Summary

Background/objective

When researchers or developers wish to apply their findings to clinical usages, it must be approved by public authorities such as the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). In addition to the development records and risk control documents, all of the materials and testing must be completed by laboratories or manufacturers with good quality controls in accordance with related regulations or standards. The Orthopaedic Device Research Center dynamic hip screw system (ODRC-DHS system), which was developed by the ODRC, National Yang-Ming University, Taipei, Taiwan, obtained FDA 510(k) clearance in 2011.

Methods

The application process was divided into five steps: (1) make sure that the product is a medical device and classify it; (2) find the predicate devices cleared by the FDA; (3) research any standards and/or guidance documents; (4) prepare the appropriate information for premarket submission to the FDA; and (5) send premarket submission to the FDA and interact with the FDA staff.

Results and Conclusion

The relevant regulations, guidelines, and strategies were detailed by step-by-step demonstration so that readers can quickly understand the requirements and know-how of a translational research.

Keywords: FDA 510(k), medical device, SCI, translate

Introduction

Many organizations use Science Citation Index (SCI) papers to assess the performance of researchers. However, engineers in undeveloped or developing countries could seldom read SCI papers due to language barriers or reading habits. This phenomenon means that the research results of these countries are unable to provide any substantial benefit to citizens. Therefore, translational research which not only profits the research team but also benefits the people has become very important.

To translate a research result into a legal medical device, additional evidence or documents are needed to ensure the quality and consistency of a product, such as the demonstration of contraindications, the approaches in reducing the risk, and the controls of production processes including manufacturing, cleaning, and sterilization. The requirements for a SCI paper and a medical device are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

General Requirements for SCI papers and medical devices.

| SCI paper | Medical device | |

|---|---|---|

| Indicationsa | Yes | Yes |

| Contraindicationsb | No | Yes |

| Effectiveness | Yes | Yes |

| Safety | No | Yes |

| Quality system | No | Yes |

SCI = Science Citation Index.

Indications denote the disease or condition the device will diagnose, treat, prevent, cure, or mitigate, including a description of the target patient population.

Contraindications denote when the device should not be used.

A medical device is intended for use in saving or protecting the health of individuals, therefore it should not be used if the foreseeable risks clearly outweigh the benefits of use. For this reason, public authorities pay more attention to the risks and quality control of medical devices. They have set documents of regulations and/or guidance for medical devices, which must be fully complied with, to ensure the safety and effectiveness of devices [1], [2], [3], [4], [5]. The best strategy for preparing the submission of a medical device is to follow the available methods and the international standards and guidance documents. If existing regulations, standards or guidances cannot be found, it is possible that it is a new device and classed as Class III. Therefore, it may need to follow the premarket approval (PMA) submission process.

In different countries, the medical device classification and the required documents for license can be quite varied. The following introduction focused on the United States Food and Drug Administration (US FDA) criteria. Applicants can adopt the following steps prior to marketing a medical device in the US:

Step 1: Make sure that the product is a medical device and classify it.

Medical devices marketed in the US are subject to the regulatory controls in the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act (FD&C Act) [1] and the regulations in the Title 21- Code of Federal Regulations (21 CFR) Parts 1–58, 800–1299. According to the definition in Section 201(h) of the FD&C Act, a medical device is:

“an instrument, apparatus, implement, machine, contrivance, implant, in vitro reagent, or other similar or related article, including a component part, or accessory which is:

-

•

recognized in the official National Formulary, or the United States Pharmacopoeia, or any supplement to them,

-

•

intended for use in the diagnosis of disease or other conditions, or in the cure, mitigation, treatment, or prevention of disease, in man or other animals, or

-

•

intended to affect the structure or any function of the body of man or other animals, and which does not achieve its primary intended purposes through chemical action within or on the body of man or other animals and which is not dependent upon being metabolized for the achievement of any of its primary intended purposes.”

