Abstract

Objectives

We piloted an intervention to determine if support from a case manager would assist adults being investigated for tuberculosis (TB) to link into TB and HIV care.

Design

Pilot interventional cohort study.

Participants and setting

Patients identified by primary healthcare clinic staff in South Africa as needing TB investigations were enrolled.

Intervention

Participants were supported for 3 months by case managers who facilitated the care pathway by promoting HIV testing, getting laboratory results, calling patients to return for results and facilitating treatment initiation.

Outcomes measured

Linkage to TB care was defined as starting TB treatment within 28 days in those with a positive test result; linkage to HIV care, for HIV-positive people, was defined as having blood taken for CD4 count and, for those eligible, starting antiretroviral therapy within 3 months. Intervention implementation was measured by number of attempts to contact participants.

Results

Among 562 participants (307 (54.6%) female, median age: 36 years (IQR 29–44)), most 477 (84.8%) had previously tested for HIV; of these, 328/475 (69.1%) self-reported being HIV-positive. Overall, 189/562 (33.6%) participants needed linkage to care (132 HIV care linkage only; 35 TB treatment linkage only; 22 both). Of 555 attempts to contact these 189 participants, 407 were to facilitate HIV care linkage, 78 for TB treatment linkage and 70 for both. At the end of 3-month follow-up, 40 participants had not linked to care (29 of the 132 (22.0%) participants needing linkage to HIV care only, 4 of the 35 (11.4%) needing to start on TB treatment only and 7 of the 22 (31.8%) needing both).

Conclusion

Many people testing for TB need linkage to care. Despite case manager support, non-linkage into HIV care remained higher than desirable, suggesting a need to modify this intervention before implementation. Innovative strategies to enable linkage to care are needed.

Keywords: tuberculosis, public health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The study had a representative sample of adults being investigated for TB from five clinics in two provinces with diverse living conditions and representative of urban as well as periurban setting.

The intervention was well implemented with 555 contact attempts made to participants needing linkage to care.

The lack of a ‘standard of care’ comparison group meant we could not formally determine if the strategy made a difference or not.

Background

People being investigated for tuberculosis (TB) are not linking into TB and HIV care. Studies done in South Africa have shown that 11%–25% people with positive sputum results have ‘pre-treatment loss to follow-up’, defined as not starting on TB treatment either at all, or within a month of sputum submission.1–3 More recently the XTEND (Xpert for TB-Evaluating a New Diagnostic) trial, a pragmatic cluster-randomised controlled trial comparing smear microscopy versus Xpert MTB/RIF (a rapid and more sensitive assay) among adults being investigated for TB showed pretreatment loss to follow-up of 17%, not reduced by use of Xpert MTB/RIF.4 Mortality at 3 and 6 months of sending sputum for microbiological investigation was 3.2% and 5.0%, respectively.4 5 South Africa’s guidelines recommend that all patients with a positive diagnosis for TB as well as those being investigated for TB be tested for HIV.6 The XTEND trial also showed that not being on ART and not knowing one’s HIV status were associated with an increased risk of death,4 suggesting that for persons being investigated for TB and not already on antiretroviral treatment (ART), linkage to HIV care is a priority.

Linking people with a positive HIV test result into HIV care has traditionally involved multiple steps, including undertaking a CD4 count to determine eligibility for ART initiation, with losses at each step.7 Furthermore, TB and HIV care are not fully integrated, making it difficult for patients needing treatment for TB and HIV to access care for both conditions. In an attempt to improve linkage into HIV care among HIV-positive patients, strategies such as case management or health system navigation, using strengths-based case management, where patients identify their strengths and use them to improve their circumstances, have been evaluated.8–10 One such study, a randomised control trial in the USA among recently diagnosed HIV-positive people supported by a case manager, showed that 78% in the intervention arm linked into care successfully compared with the 60% in the control arm.8 Task-shifting of duties such as TB counselling, HIV counselling and testing and ART adherence counselling to lay counsellors has been used as a strategy to relieve short-staffed and overwhelmed healthcare workers in primary healthcare clinics (PHCs).11 In this study, we pilot tested an intervention using lay counsellors to provide support to adults being investigated for TB by following up with patients to ensure that they returned to clinic (1) to receive their TB and HIV-related test results; (2) to do follow-up tests and (3) to start appropriate treatment. This was intended to overcome obstacles such as nurses not having enough time to follow-up patients and the difficulties of making contact with patients. The study objectives were to determine feasibility of implementing the intervention (determined by number of interactions made) and acceptability of the intervention (determined by a qualitative study, reported separately) and to estimate linkage to TB and HIV care.

