Abstract

The level of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) increases in some disorders such as vascular dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, and multiple sclerosis. We previously reported that in Alzheimer’s disease patients, a high level of GM-CSF in the brain parenchyma downregulated expression of ZO-1, a blood–brain barrier tight junction protein, and facilitated the infiltration of peripheral monocytes across the blood–brain barrier. However, the molecular mechanism underlying regulation of ZO-1 expression by GM-CSF is unclear. Herein, we found that the erythroblast transformation-specific (ETS) transcription factor ERG cooperated with the proto-oncogene protein c-MYC in regulation of ZO-1 transcription in brain microvascular endothelial cells (BMECs). The ERG expression was suppressed by miR-96 which was increased by GM-CSF through the phosphoinositide-3 kinase (PI3K)/Akt pathway. Inhibition of miR-96 prevented ZO-1 down-regulation induced by GM-CSF both in vitro and in vivo. Our results revealed the mechanism of ZO-1 expression reduced by GM-CSF, and provided a potential target, miR-96, which could block ZO-1 down-regulation caused by GM-CSF in BMECs.

Keywords: Brain microvascular endothelial cells, GM-CSF, miR-96, ERG, c-MYC, ZO-1

Introduction

The blood–brain barrier (BBB) separates the central nervous system (CNS) from the circulating blood, and forms a specific “milieu” for neurons by controlling the transport of substances including chemicals,1,2 nutrients,3,4 cells in the peripheral circulation,5–9 polypeptides, and others.10,11 The function of BBB mainly depends on brain microvascular endothelial cells (BMECs), which are characterized by complex tight junctions, reduced transcytosis, and some characteristic cell membrane transporters.12 The disassembly of tight junctions induces changes in material transportation, abnormal angiogenesis, inflammatory responses, and brain hypoperfusion, which could be the causes or consequences of certain diseases like Alzheimer’s disease,13,14 amyotrophic lateral sclerosis,15 and multiple sclerosis.16,17

Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) is produced in diverse CNS cells under pathological conditions,18–20 and it can cross the BBB.21 In view of the widespread expression of the GM-CSF receptor in the cerebral parenchyma, including the microglia, ependymal cells, choroid plexus cells, neurons, and endothelial cells,18,22–25 it is necessary to focus on the multiple functions of GM-CSF in physiological and/or pathological conditions. Interestingly, GM-CSF promotes the migration of human monocytes across the BBB into the brain parenchyma,9,19 which partially results from increasing of BBB permeability caused by reducing levels of zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1) and claudin-5 in brain microvascular endothelial cells (BMECs).9

ZO-1 is a cytoplasmic accessory protein with multiple domains that is involved in tight junction formation.26 ZO-1 and other family members link the transmembrane proteins including claudins, occludins, and junction adhesion molecules (JAMs) to other cytoplasmic proteins and actin microfilaments.27 Some studies reported the influence factors of ZO-1 expression, and partly revealed mechanisms of ZO-1 transcription. TNF-α and interleukin (IL)-6 decreased ZO-1 expression in HBMECs,28 and endophilin-1 over-expression reduced the expression of ZO-1.29 Recently, Chen et al.30 reported that JunD was a biological suppressor of ZO-1 expression in intestinal epithelial cells and ZO-1 played a critical role in maintaining epithelial barrier function. However, the molecular mechanisms regulating ZO-1 expression under physiological and/or pathological conditions are not fully understood. In this study, we explored the mechanism of ZO-1 transcription suppressed by GM-CSF in BMECs in vitro and in vivo.

Materials and methods

Animals

C57BL mice (male, 8–12 weeks old) used in this study were obtained from the Lab Animal Center of China Medical University. Recombinant mouse GM-CSF (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) was reconstituted at 100 µg/mL in sterile PBS containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin. miR-96 antagomir-cy3 and negative control antagomir (GenePharm, Shanghai, China) were dissolved in RNase-free H2O.

All mice were fed in a controlled environment (50% humidity, 22–25℃). The administration methods were described previously.9 Twenty-four male mice were divided into two groups: control group and experimental group. The control group mice received intracerebroventricular injections of PBS, and the experimental group mice were injected with 30 ng of recombinant mouse GM-CSF respectively.

In the rescue experiment, 36 male mice were randomly divided into three groups: control group, experimental group, and treatment group. The control group mice received PBS, the experimental group mice received respectively 30 ng of recombinant mouse GM-CSF and 400 µg of negative control antagomir, and the treatment group mice were given respectively 30 ng of recombinant mouse GM-CSF and 400 µg of miR-96 antagomir-cy3. After 48 h, mice from all groups were re-anesthetized, and brains were excised for immunohistofluorescence staining and Western blot analysis.

Efforts were made to minimize animal suffering and the number of animals used. Experimental procedures were conducted in accordance with the regulations of the animal protection laws of China and approved by the animal ethics committee of China Medical University (JYT-20060948). All protocols were reviewed and approved by the China Medical University Review Committee. All studies involving animals were performed in accordance with the ARRIVE (Animal Research: Reporting In Vivo Experiments) guidelines.

Immunohistofluorescence staining

Mice were anesthetized with pentobarbital (40 mg/kg) and perfused with 30 mL of PBS and 30 mL of 4% paraformaldehyde from the left ventricle in sequence. The brains were excised and stored in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight. On the second day, 50 µm vibratome slices were washed, blocked for 1 h in 8% (v/v) donkey serum dissolved in 0.01 M PB containing 0.5% Triton-X100 and incubated at 4℃ overnight with anti-CD31 (BD Biosciences), anti-ZO-1-FITC (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA USA), or lectin (Vector Labs, California, USA) diluted 1:100 in 0.01 M PB containing 0.1% Triton-X100 (Sigma-Aldrich, Darmstadt, Germany) and 1% (v/v) donkey serum (Sigma-Aldrich). After washing, all sections were incubated at room temperature for 3 h with Cy3-conjugated IgG goat anti-rabbit (Jackson ImmunoResearch, Hamburg, Germany) diluted 1:250 in 0.01 M PB containing 0.3% triton-X100. Nuclei were stained with 300 nM 4,6-diamidino-2-phenyl-indole (DAPI) for 20 min. Sections were covered with mounting medium (Vector Labs) and viewed via confocal microscopy (ZEN 2.1, Carl Zeiss, Germany).

The merged fluorescent mouse brain images were opened by ZEN 2.1(Carl Zeiss Microscopy GmbH) and amplified. We chose three typical capillaries per image, separated different channels and automatically generated pixel intensity for each channel. The ratio of ZO-1 (green) to CD31(red) pixel intensity was calculated, and the average ratio of each image was used for statistical analysis.

Cell culture

The human brain microvascular endothelial cells (HBMECs) were obtained from surgical resections in 4- to 7-year-old children31 and cultured in complete RPMI-1640 medium containing 10% foetal bovine serum (FBS), 10% Nu-serum (BD Biosciences), 2 mM glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 1× nonessential amino acids and 1× MEM vitamins.

