Abstract

Introduction

Patients with cancer are at higher risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) than the general population as the malignancy itself and treatment modalities, including medication and surgery, contribute to the risk of developing VTE. Furthermore, patients with cancer developing VTE have a worse prognosis than those without cancer. There are no multicentre prospective data on the occurrence and treatment of VTE in patients with cancer in Japan, and data on the outcomes, complications and incidence of VTE in these patients have not been reported. In addition, Japanese patients with cancer are traditionally treated with unfractionated heparin or warfarin; however, the use of direct oral anticoagulants, which became available in 2014, has not been sufficiently examined in this patient group. Therefore, this multicentre, prospective registry has been designed to capture VTE data from Japanese patients presenting with six cancer types.

Methods and analysis

This registry will enrol 10 000 patients with colorectal, lung, stomach, breast, gynaecological (including endometrial, cervical, ovarian, fallopian tube and peritoneal) or pancreatic cancer between March 2017 and March 2019 and follow them for 1 year. We plan to collect data on the incidences of symptomatic VTE, bleeding events, stroke, systemic embolic events, incidental VTE requiring treatment in patients, overall survival and symptomatic VTE event-free survival.

Ethics and dissemination

All patients will provide written informed consent. Data will remain anonymous and will be collected using an online electronic data capture system. Study protocol, amendments and informed consent forms will be approved by the institutional review board/independent ethics committee at each site prior to study commencement. Results will be disseminated at national meetings and published in peer-reviewed journals.

Trial registration number

UMIN000024942.

Keywords: venous thromboembolism, anticoagulant drugs, direct oral anticoagulants, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, registries

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The strength of this registry is that it is the first large, multicentre, prospective registry in Japan to involve a broad range of cancer types.

The registry involves patients both with and without venous thromboembolism (VTE) and will thus provide outcomes that more accurately represent current practice.

The risk factors for VTE in registry patients are varied and some subgroup analyses may be unachievable due to small sample sizes.

As with all studies involving data collected from actual clinical scenarios in different centres, there may be some discrepancies in the gathering of information.

Not all cancer types will be represented.

Introduction

There are many independent risk factors associated with venous thromboembolism (VTE), such as surgery, trauma, hospitalisation, malignant neoplasm with or without chemotherapy and the use of central venous catheters. A combination of risk factors usually precipitates the occurrence of VTE.1 The risk of VTE is four to seven times higher among patients with cancer than that among the general population2–4; cancer type, stage or combination of various risk factors may contribute to increased VTE occurrence.

There are associations between cancer type and VTE occurrence.4–6 UK data revealed a VTE incidence of 14/1000 people per year (95% CI 13 to 14) for all cancers. Regarding cancer type, the incidence of VTE is the highest for pancreatic cancer at 98/1000 people per year (95% CI 80 to 119), followed by lung cancer at 44/1000 (95% CI 39 to 48), stomach cancer at 37/1000 (95% CI 31 to 45), ovarian cancer at 31/1000 (95% CI 27 to 36), uterine cancer at 11/1000 (95% CI 9 to 14) and breast cancer at 9/1000 (95% CI 8 to 10).4 Systematic review data show somewhat higher incidences for these cancer types: pancreatic cancer: 102/1000 (95% CI 70 to 151); lung cancer: 52/1000 (95% CI 38 to 70); colorectal cancer: 33/1000 (95% CI 21 to 53); and breast cancer: 21/1000 (95% CI 10 to 41).5 In Japanese autopsy data from 99 000 patients (>65 000 patients with cancer), the rate of pulmonary embolism (PE) was 2.3% (95% CI 2.2 to 2.4). The rate of PE for ovarian cancer was 5.4%, whereas rates for cancers of the pancreas, lung, digestive system, breast and uterus were 3.4%, 3.2%, 2.4%, 2.6% and 3.0%, respectively.7 The most common site of venous thrombosis leading to PE is a distal deep vein.8 9 Data indicate that 1 in 10 cases of incidental deep vein thrombosis (DVT) will progress to PE.10 These data suggest that potential DVT complication rates among Japanese patients with cancer are higher than previously reported. In addition, VTE is the second most common cause of death in patients with cancer.11

