Abstract

Objectives

Given that many adolescent e-cigarette users are never-smokers, the possibility that e-cigarettes may act as a gateway to future cigarette smoking has been discussed in various studies. Longitudinal data are needed to explore the pathway between e-cigarette and cigarette use, particularly among different risk groups including susceptible and non-susceptible never-smokers. The objective of this study was to examine whether baseline use of e-cigarettes among a sample of never-smoking youth predicted cigarette smoking initiation over a 2-year period.

Design

Longitudinal cohort study.

Setting

89 high schools across Ontario and Alberta, Canada.

Participants

A sample of grade 9–11 never-smoking students at baseline (n=9501) who participated in the COMPASS study over 2 years.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Participants completed in-class questionnaires that assessed smoking susceptibility and smoking initiation.

Results

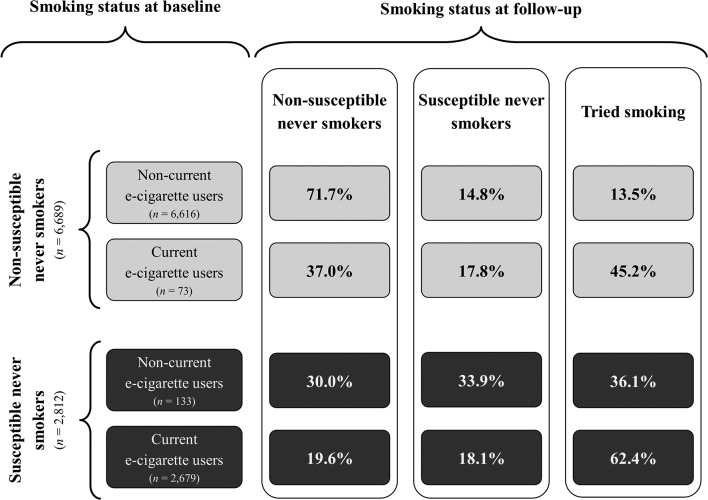

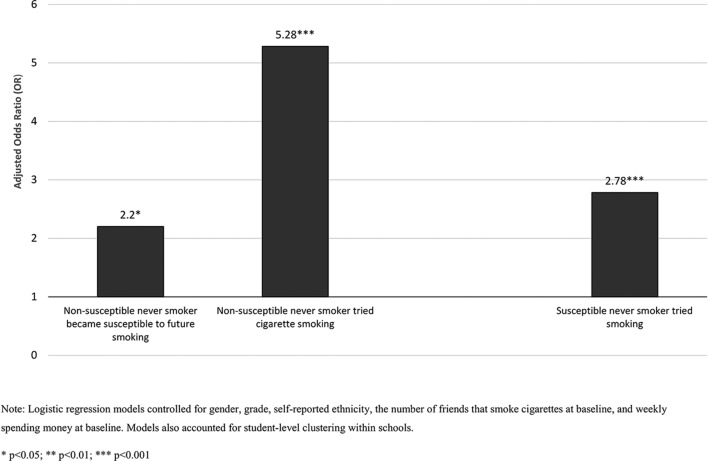

Among the baseline sample of non-susceptible never-smokers, 45.2% of current e-cigarette users reported trying a cigarette after 2 years compared with 13.5% of non-current e-cigarette users. Among the baseline sample of susceptible never-smokers, 62.4% of current e-cigarette users reported trying a cigarette after 2 years compared with 36.1% of non-current e-cigarette users. Overall, current e-cigarette users were more likely to try a cigarette 2 years later. This association was stronger among the sample of non-susceptible never-smokers (AOR=5.28, 95% CI 2.81 to 9.94; p<0.0001) compared with susceptible never-smokers (AOR=2.78, 95% CI 1.84 to 4.20; p<0.0001).

Conclusions

Findings from this large, longitudinal study support public health concerns that e-cigarette use may contribute to the development of a new population of cigarette smokers. They also support the notion that e-cigarettes are expanding the tobacco market by attracting low-risk youth who would otherwise be unlikely to initiate using cigarettes. Careful consideration will be needed in developing an appropriate regulatory framework that prevents e-cigarette use among youth.

