Abstract

Objective

To investigate the incidence of primary care presentations for herpes zoster (zoster) in a representative New Zealand population and to evaluate the utilisation of primary healthcare services following zoster diagnosis.

Design

A cross-sectional retrospective cohort study used a natural language processing software inference algorithm to identify general practice consultations for zoster by interrogating 22 million electronic medical record (EMR) transactions routinely recorded from January 2005 to December 2015. Data linking enabled analysis of the demographics of each case. The frequency of doctor visits was assessed prior to and after the first consultation diagnosing zoster to determine health service utilisation.

Setting

General practice, using EMRs from two primary health organisations located in the lower North Island, New Zealand.

Participants

Thirty-nine general practices consented interrogation of their EMRs to access deidentified records for all enrolled patients. Out-of-hours and practice nurse consultations were excluded.

Main outcome measures

The incidence of first and repeated zoster-related visits to the doctor across all age groups and associated patient demographics. To determine whether zoster affects workload in general practice.

Results

Overall, for 6 189 019 doctor consultations, the incidence of zoster was 48.6 per 10 000 patient-years (95% CI 47.6 to 49.6). Incidence increased from the age of 50 years to a peak rate of 128 per 10 000 in the age group of 80–90 years and was significantly higher in females than males (p<0.001). Over this 11-year period, incidence increased gradually, notably in those aged 80–85 years. Only 19% of patients had one or more follow-up zoster consultations within 12 months of a zoster index consultation. The frequency of consultations, for any reason, did not change between periods before and after the diagnosis.

Conclusions

Zoster consultations in general practice are rare, and the burden of these cases on overall general practice caseload is low.

Keywords: herpes zoster, primary care, virology, health informatics

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study used a novel and validated natural language processing software inference algorithm to identify herpes zoster (zoster) presentation rates and service utilisation using primary care electronic medical records over an 11-year period.

Despite a low frequency of zoster cases, the large data set enabled analysis of rates of zoster incidence by age bands and different demographics across the whole time period.

The algorithm was designed to maximise specificity and accuracy, thereby generating a conservative estimate of the burden of zoster presentations in primary care by keeping false positives to a minimum.

The gold standard for this study was based on doctor decision making, and the algorithm is limited by the quantity and detail of the recorded information in each consultation. Details of the reason for each visit, such as specific zoster complications, were not determined, just that the visit was identified as zoster related.

This study analysed normal hours primary care general practitioner consultations. The exclusion of nurse-only and out-of-hours consultations may result in an underestimation of primary care rates.

Introduction

Infection with varicella zoster virus (VZV) establishes lifelong persistence in sensory nerve ganglia. When the immune system is unable to maintain the suppression of the virus, it manifests as a clinical syndrome known as herpes zoster (zoster; shingles).1 About one-third of the population experiences zoster, with greater incidence in older age groups.2 The major risk factor for zoster is a decline in VZV immunity as cell-mediated immunity wanes with age.3 4 Cohort studies, from at least 22 countries, give incidence of zoster in the general population from 3 to 5 per 1000 person-years,5–10 and a lifetime incidence of 20%–30%.2 Much higher incidence is reported in older adults, increasing from 50 to 60 years of age, and ranging from 8 to 12 per 1000 person-years.2 7 Around half of the zoster cases >70 years of age will develop postherpetic neuralgia (PHN).11 The main rationale for the use of a zoster vaccine is to prevent the long-lasting effects of PHN. A live attenuated zoster vaccine is internationally available for adults over the age of 50 years and is on the national schedule in some countries, notably, the UK and Australia at the age of 70 years, and recommended in the USA from age 60 years.1

Several studies have reported increasing incidence rates over time across all age groups,6 in countries both with12–14 and without childhood varicella immunisation programmes.2 15 16 WHO recommends, when considering the optimal age and dosing schedule for zoster vaccines, that countries should take into consideration the age-dependent burden of disease, vaccine effectiveness, duration of protection and cost effectiveness of the vaccine.17 While there is a body of research around zoster and the burden of zoster disease, this is almost exclusively based on observational studies from administrative databases or health records, which will underestimate cases not coming to medical attention.6 Decisions around vaccination strategies for countries remain hindered by a more complete understanding of the burden of the disease for a population.

