Abstract

Introduction

Treatments aiming at reperfusion of the acutely ischaemic brain tissue may result futile or even detrimental because of the so-called reperfusion injury. The processes contributing to reperfusion injury involve a number of factors, ranging from blood–brain barrier (BBB) disruption to circulating biomarkers. Our aim is to evaluate the relative effect of imaging and circulating biomarkers in relation to reperfusion injury.

Methods and analysis

Observational hospital-based study that will include 140 patients who had ischaemic stroke, treated with systemic thrombolysis, endovascular treatment or both. BBB disruption will be assessed with CT perfusion (CTP) before treatment, and levels of a large panel of biomarkers will be measured before intervention and after 24 hours. Relevant outcomes will include: (1) reperfusion injury, defined as radiologically relevant haemorrhagic transformation at 24 hours and (2) clinical status 3 months after the index stroke. We will investigate the separate and combined effect of pretreatment BBB disruption and circulating biomarkers on reperfusion injury and clinical status at 3 months. Study protocol is registered at http://www.clinicaltrials.gov (ClinicalTrials.gov ID: NCT03041753).

Ethics and dissemination

The study protocol has been approved by ethics committee of the Azienda Ospedaliero Universitaria Careggi (Università degli Studi di Firenze). Informed consent is obtained by each patient at time of enrolment or deferred when the participant lacks the capacity to provide consent during the acute phase. Researchers interested in testing hypotheses with the data are encouraged to contact the corresponding author. Results from the study will be disseminated at national and international conferences and in medical thesis.

Trial registration number

Keywords: stroke, reperfusion injury, thrombolysis, endovascular treatment, blood brain barrier

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Using a definite protocol, a prospective collection of data, and an adequate number of patients assuring statistically powered data, Reperfusion Injury after ischemic Stroke Study (RISKS) can integrate substantially scanty clinical information about biological factors involved in reperfusion injury after cerebral ischaemia.

RISKS combines advanced neuroimaging techniques for the study of blood–brain barrier disruption with analyses of circulating biomarkers as potential predictors of reperfusion injury after acute phase interventions.

A limitation of the study is the lack of a control group of patients who had a stroke not treated with revascularisation therapies.

Another limitation is that study will include patients with acute ischaemic stroke treated with intravenous thrombolysis, endovascular treatment or both. This heterogeneity might influence levels of circulating biomarkers at 24 hours.

A further limitation is the lack of standardisation for the assessment of recanalisation.

Introduction

Ischaemic stroke is a major cause of death and disability. The target of treatments aiming at recanalisation of the occluded vessel is the reperfusion of the ischaemic brain tissue. However, reperfusion of the acutely ischaemic tissue may result clinically futile, or even detrimental because of the so-called reperfusion injury.1 Reperfusion injury is a pathophysiological term that describes complex biochemical mechanisms that may boost the damage of the ischaemic tissue, even with successful recanalisation of the occluded vessel.2 Haemorrhagic transformation (HT) may be considered as expression of the reperfusion injury. Preliminary evidence showed that the disruption of the blood–brain barrier (BBB), which can be investigated by MR techniques3 or CT using permeability maps,4 is a key phenomenon of the reperfusion injury.1 2 Experimental studies on cerebral ischaemia have demonstrated that a number of biological factors, including inflammatory mediators, matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and endothelial function mediators may contribute to reperfusion injury.5 Specifically, unbalance of MMP levels and their natural inhibitors (tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases) seem to be associated with disruption of BBB and increased risk of HT.6–8 However, scanty clinical data exist about relationships between circulating and imaging biomarkers of reperfusion injury.9 10 In this single-centre, prospective observational study of patients who had an ischaemic stroke treated with recanalisation therapies, we plan to investigate the separate effect of pretreatment BBB disruption and circulating biomarkers on reperfusion injury. Moreover, we will investigate the combined effect of BBB disruption and circulating biomarkers in relation to reperfusion injury. Results may help to identify imaging and circulating biomarkers useful for selection of patients in future clinical trials.

