Abstract

Objective

To examine the association between an umbilical artery notch and fetal deterioration in monochorionic/monoamniotic (MC/MA) twins.

Methods

Six MC/MA twin pregnancies were admitted at 24–28 weeks of gestation for close fetal surveillance until elective delivery at 32 weeks or earlier in the presence of signs of fetal deterioration. Ultrasound (US) examinations were performed twice weekly. The presence of cord entanglement, umbilical artery notch, abnormal Doppler parameters, a non-reassuring fetal heart rate pattern, or an abnormal fetal biophysical profile was evaluated.

Results

Umbilical cord entanglement was observed on US in all pregnancies. The presence of an umbilical artery notch was noted in four out of six pregnancies and in two of them an umbilical artery notch was seen in both twins. The umbilical artery pulsatility index was normal in all fetuses. Doppler parameters of the middle cerebral artery and ductus venosus, fetal biophysical profile and fetal heart rate monitoring remained normal until delivery in all pregnancies. All neonates experienced morbidity related to prematurity; however, all were discharged home in good condition.

Conclusion

The presence of an umbilical artery notch and cord entanglement, without other signs of fetal deterioration, is not indicative of an adverse perinatal outcome.

Keywords: cord entanglement, Doppler velocimetry, fetal hypoxia, fetal surveillance, umbilical cord knot

Introduction

Monochorionic/monoamniotic (MC/MA) twin gestations are infrequent, with a prevalence of 1 in 8,000 pregnancies [1, 2], and at risk of complications related to monochorionicity [3–5], such as twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome [6, 7], twin-reversed arterial perfusion [8,9], fetal growth restriction [10–12], congenital anomalies [13], and preterm delivery [14–16]. In addition, MC/MA pregnancies may be affected by unique complications, such as conjoined twins [17], and umbilical cord entanglement that can increase the risk of fetal death [18, 19]. Kofinas et al. [20] first reported the presence of an umbilical artery notch associated with cord entanglement in a triplet pregnancy with MC/MA twins. One of the twins died in utero and the co-twin had a non-reassuring fetal heart rate pattern requiring an emergency cesarean delivery [20]. Therefore, the presence of an umbilical artery notch in the setting of MC/MA twins has been considered a poor prognosis sign, but has seldom been reported [20–22].

In MC/MA twin gestations, it is important to identify the presence of cord entanglement and signs of fetal deterioration, such as abnormal Doppler velocimetry and non-reassuring fetal heart rate patterns [23–25]. The prevalence of cord entanglement can reach 70–80% in all MC/MA pregnancies [26], yet most will have a favorable outcome [27]. In addition, Hugon-Rodin et al. [22] and Abuhamad et al. [21] have reported favorable outcomes in MC/MA twin gestations when an umbilical artery notch is present; however, further observations are desirable. In this study, we aimed to examine the association between an umbilical artery notch and signs of fetal deterioration in MC/MA twin pregnancies.

Study Population

From 2007 to 2013, 53 MC twin pregnancies were evaluated; nine of them (17%) were MA: one was a conjoined twin pregnancy, two presented early deliveries, and six MC/MA twin pregnancies without evidence of congenital anomalies were followed longitudinally. All pregnant women were enrolled in research protocols approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and by the Human Investigation Committee of Wayne State University, and provided written informed consent for ultrasound (US) examination.

The pregnant women were admitted at 24–28 weeks of gestation for close fetal monitoring until delivery. US examinations were performed twice weekly in all pregnancies. Daily fetal heart rate monitoring and fetal biophysical profile evaluations were also conducted. All sets of twins were electively delivered by cesarean section at 32 weeks of gestation or earlier in presence of signs of fetal deterioration. Before delivery, all pregnant women received a course of steroids to accelerate lung maturity (12 mg betamethasone/2 doses, 24 h apart).

