Abstract

Objective

To identify factors predictive of pregnancy-related anxiety (PRA) among women in Mwanza, Tanzania.

Design

A cross-sectional study was used to explore the relationship between psychosocial health and preterm birth.

Setting

Antenatal clinics in the Ilemela and Nyamagana districts of Mwanza, Tanzania.

Participants

Pregnant women less than or equal to 32 weeks’ gestational age (n=212) attending the two antenatal clinics.

Measures

PRA was measured using a revised version of the 10-item PRA Questionnaire (PRA-Q). Predictive factors included social support (Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support), stress (Perceived Stress Scale), depression (Edinburg Postpartum Depression Scale) and sociodemographic data. Bivariate analysis permitted variable selection while multiple linear regression analysis enabled identification of predictive factors of PRA.

Results

Twenty-five per cent of women in our sample scored 13 or higher (out of a possible 30) on the PRA-Q. Perceived stress, active depression and number of people living in the home were the only statistically significant predictors of PRA in our sample.

Conclusions

Our findings were contrary to most current literature which notes socioeconomic status and social support as significant factors in PRA. A greater understanding of the experience of PRA and its predictive factors is needed within the social cultural context of low/middle-income countries to support the development of PRA prevention strategies specific to low/middle income countries.

Keywords: pregnancy-related anxiety, anxiety, women’s health, pregnancy, global health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study to examine the predictive factors for pregnancy-related anxiety (PRA) among pregnant women in Tanzania and identifies the importance of cultural context when examining PRA among pregnant women in low/middle-income countries.

This study used secondary data limiting variable options to those already included in the primary longitudinal study.

There is no established normative reference to indicate when a woman is at ‘high risk’ for PRA. Thus factors identified in this study should only be considered in relation to relative (ie, higher or lower) PRA scores.

Convenience sampling was employed and consequently results cannot be generalised to all pregnant women in the Ilemela and Nyamagana districts of Tanzania.

The sample size of the current study may have limited the power of some of the statistical analysis making it difficult to make inferences.

Introduction

Pregnancy-related anxiety (PRA) is characterised by anxiety pertaining to the pregnancy, including labour and delivery, the fetus or infant’s health, the mother’s health, accessibility and quality of healthcare resources, and/or the ability to parent.1–4 PRA is a distinct and different phenomenon than general anxiety occurring concurrent to pregnancy1 and has stronger correlations to preterm birth (PTB) (birth at less than 37 weeks’ gestation) than more commonly studied general anxiety or depression.2 4–6 An estimated 85% of PTB globally occurs in Africa and Asia.7 Africa has the highest rate of PTB where some regions reach 17.5%7; approximately 14.3% of births are preterm in Eastern Africa.

PRA prevalence estimates in high-income countries range from 6% to 29%8–11; however, high-risk populations tend to yield higher rates of PRA.9 Among a sample of pregnant women from Tanzania (a low-income country12), in the city of Mwanza, the rate of PRA was 18.3%, which was associated with antenatal depression (OR 1.36, 95% CI 1.23 to 1.5) (Rwakarema, unpublished data, 2013).13 In the lower middle-income country of India,12 in the city of Kerala, prevalence of severe PRA ranged from 0.4% to 22% depending on the trimester, but at least 74% of Indian women experienced ‘moderate levels’ of PRA in all trimesters which was not operationally defined.14 Prevalence of PRA varies in part due to methodological heterogeneity (eg, characteristics of sample, timing of measurement) and clinical heterogeneity (eg, measuring anxiety during pregnancy rather than PRA14).

Within high-income countries, non-Caucasian ethnicity, low family income and limited social supports are consistently noted as prominent risk factors for PRA.2 15 16 In low/middle-income countries (LMIC), it is unknown if these remain the most prominent risk factors for PRA. In Tanzania, 67% of the population falls below the poverty line and 99% of Tanzanians are of African ethnicity.17 Moreover, 69% of the population lives in rural areas and there are only three physicians per 100 000 people17 which may result in concerns related to healthcare resources which further contributes to the potential for PRA. As such, it seems reasonable to anticipate PRA prevalence in LMIC such as Tanzania may be comparable to PRA rates in high-risk populations within high-income countries.

