Abstract

Context

Community-based clergy are highly engaged in helping terminally ill patients address spiritual concerns at the end of life (EOL). Despite playing a central role in EOL care, clergy report feeling ill-equipped to spiritually support patients in this context. Significant gaps exist in understanding how clergy beliefs and practices influence EOL care.

Objectives

The objective of this study was to propose a conceptual framework to guide EOL educational programming for community-based clergy.

Methods

This was a qualitative, descriptive study. Clergy from varying spiritual backgrounds, geographical locations in the U.S., and race/ethnicities were recruited and asked about optimal spiritual care provided to patients at the EOL. Interviews were audio taped, transcribed, and analyzed following principles of grounded theory. A final set of themes and subthemes were identified through an iterative process of constant comparison. Participants also completed a survey regarding experiences ministering to the terminally ill.

Results

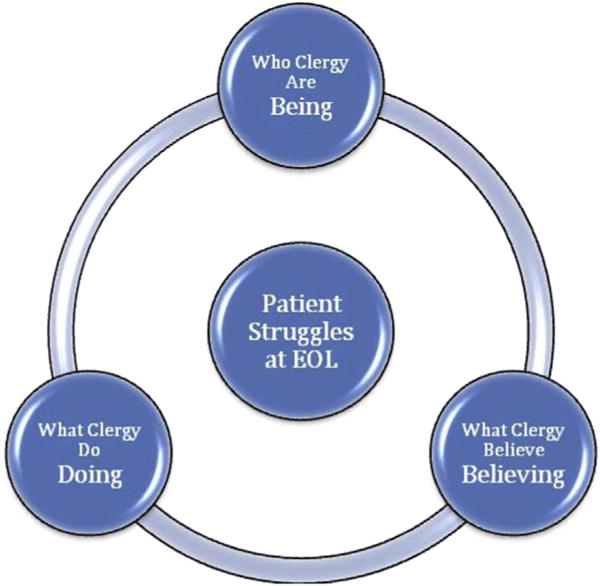

A total of 35 clergy participated in 14 individual interviews and two focus groups. Primary themes included Patient Struggles at EOL and Clergy Professional Identity in Ministering to the Terminally Ill. Patient Struggles at EOL focused on existential questions, practical concerns, and difficult emotions. Clergy Professional Identity in Ministering to the Terminally Ill was characterized by descriptions of Who Clergy Are (“Being”), What Clergy Do (“Doing”), and What Clergy Believe (“Believing”). “Being” was reflected primarily by manifestations of presence; “Doing” by subthemes of religious activities, spiritual support, meeting practical needs, and mistakes to avoid; “Believing” by subthemes of having a relationship with God, nurturing virtues, and eternal life. Survey results were congruent with interview and focus group findings.

Conclusion

A conceptual framework informed by clergy perspectives of optimal spiritual care can guide EOL educational programming for clergy.

Keywords: Religion, spirituality, spiritual care, end of life, clergy, palliative care, education

Introduction

Spiritual concerns are particularly pressing at the end of life (EOL),1 and roughly half of all terminally ill patients in the U.S. rely on community-based clergy for spiritual support.2 Clergy spend an average of 3–4 hours per week visiting the ill3 and are especially important in meeting the spiritual needs of minority patients.4 Despite their central role in ministering to terminally ill patients,5,6 most clergy report inadequate knowledge regarding EOL care and a desire for more EOL training.7–9 This lack of knowledge regarding EOL care among community-based clergy is an issue of critical importance, given recent data that show patients who receive significant community spiritual support are less likely to use hospice and more likely to receive intensive medical care near death.10

In essence, community-based clergy—who provide the most spiritual support to patients at EOL11,12 and can have a dramatic impact on the patient’s death experience—receive minimal, if any, EOL training. Also, little is known about actual clergy practices and goals in counseling patients at EOL. This study aims to address these gaps by 1) exploring clergy perspectives on optimal spiritual care provided to terminally ill patients and 2) using these findings to inform a conceptual framework for clergy EOL education. This study is part of the larger National Cancer Institute-funded “National Clergy Project on End-of-Life Care,” a mixed-methods study examining clergy beliefs and practices in providing EOL spiritual care in the U.S.

Methods

Sample

Methods for the study have been previously reported.13 In brief, this study used interviews, focus groups, and surveys to describe community clergy experiences with EOL care and their perceptions of optimal spiritual care. We sought to recruit a sample representative of U.S. clergy (not the general population) demographics, and we oversampled from minority clergy to capture a diverse range of perspectives. A key informant with access to local community clergy, in consultation with M. J. B., recruited clergy leaders currently serving in a community congregation based on preselected criteria including race/ethnicity, congregational size, and denomination. Thirty-five clergy were interviewed in one-on-one interviews (n = 14) and two focus groups (with a total of 21 participants) within five U.S. states (California, Illinois, Massachusetts, New York, and Texas). All participants provided informed consent per protocols approved by the Harvard/Dana-Farber Cancer Center Institutional Review Board.

