Abstract

Species differences in renal drug transporters continue to plague drug development with animal models failing to adequately predict renal drug toxicity. For example, adefovir, a renally excreted antiviral drug, failed clinical studies for human immunodeficiency virus due to pronounced nephrotoxicity in humans. In this study, we demonstrated that there are large species differences in the kinetics of interactions of a key class of antiviral drugs, acyclic nucleoside phosphonates (ANPs), with organic anion transporter 1 [(OAT1) SLC22A6] and identified a key amino acid residue responsible for these differences. In OAT1 stably transfected human embryonic kidney 293 cells, the Km value of tenofovir for human OAT1 (hOAT1) was significantly lower than for OAT1 orthologs from common preclinical animals, including cynomolgus monkey, mouse, rat, and dog. Chimeric and site-directed mutagenesis studies along with comparative structure modeling identified serine at position 203 (S203) in hOAT1 as a determinant of its lower Km value. Furthermore, S203 is conserved in apes, and in contrast alanine at the equivalent position is conserved in preclinical animals and Old World monkeys, the most related primates to apes. Intriguingly, transport efficiencies are significantly higher for OAT1 orthologs from apes with high serum uric acid (SUA) levels than for the orthologs from species with low serum uric acid levels. In conclusion, our data provide a molecular mechanism underlying species differences in renal accumulation of nephrotoxic ANPs and a novel insight into OAT1 transport function in primate evolution.

Introduction

Acyclic nucleoside phosphonates (ANPs), including adefovir, cidofovir and tenofovir, have become a key class of antiviral drugs due to many unique features such as their prolonged action and low resistance profile (De Clercq and Holý, 2005). However, nephrotoxicity remains a concern for the ANPs. For example, adefovir was not approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of human immunodeficiency virus infection because of pronounced nephrotoxicity at dosages of 60–120 mg/day (Mellors, 1999). Subsequently, the drug was approved at 10 mg/day for the treatment of hepatitis B infections. However, even at low doses, the drug still has the potential to cause nephrotoxicity after chronic administration, particularly in patients with pre-existing kidney disease. Furthermore, the product label for cidofovir, used in the treatment of cytomegalovirus, includes a recommendation that probenecid be coadministered with the drug. Finally, although rare, tenofovir has been associated with nephrotoxicity, including in Fanconi-Bickel syndrome (Dahlin et al., 2015).

The mechanism for nephrotoxicity of ANPs is related to accumulation of the drugs in renal proximal tubules (De Clercq and Holý, 2005). Studies suggest that cytotoxicity of these antiviral agents is increased 100-fold in cells expressing organic anion transporter 1 (OAT1) (Ho et al., 2000). In fact, OAT1, which is highly expressed in the basolateral membrane of renal tubule epithelial cells, plays an important role in the uptake of ANPs into proximal tubular cells (De Clercq and Holý, 2005; Uwai et al., 2007). OAT1-mediated accumulation of adefovir and cidofovir is associated with increased cellular toxicity in in vitro assays (Ho et al., 2000) and as noted, probenecid, a potent inhibitor of OAT1, reduces the nephrotoxic effects of cidofovir in both cynomolgus monkeys and humans (Lacy et al., 1998).

Thus, the question of whether preclinical animal species orthologs of OAT1 exhibit transport kinetics similar to the human ortholog becomes important for predicting nephrotoxicity in humans. Currently, our knowledge of the differences in the antiviral drug transport kinetics of OAT1 among human and preclinical animal species orthologs is limited. For example, the Km value of human OAT1 (hOAT1) for cidofovir and adefovir was found to be 5- to 9-fold lower compared with rat OAT1 (Cihlar et al., 1999). On the other hand, there were minimal species differences between hOAT1 and the ortholog from cynomolgus monkey in terms of localization in the kidney, as well as its Km value and transport efficiency (Vmax/Km) for 11 substrates, including two antiviral drugs, acyclovir and zidovudine (Tahara et al., 2005).

Here, we hypothesized that there are large species differences in the kinetics of ANP uptake into cells via OAT1, which may contribute to species differences in renal accumulation of these potentially nephrotoxic antiviral drugs. We report that hOAT1 had a significantly lower Km value for the antiviral drug tenofovir in comparison with OAT1 species orthologs from four commonly used preclinical animals, including cynomolgus monkey, mouse, rat, and dog. We demonstrated that serine at position 203 (S203), a residue predicted to be in the binding site of hOAT1, was essential for a lower tenofovir Km value than alanine at the equivalent position. In addition, tenofovir transport efficiency (Vmax/Km) was higher for hOAT1 than for orthologs from the four preclinical animal species. Finally, we explored primate evolution of the transporter and noted that all apes consistently have S203, whereas most Old and New World monkeys have alanine at position 203 (A203). One of the remarkable characteristics of apes is that they have lost functional uricase during evolution (Kratzer et al., 2014), and consequently their serum uric acid (SUA) levels are significantly higher than species with uricase activity. Although speculative, our data suggest that S203 in OAT1, which results in greater efficiency of transport, evolved to aid apes in handling the higher levels of uric acid associated with the loss of uricase.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals and Reagents

Adefovir, cidofovir, 6-carboxyfluorescein (6CF), and glutaric acid were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Tenofovir was purchased from Carbosynth (Berkshire, United Kingdom). α-Ketoglutarate was purchased from Spectrum Chemicals & Laboratory Products (Gardena, CA). [3H]-tenofovir and [14C]-uric acid were purchased from American Radiolabeled Chemicals (St. Louis, MO). The specific activities of these compounds were 10 and 50 mCi/mmol, respectively. [3H]-adefovir and [3H]-cidofovir were purchased from Moravek Inc. (Brea, CA). The specific activities of these compounds were 16.6 and 30.5 Ci/mmol, respectively. [3H]-p-aminohippuric acid was purchased from PerkinElmer Health Sciences Inc. (Shelton, CT) with specific activity of 5 Ci/mmol. Cynomolgus monkey and dog whole kidneys were purchased from BioreclamationIVT (New York, NY). Samples of mouse and rat whole kidneys were provided by AstraZeneca (Waltham, MA).

Blast and Sequence Alignment.

Human OAT1 amino acid sequence from 196 to 210 (GMALAGISLNCMTLN) was used to perform protein blast using the online tool BLAST (Altschul et al., 1997) (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi?PROGRAM=blastp&PAGE_TYPE=BlastSearch&LINK_LOC=blasthome) to identify species with verified or predicted OAT1 amino acid sequences. OAT1 orthologs from proboscis monkey (Nasalis larvatus), hamadryas baboon (Papio hamadryas), and small-eared galago (Otolemur garnettii) were obtained from UCSC Genome Browser (https://genome.ucsc.edu/). OAT1 amino acid sequences were aligned using Clustal Omega (Goujon et al., 2010; Sievers et al., 2011; McWilliam et al., 2013) (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalo/).

Cloning and Establishment of Expression Vectors of Human, Cynomolgus Monkey, Mouse, Rat, Dog, Chimpanzee, Gorilla, Gibbon, Orangutan, and Galago OAT1 Orthologs.

Polymerase chain reaction primers (Supplemental Table 1) based on the coding regions of OAT1 of human (NM_153276.2) was designed to amplify full-length fragments from our previous work (Fujita et al., 2005). Polymerase chain reaction primers (Supplemental Table 1) based on the coding regions of cynomolgus monkey (NM_001287697.1), rat (NM_017224.2), and dog (XM_533258.5) were designed to amplify full-length fragments from kidney cDNAs (Zyagen, San Diego, CA) from corresponding species. The coding regions of mouse Oat1 (BC021647.1) were amplified from cDNA clones purchased from OriGene (Rockville, MD). The coding sequences of OAT1 from chimpanzee (XM_001160252.4), western lowland gorilla (XM_019037481.1), and northern white-cheeked gibbon (XM_003274115.1) were generated from hOAT1 using the Q5 Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA). Sumatran orangutan OAT1 (XM_002821628.1) and small-eared galago (XM_003798698.1) were synthesized by GenScript USA Inc. (Piscataway, NJ). OAT1 coding sequences were inserted in the pcDNA5/FRT plasmid to generate expression constructs.

