Abstract

The responsiveness to socioeconomic determinants is perceived as highly crucial in preventing the high mortality and morbidity rates of traditional male circumcision initiates in the Eastern Cape, a province in South Africa. The study sought to describe social determinants and explore economic determinants related to traditional circumcision of boys from 12 to 18 years of age in Libode rural communities in Eastern Cape Province. From the results of a descriptive cross-sectional survey (n = 1,036), 956 (92.2%) boys preferred traditional male circumcision because of associated social determinants which included the variables for the attainment of social manhood values and benefits; 403 (38.9%) wanted to attain community respect; 347 (33.5%) wanted the accepted traditional male circumcision for hygienic purposes. The findings from the exploratory focus group discussions were revolving around variables associated with poverty, unemployment, and illegal actions to gain money. The three negative economic determinants were yielded as themes: (a) commercialization and profitmaking, (b) poverty and unemployment, (c) taking health risk for cheaper practices, and the last theme was the (d) actions suggested to prevent the problem. The study concluded with discussion and recommendations based on a developed strategic circumcision health promotion program which is considerate of socioeconomic determinants.

Keywords: traditional male circumcision, consideration, socioeconomic, determinants, primary prevention, deaths, complications

Introduction

Traditional male circumcision practice has been captured into a profit-making business. The media and the previous studies reported that the owners of illegal schools often operate like a syndicate demanding payments after recruiting boys for circumcision without the knowledge and consent of their parents (Nkwashu & Sifile, 2015). Kepe (2010) confirmed that the main challenge facing the affected communities is that the traditional male circumcision has now been commercialized and some people are making money profit out of the practice. The illegal traditional surgeons and initiate guardians are demanding cash payment or a combination of cash and alcohol as remuneration for services they have not properly provided.

Each year in South Africa, thousands of youths enter circumcision initiation schools. Tragically, some of these traditional circumcision initiates often experience complications which subsequently require costly medical treatment (Anike, Govender, Ndimande, & Tumbo, 2013). The Eastern Cape Department of Health reported a total of 5,035 circumcision initiates admitted to hospitals, 453 deaths, and 214 penile amputations between June 2006 and June 2013 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Statistics of Hospital Admissions, Amputations, Deaths, and Arrests From June 2006 to June 2013 as Results of Traditional Circumcision in the Eastern Cape Province.

| Year | Hospital admissions | Amputations | Initiate deaths | Legal initiates | Illegal initiates | Arrests |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 June | 288 | 5 | 26 | 3,470 | 285 | 0 |

| 2006 December | 512 | 7 | 32 | 11,243 | 708 | 0 |

| 2007 June | 329 | 41 | 24 | 12,563 | 1,460 | 0 |

| 2007 December | 311 | 11 | 8 | 33,005 | 1,327 | 0 |

| 2008 June | 370 | 11 | 29 | 14,982 | 1,846 | 51 |

| 2008 December | 267 | 0 | 5 | 40,290 | 553 | 23 |

| 2009 June | 461 | 47 | 55 | 17,538 | 2,470 | 29 |

| 2009 December | 252 | 2 | 36 | 39,581 | 896 | 9 |

| 2010 June | 389 | 22 | 41 | 18,450 | 1,429 | 12 |

| 2010 December | 269 | 1 | 21 | 53,128 | 1,352 | 7 |

| 2011 June | 313 | 10 | 26 | 13,886 | 2,808 | 35 |

| 2011 December | 338 | 10 | 36 | 41,906 | 937 | 24 |

| 2012 June | 358 | 17 | 49 | 15,259 | 730 | 8 |

| 2012 December | 219 | 6 | 25 | 22,654 | 367 | 13 |

| 2013 June | 359 | 24 | 40 | 12,169 | 2,314 | 19 |

| Total | 5,035 | 214 | 453 | 349,785 | 19,547 | 230 |

Source. Eastern Cape Provincial Department of Health (2013).

The common deaths are mainly due to complications such as dehydration, septicemia, gangrene, pneumonia, assault, thromboembolism, and congestive heart failure (Meel, 2010; Venter, 2011). The hospitalization of the circumcision initiates imposes another challenge among AmaXhosa people because it is regarded as culturally unacceptable (Behrens, 2013). According to the traditional way, male circumcision is regarded as a highly valuable cultural ritual without the component of profit money making. Some view contact with conventional medical hospitals as a violation of the custom. Gudani (2011) stated that male circumcision initiation schools form part of cultural practices in South Africa and are therefore protected by the South African Constitution (Government of South Africa, 1996). The initiation schools are regarded as nonprofit cultural educational institutions where initiates are taught about societal norms, customs, and values. For example, among cultural groups where this practice is dominant, the circumcision initiation schools are set to educate initiates to be good and responsible leaders to their families and the community at large (World Health Organization [WHO], 2008).

All over the world, male circumcision has its roots deep in the structure of society. Far from being a simple technical act, even when performed in medical settings, it is a practice which carries with it a whole host of social meanings. Some of these meanings link to what it is to be a man, with circumcision taking place as a rite of passage into adulthood in several African and Oceanic societies (Aggleton, 2007). Among AmaXhosa people in the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa, circumcision is practiced as a male initiation rite, used as a transition from boyhood (ubukhwenkwe) to manhood (ubudoda; Mavundla, Netswera, Bottoman, & Toth, 2009). The AmaXhosa are one of the ethnic groups in Southern Africa that practice the ritual of circumcision. It should be noted that not all the AmaXhosa clans circumcise their adolescent boys. For example, the clans that are commonly known to practice the circumcision ritual in the Eastern Cape include the following: AbaThembu, AmaMfengu, AmaGcaleka, AmaRharhabe, AmaGqunukhwebe, AmaHlubi, AbeSuthu, and AmaBomvana (Nqeketo, 2008; WHO, 2008). Until recently, the practice was not seen among the AmaBhaca, AmaMpondo, AmaXesibe, or AmaNtlangwini, but the trend has changed, and the AmaMpondo in Pondoland are circumcising their adolescent boys. Historically other South African ethnic groups such as the AmaZulu, AbeTswana, and AmaShangaan have also ritually circumcised boys, but some of them have in recent years largely abandoned the practice (WHO, 2008).

