Loss-of-function mutations of the human postsynaptic cell-adhesion protein neuroligin-4 have been repeatedly associated with autism, but the precise synaptic function of neuroligin-4 that may account for its role in autism remains unclear. Here, we show in murine brainstem synapses that neuroligin-4 is selectively required for glycinergic synaptic transmission in mice.

Abstract

In human patients, loss-of-function mutations of the postsynaptic cell-adhesion molecule neuroligin-4 were repeatedly identified as monogenetic causes of autism. In mice, neuroligin-4 deletions caused autism-related behavioral impairments and subtle changes in synaptic transmission, and neuroligin-4 was found, at least in part, at glycinergic synapses. However, low expression levels precluded a comprehensive analysis of neuroligin-4 localization, and overexpression of neuroligin-4 puzzlingly impaired excitatory but not inhibitory synaptic function. As a result, the function of neuroligin-4 remains unclear, as does its relation to other neuroligins. To clarify these issues, we systematically examined the function of neuroligin-4, focusing on excitatory and inhibitory inputs to defined projection neurons of the mouse brainstem as central model synapses. We show that loss of neuroligin-4 causes a profound impairment of glycinergic but not glutamatergic synaptic transmission and a decrease in glycinergic synapse numbers. Thus, neuroligin-4 is essential for the organization and/or maintenance of glycinergic synapses.

Introduction

Autism spectrum disorders (ASDs) are characterized by profound alterations in social and communicative interactions, restricted interests, and repetitive and stereotyped behaviors (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Epidemiological studies showed that ASDs affect ∼0.7–1.1% of the population and are four to five times more frequent in males than females (Elsabbagh et al., 2012). Concordance rates are ∼82–92% in monozygotic twins and ∼1–10% in dizygotic twins (Folstein and Rutter, 1977; Bailey et al., 1995), indicating that ASDs have a strong genetic component. Several genes, including the gene encoding neuroligin-4 (NLGN4), have been associated with ASDs (Jamain et al., 2003; Laumonnier et al., 2004; Yan et al., 2005; Talebizadeh et al., 2006; Lawson-Yuen et al., 2008; Daoud et al., 2009; Pampanos et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2009; Xu et al., 2014; Chanda et al., 2016; Landini et al., 2016; Nakanishi et al., 2017; Südhof, 2017). Neuroligin-4 belongs to the neuroligin family of neuronal cell-adhesion proteins (Ichtchenko et al., 1995; Bolliger et al., 2001). Neuroligin-4 KO mice exhibit behavioral changes that resemble the core symptoms of ASD, including impaired social interactions, deficient ultrasound vocalizations, and increased repetitive behaviors (Jamain et al., 2008; Ey et al., 2012; El-Kordi et al., 2013; Ju et al., 2014), indicating that the neuroligin-4 KO represents a useful mouse model for ASDs. However, the synaptic functions of neuroligin-4 are incompletely understood.

Neuroligin-4 is expressed throughout the mouse brain. Immunocytochemistry revealed a faint and diffuse distribution of neuroligin-4 in the forebrain and robust punctate neuroligin-4 signals colocalizing with markers of inhibitory synapses in most other brain regions (e.g., retina, brainstem, and spinal cord; Jamain et al., 2008; Hoon et al., 2011). The neuroligin-4 KO caused subtle deficits of glycinergic synaptic transmission in the retina (Hoon et al., 2011), subtle reductions of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA)ergic synaptic transmission in mouse hippocampal CA3 neurons along with aberrant γ oscillations in the hippocampal CA3 region (Hammer et al., 2015), increased power in the α frequency band of spontaneous network activity in the barrel cortex, and a reduced presynaptic vesicle pool size and release probability at GABAergic and glutamatergic synapses in the cortex (Unichenko et al., 2017). In contrast to the deletion of neuroligin-4 in mice, overexpression of neuroligin-4 in cultured hippocampal neurons puzzlingly reduced glutamatergic but not GABAergic synaptic transmission (Zhang et al., 2009; Chanda et al., 2016).

The complex and partially contradictory character of the available information on the role of neuroligin-4 in synapses prompted us to examine its function in an anatomically and functionally well-defined neuronal circuit, the medial nucleus of the trapezoid body (MNTB), whose cells abundantly express neuroligin-4 (Hoon et al., 2011). MNTB principal neurons receive four synaptic inputs: (1) a giant excitatory glutamatergic synapse, the calyx of Held, which originates from the ventral cochlear nucleus (von Gersdorff and Borst, 2002; Borst and Soria van Hoeve, 2012; Yu and Goodrich, 2014), (2) sparse noncalyceal excitatory inputs (Hamann et al., 2003), (3) multiple inhibitory inputs primarily from the ipsilateral ventral nucleus of the trapezoid body (Albrecht et al., 2014), and (4) local inhibitory inputs originating from within the MNTB (Kuwabara et al., 1991). Interestingly, the inhibitory inputs to MNTB principal neurons shift from GABAergic to glycinergic neurotransmission during development, such that at P11 most inhibitory inputs are glycinergic (Awatramani et al., 2004, 2005). Both inhibitory and excitatory transmission at MNTB principal neurons become faster and stronger with age, thereby acquiring the ability to mediate high-frequency synaptic transmission with high precision and fidelity (von Gersdorff and Borst, 2002; Awatramani et al., 2004, 2005). Using the MNTB brain slice preparation that we previously used for studies of other neuroligins (Zhang et al., 2017), we now show that loss of neuroligin-4 causes a profound and selective reduction in glycinergic synaptic transmission and in the number of glycinergic synapses at MNTB principal cells without impairing excitatory synaptic transmission. Our findings reveal a previously unappreciated role of neuroligin-4 in the maintenance of glycinergic synapses in an intact neuronal circuit in vivo.

Results and discussion

Neuroligin-4 is essential for glycinergic synaptic transmission at MNTB principal neurons

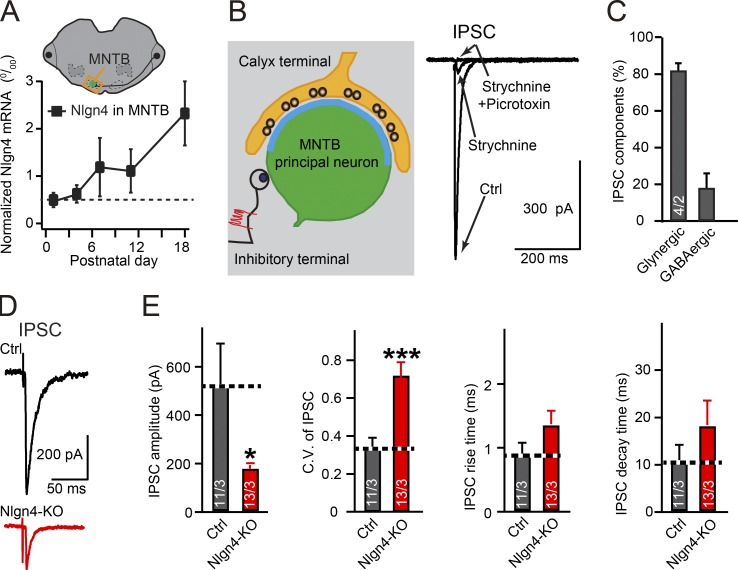

To assess the role of neuroligin-4 in MNTB principal neurons, we first analyzed the developmental expression of neuroligin-4 in the MNTB. Using quantitative RT-PCR from carefully dissected MNTB tissue samples, we found that neuroligin-4 mRNA levels slightly increase from postnatal day (P) 0 to P12 and robustly increase from P12 to P18 (Fig. 1 A), indicating a prominent role of neuroligin-4 in the MNTB after P11.

Figure 1.

Neuroligin-4 KO impairs glycinergic inhibitory synaptic transmission in principal neurons of the MNTB. (A) Measurements of neuroligin-4 mRNA levels from dissected MNTB during development (from P1 to P18, normalized to actin). (B) Illustration of recording strategy from MNTB neurons (left) and sample traces of IPSCs recorded in the absence or presence of strychnine or strychnine and picrotoxin (right). (C) Summary graph of the percentage of the IPSC amplitude that is sensitive to 1 µM strychnine (glycinergic) or to picrotoxin (GABAergic), as recorded from the MNTB of P13–P14 WT mice. (D and E) Sample traces (D) and summary graphs (E) of IPSCs recorded from P14–16 MNTB neurons from littermate control (Nlgn123fl/fl; Nlgn4+/+, gray) and neuroligin-4 KO mice (Nlgn123fl/fl; Nlgn4−/−, red). Data are means ± SEM. Numbers in bars represent the number of cells per the number of mice examined. Statistical significance was determined by Student’s t test (*, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001). Ctrl, control.

