Abstract

Introduction:

A burn can have a significant and long-lasting psychosocial impact on a patient and their family. The National Burn Care Standards (2013) recommend psychosocial support should be available in all UK burn services; however, little is known about how it is provided. The current study aimed to explore experiences of psychosocial specialists working in UK burn care, with a focus on the challenges they experience in their role.

Methods:

Semi-structured telephone interviews with eight psychosocial specialists (two psychotherapists and six clinical psychologists) who worked within UK burn care explored their experiences of providing support to patients and their families.

Results and Discussion:

Thematic analysis revealed two main themes: burn service-related experiences and challenges reflected health professionals having little time and resources to support all patients; reduced patient attendance due to them living large distances from service; psychosocial appointments being prioritised below wound-related treatments; and difficulties detecting patient needs with current outcome measures. Therapy-related experiences and challenges outlined the sociocultural and familial factors affecting engagement with support, difficulties treating patients with pre-existing mental health conditions within the burn service and individual differences in the stage at which patients are amenable to support.

Conclusion:

Findings provide an insight into the experiences of psychosocial specialists working in UK burn care and suggest a number of ways in which psychosocial provision in the NHS burn service could be developed.

Keywords: Burn injury, health professionals, psychology, psychosocial adjustment, psychosocial support, qualitative

Lay Summary

Background:

As well as the physical implications of sustaining a burn injury, individuals and their families often face a range of psychological and social difficulties, which can be long-lasting and have a significant impact on their wellbeing. Within UK burn services, health professionals provide psychosocial support for a wide range of difficulties, including anxieties about treatment or social reengagement, depression, coming to terms with appearance chances as a result of scarring, post-traumatic stress and bereavement. However, although psychosocial support is available, little is known about how it is provided. Therefore, the current study aimed to explore the views of health professionals who provide psychosocial support in UK burn care.

Method:

Telephone interviews were carried out with eight health professionals who provide psychosocial support to patients and families affected by burns. The interviews revealed that the health professionals provide a variety of support to individuals and their families, for a wide range of psychological and social issues.

Results:

Analysis identified two key themes: Burn service-related experiences and challenges included health professionals not having enough time to provide support to all patients; patients being unable to attend appointments because they live a large distance from their nearest burn service; patients and families viewing medical appointments as more important than therapy sessions; and difficulties assessing patients with the tools which are currently available. Therapy-related experiences and challenges related to sociocultural and familial factors influencing how patients engage with support, pre-existing mental health difficulties interfering with recovery and a variation in how soon patients feel able to engage with support.

Findings:

The findings provide initial insight into the experiences of psychosocial health professionals in UK burn care and provide directions for future research.

Introduction

Research suggests that the psychosocial impact of a burn may be more difficult to adjust to, and longer-lasting,1 than the physical consequences2–5 such as pain,6,7, itching,7 scarring8 and poor physical function.7–9 Indeed, depression,1,6,8,10–12 anxiety6–8,13 and post-traumatic stress disorder1,6–8,14 are often experienced by patients, in addition to struggles with social situations, for example with friends, romantic partners or at work.6,8,13,15 Many also experience appearance concerns6,7,9,13 which may lead them to avoid activities which draw attention to their scarring (e.g. swimming).6,16 Furthermore, evidence suggests that burn patients have a higher incidence of pre-existing mental health difficulties than the general population, which can lead to prolonged hospital stays and more serious psychiatric problems, post injury.6,8,17,18

The interplay between physical and psychosocial health, which significantly impacts health-related outcomes following a burn,19 makes access to psychosocial support alongside physical care essential. Psychosocial support may be needed in both inpatient and outpatient phases of treatment and, in some cases, for many years following injury.19

At present, the UK’s National Burn Care Standards20 advise that all burn services should include health professionals who are trained to assess, and provide psychosocial support to, patients and their families. A tiered approach is recommended,20,21 whereby all staff receive a level of psychosocial training. Similarly, the European Burns Association (EBA) Practice Guidelines22 recommend that psychologists should be present in burn centres every day of the week. Additionally, they stipulate that psychosocial recovery and adjustment should be a key part of standard clinical care. While these guidelines hold promise, the support actually available within individual services is unknown. To date, just three studies have examined the psychosocial support available to patients following a burn injury;2,23,24 each using surveys to examine support available in Europe and the USA.