Plasmid construction and luciferase assays

To construct the pGL3 plasmid (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) fused with different parts of the ZO-1 promoter between KpnI and XhoI, the following primers were designed: forward primers, 5′-CGGGGTACCGTGACAAATAAGTTAAAGTGAAAAATG-3′ (−2747) and 5′-CGGGGTACCGCACATCTTCTTAAATGGTAA-3′ (−2667); reverse primer, 5′-CGGCTCGAGCTTGTCTCTCTCCAGCG-3′; forward primer, 5′-CGGGGTACCGCAACTTGTAAAAGTGACAAATAAG-3′; reverse primers, 5′-CGGCTCGAGCTCCGCGGCGCTGGCCCG-3′ (−2787–−44), 5′-CGGCTCGAGCATCTCCCGAGAGCGAGC-3′ (−2787–−90), and 5′-CGGCTCGAGACAAAAGTCCGGGAAGC-3′ (−2787–−166). Different pGL3-ZO-1 truncations and the Renilla luciferase control reporter vector (Promega) were transfected into HBMECs using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). After 48 h, cells were lysed, and the luciferase activity was detected using SpectroMax M5 (MD, Sunnyvale, USA).

RNA interference

All siRNA sequences used in the study were designed and synthesized by Shanghai GenePharma Co., Ltd. siRNA sequences are listed in Supplementary Table 1. HBMECs (5.0 × 105) were transfected with 60 p mol Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) and 80 pmol siRNAs as mentioned previously. After 48 h, cells were lysed for the subsequent experiments. All siRNA sequences are listed in Table S1.

Cell immunofluorescence staining

Cells on the slides were washed three times with 1× PBS, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min and permeabilized with 0.05% Triton-X100 for 1 min. Then, 5% normal donkey serum in 1× PBS was used to block nonspecific binding for 1 h at 20–30℃, and cells were incubated at 4℃ overnight with anti-ZO-1-FITC (Thermo Scientific) diluted 1:100 in 1× PBS containing 1% (v/v) donkey serum. Finally, cells were stained with DAPI, diluted 1:2000 for 2 min and observed using a fluorescent microscope.

Real-time quantitative RT-PCR analysis

Total RNA was extracted using Trizol (Invitrogen) in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol. The cDNA was synthesized in a reaction system containing RNase-free DNase I (Takara Biotechnology (Dalian) Co. Ltd, Dalian, China), M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Promega), random primers (TaKaRa), RNase inhibitor (TaKaRa), dNTPs (TaKaRa) and ddH2O. The reverse transcription conditions were as follows: 37℃ for 1 h followed by 95℃ for 5 min. Real-time PCR was performed using an ABI 7500 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) with SYBR® Selected Master Mix (ABI) in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol, and the reaction conditions were as follows: 94℃ for 2 min followed by 40 cycles of 94℃ for 15 s and 60℃ for 40 s. All primers used are listed in Table S2.

Western blot analysis

Cells or mouse brain corpus striatum were lysed in PIPA buffer (Beyotime, Nantong, China) containing 1/25 cocktail (Roche, Germany) for 30 min, and the lysates were centrifuged (13,000 × g) at 4℃ for 15 min. A BCA protein assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA) was used to quantify protein concentrations. Different proteins were separated via 9% SDS-PAGE and transferred to a PVDF membrane electrophoretically. Then, the membranes were blocked in 5% non-fat milk in TBS containing 0.1% Tween-20 for 1 h and incubated overnight with primary antibodies as follows: ZO-1 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), ERG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), c-MYC (Abcam) and GAPDH (KangChen Biotech, Shanghai, China). All membranes were washed three times in PBST and incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at 20–30℃ for 1 h. The blots were incubated with SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Pierce), and observed via a LAS-3000 imaging system (Fujifilm). The relative signal densities were analyzed using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA), and GAPDH density was used as the internal control.

ChIP and re-ChIP

Cells (1.0 × 107) were prepared for ChIP assays, which were performed using a ChIP kit (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) in strict accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol. In brief, 1% formaldehyde was added to the medium for 10 min at 37℃ to form cross-linked protein-DNA complexes. Following sonication, immunoprecipitation of cross-linked protein/DNA, elution of protein/DNA complexes, reversal of cross-links of protein/ND complexes to free DNA, DNA purification using spin columns and real-time quantitative PCR was performed to determine whether the ERG binding site in the ZO-1 promoter was bound.

Re-ChIP experiments were performed as Harris32 described. The protein/DNA complexes from the initial immunoprecipitation (anti-ERG) were eluted for 30 min at 37℃ with 10 mM DTT. After centrifugation, the supernatant was removed and diluted 20 times in re-ChIP buffer. The second antibody (anti-c-MYC) was added, followed by cross-link reversal and DNA purification as mentioned previously. Finally, DNA products were amplified by real-time PCR. Primers are listed in Table S3.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 5.0 software (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). Statistical significance between two groups was assessed using a two-tailed Student’s t-test (α = 0.05). One-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s or Newman–Keuls’ test was performed for multiple comparisons. Differences were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

Results

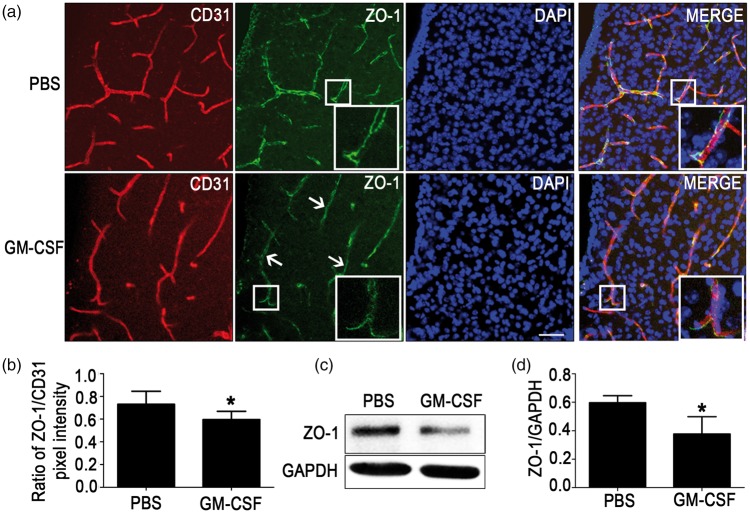

GM-CSF reduces ZO-1 expression in mouse brain microvessels

To investigate effect of GM-CSF on ZO-1 expression in brain microvascular endothelial cells in vivo, wild-type C57BL mice (male, 8–12 weeks old) were subjected to intracerebroventricular injections of mouse recombinant GM-CSF or an equal volume of PBS as previously mentioned.9 After 48 h, brains were separated for vibratome sectioning, and corpus striatums were lysed for Western blot. Immunohistofluorescence staining of corpus striatums (Figure 1(a) and (b)) revealed that the expression of ZO-1 (green) reduced significantly in the GM-CSF group than in the PBS group. Similarly, Western blot (Figure 1(c) and (d)) illustrated that ZO-1 expression in the GM-CSF group was also decreased significantly compared with that in the PBS group. The results indicated that intracerebral GM-CSF could decrease ZO-1 expression in vivo.

Figure 1.