Many researchers believe that their products are medical devices, however, the products may not meet the above definitions. This will lead to unsuccessful licensing of the products. Medical devices are categorized into three classifications according to the risks of the devices by the US FDA as Class I, Class II and Class III (Table 2) according to Section 360c(a) of the FD&C Act [1]. The risks that a device poses to patients and the FDA regulatory control vary with the classifications. Medical devices in Class I typically possess simple designs and construction that present minimal potential harm to users with a history of safe use, so they should only comply with general controls. Medical devices in Class II are those whose sufficient safety and effectiveness cannot be assured by general controls, although the existing methods and the international standards and guidance documents are available to provide scientific evidences of safety and effectiveness. As well as complying with general controls, devices in this classification must conform to special controls. Premarket notification, i.e., submission and the FDA review of a 510(k) clearance, is required for the legal marketing of some Class I devices, nearly all Class II devices, and a very small number of Class III devices. Class III devices are usually used for supporting or sustaining human's life, or preventing a potential unreasonable risk of illness or injury in patients. The most stringent regulatory controls are set for Class III medical devices because the information provided by general controls and special controls is insufficient to assure safety and effectiveness. Typically, a PMA submission to the FDA is required in order to market a Class III medical device.

Table 2.

FDA medical device classifications.

| Classifications a | Risk | Level of regulatory control |

|---|---|---|

| Class I | Minimal | General controls |

| Class II | Medium | General controls and special controls (510k) |

| Class III | High | General controls and PMA |

FDA = Food and Drug Administration; PMA = premarket approval.

The classifications are according to Section 360c(a) of the FD&C Act [1].

It is very difficult for applicants to classify the products. Fortunately, the FDA has a classification database to help people finish this step [6]. Applicants can use this database by typing the name of a product with simple related terms to make sure that the classification of the product matches with the descriptions provided.

Step 2: Find the predicate devices cleared by the FDA.

The predicate devices mean the similar medical devices that have already been cleared by the FDA. An FDA 510(k) submission is based on the comparisons of products with the predicate devices. The FDA 510(k) database is the best way to find the predicate devices [7].

Step 3: Research any standards and/or guidance documents.

International Organization for Standardization (ISO) 14971 is one of the most useful standards [8]. It states: “This International Standard specifies a process for a manufacturer to identify the hazards associated with medical devices, including in vitro diagnostic (IVD) medical devices, to estimate and evaluate the associated risks, to control these risks, and to monitor the effectiveness of the controls.” It provides an overview of the risk management process for medical devices and a series of questions that can be used to identify the characteristics of medical devices which could impact on safety. Following the process, the risks of medical devices can be evaluated systematically. The most common risks of orthopaedic devices include biocompatibility (e.g., toxicity of chemical constituents) and mechanical energy hazards (e.g., torsion, shear or tensile force). These risks must be reduced to an acceptable level. The main factors which would cause the above-mentioned risks are raw materials and the quality control of a production process. Inappropriate raw materials may have a composition that has adverse effects on human. The contamination, inadequate cleaning, or sterilizing process during processing may increase biocompatibility concerns. Furthermore, undesirable mechanical properties of use or poor processing quality could affect the effectiveness of orthopaedic devices or even increase the risk of failure.

When preparing the 510(k) documents for submission, it is most important to provide sufficient evidence of effectiveness and safety of the product. It is necessary to prove that the product would not cause adverse reactions in patients, i.e., the biocompatibility of the product. ISO 10993 is a part of the international harmonization of the evaluation of safety of medical devices, which entails a series of standards for evaluating the biocompatibility. ISO 10993-1:2009 [9] describes the general categorization of devices based on the nature and duration of their contact with body and suggests the necessity of biocompatibility tests. It will take a lot of time and cost to complete those tests.

In order to reduce potential biocompatibility risks, The American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) and ISO have established the standards for materials commonly used for orthopaedic devices, such as metallurgical, ceramic and polymeric materials [10], [11], [12]. Both chemical compositions and mechanical properties of materials for a surgical implant are clearly defined in these standards. Using certified medical grade materials to produce orthopaedic devices is the easiest way to meet the regulatory requirements.