Keywords: e-cigarettes, cigarettes, youth, adolescents, susceptibility

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study assessed the relationship between e-cigarette use among never-smoking adolescents and smoking initiation using a large longitudinal sample.

This study examined transitions in smoking behaviour among adolescents at different risk levels (ie, susceptible and non-susceptible never-smokers).

The measures of e-cigarette use used within this study did not provide information regarding the types of e-cigarettes being used.

This study focused solely on cigarette smoking initiation outcomes.

Background

Despite the declining prevalence of smoking in most countries globally, tobacco use remains a threat to global health. In 2013, tobacco use accounted for the loss of approximately 6.1 million lives and 143.5 million disability-adjusted life-years worldwide.1 2 Considering that the majority of smokers try their first cigarette during adolescence,3 preventing youth smoking initiation represents a key public health priority.

Electronic cigarettes are battery-operated devices that deliver nicotine and vaporise a liquid mixture made up of propylene glycol, nicotine, flavouring agents and other constituents. The rise in e-cigarette use among youth has created discussion regarding the public health implications. While some evidence does exist to support the potential of e-cigarettes to be used as smoking cessation aids and help reduce smoking-related harms among adults,4 5 others have argued against this considering the limited evidence of the long-term effects of e-cigarettes.6 On the other hand, given that many adolescent e-cigarette users are never-smokers,7 8 the possibility that e-cigarette use may attract new cigarette smokers among youth populations has been discussed in various studies9 10 A recent meta-analysis by Soneji et al11 found consistent evidence from nine longitudinal studies of an association between initial e-cigarette use among non-smoking adolescents and adults and subsequent cigarette smoking initiation.11 Despite substantial evidence supporting this association,11 most longitudinal studies to date examining this relationship have been based out of USA, with an absence of studies assessing whether this pattern also exists within a Canadian context, where the regulatory environment for e-cigarettes differs from USA. Within Canada, nicotine e-cigarettes are considered medical devices requiring market authorisation before advertisement or sale. Currently, no e-cigarettes with nicotine have received market approval in Canada. It is important to consider whether Canada’s distinct regulatory policies that limit the sale of nicotine-containing e-cigarettes may have an impact on the relationship between adolescent e-cigarette use and subsequent cigarette smoking initiation.

Though substantial evidence exists to support the association between e-cigarette use and subsequent smoking initiation,11 few studies to date have assessed the differential association between e-cigarette use and subsequent smoking initiation among distinct risk groups, including non-susceptible never-smokers (ie, low risk) versus susceptible never-smokers (ie, high risk). Susceptibility to future smoking, defined as the lack of a firm commitment not to smoke among never-smokers, is a validated and reliable predictor of tobacco cigarette smoking initiation among adolescents.12 13 It is hypothesised that the use of e-cigarettes by never-smoking youth may increase their susceptibility to future cigarette smoking. Cross-sectional studies suggest that never-smoking youth who have ever and currently use e-cigarettes are at increased odds of being susceptible to future smoking, with a stronger association identified among younger students.14–16 To our knowledge, only two longitudinal studies have examined the progression from non-susceptible never-smoker to susceptible never-smoker or ever smoker among e-cigarette and non-e-cigarette users; however, both studies included older adolescent and young adult populations. The first longitudinal study identified that youth and young adult non-susceptible never-smokers who used e-cigarettes at baseline were more likely to become susceptible never-smokers and try smoking cigarettes at 1-year follow-up, compared with those who did not smoke e-cigarettes at baseline.17 The second longitudinal study identified that among a sample of older adolescents, non-susceptible never-smokers who used e-cigarettes at baseline were more likely to initiate cigarette smoking after 16 months, compared with never users of e-cigarettes at baseline.18

Previous longitudinal studies assessing the potential association between e-cigarette use and subsequent cigarette smoking initiation among non-smoking youth have focused on older adolescents and young adults and generally had shorter follow-up periods.17 18 These studies have also all taken place in USA. Additional longitudinal work incorporating a sample of younger adolescents, a longer follow-up period and different regulatory contexts is needed to explore the potential association between e-cigarette use and subsequent cigarette use among different risk groups and in different contexts. This study examined whether baseline use of e-cigarettes among a Canadian sample of susceptible and non-susceptible never-smoking youth was associated with cigarette smoking initiation over a 2-year follow-up.

