Abstract

Introduction

Adults with lower levels of health literacy are less likely to engage in health-promoting behaviours. Our trial evaluates the impacts and outcomes of a mobile health-enhanced preventive intervention in primary care for people who are overweight or obese.

Methods and analysis

A two-arm pragmatic practice-level cluster randomised trial will be conducted in 40 practices in low socioeconomic areas in Sydney and Adelaide, Australia. Forty patients aged 40–70 years with a body mass index ≥28 kg/m2 will be enrolled per practice. The HeLP-general practitioner (GP) intervention includes a practice-level quality improvement intervention (medical record audit and feedback, staff training and practice facilitation visits) to support practices to implement the clinical intervention for patients. The clinical intervention involves a health check visit with a practice nurse based on the 5As framework (assess, advise, agree, assist and arrange), the use of a purpose-built patient-facing app, my snapp, and referral for telephone coaching. The primary outcomes are change in health literacy, lifestyle behaviours, weight, waist circumference and blood pressure. The study will also evaluate changes in quality of life and health service use to determine the cost-effectiveness of the intervention and examine the experiences of practices in implementing the programme.

Ethics and dissemination

The study has been approved by the University of New South Wales (UNSW) Human Research Ethics Committee (HC17474) and ratified by the University of Adelaide Human Research Ethics committee. There are no restrictions on publication, and findings of the study will be made available to the public via the Centre for Primary Health Care and Equity website and through conference presentations and research publications. Deidentified data and meta-data will be stored in a repository at UNSW and made available subject to ethics committee approval.

Trial Registration number

ACTRN12617001508369; Pre-results.

Keywords: overweight, obesity, primary care, preventive medicine, health literacy, m-health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is a large prospectively registered cluster randomised controlled trial.

Health economic evaluation will be based on linked health service data and costing of intervention.

While the cluster design prevents contamination between intervention and control groups, it means that both providers and patients will not be blinded to the intervention.

The study will be conducted in urban practices in two Australian states. This may limit its generalisability to rural settings and other countries.

Introduction

Rationale

Reducing the burden of chronic disease is an important public health priority in Australia.1 Overweight and obesity account for 7% of the burden of disease2 as a risk factor for 11 types of cancer, 3 cardiovascular conditions, chronic kidney disease, diabetes, dementia, gallbladder disease, fatty liver, gout, back pain and osteoarthritis.2 Currently, around 63% of the Australian population are overweight or obese (body mass index (BMI) 25 kg/m2 or more) and the prevalence is increasing.3 The burden of overweight is unequally distributed with a 13% higher prevalence of overweight in the lowest compared with the highest socioeconomic group in women.4 There is an urgent need to find effective strategies at both the population and individual level to prevent and manage this condition.

Low functional health literacy (ie, health-related reading and numeracy) is present in approximately 59% of the population and is more common in socioeconomically disadvantaged populations.5 It is a potential barrier to the uptake and effectiveness of a range of preventive interventions.6 Aspects of health literacy have also been associated with poorer uptake of screening programmes and immunisation.7 8 Conversely, higher health literacy has been associated with greater improvements in response to physical activity interventions in disadvantaged populations.9 Patients with low health literacy are less likely to engage in health-promoting behaviours,10–12 receive and understand preventive advice, and attend or complete programmes that they are referred to.13 14 A systematic review of interventions in primary care to improve health literacy for chronic disease behavioural risk factors found that interventions with multiple components were more effective at improving nutritional health literacy.15

Primary care is well positioned to contribute to the prevention and management of overweight and obesity. Over 86% of the population of Australia visit a general practitioner (GP) at least once a year.16 Almost one-third of patients presenting in general practice are obese and two-thirds are overweight or obese, which are rates similar to the prevalence in the general community.17 Behavioural interventions in primary care have been demonstrated to achieve a 5%–7% improvement in weight, blood pressure (BP) or lipids for patients, potentially preventing or delaying the onset of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease.18–20 However, these interventions tend to have lower uptake by low socioeconomic groups21 22 and, overall, most weight loss interventions in primary care achieve only small reductions in weight.23

Preliminary work leading up to this study

Over the past decade we have sought to develop more effective interventions to prevent disease in primary care which target disadvantaged populations who are more likely to have low health literacy. In previous research we have found that ethnicity and language interact with health literacy to influence the uptake of preventive interventions especially those for weight loss.24 This accords with the findings of others that health literacy differentials are greater among older people, for those born overseas, those who do not speak English at home and those with low educational attainment.25 In these groups, patient–provider communication tends to be less effective, leading providers to incorrectly assume that patients with low health literacy are poorly motivated and they are therefore less likely to offer lifestyle interventions.26 27 Organisational and practitioner barriers also contribute to low frequency and effectiveness of assessment, advice, goal setting and referral of patients with low health literacy.6 28 These barriers include time available for consultations and competing demands on primary care staff.

We have also identified a need to tailor prevention and management of excess weight to a patients’ level of health literacy.29 Our review of primary healthcare level interventions targeting health literacy around weight loss found limited information as to the effect of weight loss interventions on health literacy primarily because this is an outcome not frequently reported.30 We have evaluated a structured, nurse delivered health check intervention based on 5As that includes a brief assessment of health literacy, tailoring advice and the use of ‘teach-back’; goal setting that involves specific, time-bound goals that are set collaboratively and involve feedback; and assisted navigation to referral services and proactive follow-up visits.30–33 This has proven feasible to implement34; however, consistent with other studies, the impact on risk behaviours and weight have been small.23 This may be due to the limited capacity within primary care to provide interventions based on evidence that are of sufficient intensity and length.

We have concluded that there is a need to supplement weight management consultations in primary care with specific components that continue to operate outside the consultation such as coaching programmes and other support services. There is some evidence of barriers to uptake of these components such as cost and accessibility,27 35 although the evidence for health coaching suggests it is an accessible, affordable and effective method to change health behaviours.36 37 Moreover, an evaluation of a government-funded telephone coaching service in New South Wales (NSW) suggested that it could be effective in reaching disadvantaged population groups.38 Another promising approach is the use of eHealth to supplement both clinical care and referral programmes in supporting behavioural change. Previous research has demonstrated the effectiveness of mobile health (m-health) text messages as part of a lifestyle programme to prevent unhealthy weight gain in young adults.39 This adds to the emerging evidence of the efficacy of using mobile apps and SMS text messaging in supporting change in health behaviours.40 However, the optimal form and role of this technology for patients with low health or eHealth literacy is still unclear.