Unfortunately, there is a dearth of literature examining PRA in LMIC; only 8% of LMIC are represented in literature regarding all common mental illness during the prenatal period.18 This lack of contextually relevant literature makes it difficult to develop practice guidelines or protocols to address PRA in these countries. Moreover, in many LMIC like Tanzania, many women come from similar socioeconomic backgrounds and it remains unclear why some women develop severe PRA and others do not. Alternative theories of stress can offer insight about stressful events, such as PRA, in unexamined populations. Lazarus and Folkman19 suggest that stress occurs when people are faced with a situation they deem a possible threat and cannot access the resources required to manage the threat. In accordance with this theory, the differences in sociocultural context between high-income countries and LMIC may be that LMIC hold different risk factors for PRA than high-income countries. Differences in countries’ public health education may alter the amount of anxiety women have about the physical symptoms of pregnancy as they are more or less aware of what to expect and what is normal.20 Moreover, difference in accessibility to healthcare services can affect women’s appraisal of whether or not adequate prenatal care is attainable. This doubt can increase concerns about pregnancy complications, delivery or infant care, particularly if access to healthcare is limited or women have had previous negative healthcare experiences.2 Consequently, factors associated with PRA in high-income countries should not be assumed true for LMIC.

We used the Social Ecology Model for Health Promotion21 to identify predictive factors. The model proposes health promotion is most effective when we consider the interaction of peoples’ attributes and both their physical environment and social climate.21 As people change their environment it will contribute to their change in health. In this model, the notion of ‘environment’ is multidimensional and can include tangible attributes (ie, upsetting events in the community) or social constructs, objective qualities or perceived qualities, and/or social climate or physical surroundings.21 Additionally, the Social Ecology Model for Health Promotion asserts that human–environment interactions should be considered on both small and large scales (eg, individuals, families, communities and populations).21 Therefore, in order to thoroughly examine factors associated with PRA in women in the low-income country of Tanzania, we examine attributes of pregnant women, their families, their communities and their environment. We sought to answer the research question: what predictive factors are associated with PRA for women attending antenatal clinics in the Ilemela and Nyamagana districts of Tanzania, Africa?

Methods

Study design

We used data collected during women’s first attendance at prenatal clinic (gestational age 6–32 weeks). These women were enrolled in a prospective longitudinal study that explored the relationship between psychosocial health and PTB among women in Mwanza, Tanzania (Premji unpublished data, 2013). A collaborative research team comprised of faculty and graduate students from University of Calgary and Catholic University of Health and Allied Sciences (CUHAS) in Mwanza, Tanzania, and local registered nurses, who also served as fieldworkers, collected data at four time points throughout participants’ pregnancies (first trimester, early second trimester, late second trimester and early third trimester). During the first time point, women were coached to return to the clinic every 6 weeks until 32 weeks’ gestation, then were seen at delivery and again 6 weeks post partum (Premji unpublished data, 2013). At each point of contact, participants received a perinatal mental health assessment; private space was provided to complete questionnaires (Premji unpublished data, 2013). The Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board at the University of Calgary (approval numbers REB 13-0399 and 16-1579) and the CUHAS/Bugando Medical Centre Research Ethical Committee (CREC/062/2013) approved these studies (ie, primary and secondary analyses). The larger study was also approved by the Tanzania National Institute of Medical Research-Lake Zone Institutional Review Board (MR/53/100/254 and MR/53/100/160).

Patient involvement

Patients and/or public were not involved in the design of the study.

