Abstract

Greater than 99% of the mitochondrial proteome is nuclear-encoded. The mitochondrion relies on a coordinated multi-complex process for nuclear genome-encoded mitochondrial protein import. Mitochondrial heat shock protein 70 (mtHsp70) is a key component of this process and a central constituent of the protein import motor. Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) disrupts mitochondrial proteomic signature which is associated with decreased protein import efficiency. The goal of this study was to manipulate the mitochondrial protein import process through targeted restoration of mtHsp70, in an effort to restore proteomic signature and mitochondrial function in the T2DM heart. A novel line of cardiac-specific mtHsp70 transgenic mice on the db/db background were generated and cardiac mitochondrial subpopulations were isolated with proteomic evaluation and mitochondrial function assessed. MicroRNA and epigenetic regulation of the mtHsp70 gene during T2DM were also evaluated. MtHsp70 overexpression restored cardiac function and nuclear-encoded mitochondrial protein import, contributing to a beneficial impact on proteome signature and enhanced mitochondrial function during T2DM. Further, transcriptional repression at the mtHSP70 genomic locus through increased localization of H3K27me3 during T2DM insult was observed. Our results suggest that restoration of a key protein import constituent, mtHsp70, provides therapeutic benefit through attenuation of mitochondrial and contractile dysfunction in T2DM.

Keywords: Diabetes Mellitus, Mitochondria, Cardioprotection, Mitochondrial Heat Shock Protein 70, Mitochondrial Protein Import, Proteomics, Epigenetics, Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus

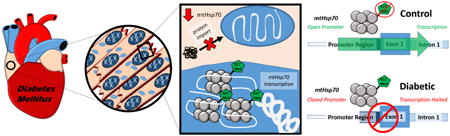

Graphical abstract

Approximately 1500 proteins reside in the human mitochondrion, with 13 encoded by the mitochondrial genome and the remaining proteins (>99%) encoded by the nuclear genome [1-3]. To maintain an appropriate proteomic signature, the mitochondrion relies on a coordinated multi-complex process for nuclear genome-encoded mitochondrial protein import, which includes mitochondrial heat shock protein 70 (mtHsp70) [4]. Located in the mitochondrial matrix, mtHsp70 is a central subunit of the presequence translocase-associated motor (PAM) complex [4]. Anchored to the translocase of the inner membrane 44 (Tim44), mtHsp70 attaches to a translocating preprotein, thereby trapping and pulling it through the inner mitochondrial membrane in an active ATP-dependent manner. When mtHsp70 levels are decreased, mitochondrial function is compromised with decrements noted in nuclear genome-encoded mitochondrial protein import, decreased mitochondrial antioxidant defense, increased protein misfolding and enhanced protein degradation, along with increased cellular apoptosis [4]. Neonatal rat cardiomyocytes infected with an adenoviral vector expressing mtHsp70 were protected from ischemia/reperfusion injury, potentially from an increased import of nuclear genome-encoded antioxidant defense proteins [5].

Epigenetic regulation primarily involves histone modifications, through histone acetylases/deacetylases [6] and polycomb repressive complex 1/2 (PCR1 and PCR2) [7], and DNA methylation, through DNA methyltransferases [8]. These epigenetic marks result in transcriptional activation or repression, which can be sustained, removed, or propagated over genetic locales during pathological development. Global DNA methylation has been shown to increase in peripheral blood leukocytes [9], while differential methylation patterns in the blood as a whole have been linked to the development of type 2 diabetes mellitus [10]. Global histone modifications have been associated with the development of diabetes mellitus [11]. Two common histone modifications include the activating histone 3 lysine 4 tri-methylation (H3K4me3) and the repressive histone 3 lysine 27 tri-methylation (H3K27me3) marks [12]. Examination of histone modifications during diabetic conditions, provides insight into programmed communication between nuclear, cytoplasmic and mitochondrial compartments. At both the human HSPA9 and mouse Hspa9 genetic loci, DNA methylation (through CpG islands) and histone modifications (such as H3K4me3 and H3K27me3) are known to occur and could influemce gene expression.

Mitochondrial dysfunction in the type 2 diabetic heart occurs primarily in subsarcolemmal mitochondria (SSM), as opposed to interfibrillar mitochondria (IFM), with disruption of SSM proteomic signature, including loss of mtHsp70 protein content [13, 14]. These observations suggest that mtHsp70 may represent a central regulatory node for mitochondrial proteome disruption in the type 2 diabetic heart resulting from anterograde epigenetic signaling between nuclear and mitochondrial compartments [15]. The goal of the current study was to determine whether cardiac-specific overexpression of mtHsp70 in a type 2 diabetic model (db/db) could restore proteomic signature in type 2 diabetic cardiac mitochondria through restoration of nuclear genome-encoded mitochondrial protein import, with additional evaluation of the epigenetic landscape dynamics at the mtHsp70 nuclear locus.

Research Design and Methods

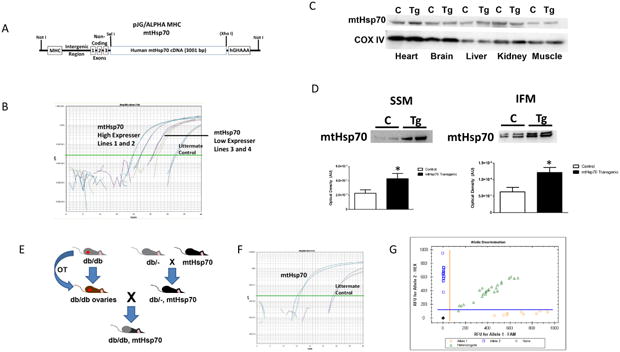

MtHsp70 Transgenic Mouse Development

Animal experiments in this study conformed to the National Institutes of Health Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the West Virginia University Care and Use committee. Cardiac-specific mtHsp70 transgenic mouse lines were generated using a chimeric transgene consisting of the human HSPA9 gene inserted into the plasmid pJG/Alpha MHC vector containing an alpha-myosin heavy-chain (αMHC) promoter (a kind gift from Dr. Jeffrey Robbins) [16] (Figure 1A). The HSPA9 gene consists of a 5′ mitochondrial targeting sequence (ATG) and the human mtHsp70 cDNA, which was inserted into the Sal1 cloning site of the pJG/Alpha MHC vector via sticky-end and blunt-end ligation of Xho1 and HindIII, as a fragment of approximately 3001 bp (Figure 1A). The chimeric transgene was cut out of the plasmid by Not1 digestion, purified, and used to generate transgenic mice by the Mouse Transgenic and Gene Targeting Core at Emory University as described previously [17-19]. All control and transgenic mice were generated using a FVB background, and experimental procedures were performed on animals of approximately 20-22-weeks-old.

Figure 1. MtHsp70 transgenic mouse construction.

(A) Schematic of the generation of mtHsp70 transgenic mice. (B) Verification of transgene presence using real-time PCR. (C) Representative Western blot analysis of mtHsp70 protein expression in isolated tissues from control and mtHsp70 transgenic mice. CoxIV was used a loading control. (D) Representative Western blot analysis and quantification of cardiac mitochondrial subpopulations from control and mtHsp70 transgenic mice loaded per mitochondria. (E) Schematic representation of breeding strategy for mtHsp70 db/db mice. (F) Verification of transgene presence using real-time PCR. (G) Allelic discrimination screening. C = control; Tg = transgenic. Values are expressed as means ± SEM. *P ≤ 0.05 for control vs. transgenic.

MtHsp70 Transgenic Mouse Screening

To verify chimeric transgene presence, DNA was isolated from tail clips using Allele-In-One Mouse Tail Direct Lysis Buffer (Allele Biotechnology, San Diego, CA) per manufacturer's instructions and screened as previously described [17-19]. Four transgenic mouse lines were generated, with two high expressing transgenic lines (20-22 cycle number) and two low expressing transgenic lines (26-28 cycle number). One of the high, mtHSP70 expressing lines (Line 1) was used for all subsequent studies. The use of a high expressing line was implemented in order to accurately assess expression levels that may be modelled therapeutically, as well as providing a more pronounced phenotype for observation. (Figure 1B).