Using acute slices, we next performed patch-clamp recordings of inhibitory synaptic responses in principal neurons of the MNTB. Consistent with previous findings (Awatramani et al., 2004, 2005), we found that at P13–14, an age at which MNTB synapses are relatively mature, >80% of evoked inhibitory postsynaptic currents (IPSCs) recorded from MNTB principal neurons were blocked by the glycine receptor (GlyR) blocker strychnine and were thus glycinergic (Fig. 1, B and C).

These data indicate that the MNTB is ideally suited to examine a potential role for neuroligin-4 in glycinergic versus glutamatergic synaptic transmission. Toward this end, we assessed synaptic responses elicited by stimulation of single axons synapsing onto MNTB principal neurons, using acute slices from P14 to P16 mice. We adjusted the stimulus intensity to obtain a >60% failure rate, a condition under which the probability of an IPSC in the MNTB neuron being evoked by multiple axon inputs is low (Awatramani et al., 2004, 2005). With this minimal stimulation protocol, we found that the neuroligin-4 KO reduced IPSC amplitudes to ∼35% of control amplitudes without affecting the rise and decay times of IPSCs (Fig. 1, D and E). Under these conditions, the neuroligin-4 KO did not significantly reduce strychnine-insensitive IPSC amplitudes (Fig. S1). These data indicate that neuroligin-4 is critical for glycinergic strychnine-sensitive, but not GABAergic, strychnine-insensitive inhibitory synaptic transmission in MNTB neurons. Here, neuroligin-4 could perform possible functions (1) in maintaining the presynaptic release probability, (2) in organizing the postsynaptic receptor content, and/or (3) in maintaining the number of synapses.

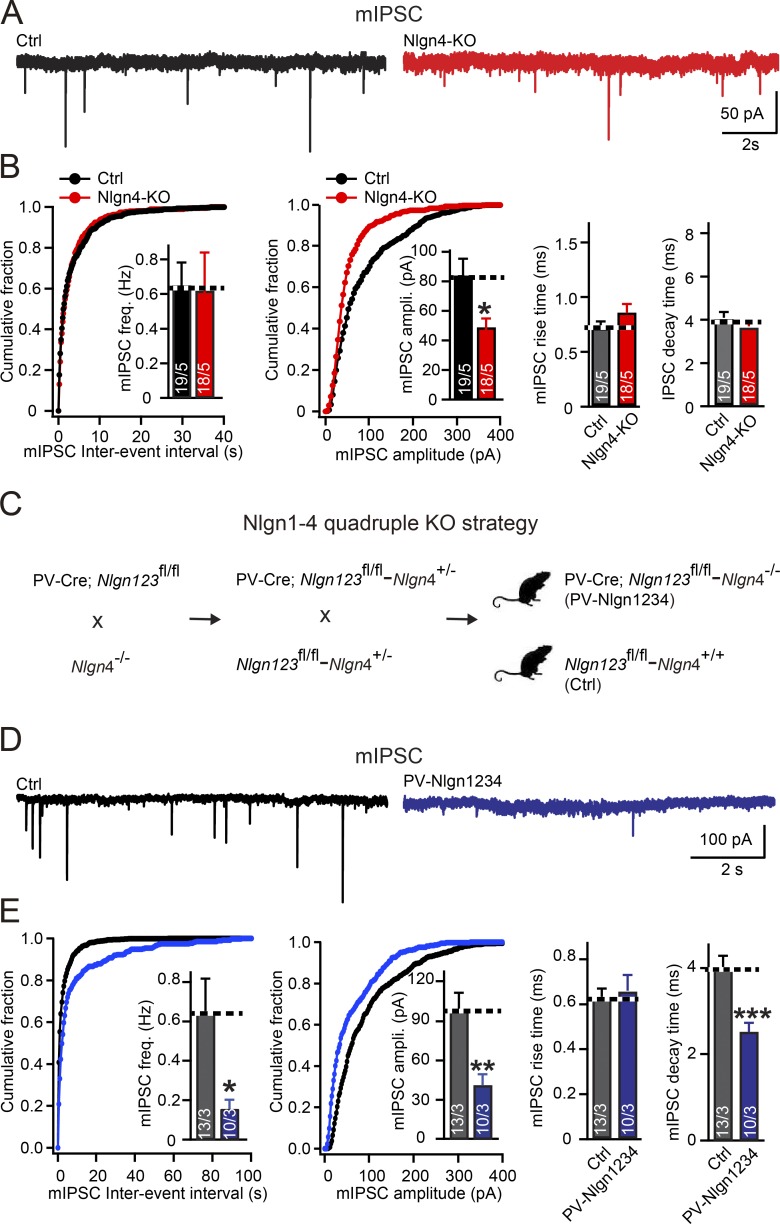

To distinguish between these possibilities, we first analyzed the coefficient of variation of IPSC amplitudes, which depends largely but not exclusively on the presynaptic release probability. We uncovered a 100% increase in the coefficient of variation in neuroligin-4 KO MNTB principal neurons compared with control cells (Fig. 1, D and E). Although according to classical quantal analysis, this result indicates a decrease in presynaptic release probability (Bekkers and Stevens, 1995), it could also potentially be because of an abnormal content or distribution of postsynaptic GlyRs, as suggested by studies in glutamatergic synapses (Faber et al., 1992; Heine et al., 2008). To further explore the synaptic abnormalities in neuroligin-4 KO mice, we examined postsynaptic receptor content by measuring miniature IPSCs (mIPSCs). The mIPSC frequency broadly correlates with release probability (and other parameters), whereas the mIPSC amplitude is a measure of postsynaptic receptor content, providing an independent set of parameters to examine the cause of the massive decrease in glycinergic transmission induced by the neuroligin-4 KO. Because the mIPSC frequency in MNTB neurons was too low for accurate measurements in the presence of the standard 2 mM extracellular Ca2+ and glycinergic synapses in the MNTB appear to exhibit little multivesicular release at higher Ca2+ concentrations (Lim et al., 2003), we increased the mIPSC frequency by elevating extracellular Ca2+ from 2 mM to 10 mM. We found that under these conditions, the neuroligin-4 KO did not alter mIPSC frequency. Moreover, the neuroligin-4 KO caused a reduction in mIPSC amplitude (to ∼65% of control values) that was highly significant because of the reproducibility of mIPSC amplitude measurements but did not alter the rise and decay times of mIPSCs (Fig. 2, A and B). These data, viewed together, indicate that the loss of neuroligin-4 robustly decreases inhibitory glycinergic synaptic transmission in MNTB principal neurons primarily by reducing the postsynaptic receptor content.

Figure 2.

Neuroligin-4 KO significantly decreases the amplitude of mIPSCs in MNTB neurons, whereas the quadruple KO of all neuroligins decreases both the amplitude and frequency of mIPSCs. (A and B) Sample traces (A) and summary data (B) of mIPSCs recorded from P14–P16 MNTB neurons in acute slices from littermate control (Nlgn123fl/fl; Nlgn4+/+, black) and neuroligin-4 KO mice (Nlgn123fl/fl; Nlgn4−/−, red). Summary data include cumulative plots of the mIPSC interevent interval and amplitude, with inserts depicting summary graphs of the mIPSC frequency and amplitude (left and center plots, respectively) and measurements of the mIPSC rise and decay times (right summary graphs). (C) Illustration of breeding strategy to achieve early postnatal ablation of neuroligins in MNTB neurons by crossing mice containing all floxed alleles of neuroligin-1, neuroligin-2, and neuroligin-3 (Nlgn123fl/fl) and a PV-Cre driver allele with mice containing the constitutive neuroligin-4 KO (Nlgn4 KO). Mice with positive PV-Cre transgene, Nlgn123 conditional floxed alleles and neuroligin-4 KO mice were termed PV-Nlgn1234, and littermate mice with negative PV-Cre transgene, Nlgn123 conditional floxed alleles, and WT neuroligin-4 alleles were used as control. (D) Samples traces of mIPSC recorded from P14–16 MNTB neurons from control (Nlgn123fl/fl; Nlgn4+/+, gray) and PV-Nlgn1234 (PV-Cre+/−; Nlgn123fl/fl; Nlgn4−/−, blue) littermates. (E) Summary graph of mIPSC recorded from P14–16 MNTB neurons from control (Nlgn123fl/fl; Nlgn4+/+, gray) and PV-Nlgn1234 (PV-Cre+/−; Nlgn123fl/fl; Nlgn4−/−, blue) littermates. Summary data include cumulative plots of the mIPSC interevent interval and amplitude, with inserts depicting summary graphs of the mIPSC frequency and amplitude (left and center plots, respectively) and measurements of the mIPSC rise and decay times (right summary graphs). Data are means ± SEM. The numbers in bars represent the number of cells per the number of mice used. Statistical significance was determined by Student’s t test (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001). Ctrl, control.

