Carbonic anhydrase II microcrystals suitable for XFEL data collection diffracted to 1.7 Å resolution and were indexed in space group P21, with unit-cell parameters a = 42.2, b = 41.2, c = 72.0 Å, β = 104.2°.

Keywords: X-ray free-electron lasers, XFELs, serial femtosecond crystallography, time-resolved crystallography, microcrystals, carbonic anhydrase II

Abstract

Recent advances in X-ray free-electron laser (XFEL) sources have permitted the study of protein dynamics. Femtosecond X-ray pulses have allowed the visualization of intermediate states in enzyme catalysis. In this study, the growth of carbonic anhydrase II microcrystals (40–80 µm in length) suitable for the collection of XFEL diffraction data at the Pohang Accelerator Laboratory is demonstrated. The crystals diffracted to 1.7 Å resolution and were indexed in space group P21, with unit-cell parameters a = 42.2, b = 41.2, c = 72.0 Å, β = 104.2°. These preliminary results provide the necessary framework for time-resolved experiments to study carbonic anhydrase catalysis at XFEL beamlines.

1. Introduction

Over the last decade, the development of X-ray free-electron lasers (XFELs) has presented new opportunities for experiments in the field of structural biology. With a peak spectral brightness many orders of magnitude higher than a third-generation synchrotron source, and X-ray pulses on the femtosecond timescale, XFEL studies can produce useful diffraction from nanocrystals at room temperature (RT) before the crystal becomes subject to radiation damage (Chapman et al., 2011 ▸). As the time resolution of synchrotron sources is limited to ∼100 ps, a femtosecond X-ray pulse provides a means to measure biological reactions that typically occur within picoseconds. Furthermore, the collection of diffraction data at RT is important for the visualization of reaction intermediates, as cryogenic temperatures have been shown to restrict the occupancy of alternate conformational states (Fraser et al., 2009 ▸). Thus, serial femtosecond crystallography (SFX) provides the ability to generate ‘molecular movies’ of enzyme catalytic mechanisms (Spence, 2017 ▸).

The emergence of SFX and XFELs in conjunction with photoactivation strategies allows the study of protein dynamics and kinetics in real time, which has been demonstrated in studies of photosystems I and II, myoglobin, photoactive yellow protein (PYP) and bacteriorhodopsin (Nango et al., 2016 ▸; Pande et al., 2016 ▸; Suga et al., 2017 ▸; Kupitz et al., 2014 ▸; Levantino et al., 2015 ▸). In previous Laue pump–probe time-resolved experiments, large-scale crystals were needed and achieved only 10–12% reaction initiation, whereas ∼40% photoconversion was achieved upon direct exposure of PYP microcrystals to the X-ray beam (Tenboer et al., 2014 ▸). The diffraction-before-destruction aspect of SFX and the tendency for low hit rates during data collection therefore demands large volumes of microcrystals for the collection of a complete data set (Chapman et al., 2011 ▸). Furthermore, the microcrystals must be homogenous in size not only to aid delivery but also to ensure uniform photoactivation.

Carbonic anhydrase II (CA II), a zinc metalloenzyme that catalyzes the reversible hydration of CO2, is one of the fastest known enzymes, with a k cat of 106 s−1 (Steiner et al., 1975 ▸). This reaction follows a classic two-step ping-pong enzymatic mechanism. In the hydration direction, a zinc-bound hydroxide performs a nucleophilic attack on CO2, resulting in a zinc-bound HCO3 − product that is subsequently displaced by a water molecule. The zinc-bound solvent is regenerated through a proton-transfer mechanism facilitated by a histidine residue at the entrance to the active site (Boone et al., 2014 ▸).