Methods

Study design

An interventional cohort study was designed to pilot-test case manager support at PHCs for adults being investigated for TB to link them into HIV care and initiate TB treatment where these were clinically indicated. The study was conducted from September 2014 to April 2015 in six PHCs in Mpumalanga and Gauteng provinces, South Africa, which had previously participated in the XTEND trial and were selected on the basis of their high proportions of pretreatment loss to follow-up during that trial. At the time of implementing the case manager study, South Africa’s criteria for ART initiation were a CD4 count of ≤350 cells/mm3 or active TB at any CD4 count. Guidelines also suggested that following a TB diagnosis, ART should be initiated in HIV-positive persons within 2 weeks after TB treatment initiation.

Description of case manager intervention

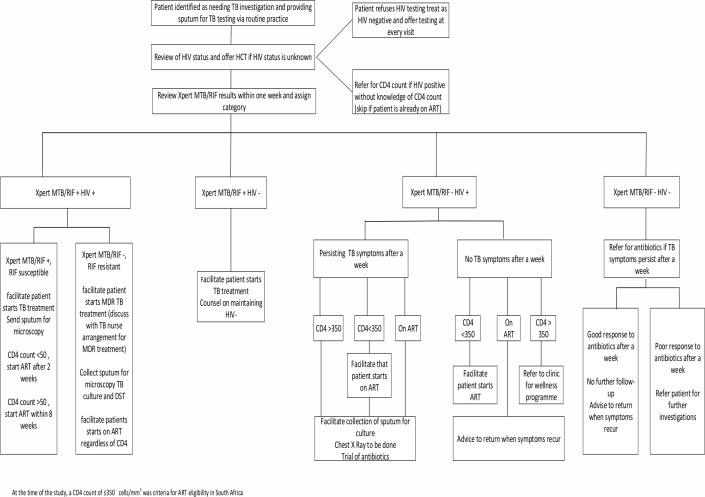

Case managers were lay counsellors, trained by investigators on basic TB and HIV education and national ART and TB management guidelines at the time. One case manager was placed at each of the six clinics. The roles of the case managers were: (1) to follow-up on sputum test results from the laboratory; (2) to call all patients to return to the clinic for their results; (3) to facilitate TB treatment start in patients with a positive sputum test result; (4) to encourage those with unknown HIV status or negative HIV test results older than 3 months at enrolment to test for HIV; and (5) for those who tested HIV-positive or knew themselves to be HIV-positive but did not know their CD4 count at enrolment, to facilitate CD4 count testing, follow-up on CD4 results from laboratory and to facilitate ART initiation if eligible. A study algorithm, based on the national TB management and ART guidelines, was developed to assist the study staff in guiding patients through the health system in seeking appropriate care (figure 1). Case managers attempted to contact participants at least once a week and continued with contact attempts until linkage to care was complete, or the end of study follow-up, 3 months after enrolment. Lists for weekly follow-ups of enrolled participants that needed linkage to care were maintained through the automated release of weekly follow-up case report forms by a smart phone application that was used to collect study data. Contact attempts were made to inform participants of the availability of their results as soon as they were received at the clinics, to remind participants of clinic appointments and to check if patients had returned to clinic for appropriate care. These attempts included inperson meetings at the clinic or telephonic calls. Contacts were categorised as successful if the case manager was able to meet with the participant or speak to the participant telephonically. All decisions about clinical management of participants were made by PHC staff according to their routine practice. Case managers were not actively involved in arranging any additional investigations for TB after enrolment.

Figure 1.

TB and HIV algorithm used to guide case managers. ART, antiretroviral treatment; DST, Drug-susceptibility testing; HCT, HIV Counselling and Testing; MDR, Multi-Drug-resistant; TB, tuberculosis.

