Abstract

HIV-infected youth experience many stressors, including stress related to their illness, which can negatively impact their mental and physical health. Therefore, there is a significant need to identify potentially effective interventions to improve stress management, coping, and self-regulation. The object of the study was to assess the effect of a mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) program compared to an active control group on psychological symptoms and HIV disease management in youth utilizing a randomized controlled trial. Seventy-two HIV-infected adolescents, ages 14–22 (mean age 18.71 years), were enrolled from two urban clinics and randomized to MBSR or an active control. Data were collected on mindfulness, stress, self-regulation, psychological symptoms, medication adherence, and cognitive flexibility at baseline, post-program, and 3-month follow-up. CD4+ T lymphocyte and HIV viral load (HIV VL) counts were also pulled from medical records. HIV-infected youth in the MBSR group reported higher levels of mindfulness (P = .03), problem-solving coping (P = .03), and life satisfaction (P = .047), and lower aggression (P = .002) than those in the control group at the 3-month follow-up. At post-program, MBSR participants had higher cognitive accuracy when faced with negative emotion stimuli (P = .02). Also, those in the MBSR study arm were more likely to have or maintain reductions in HIV VL at 3-month follow-up than those in the control group (P = .04). In our sample, MBSR instruction proved beneficial for important psychological and HIV-disease outcomes, even when compared with an active control condition. Lower HIV VL levels suggest improved HIV disease control, possibly due to higher levels of HIV medication adherence, which is of great significance in both HIV treatment and prevention. Additional research is needed to explore further the role of MBSR for improving the psychological and physical health of HIV-positive youth.

Keywords: Randomized controlled trial, mindfulness, medication adherence, adolescents, mental health

HIV-infected youth face a host of stressors, some of which are related to HIV. Psychological stress can accelerate HIV infection through both physiologic/immune and behavioral pathways, including decreased treatment adherence (Cohen, Janicki-Deverts, & Miller, 2007). Additionally, adolescence is a significant period for the development of self-regulation (Gestsdottir & Lerner, 2008). Challenges of the development of self-regulation combined with stress related to HIV diagnosis and treatment, make it salient and necessary to study effective approaches to improve the management of stress in HIV-infected youth.

The mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) program has been used in many clinical settings and populations with a range of chronic conditions (Grossman, Niemann, Schmidt, & Walach, 2004; Koerbel & Zucker, 2007; Niazi & Niazi, 2011). Developed by Kabat-Zinn (1990), MBSR is a structured 8-week program with the goal to enhance individuals’ awareness of the present moment (Brown, Ryan, & Creswell, 2007). Researchers have suggested the use of mindfulness programs with HIV-infected populations given its effectiveness in helping individuals develop stress management techniques, reduce physical and psychological symptoms, and develop a sense of overall well-being (Logsdon-Conradsen, 2002). MBSR has been shown to improve physical and psychological outcomes in HIV-infected adults (Alinaghi et al., 2012; Duncan et al., 2012; Gayner et al., 2012), and research on other mindfulness programs has shown psychological improvements in adolescents with HIV-infected parents (Sinha & Kumar, 2010). Moreover, research on mindfulness has begun to show significant changes in biological and physiological measures, such as brain structures and functioning, and HIV disease activity (Gonzalez-Garcia et al., 2014; Robinson, Mathews, & Witek-Janusek, 2003; Shao, Keuper, Geng, & Lee, 2016). Our previous research of MBSR in HIV-infected youth has been promising (Kerrigan et al., 2011; Sibinga et al., 2008, 2011), but we are not aware of any randomized controlled trials in this adolescent population.

The goal of this pilot trial was to test the effect of an adapted MBSR program on self-regulation and HIV disease in youth compared to a control program. We hypothesized that those in the MBSR program would have greater levels of mindfulness and other elements of self-regulation, as well as improved HIV disease management.

Methods

This was a pilot randomized controlled trial (RCT) of MBSR versus a health education control program for HIV-infected youth, with assessment of psychological symptoms and coping, cognitive flexibility, and HIV disease activity.

Participants

Participants were HIV-infected youth, 14–22 years old, receiving treatment at two urban clinics. Together, the clinics served approximately 370 HIV-infected youth, about 80% of whom are African American. During three separate recruitment periods at each site, 72 patients consented or assented (with parental consent) to participate in the study. Participants were reimbursed up to $160 for their participation in study activities and were provided with transportation for data collection and program sessions, as needed.