Protocol

Clergy were enrolled between November 2013 and September 2014. An interdisciplinary panel of medical educators and religion experts developed a semistructured interview guide to explore clergy perspectives regarding EOL care. Relevant to this report, clergy were asked the following open-ended questions from the interview guide: “When you care for patients who may be facing death, such as terminal cancer, how should a minister in a congregation provide spiritual care? What does spiritual care ideally look like in your opinion and experience?” Research staff underwent a half-day training session in interview methods and received ongoing supervisory guidance from M. J. B., to ensure homogeneous interview procedures. Interviews and focus groups were conducted in English or Spanish (n = 2) and ranged between 45 and 120 minutes in duration. Participants received a $25 gift card as a token of appreciation for their participation.

Quantitative Measures

Before the interview or focus group, participants completed a survey assessing age, race, gender, educational level, denominational affiliation, prior EOL training, and experiences in ministering to the terminally ill. As part of the survey, participants were asked to recall the most recent incident in which they provided spiritual care to a dying individual and to describe the length of the patient-clergy relationship, the types of spiritual care provided to the patient, and the timing of death relative to the survey.

Analytical Procedures

Interviews were audio taped, transcribed, translated, and verified if in Spanish, and participants were deidentified. Following principles of grounded theory,14 transcripts were reviewed by R. Q. and C. N., and an initial set of subtheme categories along with corresponding coding frequencies was generated. Subtheme categories were then refined after further independent review of the transcripts by additional members of the research team, and a broader set of conceptual codes (themes) was created during an interactive data analysis session representing the interdisciplinary perspectives of nursing (V. T. L.), psychology (C. N.), and theology (M. J. B., R. Q.). After finalizing the coding schema, transcripts were then reanalyzed (NVivo 10; QSR International, Burlington, MA) by R. Q. and C. N., each coding independently based on derived subtheme categories and themes (Kappa = 0.68). Descriptive statistics were used for quantitative items of the participant surveys.

Results

Quantitative

Clergy demographic information and types of spiritual care provided to the most recent patient who died are provided in Table 1. Offering prayer and reading scripture were the most common forms of clergy spiritual care reported; approximately half indicated that they “help [patients] sort through medical decisions.” Of note, 72% of clergy respondents indicated a desire for more EOL training.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics of Clergy Participants and Selected Results From Quantitative Surveys

| Clergy Demographic Information | na | % |

|---|---|---|

| Total participants | 35 | 100 |

| Male gender | 32 | 91.4 |

| Average years serving as clergy (n = 32) | 20 yrs | |

| Geographical location | ||

| Northeast | 11 | 31.4 |

| Southwest | 11 | 31.4 |

| Midwest | 10 | 28.6 |

| West | 3 | 8.6 |

| Race (n = 32) | ||

| White | 16 | 50.0 |

| Black | 14 | 43.7 |

| Asian | 2 | 6.3 |

| Ethnicity (n = 30) | ||

| Latino/Hispanic | 2 | 6.7 |

| Religious tradition (n = 35) | ||

| Protestantb | 27 | 77.1 |

| Roman Catholic | 4 | 11.4 |

| Jewish | 2 | 5.7 |

| Eastern Orthodox | 1 | 2.9 |

| Other (Center for Spiritual Living) | 1 | 2.9 |

| Theological orientation (n = 32) | ||

| Theologically conservativec | 21 | 65.6 |

| Theologically liberal | 11 | 34.4 |

| Educational level (n = 34) | ||

| Below master’s degree | 6 | 17.7 |

| Master’s degree (e.g., MDiv) | 15 | 44.1 |

| Doctoral degree | 13 | 38.2 |

|

| ||

| Educational preparation in EOL care | ||

|

| ||

| Prior receipt of EOL training (n = 31) | 23 | 74.2 |

| Type of training received (n = 23) | ||

| Clinical Pastoral Education | 13 | 56.5 |

| Seminary course | 13 | 56.5 |

| One-on-one mentorship | 9 | 39.1 |

| Book | 9 | 39.1 |

| Desire future EOL training (n = 29) | 21 | 72.4 |

|

| ||

| Most recent patient visited by clergy who died from illness | ||

|

| ||

| Length of time between patient’s death and survey (n = 19) | ||

| Less than 3 months | 10 | 52.6 |

| 3–6 months | 3 | 15.8 |

| 6–12 months | 2 | 10.5 |

| 1–2 yrs | 4 | 21.0 |

| Length of time clergy knew patient (n =29) | ||

| Less than 6 months | 5 | 17.2 |

| About a year | 2 | 7.1 |

| 1–2 yrs | 4 | 13.8 |

| 3 yrs or more | 18 | 62.0 |

| Types of spiritual care provided (n = 28) | ||

| Who clergy are (“Being”) | ||

| Express compassion | 22 | 78.6 |

| Listen to spiritual concerns | 15 | 53.6 |

| What clergy do (“Doing”) | ||

| Pray | 26 | 92.9 |

| Read scripture | 23 | 82.1 |

| Offer a religious ritual (e.g., communion) | 15 | 53.6 |

| Help sort through medical decisions | 13 | 46.4 |

| What clergy believe (“Believing”) | ||

| Talk about death or an afterlife | 15 | 53.6 |

| Talk about sources of peace | 13 | 46.4 |

| Talk about forgiveness | 8 | 28.6 |

| Talk about sources of meaning | 7 | 25.0 |

| Otherd | 7 | 25.0 |

EOL = end of life.