This paper describes the protocol for the development and evaluation of an intervention which combines face-to-face consultation in general practice with these digital health approaches based on previous research which has demonstrated both feasibility of implementation and highlighted the potential for health gains.

Intervention development

The various components of the HeLP-GP intervention have been developed and piloted over the past 5 years.

The brief primary care intervention which is designed to support practices to improve the quality of preventive care for the SNAP (smoking, nutrition, alcohol and physical activity) risk behaviours and weight management is based on behavioural theory and is structured on the 5As framework which encompasses assessment, advice, agreeing on goals, assisting with motivational counselling and referral options and arranging follow-up.13 41 Progress along the pathway from assessment to follow-up is associated with increased patient motivation and behavioural change.42 This has been trialled in general practice and found to be feasible and acceptable and to lead to improvement in the quality of preventive care.30 43 44 This intervention was adapted for use by practice nurses (PNs) and modified for patients with low health literacy to include brief screening for low health literacy, tailored communication and referral navigation to local lifestyle programmes and piloted.45 It was subsequently evaluated in a trial which demonstrated its feasibility and acceptability to providers and patients.30

The app used in this study is supported by Healthy.me, a personally controlled health management platform designed to help patients and consumers manage their health.46 This has been shown to improve uptake of preventive services,47 48 and strong consumer acceptance has been demonstrated in Australia across different healthcare settings including primary care.49 This platform was modified to create the mobile application used in this study (my snapp). This was informed by research that interventions based on theory and those involving goal setting and self-monitoring as well as providing additional methods to interact with patients, particularly text messages, were more effective.50–53 Other research suggests that patients with low health literacy prefer apps or text messages to other sources of online information.54

Aims and research questions

The aim of this study is to evaluate the implementation and effectiveness of a preventive intervention in primary care structured around the 5As framework supported by a patient-facing mobile app, consultations with the PN and/or referral to a telephone coaching service. The intervention aims to develop the knowledge and skills of overweight or obese patients with low health literacy. The trial will assess the impact of the intervention on preventive care received, patients’ health and eHealth literacy, physical and behavioural risk factors, quality of life and costs.

Description of the intervention

The HeLP-GP intervention includes a practice-level quality improvement intervention and a clinical intervention. A logic model for the intervention can be found in online supplementary appendix 1.

bmjopen-2018-023239supp001.pdf (66.2KB, pdf)

Practice intervention

This includes a deidentified medical record audit, training of practice staff (GPs and PNs) and a series of three practice facilitation visits.

Medical record audit

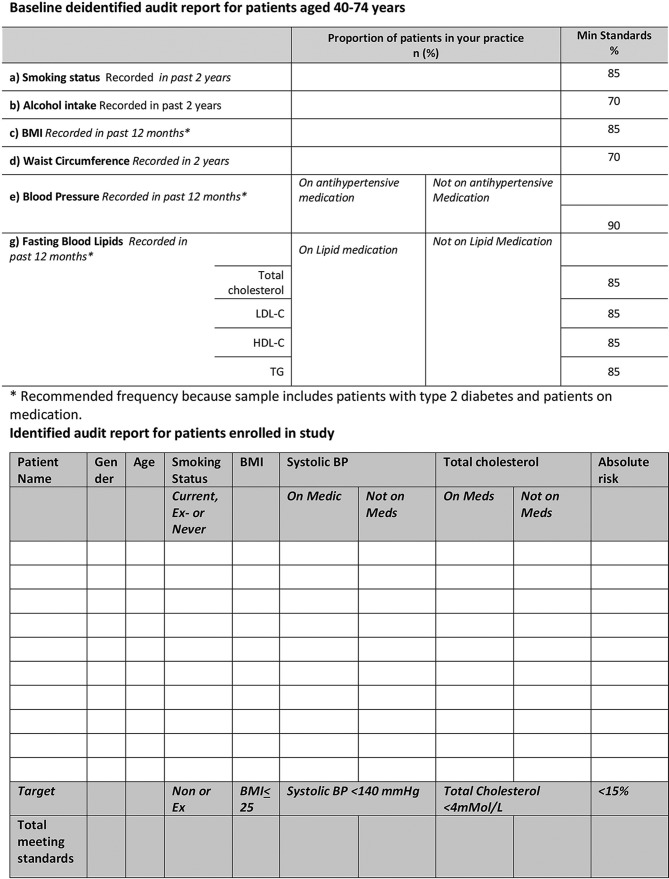

A deidentified medical record audit will be conducted by research staff using the DCP programme prebaseline in both intervention and control patients aged 40–74 years (who have not had a heart attack or stroke or do not have diabetes requiring insulin), on the recording of smoking status, alcohol consumption, BMI, waist circumference (WC), BP and total cholesterol. In intervention practices, an identified medical audit of the records of consenting patients participating in the trial will be conducted at baseline and 12 months. This will include assessing the control of their risk factors and cardiovascular risk. Audit reports will be fed back to practitioners (GPs and PNs), who will reflect on the reports and be supported to make improvements in the practice facilitation visits (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Clinical audit reports. BMI, body mass index, BP, blood pressure; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; Meds, medications; TG, triglyceride.

GP and nurse training to deliver intervention

Three comprehensive online training modules will cover study processes, the health risks of obesity, benefits of weight loss, the role of GPs and nurses in weight management, the components of the HeLP-GP intervention, tailoring care to the needs of people with low health literacy, processes to be followed for the health check visits and the use of the app with patients. Online videos will reinforce the GPs’ and PNs’ use of the app and referral to telephone coaching. Links to these will be provided to participating GPs and PNs. An online post-training questionnaire and evaluation form will be completed by GP and PN participants and will provide information to evaluate the training and its impact.

Facilitation visits conducted by chief investigators and primary health networks

Facilitation visits will be made up to three times over 3 months to each intervention practice during the beginning of intervention phase to support PNs and the practice. The aim of the practice facilitation is to support each intervention practice to implement the HeLP-GP intervention including making improvements in recording based on the initial deidentified clinical audit and prepare for the health check visits.

Clinical intervention

The clinical intervention has three components, each of which will be offered to all patients in the intervention group: (1) a health check visit with the PN, (2) a patient-facing app—my snapp and (3) referral to telephone coaching. Patients may receive any concomitant care indicated for their medical conditions.

