Abstract

Conventional and Alternative Medicine (CAM) is popularly used due to side-effects and failure of approved methods, for diseases like Epilepsy and Cancer. Amygdalin, a cyanogenic diglycoside is commonly administered for cancer with other CAM therapies like vitamins and seeds of fruits like apricots and bitter almonds, due to its ability to hydrolyse to hydrogen cyanide (HCN), benzaldehyde and glucose. Over the years, several cases of cyanide toxicity on ingestion have been documented. In-vitro and in-vivo studies using various doses and modes of administration, like IV administration studies that showed no HCN formation, point to the role played by the gut microbiota for the commonly seen poisoning on consumption. The anaerobic Bacteriodetes phylum found in the gut has a high β-glucosidase activity needed for amygdalin hydrolysis to HCN. However, there are certain conditions under which these HCN levels rise to cause toxicity. Case studies have shown toxicity on ingestion of variable doses of amygdalin and no HCN side-effects on consumption of high doses. This review shows how factors like probiotic and prebiotic consumption, other CAM therapies, obesity, diet, age and the like, that alter gut consortium, are responsible for the varying conditions under which toxicity occurs and can be further studied to set-up conditions for safe oral doses. It also indicates ways to delay or quickly treat cyanide toxicity due to oral administration and, reviews conflicts on amygdalin's anti-cancer abilities, dose levels, mode of administration and pharmacokinetics that have hindered its official acceptance at a therapeutic level.

Keywords: Amygdalin, β-glucosidase, Bacteriodetes, Gut microbes, Hydrogen cyanide, Rhodanese

1. Introduction

Combined surgery, radiation therapy and chemotherapy are the commonly used cancer treatments that people turn to, when first diagnosed with cancer. These treatments give a better prognosis but, cases of toxicity and failure of such methods are not uncommon [1]. In such cases, people tend to turn to alternative treatments, also known as CAM (conventional and alternative medicine), claimed to be fruitful as a single or combined treatment [2], [3]. Amygdalin is naturally occurring cyanogenic glycoside compound present in fruits and seeds of fruits like apricot, peaches and bitter almonds and it was falsely considered as vitamin and was used for cancer treatment in late 1950s. Eating amygdalin will cause cyanide poison as amygdalin molecule has nitrile group and could be released as cyanide anion due to the action of beta-glucosidase in human body. Laetrile is a man made synthetic compound from natural amygdalin and was also used for anticancer treatment during 1970s [2].

When NCI carried out 22 case studies pertaining to the use of Laetrile as an alternative therapy,6 successful cases were found and the FDA banned the use of Laetrile in 1979 [2], [4]. Several cases of toxicity have been reported due to the consumption of amygdalin which caused cyanide toxicity (Table 1). An instance of hydrogen cyanide toxicity in animals was first reported in cattle due to consumption of Holocalyx Glaziovii leaves (found in Brazil, Argentina and Paraguay) due to prunasin, another cyanoglycoside, and was later confirmed by Silvana et al. in Wistar rats [5].

Table 1.

Cyanide toxicity cases reported due to oral ingestion of amygdalin [3], [6], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28].

| Toxicity victim | Cause, symptoms and effects |

|---|---|

| 67 year old woman (1983) | Consumed laetrile tablets for cancer treatment along with bitter almonds. Led to demyelination and axonal degredation. Recovered via IV administration of sodium nitrite and sodium thiosulfate |

| 28 month old girl (2011) | Unconsciousness and seizures after ingestion of 10 apricot seeds. Died after 22 days with whole blood cyanide levels of around 3 mg/L |

| 32 year old female | Consumed amygdalin supplements. Developed systemic toxicity as well as diabetes insipidus but, recovered with appropriate therapy |

| 4 year old child with malignant brain disease (metastatic ependymoma) | Given standardoncology therapy as well as several alternate therapies like apricot kernels, oral and IV administration of amygdalin and vitamins. Life threatening toxicity symptoms developed. Recovered in three days with thiosulfate administration. |

| 41 year old, healthy, non-smoking adult (1998) | Chewed and swallowed around 30 apricot kernels (15 g approximately). Developed initial symptoms in 20 min. Amyl nitrate via inhalation and sodium nitrite and thiosulfate via IV helped in recovery. |

| 28 year old man, vegetarian, non-smoker, non-drinker (2003) | Taking a herbal concoction with peach seed extract. Due to vitamin B12 deficiency and amygdalin presence, led to peripheral neuropathy |

| 35 year old woman, mentally ill | Consumed 20–30 apricot kernels. Suffered from the initial toxicity symptoms and was hypotensive, hypoxic and tachypnoeic. Recovered due to treatment with sodium nitrite and sodium thiosulfate followed by hydroxocobalamin |

| 48 year old man, was in comatose | Ingested 25 g of potassium cyanide. IV administration of hydroxocobalamin aided in recovery |

| 23 year old girl, was convulsing | Had a teaspoon of potassium cyanide. Was treated with hyperbaric oxygen along with IV administration of sodium thiosulfate |

Various animal studies and cases of human consumption point out the danger of oral administration of amygdalin [5], [6]. Table 8 shows how the activity of intestinal microflora upon these cyanoglycosides has been proved to lead to the formation of hydrogen cyanide (HCN) [2], [7]. One of the first studies to prove this employed cycasin, a cyanogenic glycoside. It was administered orally and via the parenteral route to conventional rats and, orally to germ free rats. It was seen to be ineffective in germ free and parenteral rats, indicating importance of microbial activity on hydrolysing glycosides to simple sugars [8]. On the genus level, Bacteriodetes species are the most abundant and are mainly involved in glucosidase production, an enzyme required to breakdown amygdalin into cyanide [9].