Construction of Chimeric Transporters.

Amino acid sequences of hOAT1 and cynomolgus monkey OAT1 (cyOAT1) were aligned and 17 different amino acids were identified between the two species. Chimeric proteins were constructed using NEBuilder HiFi DNA Assembly Cloning Kit (New England Biolabs). Three chimeric transporters (human 1–136 + cynomolgus monkey 137–550; human 1–300 + cynomolgus monkey 301–550; cynomolgus monkey 1–400 + human 401–550) were constructed. The sequence of each chimera was confirmed by DNA sequencing (MCLAB, South San Francisco, CA).

Cloning of Human and Cynomolgus Monkey OAT1 Mutants.

Human OAT1 S203A and S203T, and cynomolgus monkey OAT1 S198A, A203S, I254V, and V256A were generated using the Q5 Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (New England Biolabs) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Sequences were confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Transfection and Establishment of Stable Cell Lines.

Genes encoding OAT1 orthologs and mutants were transfected in human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK293)-Flp-In cells (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) using Lipofectamine LTX (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. HEK293-Flp-In cells stably transfected with the empty vector or the vector containing the genes of interest were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, penicillin (100 U/ml), streptomycin (100 μg/ml), sodium pyruvate (110 μg/ml), and hygromycin B (100 μg/ml) at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2.

Inhibition of hOAT1-Mediated 6CF Uptake by Adefovir, Cidofovir, and Tenofovir.

The method as described in Liang et al., (2015) was used with minor modifications. Cells were seeded in black wall poly-D-lysine-coated 96-well plates for 24 hours to reach 95% confluence. Before the uptake experiment, cell culture medium was removed and the cells were washed with Hanks’ balanced salt solution (HBSS). The inhibition of the uptake of 1 μM 6CF by OAT1 was performed at 37°C in the presence of antiviral drugs adefovir, cidofovir, and tenofovir at desired concentrations. The uptake was terminated at 1 minute. Cells were washed twice with ice-cold HBSS buffer. The IC50 values were calculated using GraphPad Prism 7 software (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA).

Transporter Uptake Studies.

The uptake was initiated by incubating transiently or stably overexpressing cell lines with HBSS containing desired concentrations of a substrate. Cells were seeded in black wall poly-D-lysine-coated 96-well plates for 24 hours to reach 95% confluence. Before the uptake experiment, cell culture medium was removed and the cells were washed with HBSS. The details for drug concentrations and uptake time are described in Results and the specific figures being cited. For the uric acid uptake assay, unlabeled uric acid was dissolved in 0.1 N NaOH and added to obtain designed concentrations in HBSS buffer plus 10 mM HEPES to maintain pH 7.4. The uptake was performed at 37°C, and then the cells were washed three times with ice-cold HBSS. Next, the cells were lysed with lysis buffer containing 0.1 N NaOH and 0.1% SDS, and the radioactivity in the lysate was determined by liquid scintillation counting. For the transporter study, the Km and Vmax values were calculated by fitting the data to a Michaelis-Menten equation using GraphPad Prism 7.

OAT1 Comparative Structure Modeling and Docking.

Human OAT1 was modeled using the 2.9 Å crystal structure of a high-affinity phosphate transporter from Piriformospora indica, in an inward-facing occluded state, with bound phosphate (Pedersen et al., 2013). The final sequence alignment was obtained by manual refinement of gaps in the output from the PROMALS3D (Pei et al., 2008) and MUSCLE (Edgar, 2004) web servers. One hundred models were generated using the automodel class in MODELER 9.16 (Sali and Blundell, 1993) and evaluated using the normalized discrete optimized protein energy (zDOPE) potential (Shen and Sali, 2006). The top-scoring model was then used for the prediction of a putative binding site near the location of the crystallographic phosphate with the FTMap web server (Kozakov et al., 2015). Tenofovir was docked against the binding site with UCSF DOCK 3.6 (Coleman et al., 2013).

Membrane Protein Extraction and Quantification.

The total membrane proteins were extracted using the ProteoExtract Kit (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA). The final membrane fraction was diluted to a working concentration of 2 µg membrane protein per microliter as quantified by bicinchoninic acid assay. Total membrane proteins were reduced, denatured, alkylated, and digested in triplicate as per our previously reported protocol (Prasad et al., 2016). The OAT1 surrogate peptide, TSLAVLGK, generated by trypsin digestion, was quantified by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry, where the synthetic light peptide was used as the calibrator. The corresponding heavy peptide labeled at [13C615N2]-lysine was used as the internal standard. Peptide quantification was performed using the Waters Xevo TQ-S tandem mass spectrometer coupled to Waters Acquity UPLC system (Waters, Hertfordshire, United Kingdom). An Acquity UPLC HSS T3 column (1.8 µm, 2.1 × 100 mm; Waters), with a Security Guard column (C18, 4 × 2.0 mm) from Phenomenex (Torrance, CA), was eluted (0.3 ml/min) with a gradient mobile phase consisting of water and acetonitrile (with 0.1% formic acid). The injection volume was 5 µl (∼10 μg of total protein). The optimized liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry parameters (Prasad et al., 2016) were used in electrospray ionization positive ionization mode. The data were processed by integrating the peak areas generated from the reconstructed ion chromatograms for the analyte peptides and the respective heavy internal standards using the MassLynx software (Waters). The OAT1 protein levels in the cells expressing the OAT1 orthologs from five species were measured; however, the OAT1 protein levels from cells expressing the mutant OAT1 proteins were not determined.

Statistical Analysis.

Unless specified, data in all provided figures and tables are expressed as mean ± S.D. All experiments were performed at least twice with three to four replicates of each data point. Statistical analyses, as specified in the legends of all provided figures and tables, were performed to determine significant differences between controls and treatment groups. The data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 7. A value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Inhibition of OAT1-Mediated 6CF Uptake by ANPs.

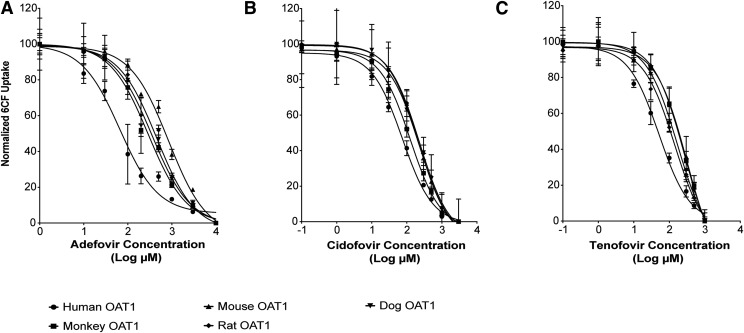

To determine whether there are species differences in the interaction kinetics of ANPs with OAT1, we first characterized the inhibition potencies of the three ANPs. Adefovir, cidofovir, and tenofovir inhibited uptake of 6CF in HEK293 cells stably expressing OAT1 orthologs from five species: hOAT1, cyOAT1, rat OAT1, mouse OAT1, and dog OAT1 (Fig. 1). Notably, the IC50 values of adefovir and tenofovir for hOAT1 (71 ± 15 and 61 ± 14 μM, respectively, Table 1) were significantly lower than the values for OAT1 orthologs from the four preclinical animal species. Importantly, the IC50 values of adefovir, cidofovir, and tenofovir for hOAT1 were 3.1-, 2.1-, and 5.6-fold, respectively, lower than the IC50 values for cyOAT1, which has the greatest homology to hOAT1 compared with the other species orthologs studied.