Study population and data collection

Participants were eligible for inclusion in the study, based on the criteria previously used in the XTEND trial: if they were aged ≥18 years, identified by PHC staff as needing investigation for TB through TB symptom screen as having any of the four TB symptoms, provided a sputum specimen for TB investigation, able to give informed consent, likely to remain in the study catchment area for 8 months and able to provide adequate locator information, including an alternative contact number for either a friend of family member. Case managers recruited participants who met the inclusion criteria. Data on demographics, current TB symptoms, TB and HIV history and healthcare-seeking behaviour was collected at enrolment. Contact attempts and participants’ progress in linkage into appropriate care was recorded on log forms.

At the end of the follow-up period, the case managers conducted a telephonic or clinic interview with the participant to ascertain if linkage into appropriate care had taken place by collecting self-reported data on HIV testing, TB and ART treatment start dates, health-seeking behaviour and current TB symptoms. Additional data were collected by professional nurses abstracting from clinic records HIV data (such as HIV testing, CD4 count testing and ART start dates) and TB data (TB testing and treatment start dates). Case report forms were completed on a study-specific smartphone application and data submitted in an encrypted format to a central database.4

Description of outcomes and analysis

Linkage into HIV care was defined as at 3 months after enrolment: (1) if HIV status unknown at enrolment: testing HIV-positive, having done a CD4 count and being started on ART if eligible (CD4 count ≤350 cells/mm3 or testing Xpert MTB/RIF positive); (2) if HIV-positive with an unknown CD4 count and not on ART at enrolment: having done a CD4 count test and being started on ART if eligible; (3) if last CD4 count done more than 6 months previously and not on ART at enrolment: having a CD4 count done and being started on ART if eligible. Failure to initiate ART after 3 months when ART eligible at initial assessment was defined as non-linkage to HIV care.

Linkage into TB care (TB treatment initiation) was defined as TB treatment start within 28 days of sputum submission among patients with a positive sputum test result. Non-linkage to TB treatment (pretreatment loss to follow-up) was defined as not starting TB treatment within 28 days of sputum collection among people with a positive TB test result, consistent with definitions in previous studies.2 4

Linkage to HIV care or TB treatment initiation was confirmed by record of ART or TB treatment start date as reported by the participant and documented in study documents or from patient clinic files. Mortality was ascertained by reports by close relatives or friends indicating the death of a participant. Participants were defined as lost to follow-up if at 3 months linkage status was unknown and the participant could not be contacted by case managers.

Contacts attempts were defined as any effort (successful or unsuccessful), done either telephonically or inperson meeting, made by case managers to interact with a patient. The total number of contact attempts per patients was counted, and median attempts needed for linkage into TB and HIV care or both were calculated.

Sample size calculation

This was a pilot study aiming to determine feasibility of implementing the intervention and to estimate linkage to TB and HIV care. The sample size calculation was based on two binary outcomes: (1) uptake of ART among those who were HIV positive and ART eligible; (2) pretreatment loss to follow-up among those who tested TB positive. We had planned to enrol 1200 participants (200 per clinic as in XTEND) with the assumption that 96 (8%) of those tested for TB would test TB positive and need to initiate TB treatment.4 We also assumed that 20 (21%) of people with a sputum testing positive for TB would experience pretreatment loss to follow-up.4 For patients needing linkage to HIV care, the assumption was that 240 (20%) of patients enrolled would not know their HIV status. It was also assumed that 576 (60%) of patients who knew their HIV status would self-report being HIV positive.4 Two hundred and eighty-eight (50%) of those who were HIV positive would not know their CD4 count and would be ART eligible once a CD4 count test was done.4

Risk factor analysis for mortality

Univariable logistic regression analysis was used to assess risk factors for mortality. Due to the small proportion of participants who died by end of 3-month follow-up, categories per predictor variable in the univariable model were restricted to three and a multivariable logistic regression model was not built as a minimum of 10 events per predictor variable is required.12 All statistical analyses were done using Stata V.14.

Patient and public involvement

Patients or public were not involved in the development of research question, outcome measures, study design, recruitment to and conduct of the study. Copies of the study report will be sent to participants who contact the investigators about an interest to receive the study results.

