Abstract

Deaths of initiates occurring in the circumcision initiation schools are preventable. Current studies list dehydration as one of the underlying causes of deaths among traditional male circumcision initiates in the Eastern Cape, a province in South Africa, but ways to prevent dehydration in the initiation schools have not been adequately explored. The goals of this study were to (a) explore the underlying determinants of dehydration among initiates aged from 12 to 18 years in the traditional male circumcision initiation schools and (b) determine knowledge of participants on the actions to be taken to prevent dehydration. The study was conducted at Libode, a rural area falling under Nyandeni municipality. A simple random sampling was used to select three focus group discussions with 36 circumcised boys. A purposive sampling was used to select 10 key informants who were matured and experienced people with knowledge of traditional practices and responsible positions in the communities. The research findings indicate that the practice has been neglected to inexperienced, unskillful, and abusive traditional attendants. The overall themes collated included traditional reasons for water restriction, imbalanced food nutrients given to initiates, poor environmental conditions in the initiation hut, and actions that should be taken to prevent dehydration. This article concludes with discussion and recommendation of ways to prevent dehydration of initiates in the form of a comprehensive circumcision health promotion program.

Keywords: traditional male circumcision, prevention, dehydration, initiation school

Introduction

If circumcision initiation is a school, for goodness sake, every school has its written standards. (Key Informant)

Behrens (2014) makes the following statement regarding the effective regulation and management of traditional male circumcision practice:

While traditional male circumcision, as currently practised, causes serious harm, prohibiting this practice is not the only way to prevent harm. With effective regulation and management, the social good of protecting cultural practice can be achieved at the same time ensuring that harm to participants is minimized. (p. 16)

Male circumcision is performed throughout the world for medical, ritual, traditional, and cosmetic reasons. It is estimated that 33.3% of men worldwide have undergone circumcision (Mavundla, Netswera, Bottoman, & Toth, 2009; Senkul et al., 2004). In South Africa, traditional male circumcision is practiced by various cultural groups among boys as a rite of passage from childhood to manhood. The AmaXhosa tribe is one of the ethnic groups that practice traditional circumcision as a male initiation rite in the Eastern Cape province. Traditional male circumcision is regarded as a sacred and compulsory cultural rite intended to prepare initiates for the responsibility of adulthood (Anike, Govender, Ndimande, & Tumbo, 2013). According to the Head of Congress of Traditional Leaders in the Eastern Cape, Chief Mwelo Nonkonyana, if one is not circumcised through the custom of traditional male circumcision in the mountain, one is not regarded as a real man (World Health Organization [WHO], 2008). Young men who are not circumcised are regarded as social outcasts by their peers and suffer the consequences of being called women who gave birth in a hospital ward (abadlezana). Because of this kind of social peer pressure, 92.2% of boys in the Eastern Cape province prefer traditional male circumcision and only 4% accept medical male circumcision (Douglas, 2013; WHO, 2008).

During the circumcision procedure, the traditional surgeon uses an assegai (umdlanga) to cut the foreskin of the penis without any anesthesia in the circumcision initiation school (Mavundla et al., 2009). Initiation schools are regarded as cultural educational institutions, where circumcision initiates are taught about societal norms, customs, and manhood values. Manhood values include being a responsible father in the family and a respected leader in the community. It is the responsibility of the elders to teach the initiates manhood values and concurrently the traditional nurses take care of the circumcision wound by wrapping it with traditional herbs called Helichrysum pedunculatum (izichwe; Bottoman, Mavundla, & Toth, 2009; Gudani, 2011). The ritual is often carried out twice a year, in June and December school holidays to make a provision for convenient periods of time for the school-going boys. Initiation schools are attended in temporary bush huts (amaboma) thatched with grass and situated on hilltops, forests, mountain slopes, or river banks secluded from the community. At the end of the initiation school period, the bush huts are burnt down with fire and the new men (amakrwala) are taken back to the community (Mavundla et al., 2009; WHO, 2008). The initiates stay in the initiation school for about 3 to 4 weeks to learn and observe all the cultural rites, including learning about sexuality. Initiates are trained to be strong, disciplined, to endure pain and hardship in life (Nwanze & Mash, 2012). The potential complication in the aftercare period is dehydration, which is common at initiation schools because initiates are discouraged from drinking fluids. This is believed to prevent frequent urination, prevent wetness (weeping) of the circumcision wound, and also seen as a test of endurance. Two changes in contemporary practice have made dehydration a bigger risk than it was in the past. First, circumcision is now frequently performed in the hotter summer months to accommodate school holidays, whereas in the past, it was performed in autumn and extended to winter for a period of about 6 months. Second, plastic sheeting is now often used to build the initiate’s hut instead of the traditional leaves and grass which were much cooler (WHO, 2008).