We next asked whether other neuroligins contribute to glycinergic synaptic transmission in MNTB principal neurons. To address this question, we examined glycinergic synaptic responses after deletion of all neuroligins. Previous studies validated the efficiency of parvalbumin (PV)-driven Cre expression to delete floxed alleles in MNTB neurons at P12 (Zhang et al., 2017). Therefore, we crossed previously generated PV-neuroligin-1/2/3 triple-KO mice (Zhang and Südhof, 2016) with neuroligin-4 KO mice to delete all neuroligins in MNTB neurons (PV–neuroligin-123–neuroligin-4 KO, termed PV-Nlgn1234; Fig. 2 C). We then studied the effects of the pan-neuroligin deletion in glycinergic synapses of MNTB principal neurons between P14 and P16 and compared these effects to those of the neuroligin-4 KO. As before, we recorded mIPSCs in the presence of 1 mM tetrodotoxin (TTX) at a high extracellular Ca2+concentration (10 mM). Strikingly, we found that the pan-neuroligin deletion reduced the mIPSC frequency (to ∼25% of controls) and additionally further decreased the mIPSC amplitude (to ∼40% of controls; Fig. 2, D and E). Kinetic analyses again revealed no change in mIPSC rise times in PV-Nlgn1234 neurons but uncovered shorter mIPSC decay times (Fig. 2, D and E), indicating possible changes in subunit composition and/or mislocalization of GlyRs. This conclusion was strengthened by recordings of mIPSCs in MNTB neurons from pan-neuroligin quadruple-KO mice that were performed in the presence of 2 mM Ca2+, a more physiological concentration (Fig. S1). Specifically, in these mice, we detected the same mIPSC phenotype in 2 mM Ca2+ as in 10 mM Ca2+, demonstrating that the high Ca2+ concentration in itself did not elicit or distort the mIPSC phenotype. Thus, other neuroligins besides neuroligin-4 contribute to inhibitory transmission at glycinergic synapses in MNTB principal neurons. No change of mIPSC in PV-Nlgn123 (Fig. S1) suggested that the contributions of neuroligin-1 to -3 to glycinergic transmission become manifest only in the absence of neuroligin-4 KO.

Neuroligin-4 is required for the maintenance of glycinergic synapses at MNTB principal neurons

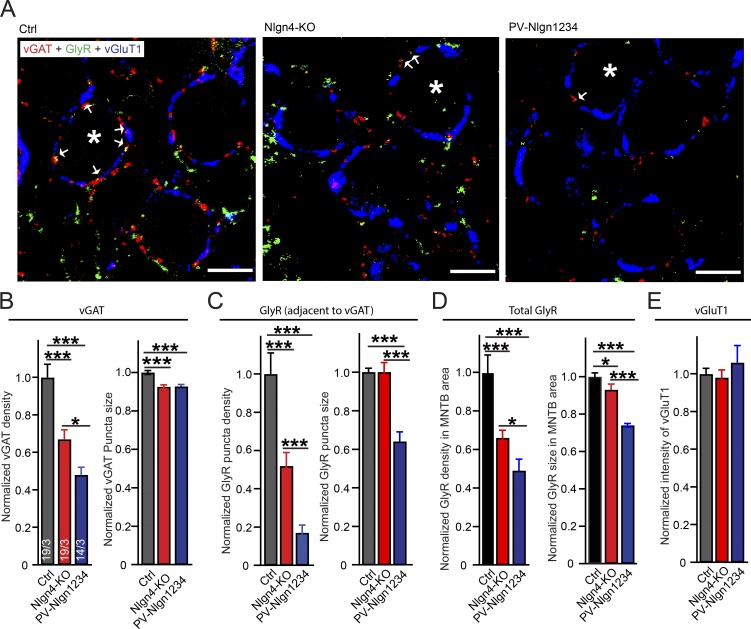

We next tested whether the neuroligin-4 KO reduced glycinergic synaptic transmission at MNTB principal neurons by decreasing the number of glycinergic synapses and/or the levels of GlyRs. We labeled inhibitory presynaptic terminals in the MNTB by immunostaining with antibodies to vesicular GABA transporter (vGAT), which is present at both glycinergic and GABAergic terminals, and with a pan-GlyR antibody, which recognizes postsynaptic GlyR clusters.

We found that the neuroligin-4 KO caused a large reduction of the density of vGAT puncta (to ∼65% of controls) and that the PV-Nlgn1234 mice produced a further reduction in vGAT puncta density (to ∼50% of control values). Both the neuroligin-4 KO and PV-Nlgn1234 similarly significantly reduced vGAT puncta size (to ∼90% of controls; Figs. 3, A and B; and S2). Because most GlyRs are tightly juxtaposed to vGAT-positive glycinergic nerve endings in MNTB principal neurons (Trojanova et al., 2014), we measured both GlyR signals adjacent to vGAT puncta next to the principal neurons of the MNTB and GlyR signals throughout the MNTB sections. We found that the neuroligin-4 KO significantly reduced the density of GlyR puncta that were adjacent to vGAT puncta (to ∼50% of controls), a reduction that is slightly higher than the reduction in inhibitory synapse density observed by labeling for vGAT itself. The pan-neuroligin KO (PV-Nlgn1234) further reduced the GlyR puncta density to ∼20% of control values in MNTB neurons. In addition, we found that PV-Nlgn1234, but not neuroligin-4 KO, reduced GlyR puncta size to ∼65% of control values (Fig. 3 C). To test whether neuroligin-4 plays a general role in the synaptic maintenance of GlyRs, we measured total GlyR puncta density in the whole MNTB field and found it to be reduced to ∼65% of control values in neuroligin-4 KOs and to be further reduced to ∼50% of control values in PV-Nlgn1234 (Fig. 3 D). This indicates a general role of neuroligin-4 in regulating GlyR levels and/or glycinergic synapse density.

Figure 3.

Neuroligin-4 KO and PV-Nlgn1234 quadruple KO reduce glycinergic synapse numbers in MNTB principal neurons. (A) Representative images revealing glycinergic synapses on the major projection neurons of the MNTB. Image depicts a single confocal plane of MNTB sections triple labeled by indirect immunofluorescence for the vGAT (red), glycine receptor (GlyR, green), and the vGluT1 (blue, to mark excitatory calyx synapses). Sections were from P15–P16 control (Nlgn123fl/fl; Nlgn4+/+), neuroligin-4 KO (Nlgn123fl/fl; Nlgn4−/−), and PV-Nlgn1234 (PV-Cre+/−; Nlgn123fl/fl; Nlgn4−/−) mice. Asterisks: MNTB principal neurons; arrows: vGAT/GlyR costained puncta. Bars, 5 µm. (B–D) Summary graphs of the density (left) and puncta size (right) of vGAT-positive synaptic puncta (B) and GlyR-positive puncta that are adjacent to vGAT-positive puncta (C), and GlyR-positive puncta independent of their relation to vGAT positive puncta (D). (E) Summary graph of the overall vGluT1 staining intensity. Note that because of the extended shape of the calyx of Held synapses containing vGluT1, no identification and quantification of separate puncta is possible (Fig. 5 H). Data are means ± SEM. Numbers in bars represent the number of images per the number of mice examined. Statistical significance was determined by single-factor ANOVA (*, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001). Ctrl, control.