In the most recent of these studies, Lawrence et al.2 surveyed 166 health professionals (including surgeons, nurses, psychologists, occupational therapists and physiotherapists) working in hospitals in the UK and USA. The authors examined participants’ perceptions of the psychosocial issues patients experience following a burn and the availability of psychological services. Consistent with other research, the findings identified that many patients were thought to encounter psychosocial difficulties following a burn. Interestingly, psychosocial support was found to be more prevalent in burn care services in the UK than the USA and, positively, 91% of UK health professionals surveyed reported having a psychologist within their burn service. However, the level of psychosocial support available varied between UK burn services; although the reasons for this variation remain unclear. Conducting further qualitative research would enable us to gain rich, nuanced data,25 which may provide a more detailed insight into how support is currently provided within UK burn care services.

In summary, although the importance of access to psychosocial support following a burn injury is widely accepted, the support available seems to vary, and the reasons for this are not well understood. In addition, there has been no qualitative research examining the experiences of health professionals who provide psychosocial support within UK burn care. Having such information may enable us to better understand the challenges of providing psychosocial support to individuals who have sustained a burn injury and give future directions to guide support provision. For this reason, the aim of the current study was to qualitatively explore the experiences of psychosocial specialists working in UK burn services, with a particular focus on their perceptions of challenges or barriers to providing support.

Method

Design

An inductive, qualitative approach was adopted in order to gain an in-depth understanding of a complex and largely understudied area.26

Individual, semi-structured telephone interviews were carried out with psychosocial specialists working in UK NHS burn care services. Interviewees were asked a series of open-ended questions relating to the support they provide to patients with burn injuries and their families, and the challenges they experience in their role.

Participants

Eight psychosocial specialists (seven women), currently working in UK burn care, took part. The sample consisted of psychotherapists (n = 2) and clinical psychologists (n = 6) from six UK burn services, who worked in adult (n = 1), paediatric (n = 4) or mixed age (n = 3) settings. Two worked full-time and six part-time. Pseudonyms are used throughout the results section to maintain participant anonymity.

Procedure

Ethical approval was granted by the NHS and the authors’ university research ethics committee.

Participants were recruited using purposive sampling: emails were sent to members of the British Burn Association (BBA) Psychosocial Special Interest Group (SIG), asking for clinical psychologists, psychotherapists and other psychosocial specialists who were willing to be interviewed about their experiences of providing psychosocial support within UK burn care services.

Interviews were conducted by CG, audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. The duration of interviews was in the range of 32–55 min. Participants were asked a series of open-ended questions relating to psychosocial assessment, the support that they provide to patients with burn injuries and their families, and the challenges that they experience in their role. Interview questions were informed by previous literature in the area.

Data analysis

Surface level thematic analysis was used to analyse the data, following Braun and Clarke’s ‘6 steps of thematic analysis’.25 First, the researcher (EG) became familiar with the data by reading the transcripts multiple times. Next, initial data-driven codes were generated throughout the dataset. The codes were then grouped into broader themes, which were reviewed and further refined; creating larger, over-arching themes. These were then finalised and named, before being used to tell a story with the data.25 The data were also examined by a second researcher (CG) in order to ensure agreement over the themes which emerged. The interviews and analysis were conducted by researchers who had experience of working in this area, and who knew the participants professionally. However, they did not have personal experience of living with a burn injury or of providing psychosocial support to burn patients.

Results and discussion

During the interviews, specialists described the psychosocial support they provided to patients and their families, in relation to many different psychosocial concerns. For burn patients themselves (children, young people and adults), common problems related to anxieties about treatment (e.g. dressing changes, surgery) and concerns about social situations, availability of social support and coming to terms with any changes in their appearance (e.g. scarring, amputation). Interviewees reported providing support for anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder or trauma symptoms relating to the event which led to their burn injury and, in some cases, bereavement. Most participants explained that children, young people and their parents may have specific concerns about returning to nursery or school and that it is not uncommon for new issues to arise as children go through different developmental stages. Romantic relationships were reported as a concern for young people and adults, with some individuals wanting to conceal their burn scars from existing or potential partners. Interviewees spoke of the importance of providing support to the whole family, especially for parents who may experience significant guilt, or blame the other parent for their child’s accident, which may impact seriously on their child’s recovery and the parents’ relationship.

The interviewees reported using a broad range of approaches to support patients and their families. Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) was the most common approach, used by all but one specialist. Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR), person-centred therapy, acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), relaxation, mindfulness, behaviour management, problem-solving and social skills exercises, reassurance, empathy, practical support, peer support and techniques developed by support organisations were also reported.

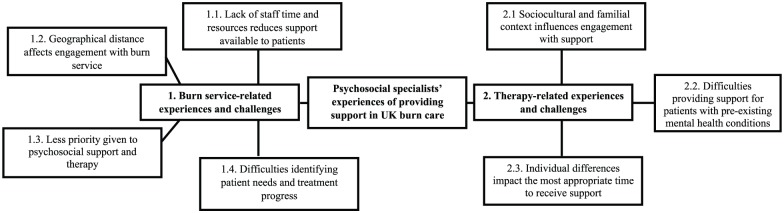

The analysis identified two key themes which related to service-related experiences and challenges, and therapy-related experiences and challenges. The themes and subthemes are visually presented as a thematic map in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Thematic map of themes and related subthemes.