The WHO (2008) stated that where government authorities have succeeded in participating in partnership with traditional health practitioners, the greatest success in regulating the practice in the interests of the health of initiates has been achieved. Models for intervention are possible and practicable which take seriously the dictates of tradition, while at the same time, not compromising the health rights of initiates. Therefore, it is a public health concern that a comprehensive health promotion program should be recommended according to the principles of Ottawa Charter to prevent dehydration and other complications in circumcision initiation schools (WHO, 1986).

High Mortality Statistics

High mortality of AmaXhosa circumcision initiates is reported in the media during circumcision seasons in the Eastern Cape province, especially among the AmaMpondo clan in the Pondoland (Kupelo, 2014). These deaths are mainly due to complications of traditional male circumcision such as dehydration, septicemia, gangrene, pneumonia, assault, thromboembolism, and congestive heart failure (Bottoman et al., 2009; Meel, 2010; Meissner & Buso, 2007; Mogotlane, Ntlangulela, & Ogubanjo, 2004; Venter, 2011). Dehydration is one of the more common complications of traditional male circumcision. According to records from the Eastern Cape Provincial Department of Health, over 8% (339) of 4,089 hospital admissions related to traditional circumcisions between June 2006 and December 2011 resulted in death. The mean number of traditional initiates recorded between 2006 and 2011 for the entire Eastern Cape was about 52,668 per year (Eastern Cape Provincial Department of Health, 2011; Table 1).

Table 1.

Statistics of Hospital Admissions, Amputations, and Deaths in the Eastern Cape From June 2006 to December 2011 as a Result of Traditional Male Circumcision.

| Year | Hospital admissions | Amputations | Initiate deaths | Legal initiates | Illegal initiates | Arrests |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 June | 288 | 5 | 26 | 3,470 | 285 | 0 |

| 2006 December | 512 | 7 | 32 | 11,243 | 708 | 0 |

| 2007 June | 329 | 41 | 24 | 12,563 | 1,460 | 0 |

| 2007 December | 311 | 11 | 8 | 33,005 | 1,327 | 0 |

| 2008 June | 360 | 11 | 29 | 14,982 | 1,846 | 51 |

| 2008 December | 267 | 0 | 5 | 40,290 | 553 | 23 |

| 2009 June | 461 | 47 | 55 | 17,538 | 2,470 | 29 |

| 2009 December | 252 | 2 | 36 | 39,581 | 896 | 9 |

| 2010 June | 389 | 22 | 41 | 18,450 | 1,429 | 12 |

| 2010 December | 269 | 1 | 21 | 53,128 | 1,352 | 7 |

| 2011 June | 313 | 10 | 26 | 13,886 | 2,808 | 35 |

| 2011 December | 338 | 10 | 36 | 41,903 | 937 | 24 |

| Total | 4,089 | 167 | 339 | 300,039 | 15,971 | 191 |

The media often report that there are specific culprits who are responsible for these deaths and that the police are investigating them for possible arrest (Kupelo, 2014). The Application of Health Standards in Traditional Circumcision Act (Act No. 6 of 2001) is aimed at regulating the traditional circumcision practice, and setting health standards to be followed by the traditional attendants in the Eastern Cape. The regulation requires that initiates must attend precircumcision medical checkups and traditional surgeons and nurses who contravene this regulation are subject to arrest; however, the rate of arrest is very low (Table 1).

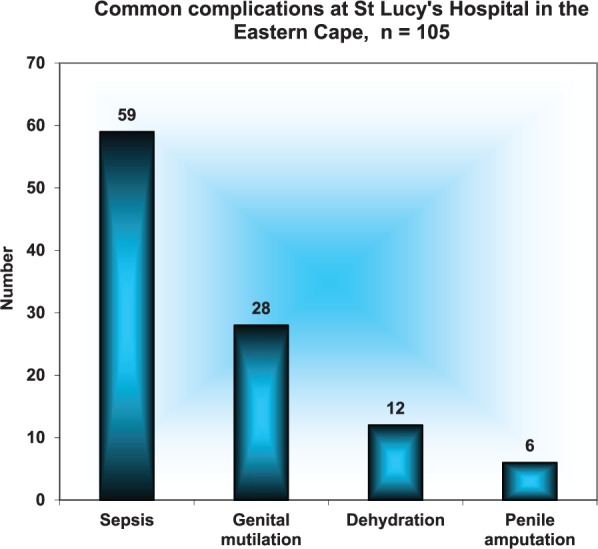

Anike et al. (2013) state that the initiates become significantly dehydrated during their first 2 weeks of seclusion in the belief that this reduces weeping of the wound. There are a number of factors that were identified that are contributing to dehydration; these include deliberate restriction of intake of fluids and minimal or inadequate shelter, especially during summer, which can lead to increased sweating. Severe dehydration may result in renal failure. In a previous study conducted at St. Lucy’s Hospital, a community hospital in Tsolo, Eastern Cape, sepsis (wound infection) was the most common circumcision complication that resulted in patients seeking medical intervention (Anike et al., 2013). Fifty-nine (56.2%) of 105 circumcision related admissions had wound sepsis, followed by genital mutilation in 28 (26.7%) patients. Twelve (11.4%) suffered from dehydration and 6 (5.7%) had amputation of the penis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Traditional circumcision complications admitted at St. Lucy’s Hospital in 2012.

