green, DNA binding domain (DBD); orange, ligand binding domain (LBD). Missense variants (top) and truncating variants (bottom) are shown.

(B) Autosomal-dominant pedigree (family 10) in which a ∼1.5 Mb intergenic deletion containing RORA segregates with disease. Filled shapes, affected individuals; unfilled shapes, healthy individuals. Individuals 10A, 10B, 10C, 10D, and the spouse of 10C were tested.

(C) Schematic depicting the RORA locus at 15q22. Zoomed region shows two intergenic deletions (individuals 10A–D and individual 11), one intragenic deletion (individual 12), and an intragenic duplication (individual 13) involving RORA. Genes are indicated by black bars; copy number loss, red; copy number gain, blue.

Table 1.

Molecular and Clinical Data from the 15 Individuals with RORA Variants

|

Individual ID |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10D |

10C |

10B |

10A |

11 |

12 |

13 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DECIPHER ID | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 289628 | – | 255754 | 293939 |

| Sex | female | male | female | female | female | female | male | male | male | female | female | male | female | male | male | male |

| Geographic origin | USA | Estonia | France | USA | USA | France | USA | Germany | USA | Belgium | Belgium | Belgium | Belgium | France | Denmark | Denmark |

| Age at last investigation (years) | 4 | 3.5 | 6 | 28 | 3 | 10 | 9 | 4 | 14 | 25 | 50 | 44 | 80 | 15 | 8 | 6,5 |

| Mutation type | missense | missense | missense | splice site | frameshift | frameshift | missense | missense | nonsense | 15q22 deletion including RORA | 15q22 deletion including RORA | 15q22 deletion including RORA | 15q22 deletion including RORA | 15q22.3q22.2 deletion including RORA | 15q22 intragenic deletion of RORA | 15q22 disruptive duplication of RORA |

| Mutation (GRCh37)a | c.269G>C | c.275G>C | c.281A>G | c.425-1G>A | c.804_805delGT | c.1019delG | c.1225A>C | c.1385G>A | c.1498C>T | 15q22.2 (59,641,986-61,104,231) x1 | 15q22.2 (59,641,986-61,104,231) x1 | 15q22.2 (59,641,986-61,104,231) x1 | 15q22.2 (59,641,986-61,104,231) x1 | 15q21.3q22.2 (58,622,268 −62,320,616) x1 | 15q22.2 (60,809,984-60,837,029) x1 | 15q22.2 (60,797,691-60,860,668) x3 |

| Protein variantb | p.Cys90Ser | p.Gly92Ala | p.Lys94Arg | p.Ala142_Leu273del | p.Ser269Hisfs∗13 | p.Arg340Profs∗17 | p.Ser409Arg | p.Arg462Gln | p.Arg500∗ | – | – | – | – | – | p.Ser66Trpfs∗24 | p.Gln315Leufs∗51 |

| Mode of inheritance | unknown (adopted) | de novo | de novo | de novo (mosaic, 20% in blood) c | de novo | de novo | de novo | de novo | de novo | dominant; inherited from mother (ID 10C) | dominant; inherited from mother (ID 10A) | dominant; inherited from mother (ID 10A) | dominant | de novo | de novo | de novo |

| Functional effectd | NA | dominant toxic | dominant toxic | NA | NA | NA | NA | loss-of-function | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Growth Parameters | ||||||||||||||||

| Birth weight (grams/SD) | NA | 3,500/0 | 3,310/0 | 4,238/+2 | 4,054/+1.4 | 2,655/−1.5 | 3,487/0 | NA | 3,340/−0.4 | NC/+0.7 | NA | NA | NA | 3,200/−0.5 | 4050/+1 | NC; unremarkable |

| Birth length (cm/SD) | NA | 52/+1 | 49/0 | NA | 54.6/+1.9 | 46/−2 | 52/+1 | NA | 48.3/−0.7 | NC/+0.7 | NA | NA | NA | 49.5/0 | 56/+2.5 | NC; unremarkable |

| Birth head circumference (cm/SD) | NA | 38/+2.5 | 34.5/0 | NA | NA | 33/−1 | 34/−0.5 | NA | 46.5/+2 (6 mo) | NC/+0.7 | NA | NA | NA | 34/−0.5 | NA | NC; unremarkable |

| Height at age last investigation (cm/SD) | 102/0 | 102/+0.5 | 104/−2 | 167.8/+0.5 | 89/−1.5 | 132/−1 | 120.8/−2 (8 y 5 mo) | NA | 150.4/−0.7 (13 y) | 166/+0.7 | NA | NA | NA | 170/0 | NC/+2.5 | NC/−1 |

| Weight at age last investigation (kg/SD) | 17.2/+0.5 | 17.8/+1 | 16/−1.5 | 69.4/+1 | 14.5/+0.3 | 26.2/−1.3 | 31/+1.3 (9 y 3 mo) | NA | 44.4/−0.2 (13 y) | 74.3/+1.3 | NA | NA | NA | 58/+0.7 | NC/+1 | NC/−1 |

| Head circumference at age last investigation (cm/SD) | 49/0 | 50.6/0 | 50/0 | 58.4/+1.9 | NA | 53/0 | 51.7/−0.3 (8 y 4 mo) | NA | 58/+2.6 (13 y) | 54/−0.7 | NA | NA | NA | 56/+0.7 | NA | NA |

| Degree of developmental delay or ID | mild | mild-moderate | severe | mild (regression at 10 years) | mild | severe | mild | no ID (IQ 85) | moderate | mild | mild | mild | mild | moderate | mild | mild |

| Age of walking | 2 years | 3 years | 6 years | 14 months | 20 months | 3 years | 15 months | NA | 24 months | 16 months | NA | NA | NA | 21 months | normal | mild delay |

| Age of first words | 2 years | delayed | before 1 year | 14–15 months | 12–13 months | 5 years | >2 years | NA | delayed | 14 months | NA | NA | NA | 2 years | delayed | delayed |

| Current language ability | speaking with sentences | speaking with sentences | no phrase | normal | around 20 words | no phrase | delayed | normal | rudimentary sentences | delayed | NA | NA | NA | normal | delayed | delayed |

| Behavioral anomalies | no | no | no | no | ASD | ASD | ASD | ASD | no | behavioral problems | no | borderline personality disorder | no | hyperactivity | no | ASD |

| Neurological Examination | ||||||||||||||||

| Seizures (age at onset/type) | no | no | yes (4 years/absences) | yes (8 years/tonic-clonic seizures) | yes (ND/1 episode of absence) | yes (5 years/multifocal) | yes (neonatal/myoclonic seizures) | no | yes (ND/generalized seizures) | yes (4 years/absences, drop attacks) | yes | yes (ND/generalized, status epilepticus) | no | yes (ND/generalized, febrile seizures) | no | yes |