Not all participants responded to every question; therefore, “n” may not total 35.

Protestant clergy identified with the following Protestant denominations: Assemblies of God (2) Baptist (5), Congregational (4), Episcopalian (1), Methodist (3), Nondenominational (6), Presbyterian (1), and Seventh-Day Adventist (1). Four Protestant clergy did not disclose specific denominational information.

Clergy were categorized as “theologically conservative” if they agreed with the following statement: “My religious tradition’s Holy Book is perfect because it is the Word of God.”

“Other” included: Interfacing with family (n = 5) including conflict, reconciliation, and presence; provide comfort in personal area of faith (n = 1); and providing life review with patient (n = 1).

Qualitative Themes

In describing their perspectives regarding optimal spiritual care for terminally ill patients, clergy responses focused on two primary, interrelated themes: the challenging spiritual and temporal struggles faced by terminally ill patients and their family caregivers, and the ways in which clergy professional identity helps congregants navigate these struggles at the EOL (Table 2). The primary theme of “Patient Struggles at EOL” highlighted commonly encountered existential questions— many of which were spiritual/religious in nature-—as well as practical/temporal concerns and difficult emotions related to terminal illness. The primary theme of “Clergy Professional Identity in Ministering to the Terminally Ill” was characterized by descriptions of Who Clergy Are (“Being”), What Clergy Do (“Doing”), and What Clergy Believe (“Believing”). “Being” was supported by subthemes related to various manifestations of Presence; “Doing” by subthemes of religious activities, spiritual support, meeting the needs of patient/families, and mistakes to avoid; and “Believing” by subthemes of having a relationship with God, nurturing virtues, and eternal life.

Table 2.

Summary of Primary Themes

| Primary Theme I: Common Patient Struggles at the End of Life |

|---|

| Existential questions |

| Did I waste my time? Did I live a good life? Why is this happening to my family member? Why do I remain sick and not healed? |

| Practical and temporal concerns |

| Leaving loved ones behind without adequate financial or emotional resources; missing important life events; doubts and confusion related to disease and treatment decisions; fractured relationships |

| Difficult emotions |

| Anger, frustration, anxiety, blame, despair, fear, sadness, depression, regret, denial |

|

|

| Primary Theme II: Clergy Professional Identity in Ministering to the Terminally Ill |

|

|

| Who Clergy Are (“Being”) |

| Presence |

| Be available, listen, provide support, guidance, serve as confidante, provide temporary distraction away from illness |

| What Clergy Do (“Doing”) |

| Facilitate religious activities |

| Pray, administer the sacraments, listen to confession, read/interpret scripture, sing/listen to hymns |

| Provide spiritual support |

| Reassure congregants of the love of their Christian community; help patients feel useful/wanted; remind patients they will live on in people’s memories; encourage patients not to waste time or important moments; relieve despair; facilitate reconciliation with others |

| Meet the needs of patient/family caregivers |

| Counsel and support family caregivers; provide personalized care; address cultural beliefs and practices; honor human dignity; encourage legal/emotional/financial preparation for death |

| Mistakes to avoid |

| Misunderstanding that prayer will automatically lead to a cure; focus on religious conversion vs. spiritual needs of patient; too much talking and not enough listening; make patient feel guilty; give unrealistic hope in miracles |

| What Clergy Believe (“Believing”) |

| Having a relationship with God |

| Reconciliation with God; importance of forgiveness; acknowledge different forms of healing; trust in God’s love and His ability to offer strength to help carry burdens; awareness that illness is not punishment |

| Nurturing virtues in illness and dying |

| Hope, love, compassion, acceptance, patience, balance, strength |

| Faith in eternal life |

| Embrace the reality of heaven; knowing peace; theological reassurance of God’s unbreakable love; assurance of salvation after death |

Primary Theme I: Patient Struggles at EOL

Clergy perceived three common struggles that require attention at the EOL for patients and their family caregivers: existential questions, practical and temporal concerns, and difficult emotions (Table 3). Existential questions focused on issues such as “Did I waste my time? Did I live a good life? Why is this happening to my family member? Why do I remain sick and not healed?” A Christian Asian-American minister from China explained:

They normally say “Why me? Why is God letting me walk in this way? I’m still young … Why is God giving me this trial in my life, walking in this path?” So that is always the question in their heart. I think some people receive this question well. Some people not (TC115).

Table 3.