Ovarian Transplantation Procedure

A db/db, mtHsp70 transgenic mouse line was generated using an ovarian transplantation procedure developed in our laboratory. Briefly, a db/db donor mouse was euthanized by cervical dislocation, an incision made in the abdominal wall, followed by the exteriorization of the ovarian fat pad. Ovaries were removed for implantation into recipient mice.

The recipient mouse was maintained under a surgical plane of anesthesia, an incision made in the abdominal cavity and the ovarian fat pad exteriorized. The ovarian bursa was incised cranially at the junction of the bursa and the fat pad to enable access to the ovary. The donor ovary was placed on top of the ovarian blood vessels and the bursa retracted into its original position. The fat pad and ovary were returned into the abdominal cavity and the incision in the abdominal wall closed. Removal of the contralateral ovary was performed.

MtHsp70 Db/Db Transgenic Mouse Screening

The developmental strategy for ovarian transplantation and breeding can be seen in Figure 1E. Briefly, ovaries from a homozygous FVB-db/db female mouse were excised and then implanted into an immunohistocompatible recipient mouse. This recipient mouse was bred with a mouse heterozygous for both the db/db and mtHsp70 genotype. MtHsp70 genotyping was completed as described above (Figure 1F). To determine whether the offspring possessed the db/db mutation, DNA was amplified via PCR for the Leprdb locus followed by allelic discrimination analysis using fluorometric probes designed by our laboratory to identify Leprdb/db homozygous (db/db), Leprdb/- heterozygous (db/-) or control (-/-) offspring (Figure 1G). The sequence containing the mutation was tagged with FAM, while the normal sequence was tagged with HEX enabling assessment of whether the DNA contained 2 HEX tags (-/-), a HEX tag and a FAM tag (db/-), or 2 FAM tags (db/db) (Figure 1G). DNA from known db/db, db/-, and -/- mice obtained from and validated by Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) were included as internal controls. Once appropriate genotypes were obtained, mixed sex animals were aged to 20-22-weeks-old, echocardiography performed and euthanized for experimentation. All animals used in the study were in the FVB background. No differences were observed in heart weight or total body weight between the db/db and transgenic mtHsp70 db/db animals (data not included).

Echocardiography

Echocardiography and speckle-tracking based strain imaging analyses were performed as previously described using the Vevo 2100 Imaging analysis software (Visual Sonics, Toronto, Canada) [17, 19-21].

Preparation of Individual Mitochondrial Subpopulations

Cardiac mitochondrial subpopulations were isolated as previously described following the methods of Palmer et al. [22] with minor modifications by our laboratory [13, 17-19, 21, 23-25]. Protein concentrations were determined by the Bradford method with bovine serum albumin as a standard [26], while mitochondrial number was determined by flow cytometry.

Determination of Mitochondrial Number by Flow Cytometry

Mitochondrial number was determined using Sphero AccuCount Blank Particles, 2.0 μm (Spherotech Inc., Lake Forest, IL). Mitochondria were diluted in sucrose buffer (1:2,500) and subsequently stained with Mitotracker Deep Red 633 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), resulting in event rates below 1,000 events/s using FACSDiva 8.0 software (BD Biosciences, San Jose CA) on an LSRFortessa equipped with a FSC PMT (BD Biosciences) in the West Virginia University Flow Cytometry and Single Cell Core Facility. Events were determined as mitochondria by thresholding on Mitotracker Deep Red 633. Sphero AccuCount blank particles were run for 1 minute to obtain the number of events. Mitochondrial number was calculated per manufacturer's instructions.

iTRAQ Labeling and Mass Spectrometry Analyses

Pooled mitochondrial samples were prepared as previously described [13, 17, 23]. Samples were labeled with iTRAQ reagents following the manufacturer's protocol (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and combined to create a 400 μg pooled protein digest with equal fractions of labeled samples. Samples (n = 8 biological replicates) were pooled for each condition (wild type, db/db, transgenic, and transgenic/db/db) and mitochondrial subpopulation (SSM and IFM). 200 μg injections were submitted for LC-MS/MS mass spectral analysis for protein identification, characterization, and differential expression analysis as previously described [13, 23] with slight modifications. Briefly, a Q Exactive mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, San Jose, CA) running Xcalibur 3.0 software was integrated with an Acquity UHPLC (Waters Corp, Milford, MA) for LC-MS/MS analysis. An Acquity CSH C18, 1 × 150 mm (130 Å, 1.7 μm) column was used with a column temperature of 60°C, an autosampler set point at 4°C for sample cooling, an injection volume of 18 μL, and a linear HPLC gradient at 100 μL/min for 170 minutes (1-38% B, where A = 0.1% formic acid and B = 0.1% formic acid in 100% acetonitrile). The mass spectrometer settings for LC-MS/MS analysis included mass range 250-2000 m/z, a top 10 data dependent acquisition mode, precursor (MS mode) resolution at 70,000, and fragment ion mode (MS/MS) resolution at 17,500. The resulting spectra were analyzed using ABI ProteinPilot software 4.0 (Paragon algorithm) equipped with universal data option to accept Thermo raw files (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Data analysis parameters for the ProteinPilot software included positive selections for sample type (iTRAQ 4plex / peptide labeled), digestion (trypsin), cysteine alkylation (MMTS), instrument (Orbi MS, Orbi MS/MS), species (mus musculus), ID focus (biological modifications), and FDR analysis (1% Global FDR). The proteome was aligned to Uniprot's reviewed sequences through Swiss-Prot for the mouse genome, UP000000589 10090 MOUSE Mus musculus. Complete proteomic analyses, including peptide alignments, were uploaded to PeptideAtlas (http://www.peptideatlas.org/). Identifier: PASS01174, Dataset title: Murine LC-MS/MS mtHSP70 transgenic Heart.

Ingenuity Pathway Analyses

Proteomic data was integrated into the Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) software to establish associations between changing mitochondrial protein constituents and upstream/downstream effects on cellular pathways. The “Mitochondrial Dysfunction Metabolic Pathway” was generated through the use of QIAGEN's IPA (www.qiagen.com/ingenuity) and used as the basic model for protein associations.

Mitochondrial Protein Import

Mitochondrial protein import efficiency was carried out as previously described [27] with modifications by our laboratory [17, 23], using an S30 T7 protein expression system (Promega, Madison, WI) [17, 23]. Briefly, mitochondria were counted by flow cytometry, MitoGFP1 lysate added to the samples, protein import performed and assessed at time intervals of 30 s, 1 and 2 mins [17, 23].

Electron Transport Chain Complex Activities

Assessment of mitochondrial complex activity was performed spectrophotometrically as previously described [13, 28-30]. Values for complex activities were expressed as nanomoles substrate converted/min/mitochondrial number.

Mitochondrial Respiration

State 3 and state 4 respiration rates were analyzed in mitochondrial subpopulations as previously described [31, 32] with modifications by our laboratory [13, 14, 18, 19]. Data for state 3 (250 mM ADP) and state 4 (ADP-limited) respiration were expressed as nanomoles of oxygen consumed/min/mitochondrial number.

Human Patient Samples

The West Virginia University Institutional Review Board and Institutional Biosafety Committee approved all protocols. Patient demographics have been described and characterized as non-diabetic or type 2 diabetic based on previous diagnoses [14, 19]. Briefly, human right atrial tissue was removed following coronary artery bypass graft (CABG). The authors note the limitations of functional analyses performed on atrial, rather than ventricular, cardiac tissue. The availability of atrial tissue provides the most feasible, translational model for work with fresh human cardiac tissue.

Western Blot Analyses

SDS-PAGE was run on 4-12% gradient gels, as previously described [13, 17, 19, 21, 23, 33, 34]. For assessment of protein content overexpression and mitochondrial protein import, 100 million intact mitochondria were loaded as determined by flow cytometry. For assessment of protein content in human samples and tissue homogenates, equal amounts of protein were loaded as determined by the Bradford method [26]. Assessment of protein loading control was done by utilizing a COXIV antibody and Ponceau S solution (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Relative amounts of mtHsp70 and COXIV were assessed using primary and secondary antibodies (Supplemental Table 1). Densitometry analyses using Image J software, were performed as previously described [17-19, 21, 23, 35].