| Neurological examination | tremor, hypotonia, coordination disorder | tremor, hypotonia, ataxia | tremor, hypotonia, ataxia, pyramidal syndrome | tremor, hypotonia, ataxia | hypotonia, poor coordination | tremor, hypotonia, ataxia | occasional fine tremor | NA | mild hand tremor, hypotonia | NA | NA | tremor | no | palpebral myoclonia | no | no |

| Brain imaging | normal | cerebellar hypoplasia (mainly vermis) | pontocerebellar atrophy (mainly vermis) | NA | normal | mild global cerebellar hypoplasia | corpus callosal hypoplasia | NA | CSF spaces mildly prominent | normal | NA | normal | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Global Examination | ||||||||||||||||

| Eye anomalies | strabismus, esotropia, nystagmus, amblyopia | no | mild oculomotor apraxia, strabismus | visual processing deficits | no | no | esotropia, hyperopia | NA | strabismus, hyperopia | strabismus | strabismus | NA | NA | strabismus | no | no |

| Other | – | spina bifida occulta | recurrent vomiting, constipation | hypoglycemia in childhood | bilateral hydronephrosis | hypercholesterolemia | popliteal contractures | – | cryptorchidism, renal cysts | – | – | – | – | – | atopic dermatitis | – |

| Other genetic findings | VUS in NR4A2 | – | maternally inherited heterozygous p.(Arg662∗) in DNM1L | – | maternally inherited deletions of 3p26.3 and 10q21.3 (both classified as VUS), mother reports no history of developmental delays | – | HSPG2 c.7006+1G>A (maternally inherited), HSPG2 c.4391G>A (paternally inherited), GSK3B c.625dupC (de novo), CACNA1A c.5883G>A (maternally inherited) | – | NGLY1 c.1516C>T, p.Arg506∗ (maternally inherited), PKD2 c.2143delC, (p.Leu715∗) (paternally inherited), 3p26.2 deletion (maternally inherited; VUS) | intragenic DISC1 deletion (1q42.2(231,834,554–231,885,282)x1 | intragenic DISC1 deletion (1q42.2(231,834,554–231,885,282)x1 | intragenic DISC1 deletion (1q42.2(231,834,554–231,885,282)x1 | intragenic DISC1 deletion (1q42.2(231,834,554–231,885,282)x1 | – | – | – |

| Initial diagnostic hypotheses | none | ID and disorders with cerebellar involvement | congenital ataxia with pontocerebellar atrophy | disorder of mitochondrial metabolism | none | none | speech delay, toe walking | idiopathic ASD F84.0 | CUL4B-related disorder | GGE and ID | ID and possible epilepsy | ID? | epilepsy (GGE?) and ID | deletion of RORB | none | none |

Abbreviations: LoF, loss of function; GoF, gain of function; ND, not determined; ASD, autism spectrum disorder; ID, intellectual disability; IQ, intelligence quotient; GGE, genetic generalized epilepsy; NA, not analyzed; NC, not communicated; ND, not determined; y, years.

Nomenclature HGVS V2.0 according to mRNA reference sequence GenBank: NM_134261.2. Nucleotide numbering uses +1 as the A of the ATG translation initiation codon in the reference sequence, with the initiation codon as codon 1.

Inferred from bioinformatic predictions but not verified from the individual’s mRNA.

Mosaicism was inferred and estimated initially from raw exome sequencing data and confirmed by Sanger sequencing.

Effect inferred from in vivo tests in zebrafish or analyses from patient fibroblasts; in vitro experiments.

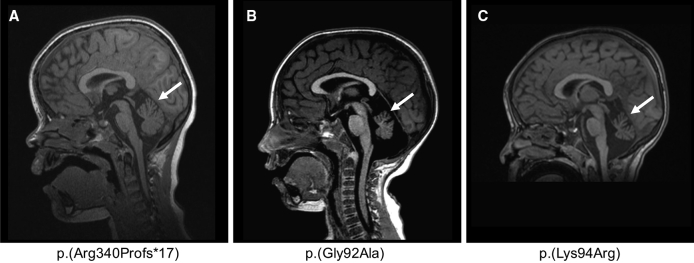

Figure 2.

Brain MRI of Individuals with Cerebellar Hypoplasia

MRI of individual 6 done at 6.5 years old (A), individual 2 done at 2 years and 1 month old (B), and individual 3 done at 2 years old (C) showing cerebellar hypoplasia, predominant on the vermis (white arrow). T1-weighted sequence, sagittal section through cerebellum.

Of the 16 affected individuals, 4 harbored likely pathogenic SNVs predicted to alter RORA protein sequence or dose. In addition to individual 6, three affected individuals had de novo SNVs or small indels in RORA; these included one frameshifting mutation, one nonsense mutation, and one mosaic canonical splice acceptor site change (Figure 1A; Tables 1 and S3). These three RORA variants are predicted to result in protein sequence with either complete (c.804_805delGT [p.Ser269Hisfs∗13]) or partial (c.1019delG [p.Arg340Profs∗17] and c.1498C>T [p.Arg500∗]) truncation of the ligand binding domain at the C terminus and/or nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (NMD). Notably, analyses of fibroblast protein lysates from individual 6 (p.Arg340Profs∗17) showed that RORA protein levels were not decreased compared to control subjects, suggesting that related mRNA harboring the premature stop codon would not be eliminated by NMD. According to Alamut software (compiling five different prediction tools: Splicesite Finder-like, MaxEntScan, NNSPLICE, GeneSplicer, and Human Splicing Finder), the splice acceptor site mutation, c.425−1G>A, is predicted to cause in-frame exon skipping and deletion of 77 amino acids (p.Ala142_Leu273del); however, cell lines were unavailable from the affected individual to confirm this prediction; mosaicism was estimated at about 20% from exome and Sanger sequencing data.

An additional seven affected individuals had non-recurrent CNVs impacting the RORA locus detected by high-resolution aCGH (Tables 1 and S4; Figures 1A–1C and S1). We identified one ∼63 kb duplication interrupting RORA exons 3–6, which is predicted to result in a premature termination of the protein (p.Gln315Leufs∗51), one intragenic CNV that resulted in a ∼27 kb deletion of RORA exon 3 and its flanking intronic regions to produce a putative frameshifting truncation, and one ∼3.7 Mb intergenic deletion impacting 17 genes on 15q22.3q22.2 including RORA. Segregation in each of the three families showed that all three CNVs occurred de novo. Furthermore, we detected a ∼1.5 Mb intergenic deletion in four individuals segregating neurological phenotypes in an autosomal-dominant pedigree (Figure 1B); this CNV encompasses nine genes, including RORA.

