Abstract

Introduction

There are two approaches for the treatment of intracranial aneurysm (IA): interventional therapy and craniotomy, both of which have their advantages and disadvantages in terms of treatment efficacy. To avoid overtreatment of unruptured aneurysms (UIA), to save valuable medical resources and to reduce patient mortality and disability rate, it is vital that neurosurgeons select the most appropriate type of treatment to provide the best levels of care. In this study, we propose a refined, prospective, multicentre study for the Chinese population with strictly defined patient inclusion criteria, along with the selection of representative clinical participating centres.

Methods and analysis

This report describes a multicentre, prospective cohort study. As IA is extremely harmful if it ruptures, ethical issues need to be taken into account with regard to this study. Researchers are therefore not able to use randomised controlled trials. The study will be conducted by 12 clinical centres located in different regions of China. The trial recruitment programme begins in 2016 and is scheduled to be completed in 2020. We expect 1500 participants with UIA to be included. Clinical information relating to the participants will be recorded objectively. The primary endpoints are an evaluation of the safety and efficiency of interventional treatment and craniotomy for 6 months after surgery, with each participant completing at least 1 year of follow-up. The secondary endpoint is the evaluation of safety and efficacy of interventional therapy and craniotomy clipping when participants are treated for 12 months. We also address the success of treatment and the incidence of adverse events.

Ethics and dissemination

The research protocol and the informed consent form for participants in this study were approved by the Ethics Committee of Zhujiang Hospital of Southern Medical University (2017-SJWK-001). The results of this study are expected to be disseminated in peer-reviewed journals in 2021.

Trial registration number

Keywords: un-ruptured aneurysms, interventional treatment, craniotomy, prospective

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This represents the first prospective cohort study to provide strategies for the selection of treatment options for aneurysm in China, including a number of clinical centres throughout the country; thus, it can fully represent the Chinese population.

Inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria are in line with foreign research programmes, but have been adopted in the light of China’s national conditions to formulate a reasonable research plan, which incorporates an adequate sample size to but ensures that the study can be completed on time.

The research process will be coordinated by several departments to ensure the quality and reliability of the research data.

The study considers a variety of clinical control factors, and research progress may be reduced as a result.

Introduction

Intracranial aneurysm (IA) is a common cause of subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH) that is estimated to affect between 0.2% and 9% of the population. While the detection rate for unruptured IAs (UIAs) in healthy people can be as high as 3%, these detection rates differ across various countries.1 According to recent research, the overall prevalence of UIA was 7.0% in Chinese adults aged 35–75 years, with women being more affected than men (8.4% vs 5.5%, respectively).2 In the case of unruptured cerebral aneurysms, the natural course of UIA varies according to the size, location and shape of the aneurysm.3 Interventional therapy and craniotomy represent the two main methods for treating UIAs. However, despite our current knowledge of UIA, and even when we consider information relating to pathological, radiological and clinical studies, there are no specific criteria that can be used to select the appropriate treatment strategy. Consequently, there is an urgent global requirement to develop methods which will help to select the most appropriate treatment for UIA.4

A large number of researchers have investigated the treatment options available for IA, and many of these studies have indicated that the postoperative complications associated with interventional therapy are lower than those of craniotomy. However, the short-term and long-term occlusion rates were lower for interventional therapy than for craniotomy.5–9 These studies have also highlighted that the size and anatomical location of aneurysms can exert a significant influence on the effect of treatment.5–9 Interestingly, research failed to identify any significant difference in costs when treatment was compared between endovascular and neurosurgical approaches over the short term.10 The International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial (ISAT) further showed that compared with craniotomy, interventional treatment can clearly improve patient outcome; however, most of the participants in that study had small aneurysms. Consequently, the trial could not definitively conclude that coiling was safer than clipping for all cases of IA.11–14 While controversial, the ISAT did provide us with a degree of understanding of IA.15 16

Previous research has also shown that the risk of IA rupture was 1%–2%, leading to intracranial haemorrhage, a dangerous condition that is associated with a high mortality and disability rate.17 However, while UIAs do not generally rupture during long-term follow-up, medical treatment can increase the bleeding rate and the rate of rupture. Thus, in the absence of any specific guidelines for the treatment of aneurysms, the aims of this study were to assess the safety, efficacy and economic benefits of interventional treatment versus craniotomy, and to propose a scientific strategy for selecting the appropriate form of surgical treatment for UIA that could be deployed across clinics worldwide.