Setting and participants

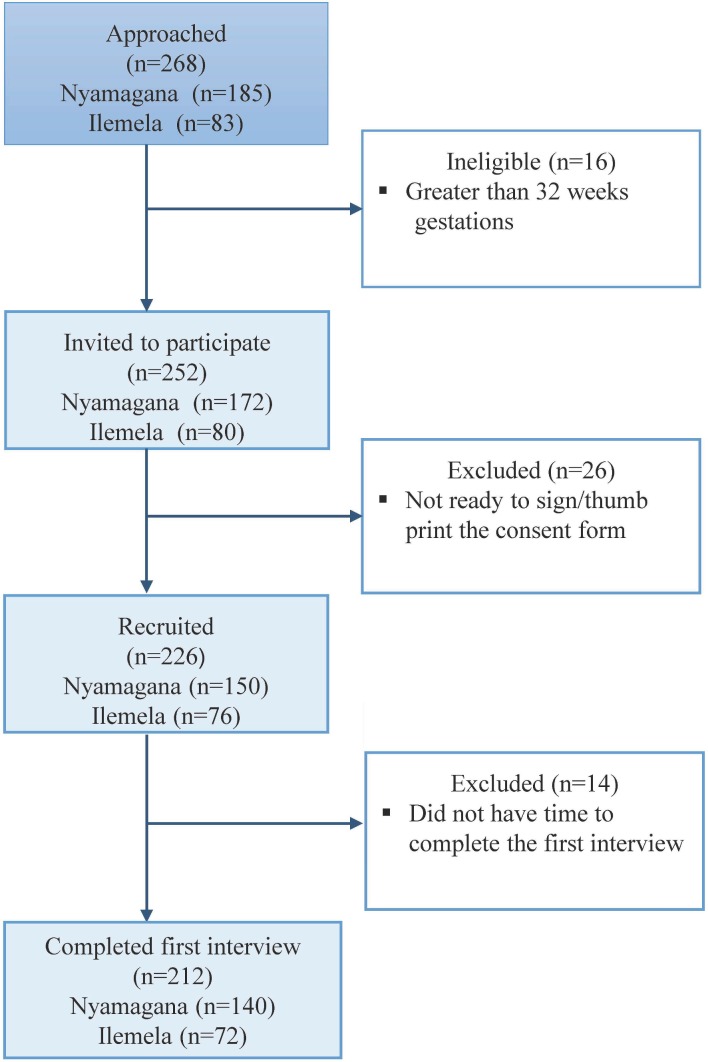

A convenience sample of 212 women was recruited using a systematic sampling approach from antenatal clinics in the Ilemela (n=72) and Nyamagana (n=140) districts of Tanzania from June 2013 to January 2015 (Premji unpublished data, 2013). The sample was comprised of women who spoke Swahili or English and were 32 weeks’ gestational age or less at the time of enrolment based on women’s last menstrual period. Adolescent mothers were included as they were classified as emancipated minors (Premji unpublished data, 2013). Women who self-reported comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes, malaria or HIV were not excluded due to the prevalence of these illnesses. Recent work within this sample revealed that the high prevalence of HIV coupled with minimal health knowledge has resulted in women with and without HIV sharing similar concerns about the illness and potential effects on their baby.20 The nurse in-charge was the first to approach and invite participation from eligible women in the waiting room of the antenatal clinics. A member of the research team then obtained informed consent from women who agreed to participate (see figure 1) (Premji 2013, unpublished).

Figure 1.

Recruitment flow diagram.

Data collection

A general questionnaire was used to collect sociodemographic data including age, education, income and comorbidities (Premji unpublished data, 2013). PRA was measured using a revised version of the 10-item PRA Questionnaire (PRA-Q) that assesses feelings about health during pregnancy, infant or baby’s health, and labour and delivery.22 23 Each item was a 4-point Likert scale of 0–3; a cumulative score was given out of a possible 30 points.22 Information on household incomes was difficult to obtain due to cultural norms and traditions.13 Consequently, socioeconomic welfare was assessed using a Likert scale questionnaire focused on the acquisition of assets (eg, car, motorcycle, bicycle), living standards (eg, access to water and number of meals eaten per day) and other wealth status (eg, employment).13 24 Most questions were dichotomous (yes or no) with an associated score of 1 or 2 with the exception of three questions; roof type and meals per day provided three possible answers with associated scores of 1–3 and water source had five possible answers with scores from 1–5. The final score on the Socio-Economic Welfare Questionnaire (SEW-Q) was a sum of all the answers for a maximum possible score of 29. Social support was rated using the 12-item Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support.25 This scale includes questions about the relationship of supportive people to the participant, the perceived level of support the participant receives from her support network and the extent to which the participant feels cared for by the people closest to her.25 This scale has high internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s α >0.90). Perceived stress (PS) was measured with a 10-item tool (4-point Likert scale) examining the frequency of increased stress, perceived level of control over their life and stressful events, and ability to cope with stress. A cumulate score was given out of a possible 40 with higher scores indicating increased stress.26 Evaluation of the PS scale has consistently shown adequate reliability (Cronbach’s α >0.70) and has been used with a variety of populations and translated into 25 languages.27 However, empirical evaluation has not been completed on these translated versions or with populations other than college students or the employed.27 The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), a self-reported 10-item scale, was used to screen for depression and identify at-risk mothers. Empirical evaluation demonstrates good reliability (Cronbach’s α=0.83).28 This scale has been extensively tested in both pregnant and postnatal populations and is widely accepted for global populations with translations in several languages.29 30 The EPDS has been used and tested in various African countries and translated into many languages including Swahili.13 31

Statistical analysis

For bivariate analysis, variables of interests (table 1) were selected based on factors identified in the current literature, the theory of cognitive appraisal19 and the social ecological model for health promotion.21 Bivariate analyses identified which continuous variables had a relationship with the PRA total score. Nominal variables with more than two values (ie, marital status, occupation) were converted into dichotomous variables (ie, in relationship or not) and analysed with Mann-Whitney U tests as PRA was not normally distributed. Converted variables found to have a significant association with PRA total score were then expanded and each variable’s original values (ie, coupled, married, common law, divorced, and so on) were analysed as separate dichotomous variables using Mann-Whitney U test for an association with PRA total score. Ordinal variables (ie, education) were analysed with Kruskal-Wallis tests as PRA was not normally distributed. Variables with a significance level of p≤0.25 in the bivariate analyses were included in the multiple linear regression analyses.32 Variables known to have clinical relevance such as socioeconomic welfare score and marital status were also included regardless of their statistical significance.

Table 1.