Finally, an additional five affected individuals had missense mutations predicted to be deleterious (Tables 1 and S3; Figure S2). All five alleles were absent from all available public databases queried (gnomAD, ExAC, EVS). Two of the five variants, c.1225A>C (p.Ser409Arg) and c.1385G>A (p.Arg462Gln), map to the ligand binding domain; both residues are conserved in vertebrate orthologs of RORα but not in the human paralogous nuclear receptor proteins, indicating that these positions are specific to the ROR sub-family. The other three variants—c.269C>G (p.Cys90Ser), c.275G>C (p.Gly92Ala), and c.281A>G (p.Lys94Arg)—are located in the conserved zinc-finger DNA-binding domain of RORα. The three residues Cys90, Gly92, and Lys94, together with Cys93, belong to the P box motif that is part of the alpha-helix of the first zinc-finger domain of the nuclear receptors and interacts directly with DNA (Figure S3A).22 Because the c.281A>G variant lies in the donor splice site of exon 3, we examined whether it impacts mRNA splicing in primary skin fibroblasts from individual 3; RT-PCR showed neither abnormal sized product nor semiquantitative differences in cDNA amounts (Figures S4A and S4B). Additionally, western blotting of lysates from primary fibroblasts harboring the c.275G>C change (individual 2) showed a modest increase of RORα levels when compared to a matched control (Figure S4C).

Clinical Features of Individuals with RORA Variants

The 16 affected individuals in our cohort display complex phenotypes with regards to their cognition, motor function, and electrophysiology (Table 1). The predominant phenotype was ID. However, cognitive function was variable among the 16 individuals and ranged from mild to moderate (13/16) to severe (2/16), while one individual had a low intelligence quotient (IQ) without ID. We noted IQ regression in one affected individual (individual 4) who had cognitive decline at ∼10 years of age. Developmental milestones were also delayed. The mean age of walking was delayed in 8/12 individuals; 11/12 walked by 3 years of age. Further, 11/13 individuals had speech delay and/or poor verbal communication abilities, and 2 were not speaking in sentences by the age of 6. We diagnosed epilepsy in 11/16 individuals (Table 1); the predominant seizure semiology was that of a generalized epilepsy with absences, drop attacks, and tonic-clonic seizure sub-types. None of the patients with RORA intragenic mutation had overt dysmorphic facial features. Of the nine individuals who underwent brain MRI, six had normal results and three were diagnosed with cerebellar hypoplasia, which predominantly affected the vermis (individuals 2 and 3; Figures 2B and 2C). These individuals developed early-onset ataxia and hypotonia by age 1.

Modeling RORA Disruption in Zebrafish

To corroborate the Rorasg mouse mutant phenotype data8, 23 and to determine the effect of missense variants identified in affected individuals, we developed zebrafish models of RORA ablation and expression. We and others have shown previously that zebrafish is a robust model of neuroanatomical phenotypes observed in humans.19, 24, 25, 26 In particular, assay of cerebellar defects in zebrafish has provided crucial insights toward understanding underlying pathomechanism,27, 28, 29 especially given the high conservation of granule and Purkinje cell types between mammals and teleost species.30 First, we aimed to model RORA disruption in vivo by targeting and knocking down the relevant zebrafish ortholog. Through reciprocal BLAST of the zebrafish genome and four annotated human RORA transcripts (GenBank: NM_134261, NM_134260, NM_002943, and NM_134262; Figure S5A), we identified two zebrafish orthologs: roraa (Ensembl ID: ENSDARG00000031768; GRCz10; 88%, 91%, 91%, and 91% identity to proteins encoded by RORA 1, RORA 2, RORA 3, RORA 4, respectively) and rorab (Ensembl ID: ENSDARG00000001910; 69%, 72%, 72%, and 73% identity to RORA 1, RORA 2, RORA 3, RORA 4, respectively). Next, we considered endogenous expression data to determine the most appropriate D. rerio transcript(s) to modulate in vivo. RNA in situ hybridization studies in zebrafish larvae have documented roraa expression patterns in the developing cerebellum as well as other anterior structures (optic tecta, hindbrain, and retina). However, rorab expression is restricted to the hindbrain.31, 32 Considering both the amino acid conservation and also the spatiotemporal expression of roraa in the developing cerebellum, we deemed roraa as the most relevant D. rerio locus to test the activity of RORA mutations in humans.