Fig. 1.

Species differences in the inhibition potencies of ANPs (adefovir, cidofovir, and tenofovir) for OAT1-mediated 6CF uptake. HEK293 cells stably expressing hOAT1, cyOAT1, rat OAT1, mouse OAT1, and dog OAT1 were incubated with HBSS buffer containing 6CF (1 μM) for 1 minute with or without designed concentrations of adefovir, cidofovir, and tenofovir. Data points represent the mean ± S.D. of 6CF uptake from three replicate determinations in a single experiment. The experiments were repeated three times and similar results were obtained. Representative curves of the OAT1-mediated 6CF uptake inhibition by ANPs: (A) Adefovir; (B) Cidofovir; (C) Tenofovir. The IC50 values for each of the analogs with each OAT1 ortholog are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Potencies of ANPs in inhibiting 6CF uptake by OAT1 species orthologs from human, cynomolgus monkey, mouse, rat, and dog

Statistical analyses were performed by one-way analysis of variance followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. N ≥ 2.

| Inhibitor | IC50 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human |

Cynomolgus Monkey |

Mouse |

Rat |

Dog |

|

| μM | μM | μM | μM | μM | |

| Adefovir | 71 ± 15 | 220 ± 67* | 399 ± 147*** | 263 ± 66* | 181 ± 4 |

| Cidofovir | 88 ± 25 | 181 ± 67 | 237 ± 69** | 245 ± 19** | 185 ± 27 |

| Tenofovir | 61 ± 14 | 343 ± 40**** | 165 ± 27* | 153 ± 17 | 223 ± 64** |

P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001.

Kinetic Studies of Tenofovir Transport by hOAT1 and Four Common Preclinical Animals.

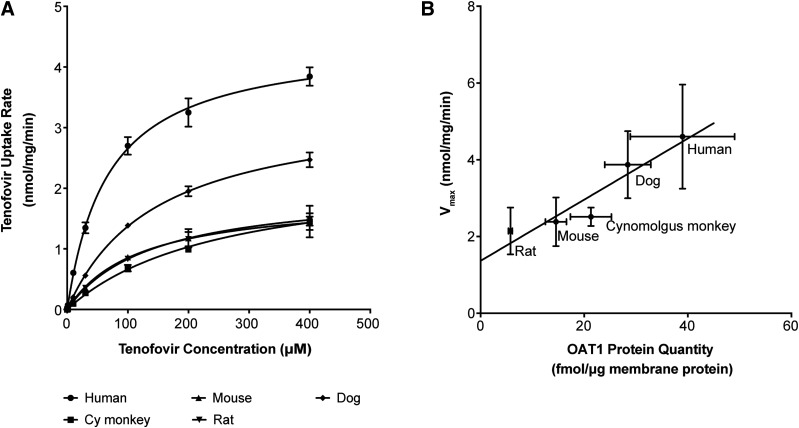

To further characterize species differences in the kinetics of the transporter for ANPs, we used [3H]-tenofovir as a model substrate. We selected tenofovir for more detailed studies because of its widespread use as an antiviral agent; however, key experiments were validated with adefovir and cidofovir (Fig. 3G). First, we compared the kinetics of uptake of [3H]-tenofovir in the stable cell lines recombinantly expressing hOAT1 or the orthologs from the aforementioned four preclinical animals. The Km value for hOAT1-mediated tenofovir uptake (72.6 ± 20 μM) was significantly lower than the respective Km values for OAT1 orthologs from cynomolgus monkey, mouse, rat, and dog (Table 2). Moreover, tenofovir transport efficiency (Vmax/Km) for hOAT1 was greater than its transport efficiency for cyOAT1 before and after normalization for total cell membrane-bound proteins (Fig. 2A; Table 2). As expected, the Vmax value of tenofovir for OAT1 orthologs was significantly correlated with the total cell membrane-associated quantity of OAT1 in the stable cell lines (R2 = 0.89) (Fig. 2B; Supplemental Table 3). It should be noted that membrane-associated protein levels of the various species orthologs of OAT1 in transfected human embryonic kidney cells may not reflect quantities of OAT1 in the kidney tissue. Thus, in vivo maximum transport rates and efficiencies among the OAT1 orthologs may differ from what was observed in the cell lines. In fact, we found that the total cell membrane-bound protein level for hOAT1 was the highest in transfected HEK293 cells but the lowest among all the five species in the kidney cortex (Supplemental Table 3).

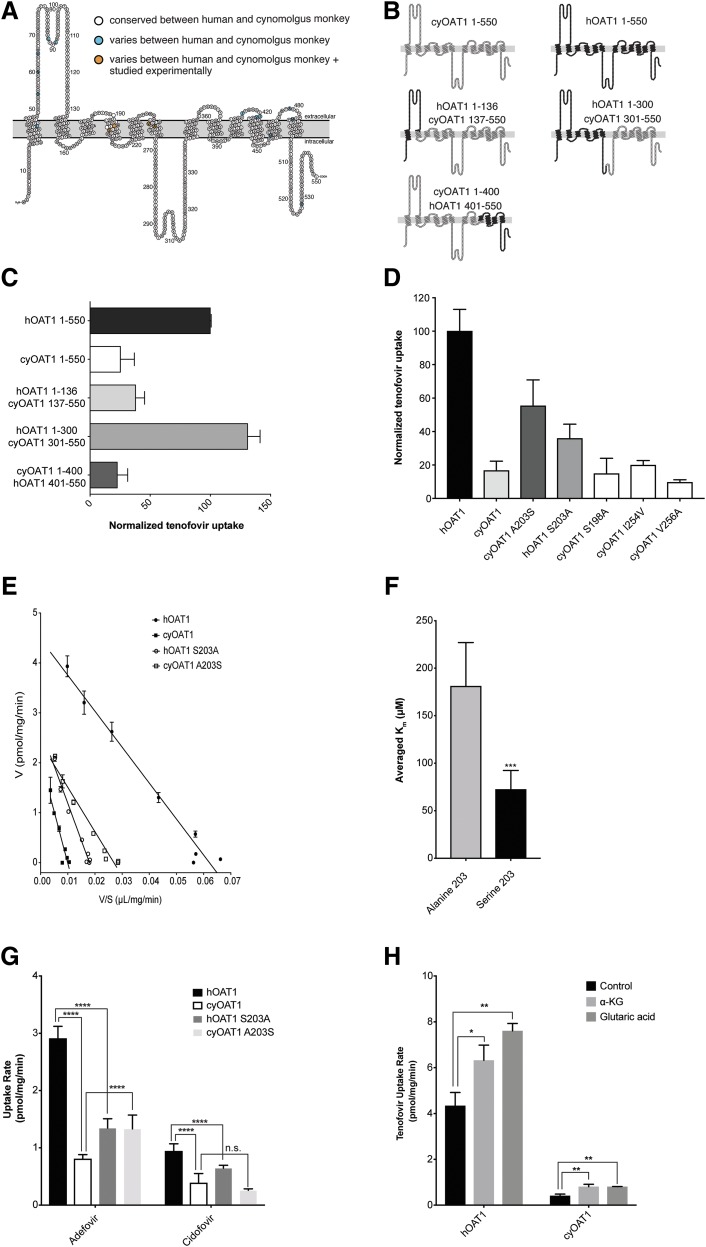

Fig. 3.