Variable selected for bivariate analysis

| Individual | Family | Community |

| EPDS score* | Sum of SEW-Q score* | Events in the community upsetting to you |

| Age of participant | Gravidity | Perceived social support score |

| Mother born in Mwanza | Current marital status† | Healthcare facility |

| Mother’s highest level education | Mother’s main occupation | |

| PS score* | Father’s main occupation | |

| History of hypertension | Father’s highest level of education* | |

| History of depression* | Total number of pregnancies | |

| History of gestational diabetes | Total number of live births | |

| History of schistosomiasis | Previously had preterm* | |

| History of syphilis | Previously had a male baby | |

| History of HIV* | Number of people living in the home* | |

| History of malaria | Planned pregnancy* | |

| History of anaemia | Gestational age at first visit |

*Predictor variable in regression analysis.

†Married and separated were dichotomised predictor variables in regression analysis.

EPDS, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; PS, perceived stress; SEW-Q, Socio-Economic Welfare Questionnaire.

Multiple linear regression modelling was employed with PRA total score as the dependent variable. In order to assess variables associated with the most severe cases of PRA, PRA scores were divided into quartiles and only cases with PRA scores in the top and bottom quartiles were analysed in this multiple regression analysis. Given the rigorous variable selection process, a backwards input method was used. Variables were then removed starting with the variables that were least statistically significant. A two-sided p value of ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant for all multiple linear regression analyses. Residual of error values were then examined in a scatter plot, Q-Q plot and histogram to verify the assumptions of normal distribution and homoscedasticity were satisfied.

We conducted supplemental analyses to provide a comparison with the primary analyses which only used cases with PRA scores in the first and fourth quartiles. The first supplemental analysis employed the same multiple linear regression process as the primary analysis but included all PRA scores. We employed the same variable selection method described in the primary analysis. Currently, there is no empirically tested, or commonly accepted, method for operationalising PRA-Q scores into levels of severity. Thus, our primary analysis maintained rigour by leaving these scores as a continuous variable. To evaluate how our results may compare with studies that have categorised PRA scores, we completed a second supplemental analysis. Using all 212 cases, PRA scores were dichotomised in accordance with the work of Fairlie et al33; high anxiety was defined as three or more answers of ‘3’ (very much) on the PRA-Q. All other scores were categorised as low-moderate anxiety. Bivariate and χ2 tests were conducted where appropriate to identify factors associated with high, or low-moderate PRA.

Results

The sample comprised 72 women from the Ilemela district and 140 women from the health centre in Nyamagana (n=212) with a median age of 26 years (range 16–44 years). Approximately three-quarters of participants (78.2%) were multiparous, the majority of participants were in a relationship (89.6%) and over three-quarters of participants (77.8%) identified that they were married. Although nearly all participants (97.2%) had some level of formal education, most had only completed primary school (64.6%). Socioeconomic status was higher than expected with 57.1% of participants scoring 12 or better (out of 18) on the SEW-Q and 9.0% scoring 5 or less. PRA-Q scores ranged from 0 to 24 with a median score of 10 (IQR=8–13). When PRA was dichotomised as ‘high’ and ‘low-moderate’ categories, 6.1% of participants (n=13) had high anxiety. Table 2 shows the demographic characteristics and PRA scores of the study’s sample.

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics

| Total N=212 |

Nyamagana n=140 (66%) |

Ilemela n=72 (34%) |

|

| Median (range) | Median (range) | Median (range) | |

| Age (years) | 26 (16–44) | 33 (16–44) | 29 (17–40) |

| GA (weeks) at first visit | 24 (6–32) | 23 (6–32) | 26 (8–32) |

| N (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Primiparous | 50 (21.8) | 33 (21.6) | 17 (22.7) |

| Born in Mwanza | 71 (33.5) | 52 (37.1) | 19 (26.4) |

| Primary education | 137 (64.2) | 104 (74.3) | 33 (45.8) |

| > Primary education | 69 (32.5) | 33 (23.6) | 36 (50.0) |

| Married | 165 (77.8) | 105 (75.0) | 60 (85.7) |

| Employed | 138 (60.3) | 92 (60.1) | 46 (61.3) |

| Median (range) | Median (range) | Median (range) | |

| Sum of SEW-Q scores | 12 (2–18) | 12 (2–18) | 13 (2–16) |

| Perceived social support score | 59 (20–84) | 59 (21–84) | 59 (20–80) |

| Perceived stress score | 19 (1–36) | 18 (1–36) | 21 (8–33) |

| EPDS | 8 (0–26) | 7 (0–25) | 9 (0–26) |

| PRA-Q total score | 10 (0–24) | 10 (0–24) | 12 (2–24) |

EPDS, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; GA, gestational age; PRA-Q, Pregnancy-Related Anxiety Questionnaire; PS, perceived stress; SEW-Q, Socio-Economic Welfare Questionnaire.