Results

Baseline characteristics

From September to December 2014, 800 adults having a sputum taken for TB investigations in six PHCs were screened and 585 were enrolled. Of these 585, 23 from one site were excluded from analysis because ill health prevented the case manager from undertaking study procedures correctly, leaving 562 from five clinics for analysis. Of the 562 participants, 307 (54.6%) were female, and the median age was 36 years (IQR 29–44) (table 1). The majority of participants (477, 84.8%) self-reported having had an HIV test in the past and of these 328/475 (69.1%) reported being HIV-positive. Of the 328 HIV-positive participants, 156/327 (47.7%) reported having a CD4 count done within the previous 6 months and self-reported median CD4 count was 315 cells/mm3 (IQR 164–471). Over half of the HIV-positive participants with a known CD4 count (209/327 (63.9%)) had never received ART. Ninety-six of 562 (17.1%) of the enrolled participants were previously treated for TB. Five hundred and fourteen of 543 (94.7%) participants reported having at least one TB symptom to the study team, and the majority 452/514 (87.9%) reported having cough (table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study population

| Variable | n (%) n=562 |

| Gender | |

| Female | 307 (54.6) |

| Age (median, IQR) | 36 (29–44) |

| Country of birth | |

| South Africa | 447 (79.5) |

| Ethnic group | |

| Black | 556 (98.9) |

| Highest education completed | |

| No schooling | 23 (4.0) |

| Preschool–Grade 7 | 124 (22.0) |

| Grades 8–12 | 377 (67.1) |

| University/technical qualification | 38 (6.8) |

| Marital status | |

| Single never married | 250 (44.5) |

| Married | 108 (19.2) |

| Cohabitating | 159 (28.3) |

| Divorced/widowed/separated | 45 (8.0) |

| Main income source | |

| Formal employment | 250 (44.5) |

| Self-employment/odd jobs | 134 (23.8) |

| No income | 88 (15.7) |

| Grant/dependence | 90 (16.0) |

| Average monthly income | |

| <ZAR 600 | 34 (6.0) |

| ZAR 601–1000 | 73 (13.0) |

| ZAR 1001–2000 | 120 (21.4) |

| ZAR 2001–4000 | 167 (29.7) |

| Greater than ZAR 4000 | 58 (10.3) |

| Don’t know | 110 (19.6) |

| Ever had HIV test | |

| Yes | 477 (84.9) |

| Self-reported HIV status (n=475)* | |

| Negative | 143 (30.1) |

| Positive | 328 (69.1) |

| Unknown | 4 (0.8) |

| CD4 count known (n=327)† | |

| Yes | 156 (47.7) |

| Self-reported CD4 count, median (IQR) | 315 (164–471) |

| Ever been on ART (n=327) | |

| Never | 209 (63.9) |

| Currently | 116 (35.5) |

| Previously | 2 (0.6) |

| Time on ART in years, median (IQR) n=118 | 2 (0–4) |

| Ever treated for TB | |

| Yes | 96 (17.1) |

| TB symptoms reported (n=543)‡ | |

| Yes | 514 (94.7) |

| Symptoms reported (n=514) | |

| Cough | 452 (87.9) |

| Unintentional weight loss | 311 (60.5) |

| Night sweats | 218 (42.4) |

| Fever | 186 (36.2) |

*Two participants refused to disclose their HIV status.

†Data missing for one participant.

‡Data missing for 19 participants.

ART, antiretroviral treatment; TB, tuberculosis.

Implementation of the intervention

Overall, 189/562 (33.6%) participants required linkage into HIV care or TB treatment initiation or both. Of the 189, 132/189 (69.8%) participants required linkage into HIV care only, 35/189 (18.5%) required TB treatment initiation only and 22/189 (11.6%) required both TB treatment initiation and linkage to HIV care. A total of 555 contact attempts were made by the case managers to these participants: 310/555 (55.9%) were telephonic, 243/555 (43.8%) were contacts at clinic and 2/555 (0.4%) were home visits. Of the 310 telephonic contacts, 211/310 (68.1%) were successful. Of the 99 unsuccessful telephone contact attempts, 98 were due to numbers ringing without an answer and in one the call went to voicemail.