Burn service-related experiences and challenges

This theme outlined the psychosocial specialists’ experiences and the challenges they faced when providing support to burn patients within their service. These were further categorised into four subthemes.

Lack of staff time and resources reduces support available to patients

One major service-related theme, voiced by all participants, was a lack of time and resources, which reduces the number of patients who can access psychosocial support. One interviewee explained, ‘I think that my resource is spread very thinly and sometimes there are situations where I’m not able to physically, in terms of the time I have, to offer the support I’d like to’ (Stephanie). Indeed, of the sample, six reported working part-time, meaning that the support patients receive can be completely dependent upon ‘whether someone comes in on my day of work or not’ (Susan). For this reason, there is a reliance on ‘a lot of indirect consultation with colleagues who are seeing more of them’ (John). Here, psychosocial specialists have to rely on colleagues, who do not have specialist psychosocial training, to gauge which patients require support. For example: ‘the impressions of the clinicians who’ve seen them… if they feel that parents are particularly distressed or if a child is unusually upset either about procedures or the likely consequences of the burn’ (John).

As a consequence, participants described the likelihood that only those who are presenting severe distress will be referred for specialist psychological support: ‘In total, we have 1.1 whole-time equivalent clinical psychology in-put for a service that has over 500 new patients every year, and lots of those young people are followed up for years, so our outpatient caseload of the burns service is massive. So, we can only see those with a more serious identified clinical need’ (Olivia). Additionally, this lack of time prevents minor psychological issues being picked up before they become a chronic problem: ‘they’re always more difficult to help and treat than those where carers or staff at the hospital are vigilant and say “Do you know what, this young person is not coping as well as when we last saw them. Let’s try and get to the bottom of this”’ (Olivia).

These findings are in line with previous research, which has also highlighted that burn services often do not have the capacity to provide psychosocial support to all patients who may benefit from it.27–31 For this reason, health professionals who have not received appropriate psychosocial training may be responsible for assessing psychosocial wellbeing in burn patients.32,33 Wisely et al.32 explain that health professionals who are not psychosocial specialists may be unable to detect all patients’ needs, leading to only those presenting severe distress being referred for psychosocial support and intervention. Consequently, this can lead to psychosocial difficulties being missed, or only being identified at a later stage as more serious, long-term issues because they were not managed in the early stages.

In order to improve patient screening, the National Burn Care Review28 highlighted the need for burn-specific patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) which are sensitive enough to identify burn patients’ needs. This may help to minimise reliance on referrals from other members of staff and increase the effectiveness of psychosocial screening. On a different note, burn-related charities (e.g. Katie Piper Foundation, Children’s Burns Trust and Dan’s Fund for Burns) and burn clubs, which are linked to specific burn services, can also provide social and peer support for individuals and families who are not in need of specialist psychosocial treatment.

Geographical distance affects engagement with burn service

Another prominent physical challenge reported by all the interviewees was the distance many patients travel to receive specialist treatment after leaving hospital. This barrier occurs because ‘being a regional burns unit, we cover a really large area’ (Rachel), therefore ‘if they live far away we might not see them’ (Carol) because the distance is too great to travel for outpatient appointments. Furthermore, a number of specialists mentioned that many patients ‘don’t have their own transport… depend upon public transport’ (Stephanie). This may be particularly difficult for patients with physical injuries which significantly affect their mobility and for patients whose altered appearance attracts unwanted attention in public settings.

A small number of specialists expressed difficulties trying to arrange alternative specialist psychosocial support more locally to deal with patients’ complex needs: ‘there’s hardly any services around’ (Carol); ‘it can be quite specialist therapy and trauma relations therapy’ (Rachel). The reason for this barrier may be that, in the UK, much secondary care has been centralised to a smaller number of regional hospitals. While this benefits patients because they receive specialist care and treatment,34,35 it also means that many patients live a considerable distance from their nearest burn service34,35 or other services that can provide specialist therapy to meet very complex needs.36

On a more positive note, three participants reported overcoming this barrier, somewhat, by using ‘telephone support as well’ (Fiona). One specialist suggested that the use of online therapies could also be useful, ‘particularly with young people, who’re just so used to that kind of way of communicating’ (John). While there are currently no burn-specific online psychosocial interventions, web-based support has been developed for adults and young people who are living with an altered appearance more generally. One such intervention, Face It,37 which uses a combination of CBT and social skills training (approaches that were identified by the interviewees in this study) has been shown to reduce appearance concerns, anxiety and depression, and improve quality of life six months post intervention compared to a control group.38 Such online interventions may be accessible, acceptable and comfortable for burn patients who cannot access face-to-face support or do not feel sufficiently confident to seek it. However, it is important to consider that individuals with low socioeconomic status, who are often most in need of psychosocial support, may be unable to access online resources. Future research should consider whether there is a need for burn-specific online psychosocial support and whether this is a medium which burn patients would be able to access and engage with.