Methods and analysis

Study design

The China Intracranial Aneurysm Project (CIAP) is an ongoing, multicentre trial supported by the National Key Research Development Program. The CIAP predominantly studies five different aspects of aneurysms: (1) the risk of antithrombotic therapy in patients with UIAs complicated by ischaemic cardio-cerebrovascular diseases; (2) the rate of rupture; (3) the risk of rupture and developing a model to predict rupture; (4) treatment options for UIAs; and (5) the development of standardised treatments for early-stage UIA bleeding. This study dealing with one of the subtopics is an observational study.

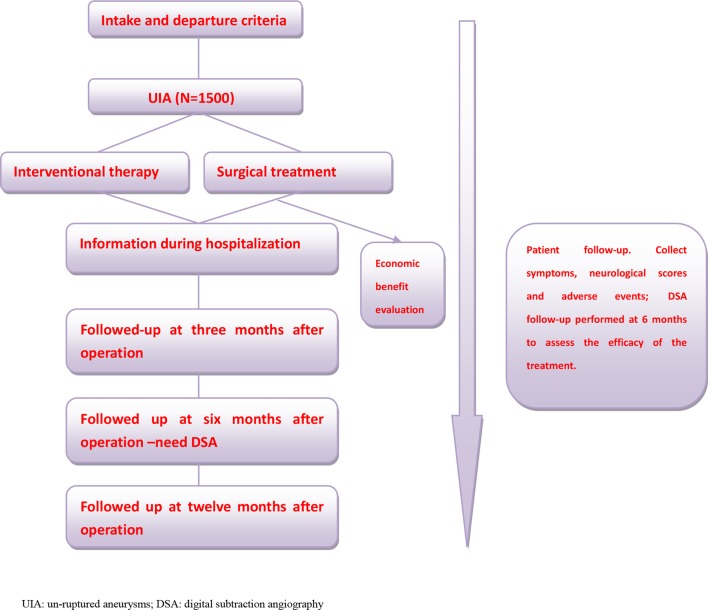

This study evaluates the treatment options for UIAs from the point of view of safety, efficacy and economic benefits, and compares these factors between interventional therapy and craniotomy. The incidence of aneurysms is relatively high among the population, and China is a large country with a wide population distribution. Thus, to fully reflect the population more objectively, the researchers will conduct this multicentre, prospective cohort study for 5 continuous years. Furthermore, referring to previous related research studies and taking into account the characteristics and hazards of UIA, the researchers will not include the random division of participants into groups3; a total of 1500 UIA participants are expected to be included. Each participant will be followed up at fixed time points by researchers, and the normal procedures of treatment will not be affected by participants joining the CIAP study. Follow-up data and other clinical information relating to the participants are recorded in detail, and data are analysed statistically. A concise flow chart of the entire study is shown in figure 1. The trial has been registered at ClinicalTrials.gov with trial registration number NTC03133598.

Figure 1.

Research flow chart.

Participating centre qualification

To evaluate UIA treatment objectively, it is important to avoid participant bias and to ensure that an adequate number of cases is included in the study. We involved participants in multiple centres at the same time and documented the diagnosis and treatment process in detail objectively. The researchers selected 12 clinical centres (each centre covering more than two community or referral units) to conduct this study in collaboration distributed across several regions of China (Southeast, Southwest, Northwest and Northeast). According to an incomplete data set, in 2015, a total of 6000 patients with IA had been evaluated across the 12 clinical centres. Consequently, the researchers believe that each centre can adequately represent the actual level of IA diagnosis and treatment at a regional and national level. The 12 clinical centres used in this study are therefore representative.

There are no specific guidelines for the treatment of UIA. As such, differences exist in the diagnosis and treatment of IA across different regions, different centres and even between different neurosurgeons. In this study, the basic requirement of the neurosurgeons who perform surgery on participants is that they are able to complete more than 30 cases of aneurysm surgery per year independently. The study also features an imaging interpretation centre (internationally recognised image interpretation laboratory, established by Xuanwu Hospital, and the Imaging Center of the University of California, Los Angeles). This centre is responsible for the unified standard interpretation of imaging data arising from the 12 clinical centres.