The objective of this study was to interrogate data from general practice electronic medical records (EMRs) to identify zoster-related primary care presentations and service utilisation associated with consultations for zoster-related conditions. Previous studies have shown the potential of using a novel software algorithm to enable the exploration of consultation notes in EMR systems used commonly for the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development primary care records.18 To date this software has shown the ability to analyse service utilisation for H1N1 influenza and childhood respiratory diseases while eliminating reliance on clinical coding.19 20

Methods

A natural language processing (NLP) software inference algorithm was developed to interrogate quantitative and qualitative cross-sectional and retrospective cohort data from EMRs.

Setting and participants

The development of the algorithm methodology has been earlier described.18 New Zealand has universal enrolment of the population with a primary care (general) practice and universal computerised recording of general practice doctor consultations. The study was conducted in the lower North Island in a mixed urban and rural setting. It consisted of 39 consenting general practices from two primary health organisations (PHOs) giving a total unique enrolled population of 391 000 over the study period between 1 January 2005 to 31 December 2015. This included individuals who both joined and left the cohort during this period. The cohort totalled 2 366 870.5 person-years and contained >22 million medical record transactions representing 6 189 019 doctor consultations.

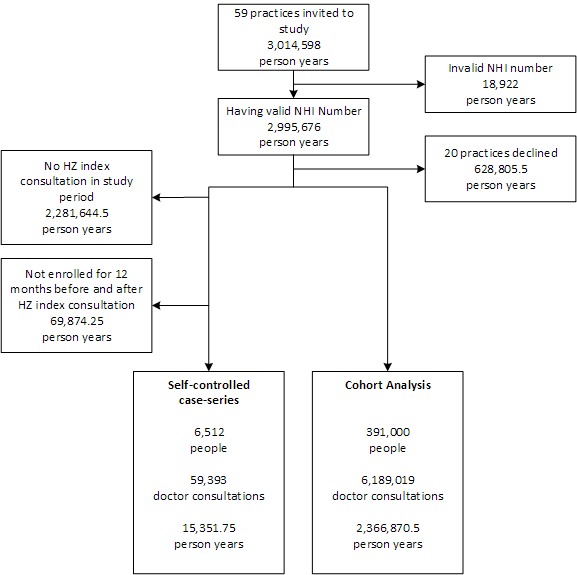

Figure 1 shows the selection process and steps taken through the development and analysis of the data set. Data were extracted directly from the EMR using software that automates the collection and secure transmission of large data sets. The complete data set was filtered to identify doctor consultations generated during standard office hours. Practice nurse and out-of-hours consultations were excluded. Each consultation record was linked to the individual’s unique National Health Index number. This individual unique identifier is assigned to every person who uses health services in New Zealand to enable records to be matched between data sets. All data were analysed on the premises of the PHO using rigorous protocols to ensure patient confidentiality, and no member of the research team accessed identifiable data. Rates were age-standardised, where appropriate, using the direct method and exact CIs were calculated.21

Figure 1.

Recruitment process. HZ - Herpes zoster; NHI - National Health Index.

Patient and public involvement

This retrospective observational study on general practice doctor notes did not directly involve patients.

Process

The software algorithm was designed to replicate the diagnosis and assessment made by clinical experts.18 It was trained, validated and tested using three independent data sets of 800 doctor consultation records. Each data set was stratified to contain 600 randomly chosen records and a further 200 random records from all that contained a simple keyword related to zoster. Clinical records from any single practice or provider could only exist in a single data set so as to avoid any training bias during validation or test procedures. Each record in all data sets was independently classified by two general practice clinical experts (LMB and AD). At the completion of coding all records, the clinical experts reviewed, discussed and reached consensus on any records where they showed a discrepancy in coding. The focus of algorithm development was to maximise specificity and positive predictive values (PPVs) to reduce false positives because of the expected relative rarity of zoster consultations.

A zoster index consultation was defined as the initial zoster consultation occurring for an individual within the past 12 months. A follow-up visit was any visit identified as related to zoster occurring within 12 months of any prior zoster consultation.