Procedures

Patients were eligible if they (1) received their medical care at one of the clinics, (2) did not have any significant cognitive, behavioral, or psychiatric disorders that could interfere with group-based activities, as determined by their clinical providers, and (3) had a current CD4 count above 200 (due to concerns about illness impacting group session attendance). Eligible patients were identified by the study coordinator and a clinic staff member at each site. If the patient was a minor, written consent was obtained from a parent or guardian, and patients provided written assent. Based on a computergenerated randomization scheme using a block size of four at each of the study sites, participants were randomized into either an MBSR intervention program or a general health education course (Healthy Topics [HT]).

Mindfulness-Based stress reduction program intervention

A nine-session MBSR program was adapted for youth using an iterative process during a previous pilot study (Sibinga et al., 2008). The adapted program was congruent with the typical structure and content of MBSR programs for adults (Kabat-Zinn, 1982). Consistent with MBSR for adults, the program has three central components: (1) didactic material on topics related to mindfulness (e.g., the connection between the mind and the body); (2) experiential practice of various mindfulness techniques during group sessions (e.g., meditations, yoga); and (3) discussions on the application of mindfulness to everyday life (Grossman et al., 2004; Kabat-Zinn, 1982; Sibinga et al., 2011). Formal and informal practices were included in the MBSR program, aimed to enhance present-focused awareness, reducing preoccupation with the past (i.e., Rumination) and the future (i.e., worry, anxiety; Jain et al., 2007).

General health education control program

“Healthy Topics” (HT) was an age-appropriate general health education program structured to match the MBSR sessions, including number and length of classes, location, didactic and experiential structure, and group size. The HT program covered topics of general health, such as nutrition, exercise, and puberty. The curriculum was adapted from the Glencoe Health Curriculum (McGraw Hill, 2005) and designed to control for the non-specific effects of a positive adult instructor, peer group experience, attention, and time.

Program instructor training

Instructors were selected based on their prior training and experience. MBSR instructors had attended in-person group training programs through the University of Massachusetts Center for Mindfulness, which includes at least 8 weekly sessions and a retreat. MBSR instructors also had extensive experience teaching mindfulness, and maintained long-standing personal practices. HT instructors participated in a three-hour training on the curriculum, and had experience in health education or a related field. Instructors for both programs had prior experience working with urban youth populations. Fidelity checklists were completed by all instructors after each session to ensure that the appropriate topics and activities were completed each week.

Data collection and measures

Participants completed self-report survey measures at baseline, immediately post-program, and at a 3-month follow-up visit. Validated surveys measured variables of psychological functioning, mindfulness, and medication adherence. Additionally, participants were administered individual color-word and emotion Stroop tasks at each data collection time point. CD4 and HIV viral load (HIV VL) counts during the study period were collected from the participants’ medical records.

The primary outcome was mindfulness, measured by the 15-item Mindful Attention and Awareness Scale (MAAS; MacKillop & Anderson, 2007), focusing on attention and acceptance in the moment. Its single-factor structure has been validated in samples of young adults and was found to be reliable within our sample (α = .79–.89; Brown et al., 2007).

The Perceived Stress Scale (PSS; Cohen, Kamarck, & Mermelstein, 1983) measured stress in participants, which had strong internal consistency in other HIV samples (Koopman et al., 2000). The 25-item Children’s Response Style Questionnaire assessed rumination, distraction, and problem-solving as coping strategies (Abela, Aydin, & Auerbach, 2007). The 11-item Aggression Scale was used to measure physical aggression (Orpinas & Frankowski, 2001). The 23-item HIV Quality of Life scale evaluated current life satisfaction, illness-related anxiety, and illness burden in the participants (Andrinopoulos et al., 2011). With the exception of the PSS (α = .54–.76), the measures were found to have good to excellent reliability in our sample (α = .76–.92).

Two validated Stroop task versions were administered through the course of the study as cognitive measures of self-regulation: the Cognitive Assessment System (CAS) Stroop task and the Color-Word Stroop (CWS; Golden & Freshwater, 1998; Naglieri & Das, 1997). Two versions of the stroop were given due to the age of our participants; individuals ages 14–17 completed the CAS, and individuals ages 18–22 completed the CWS. For the CAS Stroop, scaled scores were derived based on their time and accuracy. For the CWS, T-scores were calculated based on number of test items completed within a specified amount of time. To compare scores, a Stroop T-score was calculated for all study participants at each time point.