Methods

Design

COMPASS is a prospective cohort study (2012–2021) designed to gather longitudinal and hierarchical data from a sample of secondary school students in Canada.19 This paper reports on longitudinal findings between Year 2 (2013–2014) and Year 4 (2015–2016) of the study among a sample of schools that agreed to the use of active-information passive consent permission procedures. Year 2 data were selected as baseline due to the larger sample size20 and since this was the first year, e-cigarette use was assessed. Data relating to student health behaviours were collected using the COMPASS student questionnaire (Cq). A full description of the COMPASS study along with its methods is available online (www.compass.uwaterloo.ca) and in print.19

Participants

In Year 2, data were gathered from 45 298 grade 9–12 students (response rate of 79.2%) attending 89 secondary schools located within the Canadian provinces of Ontario and Alberta. In Year 4, data were gathered from 40 436 grade 9–12 secondary students (response rate of 79.9%) attending 81 Ontario and Alberta secondary schools. The vast majority of missing respondents were a result of students being absent or on a spare (ie, scheduled free period) during the data collection period; missing respondents due to parental refusal was limited (~0.4%).

Data linkage

To examine longitudinal changes among individuals, we linked student responses at Year 2 and Year 4 using a unique code generated by each student.21 The process of linking student-level data across multiple waves is described in greater depth by Qian and colleagues.22 The linked sample consisted of students who could be followed across both time points. As such, it was not possible to link grade 11 and 12 students in Year 2 who had already graduated and grade 9 and 10 students who were newly admitted to high school in Year 4. A total of 11 215 students who were in grades 9, 10 and 11 at Year 2 could be linked across both time points. Grade 11 students within the linked sample represented students who had not graduated high school with their peers and as such were able to participate in the study at both time points. Furthermore, students who reported ever having tried a cigarette at baseline (n=1527) or who had missing data for any predictors/covariates (n=187) were excluded, leaving a final linked sample of 9501 students. For ease of description, Year 2 will be considered ‘baseline’ and Year 4 will be considered ‘follow-up’.

Measures

Smoking initiation at baseline and follow-up was assessed by asking students: ‘Have you ever tried smoking a cigarette, even a puff or two?’ Individuals who responded ‘yes’ were classified as ever-smokers, while all others were classified as never-smokers. We further classified the ‘never-smokers’ group as susceptible or non-susceptible to future smoking. Susceptibility to future smoking among never-smoking students was assessed at baseline and follow-up using a three-item validated measure: ‘Do you think in the future you might try smoking cigarettes?’, ‘If one of your best friends were to offer you a cigarette, would you smoke it?’ and ‘At any time during the next year, do you think you will smoke a cigarette?’ Consistent with Pierce’s validated construct,12 individuals who responded ‘definitely not’ to all three questions were categorised as non-susceptible to future smoking (ie, low risk). Individuals who responded positively to at least one item were categorised as susceptible to future smoking (ie, high risk).

Current (past 30 day) use of e-cigarettes at baseline was measured by asking students the following question: ‘In the last 30 days, did you use any of the following? (Mark all that apply)’. Students could choose one or more tobacco/nicotine products, including e-cigarettes (‘electronic cigarettes that look like cigarettes/cigars, but produce vapour instead of smoke’). Respondents who reported having used e-cigarettes in the past 30 days were categorised as current e-cigarette users, while all others were categorised as non-current users.