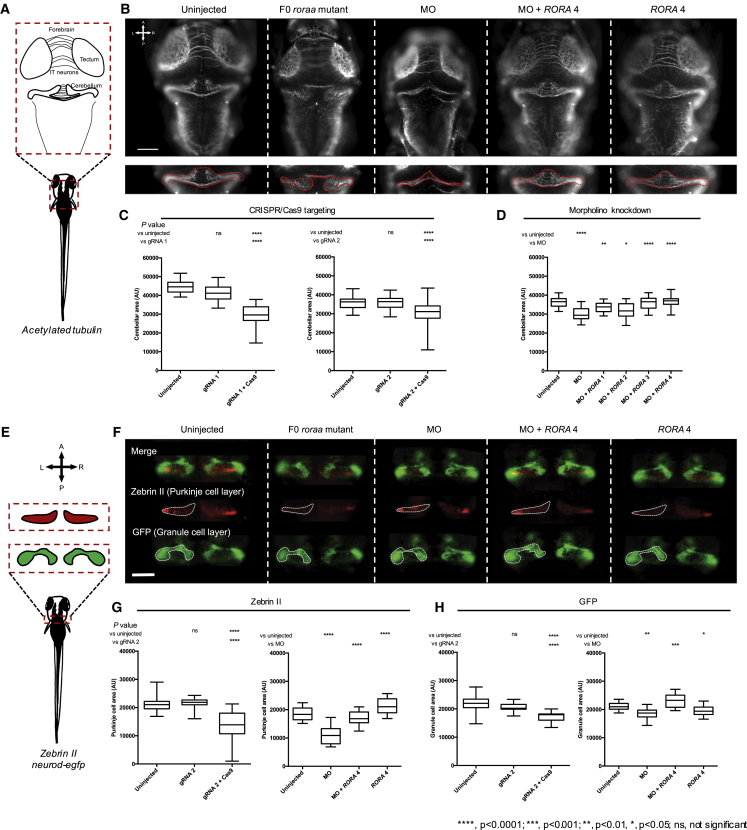

Haploinsufficiency or knockout of Rora in mice lead to abnormal cerebellar layer morphology.8, 23 Therefore, to assess the effect of loss of RORA function consistent with deletion or truncating mutations identified in affected individuals, we compared the size of the developing cerebellum between roraa knock-down and uninjected controls. The zebrafish roraa locus has two annotated transcripts (GRCz10: [roraa-201] ENSDART00000121449.2 and [roraa-202] ENSDART00000148537.2), the latter of which has an incomplete 5′ coding sequence; RT-PCR using cDNA originating from 3 dpf embryos confirmed that both transcripts are detectable in this time window (Figures S6A and S6B). Next, we generated CRISPR/Cas9-based zebrafish F0 mutant models by targeting exon 5 or exon 8 of roraa-201 (corresponding to exon 4 or exon 7 of roraa-202) to produce mosaic mutants with >90% mosaicism (Figure S7). Immunostaining of the central nervous system (CNS) with anti-acetylated tubulin antibody and measurements of neuroanatomical structures showed that roraa F0 mutants display a reduced cerebellar area and smaller optic tecta area compared to either control larvae or larvae injected with gRNA alone (p < 0.0001, for gRNA 1 and gRNA 2, n = 33–43 and 41–45 larvae/batch, respectively, repeated, masked scoring; Figures 3A–3C and S8A–S8C).

Figure 3.

Disruption of roraa in Zebrafish Larvae Results in Cerebellar Hypoplasia Driven by Purkinje and Granule Cell Loss

(A) Schematic of neuroanatomical structures painted with anti-acetylated tubulin antibody at 3 days post fertilization (dpf); IT, intertectal.

(B) Representative dorsal images of acetylated tubulin immunostained larvae show that roraa ablation causes cerebellar defects in CRISPR/Cas9 F0 mutants and morphants. Cerebellar size was measured as indicated by the dashed red outline on inset panels.

(C) Quantification of cerebellar area in larval batches is shown for two guide (g)RNAs targeting either roraa exon 5 (gRNA 1) or exon 8 (gRNA 2).

(D) roraa morphants (injected with 3 ng morpholino; MO) display a cerebellar phenotype that can be rescued by four different wild-type RORA mRNA transcripts: co-injection of roraa e2i2 splice-blocking MO with RORA splice variants (RORA 1, GenBank: NM_134261, RORA 2: NM_134260, RORA 3: NM_002943 and RORA 4: NM_134262).

(E) Schematic of cerebellar cell types assessed in 3 dpf larvae using either a neurod:egfp transgene (green) or anti-zebrin II immunostaining (red). Orientation is indicated with A, anterior; P, posterior; L, left; R, right.

(F) Representative dorsal images show that reduction of Purkinje and granule cells contributes to cerebellar defects induced by roraa targeting. Transgenic neurod:egfp larvae were fixed and immunostained with anti-zebrin II antibody (red), and the area comprised of each cell type was measured (as indicated in the schematic). Dashed white lines indicate measured area.

(G) Quantification of granule layer cells (GFP-positive).

(H) Quantification of Purkinje cells (zebrin II-positive). Both cell populations are reduced significantly in roraa F0 mutants as well as morphant zebrafish.

Scale bar in (B) and (F): 100 μm. AU, arbitrary units. Stars indicate p value compared to uninjected controls (CRISPR/Cas9 and MO) or to morphants (MO + RORA). ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗p < 0.05; ns, not significant. Error bars in (C), (D), (G), and (H) represent the 5th and 95th percentiles.

To assess phenotype specificity and to determine the effect of RORA missense variants, we performed MO-mediated transient suppression of roraa. We designed two sb MOs targeting the splice donor site of exons 2 and 3 of roraa-201, which we injected into embryo batches, generated cDNA at 3 dpf, and performed RT-PCR to determine efficiency; subsequent Sanger sequencing confirmed a frameshifting deletion of roraa exon 2 or exon 3 (Figures S6C and S6D). Next, we injected increasing concentrations of either MO (2, 3, 4 ng e2i2; or 6, 7, 8 ng e3i3). Consistent with our CRISPR F0 mutant data, we observed a dose-dependent reduction in cerebellar size for both reagents (p < 0.0001, 30 to 94 larvae/condition, Figure S6E). Co-injection of e2i2 sb MO with each of the four RefSeq annotated WT human RORA mRNAs rescued cerebellar and optic tecta defects, indicating MO specificity (p = 0.0060, 0.0387, < 0.0001, < 0.0001 for RORA 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively, versus MO, n = 31–60 larvae/batch, repeated, Figures 3B, 3D, S8A, and S8D). In parallel, heterologous expression of each of the four WT RORA mRNAs did not lead to cerebellar phenotypes that differed from uninjected controls (n = 40–52 larvae/batch, Figure S9). To investigate further the relative expression of the four annotated RORA transcripts and to identify the most relevant isoform for in vivo modeling in zebrafish, we performed qRT-PCR on commercial human adult cDNA; we identified RORA 4 as the most abundantly expressed transcript in the human CNS (Figures S5A and S5B), potentially explaining the observation that WT RORA 4 mRNA produced the most significant restoration of cerebellar size when co-injected with MO.

Altered Purkinje and Granule Layers in roraa Zebrafish Models

Similar to mammals, Purkinje and granule cell crosstalk is vital for the function of the zebrafish cerebellum.30 Cerebellar cell subpopulations have been characterized previously in zebrafish with lineage-specific markers and transgenic lines. In neurod:egfp transgenic zebrafish, granule cells are marked with GFP.29 Furthermore, zebrin II is a specific marker of the Purkinje compartment,27 which develops between 2.3 and 4 dpf.33 To assess whether roraa suppression affects granule or Purkinje cell layers of zebrafish cerebellum, we conducted whole-mount zebrin II immunostaining on neurod:egfp transgenic zebrafish larvae at 3 dpf. F0 roraa mutants presented with a significantly decreased size of Purkinje and granule cell layers compared to controls (p < 0.0001 for both cell types; Purkinje cells, n = 26–55; granule cells, n = 11–55, repeated; Figures 3E–3H and S10A–S10C). Importantly, gRNA injected alone was indistinguishable from controls (Figures 3G and 3H). Injection of e2i2 MO recapitulated these observations (p < 0.0001 or p < 0.001 for Purkinje [n = 29–55] and granule [n = 30–55] cells, respectively, in morphants versus controls; repeated; Figures 3E–3H and S10). Further, co-injection of e2i2 MO with WT human RORA 4 mRNA rescued the measured area of each of the granule and Purkinje compartments (p < 0.0001 or p < 0.001 versus MO alone for Purkinje or granule cells, respectively; Figures 3E–3H and S10). Together, our data confirm that in F0 mutant or transient knockdown zebrafish models, roraa disruption leads to defects of Purkinje and granule cell layers, consistent with the Rorasg mouse model.34, 35, 36