Additionally, it is necessary to strengthen the quality control of manufacturing processes. ISO 13485 [13] is an excellent reference standard which specifies not only the control of the premarket product design, the manufacturing process and the product quality, but also the control of the postmarket surveillance. An ISO 13485 certificate represents that the production quality of the manufacturer reaches a fairly high level. Unqualified products or unstable quality between lots are unlikely to happen. Therefore, the common risks of medical devices can be reduced greatly by contracting out to a facility which holds an ISO 13485 certificate.

Usually, the effectiveness and security of orthopaedic devices are evaluated through mechanical tests. Unfortunately, it is difficult to compare test results from different laboratories due to the differences in testing equipment and parameters. Therefore, the ASTM and ISO developed a series of mechanical testing standards for orthopaedic devices, for example, ASTM F382 [14] and ISO 9585 [15] are the testing standards for bone plates, and ISO 7206-4 [16] and ISO 7206-6 [17] are the testing standards for hip prosthesis at different parts. Based on the indications and characteristics of orthopaedic devices, appropriate standards should be followed so that the credibility of the test results will be increased and accepted easily by public authorities.

Step 4: Prepare the appropriate information for premarket submission to the FDA.

In order to confirm the effectiveness and safety of a product, a lot of inevitable testing must be completed. But how can the credibility of the test reports be confirmed? ISO/International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) 17025 [18] is the most important standard for calibration and testing laboratories around the world. Laboratories that are accredited to this international standard have demonstrated that they are technically competent and able to produce precise and accurate tests and/or calibration data. The FDA does not enforce the qualifications of testing laboratories. However, if a test report is completed by a laboratory with the ISO 17025 certification, it could provide a highly reliable report and reduce potential problems during the review processes.

Step 5: Send premarket submission to the FDA and interact with the FDA staff.

After all safety and performance tests are finalized, applicants must prepare application documents and submit the 510(k) to the FDA. If successful, they will receive a 510(k) clearance letter from the FDA with a 510(k) number. The FDA promises to review the submissions within 90 days, but the timeline can vary depending on the product and the integrity of the applied documents.

Materials and methods

Orthopaedic Device Research Center (ODRC, National Yang-Ming University, Taipei, Taiwan) developed a medical device which is an antisubsidence dynamic coupling fixation plate for proximal femur fracture, namely “ODRC dynamic hip screw system (ODRC-DHS)”. The system consists of nonsterile ODRC-DHS plates, ODRC-DHS screws, ODRC-DHS blades, compression screws and 4.5 mm cortex screws (Figure 1). Results of finite element analysis and biomechanical testing showed that this product achieved the intended purpose effectively. Thus, this product becomes a candidate for the FDA application.

Figure 1.

The schematic diagram of the ODRC dynamic hip screw system. ODRC-DHS = Orthopaedic Device Research Center-dynamic hip screw.

Step 1

ODRC-DHS system achieves its primary intended purpose through simple biomechanics. There is no chemical action and metabolism within or on the body of patients after implantation. Through querying the FDA classification database using plate and screw as keywords, the results showed that this product can be classified as Class II: Plate, Fixation, Bone (CFR 888.3030) or Class II: Screw, Fixation, Bone (CFR 888.3040). As the product fully meets the definition of the FDA Class II medical device, the FDA 510(k) application process should commence.

Step 2

The FDA 510(k) database was searched and the indications were compared. The SYNTHES DHS System (K981757) was chosen as the predicate device of this 510(k) application.

Step 3

In order to meet the biocompatibility considerations, ODRC outsourced a facility which holds an ISO 13485 certificate to manufacture the products from the medical grade 316L stainless steel that meets ASTM F138 [19], ASTM F139 [20] and ISO 5832-1 [21]. Therefore, the material certification from the material supplier could be used instead of the biocompatibility test reports.

According to the characteristics and indications of the ODRC dynamic hip system, the standards of ASTM F382 [14], ASTM F384 [22] and ASTM F543 [23] can be found within the ASTM website. Following the above standards, ODRC executed biomechanical properties tests of the ODRC dynamic hip screw system and the predicate device. The results indicated that the biomechanical properties of both products were similar.