Chimera proteins of OAT1 created to assess the critical domains and residues involved in the species differences of tenofovir kinetics in cells stably expressing hOAT1 and cyOAT1. (A) Predicted membrane-bound hOAT1 structure showing 550 amino acids. The white color indicates amino acid residues that are conserved between hOAT1 and cyOAT1, the turquoise color shows residues that vary between hOAT1 and cyOAT1, and the orange color indicates residues that were mutated and evaluated for tenofovir transport kinetics. (B) Wild-type hOAT1, cyOAT1, and chimeric proteins with different combinations of hOAT1 and cyOAT1 amino acids. (C) [3H]-tenofovir uptake by OAT1 chimera proteins. Transiently transfected HEK293 cells overexpressing chimera proteins were incubated with [3H]-tenofovir (50 nM) for 3 minutes. (D) [3H]-tenofovir uptake by cyOAT1 mutants (cyOAT1 S198A, A203S, I254V, and V256A) and hOAT1 mutant (hOAT1 S203A). Transiently transfected HEK293 cells overexpressing mutant proteins were incubated with [3H]-tenofovir (50 nM) for 3 minutes. (E) Eadie-Hofstee plot for the [3H]-tenofovir uptake by stable cell lines overexpressing hOAT1 and cyOAT1 and their mutants, hOAT1 S203A and cyOAT1 A203S. (F) Comparison of the averaged Km values for OAT1 orthologs with S203 (N = 7, including human, chimpanzee, gorilla, orangutan, gibbon, galago, and cynomolgus monkey OAT1 A203S) with that for OAT1 orthologs with alanine at the equivalent position (N = 6, including cynomolgus monkey, squirrel monkey, mouse, rat, dog, and human OAT1 S203A). Student’s t test was performed to determine significant differences between the two groups. (G) The uptake rate of [3H]-adefovir and [3H]-cidofovir in cells overexpressing hOAT1 and cyOAT1 and the mutants, hOAT1 S203A and cyOAT1 A203S. Each column represents the mean ± S.D. uptake in the OAT1-transfected cells minus that in empty vector cells. Two experiments were conducted and there were four replicates for each experiment. Statistical analyses were performed by one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test to determine significant differences between controls and treatment groups. (H) The rate of uptake of [3H]-tenofovir in HEK293 cells overexpressing hOAT1 or cyOAT1 with or without 120-minute preincubation with 5 mM α-ketoglutarate or 5 mM glutaric acid. Each bar represents uptake (mean ± S.D.) in the OAT1-transfected cells minus that in empty vector cells (N ≥ 2). *P value <0.05; **P value < 0.01; ***P value <0.001; ****P value = 0.0001. n.s., not significant.

TABLE 2.

Kinetic parameters of the tenofovir uptake by OAT1 species orthologs from human, cynomolgus monkey, mouse, rat, and dog

Statistical analyses were performed by one-way analysis of variance followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. N ≥ 2; &, tenofovir transport efficiency for OAT1 from each species was normalized to the corresponding membrane-bound OAT1 quantity (Supplemental Table 3).

| Parameter | Human | Cynomolgus Monkey | Mouse | Rat | Dog |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Km (μM) | 72.6 ± 20 | 254 ± 0.1**** | 138 ± 18*** | 139 ± 7.6*** | 157 ± 8.8**** |

| Vmax (nmol/mg/min) | 4.6 ± 1.4 | 2.5 ± 0.2 | 2.4 ± 0.6* | 2.1 ± 0.6* | 3.9 ± 0.9 |

| Vmax/Km (μl/mg/min) | 63 | 10 | 17 | 15 | 25 |

| Normalized Vmax/Km (μl/mg/min)& | 1.62 | 0.47 | 1.17 | 2.59 | 0.88 |

P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001.

Fig. 2.

Kinetics of uptake of tenofovir for species orthologs of OAT1. (A) The uptake kinetics of [3H]-tenofovir in HEK293 cells expressing hOAT1, cyOAT1, rat OAT1, mouse OAT1, and dog OAT1. The uptake rate was evaluated at 3 minutes. Each point represents the mean ± S.D. uptake in the OAT1-transfected cells minus that in empty vector cells. (B) Correlation of the Vmax value of OAT1-mediated tenofovir uptake in HEK293 cells stably expressing five OAT1 species orthologs with total cell membrane-bound OAT1 protein quantity (R2 = 0.892).

Functional Characterization of Chimeric and Mutant Transporters.

cyOAT1 has 96.91% amino acid identity to hOAT1 (Supplemental Table 2) and yet its Km value for tenofovir was 3.5-fold higher than the corresponding Km value for hOAT1 (Table 2). To identify the essential domains and amino acid residues in hOAT1 responsible for the lower Km vaue of tenofovir, chimeric transporters between cyOAT1 and hOAT1 were created and characterized. Tenofovir uptake for chimeric transporter hOAT1 1–300 + cyOAT1 301–550 was comparable to that for hOAT1 wild type. In contrast, hOAT1 1–136 + cyOAT1 137–550 and cyOAT1 1–400 + hOAT1 401–550 were comparable to cyOAT1 wild type (Fig. 3C). These results suggested that the residues critical for the greater transport efficiency and lower Km values of tenofovir were in hOAT1 residues 136–300. Therefore, we focused on four hOAT1 residues, which differ between hOAT1 and cyOAT1 in this region, A198, S203, V254, and A256 (Fig. 3A).

Expression vectors containing cyOAT1 with each of the four amino acids mutated to the corresponding amino acid in hOAT1 (S198A, A203S, I254V, and V256A) were constructed and transiently overexpressed in HEK293 cells. The tenofovir uptake rate for cyOAT1 A203S was almost three times greater than that of wild-type cyOAT1 (Fig. 3D), whereas no significant changes in its uptake rate were observed for the other three mutants. Next, we evaluated tenofovir transport in cells expressing the corresponding mutation in hOAT1 (S203A), which resulted in a 60% reduction in the rate of tenofovir uptake (Fig. 3D). In addition, the Km value of tenofovir for hOAT1 S203A (216 ± 19 μM) was significantly higher than for hOAT1 wild type (72 ± 20 µM), whereas the Km value of tenofovir for cyOAT1 A203S (105 ± 27 μM) was significantly lower than for cyOAT1 wild type (254 ± 0.1 µM). Furthermore, the Km value of tenofovir for cyOAT1 A203S was not significantly different from hOAT1 wild type (Fig. 3E; Table 3). These experimental results were further supported by the docking results of tenofovir against a hOAT1 comparative structure model. The –PO3H2 moiety is shown to form a hydrogen bond with the side chain hydroxyl of S203 and Y230, thus stabilizing tenofovir within the binding site (Supplemental Fig. 1) and S203A mutation eliminates this favorable interaction. These results strongly suggest that S203 in hOAT1 is important for the lower Km value of tenofovir. Notably, the uptake rates of [3H]-adefovir and [3H]-cidofovir for hOAT1 were significantly greater than those for cyOAT1 and hOAT1 S203A (P = 0.0001). Consistently, the uptake rate of [3H]-adefovir for cyOAT1 A203S was significantly higher than that for cyOAT1 (P = 0.0001). In contrast, the uptake rate of [3H]-cidofovir for cyOAT1 A203S was not significantly higher than that for cyOAT1 (Fig. 3G). In addition, since OAT1 functions as a substrate/α-ketoglutarate exchanger (Lu et al., 1999), we measured hOAT1- and cyOAT1-mediated [3H]-tenofovir uptake after preincubation with 5 mM α-ketoglutarate or glutaric acid for 120 minutes. Consistent with the previous study (Lu et al., 1999), pretreatment with α-ketoglutarate and glutaric acid significantly increased [3H]-tenofovir uptake by both hOAT1 and cyOAT1 (Fig. 3H). α-Ketoglutarate preincubation had a greater effect on tenofovir uptake by cyOAT1 than by hOAT1 (1.45 times vs. 1.95 times tenofovir uptake in the absence of α-ketoglutarate in cells expressing hOAT1 and cyOAT1, respectively). However, cyOAT1 transport activity remained significantly lower than hOAT1 transport activity after preincubation with α-ketoglutarate. These results suggest that α-ketoglutarate and glutaric acid stimulate the activity of OAT1 irrespective of whether an alanine or a serine is present at position 203. Additionally, an alanine at position 203 results in lower activity of OAT1 in comparison with a serine at the same position in the presence or absence of the counterion.