Participant selection and screening

The purpose of this study is to recruit patients who are suffering from IA without rupture. First, participants are diagnosed with UIA, either by CT angiography (CTA), magnetic resonance angiography or digital subtraction angiography (DSA). Patients with fusiform, traumatic, bacterial or dissecting aneurysms, or with SAH of unknown origin, are excluded. These types of patients, involving other vascular diseases (arteriovenous malformation, arteriovenous fistula), malignant tumours or poor physical condition factors, are expected to live less than a year and are not suitable for study. In order not to disturb the objectivity of the study and to provide good opportunities for follow-up, the researchers also emphasise the ability of participants to live independently (using the modified Rankin scale (mRS) and including those with a score of ≤3). Patients are also excluded if they are unable to communicate normally due to serious mental illness. Patients are also excluded if they receive flow diversion as part of their aneurysm treatment (as flow diversion becomes a standard of care for many large, wide-necked aneurysms that are located in the internal carotid artery), if the size of the aneurysm was less than 3 mm, or if aneurysm diagnosis is unclear or difficult. The specific inclusion and exclusion criteria for the trial are provided in boxes 1 and 2, respectively.

Box 1. Inclusion criteria.

At least one intracranial unruptured aneurysm confirmed by imaging (CTA/MRA/DSA), whether or not there are clinical symptoms.

For patients with multiple aneurysms, the treatment interval is 6 months, regardless of whether they have been treated or not.

Patients currently have the ability to live independently and have an mRS scale score of ≤3.

Age is >14 years old.

Patients or family members agree to provide informed written consent.

CTA, CT angiography; DSA, digital subtraction angiography; MRA, magnetic resonance angiography; mRS, modified Rankin scale.

Box 2. Exclusion criteria.

Intracranial aneurysms associated with unexplained subarachnoid haemorrhage for 30 days.

Patients with other intracranial vascular malformations, such as arteriovenous malformation or arteriovenous fistula.

Patients with intracranial or other parts of the body suffering from malignancy.

Fusiform, traumatic, bacterial or dissecting aneurysms.

Patients with severe mental illness who are unable to communicate when the disease is diagnosed.

Patients with poor overall state, expected survival time less than 1 year or poor physical status, cannot tolerate general anaesthesia, or aneurysm surgeries.

Patients involved in other clinical studies of intracranial aneurysms.

Patients undergoing surgical clipping or endovascular treatment simultaneously.

Patients who receive flow diversion as aneurysm treatment.

Patients who refused to follow up.

The size of the aneurysm ≤3 mm.

The study involves 12 recruiting centres, each of which requires an Institutional Review Board approval before recruiting cases. Patients diagnosed with UIA receive formal diagnosis and treatment for their aneurysms, and along with their families receive full communication from the researchers regarding the aims of the study. Patients can later voluntarily join the study and sign the informed consent form. Once these steps are taken, the participant’s imaging data will be transmitted to the imaging interpretation centre to reconfirm the diagnosis. If the two diagnoses are not consistent, then the participant is excluded. The participants can withdraw from the study at any time, and the researchers can determine whether the participants continue the study according to their physical status. When serious adverse events occur during the course of the trial, the researchers must terminate the study in advance and report to the ethics committee; adverse events are also entered into the case report form (CRF). This study is an observational study that does not interfere with the normal course of clinical diagnosis and treatment; even if participants withdraw from the study, it will not affect their treatment.

Sample size calculation

Sample size is calculated based on the following formula:

(α=0.05, two-sided test, 80% of the degree of control)

According to the results of the International Subarachnoid Un-ruptured Aneurysm ISUA test, the mortality rate of the intervention group was 8.7% at 1 year and that of the craniotomy group was 14.1%, and in the intervention group it was two times as much in the participants as those in the craniotomy group. We calculated our sample size as n=1185 (intervention group: n=395; craniotomy group: n=790). During the study, 20% of the patients would be lost during follow-up; thus, the study requires 1422 participants. Ultimately, we decided to include 1500 participants.