Table 8.

| Research experiment | Observations and results |

|---|---|

| Veibel (1950) and Hildebrand and Schroth (1964) | Showed high β-glucosidase production in various bacterial strains |

| Reitnauer (1972), IV and oral administration of amygdalin to mice | 69.3% of IV and 19.5% of oral doses were obtained unconverted in the urine |

| Greenberg (1975) | Proposed amygdalin will be excreted almost unchanged on parenteral administration |

| Ames et al. (1978), parenteral administration of amygdalin in man | Excreted almost completely unchanged |

| Carter et al. (1980), fed germ free and conventional rats daily doses of 600 mg/kg of amygdalin | None of the effects of cyanide toxicity were observed in the germ free rats, with large amounts of unconverted amygdalin obtained in feces. Conventional rats showed high blood cyanide levels, thiocyanate levels and death within 2–5 h |

| Greenberg (1975) | He reports that it is believed that body tissues produce low quantities of β-glucosidase which is why parenteral administration leads to excretion of mainly unconverted amygdalin while, due to gut microbial glucosidase activity, cyanide toxicity can occur |

IV administration of amygdalin showed no such effect [6]. Milazzo et al. report two studies, one employs IV administration of Laetrile and the other, application of Laetrile on tumour sites. Both show improved survival rate but not complete positive response in cancer patients [2]. No HCN toxicity was reported in either of the cases, suggesting that it is prevalent solely during oral consumption [4]. Around 80% of thiocyanate (after detoxification by Rhodanese enzyme) and some amounts of parent drug can be found in urine after IV and subcutaneous administration [10], [11].

Studies have been carried out to prove the benefit of amygdalin to cancer patients but, due to conflicting results, side effects and lack of improvement on survival rate, many feel that the risk to benefit ratio for this compound is too high [2], [6], [12].

2. Important components of the equation

2.1. Amygdalin

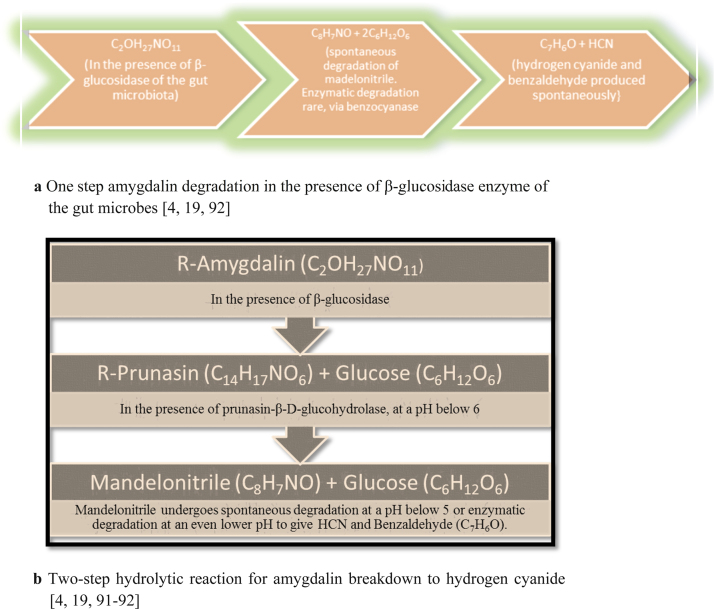

A cyanogenic-diglycoside, amygdalin (D-mandelonitrile-β-D-glucosido-6-β-D-glucoside) is commonly found in stone fruits and berries like apricots, plums, peaches, apples, papaya and cherries and also in plants like rice, unripe sugarcane, sorghum, certain species of nuts and yam in combination with other cyanogenic glycosides like Linamarin [13], [14], [15], [16], [17]. Sometimes, it is also found in the leaves and foliage of plants like Saskatoon berries and mature trees of the Prunus taxa [13], [18]. Aromatic compounds like benzyl alcohol, benzoic acid and benzaldehylde are also commonly found in such fruits [13]. Studies show that amygdalin undergoes enzymatic hydrolysis and is converted to two glucose molecules as well as mandelonitrile, which due to its unstable nature, is spontaneously converted to HCN and benzaldehyde, as observed in Fig. 1 [13], [14], [19]. This benzaldehyde, which commonly helps impart aroma to the fruit, can be further oxidised to benzoic acid and, the HCN is capable of causing toxicity, if amygdalin is orally ingested, by inhibiting the cytochrome oxidase of the Electron Transport Chain (ETC) in the mitochondria [13], [14].

Fig. 1.

a One step amygdalin degradation in the presence of β-glucosidase enzyme of the gut microbes [4], [19], [92]. b Two-step hydrolytic reaction for amygdalin breakdown to hydrogen cyanide [4], [19], [91], [92].

Enzymatic hydrolysis of amygdalin is known to be accelerated in the presence of heat. Water also plays a role in bringing the substrate and enzyme in close proximity. An instance is in fruits like cherries where, increasing the temperature up to 65 °C, hydrolyses benzaldehyde, due to the accelerated action of amygdalin hydrolase, prunasin lyase, β-glucosidase, water and mandelonitrile lyase [13]. In animals, vitamin C is known to have the same effect on amygdalin, as it alternates blood cysteine levels, leading to a decrease in detoxification of HCN by decreasing Rhodanese activity [6]. Those with cyanocobalamin deficiency or genetic inability for detoxification are also prone to increased blood cyanide levels [2], [6]. Clinical dose of amygdalin tobe taken should not exceed 680 mg/kg [20].

2.2. Laetrile

First synthesised by Krebs and termed as vitamin B17, laetrile is an acronym for the terms laevorotatory and mandelonitrile [2], [11]. Initially utilised as an alternative cancer therapy in Russia and then in the USA, around 1920s, it was patented by the USA as D-mandelonitrile-β-glucuronide. It is also popular in Mexico but, the compound used is D-mandelonitrile-β-gentiobioside (has two glucose molecules combined through hydroxyl positions 1 and 6) [2], [29]. Laetrile therapy is usually taken in combination with other CAM proponents, like diet, urine, metabolic and oral therapy, β-glucuronidase injections and intake of fruit seeds [2]. Laetrile, unlike amygdalin, has only one glucose molecule [16]. It has 6% cyanide by weight. If eaten with foods that have β-glucosidase, combined with gut-flora composition, it leads to cyanide toxicity which can occur in three stages as mentioned in Table 2 [30].

Table 2.

| Initial symptoms (whole blood cyanide levels of 0.5–1.0 mg/L) | Headache, nausea, metallic taste, drowsiness, dizziness, anxiety, mucous membrane irradiation, hyperpnea |

| Later symptoms (whole blood cyanide levels of above 1.0 mg/L) | Arrhythmias, periods of cyanosis and unconsciousness, bradycardia, hypotension and dyspnea |

| Severe poisioning (whole blood cyanide levels of 2.5–3.0 mg/L) | Progressive coma, convulsions, edema, cardiovascular collapse with shock |

2.3. Rhodanese

Mainly catalysing the formation of thiocyanate from cyanide and thiosulfate, Rhodanese (thiosulfate sulfurtransferase) is found in a variety of plants and animals (differs based on various factors such as sex, organs, diet, age and species) with properties as described in Table 3 [14], [31]. It is believed that rhodanese distribution in animal tissues depends on cyanide exposure since the primary function of this enzyme is believed to be cyanide detoxification. In animals, it is found as amitochondrial enzyme as shown by Mimori et al.on rat brain [14], [31], [32], [33].