Although the ODRC dynamic hip screw system is a nonsterile product, the sterilization parameters must be provided in the application documents. Therefore, ODRC commissioned the Europe America Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Taichung, Taiwan) to complete a moist heat validation test to find the appropriate sterilization parameters. The test was conducted based upon ISO 17665-1 [24] and ISO 17665-2 [25].

Steps 4 and 5

The application documents should enclose the forms requested by the FDA, the product descriptions, the engineering drawings, the dimensions and specifications, the material certification, the biomechanical test report, and the moist heat sterilization validation test report, etc. Finally, a comparison table with basic information and features of both products was created to show that the ODRC-DHS system and the predicate device were substantially equivalent (Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of specific features of new device and legally marketed predicate device.

| Comparable features | ODRC-DHS system | SYNTHES DHS system | SE? |

|---|---|---|---|

| 510(k) No. | (This submission) | K981757 | |

| Components | ODRC-DHS plates ODRC-DHS screws ODRC-DHS blades, compression screw, and 4.5 mm cortex screw. |

DHS plates Lag screw compression screw and |

Yes |

| Intended use | Fixation of fractures to the proximal femur | Fixation of fractures to the proximal femur | Yes |

| Indication for use | The system is indicated for use in trochanteric, pertrochanteric, intertrochanteric and basilar neck fractures. | The system is indicated for use in trochanteric, pertrochanteric, intertrochanteric and basilar neck fractures. | Yes |

| Material | Stainless steel | Stainless steel | Yes |

| Use | Single use | Single use | Yes |

| Method of sterilization | Nonsterile | Nonsterile | Yes |

| Mechanical testing | ASTM F382, F384 and F543 | ASTM F382, F384 and F543 | Yes |

ASTM = American Society for Testing and Materials; ODRC-DHS = Orthopaedic Device Research Center-dynamic hip screw; SE = substantially equivalent.

Results

The chronicle of the ODRC-DHS system application is listed as follows:

October 8, 2010, submitted to the FDA

October 14, 2010, received an acknowledgement letter

January 11, 2011, received a refuse to accept letter and an additional information request

April 1, 2011, resubmitted responses to the FDA

April 23, 2011, received a 510(k) decision letter, K103015

Apart from some omissions or unclear instructions that needed to be amended, the main additional information requested in this submission was:

“Provide a statement of whether device will be or is “pyrogen free” and a description of the method used to make that determination if you are claiming the device will be pyrogen free.”

Therefore, ODRC commissioned SGS Taiwan Ltd. (Taipei, Taiwan) to complete a rabbit pyrogen test to determine whether the device was pyrogen free or not. The test was conducted based upon the ISO 10993-12 [26] and ISO 10993-11 [27]. The result concluded that the pyrogen study was negative, therefore, the test article extract was considered as “pass” in the pyrogen study.

After reorganizing the application documents by correcting all omissions or unclear instructions and providing the new study report, ODRC resubmitted the application documents to the FDA. Fortunately, based on the documents provided by ODRC, the FDA agreed that ODRC-DHS system and the predicate device SYNTHES DHS System (K981757) were substantially equivalent on October 24, 2011. From 2014 to 2015, eleven female osteoporotic patients with intertrochanteric fractures of the femur and T-scores under –2.5 were enrolled to a prospective study. The average age was 82 years old and duration of follow-up was 90 days to 255 days. The clinical results showed that there were good fracture unions in the ten patients and no lag-screw cutout occurred. The postoperative X-ray images of one patient are shown in Figure 2. The preliminary follow-up results show that this ODRC-DHS system did reduce lag-screw cutout complications in patients with osteoporosis [28].

Figure 2.

X-ray images of the implanted ODRC-DHS system. ODRC-DHS = Orthopaedic Device Research Center-dynamic hip screw.

Discussion

Only the FDA 510 (k) process was indicated in this article. Dynamic hip screw, which has extensive use in orthopaedics, is a typical Class II product. If there is a lack of clinical experience in the use of the product, it may be classified as Class III, i.e., a higher risk product. In such cases, the product may need a clinical trial and the FDA PMA process.