Additionally, the Emotion Stroop (ES) was conducted with each participant to measure expressive attention when presented with emotional stimuli. Due to our interest in the influence of MBSR on emotion regulation, an ES was developed for this study based on existing literature (Dalgleish, 2005; Yiend, 2010). Existing emotional Stroop tasks have focused on latency to respond to stimuli, as emotional context may place additional interference above the color-word interference in a traditional stroop task. The versions created for the study allowed an investigation of participant responses to positive and negative emotionally-valenced terms. The ES consisted of three 40-stimuli pages with emotionally-laden words printed in different colors by emotional valence: neutral words (e.g., anchor, clock), positive words (e.g., happy, beauty), or negative words (e.g., crash, enemy). To score the measure, each participant received a time score (time to complete) and an accuracy score (number of answers correct) for each stimulus page.

HIV medication adherence was measured with a 6-item self-report measure adapted by the investigators. The first two questions ask about HIV medications currently prescribed, followed by four questions asking about missed doses of HIV medication and adherence to medication schedules for the past four days and four weeks. These four items were combined to create an overall medication adherence measure in which higher scores indicated greater adherence. Data from medical records (CD4 counts and HIV VL) were used to assess HIV disease activity. Higher CD4 counts and lower HIV VL indicate better HIV disease management.

Statistical analyses

Analyses were conducted in STATA version 14 statistical software. Descriptive statistics were computed to characterize participants and track study attrition. Gender and age differences were assessed across intervention assignment and clinic site using χ2 and independent samples t-tests. Exploratory analyses were conducted to examine the relationships among mindfulness; stress; self-regulation processes of coping and psychological functioning; and HIV disease management by intervention assignment. Due to potential issues of multicollinearity between subscales of measures, multiple linear regression models were conducted for each post-program and follow-up outcome exploring the effects of the intervention, controlling for gender, age, site, and baseline variable. Post-program variables were also used in the follow-up regression models. HIV VL values were translated into a log scale and a 2.0 (i.e., 100 copies/mL) cutoff was selected based on laboratory thresholds at the time and baseline distribution to create two groups: < log 2.0 HIV VL (representing very low HIV disease activity), and ≥ log 2.0 HIV VL cutoff (representing greater HIV disease activity). Given the skewed distribution of data, dichotomized log-transformed baseline and 3-month follow-up HIV VL were compared using the non-parametric McNemar’s test.