Reduction of zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1) expression caused by granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) in mouse brain microvessels. (a) Immunohistofluorescence staining of ZO-1 expression in vivo. Vibratome slices (50 µm thick) of the corpus striatums from the PBS and GM-CSF groups were stained with CD31 (red), ZO-1 (green) and 4,6-diamidino-2-phenyl-indole (DAPI) (blue). Scale bar = 100 µm. (b) Quantification of pixel intensity, n = 6. (c, d) Western blot analysis illustrating the effect of mouse recombinant GM-CSF on ZO-1 expression in corpus striatum microvessels. An equivalent volume of PBS was injected as a control. A two-tailed t-test (α = 0.05) was used to compare ZO-1 expression. Data are shown as the mean ± SD, n = 6. *p < 0.05 vs. the control.

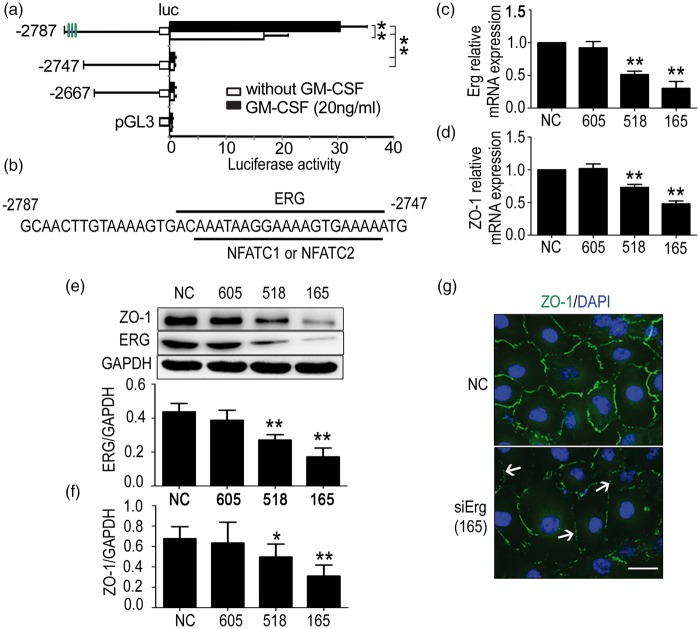

ETS transcription factor ERG regulates ZO-1 transcription in HBMECs

To further investigate the mechanism by which GM-CSF down-regulates ZO-1 expression in mouse brain microvessels, we cloned different parts of the ZO-1 promoter sequence into the pGL3 basic vectors and transfected them with pRL-TK into HBMECs that were either incubated in the presence or absence of 20 ng/mL GM-CSF. After 48 h, the cells were lysed, and ZO-1 expression was detected using a luciferase reporter assay. We found that GM-CSF reduced ZO-1 transcription via truncation at −2787 to −2747 (Figure 2(a)). The possible transcription factors were predicted using the Matinspector programme, and three transcription factors, namely ERG, NFATC1, and NFATC2, were screened according to the scores (Figure 2(b)). Then, the transcription factors were suppressed via RNA interference, results showed that siErg-518 and siErg-165 could significantly decrease the mRNA levels of Erg (Figure 2(c)) and ZO-1 (Figure 2(d)). The protein levels of Erg (Figure 2(e)) and ZO-1 (Figure 2(f)) were also reduced. Regarding Nfatc1, siNfatc1-2543, siNfatc1-2441, and siNfatc1-2070 reduced Nfatc1 mRNA expression (Supplementary Figure 1a). However, ZO-1 expression was neither decreased at the mRNA (Supplementary Figure 1b) nor at the protein level (Supplementary Figure 1c). Similarly, although siNfatc2-2036, siNfatc2-1949, and siNfatc2-1821 significantly suppressed the Nfatc2 mRNA expression (Supplementary Figure 1d), none of the siRNAs decreased the ZO-1 mRNA (Supplementary Figure 1e) or protein levels (Supplementary Figure 1f). Immunofluorescent staining revealed that siErg-165 obviously repressed ZO-1 expression (Figure 2(g)). These data indicated that ZO-1 expression is mainly regulated by ERG binding to the ZO-1 promoter region of −2787 to −2747.

Figure 2.

The erythroblast transformation-specific (ETS) transcription factor ERG regulates zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1) transcription in human brain microvascular endothelial cells (HBMECs). (a) Results of dual luciferase reporter experiments. Different pGL3 vectors cloned with different truncations of the ZO-1 promoter were cotransfected with pRL-TK into HBMECs stimulated with or without GM-CSF. After 24 h, luciferase activity was detected. One-way ANOVA was used to compare luciferase activity. Data are shown as the mean ± SD, n = 3. **p < 0.01 vs. the luciferase activity of the − 2787 truncation. (b) Paradigm of possible transcription factors. ERG, NFATC1 and NFATC2 transcription factors, which bind to the −2787 to −2747 truncation, were predicted using the Matinspector online software. (c) Effect of ERG interference on ZO-1 expression. SiErg-518 and siErg-165 reduced ERG and (d) ZO-1 mRNA levels significantly. (e) SiErg-518 and siErg-165 decreased ERG and (f) ZO-1 protein levels significantly. One-way ANOVA was used for repeated measurements. Data are shown as the mean ± SD, n = 3.*p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 vs. NC. (g) Immunofluorescent staining of ZO-1 expression. HBMECs from the NC and siErg-165 groups were stained with ZO-1 (green) and 4,6-diamidino-2-phenyl-indole (DAPI) (blue), and the down-regulation and disassembly of ZO-1 (not continuous) were indicated by the white arrows. Scale bar = 20 µm.

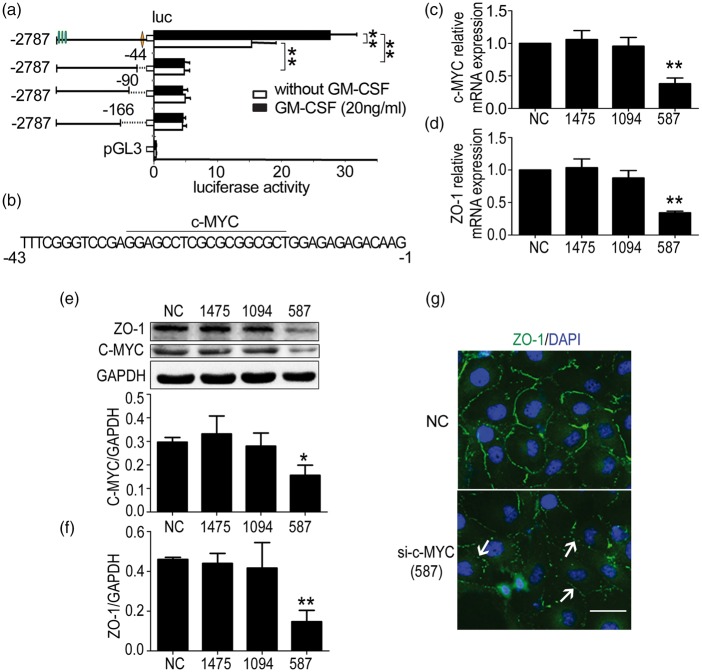

c-MYC regulates the transcription of ZO-1 in HBMECs

We have previously reported that the −675 to −1 truncation also participated in ZO-1 transcription.9 Therefore, we continued to clone different parts of this truncation into the pGL3 basic vectors and performed the luciferase reporter assay in the same manner. The results indicated that the −43 to −1 truncation included the transcription factor binding sites (Figure 3(a)). The possible transcription factors were also predicted using the Matinspector online software, with the highest score obtained for c-MYC (Figure 3(b)). Next, a c-MYC silencing assay demonstrated that sic-MYC-587 decreased c-MYC (Figure 3(c)) and ZO-1 mRNA levels (Figure 3(d)) significantly, and the protein expression of c-MYC (Figure 3(e)) and ZO-1 (Figure 3(f)) was also significantly depressed. Similarly, the inhibition of ZO-1 expression by c-MYC was observed via immunofluorescence (Figure 3(g)). These data demonstrated that ZO-1 expression is regulated by c-MYC binding to the ZO-1 promoter region of −43 to −1.