Patients with cancer with DVT have a worse prognosis than those without DVT.6 11 12 This is because cancer itself increases coagulability.1 13 14 This tendency is particularly relevant in patients with cancer who require surgery because it increases the risk of DVT.1 Furthermore, many cancer treatment modalities—including chemotherapy and medication delivery devices such as central venous catheters—are associated with risk of clotting.1 6 The combination of cancer-related, treatment-related and patient-related factors in patients with cancer increases their overall risk of VTE.1 Additionally, patients with cancer are at risk of bleeding,15 16 which must be taken into account when using traditional VTE management approaches (eg, antithrombotic/anticoagulant therapy).1 14 Low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) is used for VTE treatment and prevention of recurrence in patients with cancer in Western countries; however, unfractionated heparin or warfarin is traditionally used in Japan because VTE treatment and recurrence prevention are off-label uses for LMWH. The availability of direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) therapy in Japan has increased the demand for DOACs in the treatment of patients with VTE. However, effective use of DOACs requires knowledge of various factors involved in the onset of VTE and all available treatment options. Despite this, there are few prospective clinical data on the occurrence and treatment of VTE in Japanese patients with cancer.

Registries provide important information on patients who represent those seen in clinical practice, and are increasingly being used to improve knowledge and patient care.17 Cancer-VTE Registry was designed to prospectively collect data on the occurrence and management of VTE in Japanese patients with cancer. This registry will be the first large-scale prospective study to achieve this objective across six cancer types: colorectal, lung, stomach, breast, gynaecological (including endometrial, cervical, ovarian, fallopian tube and peritoneal) and pancreatic. This study aims to investigate risk factors for the occurrence of VTE and bleeding and to examine the onset of arterial thrombosis including stroke (which has a different frequency and mechanism compared with VTE), transient ischaemic attack (TIA) and systemic embolic events (SEE).

Methods and analysis

Design

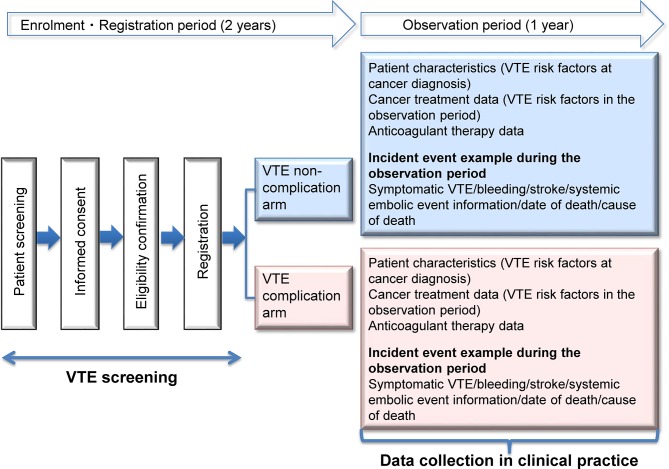

The Cancer-VTE Registry is a cross-sectional cohort study based on a multicentre, prospective clinical registry. The study includes two main components with different study designs: a cross-sectional study aiming to clarify the frequency of VTE complications in the sample population, and a cohort study aiming to determine 1-year patient outcomes (figure 1). Regardless of the presence of VTE complications at registration, we will investigate the event expression and clinical course during the observational study. Thus, patients with VTE complications at registration will be followed up for recurrent VTE.

Figure 1.

Cancer-VTE Registry study design. VTE, venous thromboembolism.

The study does not include any particular intervention; patients will be managed during routine clinical care. Registration will be consecutive when possible. A 1-year observation period was selected because the main event of interest is symptomatic VTE, which is more likely to occur within 1 year of cancer diagnosis (adjusted OR at ≤3 months, 53.5 (95% CI 8.6 to 334.3) and at 3–12 months, 14.3 (95% CI 5.8 to 35.2)), with a significant decrease after 1 year.1

Study period

The study will be conducted between March 2017 and September 2020. Registration will take place between March 2017 and March 2019 (2 years). The observation period will extend until March 2020 (1 year after enrolment of the last patient). Data entry will be completed by September 2020 (6 months after the last observation).