Less priority given to psychosocial support and therapy

Many participants described a belief that patients and other health professionals prioritise attending medical appointments above psychosocial and therapy sessions, which may provide another explanation for non-attendance. One interviewee explained ‘they have so many appointments to attend at the hospital sometimes they view the psychology appointment as a low priority’ (Lily). Similarly, some specialists expressed that many families are ‘just busy doing family things, caring for their young children and, [for] whatever reason, don’t feel able to find the time’ (Fiona) to fit in psychosocial appointments. This may mean that psychosocial difficulties are not picked up early enough to prevent them manifesting into more serious problems which are ‘always more difficult to help and treat’ (Olivia). In addition, the majority of specialists purported that the ‘less psychologically minded’ (Stephanie) patients are difficult to engage with therapy, and often lack insight into their own psychosocial difficulties, which can influence ‘whether someone wants to work with you in a psychological way and try to adjust’ (Susan).

The majority of interviewees felt that access to psychosocial support was restricted because other health professionals were unaware of what was available. For example, one spoke of a patient who ‘initially talked to a member of staff about his concerns and they told him, actually, there was no service’ (Fiona). This suggests a need to raise awareness among the wider multidisciplinary team of the availability of accessible psychosocial support; information ‘needs to be a bit more explicit’ (Fiona).

Few studies have investigated staff perceptions of psychology services within the NHS. However, a National Burn Care Group Report39 suggested that, although psychosocial specialists were perceived as playing a crucial role in supporting both patients and staff members, raising their profile within the wider team was a key priority. Ten years after this report was published, it is apparent that raising the profile of psychosocial specialists within the wider burn team continues to be a priority. These findings highlight the importance of ensuring that the wider multidisciplinary burns team are aware of the psychosocial support available within their unit, and the procedure for signposting patients to this support.

Future qualitative and quantitative research into this area could provide an invaluable insight into current perceptions of psychosocial support in burn care and, if justified, inform strategies to increase patients’ and health professionals’ understanding of a psychosocial specialist’s role within burn care and, ultimately, help to better integrate psychosocial support into routine care. However, it is important to note that increasing awareness of the role of psychosocial specialists in burn care is likely to increase the demand for specialist support which, as identified in a previous theme, is already unable to meet the needs of all patients. Therefore, ways of meeting these increased demands is something which also needs to be given serious consideration.

Difficulties identifying patient needs and treatment progress

Interviewees also talked about how they identified the psychosocial support needs of patients and their families. Many reported that current burn-specific outcome measures are too focused on the wound itself, meaning that it is hard to capture ‘the breadth of the difficulties’ (Susan) experienced following a burn. Specialists expressed the importance of both quality of life (psychosocial) and physical, wound-specific factors when examining patient adjustment: ‘you’re going to miss out the key thing, which is… in a sense the important thing in terms of coping’ (John). Additionally, they felt that it was important to uncover ‘any pre-existing difficulties that might have been around so whether they’re already experiencing mental health problems or if there’s been any bereavements’ (Lily).

Moreover, a number of specialists expressed difficulties finding ‘one questionnaire that captures all difficulties that’s not too long’ (Stephanie) for ‘quite a diverse population’ (Susan). Most did not use psychometric assessments or preferred to use their own ‘existing sort of pack of questionnaires’ (Fiona) in order to measure broader aspects of a burn injury, but they commented that patients ‘don’t like filling in a lot of the standardised (generic) psychometrics for the reason that they don’t feel they’re relevant enough for them’ (Stephanie).

A few specialists reported that the time constraints, outlined above, led staff who are not trained psychosocial specialists to screen patients and make referrals. For example: ‘at the point of submission the nurses screen for psychological vulnerability’ (Olivia). The lack of appropriate burn-specific outcome measures means that referral is often ‘dependent on the staff referring and is based on their own assessment or their own experience of patients’ (Fiona). Therefore, those who need psychosocial support may not always be picked up and referred on. For example, ‘nurses see them and treat the wounds and the scars, they maybe haven’t picked up on particular psychological distress’ (Stephanie).