Figure 3.

c-MYC regulates the transcription of zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1), and c-MYC depletion reduces ZO-1 expression in human brain microvascular endothelial cells (HBMECs). (a) Results of dual luciferase reporter experiments. HBMECs were transfected with different pGL3 vectors containing different truncations of the ZO-1 promoter and pRL-TK, and luciferase activity was detected after 24 h. One-way ANOVA was used to compare the luciferase activity. Data are shown as the mean ± SD, n = 3. **p < 0.01 vs. the luciferase activity of the −2787 truncation. (b) Possible transcription factor binding to the −43 to −1 region. c-MYC binding to this region was predicted using the Matinspector online software. (c) Effect of c-MYC interference on ZO-1 expression. sic-MYC-587 reduced c-MYC and (d) ZO-1 mRNA levels significantly. (e) sic-MYC-587 decreased c-MYC and (f) ZO-1 protein levels significantly. One-way ANOVA was used for repeated measurements. Data are shown as the mean ± SD, n = 3. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 vs. NC. (g) Immunofluorescent staining of ZO-1 expression. HBMECs from the NC and c-MYC-587 groups were stained with ZO-1 (green) and 4,6-diamidino-2-phenyl-indole (DAPI) (blue), and the down-regulation and disassembly of ZO-1 (not continuous) were indicated by the white arrows. Scale bar = 20 µm.

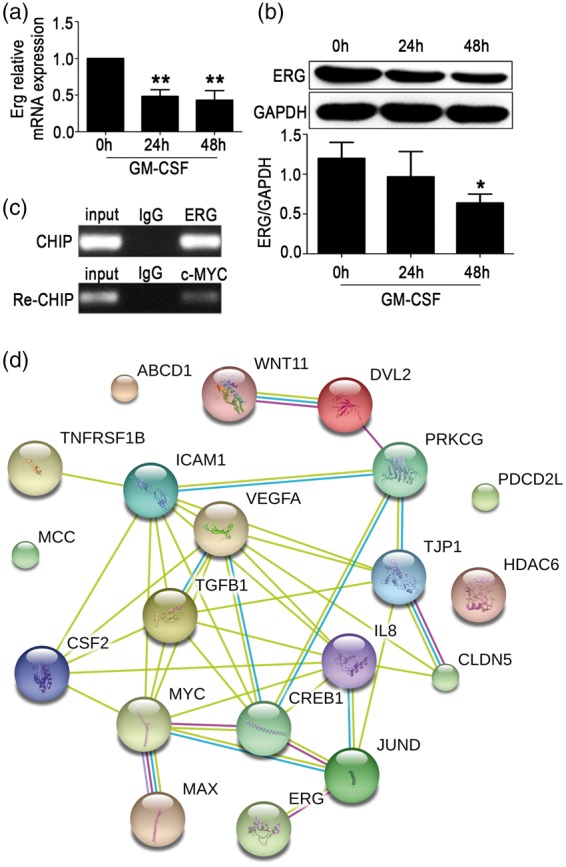

Expression of ERG is suppressed by GM-CSF, and ERG cooperates with c-MYC in the regulation of ZO-1 transcription

To investigate whether ERG and c-MYC expression were regulated by GM-CSF, we measured the expression of ERG and c-MYC in HBMECs stimulated by GM-CSF. The results illustrated that simulation with 20 ng/mL GM-CSF for 24 or 48 h significantly decreased ERG mRNA expression when compared with the untreated control (Figure 4(a)), and ERG protein was decreased significantly after 48 h of treatment (Figure 4(b)). However, GM-CSF treatment for 24 or 48 h did not affect the relative mRNA or protein expression of c-MYC (Supplementary Figure 2a and b). To further verify whether ERG cooperated with c-MYC in promoting ZO-1 transcription, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) and re-ChIP assays. The result demonstrated that ERG and c-MYC cooperated to bind to ZO-1 promoter and regulate ZO-1 transcription (Figure 4(c)). A limited network analysis by STRING (http://string-db.org/) illustrated that ERG and c-MYC might form a complex with CREB1, JUND, MAX and/or other factors to control ZO-1 transcription (Figure 4(d)). These data indicated that GM-CSF reduced ERG levels, which cooperated with c-MYC in regulating ZO-1 transcription in HBMECs.

Figure 4.

ETS transcription factor ERG expression was suppressed by granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), and ERG cooperates with c-MYC in regulating zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1) expression. Erg mRNA (a) and protein (b) levels in HBMECs were detected after stimulation with GM-CSF (20 ng/mL) for 24 or 48 h. One way ANOVA was used for repeated measurements. Data are shown as the mean ± SD, n = 3. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 vs. 0 h. (c) ERG and c-MYC cooperated to bind to the ZO-1 promoter sequence. In the ChIP assay, primary antibodies against IgG and ERG were used to immunoprecipitate the DNA sequences in the lysate of HBMECs, and specific primers were used to detect the ZO-1 promoter sequence. In the re-ChIP assay, IgG and c-MYC primary antibodies were used to immunoprecipitate the DNA sequences that were screened by the ERG primary antibody, and another pair of specific primers were used to detect the ZO-1 promoter sequence. (d) Paradigm of the predicted relationship among GM-CSF, ERG, and c-MYC. A limited network analysis was performed using STRING to clarify the factors that control ZO-1 transcription.

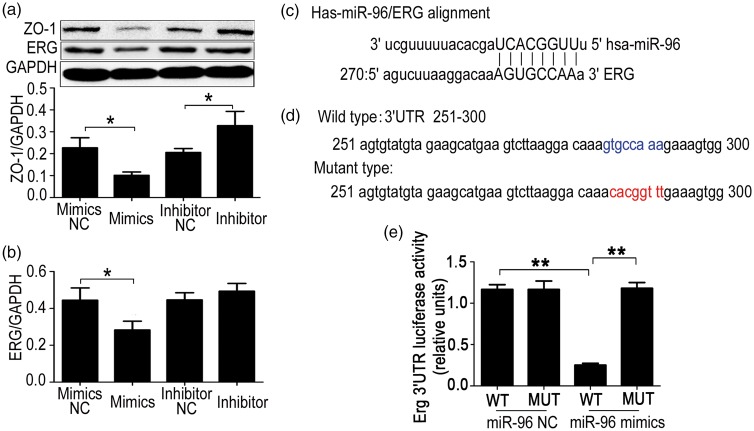

miR-96 targets ERG mRNA and regulates ERG expression

To investigate the mechanism by which GM-CSF reduces ERG expression, we predicted possible miRNAs targeting this transcription factor using the online software microRNA.org. Five miRNAs, namely miR-96, miR-33a, miR-30c, miR-30b, and miR-19b2, were screened. The result indicated that high levels of miR-96 could suppress ERG and ZO-1 expression (Figure 5(a) and (b)). However, miR-33a, miR-30c, miR-30b, and miR-19b2 did not suppress ERG expression (Supplementary Figure 3). Furthermore, inhibition of miR-96 could increase the ERG and ZO-1 expression (Figure 5(a) and (b)). The binding sites of miR-96 in the ERG 3′UTR were predicted by microRNA.org (Figure 5(c)). To further verify the targeted binding sites, we cloned wild-type or mutated sequences of the ERG 3′UTR into the pmirGLO vector (Figure 5(d)) and performed dual luciferase report experiments, which illustrated that miR-96 suppressed ERG expression by targeting the predicted binding site (Figure 5(e)).