Table 3.

| Molecular Weight | 37,000 |

| Number of Amino Acids | 289 |

| Optimum pH | 8 |

| Optimu Temperature | 45 °C for five minutes and 55 °C in the presence of thiosulfate for extended periods |

| Active Site components | Tryptophanyl residue in close proximity with a sulphahydryl (-SH) group. |

| Mechanism of Action | Ping-Pong Mechanism- a sulphur atom is transferred from thiosulfate to an active site cysteine thiol. Sulfite, is released. Then cyanide reacts with enzyme-bound persulfide, forming thiocyanate |

| Location | Mitochondria of liver (in mammals). Liver, kidneys, muscles and brain (rats). Epithelium of rumen and liver (camel and goat). Respiratory systems (sheep and dog). None in red blood cells. Also found in leaves of plants like cassava |

| Commonly found forms | Dephospho and phospho rhodanese ( have identical amino acids, kinetic parameters, molecular weights and sulphahydryl content) |

| Main function in animals | To convert highly toxic cyanide to less toxic thiocyanate |

| Main function in plants | Cyanide detoxification |

| Michaelis-Mentes constant | 3 mM |

| Inhibited by | Ascorbic acid (vitamin C), iodine, alloxan, hydrogen peroxide, mercaptans, aromatic nitro compounds, alkylating agents |

| Detection Method | Calorimetric determination of thiosulfate in-vitro |

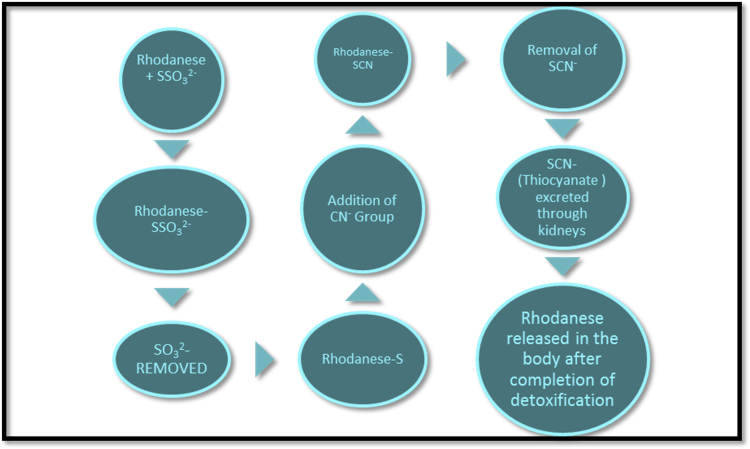

It interacts with mitochondrial membrane bound iron sulphur centres (of the mitochondrial ETC) and modulates the rate of respiration in cells [11], [14], [31], [32]. The sulphahydryl group of the active site could form an intramoleclar disulphide linkage with another of its kind but, it is hindered due to close proximity with aromatic groups [14], [40]. However, these groups can form hydrophobic interactions [14]. The thiosulfate acts as a sulphur donor in HCN detoxification [11], [14], [31]. As seen in Fig. 2, Rhodanese transfers sulfane atoms from this donor to a thiophilic acceptor [32], [42]. Sometimes, even cystine and methionine act as sulphur donors [11], [31]. This detoxified HCN is excreted through the kidneys as thiocyanate [11], [14], [42]. Studies have reported that malignant cells are deficient in Rhodanese [2].

Fig. 2.

Detoxification of cyanide in the body via action of Rhodanese enzyme [14], [41].

2.4. β-Glucosidase

Also known as carbohydrate activating or hydrolytic lysosomal enzyme, β-glucosidase having differential properties (Table 4) releases benzaldehyde, glucose and HCN from amygdalin, which has glycosidic linkages [2], [11], [43]. Laetrile is broken down by β-glucuronidase due to the presence of a glucuronide group [2]. When this HCN is released, it enters the cell, inhibits cytochrome oxidase C by reacting with the ferric iron group during mitochondrial respiration, due to its ability to form complexes with metal ions and leads to cell lysis by inhibiting ATP synthesis. It can also lyse cells by destroying lysosymes due to increasing acid content [2], [11], [44].

Table 4.

| Molecular weight | 40–250 kDa |

| pH | 3.5–5.5, most active at 5 |

| Main function in plants and animals | To cleave the β glycosidic bond between aryl and saccharide groups (1,4, 1,2 and 1,6) thereby releasing glucose. |

| Location | Released by gut microbiota, microbes like black aspergilli and found in commonly eaten plants like in apricot kernels(which are also rich in antioxidants) and is called emulsion, nuts like almonds, vegetables like mushrooms, lettuce and green peppers |

| Inhibition assays in-vitro | Cellobioimidazole |

| (CBI), glucosylsphingosine and fluoromethyl cellobiose (FMCB) | |

| Activation assay in-vitro | Use of bile acids along with cholic acid |

| Commercial uses | Mainly used as a cell factory for cellulose hydrolysis. Thermostable glucosidases are used to produce glucose from cellooloigosaccharides at temperatures as high as 90 °C. Can be used to produce beneficial aglycnes from isoflavones. |

Malignant cells have large quantities of β- glucosidase and β- glucuronidase (as found in urine, tissue and blood serum samples of cancer patients, and murine studies carried out by Manner et al.). Cancer cells are dominant in anaerobic glycosis and β-glucosidase is most active in lactate induced acidic conditions [2], [16], [44]. This ultimately leads to the release of HCN, if amygdalin is present near the cancer cells. A study by LI Yun-long et al., using monoclonal antibodies targeting β-glucosidase and amygdalin to cancer cells showed positive cell lysis, confirming HCN and β-glucosidaseactivities in cancer therapy [44].