In the primary analysis, PRA scores were quartiled and only cases from the first and fourth quartiles were used (n=90). The first quartile scores ranged from 0 to 7 and the fourth quartile scores ranged from 13 to 24. The variables included in the multiple linear regression analyses are shown in table 1. The results of the primary regression (table 3) indicated that PS score, EPDS score and number of people living in the home were significant predictors of PRA (R2=0.339, F(3,74)=12.657, p=0.000) (adjusted R2=0.312). PS score and EPDS score were positively associated with PRA score, whereas the number of people living in the home was negatively associated with PRA score. There was no indication of multicollinearity as each of these predictors met the criteria for statistical significance (p≤0.05), had a variance inflation factor of less than 2 and a tolerance greater than 0.05. While the EPDS is supposed to measure postpartum depression, there is concern the scale contains an anxiety subscale.34 To account for a potential spurious relationship between this anxiety subscale and PRA, the EPDS scores were recalculated, excluding the scores for two anxiety-related questions. Bivariate analysis indicated the recalculated EPDS scores and full EPDS scores shared the same correlation with PRA score (rs=0.511, p=0.000). When the linear regression modelling was rerun using the recalculated EPDS scores the model summary was only marginally changed (R2=0.338, F(3,74)=2.607, p=0.000) (adjusted R2=0.311). The total of the two anxiety questions from the EPDS was analysed as a separate variable. This variable showed a positive correlation with PRA scores (rs=0.422, p=0.000) but was not a statistically significant predictor in the regression models.

Table 3.

Regression model of factors associated with PRA score

| B | SE B | β | t | p values | |

| PS score | 0.306 | 0.121 | 0.328 | 2.527 | 0.014 |

| EPDS score | 0.328 | 0.136 | 0.316 | 2.416 | 0.018 |

| Number of people living in home | −0.718 | 0.342 | −0.204 | −2.102 | 0.039 |

EPDS, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; PRA, pregnancy-related anxiety; PS, perceived stress.

In the first supplemental analysis (using all cases, n=212), PRA had a significant association (p≤0.05) with EPDS score, recalculated EPDS score, PS, SEW-Q score, a history of HIV and healthcare facility. The results of this regression analysis were similar to the regression modelling using the first and fourth quartile PRA scores; results indicated PS score and EPDS score were statistically significant predictors of PRA (R2=0.196, F(2,209)=25.394, p=0.000) (adjusted R2=0.188). Both PS score and EPDS score maintained a positive correlation with PRA. This regression was rerun using the recalculated EPDS scores and the model summary was again only marginally different (R2=0.195, F(2,209)=25.243, p=0.000) (adjusted R2=0.187) with the same final predictors.

In the second supplemental bivariate analysis with dichotomised PRA, the number of people living in the home, PS score and EPDS scores showed significant associations (p≤0.05) with high or low-moderate PRA. Fisher’s exact test showed PRA to have a significant association with if the mom was born in Mwanza, and if the pregnancy was planned. Eighty-five per cent (n=11) of the participants with high anxiety had not planned their pregnancy. χ2 analysis showed presence of depression (an EPDS score of 13 or higher29) was twofold in women with high PRA scores (53.8%) compared with women with low PRA scores (27.1%) (p=0.04). When EPDS scores were recalculated without the anxiety questions, the presence of depression remained about twofold in women with high PRA scores compared with women with low PRA scores (23.1% and 11.6%, respectively). However, these results were not statistically significant (p=0.203).

Discussion

Twenty-five per cent of women in our sample scored 13 or higher (out of a possible 30) on the PRA-Q, and 6.1% of participants met the threshold for ‘high anxiety’.33 Regardless of how PRA was operationalised (continuous, dichotomised or limited to only the highest and lowest scores), EPDS score and PS score consistently had a positive correlation with PRA and were significant predictors in the regression models. Current literature substantiates the identified association between depression and PRA.1 13 Pregnant women more commonly experience comorbid anxiety and depression rather than one of these afflictions alone.13 35 However, there appears to be limited understanding of why this comorbidity exists and which develops first, depression or anxiety. Consideration of the theory of stress, appraisal and coping19 combined with the nuances of this sample’s cultural context provides insight in this inquiry. Lazarus and Folkman19 posit that stress results when an event is appraised as a possible threat to one’s well-being and the resources to mitigate the event are deemed unattainable. Moreover, factors such as novelty and time proximity to the event can affect the perception of the threat’s severity.19 In accordance with this theory, the lack of basic health knowledge, coupled with restricted access to healthcare facilities, and the low socioeconomic standing of most Tanzanians create an environment where pregnancy could commonly result in stress or anxiety.17 20 Moreover, social customs in Tanzania deter the discussion of personal matters with anyone: friends, family or spouses.20 A phenomenological study used a subsample of our participants to explore moderate to severe PRA. This study identified common feelings of isolation and alienation among participants as their anxiety worsened and there was no perceived acceptable forum to discuss their fears; ultimately, women endorsed the isolation evolving into sadness.20 36 Even in cases where women surrounded themselves with family, there was still a reluctance to discuss their concerns. Our primary analysis revealed a negative correlation between number of people living in the home and PRA. More people in the home increases the likelihood that the mother has someone she may feel comfortable talking to. It is therefore conceivable that in this populace, severe PRA may trigger an internal conflict of wanting to express these fears while worrying that this is not acceptable, which results in feelings of isolation and subsequent depression.