Data collection

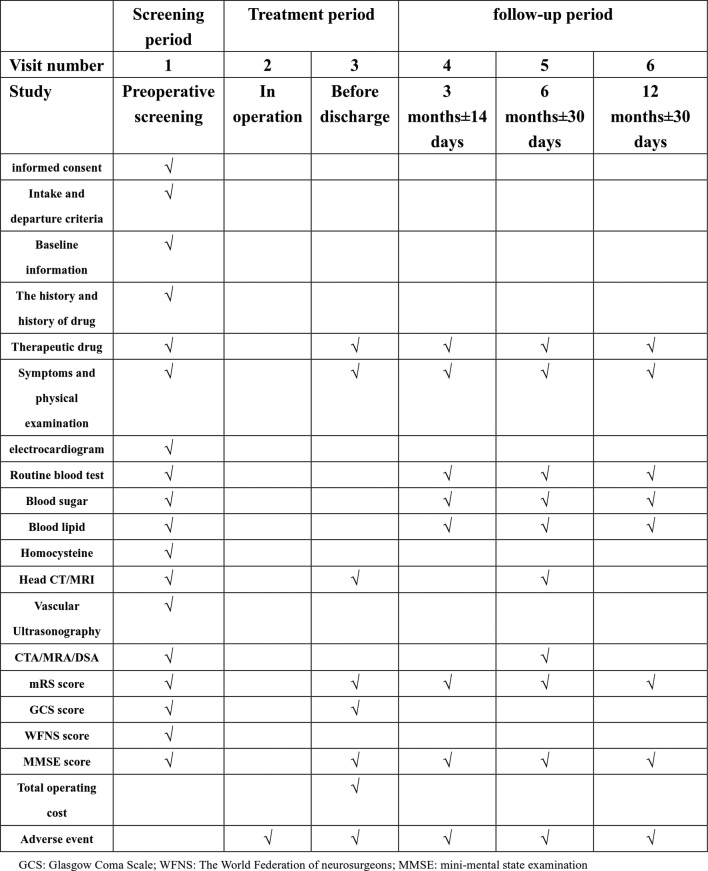

Once participants are included in the study, all information regarding the course of diagnosis and treatment is recorded on the CRF-A. This study also uses an electronic data collection (EDC) system developed by the National Center for Cardiovascular Diseases; information stored on CRFs is entered into the EDC by a designated person at each site, and each site shares data with the EDC. The objective of this study is to objectively compare the safety, efficacy and economic benefits of the two treatment methods for UIA, and each participant is followed for at least 1 year (at 3, 6 and 12 months). Consequently, each participant will have at least 1 year of follow-up data, and when the study is finished the participants will be followed at least once a year up to 5 years. All participants undergo DSA at 18 months. Follow-up data will be acquired by a neurosurgeon either by telephone or by social tools as soon as possible and recorded on the CRF-B. In most cases, DSA examination should be conducted 6 months after the operation to confirm the effect of treatment, which is the vital endpoint of this study. Furthermore, data acquired at 3 and 12 months after surgery are also an important aspect of the study. A detailed follow-up plan is given in figure 2. During the study, the researchers will be obliged to protect the personal privacy and medical information of each participant and strictly adhere to ethical guidelines.

Figure 2.

Participants’ visit and evaluation schedule. CTA, CT angiography; DSA, digital subtraction angiography; MRA, magnetic resonance angiography; mRS, modified Rankin scale.

Data management

As all data will be collected using CRFs and the EDC, the CIAP have established a data management committee (DMC, located at Xuanwu Hospital) to supervise data quality and have hired a specialist data management company responsible for constructing the EDC and ensuring data security, integrity and accuracy. Before the participants are formally enrolled, the DMC will hold CRF and EDC data entry study classes for the main studies in each collaboration clinical centre regarding data entry, modification and retrieval, and setting permissions for the main researchers in the EDC. A clinical research operator supervises progress of the project and quality of data implementation, and the researcher assigned. The clinical research associate (CRA) will regularly visit each participating centre to ensure that all contents of the research programme are strictly followed. If not, the CRA promptly submits information to the investigators. Throughout the project, a research summary conference will be held every 6 months to discuss progress and solve any problems that may arise. This study holds a study summary meeting every 6 months to discuss and solve research question and outcome measures informed by patients’ priorities, experience and preferences.