Contact attempts for linkage to HIV care only

Of the 132 people needing linkage to HIV care only, 407 contact attempts in total were made to these individuals with a median of 3 (IQR 2–4) attempts per individual. At the end of the follow-up, 29/132 (22.0%) people had still not linked into HIV care, and a total of 111 contact attempts, with a median of four attempts (IQR 2–4) per individual, had been made to these individuals.

Contact attempts for linkage to TB care only

For people needing to initiate TB treatment only (35), 78 contact attempts with a median of 2 (IQR 1–3) attempts were made. Four (11.4%) of the 35 participants did not initiate TB treatment by end of follow-up period. Ten contact attempts with median of 1 (IQR 1–4) were made to these individuals.

Contact attempts for linkage to TB and HIV care

Seventy contact attempts with median of 3 (IQR 2–4) attempts were made to the 22 participants that needed both to initiate TB treatment and link into HIV care. At end of follow-up, seven (31.8%) of the 22 participants had not completely linked into care as they had started on TB treatment but had not initiated ART. Twenty-seven contact attempts with a median of 2 (IQR 4–5) attempts per individual were made to these seven individuals.

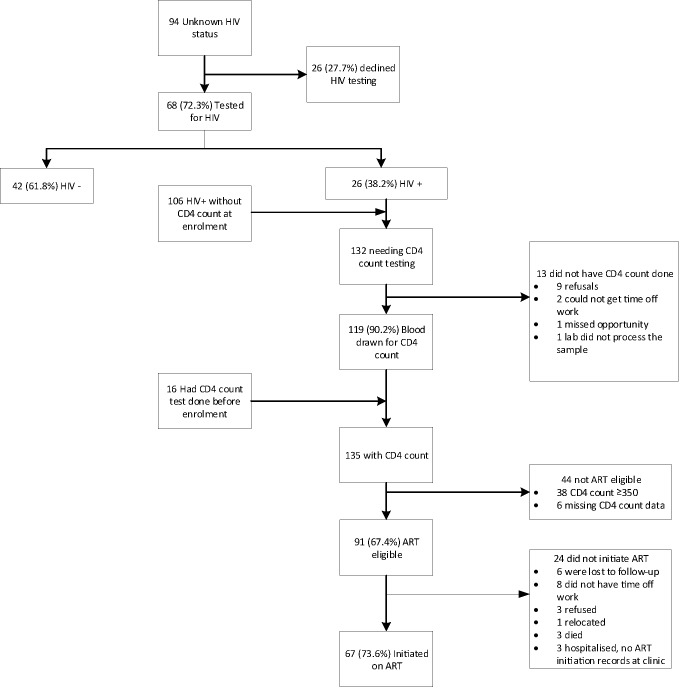

Linkage into HIV care

Participant flow through the steps of linkage to HIV care is shown in figure 2. At enrolment, 94 participants had unknown HIV status or a negative HIV test results older than 3 months and were offered an HIV test. Among the 94, 26 (27.7%) declined to test. Of those who tested, 26/68 (38.2%) were HIV positive. A total of 132 (26 newly tested HIV positive and 106 not on ART with unknown CD4 count) needed a CD4 count, of whom 119/132 (90.2%) had blood taken for a CD4 count by the end of the study. Of the 135 with a CD4 count result (119 who had a new CD4 count and 16 who already knew their CD4 count), 91/135 (67.4%) were ART eligible and 67/91 (73.6%) of those initiated for ART. Of those needing a CD4 count, 13/132 (9.8%) did not have a CD4 count done and 24/91 (26.4%) ART eligible did not initiate ART. The highest proportion of HIV-positive patients were lost at the ART initiation stage (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Flow diagram of linkage into HIV care after 3-month follow-up. ART, antiretroviral treatment.

TB treatment initiation

A total of 57/562 (10.1%) participants had a positive index Xpert MTB/RIF result. Of the 57, 53 (93.0%) started TB treatment within 28 days of testing positive for TB with median time to TB treatment initiation of 5 days (IQR 2–7). Of the four that were not initiated on TB treatment, two died before starting TB treatment and two started TB treatment more than 28 days after sputum was taken. An additional of 22 participants were started on TB treatment after being diagnosed by follow-up tests.