Results

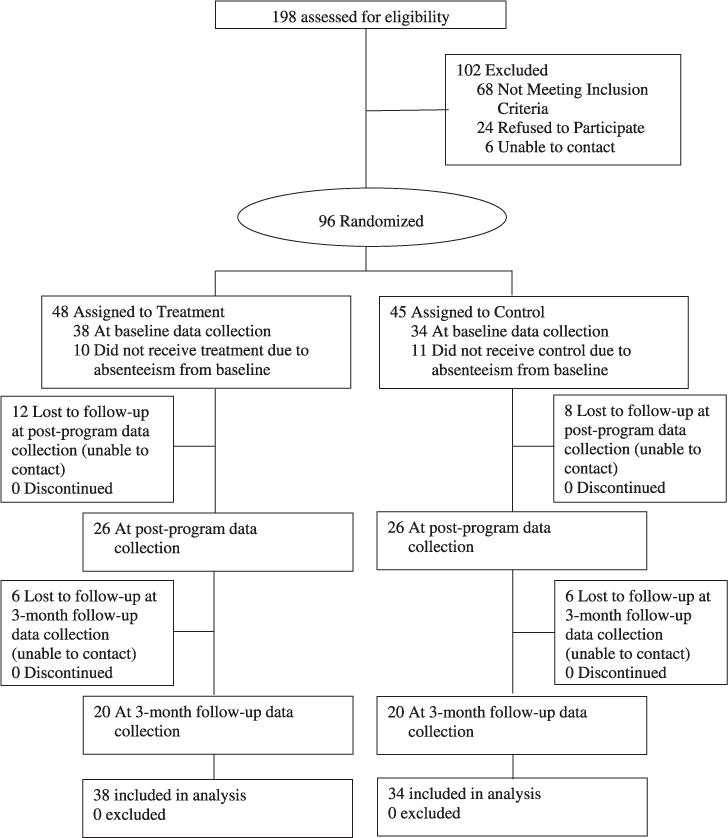

Seventy-two HIV-infected adolescents and young adults 14–22 years old (mean [SD]= 18.71, 2.31) participated in this pilot RCT (MBSR = 38, HT = 34). Randomization appeared to be effective, as no baseline differences were seen between the control and intervention groups (see Table 1). There was a gender difference between the two clinic sites (67.9% female vs 32.6% female, P = .003), therefore, in addition to gender, clinic site was included in regression models. Group attendance was similar, as MBSR and HT participants attended an average of 5.13 (range 0–9) and 5.82 (range 0–9) sessions, respectively. Reflecting the challenging nature of research in this study population, there was attrition during the study (Figure 1), with participants available for data collection as follows: baseline n = 72, post-program n = 52 (72%), three-month follow-up n = 40 (55%). Prior studies of mindfulness with HIV-infected populations had similar rates of attrition, ranging from 52% to 75% (Alinaghi et al., 2012; Fang et al., 2010; Robinson et al., 2003).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of MBSR and HT groups.

| Variables at Baseline | HT n = 34 (47.2%) |

MBSR n = 38 (52.8%) |

χ2 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 1.10 | .30 | ||

| Female | 18 (52.9) | 15 (39.5) | ||

| Male | 16 (47.1) | 22 (57.9) | ||

| Age | 0.07 | .80 | ||

| <18 years old | 8 (23.5) | 8 (21.1) | ||

| ≥18 years old | 18 (52.9) | 21 (55.3) | ||

| Site | 0.14 | .71 | ||

| Johns Hopkins | 14 (41.2) | 14 (36.8) | ||

| CHOP | 20 (58.8) | 24 (63.2) | ||

| HIV viral load | 3.45 | .06 | ||

| < log 2.0 | 17 (50.0) | 11 (28.9) | ||

| ≥ log 2.0 | 16 (47.1) | 26 (68.4) | ||

| Variable (range) | M (SD) | M (SD) | t | p-value |

| Mindfulness (1–6) | 3.95 (.83) | 3.89 (.63) | 0.32 | .75 |

| Perceived stress (0–4) | 2.07 (.56) | 2.25 (.62) | −1.26 | .21 |

| Coping | ||||

| Rumination (0–3) | 1.33 (.68) | 1.62 (.59) | −1.88 | .06 |

| Distraction (0–3) | 1.47 (.82) | 1.21 (.54) | 1.60 | .12 |

| Problem-Solving (0–3) | 1.47 (.71) | 1.47 (.75) | −0.01 | .99 |

| Aggression (0–6) | 1.15 (1.28) | 1.26 (1.14) | −0.35 | .73 |

| HIV quality of life | ||||

| Life satisfaction (1–5) | 2.05 (.75) | 2.31 (.87) | −1.34 | .19 |

| Illness Burden (1–5) | 1.63 (.78) | 1.86 (.72) | −1.27 | .21 |

| Illness Anxiety (1–5) | 2.18 (.68) | 2.36 (.73) | −1.04 | .30 |

| Medication Adherence (0–16) | 12.07 (4.18) | 11.53 (4.07) | 0.53 | .60 |

| CD4 count (12–1096) | 517.4 (282.9) | 493.2 (263.8) | 0.37 | .71 |

Figure 1.

Progression of participants through the trial.

Compared to the control arm, MBSR participants showed statistically significant benefits in several domains at the 3-month follow-up: MBSR participants endorsed higher levels of mindfulness (0.65; 95% CI [0.06–1.24]; P = 0.03), showed higher levels of problem-solving approaches to coping (0.49; 95% CI [0.05–0.92]; P = 0.03) and life satisfaction (0.57; 95% CI [0.01–1.13]; P = 0.05), and endorsed lower levels of aggression (−0.89; 95% CI [−1.41−0.37]; P = 0.002; see Table 2). There were no significant differences in perceived stress, the coping strategies of rumination or distraction, illness-related anxiety, or illness burden at either time point. Regarding cognitive flexibility, there were no differences between MBSR and HT groups at baseline; however, at post program, MBSR participants responded more accurately to the segment of the emotion Stroop task with negatively-valenced words than HT participants (0.33, 95% CI [0.05–0.61], P = .02). This finding was not seen at 3-month follow-up.

Table 2.