US Examination

Evaluation of fetal anatomy and weight was performed in all fetuses. In all pregnancies, signs of twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome, consisting of discrepancy in the size of the bladders and in the amount of amniotic fluid, and abnormal Doppler parameters of the umbilical artery and ductus venosus (absent diastolic flow and absent atrial flow, respectively) were investigated [28, 29]. The presence/absence of cord entanglement was documented by visualization of the umbilical cords from the fetal abdomen to the placental insertion site. If present, the location of the cord entanglement (either close to the placenta or to one of the fetuses) was registered. Doppler recordings of the umbilical artery were obtained for each twin at three locations: (1) close to the entrance into the fetal abdomen, (2) at a free loop of the umbilical cord, and (3) near the cord entanglement. In addition, a Doppler evaluation of the umbilical arteries within the cord entanglement was performed. An umbilical artery notch was defined as a discontinuous trace in the late systolic phase of the waveform (Figure 1A). The pulsatility index [PI, (peak systolic velocity – end-diastolic velocity)/mean maximum average velocity; normal: <95th centile for gestational age [30] ] and characteristics of the diastolic flow in the umbilical artery, middle cerebral artery and ductus venosus were also evaluated in both twins.

Figure 1.

Changes in the shape of the umbilical artery notch recorded at different locations: a close to the fetal abdominal insertion of the umbilical cord, b close to the site of cord entanglement, c within the cord entanglement, and d high-definition color flow Doppler using three-dimensional US of the umbilical cord entanglement.

Healthcare providers were informed of the presence of cord entanglement and/or umbilical artery notching. In one pregnancy, the decision to deliver at 28 weeks of gestation was based only on the presence of cord entanglement without other signs of fetal deterioration. In the other five pregnancies, there were no fetal Doppler abnormalities or abnormal fetal heart tracings, and the twins were delivered at 32 weeks of gestation. Neonatal outcomes along with pathology examination of the placenta and umbilical cord were registered.

Results

Descriptive characteristics of the six pregnancies are presented in Table 1. Intrauterine growth restriction was diagnosed in two pregnancies, with both twins affected in one of them. Cord entanglement was observed in all six pregnancies, and in four pregnancies it was located close to the placental insertion of the cords. An umbilical artery notch was visualized in four out of six pregnancies, and in two of them an umbilical notch was noted in both twins. The presence of a notch did not affect the PI or the diastolic flow velocities in the umbilical artery of any fetus. In all four pregnancies, the location of the notch within the umbilical cord changed from one examination to another and was more frequently observed close to the cord entanglement (Figure 1A, 1B). When the umbilical was examined within the cord entanglement, a dynamic change in the Doppler waveform was observed with intermittent presence of an umbilical artery notch, but with normal diastolic flow (Figure 1C). Doppler velocimetry of the middle cerebral artery and ductus venosus, fetal heart rate monitoring, and the fetal biophysical profile all remained within normal limits until delivery.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of six MC/MA twin pregnancies with an umbilical artery notch

| Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 4 | Patient 5 | Patient 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age (years) | 23 | 29 | 28 | 23 | 17 | 28 |

| Gestational age at hospitalization (weeks) | 24 | 26 | 24 | 26 | 28 | 27 |

| Gestational age at delivery (weeks+days) | 28+5 | 32+0 | 32+1 | 32+0 | 32+2 | 32+2 |

| Birthweight (g) (Twin A, Twin B) | 1190 / 1300 | 1745 / 1685 | 1950 / 1895 | 1485 / 1320 | 2000 / 1870 | 1675 / 1730 |

| APGAR at 1and 5 minutes (Twin A, Twin B) | 6/8 7/8 | 8/9 8/8 | 7/8 6/8 | 3/8 6/7 | 3/6 4/8 | 6/8 5/7 |

| Cord pH (Twin A, Twin B) | 7.2/7.2 | 7.3/7.2 | 7.3/7.3 | 7.3/7.2 | 7.2/7.3 | 7.3/7.3 |

| Ultrasound findings | Cord entanglement Umbilical artery notch in both twins |

Cord entanglement No umbilical artery notch |

Cord entanglement No umbilical artery notch |

Cord entanglement Umbilical artery notch in one twin |

Cord entanglement Umbilical artery notch in one twin |

Cord entanglement Umbilical artery notch in both twins |

| Placenta and umbilical cord pathology examination | Cord entanglement Marginal placental insertion of the two cords |

Cord entanglement Close placental insertion of the umbilical cords |

Cord entanglement Close placental insertion of the umbilical cords |

Cord entanglement Close placental insertion of the umbilical cords |

Cord entanglement Forked placental cord insertion Cord knot |

Cord entanglement Cord knot |

| Neonatal complications | ||||||

| Twin 1 | RDS Hyperbilirubinemia |

IVH grade I Hypoglycemia Hyperbilirubinemia |

IVH grade 1 RDS Hyperbilirubinemia |

IVH grade I, RDS | RDS | RDS Hyperbilirubinemia |

| Twin 2 | RDS Hyperbilirubinemia |

TTN, Bradychardia Anemia, | TTN Hyperbilirubinemia |

IVH Grade I, RDS Bradycardia Anemia |

RDS | RDS Hyperbilirubinemia |

RDS, respiratory distress syndrome; TTN, transient tachypnea of the newborn; IVH, intraventricular hemorrhage.