Analysis

The demographic characteristics of the study cohort was measured by age, gender, patient-identified ethnicity and socioeconomic deprivation quintile via the New Zealand Deprivation Index (a small census-area measure of socioeconomic deprivation).22 23 These were compared with those of all patients enrolled with the PHO (n=3 014 598 person-years) and the 2013 New Zealand Census data (n=4 353 198 people). Patients were observed for the period they were enrolled in a participating practice over the study period. In order to maintain a consistency of analysis across the study period, both deprivation and ethnicity were determined from the most recently recorded information available for each patient. Where appropriate, consultation rates were adjusted for algorithm sensitivity, specificity and age-adjusted for the 2013 New Zealand Census population using direct standardisation. All data aggregation, transformation, cleaning and storage were done in Microsoft SQL Server, and statistical analysis was undertaken in R. CIs for crude rates were calculated using a bootstrap over 1000 replicate rounds with resampling. CIs on age-standardised rates were made using the method described by Fay and Feuer.21 Hypothesis tests were conducted using Fischer’s exact test for cohort analysis and the Wilcoxon signed-rank test for self-controlled case series.

Results

Study cohort demographics

The age and gender of the study cohort approximated the national census profile. There was a larger proportion of those aged 18–23 years in the local enrolled population than in the study cohort, which is likely to be due to self-exclusion of practices providing student health services to the universities within the catchment area. While the demographic characteristics of the study cohort closely matched those of the enrolled population for deprivation, due to the geocoding system used for deprivation, 6% of both the enrolled and study cohort populations with incorrectly documented address information were not allocated deprivation scores. The study cohort had a higher proportion of people in the least deprived socioeconomic quintile with a correspondingly lower proportion in the two most deprived. As compared with the enrolled population, the study cohort had fewer with Pacific Island ethnicity (3% vs 5%) and more ‘other’ ethnicities, which included New Zealand European and Asian (88% vs 86%).

Accuracy of herpes zoster identification

The natural language algorithm had a PPV of 0.82 (95% CI 0.72 to 0.92), specificity of 0.9998 (95% CI 0.9997 to 0.9999) and sensitivity of 0.84 (95% CI 0.74 to 0.92). This was more accurate than using keywords only (PPV 0.66, specificity 0.9994 and sensitivity 1.0) or using a single clinical expert (PPV 0.53, specificity 0.9991 and sensitivity 0.93).

Herpes zoster consultations

The overall age-adjusted apparent rate of zoster index consultations was 42.7 per 10 000 person-years observed (95% CI 41.9 to 43.5), with an estimated true rate of 48.6 (95% CI 47.6 to 49.6). There were 10 316 index consultations for zoster and 3060 zoster-related follow-up consultations. The apparent rate for zoster index consultations was 16.7 per 10 000 doctor consultations (95% CI 16.3 to 17.0) with an estimated true rate of 17.5 (95% CI 17.1 to 17.9). This was the equivalent to one in 571 doctor consultations.

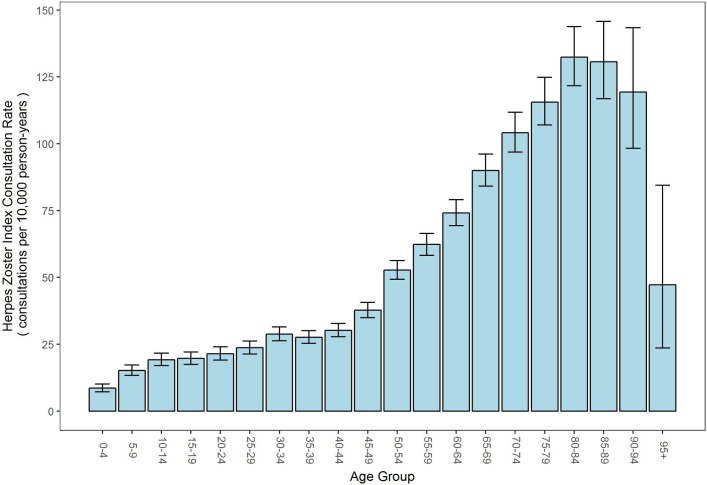

The rate of consultations were much higher in older age groups, as shown in figure 2, with the highest rate in the age group of 80–90 years at 128 consultations per 10 000 person-years.

Figure 2.

Herpes zoster index consultation rate by age group (bars represent 95% CIs).