Participants

Patients (outpatients or hospitalised patients) with colorectal, lung, stomach, breast, gynaecological (including endometrial, cervical, ovarian, fallopian tube and peritoneal cancers) and pancreatic cancers at participating study sites will be eligible.

Inclusion criteria will be as follows: age ≥20 years; primary or relapsing colorectal, lung, stomach, breast, gynaecological or pancreatic cancer; planned initiation of cancer therapy (chemotherapy, hormone therapy, molecular targeted therapy, immunotherapy, radiation therapy or surgery); or planned first-line therapy for patients with relapsed cancer; and VTE screening with venous ultrasonography in the 2 months prior to registration. CT angiography of the lower extremities will be acceptable if indicated as part of routine clinical practice. D-dimer assay will also be acceptable when the data are obtained from clinical practice. Patients with a D-dimer concentration of ≤1.2 µg/mL after cancer diagnosis will not be required to undergo VTE screening. The cut-off level is based on a study by Nomura et al, which reported a negative predictive value for VTE of 100% in Japanese patients with a D-dimer concentration ≤1.2 µg/mL.18 Further inclusion criteria are cancer stages II–IV (stages I–IV for gynaecological cancers and stages IB–IV for lung cancer); life expectancy of ≥6 months after registration (or ≥3 months for pancreatic cancer); Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status of 0–2 (0–1 for pancreatic cancer) and provision of informed consent. Patients with active double cancer (synchronous double cancer or metachronous double cancer with a disease-free period within 5 years), patients with only intramucosal cancer and those judged as inappropriate for inclusion or difficult to follow-up by the investigator will be excluded.

Procedures and data sources

Electronic data capture (EDC) will be performed with Viedoc software (PCG Solutions, Tokyo, Japan). The investigators will select patient candidates and obtain written informed consent. VTE screening before any treatments undertaken for primary or relapsing cancer will be completed 2 months prior to registration. Patients not planning cancer surgery also will undergo VTE screening before starting medication (chemotherapy, hormone therapy, molecular therapy and/or immune-checkpoint inhibitors) or radiation therapy. Patients planning cancer surgery will undergo VTE screening prior to undergoing surgery and receiving medication (chemotherapy, hormone therapy, molecular therapy and/or immune-checkpoint inhibitor) or radiation therapy.

The Japan Society of Ultrasonics in Medicine guidelines19 and reference DVD20 that explain diagnostic procedures of venous diseases of lower extremity will be used with the aim of standardising the performance of VTE screening.

VTE complications at baseline will be assessed based on the results of lower extremity venous ultrasonography; however, CT angiography of the lower extremity performed in clinical practice can also be used as an alternative, and VTE screening will not be considered necessary in patients with normal D-dimer concentrations (≤1.2 µg/mL). VTE complications are defined as symptomatic/incidental PE or symptomatic/asymptomatic DVT (proximal and distal DVT) as confirmed by VTE screening. Other complications will be classified as non-VTE complications.

The definition of PE at the time of VTE screening will require that more than one of the following criteria are met: (1) a new filling defect shown on CT pulmonary angiography in part of the segmental branch artery or the proximal blood vessel; (2) a new filling defect, expansion of the existing tube defect or sudden blood flow disruptions (cut-off >2.5 mm diameter) in the blood vessel shown on pulmonary angiography; and (3) a new segmental perfusion defect with normal ventilation shown in ≥75% of pulmonary ventilation/perfusion scintigraphy. If the presence of PE is suspected, it will be confirmed by imaging tests such as CT.