Data analysis

The Department of Medical Statistics at the National Center for Cardiovascular Diseases will be responsible for all data management and statistical analyses. SPSS V.21.0 statistical software will be used to analyse the results, with normally distributed data being represented by ±SD. Skewed distribution data will be described by the median (M) and the four-quartile range (P25; P75) using an independent t-test or rank-sum test. Categorical variables will be described by frequency, percentage and grouped data, and rate or percentages between the groups will be compared with the χ2 test or by the Fisher’s exact test. Rank data will be analysed by the rank-sum test. P<0.05 will be considered to indicate statistical significance.

Endpoints of the study

The endpoints of the study have also been divided into primary and secondary endpoints. The safety and efficacy of interventional treatment and craniotomy are considered as the primary endpoint of the study and represent the key goals of investigators. Using participant mortality and morbidity rates to evaluate the safety of interventional treatment and craniotomy, and by considering ipsilateral stroke and neurological deficits within 30 days, we shall enhance the safety evaluation of our study, and these features will play a positive role in our findings. Efficacy will be evaluated by aneurysm recurrence rate, rebleeding rate and complete occlusion rate. The secondary endpoint mainly considers the time of postoperative evaluation and the occurrence of adverse events. The primary and the secondary endpoints are described in box 3.

Box 3. Endpoints of the study.

Primary endpoints

-

Main security endpoint.

The safety evaluation of interventional therapy and craniotomy clipping when the participants are treated for 6 months: including participants’ mortality (modified Rankin scale (mRS)=6), morbidity (3≤mRS≤5 points); the emergency of ipsilateral stroke and neurological deficits within 30 days are also recognised as reliability measures to evaluate the security of interventional therapy and craniotomy.

-

Main effectiveness endpoint.

The effectiveness evaluation of interventional therapy and craniotomy clipping when the participants are treated for 6 months: including the recurrence (Raymond classification=1) rate and complete occlusion (Raymond classification=1) rate of aneurysms, and rebleeding rate of subjects.

Secondary endpoints

The safety evaluation of interventional therapy and craniotomy clipping when the participants are treated for 12 months: including participants’ mortality (mRS=6) and morbidity (3≤mRS≤5 points).

The effectiveness evaluation of interventional therapy and craniotomy clipping when the participants are treated for 12 months: including the recurrence (Raymond classification=1) rate and complete occlusion (Raymond classification=1) rate of aneurysms, and rebleeding rate of subjects.

The success rate of treatment.

The success rate of 6 months after interventional therapy or craniotomy clipping (digital subtraction angiography hint: aneurysm completely or nearly total occlusion, recanalisation or regrowth did not appear).

The incidence of major adverse events during hospitalisation.

The incidence of major adverse events after 3 months of surgery.

The incidence of major adverse events in 3 months and 6 months later after operation.

The incidence of major adverse events in 6 months and 12 months later after operation.

Methods of evaluating the economic benefits of treatment

The study combines the following three aspects of patient evaluation in terms of the economic benefits of treatment: admission (Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), World Federation of Neurosurgeons (WFNS), mRS, Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)), the third day after surgery (GCS, WFNS, mRS, MMSE) and the total cost of hospitalisation. Multivariate logistic regression analyses will be used to adjust for GCS, WFNS, mRS and MMSE (admission and the third day after surgery), and then to compare the total cost of hospitalisation for both treatments with control of other economic factors, such as length of stay in the intensive care unit, length of hospital stay, readmission rate, drug changes, adverse events, intraoperation complications postoperative complications and others.

Ethics and dissemination

The study was approved by the China’s Ministry of Science and Technology as a national key research programme in 2016. During the research process, the investigators strictly followed the Declaration of Helsinki and Human Biomedical Research Ethical Issues. Participants will not be affected by the normal course of clinical diagnosis and treatment of aneurysms because of participating in the study. CD is the principal investigator who will supervise the successful implementation of the study. The results of this study will be disseminated in peer-reviewed journals in 2021.