Figure 5.

Effect of miR-96 on ETS transcription factor ERG expression. miR-96 targets ERG mRNA and regulates its expression. (a) Zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1) expression in HBMECs transfected with miR-96 mimics or inhibitors. Human brain microvascular endothelial cells (HBMECs) were transfected with miR-96 mimics or inhibitors, and ZO-1 and ERG protein levels (b) were detected by Western blot after 48 h. A two-tailed t-test (α = 0.05) was used for repeated measurements. Data are shown as the mean ± SD, n = 3. *p < 0.05 vs. NC. (c) The miR-96 binding site in the ERG 3′UTR was predicted using microRNA.org. (d) Wild-type and mutant sequences of the ERG 3′UTR (251–300). (e) Verification of the miR-96 binding to 3'UTR of ERG. The sequences of the wild-type and mutant ERG 3′UTR were cloned into pmirGLO vectors and transfected into HBMECs. A luciferase assay was performed to detect whether miR-96 targeted the ERG 3′'UTR. A 2-tailed t-test (α = 0.05) was used for repeated measurements. Data are shown as the mean ± SD, n = 3. **p < 0.01 vs. miR-96 mimics MUT or **p < 0.01 vs. miR-96 NC WT.

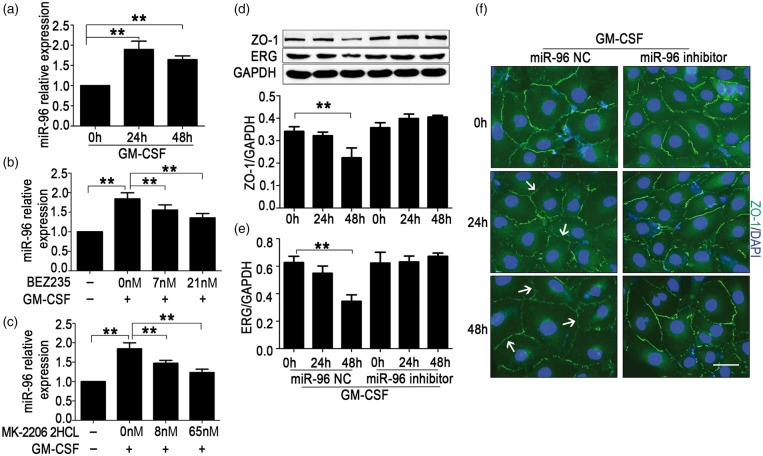

GM-CSF increases miR-96 levels through the PI3K/AKT pathway and miR-96 inhibition prevents ZO-1 suppression induced by GM-CSF in HBMECs

To further investigate whether miR-96 was regulated by GM-CSF, miR-96 levels were detected in HBMECs incubated with 20 ng/mL GM-CSF. Results showed that miR-96 levels were increased after 24 or 48 h of incubation (Figure 6(a)). Schabitz et al.22 reported that GM-CSF acted as a neuroprotective protein in the CNS through the PI3K-Akt pathway, and Qiu et al.33 discovered that the induction of cyclin D1 expression and cell cycle progression induced by GM-CSF were mediated partially by the PI3K/Akt pathway in endothelial progenitor cells. To study the pathway through which GM-CSF increased miR-96 levels, different concentrations of PI3K and AKT inhibitors were added to the medium of HBMECs, which were stimulated by GM-CSF simultaneously. We observed that various concentrations of the PI3K inhibitor BEZ235 and the AKT inhibitor MK-2206 2HCL respectively suppressed the up-regulation of miR-96 levels induced by GM-CSF in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 6(b) and (c)). miR-96 inhibition could block the down-regulation of ERG and ZO-1 induced by GM-CSF (Figure 6(d) and (e)), and also prevent the damage of ZO-1 assembly (Figure 6(f)). These results indicated that GM-CSF reduced ZO-1 expression via miR-96/ERG through the PI3K/AKT pathway.

Figure 6.

Granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) increases miR-96 levels through the PI3K/AKT pathway and miR-96 inhibition prevents the zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1) suppression induced by GM-CSF in human brain microvascular endothelial cells (HBMECs). (a) miR-96 expression in GM-CSF–stimulated HBMECs. HBMECs were incubated with 20 ng/mL GM-CSF, and miR-96 levels were detected after 24 or 48 h. One-way ANOVA was used for repeated measurements. Data are shown as the mean ± SD, n = 3. **p < 0.01 vs. 0 h. (b) Expression of miR-96 in HBMECs stimulated with GM-CSF and PI3K inhibitor or (C) AKT inhibitor. GM-CSF (20 ng/mL) and different concentrations of BEZ235 or MK-2206 2HCL were added. After 24 h, miR-96 levels were detected. One-way ANOVA was used for repeated measurements. Data are shown as the mean ± SD, n = 3. **p < 0.01 vs. 0 nM. (d) Protein levels of ZO-1 and (e) the erythroblast transformation-specific (ETS) transcription factor (ERG) in HBMECs treated with GM-CSF and the miR-96 NC or inhibitor. One-way ANOVA was used for repeated measurements. Data are shown as the means ± SD, n = 3. **p < 0.01 vs. 0 h + miR-96 NC. (f) Changes of ZO-1 expression observed by immunofluorescence. HBMECs were stained with ZO-1 (green) and 4,6-diamidino-2-phenyl-indole (DAPI) (blue), and the down-regulation and disassembly of ZO-1 (not continuous) were indicated by the white arrows. Scale bar = 20 µm.