DVT will be diagnosed when blood clots are revealed by the shadow of the thrombus in the deep vein or non-compressed abnormalities in veins, and by indirect observations as perfusion defects in venous ultrasonography. DVT will also be diagnosed in cases where blood clots are shown in deep veins by filling defects on CT angiography of the lower extremity. Central DVT will be defined as DVT occurring in the inferior vena cava, common iliac vein, external iliac vein, internal iliac vein, common femoral vein, femoral vein, deep femoral vein or popliteal vein. Peripheral DVT will be defined as DVT occurring in the peroneal, anterior tibial, posterior tibial, soleal or sural/gastrocnemius vein.

Data management and monitoring

Central and onsite monitoring activities will be conducted to ensure data quality based on data stored by EDC during the study. Source data verification will be performed to identify transcription errors. The event evaluation committee has been established and will perform evaluations independently from the investigators in each study site if there is any doubt regarding the management or evaluation of stored events.

Outcome measures

At baseline, complication rates of VTE and analysis of VTE risk factors will be collected. After 1 year of follow-up, the following data will be collected: incidence of symptomatic VTE; incidence of bleeding events (major or clinically relevant non-major bleeding); incidence of stroke, TIA or SEE; incidence of composite events (symptomatic VTE, stroke, SEE); incidence of incidental VTE requiring treatment; incidence of composite VTE events (symptomatic VTE, incidental VTE requiring treatment); overall survival (OS) and symptomatic VTE event-free survival; rate of mortality from VTE and haemorrhagic complications; rate of mortality from stroke and SEE; duration of anticoagulant therapy; analysis of risk factors for VTE and bleeding; incidence of symptomatic VTE events in each subgroup; and bleeding events (major bleeding or clinically relevant non-major bleeding).

Sample size

The planned sample size is 10 000 patients diagnosed with colorectal, lung, stomach, breast, gynaecological (endometrial, cervical, ovarian, fallopian tube, peritoneal) or pancreatic cancer. The target sample population was set by predicted numbers of patients with each cancer type in Japan.21 There are no prior epidemiological data from multicentre prospective studies in Japanese patients with cancer. Based on previous studies,22–24 we assumed that the incidence of the VTE complication arm would be 10%. The required sample size for the 95% CI half-width of 1.5% is 1500 patients under an incidence rate of 10%. With an 85:15 ratio of VTE non-complication arm to complication arm, the total required sample size will be 8500:1500, or 10 000 patients in total.

Planned population size for each cancer type is as follows: 2500 patients with colorectal cancer (2000 patients planning to undergo surgery or surgery+chemotherapy, or 500 patients before treatment for progression or relapse); 2500 patients with lung cancer (1000 patients planning to undergo surgery or surgery+chemotherapy, or 1500 patients receiving medical treatment for small cell lung cancer (400 patients) or non-small cell lung cancer (1100 patients) with chemotherapy±radiation therapy (800 patients) or epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor (300 patients)); 2000 patients with stomach cancer (1400 patients planning to undergo surgery or surgery+chemotherapy, or 600 patients before treatment for progression or relapse); 1000 patients with breast cancer (700 patients before or after surgery, 100 patients planned for autograft reconstruction, 300 patients planned for neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy (≥6 courses), 300 patients planning to undergo hormone therapy after surgery, or 300 patients who have metastasis or disease relapse); 1000 patients with pancreatic cancer (500 patients planning to undergo surgery and 500 patients not planned for surgery); and 1000 patients with gynaecological cancers.

Data analysis

Demographic data will be first analysed; frequency tables will be developed for categorical variables and summary statistics will be calculated for continuous variables.

For the baseline analysis, the overall baseline VTE complications and baseline VTE complications for each cancer type will be calculated. Multivariate linear and logistic regression will be used to assess the independent associations between baseline VTE complications and possible risk factors.

During the observation period, incidence rates and 95% CIs will be calculated for the first six outcomes (ie, incidence of symptomatic VTE; bleeding events; stroke, TIA, SEE; composite events (symptomatic VTE, stroke, SEE); incidental VTE needing treatment; and composite VTE events).