Quantitative PCR

RNA was isolated from human atrial appendage and cardiac mouse tissue using the miRNeasy® Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD, Catalog #: 217004), per manufacturer's instructions. RNA was converted to cDNA using a First-strand cDNA Synthesis kit for miRNA (Origene, Rockville, MD, Catalog #: HP100042), per manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, the kit uses poly-A adenylation of transcripts, allowing for standardized reverse primers for small RNAs. The cDNA was used for both miRNA and mRNA assessment. For qPCR primer characteristics and additional methodology regarding primer design, refer to Supplemental Table 2. MiRNAs, which had a predictive score greater than or equal to 80 but were not found to be complementary between both the HSPA9 and Hspa9 genes were also assessed (Supplemental Figure 2) [36, 37]. For small RNA assessment, the U6 reporter gene was used as a control. The mRNA of transcripts within the PCR2 complex were normalized to GAPDH. Chromatin-immunoprecipitation (ChIP)-qPCR was normalized to the input control for each sample. Experiments were performed on the Applied Biosystems 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), using 2× SYBR Green Master Mix. Quantification was achieved using the 2-ΔΔCT method.

Histone Methyltransferase Activity

Global H3K27me3 levels were assessed using the EpiQuik™ Global Tri-Methyl Histone H3-K27 Quantification Kit (Colorimetric), per manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, nuclear fractions were isolated using differential centrifugation [13, 17, 18]. 2 μg of nuclear fractions were run in triplicate for each sample, prepared on anti-H3K27me3 antibody coated strip wells. Colorimetric analyses was performed using the Flexstation 3 Luminometer (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

DNA Methylation

DNA was isolated from frozen tissue using a DNeasy® Blood & Tissue kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD, Catalog #: 69504), per manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, human atrial appendage and mouse cardiac tissue were lysed and DNA isolated using spin column purification. DNA was bisulfite treated with the EZ DNA Methylation-Lightning™ Kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA, Catalog #: D5031) per manufacturer's instructions, allowing the conversion of unmethylated cytosines to thymine bases. Primers were designed to span a portion of the CpG island located at the promoter region of the HSPA9 and Hspa9 genes (Supplemental Table 2). Platinum™ Taq DNA Polymerase (Thermo Fisher, Rockford, IL, Catalog #: 10966026) was used to amplify CpG islands. PCR products were run on a 2% agarose gel and bands were excised and purified with a QIAquick®Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD, Catalog #: 28704), per manufacturer's instructions. Purified DNA was incorporated into a TOPO plasmid and transfected into DH5α cells using a TOPO™ TA Cloning™ Kit for Sequencing, with One Shot™ TOP10 Chemically Competent E. coli (Thermo Fisher, Rockford IL, Catalog #: K457501), per manufacturer's instructions. Ten colonies per group were selected and further grown in liquid culture containing 100 ug/mL ampicillin for 18 hours. Plasmids were isolated using a QIAprep® Spin Miniprep Kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD, Catalog #: 27104), per manufacturer's instructions. Plasmids were sent to the West Virginia University Genomics Core Facility for Sanger sequencing. Forward and reverse reads of the TOPO plasmid were accomplished using the M13 Forward (-20) and M13 Reverse primers.

Histone Modifications

ChIP was performed on human atrial appendage and mouse cardiac tissue using a Zymo-Spin™ ChIP Kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA, Catalog #: D5210), per manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, tissue was homogenized using a PowerGen™ 500 tissue homogenizer (Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and transiently crosslinked with 37% formaldehyde (prepared fresh). Crosslinking was stopped with 1M glycine and chromatin shearing was conducted using Q125 Sonicator (Qsonica, Newtown, CT, Catalog #: Q125-110) for four cycles (30 sec “ON”, 30 sec “OFF”, 40% amplitude) on ice. Chromatin marks studied in the experiment were histone 3 lysine 4 tri-methylation (H3K4me3, Thermo Fisher, Rockford IL, Catalog #: G.532.8) and histone 3 lysine 27 tri-methylation (H3K27me3, Thermo Fisher, Rockford IL, Catalog #: G.299.10). The DNA recovered from the ChIP procedure was then used for qPCR (Supplemental Table 2).

Statistics

All data are presented as mean±standard error of the mean (SEM). Data were analyzed using a One-Way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) with the Bonferroni post-hoc test to determine significant differences between groups (GraphPad Prism 5 Software, La Jolla, CA). When differences in variability between groups was noted by Bartlett's test for equal variances, a Kruskal-Wallis analysis was utilized with the Dunn's multiple comparison tests to assess differences between groups. When appropriate, a Student's t-test was used. In all instances, P≤0.05 was considered significant.

Results

MtHsp70 Transgenic Mice Characterization

MtHsp70 transgenic mice possessed higher levels of mtHsp70 protein solely in cardiac tissue, with no changes in any other tissue type (Figure 1C). To determine whether mtHsp70 expression was increased in the mitochondrion, we assessed mtHsp70 protein levels in cardiac mitochondrial subpopulations and observed a significant increase in its expression in both the SSM and IFM (Figure 1D).

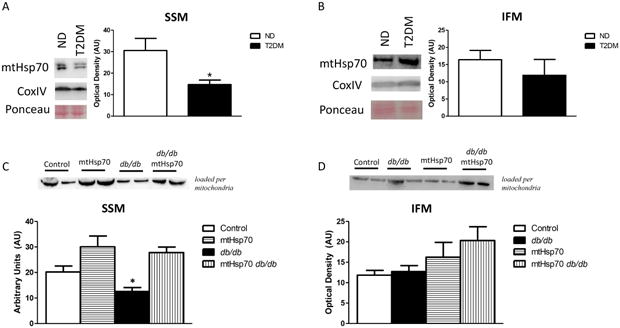

Evaluation of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus on mtHsp70

MtHsp70 content in the SSM of type 2 diabetic patients was decreased as compared to non-diabetic patients, with no changes observed in the IFM (Figure 2A-B). MtHsp70 protein levels were decreased in the SSM of db/db mice, however, mtHsp70 overexpression restored these levels (Figure 2C). IFM were not significantly impacted by type 2 diabetes mellitus (Figure 2D).

Figure 2. Mitochondrial heat shock protein 70 (mtHsp70) levels.

(A) Representative Western blot analysis and quantification of SSM and (B) IFM in cardiac mitochondria isolated from human atrial appendage in ND (n = 5) and type 2 diabetic patients (n = 5). CoxIV and Ponceau staining were used as loading controls. (C) Representative Western blot analysis and quantification of mtHsp70 protein expression in SSM (n = 6, each group) of wild-type, type 2 diabetic, mtHsp70, and mtHsp70 type 2 diabetic mice loaded per mitochondria. (D) Representative Western blot analysis and quantification of mtHsp70 protein expression in IFM (n = 6, each group) of wild-type, type 2 diabetic, mtHsp70, and mtHsp70 type 2 diabetic mice loaded per mitochondria. ND = non-diabetic; T2DM = type 2 diabetes mellitus; Ctl = control. Values are expressed as means ± SEM. *P ≤ 0.05 for ND vs diabetes mellitus; †P ≤ 0.05 for mtHsp70 T2DM vs other groups.

Cardiac Contractile Function

Heart rate, ejection fraction (EF) and fractional shortening (FS) were significantly decreased in db/db mice relative to control, however, mtHsp70 overexpression restored these measures (Table 1). Diametric and volumetric changes in the left ventricle (LV) during systole were increased in db/db mice, and attenuated with mtHsp70 overexpression (Table 1). Evaluation of speckle-tracking based strain revealed significant decreases in longitudinal strain (LS) and longitudinal strain rate (LSR) of db/db mice as compared to controls which was restored with mtHsp70 overexpression (Table 1). Using LS regional measurements, we assessed the impact of type 2 diabetes mellitus on the six segments that compose the LV: Posterior Apex (PA), Posterior Mid (PM), Posterior Base (PB), Anterior Apex (AA), Anterior Mid (AM) and Anterior Base (AB). We observed significant decreases in the PB, PA and AM regions in db/db mice, with mtHsp70 overexpression providing restoration to the PB and PA regions (Table 1). LSR regional analyses revealed decreased function in the PA, PB, AB, AM, and AA regions in db/db mice, with mtHsp70 overexpression preserving function in the PB, PA, and AM regions (Table 1).