It is claimed that some clans ceased to circumcise their boys during King Shaka Zulu wars. In the 1820s, in some parts of Pondoland, Eastern Cape Province traditional male circumcision, was partially abandoned among AmaMpondo because of ongoing attacks by the King Shaka Zulu warriors during times when circumcision initiations were in progress. The reemergence of male circumcision in the 1990s, when some of male adults were not circumcised, plunged this cultural practice into deep trouble due to a lack of direct adult supervision (Maluleke, 2015). Currently, in response to the call for the implementation of medical male circumcision (MMC), the National Department of Health (NDoH) in South Africa has developed the strategic plan for the scale-up of MMC from 2012 to 2016 and has set up a target of 4.3 million circumcisions by the end of 2016 for all young men from all ethnic groups to be circumcised. The plan reflects a multisectoral approach, which supports the vision of the NDoH to work in partnership with stakeholders to prevent HIV/AIDS and promote health (www.mmcinfo.co.za/partners).

The traditional male circumcision ritual is usually carried out twice a year, in June and December school holidays to make a provision for convenient periods of time for the school going boys. The initiates stay in the initiation school for about 3 to 4 weeks and observe all the cultural rites, including learning about sexual, individual, and community values (Nwanze & Mash, 2012). According to WHO (2008), the ritual of male circumcision is among the most secretive and sacred of rites among AmaXhosa society. These rites play a social role, mediating intergroup relations, renewing unity and integrating the sociocultural system. This cultural practice falls under the legal jurisdiction of the traditional leadership in the rural areas.

According to Kepe (2010), there are three important elderly men who are involved in the key aspects of male circumcision initiation (ukwaluka). They include the surgeon or the circumciser (ingcibi), the guardian or traditional nurse (ikhankatha), and the anointer (umthambisi).

Commercialization of Traditional Circumcision Practice

From its origin, money profitmaking was not part of the traditional circumcision initiation. It was common to offer portions of the meat slaughtered during initiation to the surgeon and the traditional nurse as a token of appreciation. This has changed over time and the whole thing has now been commercialized and some people are making huge profit out of the tradition. Even known and registered traditional surgeons, those who are called legal traditional surgeons are charging money from the parents of the initiates. In the early 2000s, the registered traditional surgeons and nurses were charging anything between R100 and R200 per initiate. Fees of R300 or more per service have been reported in some parts of the province, which is far expensive for parents whose children went for circumcision without their parents’ authorization (Kepe, 2010).

According to Bottoman, Mavundla, and Toth (2009), there are negative social determinants associated with traditional circumcision in the Eastern Cape. For example, the men who are circumcised in health facilities (MMC) are treated with contempt and disrespect among AmaXhosa people. They are not allowed to share certain community activities. For instance, those who did not complete the ritual according to tradition are not able to marry, start a family, partake in traditional activities such as sacrifices, or even become an ancestor after death. The House of Traditional Leaders is regarded as the custodian of traditional circumcision practice and it is very proud of the practice. In response to the high mortality and morbidity rates of traditional male circumcision initiates, the government officials passed an Act of Parliament to regulate this ancient practice. The Application of Health Standards in Traditional Circumcision Act (Act No. 6 of 2001) was promulgated with the aim of regulating the traditional male circumcision practice. The regulation requires that no person except a medical practitioner may perform any circumcision in the Eastern Cape Province without written permission of the medical officer designated for the area in which the circumcision is to be performed. Traditional surgeons who contravene this regulation are subject to arrest, however the rate of arrest is very low (Table 1).

The Spread of Commercialization With Criminal Components

In Gauteng Province, certain men were paid in cash and alcohol for bringing recruits to illegal schools. Owners of illegal schools often operated like a syndicate in establishing bogus (false) schools. In some incidences, the illegal surgeons would pretend to be organizing a soccer tournament for boys; outside their township, they forced them into a circumcision initiation school. The bogus surgeons would be paid as little as R30 per boy. The kingpin (principal) of bogus schools would make more money by sending a ransom letter to the parents of the boys. The parents are often threatened with fears that their children will not come back alive if they do not pay the money. These kingpins are reported to be wealthy people who organize drug abusers (nyaope addicts) to recruit boys for circumcision (Nkwashu & Sifile, 2015).

In Limpopo province, parents rescued their children from the initiation school and were forced to pay R1,550 to secure the release of their children. An initiation school in Ramotshinyadi near Modjadjiskloof had 158 initiates and it was shut down. The parents came to fetch their children and took them to hospital. The Limpopo House of Traditional Leaders warned the parents not to give money to illegal initiation schools. Some poor families cannot afford to pay the money charged by the registered traditional surgeons and nurses so their children become the victims of illegal practice (Nkwashu & Sfile, 2015). Coincidentally, the crisis of high mortality statistics of circumcision initiates has been occurring during the period of time when the country has been afflicted with poverty and unemployment. The ordinary South Africans are struggling to meet their basic household needs. In addition to the circumcision crisis, among the provinces in South Africa, Eastern Cape had the highest prevalence of food insecurity in 1999 (Labadarious et al., 2011). The unemployment rate was increased up to 31.8% in the Eastern Cape Province and 24.7% in South Africa in 2011 (Nyandeni Local Municipality, 2012-2013). The Deputy Minister of Traditional Affairs, Mr. Obed Bapela stated that they are working with other government departments to criminalize illegal initiation schools that are run by criminals who do not care about the welfare of the children but rather greedy for making money. There is a serious call for all stakeholders in South Africa to work together in preserving the cultural heritage from being hijacked by criminals (Sampear, 2015).