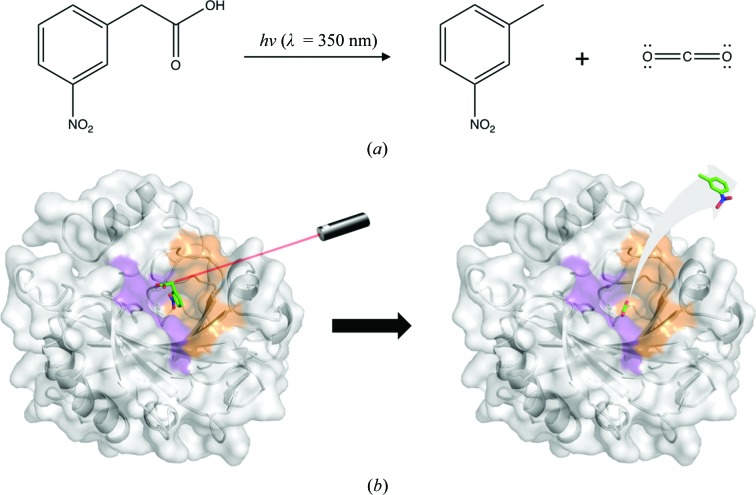

Although this reaction has been extensively studied and X-ray crystal structures of CA II in complex with substrate and product have been elucidated, there is still little structural information regarding the dynamics of the catalytic mechanism (Domsic et al., 2008 ▸; Domsic & McKenna, 2010 ▸; Kim et al., 2016 ▸, 2018 ▸; Fierke et al., 1991 ▸). Hence, the use of pump–probe, time-resolved SFX (TR-SFX) would be the preferred methodology to visualize the pathways of substrate/product entry/exit from the active site. This can be achieved using photoactivatable compounds such as 3-nitrophenylacetic acid (3NPAA), which releases CO2 upon photolysis (λ = 350 nm; Figs. 1 ▸ a and 1 ▸ b). Therefore, CA II is an excellent candidate for the use of SFX–XFEL studies.

Figure 1.

(a) Scheme for CO2 generation via photolysis of 3NPAA. (b) Surface representation of CA II in complex with 3NPAA (unpublished data) which can be activated with a 350 nm laser pulse to free CO2.

Here, we demonstrate the production of CA II microcrystals suitable for the collection of XFEL diffraction data and present preliminary XFEL data and processing results.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Macromolecule production

The expression and purification of CA II were performed as described previously (Tanhauser et al., 1992 ▸; Pinard et al., 2013 ▸). In brief, CA II was expressed in Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) competent cells via IPTG induction (Table 1 ▸). The protein was then purified using affinity chromatography with p-(aminomethyl)-benzenesulfonamide resin. The purity was verified by SDS–PAGE and the concentration was determined via UV–Vis spectroscopy.

Table 1. Macromolecule-production information.

| Source organism | Homo sapiens |

| Expression vector | pET31F1+ |

| Expression host | E. coli |

| Complete amino-acid sequence | MSHHWGYGKHNGPEHWHKDFPIAKGERQSPVDIDTHTAKYDPSLKPLSVSYDQATSLRILNNGHAFNVEFDDSQDKAVLKGGPLDGTYRLIQFHFHWGSLDGQGSEHTVDKKKYAAELHLVHWNTKYGDFGKAVQQPDGLAVLGIFLKVGSAKPGLQKVVDVLDSIKTKGKSADFTNFDPRGLLPESLDYWTYPGSLTTPPLLECVTWIVLKEPISVSSEQVLKFRKLNFNGEGEPEELMVDNWRPAQPLKNRQIKASFK |

2.2. Crystallization

Crystals of CA II were grown at 298 K using the hanging-drop vapor-diffusion method with a precipitant solution consisting of 1.6 M sodium citrate, 50 mM Tris pH 7.8. Upon visual inspection, a single high-quality crystal (∼200 × 50 × 50 µm) was transferred from the crystal drop into a new 10 µl drop of precipitant solution and crushed using a needle. The needle was then immersed into a secondary 10 µl droplet of precipitant solution to dilute the crystals and create a CA II seed stock.

CA II microcrystals were grown at 298 K utilizing a combination of seeding and batch crystallization methods by adding CA II seed stock and purified protein directly to the precipitant solution. In a 24-well culture plate, 5 µl seed stock, 300 µl CA II (30 mg ml−1) and 1200 µl precipitant solution were added to each well as described previously (Mahon et al., 2016 ▸). Microcrystal growth was observed after 12 h. The microcrystal suspension was diluted in precipitant solution (1:4 ratio) and syringe-filtered through a metal filter, removing crystals of greater than 100 µm in length. After five successive filtrations, the microcrystal suspension was concentrated by centrifugation at ∼840g for 5 min. The microcrystals were then mixed with monoolein (100%, Hampton Research) in a 1:1 ratio in gas-tight syringes and transferred into a lipid cubic phase (LCP) injector (Weierstall et al., 2014 ▸) for data collection.