This supports previous research which has found that, although many outcome measures are used within burn care, very few measure all aspects of burn injuries.13,40–42 Furthermore, asking patients to complete numerous individual measures is impractical and can increase patient burden.42 The UK National Burn Care Review28 recommended the development of burn-specific PROMs to enable health professionals to assess patient needs, and measure physical and psychosocial change as a result of treatment.40 Using tried and tested PROMs to screen for psychosocial need, rather than relying on the judgement of non-specialist staff, could reduce instances where patients are not referred for support because signs of difficulty have been overlooked and increase the likelihood they will be offered the support they need. Using PROMs will also ensure consistent measurement of psychosocial adjustment between burn services and reliably demonstrate treatment outcomes.

Positively, a number of burn-specific PROMs, to assess age-specific physical and psychosocial wellbeing following a burn injury, are currently being developed. For example, the Brisbane Burn Scar Impact Profile (BBSIP) has been developed in Australia43 and the CARe Burn Scales (www.careburnscales.org.uk) have been developed in collaboration with UK burn patients. As well as identifying those who may benefit from further psychosocial support, these measures allow health professionals to track therapeutic progress and will be less burdensome for patients than an amalgamation of generic outcome measures. New ways of administering and scoring PROMs using electronic devices44 may reduce the demands on staff and hospital resources so that patients’ outcomes can be assessed and monitored more easily.

Therapy-related experiences and challenges

This theme related to clinicians’ experiences when providing therapy for individuals who have had a burn injury. Three sub-themes were identified.

Sociocultural and familial context influences engagement with support

Several participants described a number of sociocultural issues which they believed could influence patients’ engagement with therapy and adjustment to their burn. First, parents’ beliefs about beauty were thought to influence a child’s ability to accept and adjust to any appearance changes. For example, one specialist recounted a case where ‘the child had to lose her leg from the burn and they would’ve preferred her to die because they said “she’ll never be able to get married”’ (Carol). In such a situation, Carol explained that ‘you have to keep working with them [child] ‘til they’re adult enough to have their own view’ and help them understand that ‘images aren’t everything and a scar makes you unique or individual’.

The burns and wider visible difference literature45,46 echoes these findings, indicating the importance and influence of core beliefs about appearance-altering conditions; for example, that scarring is a punishment from God or will prevent an individual from leading a successful life.46 This highlights the importance of identifying patients’ own beliefs (and those of their parents, when working with children and young people) to ensure that these are incorporated into therapy to increase the likelihood of the best psychosocial outcomes.45,46

In addition to this, several specialists reported language barriers making it difficult to engage patients in therapy and outcome assessment: ‘obstacles of language is a very big one – we have a lot of people who don’t speak English – it’s a huge obstacle and we have an interpreting service, but it’s very expensive so we’re encouraged to use it as little as possible. But we do still use it, either on the phone, which is not great, or having someone come in, and we do that regularly but it’s still not great’ (Carol).

Given that the UK is a multi-cultural society with many non-English speakers, communication barriers are a prevalent issue within the NHS.47 Although this issue has not been researched in relation to burn care, it is detailed within much nursing literature (e.g. Gerrish et al.47 and Bischoff et al.48). Additionally, a small number of studies36,49 have highlighted the difficulty for non-English speaking patients to engage with psychosocial support. This may be especially problematic because many units are unable to use interpreter services due to their high cost.48 Again, this suggests that the availability of resources may impede the provision of psychosocial support to people with burn injuries and their families. Subsequently, there is often a reliance on family members to translate information,48 which can hinder engagement with services. Due to the cost of interpreter services, alternative provisions to accommodate non-English speaking patients should be investigated in order to ensure that these patients are able to access appropriate support following a burn injury.

Difficulties providing support for patients with pre-existing mental health conditions

Participants also spoke of a high prevalence of pre-existing mental health problems: ‘we have a lot of mental health patients’ (Carol). Many commented on the complexity of burn patients, often ‘coming from fairly chaotic backgrounds and life circumstances and I think that can make it harder for some people to engage in therapy’ (Susan).

Interviewees also felt that ‘the additional mental health problems on top [of burns-related issues], so things like psychosis, personality disorders, chronic depression’ (Susan), which are commonly associated with the cause of their burn injury, mean their psychosocial needs differ from the rest of the burns population, and they may therefore be best suited to ‘more of a psychiatric pathway’ (Susan). However, participants also reported difficulties gaining support from patients’ local mental health services: ‘they’re usually far away, we don’t usually manage to get them to come except a local person maybe for an assessment or something’ (Carol). This, again, illustrates barriers to support which may be caused by the distance between patients’ homes and their nearest burn service.