In the year 2014, the Minister of Health in the NDoH, Dr. Aaron Motsoaledi stated that the unnecessary deaths of numerous traditional circumcision initiates, as well as numerous injuries sustained in the Eastern Cape, Limpopo, and Mpumalanga provinces in recent years had warranted serious intervention of the government and traditional leaders. The minister also confirmed that his department fully supports safe male traditional initiation. He also added that the Department of Health in South Africa has the national budget for male circumcision of R385 million for 2014-2015 financial year and of this amount R180 million has been set aside for the support and preventive processes of the traditional circumcision initiation schools ( http://www.sanews.gov.za/south-africa/13-6-2014

According to Ncayiyana (2011), there are two central national arguments related to funding MMC in South Africa. First, that the scientific evidence is insufficient to justify that funding male circumcision will yield expected outcomes. There is a concern that utilizing such serious energy, money, and resources, particularly when circumcision programs have the potential of diverting money from other more effective interventions and second, that risk compensation (the potential increase in risky behavior after circumcision) may nullify any benefits of male circumcision. Hargreaves (2007) supported these arguments in confirming that in a WHO press conference that was held previously, it was acknowledged that there are a number of risks associated with scaling up male circumcision in some settings. There may be adverse effects of the surgery itself, particularly in resource-poor settings where hospital hygiene may be poor. Additionally, men who get circumcised may develop a false sense of protection and engage in high-risk behaviors that could reverse the partial protection provided by circumcision. The WHO/UNAIDS statement made it clear that circumcision needs to be part of a comprehensive prevention package, which includes the provision of HIV testing and counselling services (Hargreaves, 2007).

The study described and explored variables associated with socioeconomic determinants collectively as based on attainment of social respect and benefits, commercialization and profitmaking, taking health risk for cheaper illegal practices, and suggested socially acceptable actions to resolve the problem. Social determinants of health are the conditions in which people are born, grow up, live, work, and age with. These conditions influence a person’s opportunity to be healthy, his or her risk of illness, and life expectancy. In traditional male circumcision, relevant social determinants resulting in illnesses include poverty, unemployment, social exclusion, and poor shelter (WHO, 2008, 2012).

The Study Design

The study was designed to be a mixed-method research using both quantitative and qualitative approaches, utilizing sequential transformative strategy to allow for the convergence of multiple perspectives of the traditional male circumcision in Libode, Eastern Cape. A cross-sectional study was conducted to describe the perceptions of boys regarding the social determinants of traditional male circumcision. The focus group discussions (FGDs) explored the economic determinants related to traditional male circumcision. The study population included boys from 12 to 18 years who were attending school and living in the rural communities of Libode, Eastern Cape, during the period of 2010 to December 2013. The total population of Nyandeni was 290,390 in 2011 with the unemployment rate of 49.3%. Of the 290,390 people living in Nyandeni Local Municipality (research site) in 2011, 45.9% are African males and 53.5% African females (Nyandeni Local Municipality, 2012-2013).

Study Sampling

The study used both quantitative and qualitative research methods which included cross-sectional and FGDs, respectively.

Sampling for the Cross-Sectional Survey

Selection of villages for a cross-sectional survey was done utilizing a simple random method. Ten villages were selected from 129 rural communities. From the 10 villages, 22 schools were selected using simple random method to select 16 junior secondary schools and 6 senior secondary schools. However, some villages had two junior secondary school with no senior secondary schools.

According to the sample size, 50 boys per school was planned, but in the real setting, some populations were less than 50 and others were more. The reason behind that was that some boys went for other activities such as sport day, others rushing out for the contract transport back home. The school principals called all the boys to the assembly and boys were grouped in queues according to their ages from 12 to 18 years. The researcher used a simple random method to select the required number from the assembly.

Sampling for Focus Group Discussions

A total of three focus groups were selected using a purposive sampling method and there were 12 participants in each group (Egger, Spark, Lawson, & Donovan, 2005). A total of 36 circumcised boys participated in the three FDGs. The purposive sampling method was used to select boys for the FDGs based on the following criteria: young boys aged 12 to 18 years, must have lived in the village for not less than 6 months, must have interest in circumcision, must have interest in youth sexuality and HIV and AIDS issues, and must have voluntarily chosen to participate in the program.

Data Collection

The Questionnaire

A cross-sectional study was conducted and data collection was done using copies self-administered questionnaires. The questionnaire was developed in order to establish the description of social determinants related to traditional circumcision. It consisted of 57 closed-ended questions with Likert-type scale response options. The following aspects were tested with the closed-ended questions:

Personal demographic profile

Best age for circumcision

Traditional circumcision versus MMC

Acceptable circumcision practice in the communities

Type of circumcision practice preferred in the individual families

Best place for performing male circumcision, and

Benefits of traditional male circumcision

The copies of self-administered questionnaires were distributed and collected by the researcher and trained research assistants. The questionnaires were translated into IsiXhosa, home language which was the preferred language of all participants in the rural communities. All boys were able to read and write and research assistants were assisting those who did not understand filling of the questionnaire. A total of 1,036 questionnaires were distributed and collected by the research assistants the same day, within 30 to 45 minutes.