We could not do a risk factor analysis for non-linkage into care because of the complexity of differing denominators at different stages of HIV linkage into care and the low numbers for those who did not initiate TB treatment.

Mortality and loss to follow-up

At the end of the 3-month follow-up, 27/562 (4.8%) participants had died and loss to follow-up was 49/535 (9.2%). Of the 27 participants who died, 18 had self-reported being HIV positive, and 14/18 (77.8%) of them were on ART. Only four of the deceased participants had a TB positive index Xpert MTB/RIF result.

Risk factors of mortality at 3 months after enrolment

Univariable analysis for mortality (table 2) showed weak evidence for an association between having more than one TB symptom (OR 2.4, 95% CI 0.89 to 6.45) and increased risk of death, but a chance finding cannot be excluded.

Table 2.

Univariate analysis for risk factors for mortality

| Variable | Proportion died (%) | OR (95% CI) | P values |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 10/255 (3.9) | 1 | |

| Female | 17/307 (5.5) | 1.43 (0.65 to 3.19) | 0.37 |

| Age group | |||

| >30 | 5/144 (3.5) | 1 | |

| 30–39.9 | 14/210 (6.7) | 1.99 (0.69 to 5.64) | |

| ≤40 | 8/208 (3.8) | 1.11 (0.36 to 3.47) | 0.29 |

| Self-reported HIV status | |||

| Negative | 5/130 (3.8) | 1 | |

| HIV-positive on ART | 4/120 (3.3) | 0.86 (0.23 to 3.28) | |

| HIV-positive not on ART | 14/205 (6.8) | 1.83 (0.64 to 5.21) | 0.29 |

| Number of TB symptoms | |||

| ≤1 | 5/194 (2.6) | 1 | |

| 2 and more | 22/368 (6.0) | 2.4 (0.89 to 6.45) | 0.05 |

| BMI | |||

| <18.5 | 4/78 (5.1) | 0.88 (0.29 to 2.68) | |

| 18.5–24.9 | 18/311 (5.8) | 1 | |

| 25+ | 5/173 (2.9) | 0.48 (0.18 to 1.32) | 0.33 |

ART, antiretroviral treatment; BMI, body mass index; TB, tuberculosis.

Discussion

In our study, 33.6% of people being investigated for TB at PHCs in South Africa required linkage into HIV care or TB treatment initiation. A high proportion of people with positive TB test results started TB treatment with 78 contact attempts made to them. However, despite support with 477 contact attempts from a case manager, a total of 21.9% of those needing HIV care only and 31.8% needing TB and HIV care did not link into HIV care at the end of the 3-month follow-up period with the highest proportion lost at the ART initiation step. By piloting this intervention, we had hoped to overcome obstacles such as nurses not having enough time to follow-up patients and difficulties of making contact with the patients such as clinic phones not working or people having not given their contact numbers. The processes of the intervention largely worked as intended, with multiple contacts to people needing linkage into care. However, HIV linkage care was still suboptimal, suggesting that this intervention as implemented for HIV was insufficient. It also suggests that linkage to HIV care compared with initiation of TB treatment is harder to achieve. This is probably due to the larger number of steps that were necessary for a person to start ART at the time of the study, which included CD4 count testing for ART eligibility assessments, attendance at ART adherence classes and baseline blood tests for assessment of contraindications to specific antiretroviral drugs. This resulted in patients needing to visit the clinic multiple times. South African guidelines now recommend ART for all HIV-positive people regardless of CD4 count. This may reduce losses along the linkage pathway by reducing the number of visits needed.