Students also self-reported their gender (male or female), grade (9, 10, 11, 12) and ethnicity (Black, White, Asian, Latin-American, Aboriginal, Other/Mixed) at baseline. Students’ social environment was measured by asking ‘How many of your closest friends smoke cigarettes?’ (‘None’ to ‘5 or more friends’) at baseline. Students’ weekly spending money at baseline was also measured by asking ‘About how much money do you usually get each week to spend on yourself or to save?’ with response options of 0, $1–$5, $6–$10, $11–$20, $21–$40, $41–$100, more than $100 and ‘I do not know how much I get each week’.

Patient and public involvement

There were no patients involved in the development of the research questions and outcome measures, the design of the study or the recruitment to and conduct of the study.

Analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to examine changes in self-reported susceptibility to future smoking at follow-up among never-smokers, stratifying by e-cigarette use and cigarette smoking susceptibility at baseline. Descriptive statistics examined the baseline characteristics of current and non-current e-cigarette users; χ² tests identified differences between current and non-current e-cigarette users at baseline.

For longitudinal analyses, the PROC GENMOD procedure (present on SAS V.9.4) was used to fit generalised estimating equation (GEE) models using the repeated statement. GEE models are an extension of generalised linear models that allow for the analysis of correlated observations (ie, students clustered within schools).23 Using GEE, two logistic regression models assessed the relationship between baseline e-cigarette use and smoking susceptibility at follow-up, stratifying by smoking susceptibility at baseline. The first, a multinomial logistic regression model, assessed whether e-cigarette use among non-susceptible (ie, low-risk) youth at baseline predicted susceptibility to future smoking and smoking initiation at follow-up. The second, a binary logistic regression model, assessed whether e-cigarette use among susceptible (ie, high-risk) youth at baseline predicted smoking initiation at follow-up. Both models controlled for gender, grade, self-reported ethnicity, self-reported spending money and the number of friends who smoke cigarettes at baseline, as these covariates have been seen to influence smoking susceptibility outcomes. The alpha level used for all statistical analyses was 0.05.

Results

Table 1 presents the baseline characteristics of current and non-current e-cigarette users. At baseline, a significantly higher proportion of current (past-30 day) e-cigarette users reported being male, relative to those who had not used e-cigarettes in the past 30 days. A significantly higher proportion of current e-cigarette users also reported having friends who smoked cigarettes and reported being susceptible to smoking cigarettes in the future, relative to those who had not used e-cigarettes in the past 30 days.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of current and non-current e-cigarette users among students who reported never smoking cigarettes at baseline, 2013–2016 COMPASS study

| Variable | Current (past-30 day) e-cigarette users | χ² | |||

| No (n=9295) | Yes (n=206) | df | P values | ||

| Grade | 9 | 54.8 (5098) | 51.5 (106) | 2 | 0.6117 |

| 10 | 42.2 (3923) | 45.6 (94) | |||

| 11 | 2.9 (274) | 2.9 (6) | |||

| Gender | Female | 52.6 (4889) | 37.9 (78) | 1 | <0.0001 |

| Male | 47.4 (4406) | 62.1 (128) | |||

| Race | White | 70.9 (6590) | 65.0 (134) | 5 | 0.0015 |

| Black | 2.6 (239) | 4.9 (10) | |||

| Asian | 4.7 (440) | 1.0 (2) | |||

| Off-Reserve Aboriginal | 0.9 (83) | 1.9 (4) | |||

| Hispanic/Latin American | 1.0 (97) | 2.4 (5) | |||

| Other/Mixed | 19.9 (1846) | 24.8 (51) | |||

| Number of friends who smoke cigarettes | None | 81.7 (7594) | 63.6 (131) | 3 | <0.0001 |

| 1 | 10.7 (997) | 19.4 (40) | |||

| 2 | 4.4 (408) | 8.7 (18) | |||

| 3 or more | 3.2 (296) | 8.3 (17) | |||

| Susceptibility to future cigarette smoking | Not susceptible | 71.2 (6616) | 35.4 (73) | 1 | <0.0001 |

| Susceptible | 28.8 (2679) | 64.6 (133) | |||

| Weekly spending money | 0 | 21.8 (2022) | 11.2 (23) | 4 | <0.0001 |

| $1–$20 | 38.6 (3584) | 36.9 (76) | |||

| $21–$100 | 20.4 (1898) | 29.1 (60) | |||

| More than $100 | 4.9 (454) | 9.7 (20) | |||

| I don’t know how much money I get each week/Not stated | 14.1 (1337) | 13.1 (27) | |||