3. Gut microbial flora

Bacteria are highly diverse and dominant in the gastro intestinal tract (GIT), with around 1014 bacteria and 500 different species, dominated by the anaerobes. They are classified as three types based on their properties as given in Table 5 [52], [53]. They not only play an important role in the metabolic processes and nutrient conversion but also as pathogenic factors in diseases like obesity [54]. The microbes have a microbiome which is 100 times larger than the human genome and they start growing during birth. The first week of life has aerobes that utilize oxygen and set up conditions for anaerobes. They rapidly alter due to various factors and are fully established by 4 years. The main members are the Firmicutes, Bacteriodetes and Actinobacteria which contribute to cyanide release [54].

Table 5.

| Firmicutes | Bacteriodetes | Actinobacteria |

|---|---|---|

| Gram positive | Gram negative | Gram positive |

| Dominant in large intestine | Dominant in large intestine | Dominant in large intestine |

| 64% | 23% | 3% |

| Detected via RNA sequencing | Detected via RNA sequencing | Detected via FISH |

| Anaerobic | Anaerobic | Anaerobic |

Intestinal microbiota obtain their nutrition by hydrolysis of sulfates, amides, glucuronidases, esters and lactones through the action of enzymes that the produce such as sulfatase, esterase, α-rhamnosidase, β-glucosidase and β-glucuronidase [20]0.16 s rRNA sequencing can be used to identify human gut microbiota [55]. A Human Microbiome Project (HMP) has been established by NIH to characterise the mammalian microbiota [56]. (Table 6, Table 7, Table 8, Table 9, Table 10).

Table 6.

Factors affecting gut microbial composition [20].

| Mode of infant delivery |

| Antibiotic exposure |

| Neonatal and adult nutrition |

| Stress |

| Age |

| Degree of hygiene |

| Genetic factors |

| Mother's genetic make-up |

Table 7.

Types of Digestion [64].

| Genuine Digestion | Performed mainly in the stomach by the organisms own enzymes. |

| Autolytic Digestion | Occurs due to the food's own enzymes. |

| Symbiotic Digestion | Takes place due to the metabolic activity of the symbiotic microbes within the host organism. |

Table 9.

| Activating | Inhibiting |

|---|---|

| Animal protein | High fibre |

| Certain amino acids | Vegan and vegetarian diets |

| Saturated fats (like in meats) | Tea phenolics and their derivatives |

| Polysaccharides (like cellulose and hemicellulose) | Red wine polyphenols (alglycones of rutin, hesperidin and Naringin) |

| Tannin rich diet |

Table 10.

Commercially available Laetrile products [94,95].

| Product name | Active ingredient | Source of laetrile | Method of administration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Novodalin | Laetrile | Extracted from raw apricot kernels | Oral-500 mg tablets |

| Amigdalina | Laetrile | Extracted from apricot kernels | Liquid I.V. vials |

| Vita B17 cream | Laetrile | Extracted from apricot kernels | To be applied as a cream for external use on skin |

| Amygdatrile | Laetrile | Extracted from apricot kernels | Oral-100 mg capsules |

4. Prebiotics and probiotics

Prebiotics are compounds like certain lipids, proteins, carbohydrates and peptidases that help initiate specific changes in the activity and composition of the gut-microbiota, thus propagating well-being and health of the host [20]. Probiotics are organisms like Lactobacillus and Bifedobacterium, which help modulate intestinal bacterial enzymes and absorb or bind carcinogens [57], [58], [59]. They are safe for consumption to promote a healthy gut health and to avoid cyanide toxicity due to amygdalin breakdown. Steer et al. have shown how fructo-oligosaccharides increase the amount of Lactobacillus and bifidobacteria in vitro [60].

5. The microbiome and orally administered amygdalin

When consumed orally, a drug is influenced by enzymes of the GIT lumen, gut wall, hepatic and gut microbiome [61]. Enzymes of the microflora, gut nucleases and lipases as well as transferases, peptidases, cytochrome P450 and proteases influence metabolism of drugs and nutrients [61]. Lower blood flow of the intestinal mucosa increases residence time of drugs in the enterocytes. Also, the brush border bound glycosidases which can cleave a glycosidic linkage, does not contribute much to the metabolism of orally administered drugs due to its requirement to bind to highly specific cleavage sites [61]. These two factors are what are responsible for the lack of germ free animals to lead to cyanide toxicity on oral administration of amygdalin. Two mammalian β-glucosidases found in the mucosa of the brush border in the intestine is Lactasephlorizin hydrolase (LPH) and cytosolic β-glucosidase (CBG), which can also act on bile and fatty acids to produce carcinogens [62], [63], [90]. Due to low intestinal enzymatic activity, the compounds that do not act as substrates go down to the colon and are acted upon by the gut microbial enzymes.β-glucosidases present in kernels are also responsible for amygdalin hydrolysis [4].

The gut microbial flora also determines the degree of toxicity and whole blood cyanide levels [21]. They have high βglucosidase activities, predominantly the Bacteriodetes, and release cyanide via symbiotic digestion of Amygdalin [4].

It has been shown that the intestinal and microbial β-glucosidases have different substrates. Antibiotic treatment has shown a decrease in gut-flora but, when given amygdalin, only prunasin and no HCN was found. This shows that intestinal enzymes hydrolyse amygdalin only to prunasin, which goes down to the colon,is acted upon by the microbial β-glucosidase and completely hydrolysed [4]. The gut microbiota is difficult to quantify with conventional techniques, making it hard to find the consortium of each individual and speculate on individual dose toxicity and efficacy [65]. Zhang et al. found that the gut microbiota of a polysaccharide consuming termite predominantly had members of the Bacteriodetes species. They were found to be a rich source of β-glucosidase genes. It was shown that even in the human gut, Bacteriodetes produce β-glucosidase enzyme, which plays an important role in hemicellulose or cellulose degradation due to its function as a cellulose hydrolase [43]. In fact, studies on germ free and control rats have shown that the gut microbiome leads the host to increase glucose and tri acyl glycerol production [36]. This could explain why amygdalin is actively hydrolysed, due to its glucose content.