All time-to-event data including OS, VTE event-free survival, time to VTE-related or bleeding-related death, and time to stroke-related or SEE-related death will be summarised using Kaplan-Meier methods, and HR will be calculated using the Cox proportional hazards model.

The mean value and summary statistics of the period of anticoagulant therapy will also be calculated. Univariate and multivariate analyses will be performed to specify the risk factors influencing the incidence of VTE and bleeding events, respectively. The incidence rates of VTE and bleeding events will be calculated in each subgroup. Data of the patient population with gynaecological cancers will be obtained from an investigator-initiated study, and integrated analysis will be performed.

Ethics and dissemination

This study will be conducted according to the Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subjects and the ethical principles originating from the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants will provide written informed consent before entering the study. The protocol, amendments and patient informed consent forms will be approved by the institutional review board/independent ethics committee at each site prior to study commencement.

For database management and to ensure patient privacy, patients will be registered and their data collected via the EDC system. The ‘Act on the Protection of Personal Information’ (Act No. 57 of 30 May 2003) and related notifications will be applied to patient information. All personnel involved in conducting the study will routinely follow this act and ensure the confidentiality of all patient information and the privacy of all participants. Patient information will be anonymised by the clinical trial registration number connected to confidential information. Potentially identifiable patient information such as medical record numbers in clinical practice, names and contact details will not be recorded in the EDC. Data collected from the patients in this study will not be used for any other purpose, and potentially identifying information will not be published.

Discussion

By collecting information on VTE, bleeding events and treatment modalities in Japanese patients with cancer, this registry may be beneficial in determining suitable anticoagulant therapies for such patients in the future. It is anticipated that integrated analysis data on cancer types will be presented first, followed by data for cancer subtypes and then subgroup analyses.

Conclusion

We plan to present the results of this study at national meetings; cross-sectional results will be submitted for consideration for publication. We anticipate that the data gathered and generated using this registry will create evidence and improve strategies for the prevention, detection and treatment of VTE among patients with cancer in Japan.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the event evaluation committee, Mikio Mukai, Satoru Fujita and Masahiro Yasaka; the venous ultrasonography adviser, Hiroshi Matsuo; chief of statistical analysis, Mari Ohba, who is overseeing the analysis of study data by Mediscience Planning Inc; and the blood coagulation marker adviser, Hideo Wada. The authors also thank Nicola Ryan and Hikari Chiba of Edanz Medical Writing for providing medical writing assistance.

Footnotes

Contributors: YO, MI, HK, MS, TO, HM, KF, MN, TK, KI and MS conceived and designed the study. YO, TK and KI drafted the protocol of the study and organised the study implementation. YO, MI, HK, MS, TO, HM, KF, MN, TK, KI and MS refined the study protocol and study implementation. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This study is funded by Daiichi Sankyo, which initiated the study and was involved in the protocol development, selection and/or advice around selection of the contract research organisation, and in the statistical analysis plan development, and will be involved in the interpretation of results.

Disclaimer: Daiichi Sankyo will not be directly involved in the data management, source data verification or the statistical analysis.

Competing interests: All authors have received personal fees from Daiichi Sankyo during the conduct of study. KF has received research grants from Daiichi Sankyo. TK and KI are employees of Daiichi Sankyo.

Ethics approval: Independent ethics committee/institutional review board at each site.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Japanese guidelines for the diagnosis, treatment and prevention of pulmonary thromboembolism and deep vein thrombosis. 2009. http://www.j-circ.or.jp/guideline/pdf/JCS2009_andoh_h.pdf