Patient and public involvement

Patients or the public were not directly involved in the study design or conduct of the study. When the participants were included, we told them that this study will take about 5 years to complete, and after the results of the study are published we will inform them by telephone immediately.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, the CIAP is a project exploring the characteristics of IA nationwide among Chinese people and does so from a range of different aspects: the rate of spontaneous aneurysm rupture, risk factors of rupture, the emergency treatment required for ruptured aneurysms and so on. In particular, this study compares two different treatment methods for UIA. IA is a common cause of SAH, but this does not imply that if the SAH rate is high, the incidence of IA is therefore also high18; to a certain extent, SAH can lead to an erroneous understanding of IA. Consequently, we should exclude the unknown causes of SAH.19 DSA has traditionally been considered the gold standard for detecting aneurysms. However, combined with existing data, the present study suggests that the incidence of UIA within the population varies according to the method of examination. The main reason for this finding is that the accuracy of different diagnostic methods is affected by the size of aneurysms. Studies have shown that the sensitivity of DSA is only 85% for small aneurysms (<3 mm) and that the efficacy of CTA for diagnosing IAs is increasingly being recognised1 20–23; this study excludes patients with small aneurysms and in doing so increases the accuracy of the study. However, this finding means that the study can be considered to be incomplete, as it only targets aneurysms of a certain size.

The treatment of IA cannot be separated from interventional treatment and craniotomy. Interventional therapy is becoming increasingly popular among neurosurgeons, but selecting which of the two approaches to use for treatment has been controversial.24–26 Most scholars believe that interventional therapy is associated with lower mortality than is craniotomy; the recurrence and rebleeding rates of interventional therapy are higher,12 and combined with other techniques interventional therapy may achieve better results.5 27 28 The recurrence rate of interventional therapy is higher because for certain types of aneurysms, such as wide-necked aneurysms, the treatment effect is not satisfactory. However, as the intervention materials and technology improve, many scholars have adopted this approach for the treatment of aneurysms and have obtained good results.29–33 Comparing the two methods in terms of safety and efficacy, it is necessary to consider a range of factors, including age, gender, SAH and aneurysm size, because these are the principal factors which can influence the rebleeding of aneurysms.34 35 Surgery can cause haemodynamic changes in an aneurysm, but there is no conclusive evidence to show that this plays a positive role in the recurrence of aneurysms; the study does not take into account the effects of haemodynamics on the results,36 37 but rather the researchers, with the help of a professional statistical team, can try to minimise the impact of baseline data differences on the results.

The authors believe that the most obvious limitations of this study are the following: First, we have included many factors to fully evaluate the economic benefits of treatment. Although there are statistical methods to address these factors, error still exists, and directly comparing total hospital costs, this method may not be highly rigorous. Second, in the study process, there are many factors affecting outcome, including treatment time, drug changes, adverse events and so on. Investigators primarily use retrospective methods to record these data, and the research method is single, resulting in convincing evidence that needs improvement. In addition, our study includes 1500 participants. Whether this sample accurately represents Chinese patients with IA is unknown. There are no national studies to indicate the overall incidence of IA in China, and we can only refer to the existing literature. CIAP subproject 1 aims to indicate the incidence of IA in China.

With careful research design, it is possible to consider and exclude the factors that could potentially influence the results, and by referring to foreign research programmes, this study may provide helpful information for therapeutic strategies for UIA in clinical practice. The results from this study may provide us with a chance of using normative interventions for UIA before deploying interventional treatment and craniotomy, thereby providing significant benefit for patients with aneurysms.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: CD obtained the research funding and is the principal investigator of this study. YC, HF, XL, MH, YQ, XY and HZ have developed the study protocol, and YC is the main author of this article. HF, XH, SG and XL have revised the manuscript. XS, LW, ZW, XT, MZ, AM and ZT are the main people responsible for the seven clinical centres and responsible for implementing this study. CD has approved publication of the final manuscript. YC, HF, XS, LW, ZW, XT, MZ, AM and ZT are responsible for recruitment of patients.