Figure 1 presents the smoking status at follow-up among baseline never-smokers of tobacco cigarettes. The results are stratified by e-cigarette use and cigarette smoking susceptibility at baseline. Among non-susceptible never-smokers, it is apparent that a higher proportion of current e-cigarette users reported trying tobacco cigarettes at follow-up compared with those who did not report using e-cigarettes in the past 30 days; roughly half of current e-cigarette users at baseline proceeded to trying a cigarette at follow-up. Similarly, among susceptible never-smokers, a larger proportion of current e-cigarette users reported trying cigarette smoking at follow-up compared with those who did not report using e-cigarettes in the past 30 days.

Figure 1.

Smoking status of current and non-current e-cigarette users among baseline non-susceptible and susceptible never-smokers, 2013–2016 COMPASS study.

Figure 2 presents the adjusted odds of being susceptible to future smoking or trying cigarette smoking at follow-up among susceptible and non-susceptible current e-cigarette users at baseline (relative to non-current users). After controlling for relevant covariates, non-susceptible current e-cigarette users at baseline were significantly more likely to become susceptible to future smoking and try cigarette smoking at follow-up relative to non-current e-cigarette users. Similarly, susceptible current e-cigarette users at baseline were significantly more likely to try cigarette smoking at follow-up relative to non-current e-cigarette users.

Figure 2.

Adjusted OR estimate of becoming susceptible to future smoking and trying tobacco cigarette smoking at follow-up among baseline non-susceptible and susceptible never-smokers, 2013–2016 COMPASS study.

Discussion

Within the sample of never cigarette smokers at baseline, this study found that current e-cigarette users were at a higher risk of cigarette smoking initiation after a 2-year follow-up period. These findings were consistent with previous studies that have demonstrated that adolescents with a history of e-cigarette use were at greater risk for future cigarette use compared with non-users of e-cigarettes.10 14 Of concern, the observed association between e-cigarette use and smoking initiation was even stronger among individuals who were not susceptible to future smoking (ie, low risk). These results support public health concerns that electronic cigarette use may contribute towards the development of a new population of cigarette smokers,14 17 even among adolescents at low risk of future smoking experimentation.

The study findings demonstrated that only a small percentage of non-smoking students reported using e-cigarettes in the past 30 days (4.0%). The small proportion of e-cigarette users may be interpreted as unlikely to result in large effects when assessing public health harms brought on by non-smoking youth that transition from using e-cigarettes to traditional cigarettes. However, it should be noted that prior work has demonstrated that a substantial number of Canadian youth have tried using e-cigarettes and that never-smokers comprise the largest population of youth.24 25 Furthermore, our findings clearly demonstrate that never-smokers who reported using e-cigarettes in the past 30 days were at an increased risk of transitioning to cigarette smoking after 2 years. As such, continued surveillance and monitoring of e-cigarette use and its relationship with cigarette smoking among youth populations should be considered a public health priority.

The use of e-cigarettes by non-susceptible never-smoking youth may be explained in part by the availability of appealing flavouring agents including candy or fruit-flavours. Currently, there are over 7000 distinct flavours available for the e-liquid solutions used in e-cigarettes.26 A recent review identified that the preference for sweetened tobacco products was higher among youth than adult populations.27 Previous research has also shown the growing appeal of flavoured tobacco products among Canadian adolescents.28 Banning e-cigarette flavours may be an important step to reduce the appeal of these products to youth.