TABLE 3.

Kinetic parameters for OAT1-mediated uptake by wild-type and mutant transporters

Mutations were created by site-directed mutagenesis of both hOAT1 and cyOAT1 at position 203. Statistical analyses were performed by one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. N ≥ 2; * represents comparison with human; # represents comparison between cynomolgus monkey and cynomolgus monkey A203S.

| Parameter | Human | Cynomolgus Monkey | Cynomolgus Monkey A203S | Human S203A |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Km (μM) | 72.6 ± 20 | 254 ± 0.1**** | 105 ± 27### | 216 ± 19*** |

| Vmax (nmol/mg/min) | 4.6 ± 1.4 | 2.5 ± 0.2 | 2.8 ± 0.1 | 3.6 ± 0.7 |

| Vmax/Km (μl/mg/min) | 63 | 10 | 27 | 17 |

P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001; ###P < 0.001.

Comparison of Km Values of Tenofovir for OAT1 Orthologs with Serine or Alanine.

Tenofovir uptake kinetics in stable cell lines recombinantly expressing OAT1 orthologs from chimpanzee, gorilla, orangutan, gibbon, squirrel monkey, and galago were determined to confirm the critical role of S203 in hOAT1-mediated tenofovir uptake. The mean value of Km (72.4 ± 20 μM) for seven OAT1 proteins with serine was significantly lower (P < 0.001) than the respective value for six OAT1 proteins with an alanine at the equivalent position (181 ± 46 μM) (Fig. 3F; Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Kinetic parameters of tenofovir uptake rate by OAT1 wild-type transporters and mutants at position 203

| Species | Amino Acid at position 203 or Equivalent Position |

Km |

|---|---|---|

| μM | ||

| Human | S | 72.6 ± 20 |

| Chimpanzee | S | 44.2 ± 1.5 |

| Gorilla | S | 56.0 ± 7.5 |

| Orangutan | S | 79.0 ± 16 |

| Gibbon | S | 65.0 ± 2.4 |

| Galago | S | 84.9 ± 24 |

| cyOAT1 A203S | S | 105 ± 27 |

| Cynomolgus monkey | A | 254 ± 0.1 |

| Squirrel monkey | A | 181 ± 60 |

| Mouse | A | 138 ± 18 |

| Rat | A | 139 ± 7.6 |

| Dog | A | 157 ± 8.8 |

| hOAT1 S203A | A | 216 ± 19 |

S, Serine; A, Alanine.

Association of OAT1-Mediated Tenofovir Transport Efficiency (Vmax/Km) with Serum Uric Acid Levels.

Evolutionary studies reveal that uricase was lost during primate evolution (Kratzer et al., 2014) and consequently apes have significantly elevated SUA levels (Table 5). We observed that the mean value of OAT1-mediated tenofovir transport efficiency (Vmax/Km) was significantly greater in apes (58.9 ± 8.3 μl/mg/min, N = 5) in comparison with species with much lower SUA levels (16.5 ± 5.3 μl/mg/min, N = 5, P < 0.0001) (Fig. 4A; Table 5). Intriguingly, all apes (human, chimpanzee, gorilla, orangutan, and gibbon) have a S203 (Table 4). In contrast, alanine is the only amino acid at the equivalent position in 12 OAT1 orthologs from Old World monkeys (Supplemental Table 4), which are the most closely related primates to apes. In addition, alanine is the dominant amino acid at the equivalent position in four OAT1 orthologs from New World monkeys. Importantly, Cebus capucinus, unlike the other three New World monkeys, maintains high SUA levels similar to human and has a T203 (Fanelli and Beyer, 1974). The [3H]-Tenofovir uptake rate in transiently transfected human embryonic kidney cells overexpressing hOAT1 S203T was 75% of hOAT1 wild type and 4.2 times that of cyOAT1 wild type (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, the Km value of uric acid for hOAT1 (571 ± 97.7 μM) was significantly lower than its Km value for cyOAT1 (1070 ± 90 μM) (Fig. 5; Table 6). The differences in Km values of ANPs between cyOAT1 and hOAT1 were much greater than the 2-fold difference in Km values for uric acid in the two species. Nevertheless, the data suggest a potentially important endogenous role of S203 in apes.

TABLE 5.

OAT1-mediated tenofovir transport efficiencies and SUA levels in species with or without functional uricase

*The mean value of SUA was calculated based on reported levels. The range of SUA is included in parenthesis. —, not applicable.

| Species | Without Uricase Activity |

With Uricase Activity |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SUA* |

Tenofovir Transport Efficiency |

SUA |

Tenofovir Transport Efficiency |

|

| μM | μl/mg/min | μM | μl/mg/min | |

| Human | 318 (210–420) (Tan et al., 2016) | 63 | — | — |

| Chimpanzee | 244 (120–360) (Fanelli and Beyer, 1974) | 61 | — | — |

| Gorilla | 146 (130–160) (Fanelli and Beyer, 1974) | 49 | — | — |

| Orangutan | 140 (110–170) (Fanelli and Beyer, 1974) | 69 | — | — |

| Gibbon | 178 (120–300) (Fanelli and Beyer, 1974) | 52 | — | — |

| Cynomolgus monkey | — | — | 36 (30–42) (Fanelli and Beyer, 1974) | 10 |

| Squirrel monkey | — | — | 30 (12–60) (Fanelli and Beyer, 1974) | 15 |

| Mouse | — | — | 53 (30–78) (Wu et al., 1994; So and Thorens, 2010) | 17 |

| Rat | — | — | 67 (64–70) (Mazzali et al., 2001; Lu et al., 2016) | 15 |

| Dog | — | — | 18 (Miller et al., 1951) | 25 |

| Mean | 205 ± 75 | 58.9 ± 8.3 | 41 ± 19 | 16.5 ± 5.3 |

Fig. 4.

Association of OAT1-mediated tenofovir transport efficiency (Vmax/Km) with SUA levels and effect of amino acid substitutions in hOAT1 on tenofovir uptake rate. (A) Mean ± S.D. of SUA levels (black bar) and OAT1-mediated tenofovir transport efficiencies (gray bar) in species with (cynomolgus monkey, squirrel monkey, mouse, rat, and dog) and without (human, chimpanzee, gorilla, orangutan, and gibbon) functional uricase (* represents comparison of SUA levels in species with and without uricase; # represents comparison of tenofovir transport efficiencies in species with and without uricase; **P < 0.01; ####P < 0.0001). (B) [3H]-tenofovir uptake by hOAT1, cyOAT1, and mutants (hOAT1 S203T and hOAT1 S203A). Transiently transfected HEK293 cells overexpressing wild-type or mutant proteins were incubated with [3H]-tenofovir (50 nM) for 3 minutes. Transporter-mediated tenofovir uptake was obtained after subtracting the respective rate of uptake in empty vector cells.

Fig. 5.

Uric acid uptake in HEK293 cells expressing hOAT1 or cyOAT1 as a function of time and concentration. (A) Uptake of [14C]-uric acid (20 μM) as a function of time in cells expressing hOAT1 and in empty vector cells. (B) Kinetics of [14C]-uric acid uptake by hOAT1 and cyOAT1. HEK293 cells overexpressing hOAT1 and cyOAT1 were incubated with [14C]-uric acid (20 μM) with various concentrations of unlabeled uric acid for 5 minutes. Stock of uric acid was dissolved in 0.1 N NaOH and added to obtain designed concentrations in HBSS buffer plus 10 mM HEPES to maintain pH 7.4. Each point represents the uptake in OAT1-expressing cells minus that in empty vector cells.

TABLE 6.