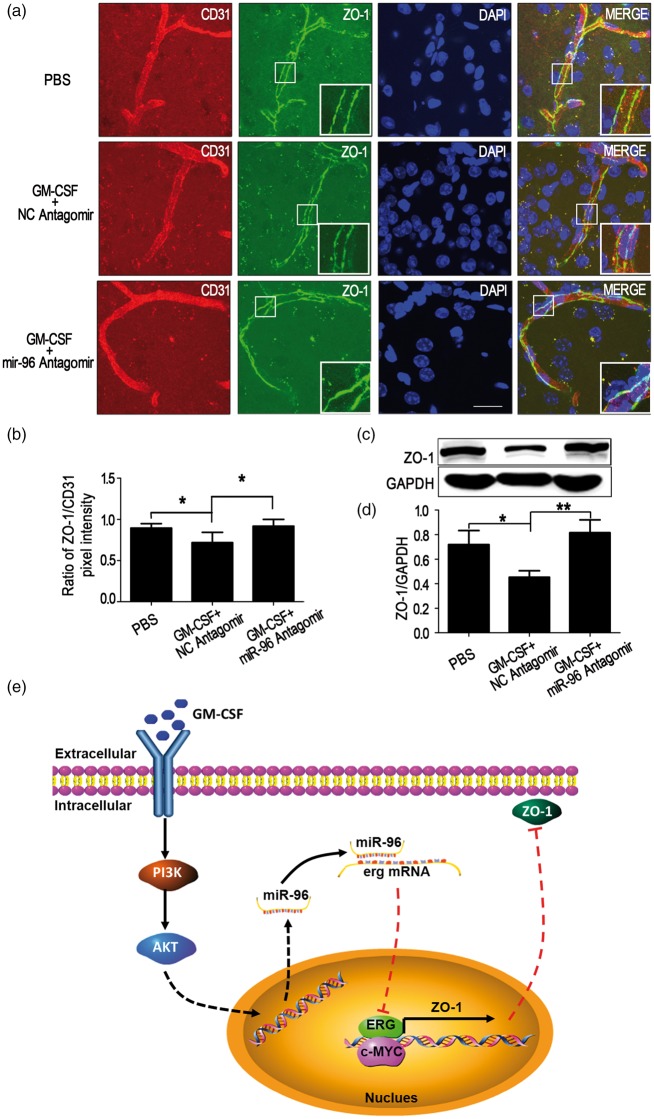

Inhibition of miR-96 prevents ZO-1 down-regulation induced by GM-CSF in mouse brain microvessels

To verify that miR-96 mediate ZO-1 down-regulation induced by GM-CSF in vivo, wild-type mice received intracerebroventricular injections of equal volumes of PBS, GM-CSF + NC antagomir or GM-CSF + miR-96 antagomir. After 48 h, brain corpus striatums were subjected to immunohistofluorescence staining and Western blot analysis. The results indicated that miR-96 antagomir-cy3 diffused into the brain corpus striatum and capillaries (Supplementary Figure 4). According to the ratio of green (ZO-1) to red (CD31) pixel intensity, miR-96 antagomir blocked ZO-1 down-regulation induced by GM-CSF in vivo (Figure 7(a) and (b)), and Western blot analysis also revealed that miR-96 antagomir prevented ZO-1 down-regulation caused by GM-CSF in brain corpus striatum capillaries (Figure 7(c) and (d)). The data indicated that GM-CSF suppressed ZO-1 expression through miR-96.

Figure 7.

miR-96 antagomir prevents zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1) down-regulation induced by granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) in mouse brain microvessels. (a) Rescue experiment of ZO-1 down-regulation as observed by immunohistofluorescence staining. Vibratome slices (50 µm thick) of corpus striatums from the PBS, GM-CSF + NC antagomir and GM-CSF + miR-96 antagomir groups were stained with CD31 (red), ZO-1 (green) and 4,6-diamidino-2-phenyl-indole (DAPI) (blue). Scale bar = 100 µm. (b) Quantification of pixel intensity, n = 6. (c, d) Western blot analysis detailing the effect of miR-96 antagomir on ZO-1 down-regulation caused by GM-CSF in mouse corpus striatum microvessels. One-way ANOVA was used to compare ZO-1 levels. Data are shown as the mean ± SD, n = 6. *p < 0.05 vs. the PBS group, **p < 0.01 vs. the GM-CSF + NC antagomir group. (e) Summary model of the down-regulation of ZO-1 induced by GM-CSF via miR-96/ERG in BMECs.

Discussion

GM-CSF, a type of pleiotropic cytokine, exerts its effects on most cell types in the haematopoietic compartment.34,35 It has been reported that GM-CSF levels are up-regulated in various neurological disorders, such as vascular dementia, Alzheimer’s disease and multiple sclerosis,36–39 although Tarkowski et al.40 reported that GM-CSF levels were undetectable in patients with Alzheimer’s disease or in the controls, which possibly resulted from the different genomic background, the number of study subjects or stages of disease. GM-CSF plays a variety of functions in CNS in multiple diseases including Alzheimer’s disease.9,18,19,36 Notably, GM-CSF promotes the migration of human monocytes across the BBB partly by suppressing ZO-1 transcription and augmenting claudin-5 degradation.9,19 However, the mechanism by which GM-CSF suppresses ZO-1 transcription in HBMECs is unclear. Clarification of this mechanism may provide potential targets for regulating human monocyte across the BBB in patients with Alzheimer’s disease.

ZO-1 is one of the critical tight junction proteins in keeping paracellular barrier of BBB. Some researchers have paid effort to the mechanisms of ZO-1 transcriptional regulation. Chen et al.30 discovered that JunD binding to the −2787 to −2227 region of the ZO-1 promoter suppressed ZO-1 transcription in intestinal epithelial cells, and this process was mediated through a CREB binding site in the −620 to −446 region. Shang et al.9 demonstrated that GM-CSF suppressed ZO-1 transcription through some factor binding to the −2787 to −1988 region of ZO-1 promoter, and factors binding to the −2787 to −1988 as well as −675 to −1 regions cooperate to promote ZO-1 transcription in HBMECs. It was necessary to identify the transcription factors that mediate suppression of ZO-1 expression by GM-CSF. In this study, dual luciferase report experiments and the Matinspector online software were employed, and we identified ERG and c-MYC (encoded by MYC) as ZO-1 transcription factors for the first time.

ERG, a member of the ETS transcription factor family, shares a highly conserved DNA binding domain that recognizes DNA with an conserved core motif of GGAA/T,41 and highly expresses in endothelial cells.42 ERG expression can be suppressed by pro-inflammatory cytokines,43 and it is a positive regulator of VE-cadherin, endoglin, von Willebrand factor, and claudin-5.41,44,45 In addition, ERG could negatively regulate levels of IL-8 and intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM)-1.43,46 Although it has been reported that ERG stimulated by inflammation promotes vascular stability and angiogenesis and maintains barrier function,41,44,47,48 we discovered that ERG functioned as a positive transcription factor of ZO-1, and GM-CSF could reduce ERG expression in HBMECs. We also found another transcription factor, c-MYC, which cooperated with ERG in promoting ZO-1 transcription. However, GM-CSF did not affect c-MYC expression according to our results. Similarly, both c-MYC mRNA and protein stability were not affected by GM-CSF in factor-dependent human leukemic cell lines (MO7e and F36P).49 c-MYC depletion suppressed CLDN5 and ICAM1 expression in the brain endothelium.50 In addition, c-MYC was associated with higher microvessel density in medulloblastoma.51 In this study, we observed that ERG cooperated with c-MYC to promote ZO-1 transcription in HBMECs for the first time.

Based on our results and published ZO-1 transcription factors,28,30,52 influence factors of GM-CSF levels,40 ERG,41,46–48,53 and c-MYC,49,50,54,55 STRING network analysis suggested that ERG and c-MYC may form a complex with CREB1, JUND, MAX and/or other factors to regulate ZO-1 transcription under different conditions, whereas GM-CSF suppressed ZO-1 transcription by reducing ERG levels.