Table 1. T2DM Echocardiographic Measurements.

| Conventional Echocardiographic Assessment | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | T2DM | mtHsp70 | mtHsp70 T2DM | |

| Heart Rate (bpm) | 523.3 ± 16.5 | 430.3 ± 16.6* | 500.3 ± 9.3 | 459.9 ± 38.8 |

| Stroke Volume (μL) | 27.3 ± 3.7 | 28.3 ± 2.8 | 27.9 ± 1.8 | 35.3 ± 4.7 |

| Ejection Fraction (%) | 77.6 ± 1.7 | 65.4 ± 1.7* † ¥ | 82.7 ± 1.5 | 82.9 ± 2.3 |

| Fractional Shortening (%) | 42.3 ± 1.6 | 35.0 ± 1.3* † ¥ | 50.4 ± 1.7 | 50.9 ± 2.4 |

| Cardiac Output (mL/min) | 13.7 ± 1.5 | 12.0 ± 1.2 | 13.9 ± 0.8 | 16.0 ± 2.0 |

| Diameter;systole (mm) | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 2.1 ± 0.1† | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 1.6 ± 0.2 |

| Diameter;diastole (mm) | 3.0 ± 0.2 | 3.3 ± 0.2 | 2.9 ± 0.1 | 3.2 ± 0.2 |

| Volume;systole (μL) | 6.7 ± 1.5 | 15.7 ± 2.3* † | 5.9 ± 0.7 | 8.0 ± 2.3 |

| Volume;diastole (μL) | 30.8 ± 5.4 | 44.0 ± 4.9 | 33.8 ± 2.3 | 43.3 ± 7.0 |

| Speckle-tracking Based Strain Echocardiographic Assessment | ||||

| Longitudinal Strain (%) | -18.2 ± 0.8 | -13.97 ± 1.0* ¥ | -17.69 ± 1.6 | -17.68 ± 1.0 |

| Posterior Base (%) | -18.4 ± 2.4 | -10.5 ± 1.8* ¥ | -14.4 ± 3.5 | -19.5 ± 3.1 |

| Posterior Mid (%) | -13.8 ± 1.8 | -19.0 ± 1.6 | -20.0 ± 4.3 | -15.8 ± 2.4 |

| Posterior Apex (%) | -33.3 ± 2.5 | -22.6 ± 3.0* ¥ | -28.4 ± 3.4 | -34.4 ± 2.2 |

| Anterior Base (%) | -20.0 ± 2.7 | -18.2 ± 3.0 | -19.0 ± 2.3 | -20.5 ± 4.6 |

| Anterior Mid (%) | -16.6 ± 1.0 | -12.3 ± 1.5* † | -17.9 ± 2.0 | -15.6 ± 2.0 |

| Anterior Apex (%) | -23.0 ± 1.9 | -20.1 ± 1.2 | -24.8 ± 3.3 | -17.8 ± 1.4 |

| Longitudinal Strain Rate (1/s) | -7.2 ± 0.7 | -4.77 ± 0.3* † ¥ | -6.43 ± 0.6 | -6.79 ± 0.6 |

| Posterior Base (1/s) | -10.0 ± 1.2 | -7.1 ± 0.6* † ¥ | -10.4 ± 1.5 | -11.8 ± 1.1 |

| Posterior Mid (1/s) | -7.1 ± 0.7 | -8.3 ± 0.7 | -10.0 ± 1.7 | -7.7 ± 0.5 |

| Posterior Apex (1/s) | -15.5 ± 2.1 | -8.2 ± 0.7* ¥ | -12.1 ± 1.9 | -14.0 ± 1.7 |

| Anterior Base (1/s) | -13.8 ± 1.9 | -7.4 ± 1.0* † | -12.5 ± 1.6 | -9.3 ± 0.7 |

| Anterior Mid (1/s) | -9.3 ± 0.6 | -5.4 ± 0.6* † ¥ | -9.8 ± 0.9 | -8.0 ± 0.7 |

| Anterior Apex (1/s) | -10.8 ± 1.0 | -7.7 ± 0.7* | -9.3 ± 1.3 | -8.5 ± 0.4 |

Values are shown as mean±SEM. N = 8 per group.

P<0.05 Control versus T2DM animals;

P<0.05 T2DM versus mtHsp70 animals;

P<0.05 T2DM versus mtHsp70 T2DM animals. 1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's. Multiple

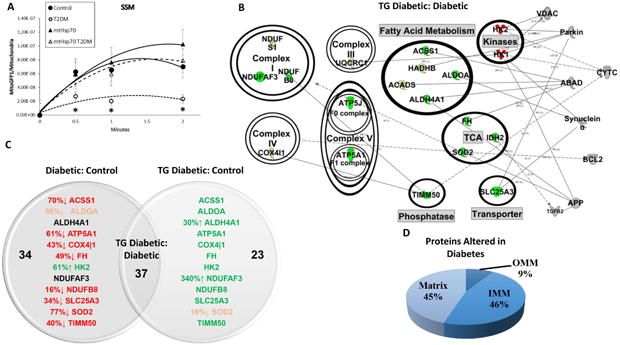

Mitochondrial Protein Import and Proteomic Alterations

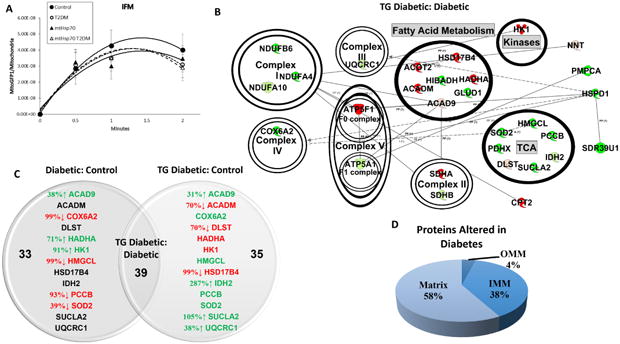

Protein import efficiency in db/db SSM was decreased relative to control at the 30s, 1 min and 2 min time points (Figure 3A). MtHsp70 overexpression restored protein import efficiency in the db/db SSM back to that of control levels, while db/db IFM displayed no import deficiencies (Figure 4A). Similarly, in proteins that are shown to be altered between db/db and db/db mtHsp70, the SSM displayed a much greater augmentation of total gene expression (89% increased; Figure 3B) compared to the IFM (65% increased; Figure 4B). Db/db SSM sustained much greater proteomic alterations, and subsequent recovery with mtHsp70 overexpression (Figure 3C) than db/db IFM (Figure 4C). Also, the number of proteins significantly changed in db/db mtHsp70 mice relative to control was much lower in the SSM (23 proteins) compared to the IFM (35 proteins). A differential impact of the diabetic condition on submitochondrial compartments was apparent, with a greater number of alterations to the SSM inner mitochondrial membrane proteins (Figure 3D) compared to matrix proteins in the IFM (Figure 4D). A complete list of proteomic changes is also provided (Supplemental Table 3). The mtHsp70 overexpressing animal model transcribes a human isoform of the mtHsp70 protein, meaning that its expression in the mitochondrion is not detectable through proteomic analyses running against the murine proteome.

Figure 3. Effects of type 2 diabetes mellitus and mtHsp70 overexpression on SSM.