Outcomes means and regression results from models predicting to variable outcomes.

| Variables | HT n = 34 (47.2%) Mean (SD) |

MBSR n = 38 (52.8%) Mean (SD) |

Study Arm β (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Study Variables Post Program | |||

| Mindfulness | 4.08 (.91) | 3.67 (.80) | −.23 (−.77, .32) |

| Perceived Stress | 1.85 (.49) | 2.17 (.57) | .22 (−.13, .57) |

| Coping | |||

| Rumination | 1.22 (.65) | 1.46 (.63) | .05 (−.31, .40) |

| Distraction | 1.59 (.76) | 1.35 (.65) | −.24 (−.62, .14) |

| Problem-Solving | 1.75 (.74) | 1.62 (.64) | −.19 (−.56, .19) |

| Aggression | 1.37 (1.27) | 1.51 (1.38) | .17 (−.45, .79) |

| HIV Quality of Life | |||

| Life Satisfaction | 2.03 (.83) | 2.22 (.91) | −.03 (−.53, .46) |

| Illness Burden | 1.51 (.76) | 2.06 (.82) | .34 (−.06, .75) |

| Illness Anxiety | 2.06 (.15) | 2.48 (.85) | .23 (−.16, .61) |

| Medication Adherence | 10.70 (4.33) | 10.48 (3.99) | −.88 (−3.50, 1.73) |

| CD4 | 551.93 (333.81) | 477.83 (272.45) | −21.21 (−119.03, 76.61) |

| Emotion Stroop | |||

| Neutral Time | 34.88 (1.30) | 32.38 (1.48) | −2.65 (−5.85, .54) |

| Neutral Accuracy | 39.65 (.11) | 39.88 (.08) | .30 (−.05, .65) |

| Positive Time | 32.96 (1.35) | 33.46 (1.50) | .66 (−2.31, 3.63) |

| Positive Accuracy | 39.88 (.06) | 39.77 (.14) | −.16 (−.54, .22) |

| Negative Time | 34.88 (1.39) | 33.46 (1.54) | −1.74 (−5.47, 1.99) |

| Negative Accuracy | 39.68 (.11) | 39.92 (.05) | .33 (.05, .61)* |

| Study Variables Follow-Up | |||

| Mindfulness | 3.66 (.20) | 3.79 (.16) | .65 (.06, 1.24)* |

| Perceived stress | 1.88 (.12) | 1.99 (.12) | −.06 (−.44, .33) |

| Coping | |||

| Rumination | 1.18 (.13) | 1.54 (.18) | .31 (−.26, .88) |

| Distraction | 1.37 (.16) | 1.46 (.14) | .25 (−.12, .61) |

| Problem-Solving | 1.56 (.17) | 1.71 (.20) | .49 (.05, .92)* |

| Aggression | 1.44 (.27) | .96 (.29) | −.89 (−1.41, −.37)** |

| HIV Quality of Life | |||

| Life Satisfaction | 1.63 (.13) | 2.22 (.17) | .57 (.01, 1.13)* |

| Illness Burden | 1.36 (.12) | 1.86 (.17) | .03 (−.39, .44) |

| Illness Anxiety | 2.09 (.18) | 2.38 (.18) | .14 (−.33, .61) |

| Medication Adherence | 11.82 (4.56) | 12.11 (4.01) | 1.32 (−1.61, 4.25) |

| CD4 | 551.9 (52.3) | 496.6 (55.1) | 72.12 (−21.47, 165.71) |

| Emotion Stroop | |||

| Neutral Time | 31.45 (6.57) | 32.45 (7.96) | 1.32 (−2.85, 5.50) |

| Neutral Accuracy | 39.75 (.10) | 39.9 (.07) | .10 (−.21, .41) |

| Positive Time | 30.25 (6.06) | 33.05 (9.32) | −.29 (−3.72, 3.14) |

| Positive Accuracy | 40 (0) | 40 (0) | – |

| Negative Time | 33.75 (9.78) | 33 (8.19) | −2.39 (−7.70, 2.91) |

| Negative Accuracy | 39.85 (.37) | 39.75 (.64) | .01 (−.18, .20) |

Note:

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01. Each row represents a multiple linear regression model adjusted for age, gender, and clinic site.