Methods

Design

This is an observational prospective single-centre hospital-based study that will include 140 consecutive patients who had an ischaemic stroke. Circulating biomarkers sampling and CTP will be performed before acute interventions. Clinical, imaging and circulating biomarkers assessment will be repeated 24 hours after interventions. Clinical evaluation will be repeated 3 months after the index stroke (table 1). Study protocol is registered at http://www.clinicaltrials.gov (ClinicalTrials.gov ID: NCT03041753).

Table 1.

Schedule of assessment

| Clinical data | 0 (pretreatment) |

24–36 hours | 7 days/discharge | 3 months |

| Demographic variables | x | |||

| Functional status (mRs) | x | x | ||

| Vascular risk factors | x | |||

| Medications | x | x | x | x |

| NIHSS | x | x | x | x |

| Blood pressure | x | x | x | x |

| Neuroimaging | ||||

| Plan CT | x | x | ||

| CT perfusion | x | |||

| CT angiography | x | |||

| Recanalisation assessment (CT angiography, MR angiography and transcranial Doppler) | x | |||

| Blood samples | x | x |

mRs, modified Rankin scale; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale.

Study population

The study will include patients who had an acute ischaemic stroke in the anterior circulation with National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) ≥711 within 12 hours from last time seen well, treated with systemic thrombolysis, endovascular treatment or both. Poststroke functional status will be measured with the modified Rankin Scale (mRS) administered at 3 months by visit or phone interview. We will rate HT grade using the European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study (ECASS II) criteria.12 Collection of clinical data will be blinded to the biomarkers’ results. Key inclusion and exclusion criteria are summarised in table 2.

Table 2.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

| Acute stroke eligible for systemic thrombolysis or endovascular treatment or both | Ischaemic stroke in posterior circulation |

| Age ≥18 years | Contraindication for iodine contrast medium |

| NIHSS ≥7 | >12 hours from last time seen well |

NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale.