The prevalence of pre-existing mental health difficulties is well documented in previous research,6,8,17,18,50,51 and evidence suggests that pre-morbid mental health conditions (e.g. depression, schizophrenia and generalised anxiety disorder)51 are related to greater burn total body surface area (TBSA)51 and poorer psychosocial and general functioning at three months following initial injury.50 Additionally, for these patients, cause of injury may be linked to symptoms of their pre-existing mental health condition(s) (e.g. due to confusion, carelessness, intoxication or self-harm).50 For this reason, the complex psychiatric needs of these patients may be best treated within the mental health service.33 However, participants in the current study reported it being difficult to involve patients’ local mental health services in their care. In line with this, Tarrier et al.50 describe associated ‘placement problems’, whereby there is no optimum place for burn patients with pre-morbid psychiatric problems to receive treatment. Consequently, because their needs are not fully met, they may remain in hospital for a prolonged period of time.50 This illustrates the need for specific treatment pathways for patients with pre-existing mental health difficulties.

Individual differences impact the most appropriate time to receive support

The point at which patients feel comfortable accepting psychosocial support, or whether they are ready to engage with it, was said to differ greatly between individuals. For example, ‘Some people want help initially before they can actually get on with their treatment, even as an inpatient, and some people want to get their treatment done or going strong before they can even think about the psychological side’ (Carol).

Similarly, four interviewees who worked in paediatric services reported how the possible delayed impact of a burn injury posed a challenge that may warrant support: ‘a child can be ticking along and a developmental stage can happen and bring things up again for them’ (Rachel). For example: ‘a child might be injured at a very young age; as a toddler, and not have any difficulties at all until they maybe reach adolescence, and then become more vulnerable to these types of concerns, and that can affect their relationships and social interactions with other people’ (Lily). These new issues were reported to often occur when a child has a ‘change of school or moving into adolescence, perhaps when they’re starting to think about more intimate relationships, [or] changing peer groups’ (Olivia). Therefore, unless a patient is regularly followed up and assessed by the burns service over their lifespan, there is a risk that these concerns may be missed. In addition, individuals may not know that they can, or not feel able to, contact their burn service if they are struggling at a later date.

Consistent with these findings, the National Burn Care Review28 stipulates that long-term psychosocial care should be available to patients, especially in the case of children, who should be assessed throughout their development into adulthood. However, patients may find it difficult to re-engage with their burn service after they have stopped receiving treatment,2 and those who were initially treated in a paediatric service, and later encounter new concerns during adulthood, may struggle to transition to a completely different service or may be unaware that support is available to them.

Although follow-up is not standardised in UK burn care, the BBA recommends core outcome measures be administered every six months from the point of wound healing and, while the patient remains under care, annually from the point of discharge from the scar management service.52 Collecting regular, long-term outcome data from patients will enable health professionals to identify changes in patient needs over time and offer support when it may be beneficial.

The UK’s Northern Burn Care Network has developed a website for young people in the North of England (www.hello-again.co.uk), offering information about transitioning to adult services, links to relevant information and support, and personal stories from young people who have previously made this transition. Online materials, such as these, may help to inform individuals about where they can gain support after leaving the paediatric service and give them confidence to access it. Detailed guidelines from the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE)53 cover the transition pathway from child to adult health or social care services. Employing clear guidelines in UK burn care may enable patients to benefit from follow-up care for a duration which suits their individual needs.

Conclusion

This qualitative study has given an insight into psychosocial specialists’ experiences of providing support within UK burn care services. It identifies a number of inter-related challenges, many of which point towards under-resourcing, a reliance on the judgement of staff who have not received specialist psychosocial training and difficulty accessing local burn-specific psychosocial support after discharge from hospital. Patients and other staff were thought to not always be aware of the psychosocial support that was available and to prioritise medical over psychosocial outpatient appointments. Other factors, including language barriers and pre-existing mental health conditions, were also thought to make it difficult for some patients to engage with therapy or support. Finally, interviewees described how individual differences regarding the time at which patients were amenable to psychosocial support meant that some found it difficult to re-engage with the service when they could benefit from it.

These results may usefully guide the future support available to burn patients in the UK and beyond. For instance, increased investment in psychosocial specialists could mean that the needs of a greater number of burn patients are identified and appropriate psychosocial support is available. There may also be potential benefits of establishing efficient, cost-effective means of assessing patient needs, for example by using online burn-specific PROMs. Greater use of online psychosocial interventions may be an option for increasing access to timely support for individuals who, for any reason, find it difficult to access face-to-face services at their burn service, or re-engage with the service following discharge. Finally, establishing specific treatment pathways for individuals with pre-existing mental health problems may allow them to receive the most appropriate support and reduce their time in hospital.