Characteristics of the neonates and pathology examinations of the placenta/umbilical cord are shown in Table 1. One pregnant woman had a cesarean delivery at 28 weeks and 5 days of gestation due to cord entanglement and an umbilical artery notch without other signs of fetal deterioration or the presence of additional pregnancy complications. All other sets of twins were electively delivered at 32 weeks of gestation. Umbilical cord pH values were normal (≥ 7.20) in all newborns; three newborns had a 1-min Apgar score of ≤ 4, but recovered at 5 min; 10 newborns (83%) presented with mild to severe respiratory complications at birth, from transient tachypnea (n = 2) to respiratory distress syndrome (RDS; n = 9); 7 neonates (58%) had hyperbilirubinemia, and 4 (33%) developed an intraventricular hemorrhage grade I. There were no neonatal deaths, and all neonates were discharged home in good condition.

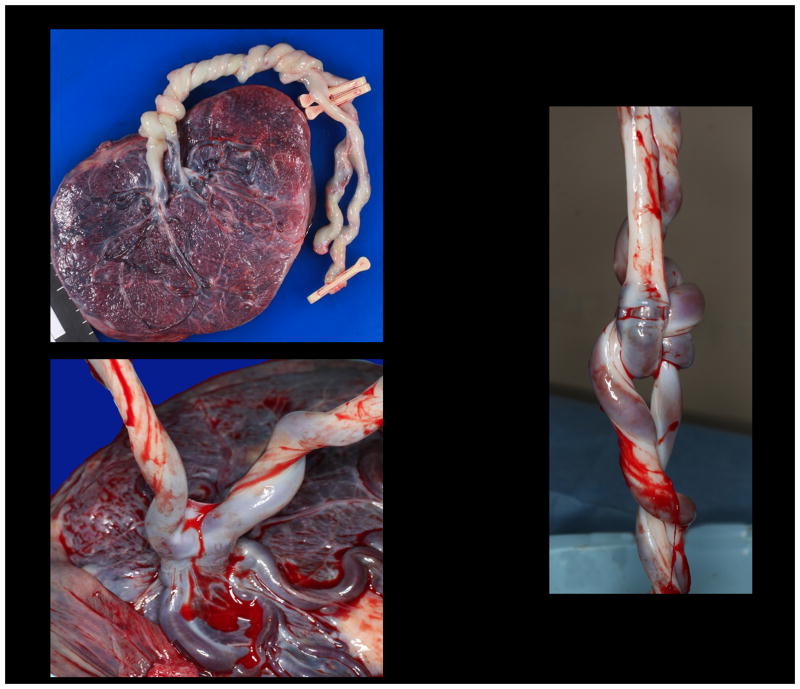

Cord entanglement was confirmed at the time of birth in all pregnancies (Figure 2A), an umbilical cord knot was observed in two pregnancies (Figure 2A, 2B), a forked placental insertion of the umbilical cords in one set of twins (Figure 2C), and a marginal placental insertion of the cords for the other set of twins. In three cases, the placental insertions of the umbilical cords were observed at approximately 1–2 cm to one another.

Figure 2.

Gross examination of the umbilical findings after birth: a entanglement of the umbilical cords with a true knot, b umbilical cord knot, and c forked placental insertion of the umbilical cords of both twins.

Discussion

The main findings of this study are: (1) umbilical cord entanglement was observed in all six studied pregnancies; (2) an umbilical artery notch was observed in four pregnancies and in two pregnancies a notch was noted in both twins; (3) umbilical artery notching was more commonly observed close to the cord entanglement; however, in repeated examinations the notch changed its location in the umbilical cord and its shape; (4) the PI and diastolic velocities in the umbilical artery remained normal; and (5) no signs of fetal deterioration were documented in any case.