Additionally, e-cigarette promotion has proliferated through a number of channels including billboards, radio, television advertising, celebrity endorsement and online media platforms.29 30 It may be that the widespread promotion of these products have had unintended consequences of re-normalising cigarette smoking and shifting social norms surrounding smoking, especially among low-risk youth populations.31 32 These marketing strategies may undermine wider tobacco control policies by inadvertently promoting smoking.

Although some evidence exists to support the notion that e-cigarettes may be a less harmful alternative to cigarette smoking,33 it is also important to simultaneously consider the potential for harm creation among a population of non-smoking youth who would not have normally considered trying tobacco cigarettes. E-cigarettes may potentially lead to a rise in cigarette smoking initiation rates, if youth who would not have otherwise tried smoking begin experimenting with e-cigarettes and then transition to using cigarettes and other tobacco products.6 In addition to the harms associated with transitioning to traditional cigarettes, it is also important to consider the health risks nicotine-containing e-cigarettes pose to youth, as nicotine has been seen to alter the developing adolescent brain.34 35 Our findings reinforce the need for a comprehensive approach that addresses all forms of tobacco products in youth-focused prevention efforts, moving forward.

The findings from this study hold important implications at a time when regulation surrounding the sales and promotion of e-cigarettes is either being tabled or passed in various jurisdictions.36 For instance, within Canada, Bill S-5 will aim to regulate the manufacturing, sale, labelling and promotion of e-cigarettes. Some of the measures within this Bill include banning the sale of vaping products to Canadians under the age of 18, restricting the promotion of flavours that are appealing among youth populations (eg, dessert flavours) and limiting promotional activities that would be considered appealing to youth. Our findings lend support to the need for appropriate regulations that will reduce the appeal of e-cigarettes and discourage use among non-smoking youth.

The study has various strengths including the use of a large, longitudinal, school-based sample from two Canadian jurisdictions, Ontario and Alberta. This is one of the few studies documenting the transition from e-cigarette use to cigarette smoking initiation among a non-US sample of non-smoking youth, illustrating that this pattern of behaviour is not specific to US adolescents. Another key strength of this study included the use of passive consent procedures, which reduces the chances of producing a biased sample and increases participation rates.37 However, the study is also subject to some limitations. First, the study used non-probability sampling methods and as such was not representative of all Ontario and Alberta high schools.19 As such, these findings may not be generalisable to other Canadian high schools outside of the study sample. Second, the study was not able to assess the reasons behind e-cigarette use among the baseline sample of current e-cigarette users, as this question was only introduced in Year 4 of COMPASS (2015–2016). However, future longitudinal work may assess the main reasons driving youth e-cigarette use. In addition, the measures of e-cigarette use did not provide any information about the types of e-cigarettes used (eg, flavoured/non-flavoured, with/without nicotine, mod/tank). Thus, associations between specific kinds of e-cigarettes and cigarette smoking initiation could not be examined. Last, this study focused solely on cigarette smoking initiation; future research should focus on examining other outcomes (eg, smoking progression) and also examine relationships between e-cigarette use and initiation of other tobacco products (eg, cigars, cigarillos) among different risk groups.

Conclusion

Among non-smoking youth who were current e-cigarette users, our findings showed an increased risk of progressing to cigarette use after 2 years. Of concern, low-risk youth at baseline were at an even greater risk of cigarette smoking initiation at follow-up. These results suggest that e-cigarettes are expanding the tobacco cigarette market by attracting low-risk youth who would not have otherwise tried using cigarettes. These findings reinforce the need to adopt regulations aimed at reducing the appeal of e-cigarettes and deterring use among youth populations. Additionally, our results point towards the need for sustained efforts focused on deterring the use of all forms of tobacco products, including e-cigarettes.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: STL designed the study. SA and AC formulated the research objectives and plan. Analysis of data was performed by WQ. SA and AC prepared the manuscript. All authors made revisions to the original draft and approved the final submitted version.