In such measurements of presumptive synaptic puncta by immunocytochemistry, the puncta “size” is determined both by the amount of the targeted antigen in a synapse (e.g., in this case the GlyR content) and by the overall size of the synapse. Viewed together, the morphological and electrophysiological data demonstrate that neuroligin-4 is important for the control of glycinergic synapses and that other neuroligins further contribute to this control. The good correspondence between the reduction in evoked IPSC amplitude and glycinergic synapse numbers indicates that most of the neuroligin-4 KO phenotype is due to a loss of synapses.

In contrast to markers of inhibitory synapses, vesicular glutamate transporter 1 (vGluT1) immunofluorescence staining, which identifies excitatory terminals of calyx synapses, and the overall vGluT1-positive area were similar among the three genotypes tested (PV-Nlgn1234, neuroligin-4 KO, and control; Fig. 3 E), confirming previous conclusions that the deletion of neuroligins does not affect excitatory synapse numbers in the MNTB (Zhang et al., 2017).

Minimal changes in excitatory synaptic transmission at the calyx of Held synapse in neuroligin-4 KO mice

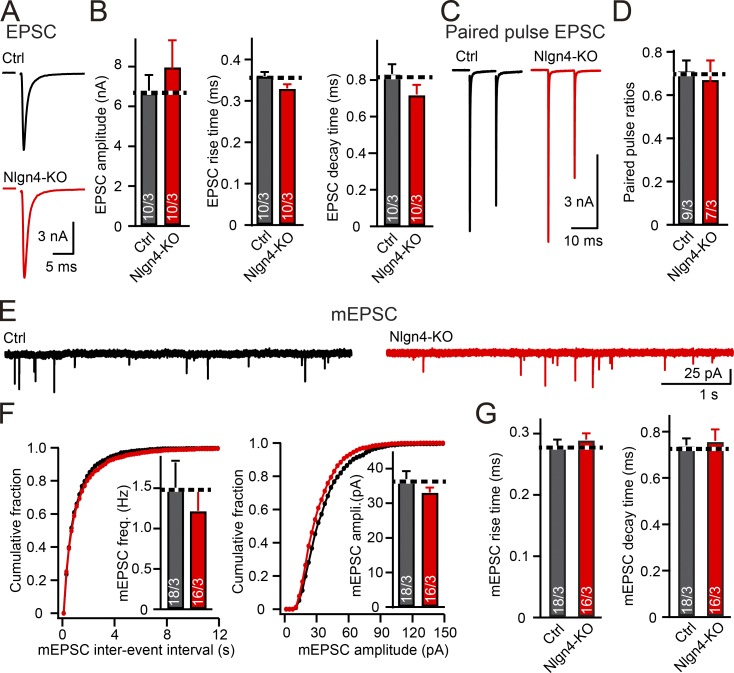

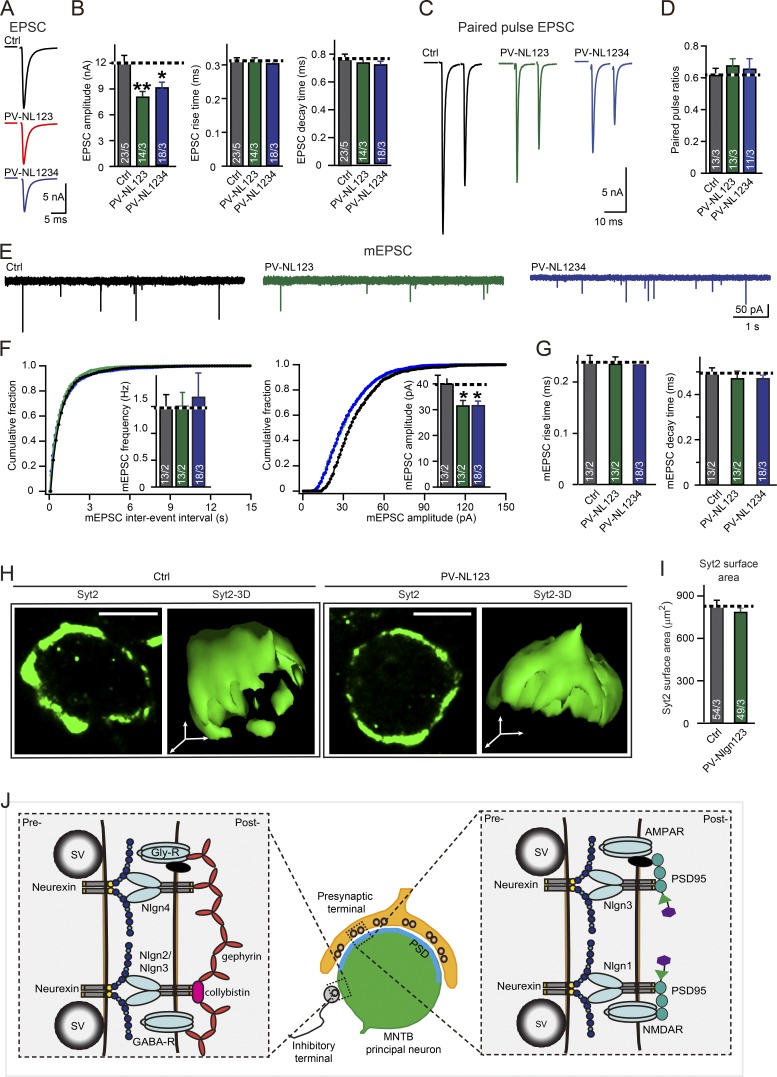

Neuroligin-4 was suggested to also contribute to glutamatergic synaptic transmission (Zhang et al., 2009; Delattre et al., 2013; Chanda et al., 2016; Unichenko et al., 2017), prompting us to test whether the neuroligin-4 KO affects excitatory synaptic transmission in MNTB principal neurons. Each MNTB principal neuron receives a giant excitatory input that forms the calyx of Held synapse (Hoffpauir et al., 2006). We measured excitatory synaptic transmission at calyx of Held synapses of neuroligin-4 KO and littermate control mice but found no changes. Specifically, the amplitude and kinetics of evoked excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) and the frequency, amplitude, and kinetics of miniature EPSCs (mEPSCs) were not significantly different between neuroligin-4 KO and control mice at ages between P12 and P14 (Fig. 4). Additionally, we found no change in paired-pulse ratios, indicating a normal presynaptic release probability at the calyx of Held in neuroligin-4 KO mice (Fig. 4, C and D). These data demonstrate that the neuroligin-4 KO does not alter excitatory synaptic transmission at calyx synapses.

Figure 4.

Neuroligin-4 KO does not affect excitatory synaptic transmission at the calyx of Held. (A and B) Evoked excitatory synaptic responses are unchanged by the neuroligin-4 KO (A, representative traces; B, summary graphs of the EPSC amplitude, rise times, and decay times). Recordings were made from patched MNTB principal neurons in response to extracellular fiber stimulation in acute slices from P12–P14 control (Nlgn123fl/fl; Nlgn4+/+, gray) and neuroligin-4 KO (Nlgn123fl/fl; Nlgn4−/−, red) mice. (C and D) Paired-pulse ratios of excitatory responses are unchanged by the neuroligin-4 KO (C, representative traces; D, summary graph for paired-pulse ratios at 10-ms interstimulus intervals. (E–G) Spontaneous miniature release is unchanged by the neuroligin-4 KO (E, representative traces; F, cumulative probability plots of the mEPSC interevent interval [left] or amplitude [right], with insets depicting summary graphs of the mEPSC frequency [left] or amplitude [right]; G, summary graphs of the mEPSC rise and decay times). Recordings were from P12–P14 MNTB neurons from control (black) and neuroligin-4 KO (red) littermate mice. Data are means ± SEM. Numbers in bars represent the number of cells per mice analyzed. Statistical significance was assessed by Student’s t test.

