Background

Over the past century, advances in the care of the burned patient have been unprecedented. Mortality has decreased significantly owing to our improved understanding of the pathophysiological response to injury and progress in intensive care, nutrition, surgical techniques and infection control. Subsequently, there has been a paradigm shift from ensuring survival to improving survivorship: that is aiming for an improved quality of life post injury.

Identifying the issues and concerns that matter most to our patients is a difficult process. Changes in healthcare funding have made interactions with patients more time-pressured, with less time available for interactions. In the age of target-driven protocolised pathways, taking an exhaustive history can be difficult. From a patient’s perspective, arranging childcare or leave from work, finding a parking space and then the clinic itself is particularly stressful. Subsequently, they may forget to raise their concerns. For some, the conventional interaction of the outpatient appointment is daunting and patients may feel that they are challenging their care.1 Furthermore, it is often difficult to identify patients that ‘suffer in silence’ and some items, such as sexual relationships, may be potentially embarrassing or difficult for both the patient and healthcare professional to discuss.

Subsequently, patients may have concerns that are either not recognised or not addressed. This occurs despite a wealth of knowledge on the benefits of a patient-centred approach. An open, communicative relationship helps patients understand their health condition, improving satisfaction, improving health outcomes and reducing patient stress.2,3 In summary, a healthcare professional that provides more patient-centred care inspires greater confidence with patients and improved willingness of patients to accept recommendations.3,4

As burn professionals, we continue to pride ourselves that we are better than our other surgical colleagues at providing holistic care. An informal focus group hosted by The Katie Piper Foundation exploring the concerns of burns patients has highlighted the disparity between issues considered important by health professionals managing care and patients receiving care. This has questioned our belief as to whether the patient is indeed at the centre of burn care.

The issue of unmet needs is not a problem unique to burn care; a large trial of cancer patients identified multiple short comings in communication and the assessment of patients’ needs.5 Subsequently, the concept of Holistic Needs Assessment (HNA) has become an integral aspect of current cancer care.6 The National Cancer Survivorship Initiative defines holistic needs assessment (HNA) as ‘a process of gathering information from the patient and/or carer to inform discussion and develop a deeper understanding of what the person understands and needs’ and is concerned with the whole person by incorporating their physical, emotional, spiritual, social, and environmental well-being’.7

The Patient Concerns Inventory (PCI) was born out of some of the shortcomings arising from conventional interactions between healthcare professionals and patients.8 A PCI allows patients to select from a prompt list of carefully chosen potential issues that they may wish to raise during their consultation. It also allows patients to express a preference for input from specified members of the multidisciplinary team. Upon return of the completed PCI checklist, the healthcare professional is able to focus quickly on the issues prioritised by the patient at that time. The PCI provides an opportunity to: encourage patients to talk about what they want to talk about in their clinic encounter; to use a tool that affords that ‘permission’; to de-medicalise the interaction and make it patient-focused; and to make the ‘teachable moment’ more empowering and holistic.