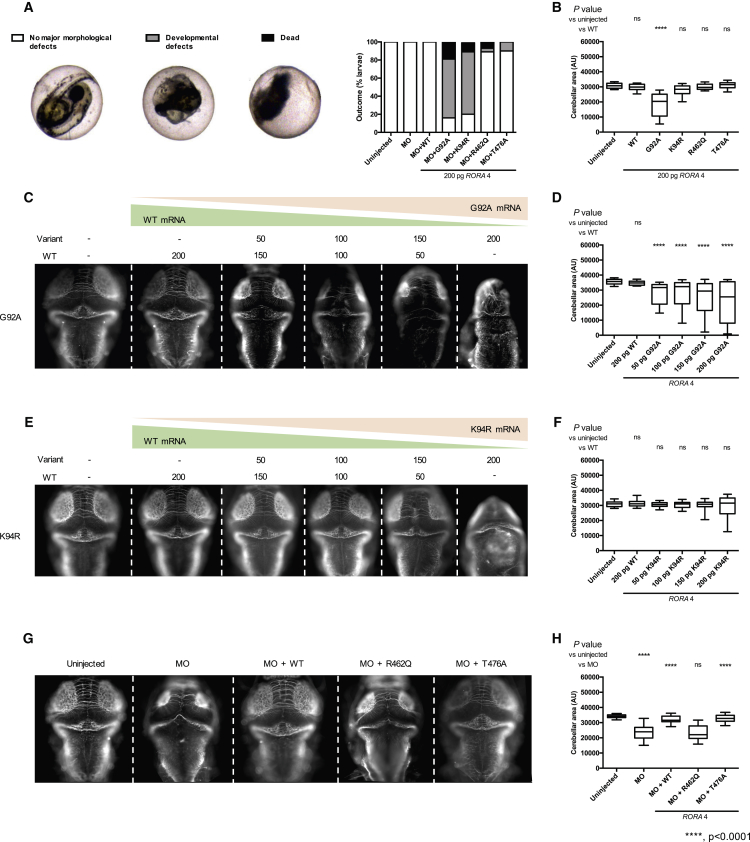

In Vivo Complementation Studies Indicate Dual Direction of RORA Allele Effect

To determine the pathogenicity of RORA missense variants (c.275G>C [p.Gly92Ala], c.281A>G [p.Lys94Arg], and c.1385G>A [p.Arg462Gln]), we assessed the effect of mutant RORA 4 mRNA in the presence or absence of MO. First, we tested a loss-of-function hypothesis by co-injecting roraa e2i2 MO with WT or variant RORA 4 mRNA. In vivo complementation of roraa MO with p.Gly92Ala or p.Lys94Arg encoding mRNA resulted in early developmental defects including a reduction in the size of anterior structures and tail extension failure (65% and 69%, respectively) and a high mortality rate (19% and 10%, respectively), while co-injection of MO with p.Arg462Gln, WT, or a potentially benign variant p.Thr476Ala (rs190933482, minor allele frequency 0.001 in gnomAD) induced no appreciable morphological defects (Figure 4A). The gross morphological phenotype observed by co-injection of MO with mutant mRNAs located in the DNA binding domain was more severe than the morphant phenotype and suggested either a dominant-negative or a gain-of-function effect. To investigate these possibilities, we injected 200 pg of each mutant mRNA alone and again observed notable mortality at 3 dpf (2% for controls [1 dead larva/54] versus 31% for p.Gly92Ala [14/45]; 9% for p.Lys94Arg [4/46]; and 7% for p.Arg462Gln [3/41]). Of the larvae that survived to 3 dpf, we performed anti-acetylated immunostaining and measurement of the cerebellar area; p.Gly92Ala encoding mRNA induced a reduction in the mean cerebellar area compared to WT (p < 0.0001, 31–53 larvae/batch, Figure 4B). To determine whether WT mRNA could rescue the phenotypes induced by p.Gly92Ala, we titrated increasing amounts of p.Gly92Ala mRNA together with RORA 4 WT mRNA and observed a dose-dependent effect that correlated with the injected dose of p.Gly92Ala (Figures 4C and 4D). These data suggested a dominant toxic effect as the likely mechanism for the p.Gly92Ala variant. Although expression of p.Lys94Arg induced morphological defects similar to p.Gly92Ala and we observed a broadened distribution of cerebellar measurements at the highest dose of mutant mRNA that was consistent with p.Gly92Ala, these results did not reach statistical significance (Figures 4E and 4F). Finally, in vivo complementation of roraa MO with p.Arg462Gln encoding mRNA did not rescue the size of the cerebellum (Figures 4G and 4H, p < 0.001, n = 40–41), suggesting a loss-of-function effect as the possible disease mechanism for this change impacting the ligand binding domain (Figures 4G and 4H).

Figure 4.

RORA Missense Variant Located in the DNA Binding Domain and Ligand Binding Domain Confer a Dominant Toxic and Loss-of-Function Effect, Respectively

(A) Complementation of roraa morpholino (MO) with variant mRNA results in severe gross morphological defects or larval death before 3 days post-fertilization (dpf). Left, representative embryo classes are shown; right, quantification of outcomes. p.Gly92Ala (G92A), p.Lys94Arg (K94R) are located in the DNA binding domain; p.Arg462Gln (R462Q) localizes to the ligand-binding domain; T476A (rs190933482) is a negative control for the assay with an allele frequency of 0.001091 in gnomAD).

(B) Quantification of cerebellar area of larval batches with ectopic expression of RORA mRNA. G92A mRNA confers a significant reduction in cerebellar size.

(C) Representative dorsal images of 3 dpf larvae injected with gradually modified doses of WT and G92A RNA (top, amount in pg) and stained with anti-acetylated tubulin antibody.

(D) Quantification of cerebellar measurements from the batches shown in (C).

(E) Representative dorsal images of 3 dpf larvae injected with gradually modified doses of WT and K94R RNA (top, amount in pg) and stained with anti-acetylated tubulin antibody.

(F) Quantification of cerebellar measurements from the batches shown in (E).

(G) Representative dorsal images of 3 dpf larvae injected either with e2i2 splice-blocking MO or MO co-injected with WT RORA mRNA, R462Q or population control T476A variant RORA mRNA.

(H) Quantification of cerebellar measurements from the batches shown in (E).

AU, arbitrary units. Stars indicate p value compared to WT. ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001; ns, not significant. Error bars in (B), (D), (F), and (H) represent the 5th and 95th percentiles.

Discussion

Here, we describe a cohort of 16 affected individuals who harbor 13 different rare variants disrupting RORA. We observe a clinical spectrum of neurodevelopmental delay with at least two different presentations: (1) a cognitive and motor phenotype and (2) a cognitive and behavioral phenotype. The first sub-phenotype is characterized by a moderate to severe ID with a marked ataxic component, severe cerebellar vermis hypoplasia, and epilepsy with predominant generalized seizures as already reported in RORB,3 whereas the hallmark of the second sub-phenotype is ASD with mild ID or normal cognition frequently associated with epilepsy. In addition to these two groups, three individuals exhibit only mild ID without behavioral problems.