It is still possible, however, that neuroligin-4 redundantly contributes to excitatory synapses in MNTB principal neurons together with other neuroligins. We therefore tested the effect of the combined deletion of neuroligin-1/2/3/4 on excitatory synaptic transmission at the calyx of Held synapse. To be systematic, we measured AMPA receptor–mediated EPSCs and mEPSCs from PV-Nlgn1234, PV-Nlgn123, and respective littermate control mice. In both PV-Nlgn123 and PV-Nlgn1234 mice, EPSC amplitudes were reduced to ∼70% of control values and mEPSC amplitudes were decreased to ∼75% of control values (Figs. 5, A–F). This decrease was not associated with a change in synapse density or in the morphology of calyx terminals, as analyzed by immunostaining for synaptotagmin-2 as a specific presynaptic marker (Fig. 5, H and I; Sun et al., 2007). Viewed together, these results indicate that neuroligin-4 is dispensable for excitatory synaptic transmission at the calyx of Held synapse, because the observed impairments in EPSC and mEPSCs in PV-Nlgn1234 and PV-Nlgn123 are identical and likely originate from the deletion of neuroligin3 at the calyx of Held (Zhang et al., 2017).

Figure 5.

Quadruple Nlgn1234 KO does not further impair excitatory synaptic transmission in MNTB neurons that were observed in triple Nlgn123 KO. (A and B) Direct comparison of the effect of the triple Nlgn123 and the quadruple Nlgn1234 KO on evoked EPSCs in the calyx of Held synapse (A, representative traces; B, summary graphs of the EPSC amplitudes, rise times, and decay times). Recordings were made in acute slices from patched MNTB neurons in response to extracellular fiber stimulation; slices were from littermate control (Nlgn123fl/fl; Nlgn4+/+, gray), PV-Nlgn123 (PV-Cre+/−; Nlgn123fl/fl; Nlgn4+/+, green), and PV-Nlgn1234 (PV-Cre+/−; Nlgn123fl/fl; Nlgn4−/−, blue) mice at P12–14. (C and D) Neuroligin deletions have no effect on paired-pulse ratios at excitatory calyx of Held synapses (C, representative traces; D, summary graphs of paired-pulse ratios of EPSCs at 10-ms intervals). EPSCs were recorded from P12–14 MNTB neurons from control (gray), PV-Nlgn123 (green), and PV-Nlgn1234 (blue) littermates. (E–G) Neuroligin only modestly decreases the spontaneous mEPSC amplitude without affecting other mEPSC parameters (E, representative traces; F, cumulative probability plots of the mEPSC interevent interval [left] or amplitude [right], with insets depicting summary graphs of the mEPSC frequency [left] or amplitude [right]; G, summary graphs of the mEPSC rise and decay times). (H and I) Three-dimensional reconstructions of calyx of Held synapses immunolabeled for presynaptic structures by using antibodies to synaptotagmin-2 (Syt2, green) show that the Nlgn123 deletion has no effect on the overall size and structure of the calyx synapse (H, representative images of reconstructed calyces from 12-d-old PV-Nlgn123 and control mice [bars, 5 µm]; I, summary graph of the Syt2-labeled presynaptic surface area). (J) Model of neuroligin function at MNTB principal neurons. Neuroligin-1 is essential for NMDAR-mediated synaptic transmission (Jiang et al., 2017) at calyx of Heldneuroligin-3 is selectively essential for AMPA receptor–mediated synaptic transmission (Zhang et al., 2017), whereas neuroligin-2/3 and neuroligin-4 function primarily at inhibitory synapses onto principal neurons (Zhang et al., 2017, and this study). Interaction of neuroligins with receptors may be mediated by synaptic scaffolding proteins. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. The numbers in bars represent the number of cells per the number of mice used. Statistical significance was determined by single-factor ANOVA (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01). Ctrl, control.

In the present study, we analyzed the function of neuroligin-4 in excitatory and inhibitory synapses by studying the effect of the neuroligin-4 KO on excitatory and inhibitory synaptic inputs onto the principal neurons of the MNTB, which is a central component of a well-defined auditory circuit in the brainstem. We found that the neuroligin-4 KO caused a large decrease in the amplitude of glycinergic IPSCs and a proportionally smaller decrease in the amplitude of mIPSCs (Figs. 1 and 2). These phenotypes were largely due to a loss of glycinergic synapses (Fig. 3) and specific for inhibitory glycinergic synapses, indicating that neuroligin-4 is essential for glycinergic synapses in mice. Although the neuroligin-4 KO phenotype of glycinergic synapse loss was the most severe single-neuroligin deletion phenotype observed in a direct comparison of mutant mice, it was nevertheless exacerbated by additional deletion of other neuroligins, indicating that, similar to other synapses, multiple neuroligins redundantly contribute to the organization of glycinergic synapses (Figs. 2 and 3). Based on the present data and earlier immunolocalization results (Hoon et al., 2011), we thus propose that the major function of neuroligin-4 in mice is to mediate the formation and/or maintenance of glycinergic synapses, with the decrease in mIPSC amplitude suggesting that this function includes organizing postsynaptic glycinergic receptors. An overall view emerges whereby neuroligin-1 functions primarily in excitatory synapses, neuroligin-2 in GABAergic and cholinergic synapses, neuroligin-3 in both excitatory and inhibitory synapses, and neuroligin-4 in glycinergic synapses and probably also in at least some types of GABAergic synapses. The reduced glycinergic synaptic transmission observed here may at least partially account for some of the behavioral abnormalities in neuroligin-4 KO mice, consistent with the proposal that a glycinergic impairment may be involved in the etiology of ASDs (Pilorge et al., 2016).

Our data for the first time reveal an unequivocal essential function for neuroligin-4 in organizing glycinergic synapses in mice but are consistent with previous studies in retinal neurons and hippocampal CA3 pyramidal neurons, both of which showed no change in excitatory synaptic transmission upon neuroligin-4 loss (Hoon et al., 2011; Hammer et al., 2015). On the other hand, our data differ from the observations made in the somatosensory cortex, where loss of neuroligin-4 leads to a presynaptic deficit of glutamatergic transmission in a synaptic input-dependent manner (Unichenko et al., 2017). The reasons for these differences between the cortex and brainstem are unclear, but potential compensation by other neuroligins or even by members of other adhesion protein families (Hoon et al., 2011; Hammer et al., 2015; Unichenko et al., 2017) and the complexity of cortical circuits might complicate the interpretation of the specific function of neuroligin-4 at glutamatergic synapses. Instead, the well-characterized anatomy and function of the MNTB inputs allows for more straight-forward interpretations, which in the present case indicate—based on the data obtained with neuroligin-4 KO and PV-Nlgn1234 mice—that neuroligin-4 is not directly involved in the assembly, maintenance, and function of glutamatergic synapses. The neuroligin-4 KO in the retina results in a subtle reduction in the number of GlyR clusters and in the time course of glycinergic mIPSCs (Hoon et al., 2011). Although no data are available about the function of neuroligin-4 in glycinergic synaptic transmission in the cortex and hippocampus, it is possible that the impaired γ oscillations in the hippocampal CA3 region (Hammer et al., 2015) and the increased α-band power of spontaneous network activity in the cortex (Unichenko et al., 2017) of neuroligin-4 KO mice are caused not only by GABAergic defects but also by impaired glycinergic transmission at synaptic and/or extrasynaptic sites (Brackmann et al., 2004). Moreover, the fact that we observed no change in excitatory synaptic transmission in neuroligin-4-deficient neurons suggests that the decrease in excitatory synaptic transmission observed in mouse neurons after overexpression of neuroligin-4 is likely an overexpression effect (Zhang et al., 2009; Chanda et al., 2016). It is unclear, however, how these conclusions relate to human neuroligin-4. Although a comparable role for neuroligin-4 in mouse and human neurons is suggested by the overall conservation of neurexin-1 function in human neurons (Pak et al., 2015), the significant sequence differences between mouse and human neuroligin-4 suggest possible functional differences (Bolliger et al., 2008). Experiments with human neurons containing neuroligin-4 mutations will be required to address this important question.