Primary Theme I: Supporting Quotes of Clergy Perceptions of Common Patient Struggles at the End of Lifea

| Existential questions |

| “ … I’ve been praying for it, my friends are praying for it; they’re fasting, they’re asking, heal me, heal me, heal me, and He hasn’t done it. Why not? Why hasn’t He healed me?” So they’re going through that as well. Then what I say is if you look around most people are not healed. There are times in church history when people were, and there were times when they were not; right now that’s just not happening. God is not moving that way. And in a sense you are being healed; this is the way God is choosing to heal you is by bringing you to Him face to face and that’s the best healing. |

| —MB107 |

| Practical and temporal concerns |

| I think there is a sense where you can relieve some of the burden and worry they feel for their family members. So to be able to say “you don’t have to worry about this”. To make sure there is a support system around for them. I think of a guy who is dying and leaving his wife and kids, there are folks around. There is a real helplessness I think you feel for those that are grieving for the ones dying; to relieve them of that, or share that burden with them. |

| —FGMJB416-B |

| Difficult emotions |

| I think some people have regrets that they never healed or repaired damaged relationships, especially with people that are no longer living. People often have profound regrets about past behaviors that they now recognize as having been hurtful or destructive either of themselves or other people. |

| —CG124 |

Participant identifiers that include “FG” indicate that the quote is from a focus group; the letter afterward indicates the specific speaker.

Clergy indicated that practical and temporal concerns encountered by patients at the EOL included issues regarding leaving loved ones behind without adequate financial or emotional support, missing important life events, and doubts and confusion related to disease treatment. A Roman Catholic priest discussed the confusion patients encounter in medical decisions:

I saw this clearly at the cancer center. Somebody is diagnosed with cancer now, okay, let’s talk about the treatment. “What do you mean? How can I think about treatment when I am going to die?” Out of the multiple options for chemotherapy, “Which one do I take? I don’t know, I’m going to die. I can’t make a decision.” So we need to find a way to have these conversations. So we know what is going on earlier than at the end of life (CM1219).

Difficult emotions that characterized patient struggles at the EOL included frustration, anxiety, fear, sadness, blame, despair, depression, regret, denial, and anger. A rabbi explained:

People will tell me up front, when I walk in, they know that I am the rabbi and the first thing they want to do is talk theology with me or talk anger at God or anger from God. I don’t usually have to fish for it (FGMJB416-J).

In some cases, clergy indicated that grappling with these difficult emotions ultimately led patients to accept their situation and helped them to acknowledge that there are no simple answers to these complex issues.

Primary Theme II: Clergy Professional Identity in Ministering to the Terminally Ill: Who We Are, What We Do, and What We Believe

Clergy professional identity was described in terms of three core dimensions: Who Clergy Are (Being), What Clergy Do (Doing), and What Clergy Believe (Believing; Table 4). Providing optimal spiritual care to patients and family members at the EOL necessitated manifestations of all three facets of clergy professional identity working in tandem.

Table 4.

Primary Theme II: Supporting Quotes for Clergy Professional Identify in Ministering to the Terminally Illa

| Who Clergy Are (“Being”) |

|---|

| Presence |

| … as a Catholic priest we’ve got lots in our tool bag. I mean, there are lots of things we can do. And I think what I would encourage the priests that I work with now in my experience, presence is probably the greatest thing; frequent visits. And what we tend to slip into and I’ve even had brother priests say this, “well I anointed them so they don’t need me anymore.” Or, “I gave them communion.” It is like we did our thing and so I’m done. That, I guess I would say from our tradition, we feel those sacraments are great blessings but in a sense they’re only markers for the relationship that should be there certainly with Christ but with his church and with representing the church … To be present is probably the most powerful thing that the sacraments in our faith can work through. |

| —FGMJB416-E |

|

|

| What Clergy Do (“Doing”) |

| Facilitate religious activities |

| I would agree, that presence, being rather than doing, is so important but the physical touch, the holding of one’s hand or even placing your hand on someone’s shoulder, that physical connection, scriptures and particularly the psalms, those familiar passages that you know they are familiar with and that somehow can strengthen and draw them back to that time where the felt most at peace with God. We use music, I don’t sing but I have found that using smart phones as pulling up some YouTube video that has some old hymn of faith that draws them back to that time; that can be extremely powerful. |

| —FGMJB416-A |

| Provide spiritual support |

| Sometime I encourage them to write down their feelings. To be at peace with other people, also. If they are still holding grudges to other people or have enemies, it’s time to make peace. Or forgive or be forgiven. And I also encourage people to write about their life, about their experience; to leave some legacy. And I encourage people to pray. And I will tell them that you are not useless; even you lying in bed in a hospital. You are not useless; you can still serve people and serve God by praying for other people. So I will give them a sense of worthiness. You are still worthy. God gave you life and life is good. The reason why God still gives you life is that you can pray for other people, you can still serve them by praying for others. |