We also discovered that miR-96, which was up-regulated by GM-CSF, suppressed ERG expression both in vitro and in vivo. Previous investigations of miR-96 were mostly focused on tumour or cancer fields, and its functions varied widely. For example, miR-96 promoted breast cancer tumour proliferation and invasion as well as oesophageal cancer proliferation and chemo- or radioresistance both by targeting RECK,56,57 suppressed renal cell carcinoma invasion via the downregulation of ezrin,58 accelerated the growth of prostate carcinoma cells by suppressing MTSS1,59 and facilitated proliferation and invasion through targeting ephrin A5 in hepatocellular carcinoma.60 Noticeably, miR-96 levels increased in young endothelial cells compared with that in senescent endothelial cells, which could result in differential expressions of downstream genes.61 In view of the crucial functions of ERG in endothelial cells,47 the discovery that miR-96 suppressed ERG expression was extremely meaningful. In particular, inhibition of miR-96 in vivo prevented the down-regulation of ZO-1 induced by GM-CSF, which could act as a potential tool for controlling monocytes across the BBB, although the role of monocytes in cerebral parenchyma needed to be further studied.

The GM-CSF signalling pathway has been revealed.62 GM-CSF most prominently induces PI3K-Akt signalling. Inhibition of Akt strongly decreased the neuroprotective function of GM-CSF,22 and GM-CSF induced cyclin D1 expression and the proliferation of endothelial progenitor cells via PI3K and MAPK signalling.33 In this study, we confirmed that inhibitors of PI3K or AKT blocked the up-regulation of miR-96 stimulated by GM-CSF.

In summary, GM-CSF up-regulated miR-96 expression through the PI3K/AKT pathway, which resulted in decreased ERG expression. Then, a lower level of ERG cooperated with c-MYC to promote ZO-1 transcription, and ZO-1 protein levels were reduced in tight junctions. This research revealed the transcriptional regulation of ZO-1 by GM-CSF in BMECs to some extent, partly confirmed the disadvantageous effects of GM-CSF on the BBB and provided a potential target, miR-96, which could prevent ZO-1 down-regulation caused by GM-CSF both in vitro and in vivo.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs. Monique Stins and Kwang Sik Kim (Department of Pediatrics, John Hopkins University School of Medicine) for providing HBMECs.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China [31171291, 31571057], Research Fund for the Doctoral Program of Higher Education of China [20132104110019], The Ministry of Education Innovation team project [2012CB722405], and Liaoning Provincial Department of Education Key Laboratory project [LZ2015074].

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Authors’ contributions

Contributions: DSS and YHC designed the experiments and analyzed data. HZ, SHZ, and JLZ performed the experiments. DSS and HZ wrote the manuscript. WDZ, WGF, DXL, and JYW provided technical supports.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material for this paper can be found at the journal website: http://journals.sagepub.com/home/jcb