Source. Anike et al. (2013).

Traditional practitioners are often insufficiently trained to perform these surgeries. Poor postoperative management, binding the wound too tightly, and traditional restrictions on drinking water all lead to complications (Anike et al., 2013). Initiates face social pressure to complete the initiation without medical intervention because custom requires secrecy and restricts contact with outsiders or the formal health care system (Behrens, 2014). This often results in initiates seeking medical help too late. The initiates may also become the victims of violence if they ask for medical help outside the initiation school. The WHO states that the ritual of traditional male circumcision is among the most secretive and sacred of rites among the AmaXhosa society, although for the past centuries, these rites played a social role in mediating intergroup relations, renewing unity, and integrating the sociocultural system (WHO, 2008).

According to Behrens (2014), deaths due to dehydration and other preventable complications of traditional circumcision are unethical. The right to participate in traditional practices such as circumcision is included in the South African Constitution but should only be protected insofar as it does not result in serious harm (South African Government, 1996). This does not imply that the practice should be abolished; rather, the practice should be regulated and measures to prevent harm taken and enforced. Mothers and women in South Africa are among concerned groups of people who are desperately in need of urgent solutions to avoid unnecessary deaths of their children in the circumcision initiation schools. Venter (2011) stated that it appears that women’s voices are rarely heard on this issue and the traditional challenge is to keep the boys safe without interfering with the customs. According to the AmaXhosa male circumcision ritual, mothers and married women are not allowed to come close to the initiates or the initiation school. Kupelo (2014) stated that the complexity of this cultural practice delayed the processes of coming up with a feasible and sustainable preventive solution to the problem.

Local government officials in the Eastern Cape province organized numerous meetings with traditional leaders to find a way to tighten the law and make sure that serious complications and deaths were avoided. High mortality statistics in the Eastern Cape has meant that secrecy of this rite is inevitably vanishing and open discussions are occurring at all levels of the society. The crisis has led to many debates in the country among health experts, human rights lawyers, lawmakers, and guardians of local tradition and controversy about the regulation of the practice in South Africa. Both traditional leaders and the government officials often express their shock at the preventable deaths of circumcision initiates (Kupelo, 2014).

The National House of Traditional Leaders have voiced their concern that dying of initiates in the initiation school as a result of dehydration and other traditional circumcision complications is a disgrace to the nation (Initiation Summit, 2009). Traditional circumcision practice remains the pride of the people; the circumcision events are proud moments of the House and the nation at large; this culture is very strong and socially deep rooted. The traditional leaders are regarded as the custodians of the culture and they want to see to it that circumcision culture is maintained from one generation to another (Kepe, 2010).

Men who were circumcised in health facilities (medical male circumcision) and men who underwent traditional circumcision but ended up in the hospital due to circumcision complications are treated as inferior in some areas among AmaXhosa people. This habit applies even if the initiate was admitted due to dehydration, not necessarily related to the circumcised wound. They are not allowed to share certain community activities with the so-called real men. This discriminatory practice often leads to violence and disrespect for uncircumcised older men, even by their circumcised children and young circumcised men in the community (Initiation Summit, 2009).

Although dehydration is associated with restriction of water by traditional nurses, there is a general feeling that stakeholders such as the traditional leaders and parents can play an important role in stopping deaths of circumcision initiates (Kupelo, 2014). According to Niedert and Dorner (2004), environmental factors such as restraints and exposure to excessive heat are associated with dehydration. Under normal circumstances, there are amounts of nutrients that should be taken on an average daily basis to promote health, prevent diseases, and reduce incidence of chronic diseases. Some complementing field work related to dehydration and other circumcision complications was done from 1996 to 1997 in parts of the Eastern, Northern, and Western Cape. The field work was done by medical doctors in cooperation with the Circumcision Task Team, which operated from the Cecilia Makiwane Hospital in Mdantsane, Eastern Cape (Venter, 2011). The initiates were taken care of in the bush hut until the wounds were healed. During that time, the initiates received practical and theoretical instructions about their culture. During the healing period, the drinking of water was restricted. The study reported that in some instances no water was allowed to be drunk for the first 7 days; in some cases, little water was allowed. According to the field work research, the most common reasons for complications were ischemia (starvation of blood supply), infection, gangrene, and dehydration (Venter, 2011).