Funding: This study was supported by the National Key Research Development Program (grants no 2016YFC1300804 and 2016YFC1300800) and the Specialized Research Fund for the Doctoral Program of Higher Education (grant no 20124433110014).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Zhujiang Hospital of Southern Medical University (reference number: 2017-SJWK-001) and its respective Institutional Review Board.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Jeon TY, Jeon P, Kim KH. Prevalence of unruptured intracranial aneurysm on MR angiography. Korean J Radiol 2011;12:547 10.3348/kjr.2011.12.5.547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Li MH, Chen SW, Li YD, et al. Prevalence of unruptured cerebral aneurysms in Chinese adults aged 35 to 75 years: a cross-sectional study. Ann Intern Med 2013;159:514–21. 10.7326/0003-4819-159-8-201310150-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Morita A, Kirino T, Hashi K, et al. UCAS Japan Investigators. The natural course of unruptured cerebral aneurysms in a Japanese cohort. N Engl J Med 2012;366:2474–82. 10.1056/NEJMoa1113260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Weir B. Unruptured intracranial aneurysms: a review. J Neurosurg 2002;96:3–42. 10.3171/jns.2002.96.1.0003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chalouhi N, Tjoumakaris S, Gonzalez LF, et al. Coiling of large and giant aneurysms: complications and long-term results of 334 cases. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2014;35:546–52. 10.3174/ajnr.A3696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ausman JI. ISAT study: is coiling better than clipping? Surg Neurol 2003;59:162–5. 10.1016/S0090-3019(03)00074-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Campi A, Ramzi N, Molyneux AJ, et al. Retreatment of ruptured cerebral aneurysms in patients randomized by coiling or clipping in the International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial (ISAT). Stroke 2007;38:1538–44. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.106.466987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ryttlefors M, Enblad P, Kerr RS, et al. International subarachnoid aneurysm trial of neurosurgical clipping versus endovascular coiling: subgroup analysis of 278 elderly patients. Stroke 2008;39:2720–6. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.506030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Scott RB, Eccles F, Molyneux AJ, et al. Improved cognitive outcomes with endovascular coiling of ruptured intracranial aneurysms: neuropsychological outcomes from the International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial (ISAT). Stroke 2010;41:1743–7. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.585240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wolstenholme J, Rivero-Arias O, Gray A, et al. Treatment pathways, resource use, and costs of endovascular coiling versus surgical clipping after aSAH. Stroke 2008;39:111–9. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.482570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Darsaut TE, Jack AS, Kerr RS, et al. International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial - ISAT part II: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2013;14:156 10.1186/1745-6215-14-156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Molyneux AJ, Kerr RS, Yu LM, et al. International subarachnoid aneurysm trial (ISAT) of neurosurgical clipping versus endovascular coiling in 2143 patients with ruptured intracranial aneurysms: a randomised comparison of effects on survival, dependency, seizures, rebleeding, subgroups, and aneurysm occlusion. Lancet 2005;366:809–17. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67214-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Molyneux A, Kerr R, Stratton I, et al. International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial (ISAT) of neurosurgical clipping versus endovascular coiling in 2143 patients with ruptured intracranial aneurysms: a randomized trial. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2002;11:304–14. 10.1053/jscd.2002.130390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Thomas AJ, Ogilvy CS. ISAT: equipoise in treatment of ruptured cerebral aneurysms? Lancet 2015;385:666–8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61736-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Diringer MN. To clip or to coil acutely ruptured intracranial aneurysms: update on the debate. Curr Opin Crit Care 2005;11:121–5. 10.1097/01.ccx.0000155351.93865.81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lindsay KW. The impact of the International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Treatment Trial (ISAT) on neurosurgical practice. Acta Neurochir 2003;145:97–9. 10.1007/s00701-002-1066-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Winn HR, Jane JA, Taylor J, et al. Prevalence of asymptomatic incidental aneurysms: review of 4568 arteriograms. J Neurosurg 2002;96:43–9. 10.3171/jns.2002.96.1.0043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Vlak MH, Algra A, Brandenburg R, et al. Prevalence of unruptured intracranial aneurysms, with emphasis on sex, age, comorbidity, country, and time period: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol 2011;10:626–36. 