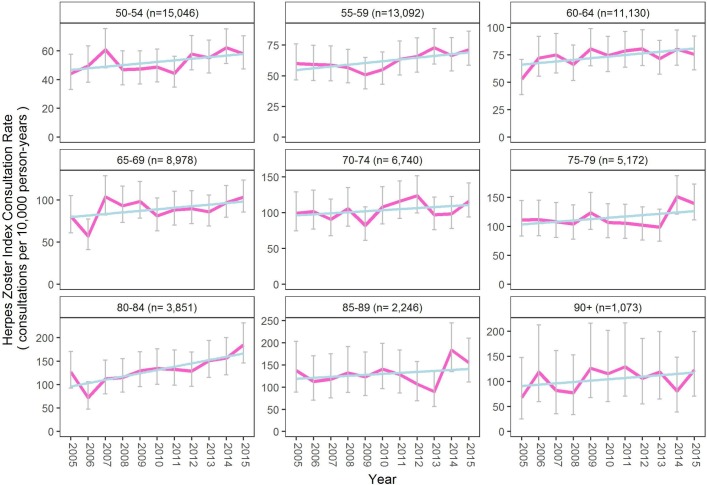

There was a significant increase in rate of zoster consultations over time (OR 0.86 (95% CI 0.78 to 0.94), p=0.0015). The rate of increase over time was particularly noticeable in the older age groups. This trend is shown in figure 3.

Figure 3.

Herpes zoster index consultation rate over time from age of 50 years, by 5-year age groups (n is mean patient-years per year, with 95% CIs and linear regression shown in blue).

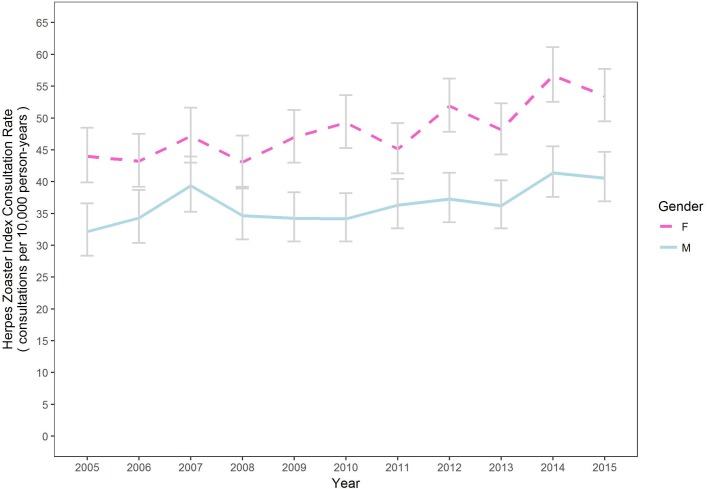

Gender

When comparing age-standardised data by gender, females experienced a statistically significant higher rate of zoster over the study period compared with males (F=48.3, M=36.6, p<0.001) as shown in figure 4.

Figure 4.

Herpes zoster consultation rate of index case over time by gender, age adjusted (95% CIs). F, female; M, male.

While the age-standardised rate of zoster increased over time generally, there was no statistically significant difference in the rate of increase between males or females.

Ethnicity and socioeconomic status

There were fewer index zoster consultations of those with Pacific Island ethnicity (age-adjusted rate 29.1 per 10 000 patient-years (95% CI 25.6 to 33.1), p<0.01) and Māori (New Zealand indigenous; rate 38.9 (36.3 to 41.6), p=0.019) than those from other ethnicities (rate 42.3 (41.4 to 43.2)). There was no significant difference in the rate of zoster index consultations across the different socioeconomic quintiles.

Health service utilisation

Herpes zoster-related consultations

Of the 10 316 zoster index consultations identified by the cohort analysis, most had no zoster follow-up consultations. Of these, 19% had a zoster follow-up consultation and only 5.8% consulted their doctor more than once in relation to zoster (table 1).

Table 1.

Distribution of follow-up consultations following zoster index cases

| Follow-ups | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| Total number | 8354 | 1365 | 372 | 100 | 73 | 16 | 14 | 8 | 2 | 6 | 2 | 3 | 1 |

| Percentage | 80.98 | 13.23 | 3.61 | 0.97 | 0.71 | 0.16 | 0.14 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.01 |