Funding: The COMPASS study was supported by a bridge grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Institute of Nutrition, Metabolism and Diabetes through the ‘Obesity—Interventions to Prevent or Treat’ priority funding awards (OOP-110788; grant awarded to STL) and an operating grant from the CIHR Institute of Population and Public Health (IPPH) (MOP-114875; grant awarded to STL). STL is a Chair in Applied Public Health funded by the Public Health Agency of Canada in partnership with CIHR. AC is funded by CIHR.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: Ethics approval was received by the University of Waterloo’s Office of Research Ethics and all participating school boards’ research ethics bodies.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: COMPASS data is stored at the University of Waterloo on a secure server. The principal investigator of COMPASS, STL, maintains ownership of all COMPASS data and will grant access to COMPASS research collaborators, external research groups and students. For researchers looking to gain access to COMPASS data, individuals must successfully complete the COMPASS data usage application form, that is available online (https://uwaterloo.ca/compass-system/information-researchers), which is then reviewed and approved/declined by STL.

References

- 1. GBD 2015 Risk Factors Collaborators. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 2016;388:1659–724. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31679-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organization. Global status report on noncommunicable diseases 2014. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Preventing tobacco use among young people a report of the general surgeon. USA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hartmann-Boyce J, McRobbie H, Bullen C, et al. . Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;9:CD010216 10.1002/14651858.CD010216.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Malas M, van der Tempel J, Schwartz R, et al. . Electronic Cigarettes for Smoking Cessation: A Systematic Review. Nicotine Tob Res 2016;18:1926–36. 10.1093/ntr/ntw119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine. : Stratton K, Kwan LY, Eaton DL, Public Health Consequences of E-Cigarettes. Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press, 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Reid JL, Rynard VL, Czoli CD, et al. . Who is using e-cigarettes in Canada? Nationally representative data on the prevalence of e-cigarette use among Canadians. Prev Med 2015;81:180–3. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.08.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Carroll Chapman SL, Wu LT, Lt W. E-cigarette prevalence and correlates of use among adolescents versus adults: a review and comparison. J Psychiatr Res 2014;54:43–54. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dutra LM, Glantz SA. Electronic cigarettes and conventional cigarette use among U.S. adolescents: a cross-sectional study. JAMA Pediatr 2014;168:610–7. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.5488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Leventhal AM, Strong DR, Kirkpatrick MG, et al. . Association of electronic cigarette use with initiation of combustible tobacco product smoking in early adolescence. JAMA 2015;314:700–7. 10.1001/jama.2015.8950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Soneji S, Barrington-Trimis JL, Wills TA, et al. . Association between initial use of e-cigarettes and subsequent cigarette smoking among adolescents and young adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr 2017;171:788–97. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.1488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pierce JP, Choi WS, Gilpin EA, et al. . Validation of susceptibility as a predictor of which adolescents take up smoking in the United States. Health Psychol 1996;15:355–61. 10.1037/0278-6133.15.5.355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cole AG, Kennedy RD, Chaurasia A, et al. . Exploring the predictive validity of the susceptibility to smoking construct for tobacco cigarettes, alternative tobacco products, and E-cigarettes. Nicotine Tob Res 2017. 10.1093/ntr/ntx265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Barrington-Trimis JL, Berhane K, Unger JB, et al. . The E-cigarette Social Environment, E-cigarette use, and susceptibility to cigarette smoking. J Adolesc Health 2016;59:75–80. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.03.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bunnell RE, Agaku IT, Arrazola RA, et al. . Intentions to smoke cigarettes among never-smoking US middle and high school electronic cigarette users: National Youth Tobacco Survey, 2011-2013. Nicotine Tob Res 2015;17:228–35. 10.1093/ntr/ntu166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Park JY, Seo DC, Lin HC. E-Cigarette use and intention to initiate or quit smoking among US Youths. Am J Public Health 2016;106:672–8. 