Our data raise three major overall issues that partly already emerged in earlier studies on neuroligins. First, the neuroligin-4 KO phenotype described here can be best accounted for by a loss of glycinergic synapses as evidenced by (1) the decrease in IPSC amplitude and the (2) the corresponding decrease in the density of synaptic puncta immunolabeled by antibodies GlyRs or by vGAT. However, a simple loss of glycinergic synapses as a cause of the neuroligin-4 KO phenotype does not account for the decrease in mIPSC amplitude and the modest decrease in GlyR-staining intensity per synaptic punctum, which indicate that, in addition to causing a loss of glycinergic synapses, the neuroligin-4 KO decreases the GlyR content of the remaining glycinergic synapses, most likely affecting GlyRα1 as the predominantly expressed GlyR subunit (Hruskova et al., 2012). This conclusion is consistent with the observation that GlyRα1 clusters are also selectively reduced (by ∼16%) in neuroligin-4 KO retina (Hoon et al., 2011). In addition, the neuroligin-4 KO greatly increased the coefficient of variation in evoked IPSCs. Although such an increase traditionally is interpreted as indicative of a change in release probability, such an increase could conceivably reflect a change in the postsynaptic organization of GlyRs, i.e., could be caused by a disorganization of the alignment of postsynaptic GlyR clusters with presynaptic release sites. Interestingly, the additional deletion of all neuroligins did not simply enhance the neuroligin-4 KO phenotype at glycinergic synapses, but it changed this phenotype. Deletion of all neuroligins not only further decreased the density of glycinergic synapses, resulting in a loss of >80% of synapses but also reduced the GlyR content of the remaining synapses by >30%. Viewed together, these findings raise the question whether the loss of synapses and disorganization of GlyRs induced by neuroligin deletions reflect two independent functions of neuroligins or whether they are the consequence of a single central function of neuroligins in organizing glycinergic synapse.

Second, it is becoming increasingly clear that the genetic loss- or gain-of-function phenotypes induced by neuroligin-1 or -3 mutations at excitatory synapses never appear to produce a decrease in synapse numbers, whereas the loss-of-function phenotypes induced by neuroligin-2 or -4 mutations at inhibitory synapses often cause a decrease in synapse density, as observed here for neuroligin-4 and glycinergic synapses, or in the prefrontal cortex for neuroligin-2 and GABAergic synapses (Liang et al., 2015). This general observation is mirrored by neurexin mutations whereby deletion of neurexins caused a loss of a defined subset of inhibitory synapses (Chen et al., 2017).

Third, one cannot but wonder at the amazing functional diversity displayed by neuroligins, a family of four homologous proteins whose sequence similarity not only concerns their extracellular esterase-like domain that binds neurexins but also extends to their almost identical transmembrane regions and similar cytoplasmic tails. How do these very similar proteins that are coexpressed in the same neurons mediate such isoform-specific diverse functions? Exploring the molecular mechanisms involved is a major challenge that can only be met by studying specific actions of neuroligins by using genetic manipulations combined with in-depth experiments on the interactions of neuroligins with ligands other than neurexins, for example the MDGAs (Lee et al., 2013; Pettem et al., 2013).

Materials and methods

Animals

The following mouse lines were used: neuroligin-4 KO mice (Jamain et al., 2008), PV-Cre driver mice (Hippenmeyer et al., 2005), and neuroligin-1/2/3 triple conditional KO mice (Zhang et al., 2015; Zhang and Südhof, 2016). All analyses were performed on littermate mice for physiology (P12-P17), and in all analyses the experimenter was unaware of the genotype of the mice studied. Primers for neuroligin-4 genotyping were as follows: WT, 5′-CGGAATTGAGTGTAACAGGAC-3′ (466-bp product); KO, 5′-TTTGAGCACCAGAGGACATC-3′ (508-bp product); and common probe for both PCRs, 5′-CTTCCTATCCTGTTACTCTCACT-3′. All procedures conformed to National Institutes of Health Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Stanford University Administrative Panel on Laboratory Animal Care.

Quantitative RT-PCR

MNTB tissue from P1–18 mice was carefully dissected under a microscope as described (Zhang et al., 2017). RNA extractions were performed by using TRIzol reagent according to the manufacturer's protocol (Invitrogen). RNA was then quantified by using an ND-1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop; Thermo Fisher Scientific). To measure transcript levels of neuroligin-4, we performed quantitative RT-PCR using the LightCycler480 Master Hydrolysis Probes Kit, RNase Inhibitor, and ROX Reference Dye (Roche Diagnostics). FAM-dye–coupled detection assays for mouse neuroligin-4 (20×) were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies: neuroligin-4 (forward, 5′-CCCAACGAAGATTGCCTCTAT-3′; reverse, 5′-CGTCATTATCCGCTAAGTCCTC-3′; and probe, 5′-TCCATCTTCCGTGGGCACATACAC-3′) and mouse actin (forward, 5′-ATGCCGGAGCCGTTGTC-3′; reverse, 5′-CCGCCACCAGTTCGCCATG-3′; and probe 5′-GCGAGCACAGCTTCTTTG-3′).

Electrophysiology

Transverse 200-µm-thick slices of the brainstem containing the MNTB were cut according to standard procedures with a vibratome (LeicA VT1200S) by using littermate KO and control mice at ages between P12 and 17 (Zhang et al., 2011, 2017). The extracellular recording solution contained (in mM) 125 NaCl, 25 NaHCO3, 2.5 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 25 glucose, 0.4 ascorbic acid, 3 myo-inositol, 2 Na-pyruvate, 2 CaCl2, and 1 MgCl2 (pH 7.4, when bubbled with 95% O2/5% CO2). For the recordings of fiber stimulation-evoked EPSCs, 50 µM picrotoxin and 1 µM strychnine were added to the extracellular solution. For recordings of mEPSCs in MNTB principal neurons, 1 µM TTX, 50 µM picrotoxin, 1 µM strychnine, and 50 µM APV were added. For recordings of mIPSCs in MNTB neurons, 1 µM TTX, 20 µM NBQX, and 50 µM APV were added, and 10 mM Ca 2+ was included with the extracellular recording solution to boost the frequency of mIPSC events. For EPSC recordings, internal solutions in the pipette included (in mM) 140 Cs-gluconate, 20 TEA, 10 Hepes, 5 Na2-phosphocreatine, 4 MgATP, 0.3 Na2GTP, and 5 Cs-EGTA, pH 7.2. For IPSC recordings, the internal solution in the pipette included (in mM) 140 CsCl, 10 Hepes, 5 Na2-phosphocreatine, 4 MgATP, 0.3 Na2GTP, 5 Cs-EGTA, pH 7.2. In quantifications of IPSCs evoked by minimal stimulation (>60% failure rate), only successful trials were included in the analysis. Whole-cell recordings in the voltage-clamp mode were made with an Axon amplifier, under visualization of neurons with an upright microscope (BX51WI; Olympus) equipped with a 40× water-immersion objective (Zeiss). Patch-pipettes had resistances of 2–3 MΩ, and series resistance (4–7 MΩ) was compensated at 75–85%. The residual R errors in postsynaptic recordings were comparable (∼1 MΩ) in all genotypes and were not corrected off-line. Cells were held at −60 mV in voltage-clamps; membrane potentials were not corrected for liquid junction potentials.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed on cryostat sections (30-µm thickness) of the mouse brain, which were processed on Superfrost Plus slides. Mice aged P12–P16 were transcardially perfused, and their brains were dissected and postfixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS overnight at room temperature. Permeabilization and blocking of the sections were done in PBS with 0.3% Triton X-100 (Sigma Aldrich) and 1% goat serum. We used the following primary antibodies: vGAT (1:500, 131011; Synaptic Systems), GlyR (1:500, 146011; Synaptic Systems), Syt2 (1:500, A320), vGluT1 (1:500; Millipore) incubated overnight at 4°C in blocking buffer. Secondary antibodies were from Invitrogen (Alexa Fluor 488, 555, and 647). Confocal images were acquired with an inverted Nikon IR+ microscope (Nikon) equipped with a 63× objective. Images were taken at 1,024 ×1,024 pixels with z-stack distance of 0.5 µm. Images were analyzed with software from Nikon IR+.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed by using the IgorPro software. Data are reported as mean ± SEM values, and statistical significance was evaluated by using unpaired, two-tailed student’s t test or single-factor ANOVA. Asterisks above brackets in data bar graphs indicate the level of statistical significance (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; and ***, P < 0.001). A bracket without symbol indicates P > 0.05 (not significant).