Some of our study participants refused HIV testing, but the proportions (27.7%) in our study were lower than that found in a South African study done in 2007 comparing uptake of HIV test between provider-initiated testing and counselling and provider referral to voluntary HIV testing among patients attending community health centres.13 The study reported that 45% of patients in the provider-initiated testing group, versus 69% of patients in voluntary HIV testing group, refused HIV testing.13 In a 2012 study, among HIV non-testers from South Africa, barriers to testing included fear of knowing one’s HIV status and fear of what people may say.14 Linkage to care (HIV and TB) in our study was higher compared with Sizanani, a randomised control trial in South Africa done between 2010 and 2013 using health navigators sending short messaging service reminders to newly diagnosed HIV-positive people to link into TB and HIV care.10 This difference is probably because linkage to care was defined differently in Sizanani compared with our study. Standardised definitions of linkage to care would facilitate making comparisons and setting standards.10

A number of participants in our study declined to start on ART because they could not get time off work. This could be because the health system is too difficult or time-consuming for working people to navigate; it could also be that participants not wanting to start ART for other reasons gave this as an excuse for not returning to the clinic. A study determining rates and predictors of declining to start ART in treatment-eligible HIV-positive individuals in South Africa in 2009 showed that 20% refused to start ART and 37% of those reported feeling healthy as a reason for non-initiation.15 Another study, from South Africa in 2010, showed that stigma was the main barrier to initiating ART.16 The limited information available around the reasons for non-linkage to HIV care suggest that the problem is not simply a failure of clinic staff to communicate results but rather a multifactorial challenge with health system, individual and structural components.10

Some interventions have had successes in improving linkage to care. A study in Uganda focusing on improving processes within clinics showed an improvement in ART initiation among HIV-positive patients.17 Another study done in Zambia and Tanzania that combined clinic-based care plus community support showed a reduction in mortality in HIV-positive patients compared with standard of care.18 It is hard to know what exactly made these interventions work, but the Ugandan study differed from our study in that it targeted multiple number of components within the clinic such as staff training, coaching and facility feedback. However, the Zambian and Tanzanian study differed in that community support was provided by a lay worker with a higher qualification than a lay counsellor and trained on monitoring of patients for disease progression as well as drug toxicity. Our intervention tried to address challenges of communication between clinic and patients as well as provide support and encouragement to patients.

Our data showed that among adults with a positive Xpert MTB/RIF sputum result, 93.0% were started on TB treatment with 148 contact attempts made to them. The median time to TB treatment start in our study was 5 days, which is within the recommended national department of health target of 2–5 days.6 We could not quantify the total number of participants who were diagnosed with TB using follow-up tests in our study, as some may have started TB treatment after our follow-up ended. Pretreatment loss to follow-up was lower than the 11%–25% found in previous studies in South Africa, although comparisons are limited by the relatively small numbers in our study.1–4

Mortality was high in our study at 4.8% by 3 months suggesting that people are presenting with advanced disease or when already severely ill. This underscores the importance of early diagnosis and linkage to care.

Strengths of our study include prospectively enrolling a representative sample of adults being investigated for TB from five clinics in two provinces of the country that are diverse in living conditions and population and likely to be representative of urban and periurban practice in South Africa. A limitation of our study is that this was a pilot study and as such had no ‘standard of care’ comparison group; therefore, we cannot formally determine if the strategy made a difference or not. Another limitation is that we did not keep record of TB treatment started after the follow-up period.

Conclusion

In our pilot study assessing the potential effect of a case manager to support linkage into HIV care and TB treatment initiation among adults being investigated for TB, we report a higher than desirable rate of non-linkage into HIV care. This is an indication that the piloted strategy lacks components that are crucial to the successful engagement of patients into HIV care. A qualitative evaluation of the intervention (in progress) may give insights into how this intervention could be improved. This pilot study was planned with the intention to conduct a larger trial afterwards, but our findings suggest that further work be done before the intervention is further evaluated. We recommend that more innovative approaches be explored to find strategies that will improve linkage to HIV care and TB treatment initiation in this population to reduce mortality.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge all the participants enrolled in the study, the study team who assisted with data collection and clinic staff were data collection occured.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors contributed in the design of the study. NM, ADG, VC and KM supervised data collection. NM analysed the data and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. AG, VC, KM and GC provided comments for the revision of the manuscript.

Funding: The study was funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation grant number OPP1034523.

Disclaimer: The funder did not play a part in the design, collection, analysis or interpretation and the writing of the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: Ethical clearance was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of the Witwatersrand reference number M131143 and the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, UK reference number 7124. Participants in the study gave written consent, or witnessed oral consent for participants who could not read or write.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data used for this study can be accessed from the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine repository.