PN health check and follow-up

Eligible patients will attend a health check visit with the PN within 4 weeks of recruitment. The content of the nurse consult is based on the 5As (table 1). The content of the consultation is consistent with the Australian Guidelines for the management of overweight and obesity and will include assessment of health literacy, brief advice, use of ‘teachback’ to determine if the patient has understood the advice given, goal setting (using my snapp or recorded using a health check form) and offering referral to telephone coaching (Get Healthy). The nurse will be alerted to those patients who have low eHealth literacy (from the baseline assessment) and will spend extra time demonstrating and checking the use of my snapp (over one or two consultations). Patients will be reviewed by the PN at 6 weeks and by the GP at 12 weeks.

Table 1.

Initial practice nurse health check (40 min)

| Assess | Review baseline body mass index, waist circumference, blood pressure and lipids. Briefly assess diet, physical activity, health literacy and eHealth literacy. |

| Advise/Agree | Provide brief advice on risk factors and health behaviours, checking understanding using the Teach-back method. Register patient for the app. Download and log into the app using the patients phone. Work with patient to enter profile and set relevant lifestyle goals in the app. |

| Assist | Introduce and provide referral to the Get Healthy telephone coaching programme to the patient (outline purpose of the programme and details about participation). |

| Arrange | Arrange follow-up visit at 6 weeks and a further visit with the general practitioner at 12 weeks. |

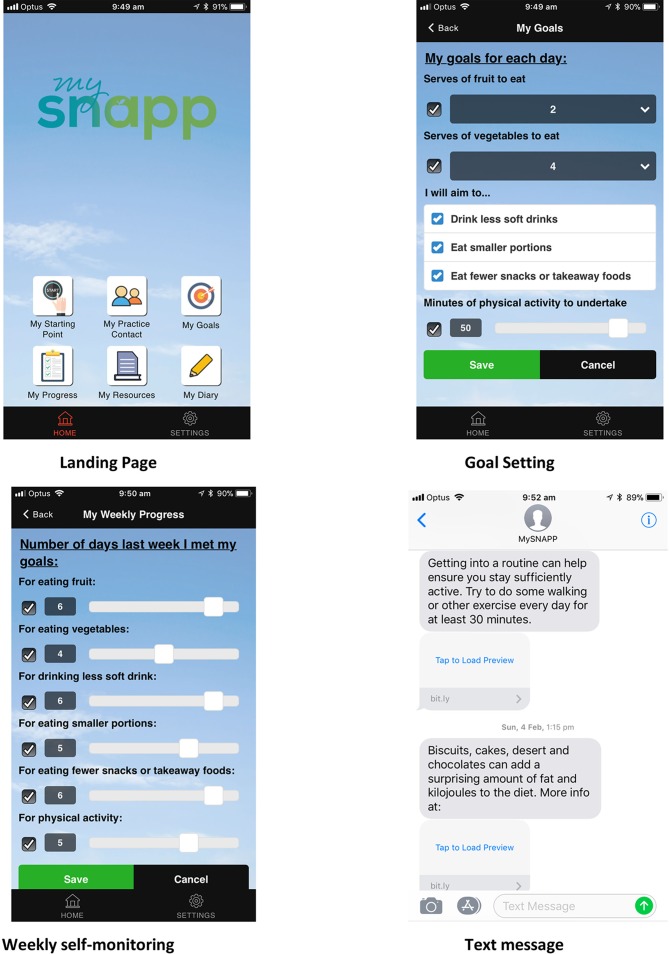

my snapp

The components of the app are described in table 2 and figure 2. The PN explains the app, supports the patient to register and download the app, enters information on risk factors (BMI, WC, BP) and the practice and helps the patient to set goals and navigate the app. There is also a patient website where participants can get further information and communicate any problems or issues with the app. The content of my snapp aligns with both the nurse health check and the telephone coaching (table 2).

Table 2.

my snapp content

| Section | Description |

| My starting point | Nurse records initial measurements (height, weight, waist circumference, blood pressure) during health check visit. |

| My practice contact | This records general practitioner and practice nurse’s contact details. |

| My goals | Nurse assists patient to set and revise diet and physical activity goals during health check visit and at 6-week follow-up. |

| My measures | Patient records achievement of goals and views graphs of progress over time in weeks in which they achieved goals for diet and physical activity. |

| My resources | Patient accesses fact sheets and videos about healthy eating and exercise. The fact sheets can be accessed in English or Arabic. |

| My diary | Patient keeps notes on progress and any problems for discussion with the nurse or general practitioner. |

| Text messages | Two text messages (one focused on diet and one on physical activity) are sent from the app each week. These are tailored to week and provide direct advice and a web link for further information. |

Figure 2.

my snapp screens.

Telephone coaching

The telephone coaching programme recommended to patients is ‘Get Healthy’ which is supported by the relevant state government and provided free of charge. Get Healthy delivers 10 free coaching calls over 10 weeks which provide:

Review of lifestyle goals (diet and physical activity) and ways to address barriers to achieving these goals.

Practical health information.

Support and resources to promote self-monitoring of diet, physical activity and weight.

Resources and tools to develop and maintain motivation for a healthier lifestyle.

Assistance to deal with set-backs and problem solve.

Social support to help participants to try new ideas and approaches to address lifestyle behaviours.

The coaching is available in multiple languages with the assistance of the national interpreter service.

Assessing the implementation fidelity of the intervention

Implementation of the intervention will be assessed by the following measures:

Percentage of GPs and PNs who complete the online training modules.

Percentage of intervention patients who receive baseline and 6-week clinical review by a PN.

Percentage of patients who receive a health check at 12 weeks by a GP.

Usage of the lifestyle app determined by app-analytics (percentage of patients with documented goals related to lifestyle change).

Percentage who received assisted referral to Get Healthy telephone coaching.

Percentage of patients who take up and complete Get Healthy telephone coaching programme.

Methods and analysis

Trial design

The trial is a pragmatic, two-arm, practice-level cluster randomised controlled trial evaluating impacts and outcomes of a m-health-enhanced preventive intervention in primary care.

Setting

Australian general practice. The study will be conducted in two regions of Sydney (South West Sydney and Central and Eastern Sydney) and Adelaide, in collaboration with the local primary health networks (PHNs).

Randomisation

Randomisation of practices into intervention or control groups (providing usual care) will be performed using an internet-based randomisation service (RANDOMIZE.NET). Practice randomisation was chosen because of the risk of contamination if individual patients were randomised within practices. Randomisation will be performed in two waves. Practices will be stratified according to the size of the practice (less than five GPs and five or more GPs) and location (NSW/South Australia (SA)) prior to randomisation. GPs and PNs will be delivering the intervention and are not blinded to the intervention.