Regarding HIV-related outcomes, there were no significant differences in self-reported HIV medication adherence or CD4 counts between groups at post-program or follow-up (Table 2). HIV VL were not different between arms at baseline. To assess for differences in HIV VL over time, McNemar’s test using 2 × 2 contingency tables of baseline and 3-month follow-up VL compares participants whose HIV VL changes between the two study time points (See Table 3). In the HT participants, there were no significant differences between participants whose HIV VL changed between baseline and follow-up, i.e., Went from low to high HIV VL (27% of those with low VL at baseline) or went from high to low HIV VL (27% of those with high VL at baseline; P = 0.21). However, McNemar’s test showed that, among MBSR participants, there was a significant difference for participants whose HIV VL changed between baseline and 3-month follow-up. As shown in Table 3, 8 of 18 (44%) MBSR participants with a high HIV VL at baseline (≥ log 2.0, reflecting higher HIV disease activity) exhibited a low HIV viral load (< log 2.0, representing very low HIV disease activity) at three-month followup and only 1 of 7 (14%) went from low HIV viral load at baseline to high HIV viral load at follow-up, both reflecting changes suggestive of improved HIV disease control from baseline to follow-up.

Table 3.

McNemar’s test of HIV viral load changes baseline to follow-up.

| HT HIV viral load |

Follow-up < log 2.0 | Follow-up ≥ log 2.0 | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline < log 2.0 | 11 (73%) | 4 (27%) | .21 |

| Baseline ≥ log 2.0 | 3 (27%) | 8 (73%) | |

| MBSR | |||

| HIV viral load | Follow-up < log 2.0 | Follow-up ≥ log 2.0 | P Value |

|

| |||

| Baseline < log 2.0 | 6 (86%) | 1 (14%) | .04a |

| Baseline ≥ log 2.0 | 8 (44%) | 10 (56%) | |

Significant difference between the quadrants representing change between time points, i.e., there is a greater likelihood that those in MBSR arm who had a high baseline viral load (VL) then had a low VL at 3-month follow-up (44% of those with high baseline VL) and/or there is a lower likelihood that those in the MBSR arm who had a low baseline VL then had a high VL at follow-up (14%).

Discussion

Results from this study suggest that MBSR can potentially be beneficial for HIV-infected youth. Compared with the control program, MBSR lead to increased mindfulness, problem-solving coping styles, life satisfaction, and increased regulation of negative emotional stimuli, while reducing aggression in HIV-positive youth. Importantly, MBSR youth were more likely to have changes in HIV VL at follow-up that represented significant improvements in HIV disease control.

The findings of MBSR’s potential psychological benefit are similar to results of studies in HIV-infected and non-HIV-infected adults (Gayner et al., 2012; Goyal et al., 2014; Grossman et al., 2004). These RCT findings in adolescents and emerging adults are a significant contribution to the field, as these youths are managing additional age-specific stressors related to HIV disease, such as identity formation and intimacy, are amidst the complex developmental tasks of adolescence, and are often in the setting of poverty and underresourced communities. That MBSR is effective in improving coping, emotion regulation, and life satisfaction among urban HIV-infected youth is significant, as these attributes may contribute positively to their developing self-regulation. Additionally, our previous research has shown that MBSR’s positive psychological impact is accompanied by positive behavioral changes related to decreased conflict engagement and increased self-care (Kerrigan et al., 2011; Sibinga, Perry-Parrish, Thorpe, Mika, & Ellen, 2014). Our trial also shows that MBSR participants with high HIV disease activity at baseline were significantly more likely to have low HIV VL at follow-up and/or that MBSR participants with low HIV VL at baseline were less likely to move to the high HIV VL category at follow-up. Given the significant drop in HIV VL to < log 2.0, it seems most probable that this decline in HIV disease activity reflects increased HIV medication adherence, potentially related to MBSR’s effect on self-care behavior directly and/or reduced anti-retroviral therapy (ART) side effects. Research in HIV-infected adults has found that MBSR can help alleviate the side effects of ART (Duncan et al., 2012), which may reduce barriers to medication adherence. Another possibility could be that MBSR affects mechanisms that improve participants’ immune system. In a quasi-experimental comparison group, pretest-posttest study of adults without HIV, those who participated in an MBSR group had increased natural killer cell numbers and activity (Robinson et al., 2003). Regardless of etiology, MBSR’s positive effect on HIV disease control in this challenging clinical scenario (uncontrolled HIV in urban adolescents) is of note, as MBSR may play an important adjunctive role in HIV treatment and prevention.