Although the size of our cohort limits the delineation of an unambiguous genotype-phenotype correlation, we can infer pathomechanisms related to specific phenotypes from our in vivo complementation data. Individuals 2 and 3, who harbor the two dominant toxic mutations of the RORα DNA binding domain, display severe ID and motor phenotypes likely due to cerebellar hypoplasia. A similar severe phenotype is coincident with the truncating deletion (individual 6; p.Arg340Profs∗17), raising the possibility that this mutation could also result in a dominant toxic effect by encoding a truncated protein; immunoblotting studies from fibroblast protein lysates showed RORA protein levels to be similar to that of controls, arguing against haploinsufficiency (Figure S4C). Individual 6 also displayed autistic traits, but these phenotypes occurred secondary to established ID, potentially excluding her from the Autism Diagnosis Interview (ADI) criteria for idiopathic ASD.37, 38

By contrast, we note variability in cognitive function and behavioral phenotypes in individuals with likely haploinsufficiency. One individual displays an ASD phenotype in the absence of ID (individual 8), and in vivo complementation testing in zebrafish indicate that the p.Arg462Gln mutation confers a loss-of-function effect. Further, 6/12 individuals from simplex families who likely have a reduction in protein dosage display mild to moderate ID but with normal behavior, while the remaining 5/12 affected individuals from simplex families present with both ID and autistic features. Notably, there is phenotypic variability among the individuals within multiplex family 10: all four individuals display mild ID, but only two display behavioral anomalies. However, we cannot exclude the possibility of trans effects from elsewhere in the genome, especially from DISC1 affected by the CNVs harbored by individuals 10A–C or individual 11 (Figure S1; Table S4). Phenotypic variability is not uncommon for neurodevelopmental disorders,39 and here we account, in part, for variability due to allelism at the RORA locus by elucidating the direction of allele effect for missense changes.

The sub-group of our cohort who show a constellation of cognitive and motor defects are reminiscent of the homozygous staggerer (sg/sg) mouse, an early reported animal model of Rora ablation. The staggerer mutation consists of an intragenic CNV that results in a 122-bp frameshifting deletion that truncates the ligand binding domain, leading to the loss of RORα activity.8 This phenotype is similar to Rora−/− mice40 in which the most obvious symptom is an ataxic gait associated with defective Purkinje cell development leading to an abnormal cerebellar size.41 Heterozygous Rora+/− mice present with a comparable phenotype, although they display a late onset of neuronal loss and reduced phenotypic severity.42 Further studies will be required to understand the precise molecular mechanisms of p.Gly92Ala and p.Lys94Arg to account for their apparent toxic effects. We speculate that these changes in the DNA binding domain might hamper access of WT RORα to its natural target sites (Figure S3B), thereby leading to a phenotype resembling to the staggerer and Rora−/− homozygous mutants.

The autistic signs observed in two individuals with truncating mutations (individuals 6 and 13) and two individuals with missense mutations altering the ligand binding domain of RORA (individuals 7 and 8) are in agreement with recent reports suggesting that RORA is a candidate gene for ASD.43 ChIP-on-chip analysis has revealed that RORα can be recruited to the promoter regions of 2,544 genes across the human genome, with a significant enrichment in biological functions including neuronal differentiation, adhesion, and survival, synaptogenesis, synaptic transmission and plasticity, and axonogenesis, as well as higher-level functions such as development of the cortex and cerebellum, cognition, memory, and spatial learning.44 Independent ChIP-quantitative PCR analyses confirmed binding of RORA to promoter regions of selected ASD-associated genes, including A2BP1, CYP19A1, ITPR1, NLGN1, and NTRK2, whose expression levels are also decreased in RORA-repressed human neuronal cells and in prefrontal cortex tissues from individuals with ASD.44 Additionally, two RORA polymorphisms (rs11639084 and rs4774388) have been associated with ASD risk in Iranian individuals.45 Consistent with these data, treatment with a synthetic RORα/γ agonist, SR1078, reduced repetitive behavior in the BTBR mouse model of autism, suggesting that RORA upregulation could be a viable therapeutic option for ASD.46

In summary, our data implicate a diverse series of disruptive mutations in RORA with neurological phenotypes hallmarked by ID and either severe motor phenotypes or behavioral anomalies. Through combined clinical, genetic, and functional studies, we expand the genetic basis of rare neurodevelopmental syndromes and show how in vivo modeling can reveal dual molecular mutational effects.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. R. Hawkes and Dr. C. Armstrong (University of Calgary) for providing the zebrin II antibody. We also thank Mr. Z. Kupchinsky for zebrafish husbandry, Mr. D. Morrow for assisting with reagents for the in vivo modeling study, and members of the Center for Human Disease Modeling for helpful comments. We are also grateful to Ms. J.A. Rosenfeld (Mokry) for her precious help in our search for similar affected individuals and for her review of the manuscript. This work was supported by funds from the Agence Nationale pour la Recherche/E-rare Joint-Transnational-Call 2011 (2011-RARE-004-01 “Euro-SCAR”) to M.K.; from the National Human Genome Research Institute with supplemental funding provided by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute under the Trans-Omics for Precision Medicine (TOPMed) program and the National Eye Institute (to the Broad Center for Mendelian Genomics [UM1 HG008900]); from the NIH grant T32 HD07466 (to M.H.W.); US NIH grant R01 MH106826 to E.E.D.; and from the Estonian Research Council, grant PUT355 (to S.P. and K.Õ.). We also acknowledge the Deciphering Developmental Disorders (DDD) Study.

K.M., M.T.C., R.W., M.J.G.S., and K.R. are employees of GeneDx, Inc., a wholly owned subsidiary of OPKO Health, Inc. N.K. is a paid consultant for and holds significant stock of Rescindo Therapeutics, Inc.

Published: April 12, 2018

Footnotes

Supplemental Data include ten figures and four tables and can be found with this article online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2018.02.021.

Contributor Information

Erica E. Davis, Email: erica.davis@duke.edu.

Sébastien Küry, Email: sebastien.kury@chu-nantes.fr.