| —TC1030 |

| I would sense that people are a little bit reluctant, even with terminal illnesses, to talk about dying. I will say that, I will bring it up gingerly if I think the situation calls for it and it’s often a relief for the patient to talk about it; to talk about both the process of dying but also the afterlife. I don’t think I’ve created senses of fear or misgivings, or that I made them give up hope by talking about dying. I feel like they’re almost always relieved, they feel better after those conversations. The challenge for me is when to bring it up and I don’t have a magic answer for that, it really depends on the family and the patient. |

| —RT111414 |

| Meet the needs of the patient and family |

| … there is so much focus on the person dying, but in my mind there is so much also with the family that is by the bed, the family that is in the waiting room … there is equal importance in ministering to them because they are the ones that are grieving afterwards and you can really have a profound impact on them and their faith as you are witnessing and ministering to the person who is dying. |

| —FGMJB416-K |

| Mistakes to avoid |

| Trying to preach to somebody who’s dying. Trying to convince somebody to adopt a theological position while they’re dying is unforgivable. The sole role of the clergy at that time is to comfort the family and the person who’s dying. They’re in a state of transition and we’re there to serve them. |

| —RT0819 |

|

|

| What Clergy Believe (“Believing”) |

| Having a relationship with God |

| Then they will ask me are they really saved? Are they in good standing with God? So my part is to confirm their faith and assure them that, yes, you are in good standing with God because you are saved by faith not by works … So as a minister I will walk with them and just hand-holding and assuring them that this life is not the whole part of us. And we still have afterlife and we are certain that we are going back to God. And just assuring them that there is eternal life for us and helping them to seek the balance of seeking treatment and accepting death; especially for terminally ill patients. On the one hand, I will tell them that God can heal you at anytime if he chooses because God is a God of miracles. But on the other hand, this may be the means of God calling you home. There will be an illness that cannot be healed. And that incurable illness is the tool of God calling you home. So, I will tell them to keep on praying, relying on God with peace in their heart, and God is still in control. |

| —TC1030 |

| Nurturing virtues in illness and dying |

| I teach with … pastoral care to H-E-L-P. I let them vent, and in a general sense, give me the History of your anger, when did it start, what were the circumstances around it, Then the E is I let them express the emotion, and I affirm it. And the L is I legitimize that emotion. I don’t blame you for being angry. The same thing, and any person in these circumstances would be angry, because it hurts, it’s painful, it’s uncertain. And then as they vent, and this does take time, we talk about what do we do with that anger; what are the causes, what specifically are you angry at or angry about. Is there room for forgiveness in there? Can you understand why these things are happening and why it’s not necessarily anybody’s fault? And can we get past it and can we get through it? And it’s just forgiveness, it’s this understanding and acceptance, because some time there is no answer, it’s just the way it is, so I accept it. But it’s so much easier said than done …b The “P” is that we work on positive possibilities or possible solutions. The reason for the HELP is to make sure that the person has had plenty of time to communicate their situation in detail and their full emotions. Too many people want to solve the problem right away, so that it becomes about them, their expertise, their brilliance and their success as a counselor. The last thing most people want when they hurt is the quick, magic bullet solution. Not only does it minimize the person’s pain, it gives a false and simple hope. But this is the time to strategize together. My goal here is to inspire real hope and come up with a workable plan … even if it means let’s meet again.… |

| —MB107 |

| Faith in eternal life |

| Being there for them, praying with them, comforting them through whatever decisions they make, encouraging them in that transition from where they are to where we’re promised we’re going, and letting them know that it’s more real. Eternity is more real than the time we spend here. |

| —RT729 |

Participant identifiers that include “FG” indicate that the quote is from a focus group; the letter afterward indicates the specific speaker.

The remaining portion of the quote was provided by the interviewee after the interview was completed by email to allow for clarity and additional elaboration of the clergy member’s idea.

Who Clergy Are (“Being”)

The essence of Who Clergy Are was described primarily as the embodiment of Presence, illustrated by the following statement:

[It is important] with the patients themselves, just to be present. To try to be present, not necessarily offering a whole lot of reasons for anything, but just trying to be present, supportive listening, encouraging. That is a role that the church and the congregation can play in the person’s life who is facing terminal illness (MB129).

Clergy presence involved a commitment to being available to the patient and family, and manifested in listening, providing support and guidance, serving as a confidante, and sometimes helping to shift the focus away from illness (even if just as a temporary distraction).