(A) Effect of type 2 diabetes mellitus and mtHsp70 overexpression on MitoGFP1 import into the SSM at 30 seconds, 1 minute and 2 minutes. Control (n = 10), db/db (n = 7), mtHsp70 (n = 9), and mtHsp70 db/db (n = 7) for IFM import. (B) SSM from mtHsp70 db/db and db/db mice representative network connections constructed from the Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) software database. Arrow heads indicate proteins acting on/being acted upon within a specific pathway. Coloring is indicative of increasing or decreasing protein concentration in the mtHsp70 db/db mouse model compared to db/db mice. Color key: light green = trending increase in expression, dark green = significant increase in expression, light red = trending decrease in expression, dark red = significant decrease in expression, gray = protein constituents not changing in the proteomic analysis. (C) Venn Diagram illustrating the detrimental effects of diabetes mellitus to the mitochondrial proteome (Diabetic:Control) and the recovery seen with the expression of the mtHsp70 transgene during diabetes mellitus (TG Diabetc:Control). Arrows and percentages indicate the direction and extent of protein change, respectively. Red = decreased expression relative to control or reduced expression to control levels for the mtHsp70 db/db. Green = increased expression relative to control or recovered expression to control levels for the mtHsp70 db/db. (D) Approximate percentages of protein contents altered and their locales between the db/db SSM vs. mtHsp70 db/db SSM. Proteomic analysis was conducted on a pooled n = 8 samples from each group. TCA = tricarboxylic acid cycle; OMM = outer mitochondrial membrane; IMM = inner mitochondrial membrane. Values are expressed as means ± SEM. *P ≤ 0.05 for control vs. T2DM. T2DM = type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Figure 4. Effects of type 2 diabetes mellitus and mtHsp70 overexpression on IFM.

(A) Effect of type 2 diabetes mellitus and mtHsp70 overexpression on MitoGFP1 import into the IFM at 30 seconds, 1 minute and 2 minutes. Control (n = 10), db/db (n = 7), mtHsp70 (n = 9), and mtHsp70 db/db (n = 7) for IFM import. (B) IFM from mtHsp70 db/db and db/db mice representative network connections constructed from the Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) software database. Arrow heads indicate proteins acting on/being acted upon within a specific pathway. Coloring is indicative of increasing or decreasing protein concentration in the mtHsp70 db/db mouse model compared to db/db mice. Color key: light green = trending increase in expression, dark green = significant increase in expression, light red = trending decrease in expression, dark red = significant decrease in expression. (C) Venn Diagram illustrating the detrimental effects of diabetes mellitus to the mitochondrial proteome (Diabetic:Control) and the recovery seen with the expression of the mtHsp70 transgene during diabetes (TG Diabetc:Control). Arrows and percentages indicate the direction and extent of protein change, respectively. Red = decreased expression relative to control or reduced expression to control levels for the mtHsp70 db/db. Green = increased expression relative to control or recovered expression to control levels for the mtHsp70 db/db. (D) Approximate percentages of protein contents altered and their locales between the db/db IFM vs. mtHsp70 db/db IFM. Proteomic analysis was conducted on a pooled n = 8 samples from each group. TCA = tricarboxylic acid cycle; OMM = outer mitochondrial membrane; IMM = inner mitochondrial membrane. Values are expressed as means ± SEM. *P ≤ 0.05 for control vs. T2DM. T2DM = type 2 diabetes mellitus.

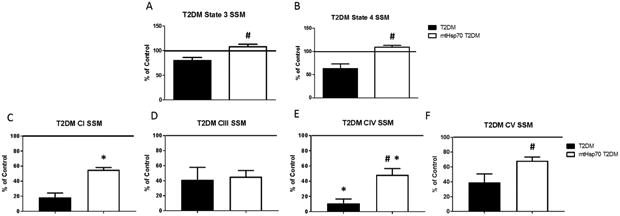

Mitochondrial Respiration and Electron Transport Chain Complex Activities

SSM state 3 and state 4 mitochondrial respiration rates in db/db mtHsp70 mice were significantly higher as compared to db/db (Figure 5A-B). Similarly, SSM electron transport chain complexes I, IV, and V activities exhibited significantly higher enzymatic activity in db/db mtHsp70 mice as compared to db/db (Figures 5C, E-F). Complex III showed no differences (Figure 5D).

Figure 5. Mitochondrial respiration and electron transport chain complex activities during type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Mitochondrial (A) state 3 and (B) state 4 respiration rates in SSM from mtHsp70 db/db and db/db mice. ETC complex activities in SSM from mtHsp70 db/db and db/db mice in (C) complex I, (D) complex III, (E) complex IV, (F) and ATP synthase. Control (n = 6), db/db (n = 5), mtHsp70 (n = 5), and mtHsp70 db/db (n = 5) for both SSM and IFM mitochondrial respiration and electron transport chain complex activities. Values are expressed as means ± SEM. Solid line = control levels (average value of measurements); T2DM = type 2 diabetes mellitus; CI = complex I; CIII = complex III, CIV = complex IV. *P ≤ 0.05 for control vs. T2DM. #P ≤ 0.05 for T2DM vs. mtHsp70 T2DM.

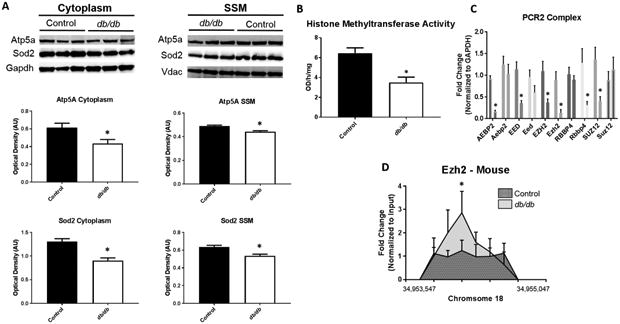

Mechanisms of Protein Import and Global Epigenomics

Mechanisms controlling the observed dysfunction in the mitochondrial protein import pathway are important to understand. The proteomic analyses revealed changes in mitochondrial proteins comprising the electron transport chain complexes. Atp5a and Sod2 were measured in the cytoplasm and SSM, confirming the decreased expression observed in the SSM but also revealing the lack of protein to be transported across the mitochondrial membrane found in the cytoplasm during diabetes (Figure 6A). It is unclear why this occurred as numerous factors can influence protein make-up in cellular compartments including protein degradation [38, 39]. Further, global epigenetics of the histone modification H3K27me3 were measured through an activity assay of nuclear fractions (Figure 6B) and through qPCR of the polycomb repressive complex 2 (PCR2) (Figure 6C). Transcript expression was shown to decrease for most of the PCR2 members, with the catalytic subunit of the complex, Enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2), showing significant reduction in both the human and mouse (Figure 6C). These indices demonstrated a global decrease in the repressive histone mark H3K27me3, though, when specifically examining the Hspa9 promoter, Ezh2, the catalytic constituent of PCR2 was found to be bound at a higher rate in the diabetic (Figure 6D). Ezh2 binding suggests that epigenetics could play a major role in controlling Hspa9 expression in diabetes.

Figure 6. Mechanisms affecting Protein Import.

Proteomic analyses revealed changes in the abundance of nuclear-encoded mitochondrial proteins in the mitochondrion following diabetes. (A) Examination of protein import mechanisms for both Atp5a and Sod2 through measurement of cytoplasmic and SSM protein content in control (n = 7) and db/db (n = 5) mouse whole heart. To begin to understand epigenetic consequences (B) global histone methyltransferase activity for H3K27me3 was assessed in control (n = 5) and db/db (n = 5) mouse whole heart. Further, (C) constituents of the PCR2 complex were measured through qPCR in both human (ND and T2DM, n = 5) and mouse (control and db/db, n = 5) cardiac tissue. At the Hspa9 promoter loci, (D) ChIP pulldown and qPCR was performed for Ezh2. Values are expressed as means ± SEM. *P ≤ 0.05 for control vs. diabetes mellitus. ChIP-qPCR samples were normalized to their respective input control. GAPDH was used to normalize PCR2 components. H3K27me3 = histone 3 lysine 27 tri-methylation, PCR2 = Polycomb Repressive Complex 2, HSPA9 = Heat Shock Protein Family A (Hsp70) Member 9, AEBP2 = AE Binding Protein 2, EED = Embryonic Ectoderm Development, EZH2 = Enhancer of zeste homolog 2, RBBP4 = RB Binding Protein 4, SUZ12 = Suppressor of Zeste 12 Homolog T2DM = type 2 diabetes mellitus.