It has been observed in obese and non-obese patients, that with an increase in body weight, Bacteriodetes to Firmicutes ratio decreases although, Dumah et al. and Zhang et al. found no difference in the ratio [20], [54], [66]. High fibre diets like those in Europe and rural Africa show a good Bacteriodetes population in the gut [66]. This suggests that interactions between diet, immune system, gut microbiota and metabolism have great impacts on health as well as metabolic activity of the bacteria [20]. Lactulose, a commonly used prebiotic, is also known to decrease the amount of β-glucosidase producing Bacteriodetes [20]. Animal studies have shown a decrease in β-glucuronidase levels on consumption of probiotics containing Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium supplements, thus indicating a decrease in levels of β-glucuronidase encoding Bacteriodetes species [57], [64]. Studies have shown a lower activity of β-glucosidase and β-glucuronidase in Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium as compared to Bacteriodetes [67]. A DMH model was used to show a decreased activity of both the enzymes in-case of Lactobacillus Acidophilus and Lactobacillus GG, while it showed increased activity for Bacteriodetes fragilis, which has the highest β-glucosidase activity [4], [67]. Older people tend to have high levels of Lactobacillus, enterococci, clostridia and enterobacteria compared to other microbes [68]. Ravcheev et al., used comparative genomic studies for Bacteriodetes thetaiotaomicron and showed the presence of 269 glycoside hydrolases, with glucuronidase and glucosidase genes also present [9], [69]. Patel and Goyal showed that administration of nutritionally rich foods like CAM30 or blackcurrant extract lead to a decrease in Bacteriodetes content as well as levels of β-glucosidase, proving again the production of this enzyme mainly by this particular phylum [70]. Karlsson et al. have reported that gut Bacteriodetes species are restricted to closely related species of Bacteriodetes fragilis and are abundant in carbohydrate acting enzymes [71]. Lactobacillus species are also known to produce good amounts of β-glucosidase enzyme that help enhance dietary and sensory properties of fermented foods and also play a valuable part in interaction with the host [59]. However studies have shown that excess bioavailability of dietary toxins and xenobiotics is also common due to this enzyme released by LAB [59]. These facts could be taken into consideration to form conditions under which toxicity is prevalent and ways in which the consortium could be altered to tackle poisoning due to amygdalin. This could lead to administration of safer oral doses, after determination of an individual's consortium through faecal studies.

Amygdalin is used as a CAM therapy because, the cyanide obtained on hydrolysis will bind to cytochrome oxidase c and a3, hinder respiration and DNA synthesis due to formation of reactive oxygen species, block nutrition source of cells and lead to lysis [16], [53], [72], [73]. This is useful on parenteral administration but, on ingestion, it reaches the gut unchanged. The gut microbiota is anaerobic and produces high levels of lactic acid via fermentation of pyruvate (anaerobic metabolism) [74]. This pH increases activity of β-glucosidase due to which amygdalin is hydrolysed to cyanide and leads to toxicity. However, R.A. Blaheta et al. have shown that in the absence of β-glucosidase, amygdalin still has anti-tumour properties, giving rise to the possibility that it is not the cyanide that is responsible for that effect [4]. Vitamin C, a water soluble vitamin, is also commonly administered as a CAM therapy for cancer as well as diseases like Epilepsy [93]. It is believed to increase the strength of the intracellular matrix in which cancer cells are embedded, by inhibiting collagenase and hyaluronidase, which weaken the matrix and lead to benign tumors [75], [76]. These two CAM therapies are usually administered together. Now large doses of Vit C are known to deplete cysteine stores of the body. Cysteine plays a role in the rate limiting step of thiocyanate formation [74]. Amygdalin will be hydrolysed by gut microbes, and coupled with the physiological effects of Vitamin C, lead to accelerated cyanide toxicity [77]. Studies by Backer et al., prove the same [78]. Studies have given conflicting results for use of both the therapies alone and in combination. Some suggest it could be due to oral consumption instead of IV that leads to cyanide toxicity instead of rectifying cancer [79]. IV routes lead to low HCN levels, due to absence of β-glucosidase and presence of Rhodanese. Large oral doses are difficult to detoxify due to little or no Rhodanese in the GIT [67].

Diagnosing cyanide poisioning can be difficult and, arterial blood gas analysis could be used for fast and efficient prognosis [80]. After diagnosis, treatment is required for which a cyanide antidote kit was used initially but, it had its own toxicity issues. Now, Cynokit (hydroxocobalamin) is usedand it has no clinically significant adverse effects other than chromaturia and red skin discolouration [81], [82]. Vitamin B12 (cobalamin) can chelate cyanide, due to higher binding affinity, form cyanocobalamin and leave the system through the kidneys [16], [23], [83]. It is used as a cyanide antidote due to this property [53], [84]. It can also be used in combination with thiosulfates like sulfanegen sodium and sodium thiosulfate that can activate the rhodanese pathway of detoxification or α-ketoglutarate that forms cyanohydrin [51], [85], [86], [87], [88]. This combination has been used even to treat cyanide efficacy against cyanide [89]. Another non-conventional therapy could be the consumption of probiotics which is known to decrease levels of Bacteriodetes. However Lactobacillus has been known to produce β-glucosidases. Studies need to be carried out on HCN levels in a cancer patient with low Bacteriodetes and high β-glucosidase producing Lactobascillus on amygdalin ingestion.

6. Conclusion

Several effects of amygdalin and its efficacy have not yet been researched. Those that have been proved with evidence based in-vivo and in-vitro studies are highly controversial, making it dangerous for use as a therapeutic agent. This could be because in-vitro studies lead to direct delivery of the cyanoglycoside while, in-vivo studies do not offer the same. The antibody directed study has paved way for a safer method to deliver amygdalin but, animal and clinical studies are required before therapeutic use. Conflicts also arise due to cases such as that reported by R.A. Blaheta, that document no signs of cyanide toxicity for a patient consuming twice his dose of laetrile tablets. Current literature points to the fact that amygdalin causes toxicity on oral consumption and not IV administration but, its mode of action and toxicity causing dose is still not confirmed. Variable amounts of oral doses cause toxicity in each case and this can be attributed to an eclectic gut consortium. There is no definite way of pointing out each individual's microbial consortium and providing a safe oral dose. Such unproven and conflicting facts make way for a broad avenue of research for a compound that could in-fact be the next step in cancer therapy.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.bbrep.2018.04.008.