Imaging protocol

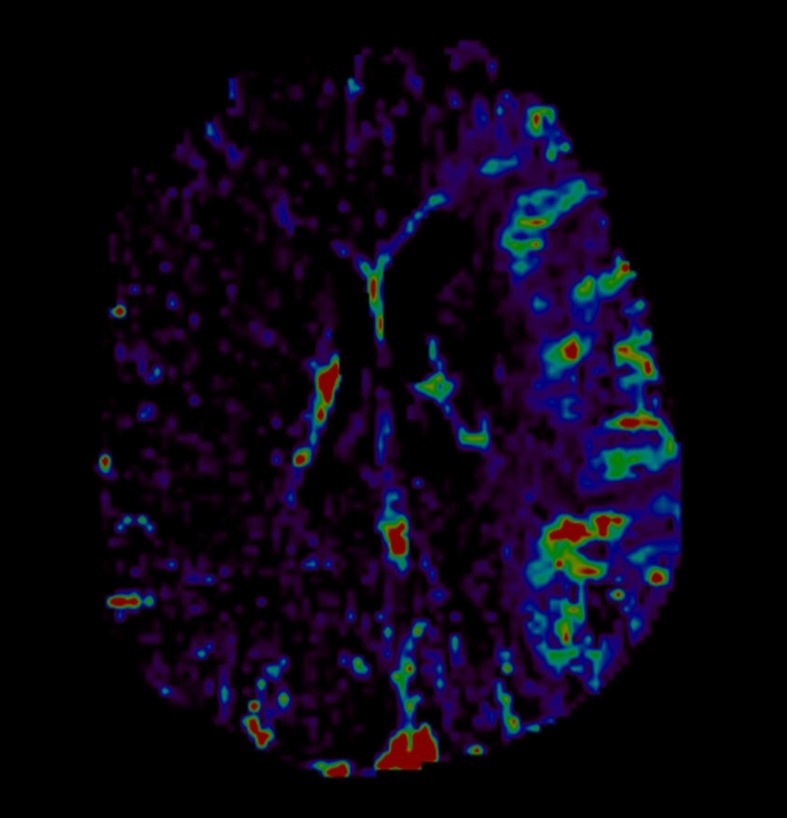

Cerebral imaging will include baseline plain CT, CT angiography and CT perfusion (CTP). CT will be repeated at 24 hours and at any time if clinical deterioration occurs. Collection of imaging data will be blinded to both clinical and laboratory data. Baseline and follow-up CT scans will be assessed by three stroke physicians (FA, BP and VP) for presence of early ischaemic signs (Alberta Stroke Programme Early CT score and hyperdensity of middle cerebral artery) and presence and severity of small vessel disease markers. Cerebral oedema will be assessed according to the Safe Implementation of Thrombolysis in Stroke-Monitoring Study protocol.13 We will rate white matter changes with the Van Swieten Scale, then will combine the posterior (range 0–2) and anterior (range 0–2) scores into a five-point ordinal scale (0–4).14 We will record the presence and number of lacunes, defined as round or ovoid shaped small cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) attenuation areas ≤2 cm in diameter in subcortical white and deep grey matter.15 We will define brain atrophy as deep or cortical and will score with a three-point ordinal scale as none, moderate or severe against a reference CT brain template,16 then will combine the single scores into global atrophy five-point ordinal scale. Presence and site of vessel occlusion will be assessed with CT angiography scans. Presence and grade of collaterals will be assessed with multiphase CT angiography sequences. Collaterals will be graded into good, moderate and poor, according to the original publication.17 We will assess presence and grading of HT on 24 hours CT scan according to ECASS II criteria12 when visible at the follow-up CT scan. CTP studies will be performed with a two-phase acquisition protocol, and permeability maps will be generated for each patient by Olea Sphere 3.0 (Olea Medical, La Ciotat, France) at baseline with a deconvolution-based delay-insensitive algorithm (figure 1). For permeability calculation, we will use Extended Tofts Model (Ktrans=mL/100 g/min).18

Figure 1.

CT perfusion. Permeability map of middle cerebral artery territory on the affected side compared with the contralateral hemisphere.

In case of patients with no clinical improvement, we will assess recanalisation at 24 hours with either CT angiography, MR angiography or transcranial Doppler. In patients treated with endovascular procedures with effective recanalisation and clinical improvement, we will not reassess recanalisation at 24 hours, and we will assume the recanalisation to be as it was at the end of the endovascular treatment.

Laboratory protocol

Blood will be collected before and 24 hours after acute interventions. Tubes will be centrifuged at room temperature at 1500×g for 15 min, and the supernatants will be stored in aliquots at −80°C. The complete list of biomarker under study is depicted in table 3. Novel candidates that will emerge over the course of the study will be considered for analysis. Thrombus obtained after endovascular procedure will be placed into RNA stabilisation reagent and stored at −80°C for global gene expression analysis.

Table 3.

List of biomarkers

| Biomarkers | Methods | Rationale |

| Metalloproteinases and inhibitors | ||

| Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) 1, 2, 3, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12, 13, (EMMPRIN) | Multiplex technology (R&D System, Milan, Italy) | Numerous studies have documented increases in MMPs, specifically MMP-9 levels following stroke with disruption of the blood–brain barrier (BBB)23 |

| TIMP 1, 2, 3, 4 | R&D assays (R&D System) | |

| MMP 2, 9 Activity | Polyacrylamide gel (Precast Bio-rad Criterion 10% Zymogram Gelatin) | |

| Endothelial dysfunction and inflammation | ||

| von Willebrand factor (vWf), D-Dimer, PAI-1 | Immunoturbidimetric method ACL TOP (Instrumentation Laboratory) PAI-Ag ELISA (Technoclone) |