Focus Group Discussions

FGDs were used to explore the views and perceptions of only circumcised boys regarding economic determinants related to traditional circumcision. As circumcision is a sensitive subject among the AmaXhosa and traditional leaders, only boys were eligible to participate in the study. One FGD was conducted in each school and three schools were selected using simple random selection. Only circumcised young men were part of the three FGDs because the questions that were asked were only relevant to those who have already gone through the experienced of traditional male circumcision. The focus question was as follows: How much is paid to the traditional surgeons per circumcision client? The question was just a guide to allow the boys to discuss freely on the topic of economic determinants. Follow-up questions were asked to explore more information regarding the cost aspects related to traditional circumcision. For example, some questions were asked as follows: What are the costs and benefits of being circumcised in the community? Who buys food for the initiates in the initiation school? Small classrooms were arranged in each of the three schools and only the selected participants were involved in the discussion in closed doors. In-depth probing took place to gain quality information from the participants regarding economic determinants of related to traditional circumcision. Saturation of information was reached and there was no need to continue with the interviews. A digital voice recorder was used to record the collected data.

Ethics

The study proposal was submitted to the Research Committee of Walter Sisulu University for registration and approval. Ethical approval was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee of the University. Walter Sisulu University Senate Ethics Committee issued a certificate for the study to proceed. No individual names of the participants were used in this study. All participants signed the consent forms and those less than 18 years of age had written consent to participate in the study from their parents or guardians and the school principal. Permission to conduct the study was sought from the House of Traditional Leaders, Department of Education, community, and youth leaders.

Data Analysis

Analysis techniques for quantitative research included descriptive statistics which are presented in the form of tables and figures. The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 16.0 was used to analyze data with descriptive statistics utilizing frequencies and percentages. Qualitative data analysis involved the integration and synthesis of narrative and nonnumeric data that were reduced into themes and the Tesch’s eight-step data analysis method was used (Creswell, 2009). The process of analyzing data started during the collection stage to identify recurrent patterns. The collected data from the digital voice recordings was installed into the computer and translated from IsiXhosa into English and analyzed. As the interviews were conducted, records were maintained and they were reviewed constantly to discover additional questions that needed to be used or to offer descriptions of what was identified. This meant that the data were organized and prepared for analysis by first transcribing the interviews verbatim and then translating the parts that needed translation. The researchers subsequently read all the data to gain a general sense of the information and to begin to interpret their overall meaning. The information was coded and analyzed. In analysis of qualitative data, the researcher identified the most descriptive words for each topic and turned them into categories or subthemes. Topics that are related to each other were then grouped in order to reduce the number of categories and to create themes. The similar categories of data were grouped and analyzed using Tesch’s method. The limitation is that the study was conducted among AmaXhosa ethnic group in the Eastern Cape Province, but it is not only the AmaXhosa tribe that is affected with the problems related to traditional male circumcision in South Africa.

Trustworthiness of Findings

Both the findings from cross-sectional survey and FGDs were integrated to guarantee trustworthiness of the study (Babbie & Mouton, 2001). The researcher used data triangulation for the purpose of generating meaningful data and to ensure validity and reliability of the findings (Streubert & Carpenter, 2007). Guba’s model of trustworthiness was also used which also rests on credibility, transferability, confirmability, and dependability (Lincoln & Guba, 1985).

Results

The results from the cross-sectional survey are presented under the social variables: demographic profile of the participants, views of the participants regarding the social determinants related to traditional male circumcision and their views about the prevention of the negative impact of the determinants. The variables were described under the following social demographic characteristics and perceptions related to traditional circumcision: ages of participants, birth and residential places of participants, educational and circumcision status, perceptions about forms of circumcision, respect perceived as an important manhood value, perceived social benefits of traditional circumcision, and social reasons for choosing traditional circumcision.

Demographic Profile of Participants

The ages of participants in this study ranged from 12 to 18 years. The frequency and percentages differed in different ages. The peak age of the participants was 17 years with 207 (20%) boys. The majority of 990 (95.7%) participants were living in Libode rural communities; 449 (43.3%) had primary school education, 587 (56.7%) had secondary education; 363 (34.9%) were already circumcised and 673 (65.1%) were not yet circumcised (Table 2).

Table 2.

Demographic Characteristics Illustrating Social Variables.

| Social variables | Number of participants (n = 1,036) | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Age of participants | ||

| 12 | 61 | 5.9 |

| 13 | 113 | 10.9 |

| 14 | 142 | 13.7 |

| 15 | 161 | 15.5 |

| 16 | 203 | 19.8 |

| 17 | 207 | 20.0 |

| 18 | 149 | 14.4 |

| Birth place | ||

| Rural village | 807 | 77.9 |

| Township | 65 | 6.3 |

| City/suburb | 164 | 15.8 |

| Residential place | ||

| Rural village | 991 | 95.7 |

| Township | 39 | 3.8 |

| City/suburb | 6 | 0.6 |

| Educational level | ||

| Primary school | 449 | 43.3 |

| Secondary school | 587 | 56.7 |

| Circumcision status | ||

| Circumcised boys | 363 | 34.9 |

| Uncircumcised boys | 673 | 65.1 |

| What do you prefer? | ||

| Traditional circumcision | 956 | 92.3 |

| Hospital circumcision | 41 | 4.0 |

| I am not sure | 39 | 3.8 |

| What is the best place for circumcision? | ||

| Traditional circumcision | 677 | 65.3 |

| Hospital circumcision | 178 | 17.2 |

| I am not sure | 181 | 17.5 |

| Do you support hospital circumcision? | ||

| I definitely support it | 290 | 28.0 |

| I definitely do not support it | 505 | 48.7 |

| I am not sure | 241 | 23.3 |

Social Preference of Traditional Male Circumcision

The participants responded as follows: 956 (92.2%) preferred traditional circumcision, 41 (4%) preferred hospital circumcision (MMC); 677 (65.3%) indicated that the best place was a traditional setting, 178 (17.2%) indicated that it was a hospital setting (Table 2).