Transparency document. Supplementary material

Supplementary material

References

- 1.Cella David F., Tulsky David S., Gray George. The functional assessment of cancer therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. J. Clin. Oncol. 1993;11:570–579. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.3.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Milazzo Stefania, Lejeune Stephane, Ernst Edzard. Laetrile for cancer: a systematic review of the clinical evidence. Support Cancer Care. 2007;15:583–595. doi: 10.1007/s00520-006-0168-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sauer Harald, Wollny Caroline, Oster Isabel. Severe cyanide poisoning from an alternative medicine treatment with amygdalin and apricot kernels in a 4-year-old child. Wien. Med. Wochenschr. 2015;165:185–188. doi: 10.1007/s10354-014-0340-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blaheta Roman A., Nelson Karen, Haferkamp Axel, Juengel Eva. Amygdalin, quackery or cure. Phymedicine. 2016;23(4):367–376. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2016.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gorniak Silvana Lima, Haraguchi Mitsue, Spinosa Helenice de Souza, Nobre Dirceu. Experimental intoxication in rats from a HCN-free extract of Holocalyx glaziovii Taub.: probable participation of the cyanogenic glycoside. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1993;38:85–88. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(93)90082-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shailendra Kapoor. Safety of studies analysing clinical benefit of amygdalin. Immunopharmacol. Immunotoxicol. 2014;36(1):87. doi: 10.3109/08923973.2013.861846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Freier Timothy Alan. Iowa State University; 1991. Isolation and characterization of unique cholesterol-reducinganaerobes (Dissertation) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coates Marie E., Walker R. Interrelationships between the gastrointestinal microflora and non-nutrient components of the diet. Nutr. Res. Rev. 1992;5:85–96. doi: 10.1079/NRR19920008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ravcheev Dmitry A., Godzik Adam, Osterman Andrei L., Dmitry, Rodionov A. Polysaccharides utilization in human gut bacterium Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron: comparative genomics reconstruction of metabolic and regulatory networks. BMC Genom. 2013;14:873. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ge B.Y., Chen H.X., Han F.M., Chen Y. Identification of amygdalin and its major metabolites in rat urine by LC–MS/MS. J of Chrom B. 2007;857 2(1):281–286. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2007.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Manhardt Maria A. Loyola University Chicago; 1981. Correlation of injected amygdalin and urinary thiocyanate in JAX C57 BL/KsJ mice (Dissertation) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sanders Kathleen, Moran Zelda, Shi Zaixing, Paul Rachel, Greenlee Heather. Natural products for cancer prevention: clinical update 2016. Semin. Oncol. Nurs. 2016;32(3):215–240. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2016.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lutz Susan Elizabeth. University of Alberta; 1994. Instrumental and sensory analysis of processed saskatoon berry juice (Dissertation) [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saidu Y. Physicochemical features of rhodanese: a review. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2004;3(4):370–374. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zagrobelny Mika, Bak S.øren, Birger, Møller Lindberg. Cyanogenesis in plants and arthropods. Phytochemistry. 2008;69(7):1457–1468. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2008.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rowe Victoria Ann. Loyola University; 1978. The non-teratogenic effects in mice progeny by maternal treatment with Amygdalin (Dissertation) [Google Scholar]

- 17.David A., Jones Why are so many food plants cyanogenic. Phychemistry. 1998;47:155–162. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(97)00425-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Santamour Frank S., Jr. Amygdalin in Prunus leaves. Phytochemistry. 1998;47(8):1537–1538. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhoua Cunshan, Qianb Lichun, Maa Haile. Enhancement of amygdalin activated with β-d-glucosidase on HepG2 cells proliferation and apoptosis. Carbohydr. Polym. 2012;90:516–523. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2012.05.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chodak Aleksandra Duda, Tarko Tomasz, Satora Paweł., Sroka Paweł. Interaction of dietary compounds, especially polyphenols, with the intestinal microbiota: a review. Eur. J. Nutr. 2015;54:325–341. doi: 10.1007/s00394-015-0852-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tokpohozin Sedjro Emile, Fischer Susann, Sacher Bertram, Becker Thomas. β-D-Glucosidase as “key enzyme” for sorghum cyanogenic glucoside (dhurrin) removal and beer bioflavouring. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2016;97:217–223. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2016.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suchard Jeffrey R., Wallace Kevin L., Richard, Gerkin D. Acute cyanide toxicity caused by apricot kernel ingestion. Ann. Emerg. Med. 1998;32:742–744. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(98)70077-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chan Thomas Y.K. A probable case of Amygdalin-induced peripheral neuropathy in a vegetarian with vitamin B12 deficiency. Ther. Drug Monit. 2006;28:140–141. doi: 10.1097/01.ftd.0000179419.40584.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shraag Thomas A. Cyanide poisoning after bitter almond ingestion. West. J. Med. 1982;136:65–69. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cigolini Davide, Ricci Giogio, Zannoni Massimo. Hydroxocobalamin treatment of acute cyanide poisoning from apricot kernels. Emerg. Med. J. 2011;28(9):804–805. doi: 10.1136/emj.03.2011.3932rep. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jean-Luc Fortin M.D., Stanislas Waroux J.P., Giocanti Hydroxocobalamin for poisioning caused by ingestion of potassium cyanide: a case study. J. Emerg. Med. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2008.04.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Litovitz Toby L., Larkin Robert F., Roy, Myers A.M. Cyanide poisoning treated with hyperbaric oxygen. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 1983;1(27):94–101. doi: 10.1016/0735-6757(83)90041-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hamel Jillian. A review of acute cyanide poisoning with a treatment update. Am. Assoc. Crit.-Care Nurs. 2011;31:72–81. doi: 10.4037/ccn2011799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.N. Walter, Haworth, The Structure of Carbohydrates and of Vitamin C.PA Norstedt, 1937. (Accessed 12 March 2017) 〈http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/chemistry/laureates/1937/haworth-lecture.pdf〉.