Kinetic parameters of [14C]-uric acid uptake by hOAT1 and cyOAT1 in HEK293 cells stably expressing the transporters

Student’s t test was performed to determine significant differences between the two groups. N ≥ 2.

| Parameter | Human | Cynomolgus Monkey |

|---|---|---|

| Km (μM) | 571 ± 97.7 | 1070 ± 90** |

| Vmax (pmol/mg/min) | 1510 ± 243 | 1040 ± 106 |

| Vmax/Km (μl/mg/min) | 2.6 | 0.97 |

P < 0.01.

Discussion

Nephrotoxicity is a particular concern for many antiviral agents (De Clercq and Holý, 2005; Izzedine et al., 2005). To ensure the safety of healthy volunteers in first-in-human clinical studies, estimation of the maximum safe starting dose is essential, and the most widely used method is based on no observable adverse effect levels in multiple preclinical animal species (Zou et al., 2012). Transporters in the solute carrier superfamily are important determinants of tissue levels and subcellular distribution of many drugs (Leabman et al., 2003; Giacomini et al., 2010; Shima et al., 2010; Dahlin et al., 2013; Yee et al., 2013), and therefore play a role in drug toxicities. Thus, species differences in the activity or expression of solute carrier transporters may lead to failure to adequately predict drug toxicities in humans. For example, differences in subcellular expression levels of equilibrative nucleoside transporter 1 between rodents and humans led to the failure to predict the mitochondrial toxicity of fialuridine in humans that resulted in several deaths and withdrawal of the drug in phase I clinical trials (McKenzie et al., 1995; Lee et al., 2006). In this study, we focused on OAT1 because OAT1 expression greatly enhances the cytotoxicity of ANPs (Ho et al., 2000). In addition, the apparent failure to adequately predict the pronounced nephrotoxicity of adefovir (at 120 mg) in humans from preclinical studies in animal species (Benhamou et al., 2001) motivated us further to explore species difference in OAT1.

The major finding of this study was that there are large species differences in the uptake of ANPs via OAT1 (Table1). Notably, tenofovir had a significantly lower Km value for hOAT1 than for OAT1 orthologs from cynomolgus monkey, mouse, rat, and dog (Table 2). Furthermore, substitution of S203 for alanine in cyOAT1 resulted in a significantly greater tenofovir transport rate (Table 3). These data suggest that hOAT1 transport may mediate a greater accumulation of ANPs in human proximal tubule in comparison with OAT1 orthologs from preclinical animal species. The high correlation between the Vmax value and total cell membrane-bound protein quantity among the five species (Fig. 2B; Supplemental Table 3) suggests that the turnover rate for tenofovir by OAT1 orthologs from the five species was similar.

There have been many studies examining the molecular basis of OAT1 function, and identifying critical amino acid residues and domains of the protein responsible for substrate recognition and translocation (Tanaka et al., 2004; You, 2004; Perry et al., 2006; Xu et al., 2006; Hong et al., 2007a,b; Rizwan et al., 2007; Keller et al., 2011). Importantly, we report that S203 in hOAT1 is a key determinant of the lower Km value of tenofovir. Notably, compared with all of the amino acid residues in hOAT1 previously reported to be involved in the transport of ANPs—R50 (Bleasby et al., 2005), Y230 (Perry et al., 2006), and F438 (Perry et al., 2006)—S203 is the only amino acid that is different between hOAT1 and the orthologs from cynomolgus monkey, mouse, rat, and dog. It is worth noting that there was no significant species difference in the Km value for the canonical substrate of OAT1, p-aminohippuric acid, between hOAT1 and cyOAT1 (Supplemental Fig. 2; Supplemental Table 5), suggesting that species differences in OAT1 orthologs are substrate dependent. These results have implications for drug development since they suggest that allometric scaling may be used to predict renal accumulation of some OAT1 substrates (e.g., p-aminohippuric acid), but not others (e.g., tenofovir).

The maximal plasma concentrations for tenofovir in both humans (range 0.72–1.0 µM, oral dose of 300 mg) and rhesus macaques (range 1.28–2.3 µM, oral dose of 30 mg) (Kearney et al., 2004; Best et al., 2015) are well below their respective Km values (Table 2). Thus, OAT1-mediated tenofovir transport into proximal tubule cells of both humans and monkeys will be inversely correlated with their respective Km values (Table 2). Although the plasma concentrations of tenofovir are somewhat lower in humans than in monkeys at therapeutic doses, a greater accumulation of tenofovir in human proximal tubule cells may be predicted based on the lower Km value of tenofovir for hOAT1 (Table 2).

Although OAT1 transports tenofovir into the proximal tubule cell across the basolateral membrane, multidrug resistance protein type 4 transports the drug from the cell into the lumen during active tubular secretion (Ray et al., 2006). In fact, cells expressing multidrug resistance protein type 4 are 2- to 2.5-fold less susceptible to tenofovir-induced cytotoxicity. In addition, to become pharmacologically active or cytotoxic, tenofovir requires phosphorylation by intracellular nucleotide kinases (Ho et al., 2000; Lade et al., 2015). Thus, multidrug resistance protein type 4 and nucleotide kinases, in addition to OAT1, may directly affect levels of tenofovir and other ANPs in the proximal tubule, and modulate renal toxicity.

Of particular interest is that S203 is conserved in all of the apes sequenced and archived in the National Center for Biotechnology Information database and UCSC Genome Browser to date (as of when this paper was submitted), including human, chimpanzee, pygmy chimpanzee, gorilla, orangutan, and gibbon (Supplemental Table 4). In contrast, most primates and more distant species from humans have an alanine at the equivalent position. Apes lost functional uricase during evolution (Kratzer et al., 2014) and subsequently SUA levels increased 2–17 times (Table 5). Uricase is responsible for the hydrolysis of uric acid to the more water-soluble product, allantoin, in the purine degradation pathway (Motojima et al., 1988). Mammals possessing a functional uricase typically have low SUA levels. It should be noted that 70% of daily uric acid disposal occurs via the kidneys and its excretion and reabsorption are regulated by several renal transporters (Vitart et al., 2008; So and Thorens, 2010). Polymorphisms in genes encoding these transporters, such as SLC22A12, SLC2A9, and ABCG2, are associated with high SUA levels and gout (Graessler et al., 2006; Vitart et al., 2008; Kolz et al., 2009; Woodward et al., 2009). It was not previously known that the SLC22A6 locus is associated with SUA levels or gout in genome-wide association studies. However, a recent genome-wide association study in 109,029 Japanese populations (Kanai et al., 2018) showed that single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) within the SLC22A6 locus are significantly associated with SUA levels with the top SNP (rs148838714) at a P value of 3.5 × 10−34 (see Supplemental Fig. 4; Supplemental Table 6). Although the function of the SNPs within this locus is not currently known, some of these SNPs within the locus are more common in Japanese populations. Future studies are needed to characterize the function of these variants, and perhaps through sequencing analysis to identify the causative variant that affects SUA. Our kinetic data showing that uric acid has a lower Km value for hOAT1 than for cyOAT1 (Fig. 5; Table 6) show similar trends as in the kinetic data for URAT1 and suggest that OAT1 with S203 potentially evolved to more efficiently transport uric acid in apes. We also note that threonine at position 203, which is present in OAT1 from Cebus capucinus imitator, an Old World monkey that maintains high SUA levels (Fanelli and Beyer, 1974), results in similar transport efficiency as serine at the equivalent position (Fig. 4B). Thus, either a serine or a threonine may suffice at position 203 to confer greater OAT1 transport efficiency. The data are consistent with the evolution of alanine to serine or threonine in OAT1 to accommodate high levels of uric acid.