In experimental models, systemic inflammation seems to alter the kinetics of cerebrovascular tight junction determining BBB disruption.24 |

| IL-1, IL-1beta; IL-4, IL-10, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, IL17, IFNγ, TNF-alpha, VEGF, MIP-1 alpha/beta, IP-10, Monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1), CRP, A2M, haptoglobin, P-selectin, E-selectin | Multiplex technology (BioPlex 200 System; BioRad, Italy) | |

| ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 | Multiplex technology (BioPlex 200 System) | |

A2M, alpha2 macroglobulin; CRP, C reactive protein; EMMPRIN, Extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer; ICAM-1, intercellular adhesion molecule 1; IFN, interferon; IL, interleukin; IP-10, IFN gamma-inducible protein 10; MIP, macrophage inflammatory protein; PAI-1, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1; TIMP, tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase; TNF, tumour necrosis factor; VCAM-1, vascular cell adhesion protein 1; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

Treatment or intervention

No adjunctive selective study-related interventions are planned. Patients are treated following current guidelines.

Primary endpoint

Relevant HT (defined as haemorrhagic infarction type two or any type of parenchymal haemorrhage (PH1 and PH2)) at 24 hours CT.

Secondary endpoints

Symptomatic HT (defined as any deterioration in NIHSS score or death combined with intracerebral haemorrhage of any type) at 24 hours CT.

Categorical shift in mRS score 3 months after the index stroke.

Statistical analysis

We will describe general characteristics of the study population, and test differences using Pearson χ2 for categorical variables, analysis of variance and Mann-Whitney U test for numeric variables, as appropriate. BBB disruption and differences in biomarkers levels between baseline and 24 hours will be evaluated according to their distribution. In case of skewed distribution of biomarker values, we will consider the possibility of log-transformation of data. Considering a possible effect of systemic thrombolysis on biomarker levels, the patient cohort will be divided in two groups on the basis of treatment received at baseline (systemic thrombolysis vs mechanical thrombectomy alone). For imaging data, as a main explanatory variable, we will use BBB disruption values. For biomarkers data, as a main explanatory variable, we will use single patient’s relative prethrombolysis and post-thrombolysis variation (Δ median value) of biomarker levels, calculated according to the formula: (24 hours post-tissue Plasminogen Activator biomarker levels–pre-tPA biomarker levels)/pre-tPA biomarker levels.6 Differences in these Δ values will be analysed in relation to demographic and clinical features and across subgroups of patients with different outcomes. The net effect of each biomarker (baseline, 24 hours and Δ values) on outcomes will be also estimated by both logistic regression and ordinal models, including potentially confounding covariates, such as age, sex, baseline stroke severity and onset-to-treatment time.

Data monitoring body

Data are currently registered in the web-based registry available at http://www.stroketeam.it/risks/. Quality controls are done on a weekly basis. Imaging data are instantly checked for protocol conformity. Biosamples are processed using standard and harmonised operating procedures.

Sample size

We plan to include 140 patients. The sample size was calculated using observational data from a pilot study conducted in 32 patients who had a similar stroke by our group.19 Permeability values above the threshold within the ischaemic core were found in 38% of patients who had a stroke. Considering a statistical power of 0.80 (alpha error of 0.05), we estimated a sample size of 140 patients to demonstrate an effect of significant BBB disruption on relevant HT in at least 22% of patients.

Enrolment started on October 2015 and is ongoing. Using a definite protocol, a prospective collection of data and an adequate number of patients, this study will integrate clinical information about biological factors involved in reperfusion injury after cerebral ischaemia.

Patient and public involvement

Patient and Public Involvement in the development of the research question, in outcome measures and in the design of this study could not be planned. Results will be disseminated through patient’s association.