Clinical Significance of an Umbilical Artery Notch

Notching of the umbilical artery usually affects the late systolic [21] or early diastolic phase [20] of the Doppler waveform and has been proposed to result from narrowing, distortion or compression of the umbilical vessels [31, 32]. In singleton pregnancies, an umbilical artery notch has been associated with an abnormal insertion of the umbilical cord [21, 32], a tight umbilical cord knot [33], fetal intra-abdominal umbilical vein dilatation [34], and gastroschisis [35]. Abuhamad et al. [36] proposed that the presence of an umbilical artery notch in singleton gestations should prompt targeted US examination to search for anomalies in the umbilical cord and in the placenta as well as increased fetal surveillance due to the risk of non-reassuring fetal heart rate pattern.

In MC/MA twins, an umbilical artery notch has been associated with cord entanglement and adverse perinatal outcome [20, 33]. Table 2 summarizes the findings and obstetrical outcome of previous studies reporting of notching in the umbilical artery waveform in MC/MA twin gestations [20–22]. All were reported in the third trimester and 3 out of 4 had a favorable perinatal outcome. In our cases, we were able to observe an umbilical artery notch in four pregnancies, with the location of the notch changing, but more apparent close to the cord entanglement. Mechanical factors that stretch the cord, such as entanglement, true knots and fetal movements, can increase the tension in the arterial wall of the umbilical artery, thus contributing to umbilical artery notching.

Table 2.

Previous studies reporting an umbilical artery notch in monochorionic/monoamniotic twin gestations

| Author | GA at detection (weeks) | Cord entanglement (US or pathology) | Clinical characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kofinas et al.(20) | 32 | Yes | Fetal demise of one twin at time of ultrasound, an umbilical artery notch was observed in the surviving twin Nonreactive non-stress test, abnormal fetal biophysical profile, abnormal umbilical artery Doppler. Delivery at 32 weeks. Tight cord entanglement |

| Abuhamad et al.(21) | 33 | Yes | Normal fetal heart rate monitoring, decreased amniotic fluid. Delivery at 34 weeks. |

| 31 | Yes | Normal heart rate monitoring, umbilical artery notch in both twins. Delivery at 32 weeks | |

| Hugon-Rodin et al.(22) | 31 | Yes | Normal fetal heart rate monitoring, Delivery at 32 weeks |

GA; gestational age; UA: Umbilical artery; US ultrasound

The only report on umbilical artery notching and adverse perinatal outcome in MC/MA twins was by Kofia nas et al. [20]. In this report, when the umbilical artery notch was observed, there was already one fetal demise, and the surviving twin demonstrated an elevated systolic/diastolic ratio in the umbilical artery, pulsation of the umbilical vein and variable decelerations on the nonstress test. Subsequent studies, such as that from Hugon-Rodin et al. [22] and ours, have not found such an association. The presence of an umbilical artery notch in both fetuses was previously reported by Abuhamad et al. [36] with a favorable outcome for both twins. We observed an umbilical artery notch in both co-twins in two pregnancies, one of which had a true knot confirmed after delivery. It is possible that the presence of an umbilical artery notch might be more frequent than expected if the umbilical artery is evaluated in different parts of the umbilical cord. In general, Doppler interrogation of the umbilical artery in twins is done close to the fetal insertion of the cord where a notch is less frequently observed. It might be possible that, when evaluating the vessels involved in the cord entanglement, overlapping of the Doppler spectrum of the two fetuses can give the impression of an umbilical artery notch. Overton et al. [37] described this finding as the ‘galloping’ pattern. The galloping pattern is different from notching of the umbilical artery, as the systolic peaks of the two heart frequencies can be noted at any time during the cardiac cycle. The umbilical artery notch is always observed in the late systolic or early diastolic phase of the cardiac cycle. In addition, the galloping pattern is only observed within the region of cord entanglement, whereas an umbilical artery notch can be observed in a free loop of the umbilical cord.

Placenta and Umbilical Cord Pathology

Cord entanglement was confirmed in all pregnancies at delivery. The high prevalence of cord entanglement has been previously reported, suggesting that it does not necessarily lead to an abnormal perinatal outcome [2, 26, 37–44]. All other placental and umbilical cord findings, such as a true knot, forked placental insertion [45] and the proximity of cord placental insertions to each other, might contribute to the presence of an umbilical artery notch. Fortunately, no signs of fetal deterioration were documented in our cases.