References

- 1. Botha E, den Boon S, Lawrence KA, et al. . From suspect to patient: tuberculosis diagnosis and treatment initiation in health facilities in South Africa. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2008;12:936–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Claassens MM, du Toit E, Dunbar R, et al. . Tuberculosis patients in primary care do not start treatment. What role do health system delays play? Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2013;17:603–7. 10.5588/ijtld.12.0505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bristow CC, Dilraj A, Margot B, et al. . Lack of patient registration in the electronic TB register for sputum smear-positive patients in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Tuberculosis 2013;93:567–8. 10.1016/j.tube.2013.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Churchyard GJ, Stevens WS, Mametja LD, et al. . Xpert MTB/RIF versus sputum microscopy as the initial diagnostic test for tuberculosis: a cluster-randomised trial embedded in South African roll-out of Xpert MTB/RIF. Lancet Glob Health 2015;3:e450–57. 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00100-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. McCarthy K, Fielding K, Grant A, et al. . High risk of early mortality among persons suspected of TB in South Africa. Poster 834 session 145 Conference on retroviruses and opportunistic infections; March, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 6. National tuberculosis management guidelines. South Africa: National Department of Health, 2014. http://sahivsoc.org/Files/NTCP_Adult_TB%20Guidelines%2027.5.2014.pdf (accessed 12 Mar 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bassett IV, Regan S, Chetty S, et al. . Who starts antiretroviral therapy in Durban, South Africa?… not everyone who should. AIDS 2010;24(Suppl 1):S37–44. 10.1097/01.aids.0000366081.91192.1c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gardner LI, Metsch LR, Anderson-Mahoney P, et al. . Efficacy of a brief case management intervention to link recently diagnosed HIV-infected persons to care. AIDS 2005;19:423–31. 10.1097/01.aids.0000161772.51900.eb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Craw JA, Gardner LI, Marks G, et al. . Brief strengths-based case management promotes entry into HIV medical care: results of the antiretroviral treatment access study-II. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2008;47:597–606. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181684c51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bassett IV, Coleman SM, Giddy J, et al. . Sizanani: a randomized trial of health system navigators to improve linkage to HIV and TB care in South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2016;73:154–60. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Languza N, Lushaba T, Magingxa N, et al. . Community health workers: a brief description of the HST experience: Health System Trust, 2011. http://www.hst.org.za/sites/default/files/CHWs_HSTexp022011.pdf (accessed 12 Mar 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 12. Peduzzi P, Concato J, Kemper E, et al. . A simulation study of the number of events per variable in logistic regression analysis. J Clin Epidemiol 1996;49:1373–9. 10.1016/S0895-4356(96)00236-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dalal S, Lee CW, Farirai T, et al. . Provider-initiated HIV testing and counseling: increased uptake in two public community health centers in South Africa and implications for scale-up. PLoS One 2011;6:e27293 10.1371/journal.pone.0027293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mohlabane N, Tutshana B, Peltzer K, et al. . Barriers and facilitators associated with HIV testing uptake in South African health facilities offering HIV counselling and testing. Health SA Gesondheid 2016;21:86–95. 10.4102/hsag.v21i0.938 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Katz IT, Essien T, Marinda ET, et al. . Antiretroviral refusal among newly diagnosed HIV-Infected adults in Soweto, South Africa. AIDS 2011;25:2177–81. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834b6464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bogart LM, Chetty S, Giddy J, et al. . Barriers to care among people living with HIV in South Africa: contrasts between patient and healthcare provider perspectives. AIDS Care 2013;25:843–53. 10.1080/09540121.2012.729808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Amanyire G, Semitala FC, Namusobya J, et al. . Effects of a multicomponent intervention to streamline initiation of antiretroviral therapy in Africa: a stepped-wedge cluster-randomised trial. Lancet HIV 2016;3:e539–48. 10.1016/S2352-3018(16)30090-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mfinanga S, Chanda D, Kivuyo SL, et al. . Cryptococcal meningitis screening and community-based early adherence support in people with advanced HIV infection starting antiretroviral therapy in Tanzania and Zambia: an open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2015;385:2173–82. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60164-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.