In conclusion, our study indicates that there are large species differences in the kinetics of interaction of OAT1 for ANPs. S203 contributes to the lower Km value of tenofovir and uric acid for hOAT1, suggesting a novel molecular mechanism underlying species difference in the kinetics of interaction of OAT1 with ANPs. Furthermore, S203 is conserved in apes with loss of uricase and subsequent elevated SUA levels, suggesting a potentially important role in uric acid excretion and in primate evolution. Finally, our results suggest that typical species used in preclinical toxicology studies may not recapitulate OAT1-mediated drug accumulation in the kidney, resulting in poor ability to predict nephrotoxicity for drugs that are substrates of OAT1.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. John Witte and Dr. Sara Rashkin at University of California, San Francisco, for the consultation on statistical analysis.

Abbreviations

- ANP

acyclic nucleoside phosphonate

- A203

alanine at position 203

- 6CF

6-carboxyfluorescein

- cyOAT1

cynomolgus monkey organic anion transporter 1

- HBSS

Hanks’ balanced salt solution

- HEK293

human embryonic kidney 293

- hOAT1

human organic anion transporter 1

- OAT1

organic anion transporter 1

- SNP

single-nucleotide polymorphism

- S203

serine at position 203

- SUA

serum uric acid

Authorship Contributions

Participated in research design: Zou, Stecula, Gupta, Stahl, Fenner, Giacomini.

Conducted experiments: Zou, Stecula, Prasad, Chien, Wang.

Contributed new reagents or analytic tools: Unadkat.

Performed data analysis: Zou, Stecula, Gupta, Prasad, Yee, Giacomini.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Zou, Stecula, Gupta, Prasad, Unadkat, Stahl, Fenner, Giacomini.

Footnotes

Funding for this project was provided by AstraZeneca UK Ltd. and the National Institutes of Health [Grant R01-DK103729] (to K.M.G.).

This article has supplemental material available at molpharm.aspetjournals.org.

This article has supplemental material available at molpharm.aspetjournals.org.

References

- Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schäffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. (1997) Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res 25:3389–3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benhamou Y, Bochet M, Thibault V, Calvez V, Fievet MH, Vig P, Gibbs CS, Brosgart C, Fry J, Namini H, et al. (2001) Safety and efficacy of adefovir dipivoxil in patients co-infected with HIV-1 and lamivudine-resistant hepatitis B virus: an open-label pilot study. Lancet 358:718–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Best BM, Burchett S, Li H, Stek A, Hu C, Wang J, Hawkins E, Byroads M, Watts DH, Smith E, et al. International Maternal Pediatric and Adolescent AIDS Clinical Trials (IMPAACT) P1026s Team (2015) Pharmacokinetics of tenofovir during pregnancy and postpartum. HIV Med 16:502–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleasby K, Hall LA, Perry JL, Mohrenweiser HW, Pritchard JB. (2005) Functional consequences of single nucleotide polymorphisms in the human organic anion transporter hOAT1 (SLC22A6). J Pharmacol Exp Ther 314:923–931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cihlar T, Lin DC, Pritchard JB, Fuller MD, Mendel DB, Sweet DH. (1999) The antiviral nucleotide analogs cidofovir and adefovir are novel substrates for human and rat renal organic anion transporter 1. Mol Pharmacol 56:570–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman RG, Carchia M, Sterling T, Irwin JJ, Shoichet BK. (2013) Ligand pose and orientational sampling in molecular docking. PLoS One 8:e75992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlin A, Geier E, Stocker SL, Cropp CD, Grigorenko E, Bloomer M, Siegenthaler J, Xu L, Basile AS, Tang-Liu DD, et al. (2013) Gene expression profiling of transporters in the solute carrier and ATP-binding cassette superfamilies in human eye substructures. Mol Pharm 10:650–663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlin A, Wittwer M, de la Cruz M, Woo JM, Bam R, Scharen-Guivel V, Flaherty J, Ray AS, Cihlar T, Gupta SK, et al. (2015) A pharmacogenetic candidate gene study of tenofovir-associated Fanconi syndrome. Pharmacogenet Genomics 25:82–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Clercq E, Holý A. (2005) Acyclic nucleoside phosphonates: a key class of antiviral drugs. Nat Rev Drug Discov 4:928–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar RC. (2004) MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res 32:1792–1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanelli GM, Beyer KH. (1974) Uric acid in nonhuman primates with special reference to its renal transport. Annu Rev Pharmacol 14:355–364. [Google Scholar]