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Primack BA, Soneji S, Stoolmiller M, et al. . Progression to traditional cigarette smoking after electronic cigarette use among us adolescents and young adults. JAMA Pediatr 2015;169:1018–23. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.1742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Barrington-Trimis JL, Urman R, Berhane K, et al. . E-Cigarettes and Future Cigarette Use. Pediatrics 2016;138:e20160379 10.1542/peds.2016-0379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Leatherdale ST, Brown KS, Carson V, et al. . The COMPASS study: a longitudinal hierarchical research platform for evaluating natural experiments related to changes in school-level programs, policies and built environment resources. BMC Public Health 2014;14:331–2458. 10.1186/1471-2458-14-331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bredin C, Thompson-Haile A, Leatherdale ST. Supplemental sampling and recruitment of additional schools in Ontario. Waterloo, Ontario: University of Waterloo, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bredin C, Leatherdale ST. Methods of linking COMPASS student-level data over time. Waterloo, Ontario: University of Waterloo, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Qian W, Battista K, Bredin C, et al. . Assessing longitudinal data linkage results in the COMPASS study: Technical Report Series. Waterloo, Ontario: University of Waterloo, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zeger SL, Liang KY. Longitudinal data analysis for discrete and continuous outcomes. Biometrics 1986;42:121–30. 10.2307/2531248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Montreuil A, MacDonald M, Asbridge M, et al. . Prevalence and correlates of electronic cigarette use among Canadian students: cross-sectional findings from the 2014/15 Canadian Student Tobacco, Alcohol and Drugs Survey. CMAJ Open 2017;5:E460–7. 10.9778/cmajo.20160167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Reid JL, Hammond D, Rynard VL, et al. . Tobacco Use in Canada: Patterns and Trends. Waterloo, ON: Propel Centre for Population Health Impact, University of Waterloo, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhu SH, Sun JY, Bonnevie E, et al. . Four hundred and sixty brands of e-cigarettes and counting: implications for product regulation. Tob Control 2014;23(Suppl 3):iii3–9. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hoffman AC, Salgado RV, Dresler C, et al. . Flavour preferences in youth versus adults: a review. Tob Control 2016;25(Suppl 2):ii32–9. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bird Y, May J, Nwankwo C, et al. . Prevalence and characteristics of flavoured tobacco use among students in grades 10 through 12: a national cross-sectional study in Canada, 2012-2013. Tob Induc Dis 2017;15:20 10.1186/s12971-017-0124-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. de Andrade M, Hastings G, Angus K. Promotion of electronic cigarettes: tobacco marketing reinvented? BMJ 2013;347:f7473 10.1136/bmj.f7473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Duke JC, Lee YO, Kim AE, et al. . Exposure to electronic cigarette television advertisements among youth and young adults. Pediatrics 2014;134:e29–36. 10.1542/peds.2014-0269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Stanbrook MB. Electronic cigarettes and youth: a gateway that must be shut. CMAJ 2016;188:785 10.1503/cmaj.160728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. McKee M. Electronic cigarettes: proceed with great caution. Int J Public Health 2014;59:683–5. 10.1007/s00038-014-0589-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Glasser AM, Collins L, Pearson JL, et al. . Overview of Electronic Nicotine delivery systems: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med 2017;52:e33–66. 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.10.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Smith RF, McDonald CG, Bergstrom HC, et al. . Adolescent nicotine induces persisting changes in development of neural connectivity. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2015;55:432–43. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.05.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Yuan M, Cross SJ, Loughlin SE, et al. . Nicotine and the adolescent brain. J Physiol 2015;593:3397–412. 10.1113/JP270492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Barraza LF, Weidenaar KE, Cook LT, et al. . Regulations and policies regarding e-cigarettes. Cancer 2017;123:3007–14. 10.1002/cncr.30725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Thompson-Haile A, Bredin C, Leatherdale S. Rationale for using an active-information passive-consent permission protocol in COMPASS. COMPASS Technical Report Series Waterloo, Ontario: University of Waterloo, 2013. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.