2.3. Data collection and processing

Diffraction data were collected at the Coherent X-ray Imaging (CXI) station at Pohang Accelerator Laboratory XFEL (PAL-XFEL; Kang et al., 2017 ▸). The CXI station at PAL-XFEL is specifically designed for SFX and time-resolved SFX experiments, with Kirkpatrick–Baez (KB) mirrors for ∼2 µm microfocusing, an LCP injector system for microcrystal delivery, an optical (pump) femtosecond laser and capabilities to collect data at a 60 Hz repetition rate. For our data collection, we utilized single-shot X-ray pulses at 10 Hz and a microfocus of 5 µm diameter. The X-ray pulse widths were 20 fs at 1.2 × 1011 photons per pulse (photon energy = 9.715 keV). The subsequent X-ray diffraction data were collected on a Rayonix detector with a readout rate of 10 Hz. The microcrystal suspension in monoolein allowed sample injection using an isocratic flow mode at a flow rate of 150 nl min−1. The injector diameter was 100 µm and the sample-to-detector distance was 130 mm.

Three methods of data pre-processing were tested with NanoPeakCell: methods A, B and C using images containing more than ten detector pixels with I > 10 000, I > 5000 and I > 1000, respectively (Coquelle et al., 2015 ▸). CrystFEL was utilized for data indexing using the peakfinder8 and MOSFLM functions (White et al., 2012 ▸).

3. Results and discussion

The batch crystallization method, in which purified CA II was directly mixed with precipitant solution, resulted in only a few CA II crystals (Fig. 2 ▸ a). Hence, this method alone was inadequate for producing the large volumes of crystals necessary for XFEL experiments and delivery via an LCP injector. Therefore, microcrystals were grown via seeding in conjunction with batch crystallization, promoting multiple crystal nucleation points (Fig. 2 ▸ b). As this method resulted in a mixture of crystal sizes, syringe-driven filtration was used to exclude larger crystals, resulting in crystals ranging between 40 and 80 µm in size. The microcrystal suspension was combined with monoolein as a homogenous mixture that was effectively injected via an LCP injector without clogging.

Figure 2.

(a) CA II crystals grown via batch crystallization. (b) CA II microcrystals grown by combining seeding and batch crystallization techniques.

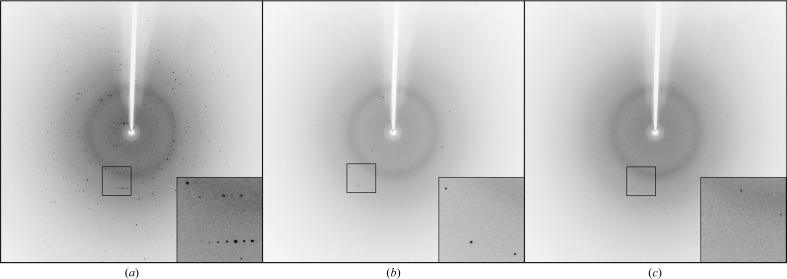

The CA II microcrystals were shown to diffract to a maximal resolution of 1.7 Å and belonged to space group P21, with unit-cell parameters a = 42.2, b = 41.2, c = 72.0 Å, β = 104.2° (Fig. 3 ▸). A total of 380 000 images were collected in 4 h, of which 199, 812 and 15 996 images were selected during pre-processing using methods A, B and C, respectively. This resulted in hit rates of 0.05, 0.21 and 4.21%, respectively (Table 2 ▸).

Figure 3.

XFEL diffraction of CA II microcrystals. Representative images of the data used for methods A, B and C with more than ten detector pixels with I > 10 000, I > 5000 and I > 1000, respectively.

Table 2. XFEL diffraction data statistics.

Values in parentheses are for the outer shell.

| Method | A | B | C |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wavelength (keV) | 9.715 | ||

| X-ray focus (µm) | 5 × 5 | ||

| Pulse energy/fluence at sample (photons per pulse) | 1.2 × 1011 | ||

| Space group | Monoclinic, P21 | ||

| Unit-cell parameters (Å, °) | a = 42.2, b = 41.2, c = 72.0, β = 104.2 | ||

| Total No. of images | 380 000 | ||

| No. of sorted images | 199 | 812 | 15996 |

| No. of indexed images | 190 | 782 | 9629 |

| No. of unique reflections | 5856 | 19024 | 24451 |

| Resolution limits (Å) | 69.8–1.7 (1.74–1.70) | ||

| Completeness (%) | 23.0 (6.9) | 74.6 (35.0) | 99.8 (98.3) |

| 〈I/σ(I)〉 | 5.2 (5.0) | 4.5 (2.1) | 2.4 (1.1) |

| R split † | 0.965 | 0.830 | 0.366 |

| Wilson B factor (Å2) | 18.2 | 23.5 | 29.3 |

| R.m.s.d., bonds (Å) | 0.011 | 0.011 | 0.013 |

| R.m.s.d., angles (°) | 1.58 | 1.58 | 1.74 |

R

split =

(White et al., 2012 ▸).