Discussion

Circulating and neuroimaging biomarkers of reperfusion injury measured in the acute ischaemic stroke setting represent potentially useful predictors of undesirable complications after recanalisation procedure. On the basis of the results of three small studies, CTP seems to have high sensitivity and specificity to predict HT after acute ischaemic stroke.20–22 MRI data from 41 patients evaluated for acute stroke have shown an association between BBB disruption at 24 hours (defined as gadolinium enhancement of CSF on fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) MRI) and baseline levels of MMP9.9 In a larger cohort of 180 patients who had an acute stroke, T2 FLAIR hyperintensities, possible expression of vasogenic oedema in the setting of BBB disruption, turned out to be associated with both baseline MMP-9 level and risk of haemorrhage.10

The RISKS combines advanced neuroimaging techniques for the study of BBB disruption with analyses of circulating biomarkers as potential predictors of reperfusion injury after acute phase interventions. The following considerations motivate this study: (1) in the human setting, the biological mechanisms of reperfusion injury remain incompletely described and understood; (2) a better knowledge of the underlying mechanisms may help discriminating patients at risk for complications from those who may definitely benefit from targeted interventions; (3) the validation of surrogate diagnostic markers of reperfusion damage such as BBB disruption may help designing and conducting clinical trials testing effectiveness of reperfusion injury antagonists.

Results of a pilot study conducted by our group19 and the successful enrolment of our first 100 patients may corroborate applicability and feasibility of our study protocol.

Ethics and dissemination

Informed consent is obtained by each patient before enrolment. A full explanation of the study, a written ‘Patient Information Sheet’ (detailing rationale, design and personal implications of trial entry) and informed consent form is provided. The consent process is deferred when the participant lacks the capacity to provide consent. Researchers interested in testing hypotheses with the data are encouraged to contact the corresponding author. Results from the study will be disseminated at national and international conferences and in MD and PhD medical theses.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Maria Elena Della Santa for her assistance in preparing the manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: DI, MN, VP, PN, FA and BP conceived the study and its design, managed its coordination, drafted the manuscript, developed the methodology, conducted collection, extraction and analysis of the data. BG, AMG, DG, MM, EF, SM, SN, FG, GP, AF, PP, SV, SG, CS, ML, AP, FP, AS and LP participated in the design of the study, and all authors critically revised the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This work is supported by Italian Ministry of Health grant number: RF-2011-02348240.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Azienda Ospedaliero Universitaria Careggi (Università degli Studi di Firenze) Ethics Committee (Prot. 2015/0015162 Rif. 138/12).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Khatri R, McKinney AM, Swenson B, et al. Blood-brain barrier, reperfusion injury, and hemorrhagic transformation in acute ischemic stroke. Neurology 2012;79:S52–7. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182697e70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bai J, Lyden PD. Revisiting cerebral postischemic reperfusion injury: new insights in understanding reperfusion failure, hemorrhage, and edema. Int J Stroke 2015;10:143–52. 10.1111/ijs.12434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Warach S, Latour LL. Evidence of reperfusion injury, exacerbated by thrombolytic therapy, in human focal brain ischemia using a novel imaging marker of early blood-brain barrier disruption. Stroke 2004;35:2659–61. 10.1161/01.STR.0000144051.32131.09 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Donahue J, Wintermark M. Perfusion CT and acute stroke imaging: foundations, applications, and literature review. J Neuroradiol 2015;42:21–9. 10.1016/j.neurad.2014.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Suzuki Y, Nagai N, Umemura K. A review of the mechanisms of blood-brain barrier permeability by tissue-type plasminogen activator treatment for cerebral ischemia. Front Cell Neurosci 2016;10:2 10.3389/fncel.2016.00002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Inzitari D, Giusti B, Nencini P, et al. MMP9 variation after thrombolysis is associated with hemorrhagic transformation of lesion and death. Stroke 2013;44:2901–3. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.002274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Turner RJ, Sharp FR. Implications of MMP9 for Blood brain barrier disruption and hemorrhagic transformation following ischemic stroke. Front Cell Neurosci 2016;10:56 10.3389/fncel.2016.00056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Piccardi B, Palumbo V, Nesi M, et al. Unbalanced Metalloproteinase-9 and Tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases ratios predict hemorrhagic transformation of lesion in ischemic stroke patients treated with thrombolysis: results from the MAGIC study. Front Neurol 2015;6:121 10.3389/fneur.2015.00121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Barr TL, Latour LL, Lee KY, et al. Blood-brain barrier disruption in humans is independently associated with increased matrix metalloproteinase-9. Stroke 2010;41:e123–8. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.570515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jha R, Battey TW, Pham L, et al. Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery hyperintensity correlates with matrix metalloproteinase-9 level and hemorrhagic transformation in acute ischemic stroke. Stroke 2014;45:1040–5. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.004627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Heldner MR, Zubler C, Mattle HP, et al. National Institutes of Health stroke scale score and vessel occlusion in 2152 patients with acute ischemic stroke. Stroke 2013;44:1153–7. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.000604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Larrue V, von Kummer R R, Müller A, et al. Risk factors for severe hemorrhagic transformation in ischemic stroke patients treated with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator: a secondary analysis of the European-Australasian Acute Stroke Study (ECASS II). Stroke 2001;32:438–41. 10.1161/01.STR.32.2.438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. SITS. Reducing the global burden of stroke: final study protocol. 2017. https://sitsinternational.org/