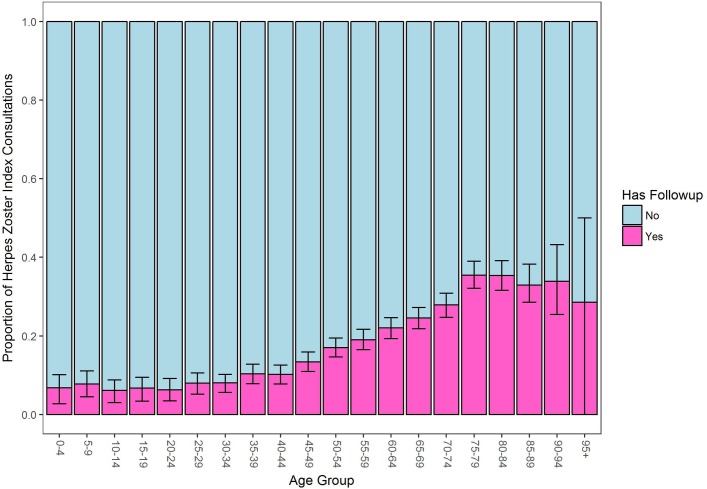

With increasing age, particularly from 45 years onwards, there was an increasing likelihood of follow-up consultations per episode as shown in figure 5.

Figure 5.

Proportion of herpes zoster consultations with or without follow-up visits by age group showing 95% CIs.

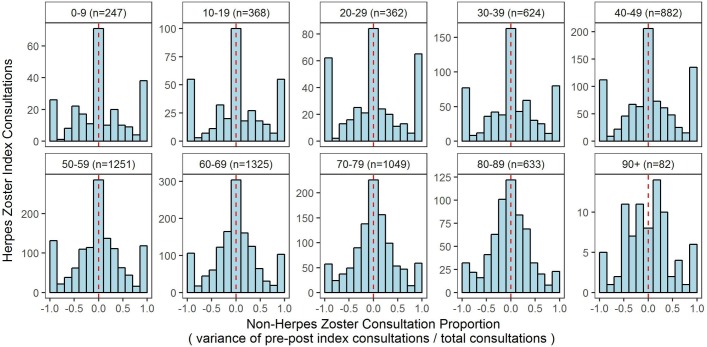

Distribution of non-herpes zoster consultations around index cases

To assess any correlation between zoster consultations and any changes in overall (non-zoster) consultations to general practice, we undertook a self-controlled case series analysis, consisting of 6823 of the zoster index cases, and measured the variance in the number of all non-zoster consultations for 12 months prior to and 12 months after each zoster index consultation occurred (a total of 27 months observation for each index consultation). This is expressed as the variance between the number of non-zoster consultations before and after the index consultation as a proportion of their sum. Positive proportions represented those with more consultations after the index consultation, while negative proportions represented those with more consultations before. Those with no consultations before or after were considered to have a proportion of zero as in figure 6. There were no statistically significant differences in the distributions at a threshold of 0.001.

Figure 6.

Distribution of overall consultation visits occurring prior to and after a herpes zoster index case by age group.

Discussion

Consistent with previously reported rates of incidence of zoster in primary care presentations, across many countries,5–8 10 this study found that the overall rate of incidence of zoster is 48.6 cases per 10 000 patient-years, with higher rates in the elderly7 and a 32% higher rate in females than males.9 The peak age of incidence seen in this study was in the age group 80–84 years, which is older than previously reported. An Australian study using Medicare Benefits Schedule items reported a peak age of 60–69 years.24 The importance of showing a peak at an older age is that it will affect modelling for decision making around the ideal age for zoster vaccine introduction.

Similar to other international findings, the overall incidence of zoster has increased from 2005 to 2016 across all age groups.6 New Zealand did not have a childhood varicella vaccination programme over this period, supporting previous commentary that this increase is unlikely to be related to a decline in circulating varicella virus.12

Previous literature has reported differences between ethnic groups, most notably, a reduced self-reported occurrence was seen in US blacks.25 Our New Zealand-based study reported a lower age-adjusted incidence for those of Pacific Island ethnicity at 29.1 per 10 000 patient-years (95% CI 25.6 to 33.1) and a rate of 38.9 per 10 000 patient-years (95% CI 36.3 to 41.6) for New Zealand indigenous Māori compared with other ethnicities. This is in contrast to almost all other important health statistics for older Pacific Island and Māori populations in New Zealand, for which there is a consistent equity gap, and poorer age-adjusted health outcomes are associated with these groups.26 There does not appear to be any socioeconomic link as there was no significant difference between different levels of socioeconomic deprivation. A different burden of childhood varicella seems unlikely because Māori are not a migrant group. This raises the question as to whether there are significant differences in rates across other ethnic groups internationally.