Eligibility and exclusion criteria

General practices

Eligibility for practices is based on meeting the following inclusion criteria. Practices should:

Be situated in local government areas with a low Socio-economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFAi) score equal to and below the sixth decile (usually associated with lower health literacy.5

Use clinical software compatible with the data extraction and recruitment tool Doctors Control Panel (DCP). This includes Medical Director, MediNet, PracSoft and Best Practice and associated compatible billing software (Pracsoft and Best Practice Management).

Agree to the installation of DCP for the purposes of clinical audit and to identify eligible patients for the study.

Have access to an active internet connection.

Have at least one PN who is prepared to conduct the HeLP-GP intervention with eligible and consenting patients and complete data management relating to these patients.

Agree to provide GP follow-up health checks to participating patients at 12 weeks and 12-month time points.

Can make their staff available to distribute study materials to potential study participants when they register with reception prior to seeing a GP.

Practice patients

Eligible patients are those who are:

Aged 40–74 years.

Overweight or obese (BMI ≥28 recorded in last 12 months).ii

With BP recorded in the clinical software within the previous 12 months.

Speaking English and/or Arabic. iii

With access to a smartphone or tablet device.

Exclusion criteria

Experiencing recent weight loss (>5% in past 3 months).

A diagnosis of diabetes requiring insulin or a current prescription for insulin.

A diagnosis of cardiovascular disease (includes angina, myocardial infarction, heart failure, heart valve disease (rheumatic or non-rheumatic), stroke (cerebrovascular accident)).

Taking medication for weight loss (Orlistat or phentermine).

Cognitive impairment.

Physical impairment which prohibits engaging in moderate-level physical activity.

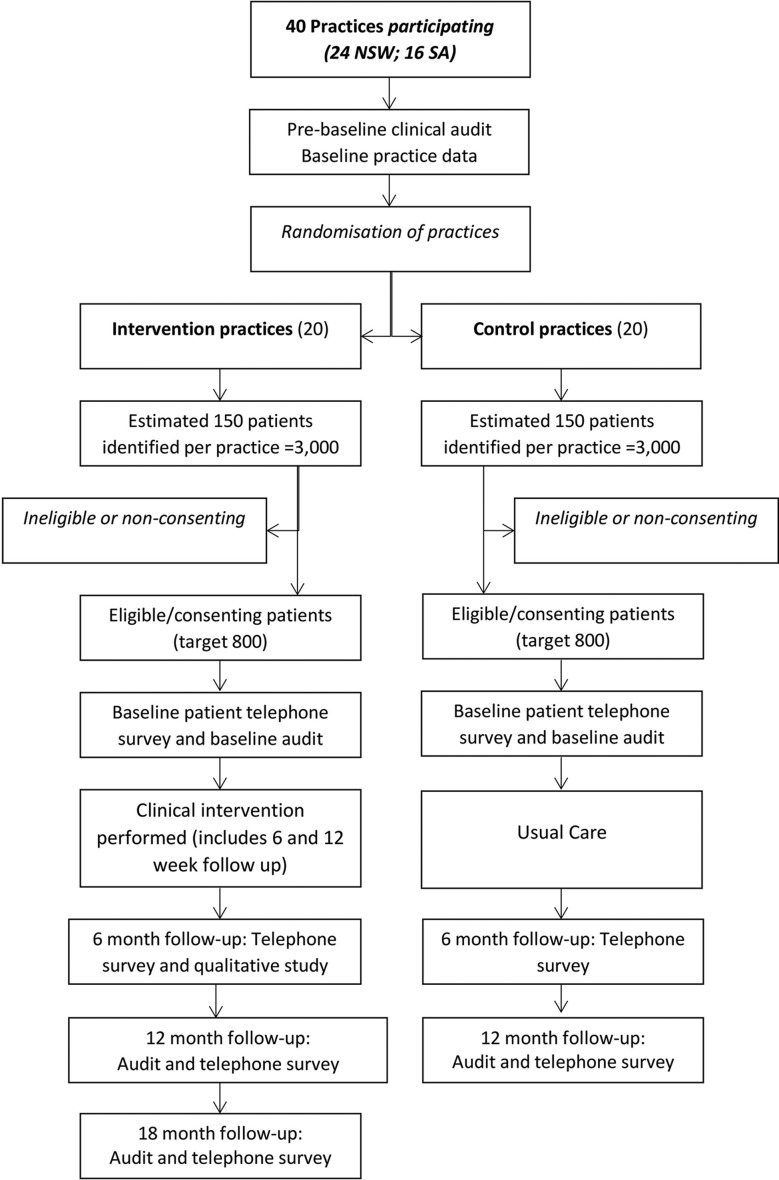

Recruitment

The recruitment process for practices and patients is outlined in figure 3. The target practice recruitment is 24 practices from two regions in Sydney (South West Sydney and Central and Eastern Sydney) and 16 practices from Adelaide, SA.

Figure 3.

Practice and patient recruitment. NSW, New South Wales; SA, South Australia.

The primary source of practice recruitment will be through participating PHNs in the target locations. PHNs will approach potentially eligible practices using mail, fax and practice visits to ascertain their interest. Practices will be provided with a study outline and asked to complete an Expression of Interest. A face-to-face practice visit will provide detailed information about practice tasks and confirm eligibility.

Recruitment of practice patients

Patients will be recruited at the point of presentation using the Doctors’ Control Panel software (DCP) which has also been used in previous research [34]. This software will be programmed according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria to identify potential participants as they present to the practice. These patients will be flagged and information on patients BMI, lipids and BP will be extracted from the medical record and printed. This information will be attached to information and consent forms by the practice receptionist and given to patients to read and discuss with the GP or PN. The practice will be reimbursed for the time spent by the reception staff.

Patient and public involvement

The development of the research question and outcome measures was informed by previous research conducted in general practice on preventive care, health literacy and obesity management. This included extensive qualitative study with patients about their experience of care in general practice and the influence of their culture and health literacy.24 34 43 55 Patients were not involved in the design of this study and will not be involved in the recruitment to and conduct of the study. We will conduct qualitative interviews with participants on their experience of the intervention. A summary report will be made available to participants via the study website.