What Clergy Do (“Doing”)

Clergy’s identity of Doing was described by specific actions deemed spiritually relevant to congregants at the EOL. Key aspects of Doing included religious activities and rituals (prayer, administering the sacraments, listening to confession, reading scripture, singing and listening to hymns), providing spiritual support (reassuring congregants of the love of their faith community, helping patients to feel wanted/useful despite the limitations of serious illness, reminding patients that they will live on in people’s memories, encouraging patients not to waste time or important moments, relieving despair, facilitating reconciliation with others), and meeting the needs of the patient/family (counseling family caregivers, providing personalized care, addressing cultural beliefs/practices, honoring human dignity, and encouraging legal/financial/emotional preparedness for death). These subthemes are illustrated by one Latino pastor who counseled a patient to reconsider other priorities beside cure:

I think that was one of the few times where I had the courage to say “Listen, I also believe in miracles, but hey, don’t waste this opportunity”—and I spoke directly to the man, [who] was the husband and father of the household—and I said, “Listen, you need to speak about the most important things for you in life. What are the things that you want to be remembered? What are the things that you want to share with your family?” (JP414).

An equally important aspect of Doing involved clergy relating what not to do when providing spiritual support to terminally ill patients and family caregivers. Clergy discussed mistakes they regretted in their own ministry, as well as other clergy practices they perceived as unhelpful or even harmful. For example, clergy discussed the potentially negative consequences of focusing on religious conversion at the expense of the individual spiritual needs and desires of the patient, too much talking and not enough listening, making patients feel guilty, and avoiding important discussions related to death and dying. Some also mentioned the mistake of fostering false hope:

I think one mistake is to give them unrealistic hope. Like telling them that you will not die and God will save you …. The fact is people do die and sometimes God wants us to die so that we can return to Him. Another mistake is to really make the patient feel like he or she is lacking faith (TC1030).

What Clergy Believe (“Believing”)

Clergy identity regarding What Clergy Believe focused on substantive religious concerns including having a relationship with God, nurturing key virtues, and being assured of eternal life. Having a relationship with God involved an emphasis on active reconciliation with God, seeking and accepting God’s forgiveness, understanding that healing from God does not always entail physical recovery, knowing God’s love and strength in helping carry burdens, and awareness that illness is not a form of divine punishment. Most clergy considered the patient’s relationship with God as the most important spiritual matter to address. An evangelical pastor said:

Well, the first aspect of spiritual care is providing assurance of their eternal destiny. That question is discussed, clarified, so that they can have that certainty that the biggest issue in human existence is resolved. And I think spiritual care reminds and reinforces that proof (MB107).

Clergy also indicated important virtues for patients to foster within the context of serious illness and dying, including hope, love, compassion, acceptance, patience, balance, and strength. Assurance of eternal life involved clergy encouraging patients to embrace the reality of heaven, the truth of God’s love, and certainty of salvation after death. A Haitian pastor emphasized:

If the person is a Christian, I pray for this person to go in peace. If he’s not a Christian, my desire is for the person to accept Jesus before he dies. If the person is a Christian, I pray, and also tell the person, if the person is conscious and they understand, I say, “Okay, don’t worry too much about what’s going to be left behind or taking care of all these things, so if God calls you, don’t worry. Everything is okay” (MB1021).

Similarly, an Orthodox priest explained:

I have had individuals who are very frightened because they have done terrible things in the course of their life. But again, the teaching is that if you truly regret these things and if you have made a good confession before God, and if you have received the prayers and the forgiveness then, as we say at the end of the confession, “Go in peace and have no further anxiety about the things you have confessed this day” (CG124).

Discussion

Using in-depth interviews, focus groups, and surveys with clergy participants, this study describes spiritual issues encountered by clergy when ministering to patients with serious illness and key manifestations of clergy identity in providing what they view as optimal spiritual care. Consistent with patient surveys on religion and EOL,1 clergy identified the most common areas of patient struggles at EOL as existential questions, challenging emotions, and practical needs. Key manifestations of clergy identity in providing optimal spiritual care were described as “Being”, “Doing”, and “Believing” (Table 2). Congruence between the qualitatively derived categories, and survey data further support a conceptual framework (Fig. 1) based on these findings to inform development of a clergy educational program.

Fig. 1.

Proposed conceptual framework for community clergy end-of-life care education.

“Being” was discussed most clearly and frequently using language related to “presence.” Most clergy articulated a sense of privilege in the opportunity to be present and recognized its intangible importance; all agreed presence was a critical dimension of caring for patients facing serious illness. Although Being was considered fundamental to delivering optimal spiritual care at the EOL, most clergy appeared to seek a balance between passive aspects of spiritual care (exemplified by listening and well-timed words) and acts that were religiously directive (as described in “Doing” and “Believing”). “Doing” largely involved facilitating religious activities, grounded within the clergy’s respective faith tradition, and recognized the importance of ministering not only to patients but also to family caregivers who concurrently suffer during a terminal illness. In addition, clergy were candid regarding mistakes they had made in their own ministry or witnessed with other clergy. Active reflection on the challenges and lessons learned from providing spiritual care at the EOL may be particularly helpful as a springboard for discussion in educational programming for clergy. “Believing,” the third aspect of clergy identity in providing EOL care, focused on fostering a relationship with God, reassuring patients of an afterlife and salvation, and nurturing particular virtues, such as forgiveness and love, for patients to embrace. Community clergy understood these core beliefs as doctrines that shape their communication with patients, and although a few clergy expressed that imposing religious beliefs on patients was unethical, most expressed that certain beliefs were essential to emphasize at the EOL. In this approach, clergy indicated that they provided reassurance to patients experiencing spiritual doubt and, at times, challenged patients by encouraging a new or deeper relationship with God before death.