Management of MC/MA Twins

Although intensive surveillance is recommended for MC/MA twins [46–49], controversy exists regarding the frequency and timing of the initiation of tests as well as the optimal gestational age for delivery [48, 50, 51]. Two retrospective cohort studies have demonstrated that early hospitalization between 24 and 28 weeks of gestation accompanied by intensive fetal monitoring and delivery at 32–34 weeks of gestation improved perinatal survival when compared to outpatient management [49, 52]. A close evaluation of these pregnancies might help to identify early signs of fetal deterioration [53]. It is likely that neither the isolated presence of cord entanglement nor the presence of an umbilical artery notch is an indication alone for an emergency delivery. However, the presence of additional abnormalities in the umbilical artery waveform, such as increased PI, reduced diastolic flow [20, 42] or umbilical vein pulsations [34], may suggest tight cord entanglement which could lead to fetal death. Our results suggest that cord entanglement and an umbilical artery notch may be frequent findings in MC/MA twins. However, a tight cord entanglement might lead to severe notching and acute fetal deterioration. Close surveillance of these pregnancies is therefore recommended.

All newborns experienced morbidity related to gestational age at delivery. None of the neonates with intraventricular hemorrhage grade I had further progression. These results suggest that in the absence of signs of fetal deterioration, even when cord entanglement and umbilical artery notching are present, these pregnancies could be prolonged to at least 34 weeks, when the risk of neonatal morbidity is substantially reduced.