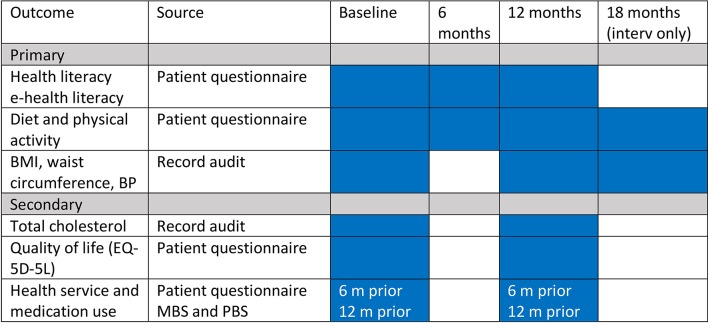

Outcomes

All primary outcomes are changes at the level of the individual patient. These include change in:

Domains of health literacy from the Health Literacy Questionnaire56 from self-report in telephone interviews between baseline, 6 and 12 months.

eHealth literacy assessed using the eHealth Literacy Scale (eHeals)57 from self-report in telephone interviews between baseline, 6, 12 and 18 months.

Biomedical risk factors (weight, height, BMI, WC, BP) through audit of clinical records, between baseline, 6, 12 and 18 months.

Secondary outcomes include change in:

Behavioural risk factors (daily fruit and vegetable consumption and physical activity level) assessed from self-report in telephone interviews between baseline and 6 months.58–60

Total cholesterol extracted from the medical record at baseline and 12 months.

Health-related quality of life measured using the EQ-5D-5L61 administered by telephone survey at baseline and 12 months.

Cost of intervention including service use assessed from linked data from public medical insurance (Medical Benefits Schedule (MBS), Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) and hospital data at 12 months.

- Receipt of advice given by the GP or PN30 assessed by patient interview at baseline and 6 months for:

- Smoking cessation

- Diet

- Physical activity

- Weight management.

Data collection

Practice

A practice assessment survey will be conducted by the research team at baseline to determine organisation and staffing, use of health education materials and links to other services.

Providers

GPs and PNs involved in the study will complete a questionnaire at baseline and 12 months. This will ask about their existing preventive practices and referral pattern, approach to and confidence with health literacy and health education, previous training and education.43 62

Patient surveys

All patients will participate in a survey administered by research staff by telephone at baseline, 6 and 12 months to assess diet and physical activity behaviours, health literacy and eHealth literacy. The interview will include questions about education received in general practice and referral for lifestyle or weight interventions at baseline and 6 months and quality of life at baseline and 12 months. Intervention group patients will be interviewed at 18 months about lifestyle behaviours.

Medical record audits

These will be conducted at baseline, 6 months, 12 months and 18 months.

Administrative health service data

All patients will be asked to consent to provision of health service and medication use from routinely collected data from Australia’s national health insurance and pharmaceutical benefits authorities (Medical Benefits Schedule (MBS) and PBS).

Qualitative interviews

A sample of up to 25 patients and 20 providers stratified by state and practice size will be interviewed between 3 and 6 months post intervention. The interviews will explore patient and provider perceptions of how preventive care is influenced by health literacy and provide feedback on the fidelity and barriers to the adoption of the intervention (figure 4).

Figure 4.

Outcomes and data collection. BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; MBS, Medical Benefits Schedule; PBS, Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme.

Data will be collected on all participants who discontinue or are excluded.

Control practices

After the initial audit of recording of risk factors, which will be fed back to control practices to improve recording, they will recruit patients in the same way as intervention practices. They will provide usual care (the clinical practice routinely offered to patients by the GP and PN). Data from patients attending control practices will be collected from their medical records at baseline and 12 months and they will receive the same telephone questionnaire as patients in the intervention group which includes the frequency of advice and referral at baseline and 12 months. Control practices will be offered the intervention after 12 months.

Sample size calculation

We aim to recruit 40 practices (24 NSW and 16 SA): 20 practices intervention and 20 practices control. We are aiming to consent 40 patients per practice (1600 total) based on previous research [44]. We anticipate a loss of approximately 20%–25% at follow-up (12 months). We will seek mobile numbers and alternative contacts to improve follow-up. Estimates for sample size based on intracluster correlation coefficients, prevalence, variance and effect sizes from our previous research are given in table 3, based on a two-sided test of significance at α=0.05, β=0.8% and 20% lost-to-follow-up [44] (table 3).

Table 3.

ICC and sample size estimates for primary outcomes

| Outcome | ICC | Design effect (30–40 patients per practice) |

Effect size or difference in proportions | Sample size per group |

| Mean Health Literacy Score | 0.014 | 1.43 | 0.4 | 140 |

| Mean Diet score | 0.001 | 1.03 | 0.21 | 367 |

| Mean Physical Activity score | 0.018 | 1.56 | 0.28 | 312 |

| Mean BMI | 0.042 | 2.30 | 0.30 | 401 |

| Mean systolic BP | 0.057 | 2.77 | 0.39 | 285 |

BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; ICC, intracluster correlation coefficient.

Data management

Data will be cleaned and coded and stored in a secure environment according to the data management protocol.

Adverse events

An independent adverse events committee will monitor and if necessary investigate any reports of possible adverse events or harms.

Analysis

We will examine differences in the change in the primary and secondary outcomes between intervention and control practices at 6 months for health literacy and patient behaviours and at 12 months for all outcomes. Analyses will be conducted on an intention-to-treat basis and adjusted for baseline differences in any characteristics (eg, age, gender) between groups. We will analyse outcome variables (health literacy, eHealth literacy, diet and physical activity behaviours, BMI, WC, BP, total cholesterol, quality of life and health service use) using multilevel linear and logistic regression techniques that adjust for clustering by practice with multiple imputation for missing values.

Economic evaluation

Information on resource use associated with the intervention will be collected by research staff, including the cost of setting up the intervention: practice staff education, practice support visits and materials and web support. Other relevant resource use includes GP and PN visits, referrals, hospital attendances and prescribing. We will request patient consent to access their medical records, MBS and PBS data, and public hospital data from the state health departments. The MBS, PBS and state data will capture most primary care and hospital costs. The cost of PN visits for health checks will be assigned an hourly rate based on PN salary levels plus on-costs. Questions on patient use of lifestyle services and programmes, and non-Medicare funded allied health will also be included in the patient questionnaire. Cost estimates will be generated for referrals to community-based programmes. In the base case analysis, undertaken from a health service perspective, referrals to allied health professionals will only be costed if supported by a Medicare claim. The incremental costs of the intervention will be presented alongside the consequences with respect to changes in quality of life (including the estimation of quality-adjusted life year gains informed by the EQ5D-5L) and differences in health literacy, behavioural outcomes and clinical measures (BMI, BP and lipids). Deterministic and bootstrapped sensitivity analyses will be undertaken to identify key uncertain parameters and represent uncertainty around the mean estimates, respectively.