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 shows IPSCs and mIPSCs in neuroligin KO mice. Fig. S2 shows double labeling of vGAT and GlyR in MNTB principal neurons.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the members of the Südhof laboratory for invaluable discussions.

This study was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health, National Institutes of Health (R37 MH052804 to T.C. Südhof), a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship (DGE-114747 to W.D. Hale), the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (CNMPB FZT103 to N. Brose), the European Commission (EU-AIMS FP7-115300 to N. Brose), and the Max-Planck-Gesellschaft (to N. Brose).

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author contributions: B. Zhang and T.C. Südhof designed the research. B. Zhang performed the research. B. Zhang and T.C. Südhof analyzed data. B. Zhang, W.D. Hale, O. Gokce, and N. Brose contributed unpublished reagents and analytic tools. B. Zhang, N. Brose, and T.C. Südhof wrote the paper.

References

- Albrecht O., Dondzillo A., Mayer F., Thompson J.A., and Klug A.. 2014. Inhibitory projections from the ventral nucleus of the trapezoid body to the medial nucleus of the trapezoid body in the mouse. Front. Neural Circuits. 8:83 10.3389/fncir.2014.00083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association 2013. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. CBS Publishing, New Delhi, India. 991 pp. [Google Scholar]

- Awatramani G.B., Turecek R., and Trussell L.O.. 2004. Inhibitory control at a synaptic relay. J. Neurosci. 24:2643–2647. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5144-03.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awatramani G.B., Turecek R., and Trussell L.O.. 2005. Staggered development of GABAergic and glycinergic transmission in the MNTB. J. Neurophysiol. 93:819–828. 10.1152/jn.00798.2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey A., Le Couteur A., Gottesman I., Bolton P., Simonoff E., Yuzda E., and Rutter M.. 1995. Autism as a strongly genetic disorder: Evidence from a British twin study. Psychol. Med. 25:63–77. 10.1017/S0033291700028099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bekkers J.M., and Stevens C.F.. 1995. Quantal analysis of EPSCs recorded from small numbers of synapses in hippocampal cultures. J. Neurophysiol. 73:1145–1156. 10.1152/jn.1995.73.3.1145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolliger M.F., Frei K., Winterhalter K.H., and Gloor S.M.. 2001. Identification of a novel neuroligin in humans which binds to PSD-95 and has a widespread expression. Biochem. J. 356:581–588. 10.1042/bj3560581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolliger M.F., Pei J., Maxeiner S., Boucard A.A., Grishin N.V., and Südhof T.C.. 2008. Unusually rapid evolution of Neuroligin-4 in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 105:6421–6426. 10.1073/pnas.0801383105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borst J.G.G., and Soria van Hoeve J.. 2012. The calyx of Held synapse: From model synapse to auditory relay. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 74:199–224. 10.1146/annurev-physiol-020911-153236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brackmann M., Zhao C., Schmieden V., and Braunewell K.-H.. 2004. Cellular and subcellular localization of the inhibitory glycine receptor in hippocampal neurons. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 324:1137–1142. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.09.172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanda S., Aoto J., Lee S.-J., Wernig M., and Südhof T.C.. 2016. Pathogenic mechanism of an autism-associated neuroligin mutation involves altered AMPA-receptor trafficking. Mol. Psychiatry. 21:169–177. 10.1038/mp.2015.20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L.Y., Jiang M., Zhang B., Gokce O., and Südhof T.C.. 2017. Conditional deletion of all neurexins defines diversity of essential synaptic organizer functions for neurexins. Neuron. 94:611–625.e4. 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.04.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Daoud H., Bonnet-Brilhault F., Védrine S., Demattéi M.V., Vourc’h P., Bayou N., Andres C.R., Barthélémy C., Laumonnier F., and Briault S.. 2009. Autism and nonsyndromic mental retardation associated with a de novo mutation in the NLGN4X gene promoter causing an increased expression level. Biol. Psychiatry. 66:906–910. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delattre V., La Mendola D., Meystre J., Markram H., and Markram K.. 2013. Nlgn4 knockout induces network hypo-excitability in juvenile mouse somatosensory cortex in vitro. Sci. Rep. 3:2897 10.1038/srep02897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Kordi A., Winkler D., Hammerschmidt K., Kästner A., Krueger D., Ronnenberg A., Ritter C., Jatho J., Radyushkin K., Bourgeron T., et al. 2013. Development of an autism severity score for mice using Nlgn4 null mutants as a construct-valid model of heritable monogenic autism. Behav. Brain Res. 251:41–49. 10.1016/j.bbr.2012.11.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsabbagh M., Divan G., Koh Y.-J., Kim Y.S., Kauchali S., Marcín C., Montiel-Nava C., Patel V., Paula C.S., Wang C., et al. 2012. Global prevalence of autism and other pervasive developmental disorders. Autism Res. 5:160–179. 10.1002/aur.239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ey E., Yang M., Katz A.M., Woldeyohannes L., Silverman J.L., Leblond C.S., Faure P., Torquet N., Le Sourd A.M., Bourgeron T., and Crawley J.N.. 2012. Absence of deficits in social behaviors and ultrasonic vocalizations in later generations of mice lacking neuroligin4. Genes Brain Behav. 11:928–941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faber D.S., Young W.S., Legendre P., and Korn H.. 1992. Intrinsic quantal variability due to stochastic properties of receptor-transmitter interactions. Science. 258:1494–1498. 10.1126/science.1279813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein S., and Rutter M.. 1977. Infantile autism: A genetic study of 21 twin pairs. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 18:297–321. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1977.tb00443.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamann M., Billups B., and Forsythe I.D.. 2003. Non-calyceal excitatory inputs mediate low fidelity synaptic transmission in rat auditory brainstem slices. Eur. J. Neurosci. 18:2899–2902. 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2003.03017.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammer M., Krueger-Burg D., Tuffy L.P., Cooper B.H., Taschenberger H., Goswami S.P., Ehrenreich H., Jonas P., Varoqueaux F., Rhee J.S., and Brose N.. 2015. Perturbed hippocampal synaptic inhibition and γ-oscillations in a neuroligin-4 knockout mouse model of autism. Cell Reports. 13:516–523. 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.09.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heine M., Groc L., Frischknecht R., Béïque J.C., Lounis B., Rumbaugh G., Huganir R.L., Cognet L., and Choquet D.. 2008. Surface mobility of postsynaptic AMPARs tunes synaptic transmission. Science. 320:201–205. 10.1126/science.1152089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hippenmeyer S., Vrieseling E., Sigrist M., Portmann T., Laengle C., Ladle D.R., and Arber S.. 2005. A developmental switch in the response of DRG neurons to ETS transcription factor signaling. PLoS Biol. 3:e159 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffpauir B.K., Grimes J.L., Mathers P.H., and Spirou G.A.. 2006. Synaptogenesis of the calyx of Held: Rapid onset of function and one-to-one morphological innervation. J. Neurosci. 26:5511–5523. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5525-05.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoon M., Soykan T., Falkenburger B., Hammer M., Patrizi A., Schmidt K.-F., Sassoè-Pognetto M., Löwel S., Moser T., Taschenberger H., et al. 2011. Neuroligin-4 is localized to glycinergic postsynapses and regulates inhibition in the retina. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 108:3053–3058. 10.1073/pnas.1006946108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hruskova B., Trojanova J., Kulik A., Kralikova M., Pysanenko K., Bures Z., Syka J., Trussell L.O., and Turecek R.. 2012. Differential distribution of glycine receptor subtypes at the rat calyx of Held synapse. J. Neurosci. 32:17012–17024. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1547-12.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichtchenko K., Hata Y., Nguyen T., Ullrich B., Missler M., Moomaw C., and Südhof T.C.. 1995. Neuroligin 1: A splice site-specific ligand for beta-neurexins. Cell. 81:435–443. 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90396-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamain S., Quach H., Betancur C., Råstam M., Colineaux C., Gillberg I.C., Soderstrom H., Giros B., Leboyer M., Gillberg C., and Bourgeron T.. Paris Autism Research International Sibpair Study . 