In this application, the material certification was used instead of the biocompatibility test report. In general, ISO 10993 is a part of the international harmonization of the safety evaluation of medical devices, which entails a series of standards for evaluating the biocompatibility. ISO 10993-1:2009 [9] describes the general categorization of devices based on the nature and duration of their contact with body and suggests the necessity of biocompatibility tests. It will take a lot of time and cost to complete those tests. Unfortunately, the time and funds required for those tests are far more than general laboratories can afford.

Both raw material and manufacturing process are the major factors that may induce biocompatibility concerns. In order to eliminate these concerns, ODRC adopted commercially available medical grade materials and outsourced the products to a facility which holds an ISO 13485 certificate. Therefore, in the case of providing the material certification alone, the FDA reviewers only requested a pyrogen study in this application. It took only 2 weeks to complete this study and cost ODRC approximately $1000, which would be an affordable cost for laboratories in universities.

The test methods and executive organizations are the major factors in the impact of the reliability in a test report. There were three test reports provided in this application. Both the moist heat sterilization validation test report and pyrogen study report were accomplished by ISO 17025 accredited laboratories and followed the relevant standards. However, the biomechanical test report was completed by ODRC, which is not an ISO 17025 accredited laboratory. The FDA reviewers endorsed this report because the report was fully in accordance with the relevant standards. This experience showed that reports from a nonaccredited laboratory could also provide sufficient reliability as long as the test was stringently completed.

In addition, a very important thing for the readers to keep in mind is that the regulations, guidance documents and standards of medical devices may be modified occasionally. During the development of medical devices, the manufacturers or regulators should always pay attention to the updated relevant regulations.

For example, ODRC mailed two hard copies of submission documents to the FDA for 510(k) application in 2010. However, the FDA issued a final guidance document entitled “eCopy Program for Medical Device Submissions” on December 31, 2012 announcing that including an eCopy with your submission has been required since January 1, 2013. If a submission without or with an eCopy that does not meet the technical standards outlined in the eCopy guidance, it will be placed on eCopy holds until a valid eCopy is received. The latest eCopy guidance was issued on December 3, 2015 [29]. Also, on 25 February, 2016 the ISO released the ISO 13485:2016. It is the global standard for medical device quality management systems which will replace the previous version of 2003. The ISO 13485:2003 and ISO 13485:2016 will coexist for the next three years in order to allow manufacturers, accreditation/certification bodies and regulators to have enough time to transit to the new standards [30].