In developing a conceptual model that may be used for clergy education in EOL care, our data suggest that “Being”, “Doing”, and “Believing” are three dimensions of spiritual care that should operate in tandem when addressing patients’ spiritual concerns at the EOL. Historically, different religious traditions have tended to emphasize certain aspects of spiritual care such as presence among liberal Protestants, religious practices/rituals among Roman Catholics, and believing among Evangelicals, Pentecostals, and black clergy. Together, these three segments of American Christianity (Protestant, Roman Catholic, and Evangelical) comprise more than 90% of all U.S. clergy15 and approximately 70% of the U.S. population.16 Thus, EOL clergy education may likely need to give balanced attention to “Being”, “Doing”, and “Believing” to adequately engage multiple clergy viewpoints. This trifold understanding of optimal spiritual care may have important differences with interfaith and Clinical Pastoral Education hospital chaplaincy perspectives, which tend to de-emphasize “Believing” and stress a broad concept of spirituality (“Being”) vs. particular religious beliefs and practices.17,18 We propose that Clinical Pastoral Education, while an important model, may not be the best fit, or enough by itself, to train community clergy in EOL care. Our findings suggest that educational efforts for community clergy must incorporate all three dimensions of clergy identity (“Being”, “Doing”, and “Believing”) to effectively address patients’ religious needs at the EOL.

Similar to other reports,7 just over half of our clergy sample reported receipt of EOL training and two-thirds desired future training. Desire for EOL education among clergy provides palliative care leaders and educators an important opportunity to respond to national recommendations5,6 by equipping community clergy with the knowledge and training to improve care for patients at the EOL. Prior research suggests that as many as half of all U.S. patients apply religious beliefs to their experience of serious illness19 and receive input on medical decisions from their religious communities; this in turn impacts critical EOL choices, such as electing hospice or pursuing aggressive life-prolonging therapies.10 Although it is unsurprising that clergy offered prayer and read scripture when visiting the last congregational member who died, it is noteworthy that nearly half also helped the patient “sort through medical decisions” (Table 1). This dual role of providing spiritual support while helping patients and families navigate complex EOL medical decisions was described by one clergy participant as “helping [terminally-ill patients] to seek the balance of seeking treatment and accepting death” (TC1030). Future training may need to especially consider clergy influence on patient medical decisions.

The primary themes identified in our qualitative analysis suggest a theoretical underpinning to guide EOL programming for clergy and evaluate its impact. For example, in regard to helping patients navigate medical decision-making at the EOL, “Being” requires that clergy listen carefully to patients, families, and healthcare providers to understand more deeply the difficult medical choices under consideration; “Doing” may include praying for wisdom as patients face medical choices and direct facilitation of spiritual practices that remove anxiety, fear, and anger and help the patient look beyond their death to faith and hope in God; “Believing” may involve clergy and patients identifying the doctrines within their faith tradition that most appropriately apply to the medical context and specific choices that must be made. The theme of patient struggles experienced at the EOL (existential questions, practical concerns, and difficult emotions) suggests that these patient struggles are top priorities and could serve, at least to some degree, as possible outcome measures by which to evaluate the impact of educational programming designed to help clergy provide optimal spiritual care at the EOL.

A future clergy EOL curriculum will need to be especially attentive to the doctrinal beliefs that most appropriately apply to medical choices commonly encountered at the EOL, as some evidence suggests that religious communities may believe their “right” religious beliefs but apply them in the “wrong” manner.19–21 The palliative care community is especially equipped by virtue of their knowledge and expertise to respond to the growing recognition5,6 of the importance of partnering with clergy and clergy educators to develop EOL curricula that are both medically sound and theologically respectful.

Limitations

This study is designed to be hypothesis generating and, consistent with U.S. clergy demographics, reflects perspectives from a sample of predominantly Christian-affiliated, male, and theologically conservative clergy.15 The proposed conceptual framework represents the crucial (and understudied) perspective of community clergy and suggests an important first step in reconsidering how EOL training programs may be designed to best meet the educational needs of community clergy in a theologically holistic and respectful manner. However, our initial model does not incorporate the viewpoints of patients and family members or other healthcare practitioners who provide spiritual support at the EOL; future work should look to broaden this initial framework by incorporating these additional perspectives and further explore how optimal spiritual care is defined within the context of minority faith traditions. Also, although our study provides insights into possible programming content within the three domains of “Being”, “Believing”, and “Doing”, more work is needed to fully determine the specific content that best fits within the conceptual model.