Consideration should be given to the limitations of this study. First, the modest sample size limits the power of our analyses and affects our ability to generalize to the larger population of HIV-positive youth. Second, there was variable attendance to the nine groups sessions, but this was balanced across arms. Third, the amount of attrition in our sample over the study period may have biased our findings, although rates of attrition were balanced across study arms and there were no baseline differences between those for whom we have data and those for whom we do not have data at follow-up. Participants who did not have post-program data had no or low attendance in the program. A similar finding was seen for those who did not have 3-month followup data. Since the regression analyses were conducted with data from participants for whom we had post-program and/or 3-month follow-up data, and these were the participants who had attended program sessions, it is likely that the data analyzed represent greater changes in our outcomes than those who did not attend the program and were not analyzed due to missing data. However, rates of attrition and missing data did not differ significantly by randomization into MBSR or HT, so the comparison between arms remains valid. Finally, the self-report measurement of medication adherence is complex and does little to explain the changes in the HIV VL seen in the trial. The challenge of precisely assessing adherence has been noted in the literature as well (Williams, Amico, Bova, & Womack, 2013).

Despite these limitations, this trial represents a significant contribution to the literature. This pilot RCT of MBSR versus HT for HIV-infected youth provides preliminary evidence of positive effects on meaningful and important outcomes, including improved coping and emotion regulation, improved life satisfaction, reduced aggression, and reduced HIV disease activity. These outcomes have the potential to positively affect the development of self-regulation in this vulnerable population. Future research should investigate the effects of MBSR in a larger sample of HIV-positive youth to replicate these findings, as well as further examining MBSR’s mechanism of effect in this population.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This study was funded by the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (R21AT005209) who provided monitoring throughout the study design, recruitment, and data collection period. Support was also received through the Johns Hopkins Center for AIDS Research, the Child Mental Health Services and Service System Research training grant (National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), PI: Philip Leaf, 4T32MH019545-25), and the NIDA Epidemiology Training Program (National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), PI: Renee Johnson, 5T32DA007292-25).

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Lindsey Webb http://orcid.org/0000-0001-5522-3533

References

- Abela J, Aydin C, Auerbach R. Responses to depression in children: Reconceptualizing the relation among response styles. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2007;35:913–927. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9143-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alinaghi S, Jam S, Foroughi M, Imani A, Mohraz M, Djavid GE, Black DS. RCT of mindfulness-based stress reduction delivered to HIV+ patients in Iran: Effects on CD4+ T lymphocyte count and medical and psychological symptoms. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2012;74(6):620–627. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31825abfaa. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrinopoulos K, Clum G, Murphy D, Harper G, Perez L, Xu J, Ellen JM. Health related quality of life and psychosocial correlates among HIV-infected adolescent and young adult women in the US. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2011;23(4):367–381. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2011.23.4.367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown KW, Ryan RM, Creswell JD. Mindfulness: Theoretical foundations and evidence for its salutary effects. Psychological Inquiry. 2007;18(4):211–237. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Janicki-Deverts D, Miller GE. Psychological stress and disease. JAMA. 2007;298(14):1685–1687. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.14.1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1983;24:385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalgleish T. Putting some feeling into it – the conceptual and empirical relationships between the classic and emotional stroop tasks: A commentary on algom, chajut and Lev (2004) Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 2005;134:585–591. doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.134.4.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan LG, Moskowitz JT, Neilands TB, Dilworth SE, Hecht FM, Johnson MO. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for HIV treatment side effects: A randomized wait-list controlled trial. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2012;43(2):161–171. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang CY, Reibel DK, Longacre M, Rosenzweig S, Campbell DE, Douglas SD. Enhanced psychosocial well-being following participation in a mindfulness-based stress reduction program is associated with increased natural killer cell activity. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2010;16(5):531–538. doi: 10.1089/acm.2009.0018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gayner B, Esplen MJ, DeRoche P, Wong J, Bishop S, Kavanagh L, Butler K. A randomized controlled trial of mindfulness-based stress reduction to manage affective symptoms and improve quality of life in gay men living with HIV. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2012;35:272–285. doi: 10.1007/s10865-011-9350-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gestsdottir S, Lerner RM. Positive development in adolescence: The development and role of intentional self-regulation. Human Development. 2008;51:202–224. doi: 10.1159/000135757. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Golden CJ, Freshwater SM. Stroop Color and Word Test – Adult Version 1998 [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Garcia M, Ferrer MJ, Borras X, Munoz-Moreno JA, Miranda C, Puig J, Fumaz CR. Effectiveness of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy on the quality of life, emotional status, and CD4 cell count of patients aging with HIV infection. AIDS and Behavior. 2014;18(4):676–685. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0612-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyal M, Singh S, Sibinga EM, Gould NF, Rowland-Seymour A, Sharma R, Haythornthwaite JA. Meditation programs for psychological stress and well-being: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2014;174(3):357–368. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.13018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman P, Niemann L, Schmidt S, Walach H. Mindfulness-based stress reduction and health benefits: A meta-analysis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2004;57:35–43. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00573-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain S, Shapiro SL, Swanick S, Roesch SC, Mills PJ, Bell I, Schwartz GE. A randomized controlled trial of mindfulness meditation versus relaxation training: Effects on distress, positive states of mind, rumination, and distraction. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2007;33:11–21. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3301_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn J. An outpatient program in behavioral medicine for chronic pain patients based on the practice of mindfulness meditation: Theoretical considerations and preliminary results. General Hospital Psychiatry. 1982;4:33–47. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(82)90026-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn J. Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness. New York, NY: Dell Publishing; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Kerrigan D, Johnson K, Stewart M, Magyari T, Hutton N, Ellen JM, Sibinga EM. Perceptions, experiences, and shifts in perspective occurring among urban youth participants in a mindfulness-based stress reduction program. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice. 2011;17:96–101. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2010.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koerbel LS, Zucker DM. The suitability of mindfulness-based stress reduction for chronic hepatitis C. Journal of Holistic Nursing. 2007;25(4):265–274. doi: 10.1177/0898010107304742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koopman C, Gore-Felton C, Marouf F, Butler LD, Field N, Gill M, Spiegel D. Relationships of perceived stress to coping, attachment and social support among HIV-positive persons. AIDS Care. 2000;12(5):663–672. doi: 10.1080/095401200750003833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logsdon-Conradsen S. Using mindfulness meditation to promote holistic health in individuals with HIV/AIDS. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2002;9:67–72. [Google Scholar]