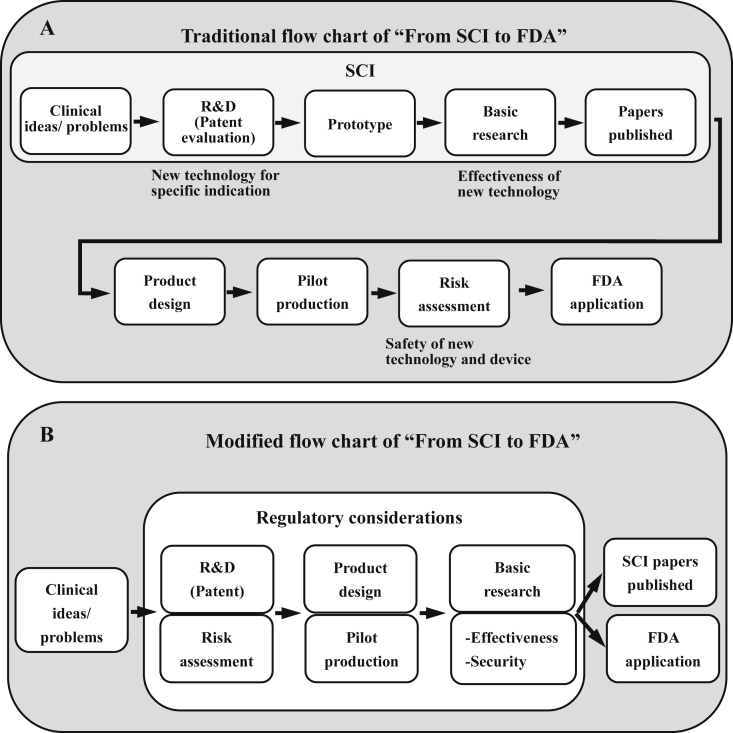

The traditional flow chart of “From SCI to FDA” is schematically represented in Figure 3A. The findings or proving of a concept could be accepted as an SCI paper. However, more solid and reliable evidence is needed for a medical device. As well as indications/contraindications and effectiveness which are indispensable to a medical device, public authorities pay more attention to the risks and quality control of devices (Figure 4). Our regular practice is a scientific development followed by a translational research, which is time-consuming and costly. However, publishing SCI papers is not usually contrary to the FDA application. The laboratory test results could be used as the FDA 510 (k) application documents as long as the testing specimen processes and reports meet the latest regulatory considerations. Therefore, the authors would like to recommend that researchers should include regulation considerations during the development period, which could reduce the time and cost of the translational research. The modified flow chart of “From SCI to FDA” is shown in Figure 3B.

Figure 3.

(A) Traditional and (B) modified flow chart of translating SCI to FDA. FDA = Food and Drug Administration; SCI = Science Citation Index.

Figure 4.

Essential requirements of FDA /CFDA for medical implants registration. ASTM = American Society for Testing and Materials; CFDA = China Food and Drug Administration; FDA = Food and Drug Administration; GMP = good manufacturing practices; ISO = International Organization for Standardization.

Translational research is not difficult providing it meets the regulatory requirements. However, less than 20% of medical device value is engineering related and more than 50% is created by market channel [31]. Therefore, a successful translational research must prove that new medical devices can provide better results than current treatments in order to facilitate the promotion and marketing of products. In addition, intellectual property will provide adequate protection against counterfeiting of products. It is very important for researchers to apply for a patent before SCI publication and license application.

Conclusion

A SCI paper, which describes whether a certain idea or concept is correct or not, is a scientific achievement. However, translational research should be encouraged in order to translate the research results into medical devices and promote public welfare. The development of medical devices seems complicated, but is simple in nature. Although a lot of scientific evidence must be prepared, the translational work can be completed smoothly by reading and following all the existing guidance documents, directives, and standards carefully.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding/support

No financial or grant support was received for the work described in this article.

References

- 1.The Federal Food, Drug & Cosmetic Act, U.S. Congress, Washington DC, U.S.

- 2.Guidance for Industry and FDA Staff: Format for Traditional and Abbreviated 510(k)s, Center for Devices and Radiological Health, Food and Drug Administration, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Maryland, U.S.

- 3.Medical Devices Directive 93/42/EEC, Council of the European Union, Brussels, Belgium.

- 4.Active Implantable Medical Devices 90/335/EEC, Council of the European Union, Brussels, Belgium.

- 5.In Vitro Diagnostic Directive 98/79/EC, Council of the European Union, Brussels, Belgium.

- 6.FDA Product Classification database. Available at https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfpcd/classification.cfm [accessed 29.07.2016].

- 7.FDA 510(k) Premarket Notification database. Available at https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfpmn/pmn.cfm [accessed 29.07.2016].

- 8.ISO 14971:2007. Medical devices—Application of risk management to medical devices. International Organization for Standardization, Geneva, Switzerland.

- 9.ISO 10993–1:2009. Biological evaluation of medical devices—Part 1: Evaluation and testing within a risk management process. International Organization for Standardization, Geneva, Switzerland.

- 10.ASTM Medical Device Standards and Implant Standards. Available at http://www.astm.org/Standards/medical-device-and-implant-standards.html [accessed 29.07.2016].

- 11.The ISO standards catalogue 11.040.40: Implants for surgery, prosthetics and orthotics. Available at http://www.iso.org/iso/iso_catalogue/catalogue_ics/catalogue_ics_browse.htm?ICS1=11&ICS2=040&ICS3=40 [accessed 29.07.2016].