- 30.Malcolm L., Brigden Unorthodox therapy and your cancer patient. Postgrad. Med. 1987;81:271–280. doi: 10.1080/00325481.1987.11699682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ogata Kathleen, Volini Marguerite. Mitochondrial rhodanese: membrane-bound and complexed activity. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265(14):8087–8093. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hildebrandt Tatjana M., Grieshaber Manfred K. Three enzymatic activities catalyze the oxidation of sulfide to thiosulfate in mammalian and invertebrate mitochondria. FEBS J. 2008;275:3352–3361. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06482.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mimori Yasuyo, Nakamura Shigenobu, Kameyama Masakuni. Regional and subcellular distribution of cyanide metabolizing enzymes in the central nervous system. J. Neurochem. 1984;43:540–545. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1984.tb00932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Drawbaugh R.B., Marrs T.C. Interspecies differences in rhodanese (thiosulfate sulfurtransferase, EC 2.8.1.1) activity in liver, kidney and plasma. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part B: Comp. Biochem. 1987;86(2):307–310. doi: 10.1016/0305-0491(87)90296-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Okolie Paulinus N., Obasi Bonkens N. Diurnal variation of cyanogenic glucosides, thiocyanate and rhodanese in cassava. Phytochemistry. 1993;33(4):775–778. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sorbo B.H. On the properties of rhodanese- partial purification, inhibitors and intracellular distribution. Acta Chem. Scand. 1951;5:724–734. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nazifia Saeed, Aminlarib Mahmoud, Alaibakhsh Mohammad Ali. Distribution of rhodanese in tissues of goat (Capra hircus) Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part B. 2003;134:515–518. doi: 10.1016/s1096-4959(03)00003-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aminlari M., Vaseghi T., Kargar M.A. The cyanide-metabolizing enzyme rhodanese in different parts of the respiratory systems of sheep and dog. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1994;124(1):67–71. doi: 10.1006/taap.1994.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sorbo B.H. Rhodanese: CN−+S2O3− − → CNS−+SO3− −. Methods Enzymol. 1955;2:334–337. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang Shu-Fang, Volini Margueriti. Studies on the active site of rhodanese. J. Biol. Chem. 1968;243(20):5465–5470. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wood John L., Fiedler Hildegard. β-Mercaptopyruvate: a substrate for rhodanese. J. Biol. Chem. 1953;205:231–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.John, Westley, Rhodanese. In: Advances in Enzymology and Related Areas of Molecular Biology, 39, 11th edn. Wiley, New York, 2009, pp. 327–358.

- 43.Zhang Meiling, Liu Ning, Qian Changli. Phylogenetic and functional analysis of gut microbiota of a fungus-growing higher termite: bacteroidetes from higher termites are a rich source of β-glucosidase genes. Microb. Ecol. 2014;68:416–425. doi: 10.1007/s00248-014-0388-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yun-long Li, Qiao-xing Li, Rui-jiang Liu, Xiang-qian Shen. Chinese medicine Amygdalin and β-glucosidase combined with antibody enzymatic prodrug system as a feasible antitumor therapy. Chin. J. Integr. Med. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s11655-015-2154-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Durmaz G.ökhan, Alpaslan Mehmet. Antioxidant properties of roasted apricot (Prunus armeniaca L.) kernel. Food Chem. 2007;100(3):1177–1181. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sternberg D. β-Glucosidase: microbial production and effect on enzymatic hydrolysis of cellulose. Can. J. Microbiol. 1977;23:139–147. doi: 10.1139/m77-020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Scharf a Michael E., Kovaleva Elena S., Jadhao Sanjay. Functional and translational analyses of a beta-glucosidase gene (glycosyl hydrolase family 1) isolated from the gut of the lower termite Reticulitermes flavipes. Insect. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2010;40:611–620. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mallet A.K. Metabolic activity and enzyme induction in rat Fecal microflora maintained in continuous culture. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1983;46(3):591–595. doi: 10.1128/aem.46.3.591-595.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang Qianfu, Qian Changli, Zhang Xiao-Zhou. Characterization of a novel thermostable β-glucosidase from a metagenomic library of termite gut. Enzyme Microbiol. Technol. 2012;51:319–324. doi: 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2012.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Otieno D.O., Ashton J.F., Shah Nagendra E. Stability of β-glucosidase activity produced by bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus spp. in fermented soymilk during processing and storage. J. Food Sci. 2005;70:M236–M241. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bhattacharya R., Lakshmana Rao P.V., Vijayaraghavan R. In vitro and in vivo attenuation of experimental cyanide poisoning by α-ketoglutarate. Toxicol. Lett. 2002;128:185–195. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4274(02)00012-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vrieze A., Holleman F., Zoetendal E.G., de Vos W.M., Hoekstra J.B.L., Nieuwdorp M. The environment within: how gut microbiota may influence metabolism and body composition. Diabetologia. 2010;53:606–613. doi: 10.1007/s00125-010-1662-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kuugbee Eugene Dogkotenge, Shang Xueqi, Gamallat Yaser. Structural change in microbiota by a probiotic cocktail enhances the gut barrier and reduces cancer via TLR2 signaling in a rat model of colon cancer. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2016;61:2908–2920. doi: 10.1007/s10620-016-4238-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.David M., Greenberg The vitamin fraud in cancer Quackery. West. J. Med. 1975;122:345–348. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Walker W. Allan, Goulet Olivier, Morelli Lorenzo, Antoine Jean-Michel. Progress in the science of probiotics: from cellular microbiology and applied immunology to clinical nutrition. Eur. J. Nutr. 2006;45(Supplement 1):I/1–I/18. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Segata Nicola, Haake Susan Kinder, Mannon Peter. Composition of the adult digestive tract bacterial microbiome based on seven mouth surfaces, tonsils, throat and stool samples. Genome Biol. 2012;13:R42. doi: 10.1186/gb-2012-13-6-r42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Baffoni Loredana, Gaggìa Francesca, Gioia Diana Di, Biavati Bruno. Role of intestinal microbiota in colon cancer prevention. Ann. Microbiol. 2012;62:15–30. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Michlmayr Herbert, Kneifel Wolfgang. β-Glucosidase activities of lactic acid bacteria: mechanisms, impact on fermented food and human health. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2014;352:1–10. doi: 10.1111/1574-6968.12348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Steer Toni E., Johnson Ian T. Metabolism of the soyabean isoflavone glycoside genistin in vitro by human gut bacteria and the effect of prebiotics. Br. J. Nutr. 2003;90:635–642. doi: 10.1079/bjn2003949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sousa Irene Pereira de, Bernkop-Schnürch Andreas. Pre-systemic metabolism of orally administered drugs and strategies to overcome it. J. Control. Rel. 2014;192:301–309. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Berrin Jean-Guy, Czjzek Mirjam. Substrate (aglycone) specificity of human cytosolic β-glucosidase. Biochem. J. 2003;373:41–48. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Daniela Elena Serban Gastrointestinal cancers: influence of gut microbiota, probiotics and prebiotics. Cancer Lett. 2014;345:258–270. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jones Karrie R. Hydroxocobalamin (Cyanokit): a new antidote for cyanide toxicity. Appl. Pharmacol. 2008;30:112–121. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hullar Meredith A.J., Burnett-Hartman Andrea N., Lampe Johanna W. Gut microbes, diet, and cancer. Cancer Treat. Res. 2014;159:377–399. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-38007-5_22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hall Alan H., Rumack Barry H. Hydroxycobalamin/sodium thiosulfate as a cyanide antidote. J. Emerg. Med. 1987;5:115–121. doi: 10.1016/0736-4679(87)90074-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chong Esther Swee Lan. A potential role of probiotics in colorectal cancer prevention: review of possible mechanisms of action. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014;30:351–374. doi: 10.1007/s11274-013-1499-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kleessen Brigitta, Svkura Bernd, Zunft Hans-Joachim. Effects of inulin and lactose on fecal microflora, microbial activity, and bowel habit in elderly constipated persons. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1997;65:1397–1402. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/65.5.1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Herbert Cheuhui Chiang . Washington University; 2009. A hybrid two-component system in bacteroides thetaiotaomicron that regulates nitrogen metabolism (Dissertation) [Google Scholar]