2003. Mutations of the X-linked genes encoding neuroligins NLGN3 and NLGN4 are associated with autism. Nat. Genet. 34:27–29. 10.1038/ng1136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamain S., Radyushkin K., Hammerschmidt K., Granon S., Boretius S., Varoqueaux F., Ramanantsoa N., Gallego J., Ronnenberg A., Winter D., et al. 2008. Reduced social interaction and ultrasonic communication in a mouse model of monogenic heritable autism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 105:1710–1715. 10.1073/pnas.0711555105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang M., Polepalli J., Chen L.Y., Zhang B., Südhof T.C., and Malenka R.C.. 2017. Conditional ablation of neuroligin-1 in CA1 pyramidal neurons blocks LTP by a cell-autonomous NMDA receptor-independent mechanism. Mol. Psychiatry. 22:375–383. 10.1038/mp.2016.80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ju A., Hammerschmidt K., Tantra M., Krueger D., Brose N., and Ehrenreich H.. 2014. Juvenile manifestation of ultrasound communication deficits in the neuroligin-4 null mutant mouse model of autism. Behav. Brain Res. 270:159–164. 10.1016/j.bbr.2014.05.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwabara N., DiCaprio R.A., and Zook J.M.. 1991. Afferents to the medial nucleus of the trapezoid body and their collateral projections. J. Comp. Neurol. 314:684–706. 10.1002/cne.903140405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landini M., Merelli I., Raggi M.E., Galluccio N., Ciceri F., Bonfanti A., Camposeo S., Massagli A., Villa L., Salvi E., et al. 2016. Association analysis of noncoding variants in neuroligins 3 and 4X genes with autism spectrum disorder in an Italian cohort. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 17:E1765 10.3390/ijms17101765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laumonnier F., Bonnet-Brilhault F., Gomot M., Blanc R., David A., Moizard M.-P., Raynaud M., Ronce N., Lemonnier E., Calvas P., et al. 2004. X-linked mental retardation and autism are associated with a mutation in the NLGN4 gene, a member of the neuroligin family. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 74:552–557. 10.1086/382137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson-Yuen A., Saldivar J.-S., Sommer S., and Picker J.. 2008. Familial deletion within NLGN4 associated with autism and Tourette syndrome. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 16:614–618. 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5202006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K., Kim Y., Lee S.-J., Qiang Y., Lee D., Lee H.W., Kim H., Je H.S., Südhof T.C., and Ko J.. 2013. MDGAs interact selectively with neuroligin-2 but not other neuroligins to regulate inhibitory synapse development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 110:336–341. 10.1073/pnas.1219987110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang J., Xu W., Hsu Y.-T., Yee A.X., Chen L., and Südhof T.C.. 2015. Conditional neuroligin-2 knockout in adult medial prefrontal cortex links chronic changes in synaptic inhibition to cognitive impairments. Mol. Psychiatry. 20:850–859. 10.1038/mp.2015.31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim R., Oleskevich S., Few A.P., Leao R.N., and Walmsley B.. 2003. Glycinergic mIPSCs in mouse and rat brainstem auditory nuclei: Modulation by ruthenium red and the role of calcium stores. J. Physiol. 546:691–699. 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.035071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakanishi M., Nomura J., Ji X., Tamada K., Arai T., Takahashi E., Bućan M., and Takumi T.. 2017. Functional significance of rare neuroligin 1 variants found in autism. PLoS Genet. 13:e1006940 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pak C., Danko T., Zhang Y., Aoto J., Anderson G., Maxeiner S., Yi F., Wernig M., and Südhof T.C.. 2015. Human neuropsychiatric disease modeling using conditional deletion reveals synaptic transmission defects caused by heterozygous mutations in NRXN1. Cell Stem Cell. 17:316–328. 10.1016/j.stem.2015.07.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pampanos A., Volaki K., Kanavakis E., Papandreou O., Youroukos S., Thomaidis L., Karkelis S., Tzetis M., and Kitsiou-Tzeli S.. 2009. A substitution involving the NLGN4 gene associated with autistic behavior in the Greek population. Genet. Test. Mol. Biomarkers. 13:611–615. 10.1089/gtmb.2009.0005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettem K.L., Yokomaku D., Takahashi H., Ge Y., and Craig A.M.. 2013. Interaction between autism-linked MDGAs and neuroligins suppresses inhibitory synapse development. J. Cell Biol. 200:321–336. 10.1083/jcb.201206028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilorge M., Fassier C., Le Corronc H., Potey A., Bai J., De Gois S., Delaby E., Assouline B., Guinchat V., Devillard F., et al. 2016. Genetic and functional analyses demonstrate a role for abnormal glycinergic signaling in autism. Mol. Psychiatry. 21:936–945. 10.1038/mp.2015.139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Südhof T.C. 2017. Synaptic neurexin complexes: A molecular code for the logic of neural circuits. Cell. 171:745–769. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.10.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J., Pang Z.P., Qin D., Fahim A.T., Adachi R., and Südhof T.C.. 2007. A dual-Ca2+-sensor model for neurotransmitter release in a central synapse. Nature. 450:676–682. 10.1038/nature06308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talebizadeh Z., Lam D.Y., Theodoro M.F., Bittel D.C., Lushington G.H., and Butler M.G.. 2006. Novel splice isoforms for NLGN3 and NLGN4 with possible implications in autism. J. Med. Genet. 43:e21 10.1136/jmg.2005.036897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trojanova J., Kulik A., Janacek J., Kralikova M., Syka J., and Turecek R.. 2014. Distribution of glycine receptors on the surface of the mature calyx of Held nerve terminal. Front. Neural Circuits. 8:120 10.3389/fncir.2014.00120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unichenko P., Yang J.-W., Kirischuk S., Kolbaev S., Kilb W., Hammer M., Krueger-Burg D., Brose N., and Luhmann H.J.. 2017. Autism related neuroligin-4 knockout impairs intracortical processing but not sensory inputs in mouse barrel cortex. Cereb. Cortex. •••:1–14. 10.1093/cercor/bhx165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Gersdorff H., and Borst J.G.G.. 2002. Short-term plasticity at the calyx of Held. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 3:53–64. 10.1038/nrn705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X., Xiong Z., Zhang L., Liu Y., Lu L., Peng Y., Guo H., Zhao J., Xia K., and Hu Z.. 2014. Variations analysis of NLGN3 and NLGN4X gene in Chinese autism patients. Mol. Biol. Rep. 41:4133–4140. 10.1007/s11033-014-3284-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan J., Oliveira G., Coutinho A., Yang C., Feng J., Katz C., Sram J., Bockholt A., Jones I.R., Craddock N., et al. 2005. Analysis of the neuroligin 3 and 4 genes in autism and other neuropsychiatric patients. Mol. Psychiatry. 10:329–332. 10.1038/sj.mp.4001629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu W.M., and Goodrich L.V.. 2014. Morphological and physiological development of auditory synapses. Hear. Res. 311:3–16. 10.1016/j.heares.2014.01.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B., and Südhof T.C.. 2016. Neuroligins are selectively essential for NMDAR signaling in cerebellar stellate interneurons. J. Neurosci. 36:9070–9083. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1356-16.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B., Sun L., Yang Y.-M., Huang H.-P., Zhu F.-P., Wang L., Zhang X.-Y., Guo S., Zuo P.-L., Zhang C.X., et al. 2011. Action potential bursts enhance transmitter release at a giant central synapse. J. Physiol. 589:2213–2227. 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.200154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B., Chen L.Y., Liu X., Maxeiner S., Lee S.-J., Gokce O., and Südhof T.C.. 2015. Neuroligins sculpt cerebellar Purkinje-cell circuits by differential control of distinct classes of synapses. Neuron. 87:781–796. 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.07.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B., Seigneur E., Wei P., Gokce O., Morgan J., and Südhof T.C.. 2017. Developmental plasticity shapes synaptic phenotypes of autism-associated neuroligin-3 mutations in the calyx of Held. Mol. Psychiatry. 22:1483–1491. 10.1038/mp.2016.157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C., Milunsky J.M., Newton S., Ko J., Zhao G., Maher T.A., Tager-Flusberg H., Bolliger M.F., Carter A.S., Boucard A.A., et al. 2009. A neuroligin-4 missense mutation associated with autism impairs neuroligin-4 folding and endoplasmic reticulum export. J. Neurosci. 29:10843–10854. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1248-09.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.