Qualitative analysis

The qualitative interviews will be transcribed and analysed thematically using the program NVivo (QSR NVivo 11). This will use an inductive approach based on the data as well as deductively based on health literacy and health information theory.13 63

Ethics and dissemination

Practice and provider consent

Written consent will be obtained from all participating practices including consent to conduct the study in the practice and access practice data, and individual consent from all participating GPs and PNs.

Patient consent

Patients will be given information and consent forms in English or Arabic language and be able to ask further questions of the GP or PN. The patient will provide their written consent by filling in the consent form and either placing it in a collection box at reception or by returning it in a ‘reply paid’ envelope to the research team. To increase comprehension and meaningful consent within our target population of patients with low health literacy, we have shortened and simplified the Participant Information Statement and Consent forms. Patient eligibility will be confirmed by the GP and at subsequent interview. They will be invited by mail at 6 months to separately consent to the use of routinely collected data on health service use (from Medicare (MBS) Australia’s national health insurance programme), pharmaceutical use (from the PBS) and hospitalisation data (from state-admitted patient data collections).

Withdrawal

Practices or patients may withdraw from the study at any time. If patients commence weight loss medication or develop cognitive impairment or severe illness, they will be withdrawn from the study. Withdrawals and reasons for withdrawal will be recorded.

Data deposition

Data and meta-data will be stored in a repository at the University of New South Wales. Deidentified data will be made available subject to ethics committee approval.

Dissemination

The findings of the study will be made available to participants and the public via the Centre for Primary Health Care & Equity website and through conference presentations and research publications. There are no restrictions on publication.

Discussion

This trial evaluates a comprehensive intervention which is designed to support better preventive care for overweight and obese patients with low health literacy. It builds on previous work by the investigators and others to develop feasible interventions in primary care that address both patient and practice barriers to adoption, implementation and effectiveness. If successful, it will inform policy and practice including the role of primary care in addressing the challenge of overweight and obesity and the often-conflicting information that is available to practitioners and the public.

The complexity of the intervention and evaluation poses potential threats to internal and external validity. Recruiting and engaging a large number of practices to a trial such as this is becoming increasingly difficult. We have addressed this by working in partnership with PHNs (district level organisations of general practice and allied health services) to identify, approach and brief practice principals and practitioners on the study. Practice costs will be reimbursed, and practitioners will be able to access continuing professional development points through the clinical audit and training. However, the main incentive is the value of the research itself and how it will inform policy and practice in the long run and this needs to be carefully discussed.

Problems with recruitment, retention or engagement of patients with the intervention and data collection have the potential to reduce statistical power and therefore the ability to detect the primary outcomes with adequate precision. In this setting, recruitment procedures need to avoid pressure from the research team and patient’s own GP to ensure that eligible patients are approached and provided with sufficient information to make an informed decision about participation. We will work with practices to set up software and systems to make this possible. A significant part of the burden on participants will be from the telephone interviews by the research team. Although telephone interviews are preferred by most patients, they are onerous if they are too long. We have thus had to balance this burden against our desire to collect as much information as possible using robust instruments.

A further risk is that the clinical intervention will not be implemented in practice as we planned. Again, addressing this requires close work with the practices. The implementation measures and qualitative evaluation will provide some insight, but this may be too late to correct. We have thus built into the practice level intervention several measures to improve fidelity. These include feedback mechanisms in the online training, reflective feedback from practices on the audits and practice discussion during the facilitation visits. These will be tracked regularly during the implementation of the trial. A further risk is that some health and eHealth literacy will both be required for adoption of the app by patients and is expected to improve as a result of the intervention use. This will be addressed by the support provided to patients by PNs and GPs.

The fieldwork for the study is planned to be completed by mid 2019 with follow-up completed by late 2019. We anticipate circulation of the main findings from the study by 2020.

Trial sponsor

Centre for Primary Health Care and Equity, UNSW. Contact Professor Mark Harris +61 2 93858384 or m.f.harris@unsw.edu.au

Committees

The trial has a steering committee comprised on the project manager and investigators who oversees the project.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the partnership of the Central and Eastern, South West Sydney and Adelaide Primary Health Networks and the other HeLP-GP investigators and research staff especially An Tran in Sydney and Carmel McNamara in South Australia. We also thank Paige Martin, Jason Dalmazzo, Abir Khurshied, Rattapon Kevin Deeraviset for their efforts in the development of my snapp; staff in the New South Wales and South Australian Ministry of Health and Get-Healthy (especially Ruth Chesser-Hawkins, Lyndall Thomas and Kate Reid) for their support in providing access to the telephone coaching programme and collection of data associated with its use; and Anton Knieriemen, Colin Sheppard and Oliver Frank who developed a tailored version of the DCP program to facilitate patient recruitment and clinical audits. The authors also acknowledge the general practices involved in piloting for this for the project and the consumers linked to Adelaide PHN for piloting my snapp.

Footnotes

Australian Bureau of Statistics Socioeconomic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA) http://www.abs.gov.au/websitedbs/censushome.nsf/home/seifahelpansuis?opendocument&navpos=260

The cut-point for BMI was chosen to target people at higher risk and to capture people from Asian backgrounds who have a lower equivalent BMI.

Arabic was chosen as many recently arrived immigrants in the geographical areas are Arabic speaking.

Contributors: SMP codrafted the paper and protocol documents on which it was based. NS contributed to and was chief investigator (CI) on the peer-reviewed funding proposal and commented on the paper and protocol documents on which it was based specially data collection and intervention in general practice. DN contributed to and was CI on the peer-reviewed funding proposal and contributed to the overall design of the study and intervention and content of the paper and protocol documents on which it was based. LT codrafted the paper and protocol documents on which it was based. ED-W contributed to and was CI on the peer-reviewed funding proposal and contributed to the design of the study and content of the paper and protocol documents on which it was based especially in the education components of the intervention. NZ contributed to and was CI on the peer-reviewed funding proposal and commented on the paper and protocol documents on which it was based especially in relation to the role of general practice. JK contributed to and was CI on the peer-reviewed funding proposal especially the health economic component and commented on the paper and protocol documents on which it was based. JL contributed to and was associate investigator (AI) on the peer-reviewed funding proposal especially the health economic component and commented on the paper and protocol documents on which it was based. MN contributed to and was CI on the peer-reviewed funding proposal especially the nutrition component and commented on the paper. S-TL contributed to and was CI on the peer-reviewed funding proposal especially the informatics component and commented on the paper and protocol documents on which it was based. AL contributed to and was CI on the peer-reviewed funding proposal especially the m-health component and commented on the paper and protocol documents on which it was based. RO contributed to and was AI on the peer-reviewed funding proposal especially the health literacy component and commented on the paper and protocol documents on which it was based. MFH is lead Chief Investigator, developed and led the peer-reviewed funding proposal including the design of the study and intervention and codrafted the paper and protocol documents on which it was based.