- 69.Patel Seema, Goyal Arun. The current trends and future perspectives of prebiotics research: a review. 3 Biotech. 2012;2:115–125. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Karlsson Fredrik H., Ussery David W., Nielsen Jens, Nookaew Intawat. A closer look at Bacteroides: phylogenetic relationship and genomic implications of a life in the human gut. Microb. Ecol. 2011;61:473–485. doi: 10.1007/s00248-010-9796-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Song Zuoqing, Xu Xiaohong. Advanced research on anti‑tumor effects of amygdalin. J. Can. Res. 2017;10:3–7. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.139743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bhattacharya R., Lakshmana Rao P.V. Pharmacological interventions of cyanide-induced cytotoxicity and DNA damage in isolated rat thymocytes and their protective efficacy in vivo. Toxicol. Lett. 2001;119:59–70. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4274(00)00309-x. (S0378-4274)(00)(00309-X) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bromley Jonathan, Hughes Brett G.M., Leong David C.S. Life-threatening interaction between complementary medicines: cyanide toxicity following ingestion of amygdalin and Vitamin C. Ann. Pharmacol. 2005;39:1566–1569. doi: 10.1345/aph.1E634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Padayatty Sebastian J., Sun Andrew Y., Chen Qi. Vitamin C: intravenous use by complementary and alternative medicine practitioners and adverse effects. PLoS One. 2010;5(7):e11414. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Richards Evelleen. The politics of theraputic evaluation: the vitamin C and cancer controversy. Soc. Stud. Sci. 1988;18(76):653–701. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Edward J., Calabrese Conjoint use of laetrile and megadoses of ascorbic acid in cancer treatment: possible side effects. Med. Hypotheses. 1979;5:995–997. doi: 10.1016/0306-9877(79)90047-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Backer Ronald C., Herbert Victor. Cyanide production from laetrile in the presence of megadoses of ascorbic acid. JAMA. 1979;241(18):1891–1892. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Vickers Dr. Andrew. Alternative Cancer Cures: “unproven” or “Disproven”. CA: Cancer J. Clin. 2004;54:110–118. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.54.2.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Holstege Christopher P. A case of cyanide poisoning and the use of arterial blood gas analysis to direct therapy. Hosp. Pract. 2010;38(4):69–74. doi: 10.3810/hp.2010.11.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Borron Stephen W. Hydroxocobalamin for severe acute cyanide poisoning by ingestion or inhalation. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2007;25:551–558. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2006.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ushakova N.A., Nekrasov R.V., Pravdin I.V. Mechanisms of the effects of probiotics on symbiotic digestion. Biol. Bull. 2015;42(5):394–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Oyewole O.I., Olayinka E.T. Hydroxocobalamin (vit B12a) effectively reduced extent of cyanide poisoning arising from oral amygdalin ingestion in rats. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health Sci. 2009;1:008–011. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Vipperla Kishore, Stephen, O’Keefe J. Intestinal microbes, diet, and colorectal cancer. Curr. Colorectal Cancer Rep. 2013;9:95–105. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tulsawani R.K., Debnath M., Pant S.C. Effect of sub-acute oral cyanide administration in rats: protective efficacy of alpha-ketoglutarate and sodium thiosulfate. Chemico-Biol. Interact. 2005;156:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Brenner Matthew, Kim Jae G., Lee Jangwoen. Sulfanegen sodium treatment in a rabbit model of sub-lethal cyanide toxicity. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2010;248:269–276. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bhattacharya R., Lakshmana Rao P.V., Vijayaraghavan R. In vitro and in vivo attenuation of experimental cyanide poisoning by α-ketoglutarate. Toxicol. Lett. 2002;128:185–195. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4274(02)00012-7. (doi:S0378-4274)(02)(00012-7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hariharakrishnan J., Satpute R.M., Prasad G.B.K.S., Bhattacharya R. Oxidative stress mediated cytotoxicity of cyanide in LLC-MK2 cells and its attenuation by alpha-ketoglutarate and N-acetyl cysteine. Toxicol. Lett. 2009;185:132–141. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2008.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hall Alan H., Dart Richard, Bogdan Gregory. Sodium thiosulfate or hydroxocobalamin for the empiric treatment of cyanide poisoning. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2007;49(6):806–813. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Németh Kitti, Plumb Geoff W., Berrin Jean-Guy. Deglycosylation by small intestinal epithelial cell β-glucosidases is a critical step in the absorption and metabolism of dietary flavonoid glycosides in humans. Eur. J. Nutr. 2003;42:29–42. doi: 10.1007/s00394-003-0397-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Changa Jun, Zhang Yan. Catalytic degradation of amygdalin by extracellular enzymes from Aspergillus niger. Process Biochem. 2012;47:195–200. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Nadir Mary Abou. Texas A&M University; 2012. Directed evolution of cyanide degrading enzymes (Dissertation) [Google Scholar]

- 92.Sawicka-Glazer Edyta, Czuczwar Stanisław J. Vitamin C: a new auxiliary treatment of epilepsy. Pharmacol. Rep. 2014;66:529–533. doi: 10.1016/j.pharep.2014.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.CancerProducts.com Amygdatrile apricot kernel extract (prunus armenicia) PayPal Verified. 2010 〈www.cancerproducts.com/index.html〉 (Accessed 16 April 2017) [Google Scholar]

- 94.Tjsupply.com, Authentic Amygdalin Products. GoDaddy.com Web Server Certificate, 2016. 〈https://www.tjsupply.com/〉.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material