Method

Study Design

Exploratory and interpretive qualitative methods were followed using focus group discussions and key informant interviews. These methods offered the researcher an opportunity to develop rapport with the communities, to generate networks, and to encourage community involvement in the process. The process of research allowed the respondents to express themselves in their own IsiXhosa language. Emerging questions were engaged in the form of inquiry that support a way of looking at research that honors an inductive style, a focus on individual meaning, and the importance of rendering the complexity of a situation procedures. Data were typically collected in the participants’ settings. Data were analyzed inductively building from particulars to general themes, and the researcher made interpretations of the meaning of the data. The final written report has a flexible structure (Creswell, 2009).

Sampling

The study population comprised circumcised males aged from 12 to 18 years who were attending school and living in the rural communities of Libode, Eastern Cape, South Africa. Libode has a population of 290,390 people and is a district falling under Nyandeni municipality, which is mainly occupied by AmaMpondo. AmaMpondo is a clan within the AmaXhosa tribe (Nyandeni Local Municipality, n.d. [Annual Report, 2012/13]). The study used purposive sampling for key informant interviews and simple random sampling for focus group discussions.

Key Informant Interviews

Key informants were identified from the 10 villages of the Libode District. The key informants were people with responsible positions in the communities who had knowledge related to traditional male circumcision and were willing to share information with the researcher. The key informants included three chiefs, a church pastor (who is also a retired psychologist) and a church elder, one of the king’s liaison officers, three life orientation teachers, and one senior education specialist. Four key informants were females and six were males. Ten key informant interviews were conducted using a semistructured interview guide.

Focus Group Discussions

Focus group discussions were used to explore the perceptions of only circumcised boys (abafana) regarding restriction of drinking water while in the initiation schools. As circumcision is a sensitive subject among the AmaXhosa and traditional leaders, only circumcised boys were eligible to participate in the study. One focus group discussion was conducted in each school and 3 schools were selected using simple random selection from a total of 22 schools. There were 12 participants per focus group; a total of 36 circumcised boys participated in the three focus group discussions. Only circumcised boys were part of the three focus group discussion because the two questions that were asked were only relevant to those who had already experienced traditional circumcision. These circumcised boys went through traditional circumcision processes and they knew what was happening in the initiation school. A digital voice recorder was used to record discussions and the data were transcribed verbatim and translated from IsiXhosa into English.

Ethics

The study proposal was submitted to the Research Committee of Walter Sisulu University for registration and approval. Ethical approval was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee of the University. Walter Sisulu University Senate Ethics Committee issued a certificate for the study to proceed. No individual names of the participants were used in this study. All participants signed the consent forms and those less than 18 years of age had written consent to participate in the study from their parents or guardians and the school principal. Permission to conduct the study was sought from the House of Traditional Leaders, Department of Education, community and youth leaders.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using Tesch’s eight-steps analysis method. Tesch’s eight-steps analysis method involves the integration and synthesis of narrative and nonnumeric data which are then reduced into themes (Creswell, 2009). As the interviews were conducted, responses were reviewed to identify additional questions that needed to be used or to offer descriptions of what was identified. The researcher subsequently read all the data to gain a general sense of the information and to begin to interpret their overall meaning. The information was coded and analyzed, and then grouped into themes. A limitation of the study is that among AmaXhosa people, male circumcision is performed secretly away from the females. There is a possibility that some key informants, especially females, could not disclose all the information openly due to secretiveness of the circumcision custom. Another limitation is that some words are expressed in English and IsiXhosa, but it is not only the AmaXhosa tribe that is affected with the problems related to traditional male circumcision in South Africa.

Trustworthiness of Findings

Both the findings from the focus group discussions and key informant interviews were integrated to guarantee trustworthiness of the study (Babbie & Mouton, 2001). The researcher used data triangulation for the purpose of generating meaningful data and to ensure validity and reliability of the findings (Streubert & Carpenter, 2007). Guba’s model of trustworthiness was also used, which rests on credibility, transferability, confirmability, and dependability (Lincoln & Guba, 1985).

Results

The analysis yielded four overall themes as follows: (a) Traditional reasons for water restriction, (b) Imbalanced diet given to initiates, (c) Poor environmental conditions in the initiation schools, and (d) Action that should be taken to prevent dehydration.

Traditional Reasons for Water Restriction

According to the participants, there were several reasons why the traditional nurses were restricting water consumption by circumcision initiates. The circumcised peers described the restriction of water as being the fulfillment of the custom (isiko). They were knowledgeable of the fact that over restriction of water was associated with thirst and maltreatment.