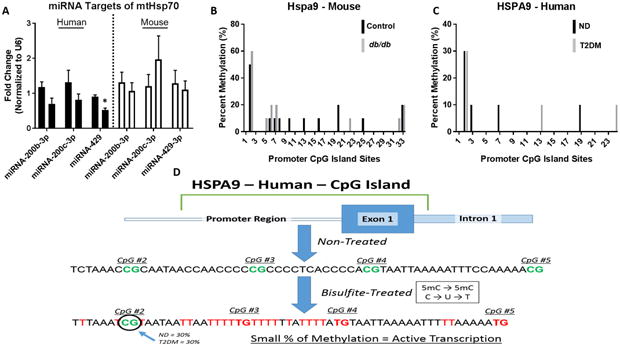

miRNA Expression Levels and CpG Island Methylation

Analysis of miRNAs which are predicted to bind both the human HSPA9 and mouse Hspa9 mRNA transcripts revealed insignificant contribution to mtHsp70 downregulation (Figure 7A). Assessment of methylation at CpG islands within the promoter region of HSPA9 and Hspa9 revealed that while some meylation did occur, total methylation of genomic loci were similar between the control and diabetic groups in both mouse (Figure 7B) and human (Figure 7C). Transcription of the HSPA9 and Hspa9 genes are unlikely to be halted by amount of DNA methylation present both in the control and diabetic groups, with research suggesting >80% of CpG methylation at a specific CpG island is required to significantly abate gene expression [40, 41]. As an illustration (Figure 7D), the CpG sites located at the 2nd, 3rd, 4th, and 5th region in Figure 6C were used to relate the limited methylation of the human HSPA9 promoter region.

Figure 7. MiRNA targets and CpG island methylation for HSPA9 and Hspa9.

(A) ND (left, n = 6) versus T2DM (right, n = 6) miRNA expression levels predicted to target HSPA9 in human patient right atrial tissue (black bars) and control (left, n = 6) versus db/db (right, n = 6) miRNA expression levels predicted to target Hspa9 in mice whole heart (white bars). (B) CpG island methylation in the promotor region of Hspa9 in control (black, n = 6) versus db/db (grey, n = 6) mice. (C) CpG island methylation in the promotor region of HSPA9 in non-diabetic (black, n = 6) versus type 2 diabetic (grey, n = 6) human patient samples. For both human and mouse CpG methylation, 10 clones were selected from each group. (D) An overview of the process for measuring and analyzing CpG island methylation at the HSPA9 promoter region, revealing limited methylation in both the control and diabetic cohort. Values are expressed as means ± SEM; *P ≤ 0.05 for control vs. T2DM. MiRNA analyses were normalized to U6. HSPA9 = Heat Shock Protein Family A (Hsp70) Member 9, ND = non-diabetic, T2DM = type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Histone Profiles and PCR2 Complexes

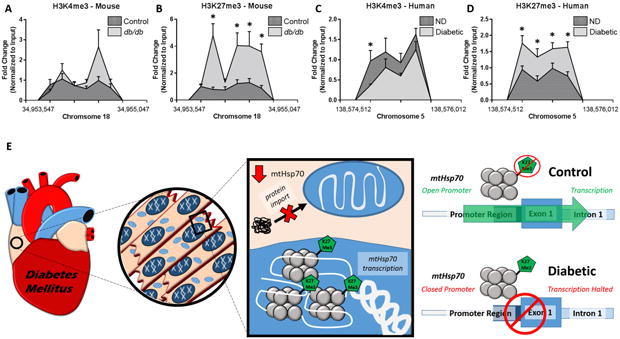

Assessment of the histone activation mark H3K4me3 on chromosome 18 in the mouse and chromosome 5 in the human in both non-diabetic and type 2 diabetic samples revealed few changes (Figure 8A, C), while significant alterations were found in the repressive mark, H3K27me3, in both models of disease (Figure 8B, D). These data suggest that the H3K27me3 is localized more highly to HSPA9 and Hspa9 during diabetic insult, leading to a repression in transcription/translation (Figure 8B, D). A graphical depiction of how the how histone methylation can affect transcription is provided (Figure 8E). In the diabetic heart, mtHsp70 expression and mitochondrial protein import could be negatively impacted by targeted histone modifications at the HSPA9 promoter loci.

Figure 8. Changes in histone methylation dynamics for HSPA9 and Hspa9.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)-qPCR was used to evaluate histone methylation status at the promoter region of Hspa9 and HSPA9. Histone peaks were assessed at the mouse Hspa9 promoter for (A) H3K4me3 (n = 6) and (B) H3K27me3 (n = 6) and at the human HSPA9 promoter for (C) H3K4me3 (n = 6) and (D) H3K27me3 (n = 6). (E) An overview of the experimental findings and the proposed hypothesis. Functional changes in the diabetic heart can be attributed, in part, to decreased transcription of mtHsp70 through epigenetic regulation, ultimately limiting protein import into the mitochondrion. Values are expressed as means ± SEM. *P ≤ 0.05 for control vs. diabetes mellitus. ChIP-qPCR samples were normalized to their respective input control. H3K4me3 = histone 3 lysine 4 tri-methylation, H3K27me3 = histone 3 lysine 27 tri-methylation, ND = non-diabetic, T2DM = type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Discussion

Mitochondria are essential for a variety of cellular processes including energy metabolism, ATP synthesis and regulation of redox balance, all of which depend on nuclear-encoded mitochondrial proteins. Since the nucleus encodes for the vast majority of proteins in the mitochondrion (>99%), a complex protein translocation mechanism is required for directing proteins to specific mitochondrial subcompartments and proper mitochondrial function [42]. In the current study, we hypothesized that decrements in nuclear-encoded mitochondrial protein import following diabetic insult were due in part, to decreased mtHsp70 content [13, 23]. Our results revealed decrements of protein import at all time intervals (30 seconds, 1 and 2 minutes of MitoGFP1 expression) in db/db SSM, which was rectified by overexpression of mtHsp70.

An important implication for nuclear-encoded mitochondrial protein import is its impact on mitochondrial proteome signature. Proteomic analyses have revealed alterations in mitochondrial functional processes such as oxidative phosphorylation and ATP synthesis, which are correlated with decrements in nuclear-encoded mitochondrial protein import [17, 23, 43-46]. Among the proteins decreased in SSM of both animal and human patient models following type 2 diabetic insult is mtHsp70 [13, 14]. MtHsp70 overexpression restored a number of proteins involved in electron transport function, fatty acid metabolism, and the transporter protein Slc25a3 following type 2 diabetic insult. Proteomic surveys suggest that approximately 67% of mitochondrial proteins reside in the mitochondrial matrix, followed by 21% located within the inner mitochondrial membrane, and 6% and 4% residing in the inner membrane space and outer mitochondrial membrane, respectively [47, 48]. In the current study, inner mitochondrial membrane and matrix proteins were the most predominantly affected mitochondrial subcompartments in terms of proteomic alterations, with mtHsp70 overexpression exerting the greatest targeted restoration within these locales. This was particularly relevant for the inner mitochondria membrane which displayed the largest benefit in terms of protein restoration from mtHsp70 overexpression.

Enhanced mitochondrial function was associated with preservation of LV pump function as reflected by restoration of EF and FS, along with volume and diametric changes during systole in db/db mice following mtHsp70 overexpression. Speckle-tracking based strain analyses evaluating global and regional LS and LSR, provided complementary evidence of LV pump function restoration through mtHsp70 overexpression. Literature suggests that LS provides a good correlation to LV EF, a measure that is decreased during type 2 diabetes mellitus [13, 20, 49, 50]. It is interesting to note that though the primary benefit of mtHsp70 overexpression occurred to SSM, ATP production from each mitochondrial subpopulation is likely critical for efficient cardiac contractile function, indicating that both may play a role in preserving cardiac function during pathological states. Further, an interconnected mitochondrial network through a mitochondrial reticulum could provide a pathway for energy distribution within the cardiomyocyte [51, 52].

The mtHsp70 gene contains both a CpG island and known histone binding regions at its promoter, inferring the capacity to be epigenetically regulated under changing cellular environments. Our data indicate that localization of H3K27me3 was increased during type 2 diabetic insult. H3K27me3 is known to silence gene expression, but the presence or absence of coinciding DNA methylation is cell and development dependent [53, 54]. The increased expression of H3K27me3 localization at mtHSP70 suggests an epigenetic mechanism of regulation during type 2 diabetes mellitus, which could be attributed to the increased presence of fatty acids [55], or other cellular dynamics disrupted during pathological development. Further, H3K27me3 marks are associated with PCR2 activity [7], which displayed decreased expression during type 2 diabetic insult. The decrease in PCR2 expression suggests that global H3K27me3 is not the cause of the increased association at the HSPA9 and Hspa9 loci, but rather a selective mechanism. The selective mechanism would have to be specific to the genomic location, potentially a pri-miRNA tether for recruiting PCR2 constituents [56].