(White et al., 2012 ▸).

Overall, these experiments demonstrate the successful growth of CA II microcrystals suitable for XFEL data collection. Furthermore, our diffraction data confirm the feasibility of pump–probe TR-SFX experiments to study the catalytic mechanism of CA II in conjunction with photoactivatable compounds.

Acknowledgments

The experiment was performed on the NCI beamline of PAL-XFEL. The authors would like to acknowledge the expertise and guidance provided by the PAL-XFEL experimental staff.

Funding Statement

This work was funded by National Research Foundation of Korea grants 2014R1A2A1A11051254 and 2016R1A5A1013277.

References

- Boone, C. D., Pinard, M., McKenna, R. & Silverman, D. (2014). Carbonic Anhydrase: Mechanism, Regulation, Links to Disease, and Industrial Applications, edited by S. C. Frost & R. McKenna, pp. 31–52. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Chapman, H. N. et al. (2011). Nature (London), 470, 73–77.

- Coquelle, N., Brewster, A. S., Kapp, U., Shilova, A., Weinhausen, B., Burghammer, M. & Colletier, J.-P. (2015). Acta Cryst. D71, 1184–1196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Domsic, J. F., Avvaru, B. S., Kim, C. U., Gruner, S. M., Agbandje-McKenna, M., Silverman, D. N. & McKenna, R. (2008). J. Biol. Chem. 283, 30766–30771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Domsic, J. F. & McKenna, R. (2010). Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1804, 326–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Fierke, C. A., Calderone, T. L. & Krebs, J. F. (1991). Biochemistry, 30, 11054–11063. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Fraser, J. S., Clarkson, M. W., Degnan, S. C., Erion, R., Kern, D. & Alber, T. (2009). Nature (London), 462, 669–673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kang, H.-S. et al. (2017). Nat. Photon. 11, 708–713.

- Kim, C. U., Song, H., Avvaru, B. S., Gruner, S. M., Park, S. & McKenna, R. (2016). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 113, 5257–5262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kim, J. K., Lomelino, C. L., Avvaru, B. S., Mahon, B. P., McKenna, R., Park, S. & Kim, C. U. (2018). IUCrJ, 5, 93–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kupitz, C. et al. (2014). Nature (London), 513, 261–265.

- Levantino, M., Schirò, G., Lemke, H. T., Cottone, G., Glownia, J. M., Zhu, D., Chollet, M., Ihee, H., Cupane, A. & Cammarata, M. (2015). Nature Commun. 6, 6772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Mahon, B. P., Kurian, J. J., Lomelino, C. L., Smith, I. R., Socorro, L., Bennett, A., Hendon, A. M., Chipman, P., Savin, D. A., Agbandje-McKenna, M. & McKenna, R. (2016). Cryst. Growth Des. 16, 6214–6221.

- Nango, E. et al. (2016). Science, 354, 1552–1557. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Pande, K. et al. (2016). Science, 352, 725–729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Pinard, M. A., Boone, C. D., Rife, B. D., Supuran, C. T. & McKenna, R. (2013). Bioorg. Med. Chem. 21, 7210–7215. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Spence, J. C. H. (2017). IUCrJ, 4, 322–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Steiner, H., Jonsson, B. H. & Lindskog, S. (1975). Eur. J. Biochem. 59, 253–259. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Suga, M. et al. (2017). Nature (London), 543, 131–135.

- Tanhauser, S. M., Jewell, D. A., Tu, C. K., Silverman, D. N. & Laipis, P. J. (1992). Gene, 117, 113–117. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Tenboer, J. et al. (2014). Science, 346, 1242–1246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Weierstall, U. et al. (2014). Nature Commun. 5, 3309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- White, T. A., Kirian, R. A., Martin, A. V., Aquila, A., Nass, K., Barty, A. & Chapman, H. N. (2012). J. Appl. Cryst. 45, 335–341.