- 14. van Swieten JC, Hijdra A, Koudstaal PJ, et al. Grading white matter lesions on CT and MRI: a simple scale. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1990;53:1080–3. 10.1136/jnnp.53.12.1080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wardlaw JM, Smith EE, Biessels GJ, et al. STandards for ReportIng Vascular changes on nEuroimaging (STRIVE v1). Neuroimaging standards for research into small vessel disease and its contribution to ageing and neurodegeneration. Lancet Neurol 2013;12:822–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. IST-3 collaborative group. Association between brain imaging signs, early and late outcomes, and response to intravenous alteplase after acute ischaemic stroke in the third International Stroke Trial (IST-3): secondary analysis of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Neurol 2015;14:485–96. 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)00012-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Menon BK, d’Esterre CD, Qazi EM, et al. Multiphase CT Angiography: a new tool for the imaging triage of patients with acute ischemic stroke. Radiology 2015;275:510–20. 10.1148/radiol.15142256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tofts PS, Brix G, Buckley DL, et al. Estimating kinetic parameters from dynamic contrast-enhanced T(1)-weighted MRI of a diffusable tracer: standardized quantities and symbols. J Magn Reson Imaging 1999;10:223–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nannoni S, Gadda D, Piccardi B, et al. Quantitative measurement of blood brain barrier permeability on CT perfusion might predict hemorrhagic transformation after acute ischemic stroke. Abstract. ESOC 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hom J, Dankbaar JW, Soares BP, et al. Blood-brain barrier permeability assessed by perfusion CT predicts symptomatic hemorrhagic transformation and malignant edema in acute ischemic stroke. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2011;32:41–8. 10.3174/ajnr.A2244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Aviv RI, d’Esterre CD, Murphy BD, et al. Hemorrhagic transformation of ischemic stroke: prediction with CT perfusion. Radiology 2009;250:867–77. 10.1148/radiol.2503080257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lin K, Zink WE, Tsiouris AJ, et al. Risk assessment of hemorrhagic transformation of acute middle cerebral artery stroke using multimodal CT. J Neuroimaging 2012;22:160–6. 10.1111/j.1552-6569.2010.00562.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Turner RJ, Sharp FR. Implications of MMP9 for Blood Brain barrier disruption and hemorrhagic transformation following ischemic stroke. Front Cell Neurosci 2016;10:56 10.3389/fncel.2016.00056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. McColl BW, Rothwell NJ, Allan SM. Systemic inflammation alters the kinetics of cerebrovascular tight junction disruption after experimental stroke in mice. J Neurosci 2008;28:9451–62. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2674-08.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.