The epigenetic regulation of mtHsp70 may speak to a larger picture of how nuclear-encoded mitochondrial proteins are regulated. The control of mitochondrial bioenergetics during diabetes mellitus, through histone modifications or DNA methylation of nuclear-encoded mitochondrial proteins, could be implemented by the cell either as a result of the pathology, or an attempt to preserve further functional breakdown. Our study provides evidence for the importance of the nuclear/mitochondrial crosstalk in regulating mitochondrial function and energetics, depicting a mechanistic means for controlling mtHsp70 expression during type 2 diabetes mellitus. As a future perspective, miRNAs have been shown in the cardiovascular system to regulate histone modifications [57] and should be further examined as an additional method of gene regulation.

In previous reports, and further justified by the current research, is the dichotomy that appears to exist between subpopulations of mitochondria being differentially impacted under varying conditions of diabetic insult; the IFM being detrimentally impaired in type 1 diabetes and the SSM exhibiting dysfunction in type 2 diabetes [4, 13, 35]. In conclusion our data reveal for the first time, several key findings: 1) disruption of mitochondrial proteomic signature in type 2 diabetic SSM is linked to an inability to efficiently import nuclear-encoded mitochondrial proteins; 2) overexpression of mtHsp70 levels provides restoration of mitochondrial function, protein import efficiency and ultimately proteomic signature; and 3) increased expression of H3K27me3 localization at mtHSP70 during type 2 diabetes mellitus suggests an epigenetic mechanism of regulation. Taken together, these findings suggest that restoration of a key import constituent of the active protein import motor provides therapeutic benefit to mitochondrial proteome signature, highlighting the critical role of this mitochondrial process during type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Type 2 diabetes mellitus is associated with mitochondrial proteome dysregulation.

Type 2 diabetes mellitus decreases mitochondrial protein import via loss of mtHsp70.

Loss of mtHsp70 occurs through epigenetic dysregulation at its nuclear locus.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute grant HL128485 and the WVU CTSI grant U54GM104942 awarded to JMH. This work was supported by an American Heart Association Predoctoral Fellowship grant AHA 14PRE19890020 awarded to DLS This work was supported by a National Science Foundation IGERT: Research and Education in Nanotoxicology at West Virginia University Fellowship grant 1144676 awarded to QAH. This work was supported by an American Heart Association Predoctoral Fellowship (AHA 17PRE33660333) awarded to QAH. This work was supported by an American Heart Association Predoctoral Fellowship grant AHA 13PRE16850066 awarded to CEN. Flow Cytometry analyses were performed by the WVU Flow Cytometry & Single Cell Core and supported by P30 GM103488 and S10 OD016165. Ingenuity Pathway Analyses were supported by WV INBRE Grant P20 GM103434. Proteomic analyses were performed in conjunction with Protea Biosciences.