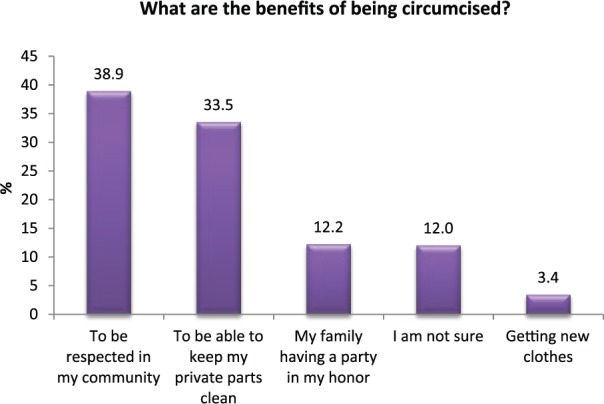

Social Benefits of Traditional Male Circumcision

Figure 1 illustrates in percentages the responses of and boys who from the question that enquire about benefits they perceived from being circumcised. A total of 403 (38.9%) responded that they want to be respected in the community; and 347 (33.5%) wanted to be able to keep their private parts clean.

Figure 1.

Social benefits of traditional male circumcision (n = 1,036).

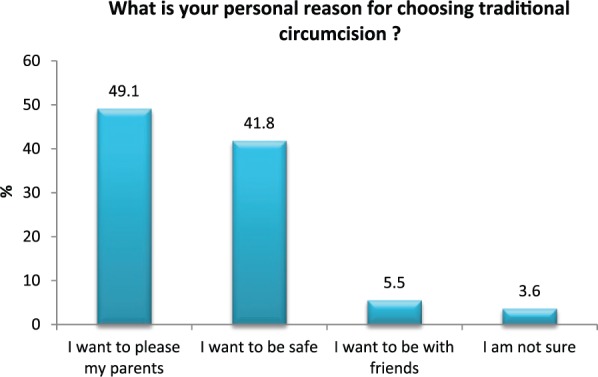

Personal Reasons for Choosing Traditional Male Circumcision

In Figure 2, 1,036 boys were asked a question about their personal reason for choosing traditional circumcision. Among them, 49.1% responded that they want to please their parents, 41.8% wanted to be safe.

Figure 2.

Personal choice for traditional male circumcision (n = 1,036).

Collated Themes From the Focus Group Discussions

The themes and subthemes were developed during data analysis and they were subsequently collated. They yielded the three negative economic determinants as the overall themes: (a) commercialization and profitmaking, (b) poverty and unemployment, (c) taking health risk for cheaper practices, and the last theme being the (d) actions suggested to prevent the problem.

Commercialization and Profitmaking

The participants in the FGD indicated that some boys could not afford to pay the high amount of money charged by the legal traditional surgeons for the circumcision services provided. Legal traditional surgeons are the registered traditional practitioners according to the circumcision legislation.

The legal traditional surgeons charge high amount of money, about R500 because of that some boys cannot afford to pay their invoices.

The parents of boys are concerned about the new circumcision money business occurring in the present days in their communities. It is a new and unknown initiative of the traditional practitioners which was never seen in the past.

Our parents are telling us that there are new things they don’t know since the beginning of the years 2000s; long ago circumcision was not about money; the money business of traditional practitioners which goes with deaths of circumcision initiates is something strange in our communities.

Poverty and Unemployment

The victims who find themselves admitted in hospitals are from poverty stricken families. Some of them were circumcised without the knowledge of their parents. Especially the boys who are from less privileged, single-parented (mother only) families, are often the most vulnerable.

Some of us were from less privileged families; others were single-parented (mothers only), parents are usually not even aware that the boy is in the initiation school.

Some boys are rushing to be circumcised traditionally because of expecting the privilege of eating in the same dishes of meat and alcohol with the circumcised boys.

Some boys are rushing for circumcision to have a privilege of eating meat and alcohol in the kraal with circumcised boys; boys who are not circumcised stay outside the kraal.

The illegal traditional attendants are often unemployed, unkempt, and they eat food brought home for the initiates.

We have seen unemployed traditional nurses who stay with us in the initiation school, they do not wash their clothes and bodies, and they eat our food brought from home.

Taking Health Risk for Cheaper Practices

The participants in the FGD revealed the prices that the illegal traditional surgeons were charging from the boys who are sometimes of very young age. The illegal traditional surgeons are not registered and their prices are lower than prices of registered traditional surgeons.

The illegal traditional surgeons take any amount of money from the small boys of 11, 12 years have, some charge R150 or even a chicken, the registered traditional surgeons want to be paid a lot of money.

The illegal traditional attendants also introduce drugs and alcohol to the initiates. Initiates who disagree to take drugs face emotional and physical abuse.

The illegal traditional nurses introduce smoking of dagga and drinking of alcohol to initiates, telling them that they won’t feel the pain, those who refuse are emotionally abused and beaten up in the initiation school.