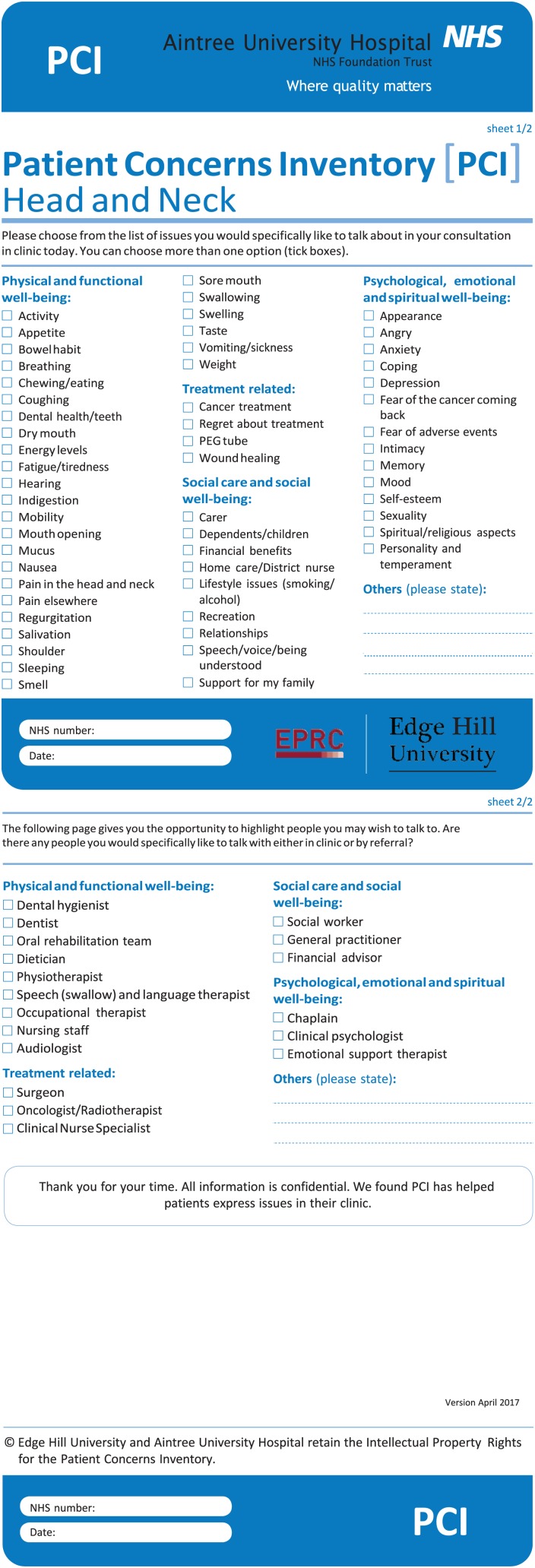

The PCI is now well established in head and neck cancer care (Figure 1) and was included in the 2014 national audit as an indicator of quality of care.9 It has demonstrated validity in identifying patients’ concerns without extending the consultation duration, resulting in greater patient satisfaction. Following its success, the PCI has been developed in rheumatology,10 neuro-oncology11 and breast cancer12 with similar results. The PCI approach has also shown tangible benefits within the financial constraints of healthcare through increased time efficiency, better focus and better deployment of support services.

Figure 1.

Head and neck cancer PCI.8

The progress and successes of PCI in other specialties has laid the foundations for PCI-Burns. As we move forwards with developing a burns patient concerns inventory, we welcome input from and collaboration with everyone in the burn care community to facilitate tailored and collaborative care sensitive to the needs of patients living with the consequences of burns.

References

- 1. Ong LM, de Haes JC, Hoos AM, et al. Doctor-patient communication: a review of the literature. Soc Sci Med 1995; 40(7): 903–918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Greenfield S, Kaplan SH, Ware JE, Jr, et al. Patients’ participation in medical care: effects on blood sugar control and quality of life in diabetes. J Gen Intern Med 1988; 3(5): 448–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Griffin SJ, Kinmonth AL, Veltman MW, et al. Effect on health-related outcomes of interventions to alter the interaction between patients and practitioners: a systematic review of trials. Ann Fam Med 2004; 2(6): 595–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Saha S, Beach MC. The impact of patient-centered communication on patients’ decision making and evaluations of physicians: a randomized study using video vignettes. Patient Educ Couns 2011; 84(3): 386–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Söllner W, DeVries A, Steixner E, et al. How successful are oncologists in identifying patient distress, perceived social support, and need for psychosocial counselling? Br J Cancer 2001; 84(2): 179–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Coulter A, Collins A. Making Shared Decision Making a Reality: No decision about me, without me. London: The King’s Fund, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Henry R, Hartley B, Simpson M, et al. The development and evaluation of a holistic needs assessment and care planning learning package targeted at cancer nurses in the UK. Ecancermedicalscience 2014; 8: 416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rogers SN, El-Sheikha J, Lowe D. The development of a Patients Concerns Inventory (PCI) to help reveal patients concerns in the head and neck clinic. Oral Oncol 2009; 45(7): 555–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Health and Social Care Information Centre. National Head & Neck Cancer Audit 2014, DAHNO Annual Report. 2014. Available at: https://digital.nhs.uk/catalogue/PUB18081 Leeds: Health and Social Care Information Centre. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ahmed A, Rogers S, Bruce H, et al. Development of a rheumatology-specific patient concerns inventory (PCI) and its use in the rheumatology outpatient clinic setting. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2015; 74: 315–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rooney AG, Netten A, McNamara S, et al. Assessment of a brain-tumour-specific Patient Concerns Inventory in the neuro-oncology clinic. Support Care Cancer 2014; 22(4): 1059–1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kanatas A, Lowe D, Velikova G, et al. Issues patients would like to discuss at their review consultation in breast cancer clinics - A cross-sectional survey. Tumori 2014; 100(5): 568–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

How to cite this article

- Gibson JAG, Spencer S, Rogers SN, Shokrollahi K. Formulating a Patient Concerns Inventory specific to adult burns patients: learning from the PCI concept in other specialties. Scars, Burns & Healing, Volume 4, 2018. DOI: 10.1177/2059513117763382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]