References

- 1.Rosa, L, Galant, LS, Dall'Igna, et al. Cerebral oedema, blood-brain barrier breakdown and the decrease in Na( + ),K( + )-ATPase activity in the cerebral cortex and hippocampus are prevented by dexamethasone in an animal model of maple syrup urine disease. Mol Neurobiol 2016; 53: 3714–3723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen YJ, Wallace BK, Yuen N, et al. Blood-brain barrier KCa3.1 channels: Evidence for a role in brain Na uptake and edema in ischemic stroke. Stroke 2015; 46: 237–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hawkins RA, Mans AM, Hibbard LS, et al. Regional transport of some essential nutrients across the blood-brain barrier in normal and diseased states. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1988; 529: 40–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Winkler EA, Nishida Y, Sagare AP, et al. GLUT1 reductions exacerbate Alzheimer's disease vasculo-neuronal dysfunction and degeneration. Nat Neurosci 2015; 18: 521–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Debeb BG, Lacerda L, Anfossi S, et al. miR-141-mediated regulation of brain metastasis from breast cancer. J Natnl Cancer Inst 2016, pp. 108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li B, Zhao WD, Tan ZM, et al. Involvement of Rho/ROCK signalling in small cell lung cancer migration through human brain microvascular endothelial cells. FEBS Lett 2006; 580: 4252–4260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang K, Tian L, Liu L, et al. CXCL1 contributes to beta-amyloid-induced transendothelial migration of monocytes in Alzheimer's disease. PloS One 2013; 8: e72744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Man SM, Ma YR, Shang DS, et al. Peripheral T cells overexpress MIP-1alpha to enhance its transendothelial migration in Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging 2007; 28: 485–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shang DS, Yang YM, Zhang H, et al. Intracerebral GM-CSF contributes to transendothelial monocyte migration in APP/PS1 Alzheimer’s disease mice. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2016; 36: 1978–1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zlokovic BV. The blood-brain barrier in health and chronic neurodegenerative disorders. Neuron 2008; 57: 178–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao Z, Nelson AR, Betsholtz C, et al. Establishment and dysfunction of the blood-brain barrier. Cell 2015; 163: 1064–1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hawkins BT, Davis TP. The blood-brain barrier/neurovascular unit in health and disease. Pharmacol Rev 2005; 57: 173–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Erickson MA, Banks WA. Blood-brain barrier dysfunction as a cause and consequence of Alzheimer's disease. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2013; 33: 1500–1513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li JC, Han L, Wen YX, et al. Increased permeability of the blood-brain barrier and Alzheimer's disease-like alterations in slit-2 transgenic mice. J Alzheimer's Dis 2015; 43: 535–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qosa H, Lichter J, Sarlo M, et al. Astrocytes drive upregulation of the multidrug resistance transporter ABCB1 (P-Glycoprotein) in endothelial cells of the blood-brain barrier in mutant superoxide dismutase 1-linked amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Glia 2016; 64: 1298–1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shimizu F, Kanda T. Disruption of blood-brain barrier in multiple sclerosis and neuromyelitis optica. Nihon Rinsho 2014; 72: 1949–1954. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ortiz GG, Pacheco-Moises FP, Macias-Islas MA, et al. Role of the blood-brain barrier in multiple sclerosis. Arch Med Res 2014; 45: 687–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Volmar CH, Ait-Ghezala G, Frieling J. The granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) regulates amyloid beta (Abeta) production. Cytokine 2008; 42: 336–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vogel DY, Kooij G, Heijnen PD, et al. GM-CSF promotes migration of human monocytes across the blood brain barrier. Eur J Immunol 2015; 45: 1808–1819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spampinato SF, Obermeier B, Cotleur A, et al. Sphingosine 1 phosphate at the blood brain barrier: Can the modulation of S1P receptor 1 influence the response of endothelial cells and astrocytes to inflammatory stimuli? PloS One 2015; 10: e0133392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McLay RN, Kimura M, Banks WA, et al. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor crosses the blood–brain and blood–spinal cord barriers. Brain 1997; 120: 2083–2091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schabitz WR, Kruger C, Pitzer C, et al. A neuroprotective function for the hematopoietic protein granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF). J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2008; 28: 29–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parajuli B, Sonobe Y, Kawanokuchi J, et al. GM-CSF increases LPS-induced production of proinflammatory mediators via upregulation of TLR4 and CD14 in murine microglia. J Neuroinflammation 2012; 9: 268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ridwan S, Bauer H, Frauenknecht K, et al. Distribution of granulocyte-monocyte colony-stimulating factor and its receptor alpha-subunit in the adult human brain with specific reference to Alzheimer’s disease. J Neural Transm 2012; 119: 1389–1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Franzen R, Bouhy D, Schoenen J. Nervous system injury: Focus on the inflammatory cytokine ‘granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor’. Neurosci Lett 2004; 361: 76–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ueno M. Molecular anatomy of the brain endothelial barrier: An overview of the distributional features. Curr Med Chem 2007; 14: 1199–1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Forster C. Tight junctions and the modulation of barrier function in disease. Histochem Cell Biol 2008; 130: 55–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rochfort KD, Cummins PM. Cytokine-mediated dysregulation of zonula occludens-1 properties in human brain microvascular endothelium. Microvasc Res 2015; 100: 48–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu W, Wang P, Shang C, et al. Endophilin-1 regulates blood-brain barrier permeability by controlling ZO-1 and occludin expression via the EGFR-ERK1/2 pathway. Brain Res 2014; 1573: 17–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen J, Xiao L, Rao JN, et al. JunD represses transcription and translation of the tight junction protein zona occludens-1 modulating intestinal epithelial barrier function. Mol Biol Cell 2008; 19: 3701–3712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stins MF, Gilles F, Kim KS. Selective expression of adhesion molecules on human brain microvascular endothelial cells. J Neuroimmunol 1997; 76: 81–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harris DP, Chandrasekharan UM, Bandyopadhyay S, et al. PRMT5-mediated methylation of NF-κB p65 at Arg174 is required for endothelial CXCL11 gene induction in response to TNF-α and IFN-γ costimulation. PloS One 2016; 11: e0148905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Qiu C, Xie Q, Zhang D, et al. GM-CSF induces cyclin D1 expression and proliferation of endothelial progenitor cells via PI3K and MAPK signaling. Cell Physiol Biochem 2014; 33: 784–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Woodcock JM, McClure BJ, Stomski FC, et al. The human granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) receptor exists as a preformed receptor complex that can be activated by GM-CSF, interleukin-3, or interleukin-5. Blood 1997; 90: 3005–3017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hansen G, Hercus TR, McClure BJ, et al. The structure of the GM-CSF receptor complex reveals a distinct mode of cytokine receptor activation. Cell 2008; 134: 496–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tarkowski E, Wallin A, Regland B, et al. Local and systemic GM-CSF increase in Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia. Acta Neurol Scand 2001; 103: 166–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Patel NS, Paris D, Mathura V, et al. Inflammatory cytokine levels correlate with amyloid load in transgenic mouse models of Alzheimer's disease. J Neuroinflammation 2005; 2: 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mazzi V. Cytokines and chemokines in multiple sclerosis. Clin Ter 2015; 166: e62–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mellergard J, Edstrom M, Vrethem M, et al. Natalizumab treatment in multiple sclerosis: Marked decline of chemokines and cytokines in cerebrospinal fluid. Mult Scler 2010; 16: 208–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tarkowski E, Andreasen N, Tarkowski A. Intrathecal inflammation precedes development of Alzheimer's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2003; 74: 1200–1205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wasylyk B, Hagman J, Gutierrez-Hartmann A. Ets transcription factors: nuclear effectors of the Ras-MAP-kinase signaling pathway. Trends Biochem Sci 1998; 23: 213–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yuan L, Le Bras A, Sacharidou A, et al. ETS-related gene (ERG) controls endothelial cell permeability via transcriptional regulation of the claudin 5 (CLDN5) gene. J Biol Chem 2012; 287: 6582–6591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sperone A, Dryden NH, Birdsey GM, et al. The transcription factor Erg inhibits vascular inflammation by repressing NF-kappaB activation and proinflammatory gene expression in endothelial cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2011; 31: 142–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Birdsey GM, Dryden NH, Amsellem V, et al. Transcription factor Erg regulates angiogenesis and endothelial apoptosis through VE-cadherin. Blood 2008; 111: 3498–3506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Randi AM, Sperone A, Dryden NH, et al. Regulation of angiogenesis by ETS transcription factors. Biochem Soc Trans 2009; 37: 1248–1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yuan L, Nikolova-Krstevski V, Zhan Y, et al. Antiinflammatory effects of the ETS factor ERG in endothelial cells are mediated through transcriptional repression of the interleukin-8 gene. Circ Res 2009; 104: 1049–1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Birdsey GM, Shah AV, Dufton N, et al. The endothelial transcription factor ERG promotes vascular stability and growth through Wnt/beta-catenin signaling. Develop Cell 2015; 32: 82–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Birdsey GM, Dryden NH, Shah AV, et al. The transcription factor Erg regulates expression of histone deacetylase 6 and multiple pathways involved in endothelial cell migration and angiogenesis. Blood 2012; 119: 894–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kobayashi N, Saeki K, Yuo A. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor and interleukin-3 induce cell cycle progression through the synthesis of c-Myc protein by internal ribosome entry site-mediated translation via phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathway in human factor-dependent leukemic cells. Blood 2003; 102: 3186–3195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Musolino PL, Gong Y, Snyder JM, et al. Brain endothelial dysfunction in cerebral adrenoleukodystrophy. Brain 2015; 138: 3206–3220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stanic G, Cupic H, Zarkovic K, et al. C-myc expression in the microvessels of medulloblastoma. Coll Antropol 2011; 35: 39–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Weiler F, Marbe T, Scheppach W, et al. Influence of protein kinase C on transcription of the tight junction elements ZO-1 and occludin. J Cell Physiol 2005; 204: 83–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mochmann LH, Bock J, Ortiz-Tanchez J, et al. Genome-wide screen reveals WNT11, a non-canonical WNT gene, as a direct target of ETS transcription factor ERG. Oncogene 2011; 30: 2044–2056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wilson A, Murphy MJ, Oskarsson T, et al. c-Myc controls the balance between hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal and differentiation. Genes Develop 2004; 18: 2747–2763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dang CV, O'Donnell KA, Zeller KI, et al. The c-Myc target gene network. Semin Cancer Biol 2006; 16: 253–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang J, Kong X, Li J, et al. miR-96 promotes tumor proliferation and invasion by targeting RECK in breast cancer. Oncol Rep 2014; 31: 1357–1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Xia H, Chen S, Chen K, et al. MiR-96 promotes proliferation and chemo- or radioresistance by down-regulating RECK in esophageal cancer. Biomed Pharmacother 2014; 68: 951–958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yu N, Fu S, Liu Y, et al. miR-96 suppresses renal cell carcinoma invasion via downregulation of Ezrin expression. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2015; 34: 107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Xu L, Zhong J, Guo B, et al. miR-96 promotes the growth of prostate carcinoma cells by suppressing MTSS1. Tumour Biol 2016; 37: 12023–12032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang TH, Yeh CT, Ho JY, et al. OncomiR miR-96 and miR-182 promote cell proliferation and invasion through targeting ephrinA5 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol Carcinogen 2016; 55: 366–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang JB, Zhu XN, Cui J, et al. Differential expressions of microRNA between young and senescent endothelial cells. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi 2012; 92: 2205–2209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gomez-Cambronero J, Veatch C. Emerging paradigms in granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor signaling. Life Sci 1996; 59: 2099–2111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.