Funding: This work is supported by National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) of Australia project grant number APP1125681 (2017). RO is funded in part through an NHMRC Senior Research Fellowship (APP1059122).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The study has been approved by the University of New South Wales Human Research Ethics Committee (HC17474) and ratified by the University of Adelaide Human Research Ethics committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; peer reviewed for ethical and funding approval prior to submission.

References

- 1.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australia’s health 2014. Australia’s health series no. 14. Canberra: AIHW, 2014. Cat. no. AUS 178. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Impact of overweight and obesity as a risk factor for chronic conditions: Australian Burden of Disease Study. Canberra: AIHW, 2017. Contract No: Australian Burden of Disease Study series no.11. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australian health survey: first results, 2011–12. Canberra: Australian Government, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. A picture of overweight and obesity in Australia 2017. Canberra: AIHW, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Australian Bureau of Statistics. Health literacy. Australia: ABS, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Joshi C, Jayasinghe UW, Parker S, et al. . Does health literacy affect patients’ receipt of preventative primary care? A multilevel analysis. BMC Fam Pract 2014;15 10.1186/s12875-014-0171-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kobayashi LC, Wardle J, von Wagner C. Limited health literacy is a barrier to colorectal cancer screening in England: evidence from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Prev Med 2014;61:100–5. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.11.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berkman ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, et al. . Health literacy interventions and outcomes: an updated systematic review. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2011. Contract No: Evidence Report/Technology Assesment No. 199. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dominick GM, Dunsiger SI, Pekmezi DW, et al. . Health literacy predicts change in physical activity self-efficacy among sedentary Latinas. J Immigr Minor Health 2013;15:533–9. 10.1007/s10903-012-9666-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.von Wagner C, Knight K, Steptoe A, et al. . Functional health literacy and health-promoting behaviour in a national sample of British adults. J Epidemiol Community Health 2007;61:1086–90. 10.1136/jech.2006.053967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wolf MS, Gazmararian JA, Baker DW. Health literacy and health risk behaviors among older adults. Am J Prev Med 2007;32:19–24. 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.08.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lim S, Beauchamp A, Dodson S, et al. . Health literacy and fruit and vegetable intake in rural Australia. Public Health Nutr 2017;20:2680–4. 10.1017/S1368980017001483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.von Wagner C, Steptoe A, Wolf MS, et al. . Health literacy and health actions: a review and a framework from health psychology. Health Educ Behav 2009;36:860–77. 10.1177/1090198108322819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schillinger D, Bindman A, Wang F, et al. . Functional health literacy and the quality of physician-patient communication among diabetes patients. Patient Educ Couns 2004;52:315–23. 10.1016/S0738-3991(03)00107-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taggart J, Williams A, Dennis S, et al. . A systematic review of interventions in primary care to improve health literacy for chronic disease behavioral risk factors. BMC Fam Pract 2012;13:49 10.1186/1471-2296-13-49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.ABS. Australian health survey: first results, 2011–12. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics; 2012, 2012. Report No: ABS cat. no. 4364.0.55.001. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Britt H, Miller GC, Henderson J, et al. . General practice activity in Australia 2014–15. Sydney: Sydney University Press, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wadden TA, Volger S, Sarwer DB, et al. . A two-year randomized trial of obesity treatment in primary care practice. N Engl J Med 2011;365:1969–79. 10.1056/NEJMoa1109220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lindström J, Ilanne-Parikka P, Peltonen M, et al. . Sustained reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes by lifestyle intervention: follow-up of the Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study. Lancet 2006;368:1673–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69701-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eriksson MK, Franks PW, Eliasson M. A 3-year randomized trial of lifestyle intervention for cardiovascular risk reduction in the primary care setting: the Swedish Björknäs study. PLoS One 2009;4:e5195 10.1371/journal.pone.0005195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Michie S, Jochelson K, Markham WA, et al. . Low-income groups and behaviour change interventions: a review of intervention content, effectiveness and theoretical frameworks. J Epidemiol Community Health 2009;63:610–22. 10.1136/jech.2008.078725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ahern AL, Aveyard P, Boyland EJ, et al. . Inequalities in the uptake of weight management interventions in a pragmatic trial: an observational study in primary care. Br J Gen Pract 2016;66:e258–e263. 10.3399/bjgp16X684337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Booth HP, Prevost TA, Wright AJ, et al. . Effectiveness of behavioural weight loss interventions delivered in a primary care setting: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fam Pract 2014;31:643–53. 10.1093/fampra/cmu064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.El Haddad N. The interaction between ethnicity and health literacy for weight management among obese Arabic-speaking immigrants in Australian primary health care. Sydney: University of New South Wales, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beauchamp A, Buchbinder R, Dodson S, et al. . Distribution of health literacy strengths and weaknesses across socio-demographic groups: a cross-sectional survey using the Health Literacy Questionnaire (HLQ). BMC Public Health 2015;15:678 10.1186/s12889-015-2056-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ampt AJ, Amoroso C, Harris MF, et al. . Attitudes, norms and controls influencing lifestyle risk factor management in general practice. BMC Fam Pract 2009;10:59 10.1186/1471-2296-10-59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim KK, Yeong LL, Caterson ID, et al. . Analysis of factors influencing general practitioners’ decision to refer obese patients in Australia: A qualitative study Clinical presentation, diagnosis, and management. BMC Family Practice 2015;16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harris MF, Islam FM, Jalaludin B, et al. . Preventive care in general practice among healthy older New South Wales residents. BMC Fam Pract 2013;14:83 10.1186/1471-2296-14-83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Joshi C, Jayasinghe UW, Parker S, et al. . Does health literacy affect patients’ receipt of preventative primary care? A multilevel analysis. BMC Fam Pract 2014;15:171 10.1186/s12875-014-0171-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Faruqi N, Spooner C, Joshi C, et al. . Primary health care-level interventions targeting health literacy and their effect on weight loss: a systematic review. BMC Obes 2015;2:6 10.1186/s40608-015-0035-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chew LD, Bradley KA, Boyko EJ. Brief questions to identify patients with inadequate health literacy. Fam Med 2004;36:588-94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pearson ES. Goal setting as a health behavior change strategy in overweight and obese adults: a systematic literature review examining intervention components. Patient Educ Couns 2012;87:32–42. 