Actions Suggested to Prevent the Problem

Socially accepted actions were suggested during FGDs. There was an appeal from the participants that they would like to have formal sessions at schools to share information on circumcision. These kinds of information sharing sessions would be linked with HIV/AIDS prevention to empower the boys. They stated that already their syllabus is inclusive of Life Orientation Subject which can incorporate circumcision talks.

We are from different communities, we do not talk about circumcision program in a formal way, it would be better if we can have circumcision together with HIV/AIDS sessions here at school in the Life Orientation classes.

Elders are trusted to be responsible traditional attendants in the initiation schools. Grand fathers and uncles are also responsible to take care of initiates in the initiation school.

The matured and experience traditional nurses are responsible; they look after all initiates well including those with single mothers. Some grandfathers and uncles take responsibility of initiates in the initiation school.

The participants suggested that if the government can have a way of paying invoices of the other boys who cannot afford to pay the legal and registered traditional surgeons. Instead of budgeting for unwanted male medical circumcision, the money can pay the registered traditional circumcision surgeons who are practicing safe male circumcision. This can be a strategy of motivating them to circumcise the boys who cannot pay their invoices of R500.

What if the government can assist in paying the trained and registered traditional surgeons to circumcise all those boys who cannot afford to pay R500, moreover, our feeling is that we do not need the hospital circumcision provided by the government.

Discussion

The study discovered that the quest for accomplishment of social respect is an overvalued manhood phenomenon even at the expense of putting the circumcision initiates at risk of circumcision complications and death. The personal choices of boys for traditional male circumcision are influenced by social structures that promote traditional circumcision as the best acceptable practice. This social phenomenon has been hijacked by false traditional practitioners to deceive unsuspecting boys with the intentions to accumulate money. It is the same trend of false practitioners who were identified in Gauteng and Limpopo Provinces who are also the victims of poverty, unemployment, crime, and former prisoners (Sampear, 2015). The participants suggested that Life Orientation syllabus offered at school should incorporate circumcision health sessions to empower the boys. This is a convenient avenue where boys can be exposed to other realistic options about attaining social respect rather than exposing themselves to health risks. For example, career opportunities in different academic fields can be linked to attainment of social respect of individuals in the future. At school, the boys do not have an opportunity to talk about circumcision linked with HIV/AIDS in a formal way. In other terms, the school has no formal sessions to empower boys on circumcision health. Health-promoting school programs can be very instrumental in empowering the boys about good options rather than choosing uninformed risky behaviors (Scriven, 2010). The study also explored the perceived social benefits for choosing traditional circumcision. From the 1,036 boys who answered the questionnaire in a cross-sectional survey, 49.1% responded that they wanted to please their parents. The parents are involved in this perception of social benefits, but some of them are unaware when their children are exposed to risk of being hijacked by illegal traditional surgeons without their consent. Also, from the qualitative point of view, the perceptions and knowledge of boys were collated to form economic variables in the form of themes. The overall findings of this study revealed that poverty, unemployment, illegal actions to gain money, and overvalued quest to attain social respect are the leading socioeconomic determinants that affects negatively with the resultant heath crisis of traditional male circumcision practice. The unregistered traditional surgeons were disregarding the legislation that stipulates that boys should be circumcised at the age of 18 years and above (The Application of Health Standards in Traditional Circumcision Act [Act No. 6 of 2001]). They circumcised boys at very young ages of 11 or 12 years as long as they bring money. This action confirms that unregistered traditional surgeons are making money out of unlawful circumcision practice; they circumcised boys with the intensions to earn money. The unsuspecting initiates pay a lot of money and are transported to remote areas where their families and traditional leaders have no access and are left there without supervision and care (Initiation Summit, 2009). In the FGDs, the participants affirmed that some illegal traditional nurses are forcing initiates to smoke dagga. In the FGDs, it was mentioned that dagga is not a pain killer as they prescribe it. Some of boys understood that dagga is an illicit drug which is detrimental to the lives of people, but the fact that it is forced by traditional nurses in the bush hut is above their control. Some traditional nurses were reported to be assaulting initiates who do not smoke dagga. Initiates who are refusing to smoke dagga are punished in the form of emotional and physical abuse.

Although the police usually close down most of these illegal initiation schools during male circumcision season in OR Tambo, it is sometimes too late for some boys to be saved. In Libode, the culprits (traditional surgeons) were identified to be unskillful, inexperienced, young men who even themselves were circumcised some few months ago. Kepe (2010) reported previously that the main problem is that the circumcision practice has now been commercialized and people are making money profit out of the tradition. He also added that nowadays, especially in urban areas, but in many rural areas as well, the traditional surgeons and the traditional nurses have been demanding cash payment or a combination of cash and alcohol. The participants in this study confirmed that the prices of registered traditional surgeons are very high, amounting up to R500 but the illegal circumcision surgeons accept whatever they can get, R150 or even a chicken as payment for illegal circumcision practice.