Conclusion

Clergy perspectives of optimal spiritual care provide important insights to support a conceptual framework that can be used to guide educational EOL programming for clergy. This study identified three core dimensions that underlie community-based clergy’s understanding of their role as spiritual caregivers: “Being”, “Doing”, and “Believing”. This trifold model can be applied to help clergy address crucial patient concerns at the EOL, including navigating complex medical decisions. Future research should focus on refining the conceptual framework by considering additional perspectives (such as patients and family caregivers) and look toward the design, implementation, and evaluation of an EOL curriculum for community clergy informed by this conceptual framework.

Acknowledgments

The study was made possible by National Cancer Institute grant CA156732 and philanthropic support for the Initiative on Health, Religion, and Spirituality within Harvard University, including the John Templeton Foundation, the Issachar Fund, and individual donors.

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest or disclosures to report.

Contributor Information

Virginia T. LeBaron, University of Virginia School of Nursing, Charlottesville, Virginia.

Patrick T. Smith, Harvard Medical School Center for Bioethics and Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, Boston, Massachusetts.

Rebecca Quiñones, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, Massachusetts.

Callie Nibecker, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, Massachusetts.

Justin J. Sanders, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, Massachusetts.

Richard Timms, Scripps Clinic, La Jolla, California.

Alexandra E. Shields, Harvard/MGH Center on Genomics, Vulnerable Populations and Health Disparities, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts.

Tracy A. Balboni, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, Massachusetts, USAInitiative on Health, Religion, and Spirituality, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA.

Michael J. Balboni, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, Massachusetts, USAInitiative on Health, Religion, and Spirituality, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA.

References

- 1.Alcorn SR, Balboni MJ, Prigerson HG, et al. “If God wanted me yesterday, I wouldn’t be here today”: religious and spiritual themes in patients’ experiences of advanced cancer. J Palliat Med. 2010;13:581–588. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.0343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balboni TA, Vanderwerker LC, Block SD, et al. Religiousness and spiritual support among advanced cancer patients and associations with end-of-life treatment preferences and quality of life. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:555–560. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.9046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mamiya LH. Pulpit & Pew: Research on Pastoral Leadership. Durham, NC: Duke Divinity School; 2006. River of struggle, river of freedom: Trends among black churches and black pastoral leadership. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krause N, Bastida E. Social relationships in the church during late life: assessing differences between African Americans, whites, and Mexican Americans. Rev Relig Res. 2011;53:41–63. doi: 10.1007/s13644-011-0008-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Consensus Project. Clinical practice guidelines for quality palliative care. (2nd) 2009 Available at: www.nationalconsensusproject.org. Accessed October 5, 2015.

- 6.Puchalski C, Ferrell B, Virani R, et al. Improving the quality of spiritual care as a dimension of palliative care: the report of the Consensus Conference. J Palliat Med. 2009;12:885–904. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.0142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williams ML, Cobb M, Shiels C, Taylor F. How well trained are clergy in care of the dying patient and bereavement support? J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006;32:44–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Norris K, Strohmaier G, Asp C, Byock I. Spiritual care at the end of life. Some clergy lack training in end-of-life care. Health Prog. 2004;85:34–39. 58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abrams D, Albury S, Crandall L, Doka KJ, Harris R. The Florida Clergy End-of-Life Education Enhancement Project: a description and evaluation. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2005;22:181–187. doi: 10.1177/104990910502200306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Balboni TA, Balboni M, Enzinger AC, et al. Provision of spiritual support to patients with advanced cancer by religious communities and associations with medical care at the end of life. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:1109–1117. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hadaway CK, Marler PL. How many Americans attend worship each week? An alternative approach to measurement. J Sci Study Relig. 2005;44:307–322. [Google Scholar]

- 12.White K. An introduction to the sociology of health & illness. London, UK: Sage Publications, Ltd; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 13.LeBaron VT, Cooke A, Resmini J, et al. Clergy views of a good versus poor death: Ministry to the terminally Ill. J Palliat Med. 2015;18:1000–1007. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2015.0176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Corbin JM, Strauss AL. Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. 3rd. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carroll JW, McMillan BR. God’s potters: Pastoral leadership and the shaping of congregations. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Pub; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pew Reseach Center. America’s changing religious landscape 2015. Available at: www.pewforum.org/2015/05/12/americas-changing-religious-landscape/ Accessed October 5, 2015.

- 17.Handzo GF, Flannelly KJ, Kudler T, et al. What do chaplains really do? Interventions in the New York Chaplaincy Study. J Health Care Chaplain. 2008;14:39–56. doi: 10.1080/08854720802053853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cadge W. Paging God: Religion in the halls of medicine. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Phelps AC, Maciejewski PK, Nilsson M, et al. Religious coping and use of intensive life-prolonging care near death in patients with advanced cancer. JAMA. 2009;301:1140–1147. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sulmasy DP. Spiritual issues in the care of dying patients: “… it’s okay between me and God”. JAMA. 2006;296:1385–1392. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.11.1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Widera EW, Rosenfeld KE, Fromme EK, et al. Approaching patients and family members who hope for a miracle. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;42:119–125. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]