- 2. Blom JW, Doggen CJ, Osanto S, et al. . Malignancies, prothrombotic mutations, and the risk of venous thrombosis. JAMA 2005;293:715–22. 10.1001/jama.293.6.715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Heit JA, Silverstein MD, Mohr DN, et al. . Risk factors for deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: a population-based case-control study. Arch Intern Med 2000;160:809–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Walker AJ, Card TR, West J, et al. . Incidence of venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer - a cohort study using linked United Kingdom databases. Eur J Cancer 2013;49:1404–13. 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.10.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Horsted F, West J, Grainge MJ. Risk of venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med 2012;9:e1001275 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Timp JF, Braekkan SK, Versteeg HH, et al. . Epidemiology of cancer-associated venous thrombosis. Blood 2013;122:1712–23. 10.1182/blood-2013-04-460121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sakuma M, Fukui S, Nakamura M, et al. . Cancer and pulmonary embolism: thrombotic embolism, tumor embolism, and tumor invasion into a large vein. Circ J 2006;70:744–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ro A, Kageyama N. Clinical significance of the soleal vein and related drainage veins, in calf vein thrombosis in autopsy cases with massive pulmonary thromboembolism. Ann Vasc Dis 2016;9:15–21. 10.3400/avd.oa.15-00088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ro A, Kageyama N, Tanifuji T, et al. . Pulmonary thromboembolism: overview and update from medicolegal aspects. Leg Med 2008;10:57–71. 10.1016/j.legalmed.2007.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Geerts WH, Heit JA, Clagett GP, et al. . Prevention of venous thromboembolism. Chest 2001;119:132S–75. 10.1378/chest.119.1_suppl.132S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Khorana AA. Venous thromboembolism and prognosis in cancer. Thromb Res 2010;125:490–3. 10.1016/j.thromres.2009.12.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sørensen HT, Mellemkjær L, Olsen JH, et al. . Prognosis of cancers associated with Venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med Overseas Ed 2000;343:1846–50. 10.1056/NEJM200012213432504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ikushima S, Ono R, Fukuda K, et al. . Trousseau’s syndrome: cancer-associated thrombosis. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2016;46:204–8. 10.1093/jjco/hyv165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Guidelines Version 2. 2014 Cancer-associated venous thromboembolic disease. https://http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.asp

- 15. Hutten BA, Prins MH, Gent M, et al. . Incidence of recurrent thromboembolic and bleeding complications among patients with venous thromboembolism in relation to both malignancy and achieved international normalized ratio: a retrospective analysis. J Clin Oncol 2000;18:3078–83. 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.17.3078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Prandoni P, et al. . Recurrent venous thromboembolism and bleeding complications during anticoagulant treatment in patients with cancer and venous thrombosis. Blood 2002;100:3484–8. 10.1182/blood-2002-01-0108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Krumholz HM. Registries and selection bias: the need for accountability. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2009;2:517–8. 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.109.916601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nomura H, Wada H, Mizuno T, et al. . Negative predictive value of d-dimer for diagnosis of venous thromboembolism. Int J Hematol 2008;87:250–5. 10.1007/s12185-008-0047-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tanaka S, Nishigami K, Taniguchi N, et al. . Criteria for ultrasound diagnosis of deep venous thrombosis of lower extremities. J Med Ultrason 2008;35:33–6. 10.1007/s10396-007-0160-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Matsuo H, Sato H. Vascular Ultrasound: Screening for venous diseases of lower extremity [DVD. Osaka: MEDICUS SHUPPAN, Publishers Co. Ltd, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Japan cancer statistics 2015 Available from: http://ganjoho.jp/reg_stat/statistics/stat/short_pred_past/short_pred2015.html (accessed 15 Mar 2017).

- 22. The Hokusai-VTE Investigators. Edoxaban versus Warfarin for the Treatment of Symptomatic Venous Thromboembolism. N Engl J Med Overseas Ed 2013;369:1406–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Raskob GE, van Es N, Segers A, et al. . Edoxaban for venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer: results from a non-inferiority subgroup analysis of the Hokusai-VTE randomised, double-blind, double-dummy trial. Lancet Haematol 2016;3:e379–e387. 10.1016/S2352-3026(16)30057-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lee AYY, Levine MN, Baker RI, et al. . Low-molecular-weight heparin versus a coumarin for the prevention of recurrent venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer. N Engl J Med Overseas Ed 2003;349:146–53. 10.1056/NEJMoa025313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.