The King of AmaMpondo, Ndamase, Ndlovuyezwe at Nyandeni Royal Place declared an average amount that needs to be paid to registered surgeons which is R250.00 per initiate as a resolution to the problem. He further stated that the circumcision fee needs to be the same to all traditional surgeons known to Nyandeni Royal Place. No surgeon should be paid a higher or lower price than others (Ndamase, 2009). The current legislation called The Application of Health Standards in Traditional Circumcision Act (Act No. 6 of 2001) has no provision for the empowerment of the target groups. Instead, the NDoH government has launched the MMC in an effort to curb the spread of heterotransmission of HIV and AIDS in South Africa. The traditional custodians view MMC as another threat to their ancient-old custom, but this view does not bring about a preventive strategy to curb deaths and complications (Mark et al., 2012). The participants who were the boys, the vulnerable group themselves together with the House of Traditional Leaders in the study background indicated their felt need. In a health promotion perspective, the felt need is regarded as an important need to be considered when planning for successful and sustainable health programs. But felt need alone is not sufficient to bring about cost-effective intervention; it should be complemented with normative, comparative, and expressed needs (Scriven, 2010). In the study, 92.2% of boys preferred traditional circumcision, only 4% preferred MMC in Libode, Eastern Cape province in South Africa. It is obvious there is something incorrect with the choice of boys, the high mortality statistics are reported in relation to traditional male circumcision (Eastern Cape Statistics, 2013). Instead, the hijacked traditional practice overwhelms the boys with false social influence to choose fatal circumcision practices provided by illegal circumcisers. Therefore, based on the research findings, the circumcision health promotion program is suggested to deal with the problem holistically (Douglas, 2013). The circumcision health promotion program was developed based on Ottawa Charter principles that can be ultimately be adopted for the district and provincial implementation, utilizing piloted model such as the Traditional Circumcision Forum model in Libode rural communities (WHO, 1986). The Traditional Circumcision Forum was adopted from Beattie’s Health Promotion Model (Scriven, 2010). The effectiveness of this model was based on working together with trained circumcision attendants under the mentorship of cultural-orientated professional health promotion practitioners. Qualified health promotion practitioners are trained to facilitate programs and work with communities as catalysts at a primary level of prevention. They have in-depth specialized knowledge that health promotion is a combination of educational, organizational, economic, motivational, technological, legislative, and political actions designed with consumer participation. Health promotion is a process of enabling individuals, groups, and whole communities to increase control over their health and its determinants, and to improve their health through knowledge, attitudinal, behavioral, social, and environmental changes (Maycock, 2002; WHO, 1986).

Conclusion

The participants in this study were the primary target group, the boys who are directly affected by the problems related to traditional male circumcision deaths and complication. Triangulation was applied by utilizing different methods of data collection to strengthen validity, reliability, and dependability. The social determinants which included the variables for the attainment of social manhood values, benefits such as the attainment of community respect and acceptance of traditional male circumcision for hygienic purposes were described. The negative economic determinants such as poverty, unemployment, commercialization, and profitmaking were explored to be the underlying determinants that contribute to traditional male circumcision complications and death. Suggested socially accepted actions for prevention were also identified which added value in gaining increased community involvement, participation, and ownership that will eventually lead to the complete strategic prevention of unnecessary deaths and related complications in the community by community members themselves. Legislative strategy alone has been proven to be ineffective; it needs to be complemented with economic, educational, motivational, organizational, and technological strategies. Therefore, this study recommends the consideration of socioeconomic determinants by relevant stakeholders associated with primary prevention of traditional male circumcision deaths and complications.

Recommendations

This study recommends a comprehensive health promotion program that is considerate of socioeconomic determinants. Activities involving the communities as important stakeholders for a sustainable preventive program include the following:

A successful circumcision health promotion program depends on the inclusiveness of needs assessment, planning, development, implementation, and evaluation of the program to consider socioeconomic determinants together with community members as participants.

Strengthening of community actions in the use of available resources such as recognized matured and experienced traditional practitioners and empowerment of the community at large to safe guard their traditional circumcision culture against hijacking by illegal traditional practitioners.

At primary level of prevention, the culture-orientated public health workers such as qualified health promotion practitioners need to work in community settings with accepted traditional practitioners as facilitators/catalysts not as experts, and then summon other health professionals such as professional male nurses, environmental health practitioners.

Secondary level of prevention would be the subsequent option in the cases where primary prevention was not followed. For example, medical practitioners and nurses in the health care facilities need to be in readiness to deal with circumcision related problems at an early stage to prevent further complications and deaths.

The House of Traditional Leaders and the Department of Health and are expected to take over custodianship of the practice and funding of the suggested program of action, respectively.

The first primary target group of the program should include boys at schools and be incorporated into their life orientation classes which are already in place; having a goal and behavioral objectives.

The second primary target group of the program should include the traditional practitioners (surgeons and nurses); guided by a program goal and behavioral objectives.

Working together in partnership with other stakeholders such as police, nongovernmental organizations, youth, universities around, and other relevant stakeholders should be strengthened.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Aggleton P. (2007). Just a snip: A social history of male circumcision. Reproductive Health Matters, 15(20), 15-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anike U., Govender I., Ndimande J. V., Tumbo J. (2013). Complications of traditional circumcision amongst young Xhosa males seen at St. Lucy Hospital, Tsolo, Eastern Cape. African Journal of Primary Health Care & Family Medicine, 5, 488. doi: 10.4102/phcfm.v5i1.488 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- The Application of Health Standards in Traditional Circumcision Act. (2001). Act No. 6 of 2001. Eastern Cape, 1-7. Retrieved from http://echealthcrisis.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/Application-of-Health-Standards-in-Traditional-Circumcision-Act_Eastern-Cape_Act-No-6-of-2001.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Babbie E., Mouton J. (2001). The practice of social research. Cape Town, South Africa: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Behrens K. G. (2013). Traditional male circumcision: Balancing cultural rights and the prevention of serious, avoidable harm. South African Medical Journal, 104, 15-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottoman B., Mavundla T. R., Toth F. (2009). Peri-rite psychological issues faced by newly initiated traditionally circumcised South African Xhosa men. Journal of Men’s Health, 6, 28-35. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell J. W. (2009). Research design, qualitative, quantitative and mixed method approaches (3rd ed.). Lincoln, NE and Thousand Oaks, CA: University of Nebraska-Lincoln and SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas M. (2013). An intervention study to develop a male circumcision health promotion programme at Libode rural communities in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa (Doctoral dissertation). Walter Sisulu University, Mthatha, South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- Eastern Cape Statistics. (2013). HIV/AIDS program of safe circumcision (Health presentation, June/July season report). Retrieved from https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/16354/