Interestingly, the factors most commonly associated with PRA in current literature did not hold significance in this study. Socioeconomic welfare score showed a significant correlation with PRA only when all participants were used and PRA was a continuous variable. When PRA scores were dichotomised or only participants with the PRA scores in the first and fourth quartiles were used, the correlation with socioeconomic welfare score lost statistical significance, and did not show significant predictive properties. Perceived social support score, marital status and mother’s occupation also failed to have a significant association. Active depression is the only factor found to predict PRA in our study, which is also consistently correlated to PRA in current literature.1 13 Our findings are remarkably contrary to the current literature, which consistently lists social supports, ethnicity and economic status as key risk factors.2 15 16 Our findings serve as a caution to generalise findings on PRA from high-income countries to populations in LMIC. These gross variations from current research may reflect the limited research available from LMIC.18

We identified only two studies (each with two articles), one from India and the other from Tanzania, which used the pregnancy-specific anxiety inventory14 37 and PRA-Q (Rwakarema unpublished data, 2013)13 to measure PRA, respectively. In the Indian study, younger age and not living with extended family were associated with higher PRA.14 37 Comparatively, results of the current study found no statistically significant relationship with the mothers’ age in any of the analyses (primary or secondary). Number of people living in the home was not statistically significant in either analysis where PRA was maintained as a continuous variable (primary or first supplemental). When PRA was dichotomised, however, number of people living in the home showed statistically significant negative correlation with PRA. The nature of relationship between the mother and people living in the home was not examined in the current study, thus comparison between our study and the Indian study is difficult. In the Tanzanian study, PRA was noted to have a statistically significant relationship with prenatal depression (Rwakarema unpublished data, 2013).13 The Tanzanian study was examining factors associated with antenatal depression, consequently the underlying aim of the study was different (ie, clinical heterogeneity).

Despite the vast differences in culture and socioeconomic standing it makes sense that globally, women can experience the same condition, PRA, for different reasons. Pregnancy and childbirth have high risk of death for the mother and baby in Tanzania.38 The neonatal mortality rate is about 26 for every 1000 lives births and the maternal mortality rate is 398–454 for every 100 000 lives births.38 In the previously mentioned phenomenological study, fears about health during pregnancy were a commonly noted factor contributing to PRA.20 36 High likelihood of death may be an unfortunate reality for populations in LMIC resulting in a fear of death having a greater effect on overall PRA than in women from high-income counties. With the multidimensional nature of PRA, women may assign greater emphasis on different domains of PRA based on issues most relevant for their cultural context.39

The notion of novelty can critically change the perceived threat in an event.19 Pregnancy may be uniquely novel in its accompaniment of physiological and psychological emotional investment coupled with the distinct outcome of creating human life. One possible explanation is that pregnancy may hold an unparalleled element of novelty (thus propensity to induce anxiety) regardless of a woman’s background or gravidity. Differences in social norms and fundamental values, however, may change what someone considers threatening or stressful.19 In the context of this study, sociocultural norms such as dynamics between men and women may change the effect of social supports on PRA scores. The subsample of women enrolled in the phenomenological study of PRA often described their husbands growing distant during the pregnancy, which had an exacerbating effect on their anxiety rather than calming.20 Many of the fears voiced by women in Tanzania were due to limited basic health and pregnancy knowledge; many times normal sensations resulted in fear of death for the mother or baby.20 These differences in findings outline the need for more research exploring the notion of PRA in LMIC and between LMIC and high-income countries.

Limitations

Convenience sampling was employed and consequently results cannot be generalised to all pregnant women in the Ilemela and Nyamagana districts of Tanzania. Moreover, the lack of comparable studies in LMIC makes it difficult to identify potential anomalies in these findings. There are no standardised screening tools for PRA or commonly accepted categorisation methods for the tools available,39 making it difficult to compare findings between studies or compare characteristics between levels of severity of PRA. Moreover, within current literature there is no empirically tested way to operationalise PRA scores. The PRA-Q examines broad concepts of PRA making it an effective screening tool but difficult to identify severity of PRA or clinical diagnoses.39 40 This was a secondary data analysis limiting variable options to those already included in the longitudinal study. Findings in the regression modelling only explain 20%–34% of the change in PRA scores across our sample. Consequently, there are still significant factors not identified in this study.