An important original finding from this study was the lack of evidence for increased burden of utilisation of health services at the primary care level. Using a large primary care data set over an 11-year period, we have demonstrated an equivalent of one zoster-related consultation in every 571 general practice consultations. Furthermore, the burden of subsequent consulting was very low with 80% of zoster-related presentations requiring no follow-up and 13% requiring only a single follow-up consultation. While there was an increasing likelihood of follow-up consultations following a zoster episode with increasing age, particularly from 45 years onwards, the burden on general practice consultation rates was not significantly affected, overall. An episode of zoster is reported to frequently reduce overall quality of health particularly in older age groups, most likely related to the prolonged effects of PHN.27 28 International literature reports hospitalisation in adults aged >50 years at a yearly rate of 28/100 000 zoster related hospitalisations as primary diagnosis (ranging from 6.1 in the age group 50–54 years to 95.8/100 000 persons in the age group >80 years).29 In New Zealand, during 2015 there were 361 hospitalisations with a primary diagnosis of zoster across all ages (Ministry of Health data). The burden of zoster admissions to hospital is severe when length of stay, cost and mortality are considered.30 However, our study has demonstrated that these complications are not translating through to increasing utilisation of general practice services. This indicates that overall burden on the primary care services is less than has previously been suggested, and that zoster contributes very little to the overall utilisation burden in general practice.

Study limitations

This study is specifically focused on the burden of zoster from the general practice perspective. As such, we are unable to comment on other aspects of the burden of zoster, such as patient quality-of-life measures, or the burden on the health service beyond the general practice, which includes the frequency of referrals to secondary healthcare services, hospitalisation and prescriptions.

The gold standard for this study was based on doctor decision making, and the algorithm is limited by the quantity and detail of the recorded information in each consultation. In particular, repeat consultations may under-report ongoing zoster-related symptoms when the primary reason for a visit is in relation to other comorbidities. We did not examine in detail the reason for the zoster-related visit to assess the incidence of zoster complications, such as PHN. However, this may not be a major concern as, for medico-legal reasons, significant clinical observations about ongoing zoster complications or progress are likely to be recorded. While recognising this, the overall incidence found in this study matches other international data, suggesting good concordance.

The number of less deprived individuals in the population studied was higher than that of the regional and national populations, but was otherwise well matched. Due to the self-exclusion of student health centres, the rate of zoster incidence in younger age groups may be under-reported, although it is unlikely to affect overall incidence rates since cases are predominantly in those aged >50 years. This study did not include out-of-hours presentations and patients not enrolled with a general practice. However, the main purpose of this study was to report on service utilisation burden in routine general practice, not periodic acute presentations in after-hours clinics. New Zealand has very high registration in general practice, particularly of the elderly population.31

Study strengths

In this study, a very large data set of doctor consultations were examined by the way of a software inference algorithm. This methodology interrogated the free-text EMRs of >6 million unique doctor consultations over an 11-year period. The large data set enabled analysis of rates of zoster incidence by age bands and different demographic measures, across the whole time period, despite the low frequency of zoster cases.

The strength of the NLP algorithm-based method used in our study is improved accuracy compared with the use of clinical codes or a simple keyword search, or review by a single clinical expert.19 32 This methodology, as opposed to a simple keyword search, is able to identify the context in which pertinent terms are being used in clinical narrative. For example, a keyword may be used by a clinician to express either the presence or absence of the disease, which impacts the specificity and PPV of that approach and ultimately overestimating disease. A single clinical expert is prone to make errors and has previously been shown to perform worse than a simple keyword search or NLP algorithm. In our study, two independent clinical coders reached concordance to provide a robust gold-standard comparison.

Using this NLP algorithm methodology, we have demonstrated its ability to review the burden of low-frequency conditions, such as zoster, in primary care, and follow changes in patterns over times with large numbers.