Although this study relies on a relatively small sample, the participants were from a range of services across the UK and had experience working with a mixture of patient groups. Additionally, the sample size is deemed appropriate for an in-depth, exploratory qualitative interview study.54 Moreover, it provides insight into an important and understudied area; namely, the experiences of specialists looking to provide psychosocial care in UK burn services. Future service developments and research should examine the issues raised in detail and consider ways to overcome these barriers so that patients receive the psychosocial support they need after a burn injury.

Acknowledgments

This study was conducted as part of a program of research funded by Restore Burn and Wound Research, together with The Children’s Burns Research Centre and Dan’s Fund for Burns. The Children’s Burns Research Centre, part of the Burns Collective, is a Scar Free Foundation initiative.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The publication of this research was funded by the Katie Piper Foundation.

References

- 1. Willebrand M, Andersson G, Ekselius L. Prediction of psychological health after an accidental burn. J Trauma 2004; 57: 367–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lawrence JW, Qadri A, Cadogan J, et al. A survey of burn professionals regarding the mental health services available to burn survivors in the United States and United Kingdom. Burns 2016; 42: 745–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Partridge J, Robinson E. Psychological and social aspects of burns. Burns 1995; 21: 453–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Phillips C, Fussell A, Rumsey N. Considerations for psychosocial support following burn injury—a family perspective. Burns 2007; 33: 986–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Park S-Y, Choi K-A, Jang Y-C, et al. The risk factors of psychosocial problems for burn patients. Burns 2008; 34: 24–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Patterson DR, Everett JJ, Bombardier CH, et al. Psychological effects of severe burn injuries. Psychol Bull 1993; 113: 362–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wiechman SA, Patterson DR. Psychosocial aspects of burn injuries. BMJ 2004; 329: 391–393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Anderson NJ, Bonauto DK, Adams D. Psychiatric diagnoses after hospitalization with work-related burn injuries in Washington State. J Burn Care Res 2011; 32: 369–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Thombs BD, Haines JM, Bresnick MG, et al. Depression in burn reconstruction patients: symptom prevalence and association with body image dissatisfaction and physical function. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2007; 29: 14–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lawrence JW, Fauerbach JA, Thombs BD. Frequency and correlates of depression symptoms among long-term adult burn survivors. Rehabilitation Psychology 2006; 51: 306. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Van Loey NE, Van Son MJ. Psychopathology and psychological problems in patients with burn scars. Am J Clin Dermatol 2003; 4: 245–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wiechman SA, Ptacek J, Patterson DR, et al. Rates, trends, and severity of depression after burn injuries. J Burn Care Rehabil 2001; 22: 417–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lawrence JW, Mason ST, Schomer K, et al. Epidemiology and impact of scarring after burn injury: a systematic review of the literature. J Burn Care Res 2012; 33: 136–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Baur K, Hardy P, Van Dorsten B. Posttraumatic stress disorder in burn populations: a critical review of the literature. J Burn Care Rehabil 1998; 19: 230–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pallua N, Künsebeck H, Noah E. Psychosocial adjustments 5 years after burn injury. Burns 2003; 29: 143–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Andreasen N, Norris A. Long-term adjustment and adaptation mechanisms in severely burned adults. J Nerv Men Dis 1972; 154: 352–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kolman PB. The incidence of psychopathology in burned adult patients: a critical review. J Burn Care Rehabil 1983; 4: 430–436. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Berry CC, Wachtel TL, Frank HA. An analysis of factors which predict mortality in hospitalized burn patients. Burns 1982; 9: 38–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pavoni V, Gianesello L, Paparella L, et al. Outcome predictors and quality of life of severe burn patients admitted to intensive care unit. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 2010; 18: 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. National Network for Burn Care. National Burn Care Standards. London: BBA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Shepherd L, Tew V, Rai L. A comparison of two psychological screening methods currently used for inpatients in a UK burns service. Burns 2017; 43: 1802–1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. European Burns Association. European Practice Guidelines for Burn Care. Hertogenbosch: EBA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Holaday M, Yarbrough A. Results of a hospital survey to determine the extent and type of psychologic services offered to patients with severe burns. J Burn Care Rehabil 1996; 17: 280–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Van Loey N, Faber A, Taal L. A European hospital survey to determine the extent of psychological services offered to patients with severe burns. Burns 2001; 27: 23–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006; 3: 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Morse J, Richards L. Read me first for a user’s guide to qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kleve L, Robinson E. A survey of psychological need amongst adult burn-injured patients. Burns 1999; 25: 575–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. National Burn Care Review. Committee Report: Standards and Strategy for Burn Care: A Review of Burn Care in the British Isles. London: BBA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wisely J, Tarrier N. A survey of the need for psychological input in a follow-up service for adult burn-injured patients. Burns 2001; 27: 801–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shakespeare V. Effect of small burn injury on physical, social and psychological health at 3–4 months after discharge. Burns 1998; 24: 739–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Heath J, Williamson H, Williams L, et al. Patient-perceived isolation and barriers to psychosocial support: A qualitative study to investigate how peer support might help parents of burn-injured children. Scars, Burns & Healing 2018; 4: 1–12. DOI: 10.1177/2059513118763801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wisely JA, Hoyle E, Tarrier N, et al. Where to start? Attempting to meet the psychological needs of burned patients. Burns 2007; 33: 736–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Clarke A, Cooper C. Psychosocial rehabilitation after disfiguring injury or disease: investigating the training needs of specialist nurses. J Adv Nurs 2001; 34: 18–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Dusheiko M, Halls P, Richards W. The effect of travel distance on patient non-attendance at hospital outpatient appointment: A comparison of straight line and road distance measures. In: Fairbairn D, (ed.) GISRUK 2009: Proceedings of the GIS Research UK 17th Annual Conference; 2009. April 1–3; Durham, UK: University of Durham; 2009, pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jo M. The reconfiguration of hospital services in England. London: Kings Fund, 2007. Available at: http://wwwkingsfundorguk/publications/briefings/the_1html (last accessed on 29th February 2008). [Google Scholar]