Web Resources

1000 Genomes, http://www.internationalgenome.org/

CHOPCHOP, http://chopchop.cbu.uib.no/

Clustal: Multiple Sequence Alignment, http://www.clustal.org/

Database of Genomic Variants (DGV), http://dgv.tcag.ca/dgv/app/home

DECIPHER, https://decipher.sanger.ac.uk/

Ensembl Genome Browser, http://www.ensembl.org/index.html

ExAC Browser, http://exac.broadinstitute.org/

GeneMatcher, https://genematcher.org/

gnomAD Browser, http://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/

ImageJ Fiji, http://fiji.sc/Fiji

NHLBI Exome Sequencing Project (ESP) Exome Variant Server, http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/

OMIM, http://www.omim.org/

QuickChange Primer Design, https://www.genomics.agilent.com/primerDesignProgram.jsp

The Human Protein Atlas, http://www.proteinatlas.org/

UCSC Genome Browser, http://genome.ucsc.edu

UniProt, http://www.uniprot.org/

ZFIN, http://zfin.org

Supplemental Data

References

- 1.Escriva H., Langlois M.C., Mendonça R.L., Pierce R., Laudet V. Evolution and diversification of the nuclear receptor superfamily. Ann. N Y Acad. Sci. 1998;839:143–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb10747.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sladek F.M. What are nuclear receptor ligands? Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2011;334:3–13. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2010.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rudolf G., Lesca G., Mehrjouy M.M., Labalme A., Salmi M., Bache I., Bruneau N., Pendziwiat M., Fluss J., de Bellescize J. Loss of function of the retinoid-related nuclear receptor (RORB) gene and epilepsy. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2016;24:1761–1770. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2016.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Okada S., Markle J.G., Deenick E.K., Mele F., Averbuch D., Lagos M., Alzahrani M., Al-Muhsen S., Halwani R., Ma C.S. IMMUNODEFICIENCIES. Impairment of immunity to Candida and Mycobacterium in humans with bi-allelic RORC mutations. Science. 2015;349:606–613. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa4282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bardoni B., Zanaria E., Guioli S., Floridia G., Worley K.C., Tonini G., Ferrante E., Chiumello G., McCabe E.R., Fraccaro M. A dosage sensitive locus at chromosome Xp21 is involved in male to female sex reversal. Nat. Genet. 1994;7:497–501. doi: 10.1038/ng0894-497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Muscatelli F., Strom T.M., Walker A.P., Zanaria E., Récan D., Meindl A., Bardoni B., Guioli S., Zehetner G., Rabl W. Mutations in the DAX-1 gene give rise to both X-linked adrenal hypoplasia congenita and hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. Nature. 1994;372:672–676. doi: 10.1038/372672a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Giguère V., Tini M., Flock G., Ong E., Evans R.M., Otulakowski G. Isoform-specific amino-terminal domains dictate DNA-binding properties of ROR alpha, a novel family of orphan hormone nuclear receptors. Genes Dev. 1994;8:538–553. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.5.538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hamilton B.A., Frankel W.N., Kerrebrock A.W., Hawkins T.L., FitzHugh W., Kusumi K., Russell L.B., Mueller K.L., van Berkel V., Birren B.W. Disruption of the nuclear hormone receptor RORalpha in staggerer mice. Nature. 1996;379:736–739. doi: 10.1038/379736a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yamamoto T., Mencarelli M.A., Di Marco C., Mucciolo M., Vascotto M., Balestri P., Gérard M., Mathieu-Dramard M., Andrieux J., Breuning M. Overlapping microdeletions involving 15q22.2 narrow the critical region for intellectual disability to NARG2 and RORA. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 2014;57:163–168. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2014.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boutry-Kryza N., Labalme A., Till M., Schluth-Bolard C., Langue J., Turleau C., Edery P., Sanlaville D. An 800 kb deletion at 17q23.2 including the MED13 (THRAP1) gene, revealed by aCGH in a patient with a SMC 17p. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2012;158A:400–405. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.34222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grønborg S., Kjaergaard S., Hove H., Larsen V.A., Kirchhoff M. Monozygotic twins with a de novo 0.32cMb 16q24.3 deletion, including TUBB3 presenting with developmental delay and mild facial dysmorphism but without overt brain malformation. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2015;167A:2731–2736. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.37227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sali A., Blundell T.L. Comparative protein modelling by satisfaction of spatial restraints. J. Mol. Biol. 1993;234:779–815. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Obholzer N., Wolfson S., Trapani J.G., Mo W., Nechiporuk A., Busch-Nentwich E., Seiler C., Sidi S., Söllner C., Duncan R.N. Vesicular glutamate transporter 3 is required for synaptic transmission in zebrafish hair cells. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:2110–2118. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5230-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Montague T.G., Cruz J.M., Gagnon J.A., Church G.M., Valen E. CHOPCHOP: a CRISPR/Cas9 and TALEN web tool for genome editing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42 doi: 10.1093/nar/gku410. W401-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Küry S., Besnard T., Ebstein F., Khan T.N., Gambin T., Douglas J., Bacino C.A., Craigen W.J., Sanders S.J., Lehmann A. De novo disruption of the proteasome regulatory subunit PSMD12 causes a syndromic neurodevelopmental disorder. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2017;100:352–363. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2017.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stankiewicz P., Khan T.N., Szafranski P., Slattery L., Streff H., Vetrini F., Bernstein J.A., Brown C.W., Rosenfeld J.A., Rednam S., Deciphering Developmental Disorders Study Haploinsufficiency of the chromatin remodeler BPTF causes syndromic developmental and speech delay, postnatal microcephaly, and dysmorphic features. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2017;101:503–515. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2017.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ta-Shma A., Khan T.N., Vivante A., Willer J.R., Matak P., Jalas C., Pode-Shakked B., Salem Y., Anikster Y., Hildebrandt F. Mutations in TMEM260 cause a pediatric neurodevelopmental, cardiac, and renal syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2017;100:666–675. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2017.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Niederriter A.R., Davis E.E., Golzio C., Oh E.C., Tsai I.-C., Katsanis N. In vivo modeling of the morbid human genome using Danio rerio. J. Vis. Exp. 2013:e50338. doi: 10.3791/50338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Margolin D.H., Kousi M., Chan Y.-M., Lim E.T., Schmahmann J.D., Hadjivassiliou M., Hall J.E., Adam I., Dwyer A., Plummer L. Ataxia, dementia, and hypogonadotropism caused by disordered ubiquitination. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;368:1992–2003. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1215993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schneider C.A., Rasband W.S., Eliceiri K.W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:671–675. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sobreira N., Schiettecatte F., Valle D., Hamosh A. GeneMatcher: a matching tool for connecting investigators with an interest in the same gene. Hum. Mutat. 