It happens sometimes that the initiate is so thirsty in the bush because of over restriction of water and maltreatment; the traditional nurses do not give him water, they say the custom (isiko) does not allow circumcision initiate to drink water. (Focus Group Discussion)

The participants were aware that some initiates required hospital admission for the treatment of dehydration as a result of water restriction. All the focus group participants explained their fears of being rejected after hospitalization. All initiates, irrespective of medical conditions, were expected to finish the initiation process in the bush hut without any intervention of the Westernized health care system.

In some cases the initiate collapses because of lack of water in the body, he needs a drip in the hospital, but the initiate fear rejection after discharge from the western cultured hospitals. (Focus Group Discussion)

Some of the key informants described a perception of associating a wet wound with drinking of clean water. In this perception, there were also manifestations of ignorance or lack of basic principles of hygiene and nutrition because instead of giving clean drinking water, initiates were given sips of water mixed with soil to drink. The key informants agreed that in their experience, the initiates were given contaminated water to drink just to moisten their tongues in an effort to discourage drinking of clean water.

Drinking of clean water is not allowed because they say it delays wound healing; the wound becomes wet; the circumcision initiates are only given sips of water mixed with soil, just to wet their tongues. (Key Informant)

Other key informants stated that the source of reference for the restriction of water is not known. They demonstrated their understanding of the importance of having a known reference on which the practice should be based. Their perception about ancient times (olden days) was different from that of modern times. They argued that if there were no written information available about water restriction, the details about how water was restricted in the olden days were definitely not available as well. Some key informants agreed that initiates were restricted to have access to adequate supplies of clean water and are only allowed to drink sips of contaminated water. Others were against this practice and did not understand where it originated.

Where is this information coming from, that our children must not to drink clean water? There is no written information about this traditional practice of water restriction; it is just the word of mouth from certain individuals. Look, we are not living in ancient times. No! No! (Key Informant)

None of the participants knew where the idea of water restriction came from; elderly respondents were never informed about the origin of the idea. The response from another key informant was that the idea of water restriction against initiates was a myth (intsomi) and superstition (inkolelelo). The idea had no tangible background and evidence; it was not known where it came from.

Restriction of water against the initiates is a myth; we do not have written records of this myth and superstition; Oh, forget about it, who started it? We are now grey headed; nobody knows who came with the idea. (Key Informant)

One key informant explained that they visited Mthatha Hospital with the AmaMpondo King of Enyandeni Royal Place. In the hospital, the details of medical problems related to traditional circumcision were explained to them. One of these problems was dehydration as a result of water restriction in the circumcision initiation school. The AmaMpondo king and the key informant were shocked to observe their children in such pain and having complications.

There is a problem of dehydration if an initiate is not allowed to drink water. Meanwhile the child is in pain, we were shocked in Mthatha Hospital when we took a visit with the King of Enyandeni Royal Place to see the children in such serious conditions and pain. (Key Informant)

The participants described a culture that was not known in their place of birth. They called it a “prison culture.” They explained that they saw a strange manifestation of prison culture, where newly initiated young men walked in queues like prisoners. The participants revealed the coincidence of high crime rate in their communities and associated it with this strange prison culture infiltration. Key informants mentioned rape of women repeatedly. Informants reported that families had lost their understanding of what is taught to their children in the circumcision initiation school in Libode rural communities.

There are families who say they no longer understand what is happening in the bush, they feel that traditional circumcision is now infiltrated with prison culture; some individuals are killing the children. We see something strange nowadays, our children when they are from initiation school walking in queues like prisoners; What are they being taught away from everybody? We know, they teach them crime, in the same era we see high number of rape cases in our communities. (Key Informant)

Imbalanced Diet Given to Initiates

One participant observed a common practice in the circumcision initiation schools, where the initiates were given half cooked maize (inkobe ezinqum) to eat. The participant explained that the initiates were supposed to be given good food and fluids with recommended nutrients to speed up the wound healing process. Instead, they were given half cooked maize which is full of starch and very hard to chew. In addition to that any food with salt was not allowed.

This is common in this area of Pondoland; initiates are given half cooked maize (inkobe ezinqum), food with no salt. I said that an initiate should eat food with nutritious substances and drink fruit juices in order to speed up the healing process. (Key Informant)

Poor Environmental Conditions in the Initiation Schools

Participants described the environmental conditions of the initiation schools as poor. Boys grew up at home sleeping on comfortable beds but all of a sudden, they find themselves sleeping on the dusty ground in a small plastic-covered bush hut. They called the bush hut “amatyotyombe” which means shacks found in the informal settlements. The participants stated that children are not used to sleep on the dusty ground nowadays.