- 12.ISO/TC 194-Biological evaluation of medical devices. Available at http://www.iso.org/iso/home/store/catalogue_tc/catalogue_tc_browse.htm?commid=54508 [accessed 29.07.2016].

- 13.ISO 13485:2003. Medical devices—Quality management systems—Requirements for regulatory purposes. International Organization for Standardization, Geneva, Switzerland.

- 14.ASTM F382-99(2008)e1. Standard Specification and Test Method for Metallic Bone Plates. American Society of the International Association for Testing and Materials, Pennsylvania, U.S.

- 15.ISO 9585:1990. Implants for surgery—Determination of bending strength and stiffness of bone plates. International Organization for Standardization, Geneva, Switzerland.

- 16.ISO 7206–4:2010. Implants for surgery—Partial and total hip joint prostheses—Part 4: Determination of endurance properties and performance of stemmed femoral components. International Organization for Standardization, Geneva, Switzerland.

- 17.ISO 7206–6:2013. Implants for surgery—Partial and total hip joint prostheses—Part 6: Endurance properties testing and performance requirements of neck region of stemmed femoral components, International Organization for Standardization, Geneva, Switzerland.

- 18.ISO/IEC 17025:2005. General requirements for the competence of testing and calibration laboratories. International Organization for Standardization, Geneva, Switzerland.

- 19.ASTM F138-13a. Standard Specification for Wrought 18Chromium-14Nickel-2.5Molybdenum Stainless Steel Bar and Wire for Surgical Implants, American Society of the International Association for Testing and Materials, Pennsylvania, U.S.

- 20.ASTM F139-12. Standard Specification for Wrought 18Chromium - 14Nickel - 2.5Molybdenum Stainless Steel Sheet and Strip for Surgical Implants. American Society of the International Association for Testing and Materials, Pennsylvania, U.S.

- 21.ISO5832–1:2007. Implants for surgery—Metallic materials—Part 1: Wrought stainless steel. International Organization for Standardization, Geneva, Switzerland.

- 22.ASTM F384-06e1. Standard Specifications and Test Methods for Metallic Angled Orthopedic Fracture Fixation Devices. American Society of the International Association for Testing and Materials, Pennsylvania, U.S.

- 23.ASTM F543-07e2. Standard Specification and Test Methods for Metallic Medical Bone Screws. American Society of the International Association for Testing and Materials, Pennsylvania, U.S.

- 24.ISO 17665–1:2006. Sterilization of health care products—Moist heat—Part 1: Requirements for the development, validation and routine control of a sterilization process for medical devices. International Organization for Standardization, Geneva, Switzerland.

- 25.ISO 17665–2:2009. Sterilization of health care products—Moist heat—Part 2: Guidance on the application of ISO 17665–1. International Organization for Standardization, Geneva, Switzerland.

- 26.ISO 10993–12:2007. Biological evaluation of medical devices—Part 12: Sample preparation and reference materials. International Organization for Standardization, Geneva, Switzerland.

- 27.ISO 10993–11:2006. Biological evaluation of medical devices—Part 11: Tests for systemic toxicity. International Organization for Standardization, Geneva, Switzerland.

- 28.Chen T.H. 2015. A Novel Dynamic Hip Screw Design for Femoral Intertrochanteric Fracture: The Excellent Outcome in Osteoporosis Patients. The 10th International Congress of Chinese Orthopaedic Association. Beijing, China. [Google Scholar]

- 29.eCopy Program for Medical Device Submissions. Available at http://www.fda.gov/downloads/MedicalDevices/DeviceRegulationandGuidance/GuidanceDocuments/UCM313794.pdf [accessed 29.07.2016].

- 30.New ISO 13485: Device Companies Have Three Years to Transition. Available at http://raps.org/Regulatory-Focus/News/2016/03/01/24443/New-ISO-13485-Device-Companies-Have-Three-Years-to-Transition/ [accessed 29.07.2016].

- 31.Yin Paul C. 2015. The critical points of enterprise valuation. Chinese Innovative Medical Device Forum, Taipei, Taiwan. [Google Scholar]