- 36. Alavi N, Hirji A, Sutton C, et al. Online CBT is effective in overcoming cultural and language barriers in patients with depression. J Psychiatr Pract 2016; 22: 2–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bessell A, Clarke A, Harcourt D, et al. Incorporating user perspectives in the design of an online intervention tool for people with visible differences: Face IT. Behav Cogn Psychother 2010; 38: 577–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Williamson H, Hamlet C, White P, et al. Study protocol of the YP Face IT feasibility study: comparing an online psychosocial intervention versus treatment as usual for adolescents distressed by appearance-altering conditions/injuries. BMJ Open 2016; 6: e012423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Persson M, Rumsey N, Spalding H, et al. Bridging the gap between current care provision and the psychological standards of burn care: Staff perceptions of current psychosocial care provision and their views of the way forwards. London: BBA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Griffiths C, Guest E, White P, et al. A systematic review of patient-reported outcome measures used in adult burn research. J Burn Care Res 2017; 38: e521–e545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Griffiths C, Armstrong-James L, White P, et al. A systematic review of patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) used in child and adolescent burn research. Burns 2015; 41: 212–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Shepherd L, Tew V, Rai L. A comparison of two psychological screening methods currently used for inpatients in a UK burns service. Burns 2017; 43: 1802–1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tyack Z, Ziviani J, Kimble R, et al. Measuring the impact of burn scarring on health-related quality of life: development and preliminary content validation of the Brisbane Burn Scar Impact Profile (BBSIP) for children and adults. Burns 2015; 41: 1405–1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Griffiths C. PROMs: putting cosmetic patients at the forefront of evaluation. Journal of Aesthetic Nursing 2014; 3: 495–497. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hughes J, Naqvi H, Saul K, et al. South Asian community views about individuals with a disfigurement. Diversity in Health & Care 2009; 6: 241–253. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Naqvi H, Saul K. Culture and ethnicity. In: Oxford Handbook of the Psychology of Appearance. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012, pp. 203. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Gerrish K, Chau R, Sobowale A, et al. Bridging the language barrier: the use of interpreters in primary care nursing. Health Soc Care Community 2004; 12: 407–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Bischoff A, Bovier PA, Isah R, et al. Language barriers between nurses and asylum seekers: their impact on symptom reporting and referral. Soc Sci Med 2003; 57: 503–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Shafran R, Clark D, Fairburn C, et al. Mind the gap: Improving the dissemination of CBT. Behav Res Ther 2009; 47: 902–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Tarrier N, Gregg L, Edwards J, et al. The influence of pre-existing psychiatric illness on recovery in burn injury patients: the impact of psychosis and depression. Burns 2005; 31: 45–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Hudson A, Al Youha S, Samargandi OA, et al. Pre-existing psychiatric disorder in the burn patient is associated with worse outcomes. Burns 2017; 43: 973–982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. British Burn Association. Outcome Measures for Adult & Paediatric Services. London: BBA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 53. NICE. Transition from children’s to adults’ services for young people using health or social care services. London: NICE, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How many interviews are enough? Field Methods 2006; 18: 59–82. [Google Scholar]

How to cite this article

- Guest E, Griffiths C, Harcourt D. A qualitative exploration of psychosocial specialists’ experiences of providing support in UK burn care services. Scars, Burns & Healing, Volume 4, 2018. DOI: 10.1177/2059513118764881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]