Apart from that, a child who grew up well, used to sleep on a bed at home then all of a sudden, the child is instructed to sleep on the dusty ground and dwell in small plastic covered bush huts (amatyotyombe). (Key Informant)

The participants also stated that the plastic-covered bush hut becomes very cold in winter and very hot in summer which added up more suffering of the initiates. The participants described such environmental conditions as unfavorable to the initiates and in summer contributing to sweating and dehydration.

In summer these plastic covered bush huts are very hot and in winter there are very cold. Most of them like in December summer holidays, Yhoo!!! it very hot and contribute to sweating and dehydration of our children in the bush. (Key Informant)

Action to Be Taken to Prevent Dehydration

All the participants agreed that action should be taken to advocate for initiates to be allowed to drink clean water in the initiation school. Reports about the causes of death of initiates were available in the media every circumcision season in the Eastern Cape province. Participants said that everybody listens to the television and radio; they have heard that dehydration is one of the causes of deaths related to traditional circumcision.

An initiate should be given some amount of clean water, just a cup of water at a time. There is a problem of dehydration nowadays in the initiation schools, we heard from the TV and radio that many boys are dying because of this dehydration. (Focus Group Discussion)

All participants confirmed that in Libode, traditional nurses are young and inexperienced in taking care of the initiates. They further explained that an experienced traditional nurse uses his discretion and protects the initiates. In many communities in the Eastern Cape where traditional nurses are elderly men, deaths of initiates are prevented. The participants also agreed that they experienced no problems under the care of elderly traditional nurses.

In my village, the traditional nurse is an elderly man, he understands, he allowed us to drink clean water as much as we want, we never had problems, but in some places here, the traditional nurses are young people like us, some of them are of the same age. (Focus Group Discussion)

It is important to note that participants observed an experienced traditional nurse who disregarded the myth. He did not allow children under his custody to die of thirst; he gave them water to drink. Circumcision deaths are not reported everywhere in the Eastern Cape, for example, there are areas where no deaths were ever recorded.

I always tell the boys in the classroom that in Cofimvaba where I am coming from, there are no circumcision deaths. We have mature, adult traditional surgeons and traditional nurses who take care of the initiates. (Key Informant)

One key informant related circumcision initiation school to the ordinary schools in the communities where there are written standards, a curriculum, and syllabus. According to the traditional way, there are no written standards available for boys and parents to read before and after the initiation school. The affected boys are school-going boys and they are used to reading instructions and written standards at school.

If circumcision initiation is a school, for goodness sake; every school has its written standards. We are no longer illiterate anymore; gone are those days; how can a school be continued without written standards; for that matter these initiates are school boys; they are used to written standards. (Key Informant)

The key informant revealed the general feeling of mothers. She confirmed that she was speaking on behalf of mothers. Her argument was that there was a concern that Christian values were not applicable in the traditional circumcision initiation school. According to the AmaXhosa culture, mothers are not allowed to visit their children in the initiation schools. Mothers were expected to be silent about what is happening in the traditional male circumcision initiation but what was happening was manifested in the actions of the initiates after the initiation process.

Why is it that we do not have pastors in the bush to teach our children good values because these are children of Christians, I am talking on behalf of mothers because I am a mother and this culture does not allow us to visit our children, We may be silent of what they say but the actions of children are not silent. (Key Informant)

The participants demanded health personnel to train traditional attendants about infection control. The health personnel should respect the culture and the participants who do not want to be circumcised by the medical practitioners.

Health staff like doctors and nurses must only show traditional surgeons of how to prevent infection, but some of them do not understand our culture and others undermine our culture. We do not want to be circumcised by medical doctors, we want our traditional surgeons (iingcibi), and this is our custom (isiko lethu). (Focus Group Discussion)

Discussion

The notion of restriction of water during circumcision initiation is based on a misconception that appears to be passed from one generation to another. Participants reported that the restriction of water was at the discretion of experienced and mature individual traditional practitioners. The experienced traditional nurses do not allow over restriction of water which leads to dehydration. There are some restrictions in the traditional male circumcision practice, not only limited to restriction of fluids, clean water, and certain foods. The restrictions are described as the fulfillment of the custom (isiko) to instill manhood values in the form of discipline and endurance. For example, mothers of the initiates are not allowed to visit their children in the initiation school when manhood values and hard discipline is inculcated (Venter, 2011).

The study identified that traditional attendants in Libode were young, inexperienced, and abusive. Hence, they were not teaching the initiates manhood values according to the custom. For example, the traditional attendants thought that the wound became wet (weeping wound) because of consumption of clean drinking water. They restricted water without using any discretion or observation even if an initiate showed signs of severe thirst and dehydration. The key informant and focus group participants were aware that death due to dehydration was the consequence of water and fluid restriction during the first 2 weeks of surgery but not an intended outcome. In another study, Bottoman et al. (2009) had one participant who stated that he was afraid of what would happen to him if he became dehydrated by not drinking water. He did not sleep at night, fearing what would happen to him if he did not recover and then ended up in the hospital. The fear of being ostracized for failing the manhood test is often regarded as too great for the boys to contemplate.