2015;36:928–930. doi: 10.1002/humu.22844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ruff M., Gangloff M., Wurtz J.M., Moras D. Estrogen receptor transcription and transactivation: Structure-function relationship in DNA- and ligand-binding domains of estrogen receptors. Breast Cancer Res. 2000;2:353–359. doi: 10.1186/bcr80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sidman R.L., Lane P.W., Dickie M.M. Staggerer, a new mutation in the mouse affecting the cerebellum. Science. 1962;137:610–612. doi: 10.1126/science.137.3530.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marin-Valencia I., Novarino G., Johansen A., Rosti B., Issa M.Y., Musaev D., Bhat G., Scott E., Silhavy J.L., Stanley V. A homozygous founder mutation inTRAPPC6B associates with a neurodevelopmental disorder characterised by microcephaly, epilepsy and autistic features. J. Med. Genet. 2018;55:48–54. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2017-104627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schaffer A.E., Eggens V.R.C., Caglayan A.O., Reuter M.S., Scott E., Coufal N.G., Silhavy J.L., Xue Y., Kayserili H., Yasuno K. CLP1 founder mutation links tRNA splicing and maturation to cerebellar development and neurodegeneration. Cell. 2014;157:651–663. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Borck G., Hög F., Dentici M.L., Tan P.L., Sowada N., Medeira A., Gueneau L., Thiele H., Kousi M., Lepri F. BRF1 mutations alter RNA polymerase III-dependent transcription and cause neurodevelopmental anomalies. Genome Res. 2015;25:155–166. doi: 10.1101/gr.176925.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Akizu N., Cantagrel V., Zaki M.S., Al-Gazali L., Wang X., Rosti R.O., Dikoglu E., Gelot A.B., Rosti B., Vaux K.K. Biallelic mutations in SNX14 cause a syndromic form of cerebellar atrophy and lysosome-autophagosome dysfunction. Nat. Genet. 2015;47:528–534. doi: 10.1038/ng.3256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Frosk P., Arts H.H., Philippe J., Gunn C.S., Brown E.L., Chodirker B., Simard L., Majewski J., Fahiminiya S., Russell C., FORGE Canada Consortium. Canadian Rare Diseases: Models & Mechanisms Network A truncating mutation in CEP55 is the likely cause of MARCH, a novel syndrome affecting neuronal mitosis. J. Med. Genet. 2017;54:490–501. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2016-104296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anttonen A.-K., Laari A., Kousi M., Yang Y.J., Jääskeläinen T., Somer M., Siintola E., Jakkula E., Muona M., Tegelberg S. ZNHIT3 is defective in PEHO syndrome, a severe encephalopathy with cerebellar granule neuron loss. Brain. 2017;140:1267–1279. doi: 10.1093/brain/awx040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hibi M., Shimizu T. Development of the cerebellum and cerebellar neural circuits. Dev. Neurobiol. 2012;72:282–301. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bertrand S., Thisse B., Tavares R., Sachs L., Chaumot A., Bardet P.-L., Escrivà H., Duffraisse M., Marchand O., Safi R. Unexpected novel relational links uncovered by extensive developmental profiling of nuclear receptor expression. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e188. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Katsuyama Y., Oomiya Y., Dekimoto H., Motooka E., Takano A., Kikkawa S., Hibi M., Terashima T. Expression of zebrafish ROR alpha gene in cerebellar-like structures. Dev. Dyn. 2007;236:2694–2701. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hamling K.R., Tobias Z.J.C., Weissman T.A. Mapping the development of cerebellar Purkinje cells in zebrafish. Dev. Neurobiol. 2015;75:1174–1188. doi: 10.1002/dneu.22275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gold D.A., Gent P.M., Hamilton B.A. ROR alpha in genetic control of cerebellum development: 50 staggering years. Brain Res. 2007;1140:19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.11.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vogel M.W., Sinclair M., Qiu D., Fan H. Purkinje cell fate in staggerer mutants: agenesis versus cell death. J. Neurobiol. 2000;42:323–337. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4695(20000215)42:3<323::aid-neu4>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yoon C.H. Developmental mechanism for changes in cerebellum of “staggerer” mouse, a neurological mutant of genetic origin. Neurology. 1972;22:743–754. doi: 10.1212/wnl.22.7.743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tammimies K., Marshall C.R., Walker S., Kaur G., Thiruvahindrapuram B., Lionel A.C., Yuen R.K.C., Uddin M., Roberts W., Weksberg R. Molecular diagnostic yield of chromosomal microarray analysis and whole-exome sequencing in children with autism spectrum disorder. JAMA. 2015;314:895–903. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.10078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chérot E., Keren B., Dubourg C., Carré W., Fradin M., Lavillaureix A., Afenjar A., Burglen L., Whalen S., Charles P. Using medical exome sequencing to identify the causes of neurodevelopmental disorders: Experience of 2 clinical units and 216 patients. Clin. Genet. 2018;93:567–576. doi: 10.1111/cge.13102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hu W.F., Chahrour M.H., Walsh C.A. The diverse genetic landscape of neurodevelopmental disorders. Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 2014;15:195–213. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genom-090413-025600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Doulazmi M., Frédéric F., Capone F., Becker-André M., Delhaye-Bouchaud N., Mariani J. A comparative study of Purkinje cells in two RORalpha gene mutant mice: staggerer and RORalpha(-/-) Brain Res. Dev. Brain Res. 2001;127:165–174. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(01)00131-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Herrup K., Shojaeian-Zanjani H., Panzini L., Sunter K., Mariani J. The numerical matching of source and target populations in the CNS: the inferior olive to Purkinje cell projection. Brain Res. Dev. Brain Res. 1996;96:28–35. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(96)00069-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Doulazmi M., Capone F., Frederic F., Bakouche J., Lemaigre-Dubreuil Y., Mariani J. Cerebellar purkinje cell loss in heterozygous rora+/- mice: a longitudinal study. J. Neurogenet. 2006;20:1–17. doi: 10.1080/01677060600685832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nguyen A., Rauch T.A., Pfeifer G.P., Hu V.W. Global methylation profiling of lymphoblastoid cell lines reveals epigenetic contributions to autism spectrum disorders and a novel autism candidate gene, RORA, whose protein product is reduced in autistic brain. FASEB J. 2010;24:3036–3051. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-154484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sarachana T., Hu V.W. Genome-wide identification of transcriptional targets of RORA reveals direct regulation of multiple genes associated with autism spectrum disorder. Mol. Autism. 2013;4:14. doi: 10.1186/2040-2392-4-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sayad A., Noroozi R., Omrani M.D., Taheri M., Ghafouri-Fard S. Retinoic acid-related orphan receptor alpha (RORA) variants are associated with autism spectrum disorder. Metab. Brain Dis. 2017;32:1595–1601. doi: 10.1007/s11011-017-0049-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang Y., Billon C., Walker J.K., Burris T.P. Therapeutic effect of a synthetic RORα/γ agonist in an animal model of autism. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2016;7:143–148. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.5b00159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.