- Egger G., Spark R., Lawson J., Donovan R. (2005). Health promotion strategies and methods (2nd ed.). Sydney, Australia: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Government of South Africa. (1996). Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996. Pretoria, South Africa: Government Printer. [Google Scholar]

- Gudani. (2011). The analysis of the current Northern Province Circumcision Schools, Act 6 of 1996 and its impact on the initiates. Retrieved from http://www.booksie.com/gudani

- Hargreaves S. (2007). 60% Reduction in HIV risk with male circumcision, says WHO. Lancet, 7, 313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Initiation Summit. (2009). OR Tambo Region, Circumcision Initiation Summit. Mthatha, South Africa: Health Resource Centre, Nelson Mandela Academic Hospital. [Google Scholar]

- Kepe T. (2010). Secrets that kill: Crisis, custodianship and responsibility in ritual male circumcision in the Eastern Cape province, South Africa. Social Science & Medicine, 70, 729-735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labadarious D., Mchiza Z. J. R., Steyn N. P., Gericke G., Maunder Y. D., Parker W. (2011). Food security in South Africa: A review of national survey. Bulletin of the World Health Organisation, 89, 891-899. doi: 10.2471/BLT.11.089243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln Y. S., Guba E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Maluleke T. (2015, December 1). African cultures and the promotion of sexual and reproductive rights. Perspectives, Political Analyses & Commentary. Retrieved from http://thisisafrica.me/african-cultures-promotion-sexual-reproductive-rights/

- Mark D., Middelkoop K., Black S., Roux S., Fleurs L., Wood R., Bekker L. (2012). Low acceptability of medical male circumcision as an HIV/AIDS prevention intervention within a South African community that practices traditional circumcision. South African Medical Journal, 102, 571-573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mavundla T. R., Netswera F. G., Bottoman B., Toth F. (2009). Rationalization of indigenous male circumcision as a sacred religious custom: Health beliefs of Xhosa men in South Africa. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 20, 395-404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maycock B. (2002). Health promotion methods: The science and art of selecting and implementing health promotion methods. Perth, Western Australia, Australia: Curtin University. [Google Scholar]

- Meel B. L. (2010). Traditional male circumcision-related fatalities in the Mthatha area of South Africa. Medicine, Science and the Law, 50, 189-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millions set aside to support initiation schools. (2014, June 13). SA News. Retrieved from http://www.sanews.gov.za/south-africa/13-6-2014

- Ncayiyana D. J. (2011). The illusive promise of circumcision to prevent female-to-male HIV infection—Not the way for South Africa. South African Medical Journal, 101, 775-777. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ndamase N. (2009). Returning the assegai to the kingdom (Sibuyisela umdlanga koMkhulu). Unpublished manuscript.

- Nkwashu G., Sifile L. (2015, July 13). Paid to recruit boys. Sowetan. Retrieved from http://www.pressreader.com/south-africa/sowetan/20150713

- Nqeketo A. (2008). Xhosa male circumcision at the crossroads: Responses by government, traditional authorities and communities to circumcision related injuries and deaths in Eastern Cape Province (Master’s thesis). University of Western Cape, Cape Town, South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- Nwanze O., Mash R. (2012). Evaluation of a project to reduce morbidity and mortality from traditional male circumcision in Umlamli, Eastern Cape, South Africa: Outcome mapping. South African Family Practice, 54, 237-243. [Google Scholar]

- Nyandeni local municipality. (2012-2013). Nyandeni local municipality annual report 2012/13. Retrieved from http://mfma.treasury.gov.za/Documents/06.%20Annual%20Reports/2012-13/02.%20Local%20municipalities/EC155%20Nyandeni/EC155%20Nyandeni%20Annual%20report%202012-13.pdf

- Sampear A. (2015, July 7). Government to criminalize running of illegal initiation schools. SABC News. Retrieved from http://www.sabc.co.za/news/a/cb96cc0049053c0da3e8bb70b5a2a8d2/Govt-to-criminalize-illegal-initiation-schools-20150707

- Scriven A. (2010). Promoting health: A practical guide, Ewles and Simnett (6th ed.). London, England: Baillier Tindal. [Google Scholar]

- Streubert H. J., Carpenter D. R. (2007). Qualitative research in nursing: Advancing the humanistic imperative (4th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. [Google Scholar]

- Venter M. A. (2011). Some views of Xhosa women regarding the initiation of their sons. Koers, 76, 559-575. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (1986). Ottawa Charter for health promotion (First International Conference on Health Promotion). Retrieved from https://www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/health/servicesandsupport/ottawa-charter-for-health-promotion?viewAsPdf=true

- World Health Organization. (2008). Male circumcision policy, practices and services in the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa: Case study. Retrieved from https://www.malecircumcision.org/resource/male-circumcision-policy-practices-and-services-eastern-cape-province-south-africa-case

- World Health Organization. (2012). Outcome of the World Conference on social determinants of health (WHA 65.8, Sixty-Fifth World Health Assembly). Retrieved from http://www.who.int/sdhconference/background/A65_R8-en.pdf