- Fujita T, Brown C, Carlson EJ, Taylor T, de la Cruz M, Johns SJ, Stryke D, Kawamoto M, Fujita K, Castro R, et al. (2005) Functional analysis of polymorphisms in the organic anion transporter, SLC22A6 (OAT1). Pharmacogenet Genomics 15:201–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giacomini KM, Huang SM, Tweedie DJ, Benet LZ, Brouwer KL, Chu X, Dahlin A, Evers R, Fischer V, Hillgren KM, et al. International Transporter Consortium (2010) Membrane transporters in drug development. Nat Rev Drug Discov 9:215–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goujon M, McWilliam H, Li W, Valentin F, Squizzato S, Paern J, Lopez R. (2010) A new bioinformatics analysis tools framework at EMBL-EBI. Nucleic Acids Res 38:W695–W699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graessler J, Graessler A, Unger S, Kopprasch S, Tausche AK, Kuhlisch E, Schroeder HE. (2006) Association of the human urate transporter 1 (hURAT1) with reduced renal uric acid excretion and hyperuricemia in a German Caucasian population. Arthritis Rheum 54:290–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho ES, Lin DC, Mendel DB, Cihlar T. (2000) Cytotoxicity of antiviral nucleotides adefovir and cidofovir is induced by the expression of human renal organic anion transporter 1. J Am Soc Nephrol 11:383–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong M, Tanaka K, Pan Z, Ma J, You G. (2007a) Determination of the external loops and the cellular orientation of the N- and the C-termini of the human organic anion transporter hOAT1. Biochem J 401:515–520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong M, Zhou F, Lee K, You G. (2007b) The putative transmembrane segment 7 of human organic anion transporter hOAT1 dictates transporter substrate binding and stability. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 320:1209–1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izzedine H, Launay-Vacher V, Deray G. (2005) Antiviral drug-induced nephrotoxicity. Am J Kidney Dis 45:804–817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanai M, Akiyama M, Takahashi A, Matoba N, Momozawa Y, Ikeda M, Iwata N, Ikegawa S, Hirata M, Matsuda K, et al. (2018) Genetic analysis of quantitative traits in the Japanese population links cell types to complex human diseases. Nat Genet 50:390–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearney BP, Flaherty JF, Shah J. (2004) Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate: clinical pharmacology and pharmacokinetics. Clin Pharmacokinet 43:595–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller T, Egenberger B, Gorboulev V, Bernhard F, Uzelac Z, Gorbunov D, Wirth C, Koppatz S, Dötsch V, Hunte C, et al. (2011) The large extracellular loop of organic cation transporter 1 influences substrate affinity and is pivotal for oligomerization. J Biol Chem 286:37874–37886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolz M, Johnson T, Sanna S, Teumer A, Vitart V, Perola M, Mangino M, Albrecht E, Wallace C, Farrall M, et al. EUROSPAN Consortium. ENGAGE Consortium. PROCARDIS Consortium. KORA Study. WTCCC (2009) Meta-analysis of 28,141 individuals identifies common variants within five new loci that influence uric acid concentrations. PLoS Genet 5:e1000504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozakov D, Grove LE, Hall DR, Bohnuud T, Mottarella SE, Luo L, Xia B, Beglov D, Vajda S. (2015) The FTMap family of web servers for determining and characterizing ligand-binding hot spots of proteins. Nat Protoc 10:733–755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kratzer JT, Lanaspa MA, Murphy MN, Cicerchi C, Graves CL, Tipton PA, Ortlund EA, Johnson RJ, Gaucher EA. (2014) Evolutionary history and metabolic insights of ancient mammalian uricases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111:3763–3768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacy SA, Hitchcock MJ, Lee WA, Tellier P, Cundy KC. (1998) Effect of oral probenecid coadministration on the chronic toxicity and pharmacokinetics of intravenous cidofovir in cynomolgus monkeys. Toxicol Sci 44:97–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lade JM, To EE, Hendrix CW, Bumpus NN. (2015) Discovery of genetic variants of the kinases that activate tenofovir in a compartment-specific manner. EBioMedicine 2:1145–1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leabman MK, Huang CC, DeYoung J, Carlson EJ, Taylor TR, de la Cruz M, Johns SJ, Stryke D, Kawamoto M, Urban TJ, et al. Pharmacogenetics Of Membrane Transporters Investigators (2003) Natural variation in human membrane transporter genes reveals evolutionary and functional constraints. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100:5896–5901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee EW, Lai Y, Zhang H, Unadkat JD. (2006) Identification of the mitochondrial targeting signal of the human equilibrative nucleoside transporter 1 (hENT1): implications for interspecies differences in mitochondrial toxicity of fialuridine. J Biol Chem 281:16700–16706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang X, Chien HC, Yee SW, Giacomini MM, Chen EC, Piao M, Hao J, Twelves J, Lepist EI, Ray AS, et al. (2015) Metformin is a substrate and inhibitor of the human thiamine transporter, THTR-2 (SLC19A3). Mol Pharm 12:4301–4310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu JJ, Jia BJ, Yang L, Zhang W, Dong X, Li P, Chen J. (2016) Ultra-high performance liquid chromatography with ultraviolet and tandem mass spectrometry for simultaneous determination of metabolites in purine pathway of rat plasma. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci 1036–1037:84–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu R, Chan BS, Schuster VL. (1999) Cloning of the human kidney PAH transporter: narrow substrate specificity and regulation by protein kinase C. Am J Physiol 276:F295–F303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzali M, Hughes J, Kim YG, Jefferson JA, Kang DH, Gordon KL, Lan HY, Kivlighn S, Johnson RJ. (2001) Elevated uric acid increases blood pressure in the rat by a novel crystal-independent mechanism. Hypertension 38:1101–1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie R, Fried MW, Sallie R, Conjeevaram H, Di Bisceglie AM, Park Y, Savarese B, Kleiner D, Tsokos M, Luciano C, et al. (1995) Hepatic failure and lactic acidosis due to fialuridine (FIAU), an investigational nucleoside analogue for chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med 333:1099–1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McWilliam H, Li W, Uludag M, Squizzato S, Park YM, Buso N, Cowley AP, Lopez R. (2013) Analysis tool web services from the EMBL-EBI. Nucleic Acids Res 41:W597–W600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellors JW. (1999) Adefovir for the treatment of HIV infection: if not now, when? JAMA 282:2355–2356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller GE, Danzig LS, Talbott JH. (1951) Urinary excretion of uric acid in the Dalmatian and non-Dalmatian dog following administration of diodrast, sodium salicylate and a mercurial diuretic. Am J Physiol 164:155–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motojima K, Kanaya S, Goto S. (1988) Cloning and sequence analysis of cDNA for rat liver uricase. J Biol Chem 263:16677–16681. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen BP, Kumar H, Waight AB, Risenmay AJ, Roe-Zurz Z, Chau BH, Schlessinger A, Bonomi M, Harries W, Sali A, et al. (2013) Crystal structure of a eukaryotic phosphate transporter. Nature 496:533–536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei J, Tang M, Grishin NV. (2008) PROMALS3D web server for accurate multiple protein sequence and structure alignments. Nucleic Acids Res 36:W30–W34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry JL, Dembla-Rajpal N, Hall LA, Pritchard JB. (2006) A three-dimensional model of human organic anion transporter 1: aromatic amino acids required for substrate transport. J Biol Chem 281:38071–38079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad B, Johnson K, Billington S, Lee C, Chung GW, Brown CD, Kelly EJ, Himmelfarb J, Unadkat JD. (2016) Abundance of drug transporters in the human kidney cortex as quantified by quantitative targeted proteomics. Drug Metab Dispos 44:1920–1924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray AS, Cihlar T, Robinson KL, Tong L, Vela JE, Fuller MD, Wieman LM, Eisenberg EJ, Rhodes GR. (2006) Mechanism of active renal tubular efflux of tenofovir. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 50:3297–3304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizwan AN, Krick W, Burckhardt G. (2007) The chloride dependence of the human organic anion transporter 1 (hOAT1) is blunted by mutation of a single amino acid. J Biol Chem 282:13402–13409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sali A, Blundell TL. (1993) Comparative protein modelling by satisfaction of spatial restraints. J Mol Biol 234:779–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen MY, Sali A. (2006) Statistical potential for assessment and prediction of protein structures. Protein Sci 15:2507–2524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shima JE, Komori T, Taylor TR, Stryke D, Kawamoto M, Johns SJ, Carlson EJ, Ferrin TE, Giacomini KM. (2010) Genetic variants of human organic anion transporter 4 demonstrate altered transport of endogenous substrates. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 299:F767–F775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sievers F, Wilm A, Dineen D, Gibson TJ, Karplus K, Li W, Lopez R, McWilliam H, Remmert M, Söding J, et al. (2011) Fast, scalable generation of high-quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega. Mol Syst Biol 7:539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- So A, Thorens B. (2010) Uric acid transport and disease. J Clin Invest 120:1791–1799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tahara H, Shono M, Kusuhara H, Kinoshita H, Fuse E, Takadate A, Otagiri M, Sugiyama Y. (2005) Molecular cloning and functional analyses of OAT1 and OAT3 from cynomolgus monkey kidney. Pharm Res 22:647–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan PK, Farrar JE, Gaucher EA, Miner JN. (2016) Coevolution of URAT1 and uricase during primate evolution: implications for serum urate homeostasis and gout. Mol Biol Evol 33:2193–2200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka K, Zhou F, Kuze K, You G. (2004) Cysteine residues in the organic anion transporter mOAT1. Biochem J 380:283–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uwai Y, Ida H, Tsuji Y, Katsura T, Inui K. (2007) Renal transport of adefovir, cidofovir, and tenofovir by SLC22A family members (hOAT1, hOAT3, and hOCT2). Pharm Res 24:811–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitart V, Rudan I, Hayward C, Gray NK, Floyd J, Palmer CN, Knott SA, Kolcic I, Polasek O, Graessler J, et al. (2008) SLC2A9 is a newly identified urate transporter influencing serum urate concentration, urate excretion and gout. Nat Genet 40:437–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodward OM, Köttgen A, Coresh J, Boerwinkle E, Guggino WB, Köttgen M. (2009) Identification of a urate transporter, ABCG2, with a common functional polymorphism causing gout. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106:10338–10342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X, Wakamiya M, Vaishnav S, Geske R, Montgomery C, Jr, Jones P, Bradley A, Caskey CT. (1994) Hyperuricemia and urate nephropathy in urate oxidase-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91:742–746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W, Tanaka K, Sun AQ, You G. (2006) Functional role of the C terminus of human organic anion transporter hOAT1. J Biol Chem 281:31178–31183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yee SW, Nguyen AN, Brown C, Savic RM, Zhang Y, Castro RA, Cropp CD, Choi JH, Singh D, Tahara H, et al. (2013) Reduced renal clearance of cefotaxime in asians with a low-frequency polymorphism of OAT3 (SLC22A8). J Pharm Sci 102:3451–3457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- You G. (2004) Towards an understanding of organic anion transporters: structure-function relationships. Med Res Rev 24:762–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou P, Yu Y, Zheng N, Yang Y, Paholak HJ, Yu LX, Sun D. (2012) Applications of human pharmacokinetic prediction in first-in-human dose estimation. AAPS J 14:262–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]