Conclusion

Active depression is one of the only factors consistently correlated to PRA in both our study and current literature. Given the sociocultural differences between populations in high-income countries and LMIC, the unique psychological complexities of pregnancy and the personal nature of how people assess events as stressful, findings should not be generalised across these populations. Ultimately, more research is needed on PRA universally and the reason for comorbidity between depression and PRA. In LMIC, before predictive factors and prevention strategies can be identified, further fundamental exploration of PRA is needed to better understand how this phenomenon fits within these sociocultural settings.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the research team in Mwanza, Tanzania, who completed the larger quantitative study, including affiliates with the Catholic University of Health and Allied Sciences. The primary author acknowledges the research team’s hard work and allowing the use of the data to complete this analysis. The authors also thank and acknowledge the women of Tanzania who took time to participate in the study and allowed them to learn from their lives and experiences.

Footnotes

VW and SSP contributed equally.

Contributors: VW and SSP worked together to develop the research question, study design and analytic plan. SSP, NL and GM provided consultation from the research design through to the manuscript development, and directed the analysis of the study. ECN, local lead in Mwanza, translated documents, obtained ethics approval and supervised research assistants. All authors have contributed to the work and approved the manuscript.

Funding: The University of Calgary Research Grant (URGC) Program, SEED Grant, funded the larger quantitative study. VW’s graduate studies were support by scholarships including Entrance Scholarship for Master of Nursing Program, Faculty of Nursing Graduate Entrance Scholarship, Queen Elizabeth II Scholarship, and Graduate Knowledge Translation Assistantship from Faculty of Nursing.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: University of Calgary Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board (REB13-0399: larger study; REB14-0660: this study; and REB14-0660-MOD-1: to include postpartum women) and the Catholic University of Health and Allied Sciences.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The data set generated during our study is not publicly available as consent for secondary use was not obtained from study participants. Please contact the corresponding author for additional information.

References

- 1. Huizink AC, Mulder EJ, Robles de Medina PG, et al. Is pregnancy anxiety a distinctive syndrome? Early Hum Dev 2004;79:81–91. 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2004.04.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dunkel Schetter C. Psychological science on pregnancy: stress processes, biopsychosocial models, and emerging research issues. Annu Rev Psychol 2011;62:531–58. 10.1146/annurev.psych.031809.130727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dunkel Schetter C, Tanner L. Anxiety, depression and stress in pregnancy: implications for mothers, children, research, and practice. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2012;25:141–8. 10.1097/YCO.0b013e3283503680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Guardino CM, Dunkel Schetter C. Understanding pregnancy anxiety. Zero to Three 2014;35:12–22. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Glynn LM, Schetter CD, Hobel CJ, et al. Pattern of perceived stress and anxiety in pregnancy predicts preterm birth. Health Psychol 2008;27:43–51. 10.1037/0278-6133.27.1.43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rose MS, Pana G, Premji S. Prenatal maternal anxiety as a risk factor for preterm birth and the effects of heterogeneity on this relationship: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Biomed Res Int 2016;2016:1–18. 10.1155/2016/8312158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Beck S, Wojdyla D, Say L, et al. The worldwide incidence of preterm birth: a systematic review of maternal mortality and morbidity. Bull World Health Organ 2010;88:31–8. 10.2471/BLT.08.062554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Arch JJ. Pregnancy-specific anxiety: which women are highest and what are the alcohol-related risks? Compr Psychiatry 2013;54:217–28. 10.1016/j.comppsych.2012.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fleuriet KJ, Sunil TS. Perceived social stress, pregnancy-related anxiety, depression and subjective social status among pregnant Mexican and Mexican American women in south Texas. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2014;25:546–61. 10.1353/hpu.2014.0092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jolly J, Walker J, Bhabra K. Subsequent obstetric performance related to primary mode of delivery. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1999;106:227–32. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1999.tb08235.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rubertsson C, Hellström J, Cross M, et al. Anxiety in early pregnancy: prevalence and contributing factors. Arch Womens Ment Health 2014;17:221–8. 10.1007/s00737-013-0409-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.The World Bank. World bank country and lending groups. https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups (accessed 5 Oct 2017).