Participants stated that initiates should be given reasonable amounts of drinking water in the bush hut to prevent dehydration. In Libode, the culprits (traditional nurses) were described as unskillful, inexperienced, young men who themselves were circumcised only a few months ago. They were also said to be the victims of poverty, unemployment, and crime and included former prisoners. The research findings indicated that elderly men and fathers neglected their role of being traditional nurses. Parents do not understand what is happening; boys are influenced by peer pressure to undergo traditional circumcision and uncircumcised fathers are disrespected by their own circumcised children. The participants identified a new culture in their place of birth, which they called “a prison culture.”

Opportunism was manifested where the culprits asserted themselves as traditional nurses but instead of instilling manhood values, the prison culture was demonstrated. Mothers of traditionally circumcised initiates are not allowed to visit their children in the initiation school. In fact, it was notable that some myths and superstitions are profoundly associated with the culture.

The study suggests action that should be taken to advocate for initiates to be allowed to drink clean water in the initiation school. There should be advocacy for policy makers in the public sector to proclaim statements from the policy, for example, circumcision initiates must be allowed to drink fluids and eat a balanced diet. Culture orientated public health practitioners comprising of health promotion practitioners, environmental health practitioners, and community nurses are identified to be the relevant stakeholders to work together with traditional practitioners at the primary health care level. The communities need to be empowered to own and sustain the preventive program and its policies. At a secondary level of primary health care, the health care system comprising medical practitioners and urologists needs to play its role in advising the traditional leaders as custodians of the culture and alarming them in epidemiological trend of circumcision in general. Police patrol should be strengthened to guard against violation of law by culprits responsible for assaults, restraints, and any form of abuse targeted to circumcision initiates. Ottawa Charter of health promotion espoused by WHO encourages all countries to embark on a process of enabling people to have control over and improve their own health (WHO, 1986).

It is crucial for the relevant stakeholders mentioned in this study to work together and simplify the program at a primary level of prevention and empower the target groups. According to Douglas (2013), it is a common belief among AmaXhosa people that during the first week of circumcision, boys should not be given a balanced diet. For example, the initiates are only given half cooked maize (inkobe ezinqum) for the first 2 weeks until a ceremony called ukojisa (roasting of meat) has been done. This is a very hard experience especially for boys in modern days who are not used to eating half cooked maize. The participants stated clearly that they were not living in ancient times (olden days) and that every school has its written standards, knowledge, and skills taught to learners in the form of school curriculum.

Conclusion

The participants in this study were respected community leaders and children who freely gave valid information. Triangulation was applied by utilizing different methods of data collection to strengthen validity, reliability, and dependability. According to the findings of this study, dehydration among traditional male circumcision initiates is caused by restriction of clean drinking water, any other fluids, and certain foods, such as fresh fruit and vegetables especially during the first 2 weeks in the initiation school. The underlying social determinants include peer pressure to fulfill the requirements of the custom, fear of rejection by peers should one fail the cultural prescriptions, ignorance and predetermined myth and superstition that drinking of water causes a weeping wound, misconceptions carried from one generation to another, neglect of after care and wound management by the young and inexperienced traditional attendants, and abuse and maltreatment by traditional attendants.

Recommendations

This study recommends a comprehensive health promotion program be developed to prevent dehydration in initiation schools. Activities involving community stakeholders for a sustainable preventive program include the following:

A professionally designed health promotion program aimed at achieving health standards through behavioral objectives primarily targeting school boys and traditional practitioners.

Culture-orientated public health practitioners such as male health promotion practitioners, environmental health practitioners, and community nurse practitioners should be encouraged to work together with traditional practitioners to prevent dehydration and any circumcision health-related problems.

Policy makers need to build and proclaim policy statements that obligate traditional practitioners to allow circumcision initiates to drink fluids, clean water, and consume nutritious foods according to the basic principles of nutrition and sick initiates should be allowed to access health care services freely without ostracism.

Appointments of socially accepted trained and experienced traditional practitioners to take responsibility and custody of circumcision initiates in the initiation school.

Medical practitioners need to play a meaningful role in advising the traditional leaders as custodians of the culture of the epidemiological trends of circumcision complications and dehydration.

Police should investigate assaults, restraints, and any form of abuse targeted at circumcision initiates.