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70109-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hochberg AR, Rojas R, Thomas AJ, et al. Accuracy of on-call resident interpretation of CT angiography for intracranial aneurysm in subarachnoid hemorrhage. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2011;197:1436–41. 10.2214/AJR.11.6782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mostafazadeh B, Farzaneh Sheikh E, Afsharian Shishvan T, et al. The incidence of berry aneurysm in the Iranian population: an autopsy study. Turk Neurosurg 2008;18:228–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tomycz L, Bansal NK, Hawley CR, et al. "Real-world" comparison of non-invasive imaging to conventional catheter angiography in the diagnosis of cerebral aneurysms. Surg Neurol Int 2011;2:134 10.4103/2152-7806.85607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Teksam M, McKinney A, Casey S, et al. Multi-section CT angiography for detection of cerebral aneurysms. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2004;25:1485–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Menke J, Larsen J, Kallenberg K. Diagnosing cerebral aneurysms by computed tomographic angiography: meta-analysis. Ann Neurol 2011;69:646–54. 10.1002/ana.22270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kis B, Weber W. Treatment of unruptured cerebral aneurysms. Clin Neuroradiol 2007;17:159–66. 10.1007/s00062-007-7018-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Andaluz N, Zuccarello M. Recent trends in the treatment of cerebral aneurysms: analysis of a nationwide inpatient database. J Neurosurg 2008;108:1163–9. 10.3171/JNS/2008/108/6/1163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Komotar RJ, Zacharia BE, Mocco J, et al. Controversies in the surgical treatment of ruptured intracranial aneurysms: the First Annual J. Lawrence Pool Memorial Research Symposium--controversies in the management of cerebral aneurysms. Neurosurgery 2007;62:396–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Coley S, Sneade M, Clarke A, et al. Cerecyte coil trial: procedural safety and clinical outcomes in patients with ruptured and unruptured intracranial aneurysms. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2012;33:474–80. 10.3174/ajnr.A2836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rezek I, Lingineni RK, Sneade M, et al. Differences in the angiographic evaluation of coiled cerebral aneurysms between a core laboratory reader and operators: results of the Cerecyte Coil Trial. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2014;35:124–7. 10.3174/ajnr.A3623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lubicz B, Klisch J, Gauvrit JY, et al. WEB-DL endovascular treatment of wide-neck bifurcation aneurysms: short- and midterm results in a European study. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2014;35:432–8. 10.3174/ajnr.A3869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Conrad MD, Brasiliense LB, Richie AN, et al. Y stenting assisted coiling using a new low profile visible intraluminal support device for wide necked basilar tip aneurysms: a technical report. J Neurointerv Surg 2014;6:296–300. 10.1136/neurintsurg-2013-010818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gory B, Klisch J, Bonafé A, et al. Solitaire AB stent-assisted coiling of wide-necked intracranial aneurysms: mid-term results from the SOLARE Study. Neurosurgery 2014;75:215–9. 10.1227/NEU.0000000000000415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Möhlenbruch M, Herweh C, Behrens L, et al. The LVIS Jr. microstent to assist coil embolization of wide-neck intracranial aneurysms: clinical study to assess safety and efficacy. Neuroradiology 2014;56:389–95. 10.1007/s00234-014-1345-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zhang X, Zhong J, Gao H, et al. Endovascular treatment of intracranial aneurysms with the LVIS device: a systematic review. J Neurointerv Surg 2017;9:553–7. 10.1136/neurintsurg-2016-012403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Vlak MH, Rinkel GJ, Greebe P, et al. Trigger factors and their attributable risk for rupture of intracranial aneurysms: a case-crossover study. Stroke 2011;42:1878–82. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.606558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Guo LM, Zhou HY, Xu JW, et al. Risk factors related to aneurysmal rebleeding. World Neurosurg 2011;76:292–8. 10.1016/j.wneu.2011.03.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cebral JR, Mut F, Weir J, et al. Association of hemodynamic characteristics and cerebral aneurysm rupture. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2011;32:264–70. 10.3174/ajnr.A2274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Cebral JR, Mut F, Weir J, et al. Quantitative characterization of the hemodynamic environment in ruptured and unruptured brain aneurysms. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2011;32:145–51. 10.3174/ajnr.A2419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.