- 13. Rwakarema M, Premji SS, Nyanza EC, et al. Antenatal depression is associated with pregnancy-related anxiety, partner relations, and wealth in women in Northern Tanzania: a cross-sectional study. BMC Womens Health 2015;15:68 10.1186/s12905-015-0225-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Madhavanprabhakaran GK, D’Souza MS, Nairy KS. Prevalence of pregnancy anxiety and associated factors. International Journal of Africa Nursing Sciences 2015;3:1–7. 10.1016/j.ijans.2015.06.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gurung RAR, Dunkel-Schetter C, Collins N, et al. Psychosocial predictors of prenatal anxiety. J Soc Clin Psychol 2005;24:497–519. 10.1521/jscp.2005.24.4.497 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lee AM, Lam SK, Sze Mun Lau SM, et al. Prevalence, course, and risk factors for antenatal anxiety and depression. Obstet Gynecol 2007;110:1102–12. 10.1097/01.AOG.0000287065.59491.70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. United States of America Central Intelligence Agency. The world Factbook: Africa Tanzania. 2016. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/tz.html (accessed 5 Oct 2017).

- 18. Fisher J, Cabral de Mello M, Patel V, et al. Prevalence and determinants of common perinatal mental disorders in women in low- and lower-middle-income countries: a systematic review. Bull World Health Organ 2012;90:139–49. 10.2471/BLT.11.091850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal, and coping. NewYork, NY: Springer, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rosario MK, Premji SS, Nyanza EC, et al. A qualitative study of pregnancy-related anxiety among women in Tanzania. BMJ Open 2017;7:e016072 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Stokols D. Establishing and maintaining healthy environments. Toward a social ecology of health promotion. Am Psychol 1992;47:6–22. 10.1037/0003-066X.47.1.6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rini CK, Dunkel-Schetter C, Wadhwa PD, et al. Psychological adaptation and birth outcomes: the role of personal resources, stress, and sociocultural context in pregnancy. Health Psychol 1999;18:333–45. 10.1037/0278-6133.18.4.333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wadhwa PD, Sandman CA, Porto M, et al. The association between prenatal stress and infant birth weight and gestational age at birth: a prospective investigation. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1993;169:858–65. 10.1016/0002-9378(93)90016-C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rutstein S, Johnson K. The DHS wealth index. DHS comparative reports No 6. Calverton, MD: ORC Macro, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hardan-Khalil K, Mayo AM. Psychometric properties of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Clin Nurse Spec 2015;29:258–61. 10.1097/NUR.0000000000000148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav 1983;24:385–96. 10.2307/2136404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lee E-H. Review of the psychometric evidence of the perceived stress scale. Asian Nurs Res 2012;6:121–7. 10.1016/j.anr.2012.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bunevicius A, Kusminskas L, Bunevicius R. P02-206 Validity of the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale. European Psychiatry 2009;24:S896 10.1016/S0924-9338(09)71129-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry 1987;150:782–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Navarro P, Ascaso C, Garcia-Esteve L, et al. Postnatal psychiatric morbidity: a validation study of the GHQ-12 and the EPDS as screening tools. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2007;29:1–7. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2006.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tsai AC, Scott JA, Hung KJ, et al. Reliability and validity of instruments for assessing perinatal depression in African settings: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2013;8:e82521 10.1371/journal.pone.0082521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S, Sturdivant RX, et al. Applied logistic regression. 3rd edn Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Fairlie TG, Gillman MW, Rich-Edwards J. High pregnancy-related anxiety and prenatal depressive symptoms as predictors of intention to breastfeed and breastfeeding initiation. J Womens Health 2009;18:945–53. 10.1089/jwh.2008.0998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Brouwers EP, van Baar AL, Pop VJ. Does the edinburgh postnatal depression scale measure anxiety? J Psychosom Res 2001;51:659–63. 10.1016/S0022-3999(01)00245-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Field T, Diego M, Hernandez-Reif M, et al. Comorbid depression and anxiety effects on pregnancy and neonatal outcome. Infant Behav Dev 2010;33:23–9. 10.1016/j.infbeh.2009.10.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rosario K. Pregnancy-related anxiety in Mwanza, Tanzania: a qualitative approach [Masters thesis]. Calgary: Univeristy of Calgary, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Madhavanprabhakaran GK, Kumar KA, Ramasubramaniam S, et al. Effects of pregnancy related anxiety on labour outcomes: a prospective cohort study. J Nurs Midwifery Res 2013;2 10.14303/jrnm.2013.061 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38. UNICEF. Tanzania’s progress in maternal and child health. 2010. https://www.unicef.org/tanzania/6906_10741.html (accessed 1 Dec 2017).

- 39. Bayrampour H, Ali E, McNeil DA, et al. Pregnancy-related anxiety: a concept analysis. Int J Nurs Stud 2016;55:115–30. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2015.10.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Evans K, Spiby H, Morrell CJ. A psychometric systematic review of self-report instruments to identify anxiety in pregnancy. J Adv Nurs 2015;71:1986–2001. 10.1111/jan.12649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.