Footnotes

Author's contributions: D.L.S., Q.A.H., C.E.N., K.M.H., A.J.D., M.V.P., S.M.S. researched data. D.L.S., Q.A.H., J.M.H. performed statistical analyses. D.L.S. and Q.A.H. wrote the manuscript. D.L.S., Q.A.H., C.E.N., K.M.H., A.J.D., M.V.P., A.K., S.M.S., J.M.H. reviewed/edited manuscript. D.L.S., Q.A.H., J.M.H. contributed to discussion.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Anderson S, Bankier AT, Barrell BG, de Bruijn MH, Coulson AR, Drouin J, Eperon IC, Nierlich DP, Roe BA, Sanger F, et al. Sequence and organization of the human mitochondrial genome. Nature. 1981;290(5806):457–465. doi: 10.1038/290457a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Calvo S, Jain M, Xie X, Sheth SA, Chang B, Goldberger OA, Spinazzola A, Zeviani M, Carr SA, Mootha VK. Systematic identification of human mitochondrial disease genes through integrative genomics. Nature genetics. 2006;38(5):576–582. doi: 10.1038/ng1776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perocchi F, Jensen LJ, Gagneur J, Ahting U, von Mering C, Bork P, Prokisch H, Steinmetz LM. Assessing systems properties of yeast mitochondria through an interaction map of the organelle. PLoS genetics. 2006;2(10):e170. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baseler WA, Croston TL, Hollander JM. Functional Characteristics of Mortalin. In: Kaul SC, Wadhwa R, editors. Mortalin Biology: Life, Stress and Death. New York: Springer; 2012. pp. 55–80. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williamson CL, Dabkowski ER, Dillmann WH, Hollander JM. Mitochondria protection from hypoxia/reoxygenation injury with mitochondria heat shock protein 70 overexpression. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;294(1):H249–256. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00775.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bannister AJ, Kouzarides T. Regulation of chromatin by histone modifications. Cell Res. 2011;21(3):381–395. doi: 10.1038/cr.2011.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schwartz YB, Pirrotta V. A new world of Polycombs: unexpected partnerships and emerging functions. Nat Rev Genet. 2013;14(12):853–864. doi: 10.1038/nrg3603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jin B, Robertson KD. DNA methyltransferases, DNA damage repair, and cancer. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2013;754:3–29. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-9967-2_1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhao J, Goldberg J, Bremner JD, Vaccarino V. Global DNA methylation is associated with insulin resistance: a monozygotic twin study. Diabetes. 2012;61(2):542–546. doi: 10.2337/db11-1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wahl S, Drong A, Lehne B, Loh M, Scott WR, Kunze S, Tsai PC, Ried JS, Zhang W, Yang Y, et al. Epigenome-wide association study of body mass index, and the adverse outcomes of adiposity. Nature. 2017;541(7635):81–86. doi: 10.1038/nature20784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jufvas A, Sjodin S, Lundqvist K, Amin R, Vener AV, Stralfors P. Global differences in specific histone H3 methylation are associated with overweight and type 2 diabetes. Clin Epigenetics. 2013;5(1):15. doi: 10.1186/1868-7083-5-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Akkers RC, van Heeringen SJ, Jacobi UG, Janssen-Megens EM, Francoijs KJ, Stunnenberg HG, Veenstra GJ. A hierarchy of H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 acquisition in spatial gene regulation in Xenopus embryos. Dev Cell. 2009;17(3):425–434. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dabkowski ER, Baseler WA, Williamson CL, Powell M, Razunguzwa TT, Frisbee JC, Hollander JM. Mitochondrial dysfunction in the type 2 diabetic heart is associated with alterations in spatially distinct mitochondrial proteomes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;299(2):H529–540. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00267.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Croston TL, Thapa D, Holden AA, Tveter KJ, Lewis SE, Shepherd DL, Nichols CE, Long DM, Olfert IM, Jagannathan R, et al. Functional deficiencies of subsarcolemmal mitochondria in the type 2 diabetic human heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2014;307(1):H54–65. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00845.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weinhouse C. Mitochondrial-epigenetic crosstalk in environmental toxicology. Toxicology. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2017.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gulick J, Subramaniam A, Neumann J, Robbins J. Isolation and characterization of the mouse cardiac myosin heavy chain genes. J Biol Chem. 1991;266(14):9180–9185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baseler WA, Dabkowski ER, Jagannathan R, Thapa D, Nichols CE, Shepherd DL, Croston TL, Powell M, Razunguzwa TT, Lewis SE, et al. Reversal of mitochondrial proteomic loss in Type 1 diabetic heart with overexpression of phospholipid hydroperoxide glutathione peroxidase. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2013;304(7):R553–565. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00249.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dabkowski ER, Williamson CL, Hollander JM. Mitochondria-specific transgenic overexpression of phospholipid hydroperoxide glutathione peroxidase (GPx4) attenuates ischemia/reperfusion-associated cardiac dysfunction. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;45(6):855–865. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thapa D, Nichols CE, Lewis SE, Shepherd DL, Jagannathan R, Croston TL, Tveter KJ, Holden AA, Baseler WA, Hollander JM. Transgenic overexpression of mitofilin attenuates diabetes mellitus-associated cardiac and mitochondria dysfunction. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2015;79:212–223. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2014.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shepherd DL, Nichols CE, Croston TL, McLaughlin SL, Petrone AB, Lewis SE, Thapa D, Long DM, Dick GM, Hollander JM. Early detection of cardiac dysfunction in the type 1 diabetic heart using speckle-tracking based strain imaging. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2016;90:74–83. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2015.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nichols CE, Shepherd DL, Knuckles TL, Thapa D, Stricker JC, Stapleton PA, Minarchick VC, Erdely A, Zeidler-Erdely PC, Alway SE, et al. Cardiac and mitochondrial dysfunction following acute pulmonary exposure to mountaintop removal mining particulate matter. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2015;309(12):H2017–2030. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00353.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Palmer JW, Tandler B, Hoppel CL. Biochemical properties of subsarcolemmal and interfibrillar mitochondria isolated from rat cardiac muscle. J Biol Chem. 1977;252(23):8731–8739. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baseler WA, Dabkowski ER, Williamson CL, Croston TL, Thapa D, Powell MJ, Razunguzwa TT, Hollander JM. Proteomic alterations of distinct mitochondrial subpopulations in the type 1 diabetic heart: contribution of protein import dysfunction. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2011;300(2):R186–200. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00423.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Croston TL, Shepherd DL, Thapa D, Nichols CE, Lewis SE, Dabkowski ER, Jagannathan R, Baseler WA, Hollander JM. Evaluation of the cardiolipin biosynthetic pathway and its interactions in the diabetic heart. Life sciences. 2013;93(8):313–322. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2013.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dabkowski ER, Williamson CL, Bukowski VC, Chapman RS, Leonard SS, Peer CJ, Callery PS, Hollander JM. Diabetic cardiomyopathy-associated dysfunction in spatially distinct mitochondrial subpopulations. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;296(2):H359–369. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00467.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1006/abio.1976.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stojanovski D, Pfanner N, Wiedemann N. Import of proteins into mitochondria. Methods in cell biology. 2007;80:783–806. doi: 10.1016/S0091-679X(06)80036-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ritov VB, Menshikova EV, He J, Ferrell RE, Goodpaster BH, Kelley DE. Deficiency of subsarcolemmal mitochondria in obesity and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2005;54(1):8–14. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pullman ME, Penefsky HS, Datta A, Racker E. Partial resolution of the enzymes catalyzing oxidative phosphorylation. I. Purification and properties of soluble dinitrophenol-stimulated adenosine triphosphatase. J Biol Chem. 1960;235:3322–3329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Feniouk BA, Suzuki T, Yoshida M. Regulatory interplay between proton motive force, ADP, phosphate, and subunit epsilon in bacterial ATP synthase. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(1):764–772. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606321200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chance B, Williams GR. Respiratory enzymes in oxidative phosphorylation. I. Kinetics of oxygen utilization. J Biol Chem. 1955;217(1):383–393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chance B, Williams GR. Respiratory enzymes in oxidative phosphorylation. VI. The effects of adenosine diphosphate on azide-treated mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 1956;221(1):477–489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227(5259):680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Williamson CL, Dabkowski ER, Baseler WA, Croston TL, Alway SE, Hollander JM. Enhanced apoptotic propensity in diabetic cardiac mitochondria: influence of subcellular spatial location. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;298(2):H633–642. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00668.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jagannathan R, Thapa D, Nichols CE, Shepherd DL, Stricker JC, Croston TL, Baseler WA, Lewis SE, Martinez I, Hollander JM. Translational Regulation of the Mitochondrial Genome Following Redistribution of Mitochondrial MicroRNA in the Diabetic Heart. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2015;8(6):785–802. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.115.001067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang X. Improving microRNA target prediction by modeling with unambiguously identified microRNA-target pairs from CLIP-ligation studies. Bioinformatics. 2016;32(9):1316–1322. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wong N, Wang X. miRDB: an online resource for microRNA target prediction and functional annotations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(Database issue):D146–152. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zu L, Bedja D, Fox-Talbot K, Gabrielson KL, Van Kaer L, Becker LC, Cai ZP. Evidence for a role of immunoproteasomes in regulating cardiac muscle mass in diabetic mice. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2010;49(1):5–15. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang X, Hu Z, Hu J, Du J, Mitch WE. Insulin resistance accelerates muscle protein degradation: Activation of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway by defects in muscle cell signaling. Endocrinology. 2006;147(9):4160–4168. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ehrlich M. DNA methylation in cancer: too much, but also too little. Oncogene. 2002;21(35):5400–5413. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Illingworth RS, Bird AP. CpG islands--‘a rough guide’. FEBS Lett. 2009;583(11):1713–1720. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chacinska A, Koehler CM, Milenkovic D, Lithgow T, Pfanner N. Importing mitochondrial proteins: machineries and mechanisms. Cell. 2009;138(4):628–644. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bugger H, Chen D, Riehle C, Soto J, Theobald HA, Hu XX, Ganesan B, Weimer BC, Abel ED. Tissue-specific remodeling of the mitochondrial proteome in type 1 diabetic akita mice. Diabetes. 2009;58(9):1986–1997. doi: 10.2337/db09-0259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hamblin M, Friedman DB, Hill S, Caprioli RM, Smith HM, Hill MF. Alterations in the diabetic myocardial proteome coupled with increased myocardial oxidative stress underlies diabetic cardiomyopathy. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2007;42(4):884–895. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shen X, Zheng S, Thongboonkerd V, Xu M, Pierce WM, Jr, Klein JB, Epstein PN. Cardiac mitochondrial damage and biogenesis in a chronic model of type 1 diabetes. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2004;287(5):E896–905. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00047.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Turko IV, Murad F. Quantitative protein profiling in heart mitochondria from diabetic rats. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(37):35844–35849. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303139200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Distler AM, Kerner J, Hoppel CL. Proteomics of mitochondrial inner and outer membranes. Proteomics. 2008;8(19):4066–4082. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200800102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schnaitman C, Greenawalt JW. Enzymatic properties of the inner and outer membranes of rat liver mitochondria. J Cell Biol. 1968;38(1):158–175. doi: 10.1083/jcb.38.1.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brown J, Jenkins C, Marwick TH. Use of myocardial strain to assess global left ventricular function: a comparison with cardiac magnetic resonance and 3-dimensional echocardiography. Am Heart J. 2009;157(1):102.e101–105. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Choi JO, Shin DH, Cho SW, Song YB, Kim JH, Kim YG, Lee SC, Park SW. Effect of preload on left ventricular longitudinal strain by 2D speckle tracking. Echocardiography. 2008;25(8):873–879. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8175.2008.00707.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Glancy B, Hartnell LM, Malide D, Yu ZX, Combs CA, Connelly PS, Subramaniam S, Balaban RS. Mitochondrial reticulum for cellular energy distribution in muscle. Nature. 2015;523(7562):617–620. doi: 10.1038/nature14614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Skulachev VP. Power transmission along biological membranes. J Membr Biol. 1990;114(2):97–112. doi: 10.1007/BF01869092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Inoue A, Jiang L, Lu F, Suzuki T, Zhang Y. Maternal H3K27me3 controls DNA methylation-independent imprinting. Nature. 2017;547(7664):419–424. doi: 10.1038/nature23262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hagarman JA, Motley MP, Kristjansdottir K, Soloway PD. Coordinate regulation of DNA methylation and H3K27me3 in mouse embryonic stem cells. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e53880. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kumar S, Pamulapati H, Tikoo K. Fatty acid induced metabolic memory involves alterations in renal histone H3K36me2 and H3K27me3. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2016;422:233–242. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2015.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mathiyalagan P, Okabe J, Chang L, Su Y, Du XJ, El-Osta A. The primary microRNA-208b interacts with Polycomb-group protein, Ezh2, to regulate gene expression in the heart. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(2):790–803. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hathaway QA, Pinti MV, Durr AJ, Waris S, Shepherd DL, Hollander JM. Regulating MicroRNA Expression: At the Heart of Diabetes Mellitus and the Mitochondrion. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2017 doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00520.2017. ajpheart 00520 02017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.