Relevant stakeholders including the religious organization such as the Christian churches and parents should be allowed to play a meaningful role in protecting the children and affording them good shelter while in the initiation schools.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Anike U., Govender I., Ndimande J. V., Tumbo J. (2013). Complications of traditional circumcision amongst young Xhosa males seen at St. Lucy Hospital, Tsolo, Eastern Cape. African Journal Primary Health Care & Family Medicine, 5. doi: 10.4102/phcfm.v5i1.488 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- The Application of Health Standards in Traditional Circumcision Act. (2001). Act No. 6 of 2001, “Eastern Cape.” Retrieved from http://echealthcrisis.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/Application-of-Health-Standards-in-Traditional-Circumcision-Act_Eastern-Cape_Act-No-6-of-2001.pdf

- Babbie E., Mouton J. (2001). The practice of social research. Cape Town, South Africa: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Behrens K. G. (2014). Traditional male circumcision: Balancing cultural rights and the prevention of serious, avoidable harm. South African Medical Journal, 104, 15-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottoman B., Mavundla T. R., Toth F. (2009). Peri-rite psychological issues faced by newly initiated traditionally circumcised South African Xhosa men. Journal of Men’s Health, 6, 28-35. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell J. W. (2009). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed method approaches (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas M. (2013). An intervention study to develop a male circumcision health promotion programme at Libode rural communities in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa (Doctoral dissertation). Walter Sisulu University, Mthatha, South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- Eastern Cape Provincial Department of Health. (2011). Circumcision statistics, South Africa. Retrieved from https://pmg.org.za/committee/16354

- Gudani. (2011). The analysis of the current Northern Province Circumcision Schools, Act 6 of 1996 and its impact on the initiates. Retrieved from http://www.booksie.com/gudani

- Initiation Summit. (2009). OR Tambo Region, Circumcision Initiation Summit. Mthatha, South Africa: Health Resource Centre, Nelson Mandela Academic Hospital. [Google Scholar]

- Kepe T. (2010). “Secrets” that kill: Crisis, custodianship and responsibility in ritual male circumcision in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. Social Science & Medicine, 70, 729-735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupelo S. (2014, June 30). Soaring initiate deaths “a crisis.” DispatchLive. Retrieved from http://www.dispatchlive.co.za/news/soaring-initiate-deaths-a-crisis/

- Lincoln Y. S., Guba E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage; Retrived from http://www.qualres.org/HomeLinc-3684.html [Google Scholar]

- Mavundla T. R., Netswera F. G., Bottoman B., Toth F. (2009). Rationalization of indigenous male circumcision as a sacred religious custom: Health beliefs of Xhosa men in South Africa. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 20, 395-404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meel B. L. (2010). Traditional male circumcision-related fatalities in the Mthatha area of South Africa. Medicine, Science and the Law, 50, 189-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meissner O., Buso D. L. (2007). Traditional male circumcision in the Eastern Cape: Scourge or blessing? South African Medical Journal, 97, 371-373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mogotlane S. M., Ntlangulela J. T., Ogubanjo B. G. (2004). Mortality and morbidity among traditionally circumcised Xhosa boys in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. Curationis, 27, 57-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niedert K. C., Dorner B. (2004). Nutrition care of the older adult: A handbook for dietetics professionals working throughout the continuum of care (2nd ed.). Chicago, IL: American Dietetic Association. [Google Scholar]

- Nwanze O., Mash R. (2012). Evaluation of a project to reduce morbidity and mortality from traditional male circumcision in Umlamli, Eastern Cape, South Africa: Outcome mapping. South African Family Practice, 54, 237-243. [Google Scholar]

- Nyandeni Local Municipality. (n.d.). Annual report 2012/13. Retrieved from http://mfma.treasury.gov.za/Documents/06.%20Annual%20Reports/2012-13/02.%20Local%20municipalities/EC155%20Nyandeni/EC155%20Nyandeni%20Annual%20report%202012-13.pdf

- Senkul T., Iseri C., Sen B., Karademir K., Saragoglu F., Dogan E. (2004). Circumcision in adult: Effect on sexual function. Adult Urology, 6, 155-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- South African Government. (1996). The Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996. Retrieved from http://www.gov.za/documents/constitution/constitution-republic-south-africa-1996-1

- Streubert H. J., Carpenter D. R. (2007). Qualitative research in nursing: Advancing the humanistic imperative (4th ed.) Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. [Google Scholar]

- Venter M. A. (2011). Some views of Xhosa women regarding the initiation of their sons. Koers, 76, 559-575. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (1986). The Ottawa charter for health promotion (First International Conference on Health Promotion). Retrieved from http://www.who.int/healthpromotion/conferences/previous/ottawa/en/

- World Health Organization. (2008). Male circumcision policy, practices and services in the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa: Case Study. Retrieved from https://www.malecircumcision.org/resource/male-circumcision-policy-practices-and-services-eastern-cape-province-south-africa-case