Conclusion

In MC/MA twin gestations, the presence of umbilical cord entanglement and umbilical artery notching in the absence of signs of fetal deterioration do not necessarily lead to an adverse perinatal outcome.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported, in part, by the Perinatology Research Branch, Division of Intramural Research, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services (NICHD/NIH), and, in part, with Federal funds from NICHD, NIH under Contract No. HHSN275201300006C.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Sebire NJ, Souka A, Skentou H, Geerts L, Nicolaides KH. First-trimester diagnosis of monoamniotic twin pregnancies. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2000;16:223–225. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0705.2000.00229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lewi L. Cord entanglement in monoamniotic twins: does it really matter? Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2010;35:139–141. doi: 10.1002/uog.7553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lewi L, Gucciardo L, Van Mieghem T, de Koninck P, Beck V, Medek H, et al. Monochorionic diamniotic twin pregnancies: natural history and risk stratification. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2010;27:121–133. doi: 10.1159/000313300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gratacos E, Ortiz JU, Martinez JM. A systematic approach to the differential diagnosis and management of the complications of monochorionic twin pregnancies. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2012;32:145–155. doi: 10.1159/000342751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lewi L, Deprest J, Hecher K. The vascular anastomoses in monochorionic twin pregnancies and their clinical consequences. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;208:19–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quintero RA. Twin-twin transfusion syndrome. Clin Perinatol. 2003;30:591–600. doi: 10.1016/s0095-5108(03)00051-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kusanovic JP, Romero R, Gotsch F, Mittal P, Erez O, Kim CJ, et al. Discordant placental echogenicity: a novel sign of impaired placental perfusion in twin-twin transfusion syndrome? J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2010;23:103–106. doi: 10.3109/14767050903005873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chalouhi GE, Stirnemann JJ, Salomon LJ, Essaoui M, Quibel T, Ville Y. Specific complications of monochorionic twin pregnancies: twin-twin transfusion syndrome and twin reversed arterial perfusion sequence. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2010;15:349–356. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2010.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quintero RA, Reich H, Puder KS, Bardicef M, Evans MI, Cotton DB, et al. Brief report: umbilical-cord ligation of an acardiac twin by fetoscopy at 19 weeks of gestation. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:469–471. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199402173300705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gratacos E, Lewi L, Munoz B, Acosta-Rojas R, Hernandez-Andrade E, Martinez JM, et al. A classification system for selective intrauterine growth restriction in monochorionic pregnancies according to umbilical artery Doppler flow in the smaller twin. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2007;30:28–34. doi: 10.1002/uog.4046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ishii K, Murakoshi T, Takahashi Y, Shinno T, Matsushita M, Naruse H, et al. Perinatal outcome of monochorionic twins with selective intrauterine growth restriction and different types of umbilical artery Doppler under expectant management. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2009;26:157–161. doi: 10.1159/000253880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Valsky DV, Eixarch E, Martinez JM, Gratacos E. Selective intrauterine growth restriction in monochorionic diamniotic twin pregnancies. Prenat Diagn. 2010;30:719–726. doi: 10.1002/pd.2536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cuppett CD, Stitely ML. Diagnosis and management of a monochorionic/monoamniotic twin gestation discordant for fetal anomalies. W V Med J. 2009;105:27–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burguet A, Monnet E, Pauchard JY, Roth P, Fromentin C, Dalphin ML, et al. Some risk factors for cerebral palsy in very premature infants: importance of premature rupture of membranes and monochorionic twin placentation. Biol Neonate. 1999;75:177–186. doi: 10.1159/000014094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Penava D, Natale R. An association of chorionicity with preterm twin birth. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2004;26:571–574. doi: 10.1016/s1701-2163(16)30375-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giuffre M, Piro E, Corsello G. Prematurity and twinning. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012;25(suppl 3):6–10. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2012.712350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DeStephano CC, Meena M, Brown DL, Davies NP, Brost BC. Sonographic diagnosis of conjoined diamniotic monochorionic twins. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203:e4–e6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Omari AA, Cameron D. Getting knotted: umbilical knots in a monochorionic monoamniotic twin pregnancy. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2005;90:F24. doi: 10.1136/adc.2004.061812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deutsch AB, Miller E, Spellacy WN, Mabry R. Ultrasound to identify cord knotting in monoamniotic monochorionic twins. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2007;10:216–218. doi: 10.1375/twin.10.1.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kofinas AD, Penry M, Hatjis CG. Umbilical vessel flow velocity waveforms in cord entanglement in a monoamnionic multiple gestation. A case report. J Reprod Med. 1991;36:314–316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abuhamad AZ, Mari G, Copel JA, Cantwell CJ, Evans AT. Umbilical artery flow velocitywaveforms in monoamniotic twins with cord entanglement. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;86:674–677. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(95)00210-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hugon-Rodin J, Guilbert JB, Baron X, Camus E. Notching of the umbilical artery waveform associated with cord entanglement in a monoamniotic twin pregnancy. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2013;26:1559–1561. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2013.794204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beasley E, Megerian G, Gerson A, Roberts NS. Monoamniotic twins: case series and proposal for antenatal management. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;93:130–134. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(98)00399-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shveiky D, Ezra Y, Schenker JG, Rojansky N. Monoamniotic twins: an update on antenatal diagnosis and treatment. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2004;16:180–186. doi: 10.1080/14767050400013289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baxi LV, Walsh CA. Monoamniotic twins in contemporary practice: a single-center study of perinatal outcomes. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2010;23:506–510. doi: 10.3109/14767050903214590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dias T, Mahsud-Dornan S, Bhide A, Papageorghiou AT, Thilaganathan B. Cord entanglement and perinatal outcome in monoamniotic twin pregnancies. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2010;35:201–204. doi: 10.1002/uog.7501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rossi AC, Prefumo F. Impact of cord entanglement on perinatal outcome of monoamniotic twins: a systematic review of the literature. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2013;41:131–135. doi: 10.1002/uog.12345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Quintero RA, Morales WJ, Allen MH, Bornick PW, Johnson PK, Kruger M. Staging oftwin-twin transfusion syndrome. J Perinatol. 1999;19:550–555. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7200292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lewi L, Van Schoubroeck D, Gratacos E, Witters I, Timmerman D, Deprest J. Monochorionic diamniotic twins: complications and management options. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2003;15:177–194. doi: 10.1097/00001703-200304000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gosling RG, Dunbar G, King DH, Newman DL, Side CD, Woodcock JP, et al. The quantitative analysis of occlusive peripheral arterial disease by a non-intrusive ultrasonic technique. Angiology. 1971;22:52–55. doi: 10.1177/000331977102200109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jakobi P, Weiner Z, Goren T, Thaler I. Systolic notch in umbilical artery flow velocity waveforms associated with a tight true knot of the cord. J Matern Fetal Invest. 1994;4:119–121. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robinson JN, Abuhamad AZ, Sayed A, Evans AT. Umbilical artery Doppler velocimetry waveform notching and umbilical cord abnormalities. J Ultrasound Med. 1997;16:373–375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Entezami M, Ragosch V, Hopp H, Weitzel HK, Runkel S. Notch in the umbilical artery Doppler profile in umbilical cord compression in a twin (in German) Ultraschall Med. 1997;18:277–279. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1000442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Suzuki S, Ishikawa G, Sawa R, Yoneyama Y, Asakura H, Araki T. Umbilical venous pulsation indicating tight cord entanglement in monoamniotic twin pregnancy. J UltrasoundMed. 1999;18:425–427. doi: 10.7863/jum.1999.18.6.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Robinson JN, Abuhamad AZ, Evans AT. Umbilical artery Doppler velocimetry waveform abnormality in fetal gastroschisis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1997;10:356–358. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0705.1997.10050356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abuhamad A, Sclater AJ, Carlson EJ, Moriarity RP, Aguiar MA. Umbilical artery Doppler waveform notching: is it a marker for cord and placental abnormalities? J Ultrasound Med. 2002;21:857–860. doi: 10.7863/jum.2002.21.8.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Overton TG, Denbow ML, Duncan KR, Fisk NM. First-trimester cord entanglement in monoamniotic twins. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1999;13:140–142. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0705.1999.13020140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nyberg DA, Filly RA, Golbus MS, Stephens JD. Entangled umbilical cords: a sign of monoamniotic twins. J Ultrasound Med. 1984;3:29–32. doi: 10.7863/jum.1984.3.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Belfort MA, Moise KJ, Jr, Kirshon B, Saade G. The use of color flow Doppler ultrasonography to diagnose umbilical cord entanglement in monoamniotic twin gestations. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;168:601–604. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(93)90502-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aisenbrey GA, Catanzarite VA, Hurley TJ, Spiegel JH, Schrimmer DB, Mendoza A. Monoamniotic and pseudomonoamniotic twins: sonographic diagnosis, detection of cord entanglement, and obstetric management. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;86:218–222. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(95)00130-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shahabi S, Donner C, Wallond J, Schlikker I, Avni EF, Rodesch F. Monoamniotic twin cord entanglement. A case report with color flow Doppler Ultrasonography for antenatal diagnosis. J Reprod Med. 1997;42:740–742. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rosemond RL, Hinds NE. Persistent abnormal umbilical cord Doppler velocimetry in a monoamniotic twin with cord entanglement. J Ultrasound Med. 1998;17:337–338. doi: 10.7863/jum.1998.17.5.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tongsong T, Chanprapaph P. Picture of the month. Evolution of umbilical cord entanglement in monoamniotic twins. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1999;14:75–77. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0705.1999.14010075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Arabin B, Hack K. Is the location of cord entanglement associated with antepartum death in monoamniotic twins? Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2009;33:246–247. doi: 10.1002/uog.6290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fraser RB, Liston RM, Thompson DL, Wright JR., Jr Monoamniotic twins delivered liveborn with a forked umbilical cord. Pediatr Pathol Lab Med. 1997;17:639–644. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rodis JF, McIlveen PF, Egan JF, Borgida AF, Turner GW, Campbell WA. Monoamniotic twins: improved perinatal survival with accurate prenatal diagnosis and antenatal fetal surveillance. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;177:1046–1049. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(97)70012-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Demaria F, Goffinet F, Kayem G, Tsatsaris V, Hessabi M, Cabrol D. Monoamniotic twin pregnancies: antenatal management and perinatal results of 19 consecutive cases. BJOG. 2004;111:22–26. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-0528.2003.00009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ezra Y, Shveiky D, Ophir E, Nadjari M, Eisenberg VH, Samueloff A, et al. Intensive management and early delivery reduce antenatal mortality in monoamniotic twin pregnancies. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2005;84:432–435. doi: 10.1111/j.0001-6349.2005.00683.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Heyborne KD, Porreco RP, Garite TJ, Phair K, Abril D. Improved perinatal survival of monoamniotic twins with intensive inpatient monitoring. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:96–101. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Allen VM, Windrim R, Barrett J, Ohlsson A. Management of monoamniotic twin pregnancies: a case series and systematic review of the literature. BJOG. 2001;108:931–936. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2001.00216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hack KE, Derks JB, Schaap AH, Lopriore E, Elias SG, Arabin B, et al. Perinatal outcome of monoamniotic twin pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113:353–360. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318195bd57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.DeFalco LM, Sciscione AC, Megerian G, Tolosa J, Macones G, O’Shea A, et al. Inpatient versus outpatient management of monoamniotic twins and outcomes. Am J Perinatol. 2006;23:205–211. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-934091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pan M, Chen M, Leung TY, Sahota DS, Ting YH, Lau TK. Outcome of monochorionic twin pregnancies with abnormal umbilical artery Doppler between 16 and 20 weeks of gestation. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012;25:277–280. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2011.573830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]