- MacKillop J, Anderson E. Further psychometric validation of the mindfulness attention awareness scale (MAAS) Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2007;29(4):289–293. [Google Scholar]

- McGraw-Hill. 2005 http://www.glencoe.com/sec/health/th12005/index.php/md.

- Naglieri JA, Das JP. Cognitive Assessment System 1997 [Google Scholar]

- Niazi AK, Niazi SK. Mindfulness-based stress reduction: A non-pharmacological approach for chronic illnesses. North American Journal of Medical Sciences. 2011;3:20–23. doi: 10.4297/najms.2011.320. 10.4297/najms.org. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orpinas P, Frankowski R. The aggression scale: A self-report measure of aggressive behavior for young adolescents. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 2001;21:50–67. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson FP, Mathews HL, Witek-Janusek L. Psycho-endocrine-immune response to mindfulness-based stress reduction in individuals infected with the human immunodeficiency virus: A quasiexperimental study. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2003;9:683–694. doi: 10.1089/107555303322524535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao R, Keuper K, Geng X, Lee TMC. Pons to posterior cingulate functional projections predict affective processing changes in the elderly following eight weeks of meditation training. EBioMedicine. 2016;10:236–248. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibinga EMS, Kerrigan D, Stewart M, Johnson K, Magyari T, Ellen JM. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for urban youth. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2011;17(3):213–218. doi: 10.1089/acm.2009.0605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibinga EM, Perry-Parrish C, Thorpe K, Mika M, Ellen JM. A small mixed-method RCT of mindfulness instruction for urban youth. EXPLORE: The Journal of Science and Healing. 2014;10(3):180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.explore.2014.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibinga EMS, Stewart M, Magyari T, Welsh CK, Hutton N, Ellen JM. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for HIV-infected youth: A pilot study. EXPLORE: The Journal of Science and Healing. 2008;4(1):36–37. doi: 10.1016/j.explore.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha UK, Kumar D. Mindfulness-based cognitive behavior therapy with emotionally disturbed adolescents affected by HIV/AIDS. Journal of Indian Association for Children and Adolescent Mental Health. 2010;6(1):19–30. [Google Scholar]

- Williams AB, Amico KR, Bova C, Womack JA. A proposal for quality standards for measuring medication adherence in research. AIDS and Behavior. 2013;17(1):284–297. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0172-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yiend J. The effects of emotion on attention: A review of attentional processing of emotional information. Cognition & Emotion. 2010;24(1):3–47. doi: 10.1080/02699930903205698. [DOI] [Google Scholar]