10.1016/j.pec.2011.07.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hou SI, Roberson K. A systematic review on US-based community health navigator (CHN) interventions for cancer screening promotion--comparing community- versus clinic-based navigator models. J Cancer Educ 2015;30:173–86. 10.1007/s13187-014-0723-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Faruqi N, Lloyd J, Ahmad R, Harris MF, et al. . Feasibility of an intervention to enhance preventive care for people with low health literacy in primary health care. Aust J Prim Health 2015;21:321–6. 10.1071/PY14061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Passey ME, Laws RA, Jayasinghe UW, et al. . Predictors of primary care referrals to a vascular disease prevention lifestyle program among participants in a cluster randomised trial. BMC Health Serv Res 2012;12:234 10.1186/1472-6963-12-234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dennis SM, Harris M, Lloyd J, et al. . Do people with existing chronic conditions benefit from telephone coaching? A rapid review. Aust Health Rev 2013;37:381–8. 10.1071/AH13005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eakin E, Reeves M, Lawler S, et al. . Telephone counseling for physical activity and diet in primary care patients. Am J Prev Med 2009;36:142–9. 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.09.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.NSW Ministry of Health. Get Healthy: Telephone coaching service Sydney. Sydney: NSW Government, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Partridge SR, McGeechan K, Hebden L, et al. . Effectiveness of a mHealth Lifestyle Program With Telephone Support (TXT2BFiT) to prevent unhealthy weight gain in young adults: randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2015;3:e66 10.2196/mhealth.4530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rathbone AL, Prescott J. The use of mobile apps and sms messaging as physical and mental health interventions: systematic review. J Med Internet Res 2017;19:e295 10.2196/jmir.7740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dosh SA, Holtrop JS, Torres T, et al. . Changing organizational constructs into functional tools: an assessment of the 5 A’s in primary care practices. Ann Fam Med 2005;3 Suppl 2:S50–2. 10.1370/afm.357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jay M, Gillespie C, Schlair S, et al. . Physicians’ use of the 5As in counseling obese patients: is the quality of counseling associated with patients’ motivation and intention to lose weight? BMC Health Serv Res 2010;10:159 10.1186/1472-6963-10-159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Harris MF, Lloyd J, Litt J, et al. . Preventive evidence into practice (PEP) study: implementation of guidelines to prevent primary vascular disease in general practice protocol for a cluster randomised controlled trial. Implement Sci 2013;8:8 10.1186/1748-5908-8-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Harris MF, Parker SM, Litt J, et al. . An Australian general practice based strategy to improve chronic disease prevention, and its impact on patient reported outcomes: evaluation of the preventive evidence into practice cluster randomised controlled trial. BMC Health Serv Res 2017;17:637 10.1186/s12913-017-2586-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Faruqi N, Lloyd J, Ahmad R, et al. . Feasibility of an intervention to enhance preventive care for people with low health literacy in primary health care. Aust J Prim Health 2015;21:321-6 10.1071/PY14061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lau AY, Dunn AG, Mortimer N, et al. . Social and self-reflective use of a web-based personally controlled health management system. J Med Internet Res 2013;15:e211 10.2196/jmir.2682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lau AY, Sintchenko V, Crimmins J, et al. . Impact of a web-based personally controlled health management system on influenza vaccination and health services utilization rates: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2012;19:719–27. 10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mortimer NJ, Rhee J, Guy R, et al. . A web-based personally controlled health management system increases sexually transmitted infection screening rates in young people: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2015;22:805–14. 10.1093/jamia/ocu052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lau AY, Dunn A, Mortimer N, et al. . Consumers’ online social network topologies and health behaviours. Stud Health Technol Inform 2013;192:77–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Webb TL, Joseph J, Yardley L, et al. . Using the internet to promote health behavior change: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of theoretical basis, use of behavior change techniques, and mode of delivery on efficacy. J Med Internet Res 2010;12:e4 10.2196/jmir.1376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.DiFilippo KN, Huang WH, Andrade JE, et al. . The use of mobile apps to improve nutrition outcomes: A systematic literature review. J Telemed Telecare 2015;21:243–53. 10.1177/1357633X15572203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Payne HE, Lister C, West JH, et al. . Behavioral functionality of mobile apps in health interventions: a systematic review of the literature. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2015;3:e20 10.2196/mhealth.3335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhao J, Freeman B, Li M. Can mobile phone apps influence people’s health behavior change? An evidence review. J Med Internet Res 2016;18:e287 10.2196/jmir.5692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Manganello J, Gerstner G, Pergolino K, et al. . The relationship of health literacy with use of digital technology for health information: implications for public health practice. J Public Health Manag Pract 2017;23:380–7. 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McKenzie SH, Harris MF. Understanding the relationship between stress, distress and healthy lifestyle behaviour: a qualitative study of patients and general practitioners. BMC Fam Pract 2013;14:166 10.1186/1471-2296-14-166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Osborne RH, Batterham RW, Elsworth GR, et al. . The grounded psychometric development and initial validation of the Health Literacy Questionnaire (HLQ). BMC Public Health 2013;13:658 10.1186/1471-2458-13-658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Norman CD, Skinner HA. eHEALS: The eHealth Literacy Scale. J Med Internet Res 2006;8:e27 10.2196/jmir.8.4.e27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Smith BJ, Bauman AE, Bull FC, et al. . Promoting physical activity in general practice: a controlled trial of written advice and information materials. Br J Sports Med 2000;34:262–7. 10.1136/bjsm.34.4.262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hendrie GA, Baird D, Golley RK, et al. . The CSIRO Healthy diet score: an online survey to estimate compliance with the australian dietary guidelines. Nutrients 2017;9:47 10.3390/nu9010047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.NSW Ministry of Health. NSW Population Health Survey. Sydney: NSW Government, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A, et al. . Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual Life Res 2011;20:1727–36. 10.1007/s11136-011-9903-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yeazel MW, Lindstrom Bremer KM, Center BA. A validated tool for gaining insight into clinicians’ preventive medicine behaviors and beliefs: the preventive medicine attitudes and activities questionnaire (PMAAQ). Prev Med 2006;43:86–91. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.03.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liaw ST, Kearns R, Taggart J, et al. . The informatics capability maturity of integrated primary care centres in Australia. Int J Med Inform 2017;105:89–97. 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2017.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-023239supp001.pdf (66.2KB, pdf)