Unanswered questions and future research

This study only focused on burden at the primary care level. Future research is needed on the comparative burden of disease across the full spectrum of health services: community, primary care and hospital inpatient care. Further important questions include disaggregation of the burden of disease by comorbidities, the effect of the use of antivirals and other treatment modalities and why the rate of zoster is continuing to increase over time. In addition, studies internationally have shown significant burden of disease on the quality of life of individuals, particularly those with severe or prolonged disease complications.28 A qualitative study could provide insight into the effect shingles has on individuals and the potential value of a vaccine in reducing this burden. The low level of utilisation of general practice services suggests, however, that the burden of more severe disease falls on a small number of individuals and our results may prompt further discussion around modelling for whom to introduce zoster vaccines to in a population.

Conclusions

Overall, the rate of general practice doctor consultations related to zoster showed that this condition is rare in primary care and, while repeat visits following a zoster episode became increasingly common with age, the disease does not represent a significant burden on overall general practice workload. The peak age for consultations was older than has previously been reported, and there appear to be significant differences between ethnic groups, unrelated to socioeconomic circumstances. These are important findings particularly when considering the introduction of zoster vaccines across national immunisation schedules.

Use of a novel software algorithm to enable the exploration of consultation notes in EMRs is an efficient and effective way of identifying conditions, patterns, changes over time and the burden of disease on primary care services. We have also shown the methodology has the ability to review the burden of low-frequency conditions in primary care.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the primary care practices who consented to their consultation records being included in this study data set, and the primary health organisations who permitted the use of their proprietary software and resources.

Footnotes

Contributors: NMT, MLN and AD conceived the study. MHS and MLN managed the ethical approval and consent processes. AD, LMB and NMT provided clinical input into the algorithm design. JMR designed and built the natural language processing tools, programmed and trained the algorithm, and conducted the data analyses. AD and LMB classified the consultation records in the gold standard sets. NMT and MLN were the principal writers of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and revised the manuscript and approved its final version. All authors had full access to all of the data in the study and can take responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the analysis. All authors contributed to the development of the overall study methodology.

Funding: This work was supported by a New Zealand Lottery Health Research grant.

Disclaimer: The funding body had no role in the collection or analysis of data or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the University of Auckland Human Participants Ethics Committee Ref. 017617 on 25 July 2016.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. Eshleman E, Shahzad A, Cohrs RJ. Varicella zoster virus latency. Future Virol 2011;6:341–55. 10.2217/fvl.10.90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Brisson M, Edmunds WJ, Law B, et al. . Epidemiology of varicella zoster virus infection in Canada and the United Kingdom. Epidemiol Infect 2001;127:305–14. 10.1017/S0950268801005921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wehrhahn MC, Dwyer DE. Herpes zoster: epidemiology, clinical features, treatment and prevention. Aust Prescr 2012;35:143–7. 10.18773/austprescr.2012.067 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schmader K, Gnann JW, Watson CP, et al. . The epidemiological, clinical, and pathological rationale for the herpes zoster vaccine. J Infect Dis 2008;197 Suppl 2:S207–S215. 10.1086/522152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gauthier A, Breuer J, Carrington D, et al. . Epidemiology and cost of herpes zoster and post-herpetic neuralgia in the United Kingdom. Epidemiol Infect 2009;137:38–47. 10.1017/S0950268808000678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yawn BP, Gilden D. The global epidemiology of herpes zoster. Neurology 2013;81:928–30. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182a3516e [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kawai K, Gebremeskel BG, Acosta CJ. Systematic review of incidence and complications of herpes zoster: towards a global perspective. BMJ Open 2014;4:e004833 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-004833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pinchinat S, Cebrián-Cuenca AM, Bricout H, et al. . Similar herpes zoster incidence across Europe: results from a systematic literature review. BMC Infect Dis 2013;13:170 10.1186/1471-2334-13-170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yawn BP, Saddier P, Wollan PC, et al. . A population-based study of the incidence and complication rates of herpes zoster before zoster vaccine introduction Mayo Clinic Proceeding. 82: Mayo Clinic, 2007:1341–9. 10.4065/82.11.1341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Reid JS, Ah Wong B. Herpes zoster (shingles) at a large New Zealand general practice: incidence over 5 years. N Z Med J 2014;127:56–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Johnson RW. Herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia. Expert Rev Vaccines 2010;9:21–6. 10.1586/erv.10.30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hales CM, Harpaz R, Joesoef MR, et al. . Examination of links between herpes zoster incidence and childhood varicella vaccination. Ann Intern Med 2013;159:739–45. 10.7326/0003-4819-159-11-201312030-00006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jumaan AO, Yu O, Jackson LA, et al. . Incidence of herpes zoster, before and after varicella-vaccination-associated decreases in the incidence of varicella, 1992-2002. J Infect Dis 2005;191:2002–7. 10.1086/430325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Leung J, Harpaz R, Molinari NA, et al. . Herpes zoster incidence among insured persons in the United States, 1993-2006: evaluation of impact of varicella vaccination. Clin Infect Dis 2011;52:332–40. 10.1093/cid/ciq077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Toyama N, Shiraki K. Society of the Miyazaki Prefecture Dermatologists. Epidemiology of herpes zoster and its relationship to varicella in Japan: A 10-year survey of 48,388 herpes zoster cases in Miyazaki prefecture. J Med Virol 2009;81:2053–8. 10.1002/jmv.21599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Russell ML, Schopflocher DP, Svenson L, et al. . Secular trends in the epidemiology of shingles in Alberta. Epidemiol Infect 2007;135:908–13. 10.1017/S0950268807007893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Anon. Varicella and herpes zoster vaccines: WHO position paper, June 2014. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2014;89:265–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. MacRae J, Darlow B, McBain L, et al. . Accessing primary care Big Data: the development of a software algorithm to explore the rich content of consultation records. BMJ Open 2015;5:e008160 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. MacRae J, Love T, Baker MG, et al. . Identifying influenza-like illness presentation from unstructured general practice clinical narrative using a text classifier rule-based expert system versus a clinical expert. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2015;15:78 10.1186/s12911-015-0201-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dowell A, Darlow B, Macrae J, et al. . Childhood respiratory illness presentation and service utilisation in primary care: a six-year cohort study in Wellington, New Zealand, using natural language processing (NLP) software. BMJ Open 2017;7:e017146 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fay MP, Feuer EJ. Confidence intervals for directly standardized rates: a method based on the gamma distribution. Stat Med 1997;16:791–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Houghton F. Degrees of Deprivation in New Zealand — An Atlas of Socioeconomic Difference: By P. Crampton, C. Salmond, R. Kirkpatrick, R. Scarborough and C. Skelly. N Z Geog 2001;57:62 10.1111/j.1745-7939.2001.tb01602.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Salmond C, Crampton P, Sutton F. NZDep91: A New Zealand index of deprivation. Aust N Z J Public Health 1998;22:835–7. 10.1111/j.1467-842X.1998.tb01505.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Karki S, Newall AT, MacIntyre CR, et al. . Healthcare Resource Utilisation Associated with Herpes Zoster in a Prospective Cohort of Older Australian Adults. PLoS One 2016;11:e0160446 10.1371/journal.pone.0160446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Schmader K, George LK, Burchett BM, et al. . Racial differences in the occurrence of herpes zoster. J Infect Dis 1995;171:701–4. 10.1093/infdis/171.3.701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Anderson I, Crengle S, Kamaka ML, et al. . Indigenous health in Australia, New Zealand, and the Pacific. Lancet 2006;367:1775–85. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68773-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Serpell M, Gater A, Carroll S, et al. . Burden of post-herpetic neuralgia in a sample of UK residents aged 50 years or older: findings from the Zoster Quality of Life (ZQOL) study. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2014;12:92 10.1186/1477-7525-12-92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gater A, Abetz-Webb L, Carroll S, et al. . Burden of herpes zoster in the UK: findings from the zoster quality of life (ZQOL) study. BMC Infect Dis 2014;14:402 10.1186/1471-2334-14-402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Stein AN, Britt H, Harrison C, et al. . Herpes zoster burden of illness and health care resource utilisation in the Australian population aged 50 years and older. Vaccine 2009;27:520–9. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hobbelen PH, Stowe J, Amirthalingam G, et al. . The burden of hospitalisation for varicella and herpes zoster in England from 2004 to 2013. J Infect 2016;73:241–53. 10.1016/j.jinf.2016.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Enrolment in a primary health organisation. Ministry of health NZ. http://www.health.govt.nz/our-work/primary-health-care/about-primary-health-organisations/enrolment-primary-health-organisation (accessed 27 Oct 2017).

- 32. Wu MF, Yang YW, Lin WY, et al. . Varicella zoster virus infection among healthcare workers in Taiwan: seroprevalence and predictive value of history of varicella infection. J Hosp Infect 2012;80:162–7. 10.1016/j.jhin.2011.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.