Abstract

Objective

This study aimed to elucidate the top five key priorities and barriers to chronic care in the health system of Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates (UAE).

Design

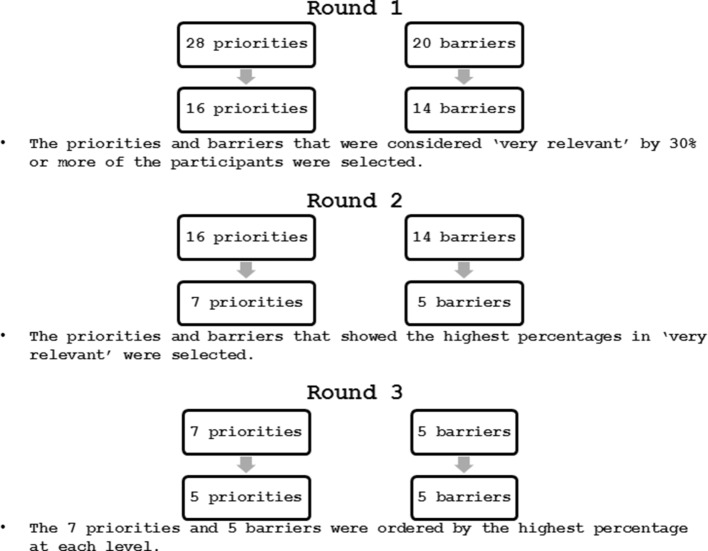

A modified Delphi study was performed to reach consensus on priority areas and barriers to the development of the Chronic Care Model in the health system of Abu Dhabi. Individual wireless audience response devices (keypads) linked to a computer were used to reduce 28 priorities and 20 barriers to the top five during three iterative rounds over three consecutive days.

Setting

Chronic care services for patients with diabetes, cardiovascular diseases and cancer, in both private and publicly funded healthcare services in the emirate of Abu Dhabi.

Participants

A purposive sample of 20 health systems’ experts were recruited. They were front-line healthcare workers from the public and private sector working in the delivery of care for patients with diabetes, cardiovascular diseases and cancer.

Results

The ‘overall organizational leadership in chronic illness care’ was ranked as the most important priority to address (26.3%) and ‘patient compliance’ was ranked as the most important barrier (36.8%) to the development of the Chronic Care Model.

Conclusions

This study has identified the current priorities and barriers to improving chronic care within Abu Dhabi’s healthcare system. Our paper addresses the UAE’s 2021 Agenda of achieving a world-class healthcare system, and findings may help inform strategic changes required to achieve this mission.

Keywords: health policy, organisation of health services, organisational development, international health services

Strengths and limitations of this study.

To our knowledge, this study is the first to use a modified Delphi technique to reach consensus on the health system in Abu Dhabi.

Use of the wireless computer-linked keypads ensured participant privacy and confidentiality during the consensus exercise.

A purposive sample of 20 front-line healthcare experts were chosen to represent the healthcare workers population providing daily care to chronic patients.

However, the sample was not a random sample; therefore, the results cannot be generalised.

Introduction

The Chronic Care Model (CCM) is a comprehensive model that integrates six elements to facilitate the delivery of high-quality care. Each element has its own strategic and developmental concepts to enhance the health outcomes of populations with chronic illness. This model was designed to help primary healthcare practices improve health outcomes by changing the routine of care delivery and to convert chronically ill patients from reactive to proactive in managing their own diseases.1 The CCM is a holistic combination of six elements combined to foster quality improvement in the following areas: health system, community, self-management support, decision support, delivery system design and clinical information systems. Increasing evidence has shown that changes in at least four of the six categories of the CCM led to clear advances in health outcomes.2 Some interventions have focused on one or two specific CCM components, and these studies also showed improvements in the development of the CCM.2 3 This model has been mostly applied to patients with diabetes, congestive heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, with evidence in the USA and Australia showing that patients benefited from healthcare adjustments guided by the CCM.1 4 5

A previous study (currently under review) conducted by our research group in the emirate of Abu Dhabi used the Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (ACIC) to understand the perception of healthcare workers on the development of the CCM in the delivery of chronic care to patients with diabetes, cardiovascular diseases and cancer. The study found that Abu Dhabi’s health system has reasonably good support for chronic illness care. It was a mixed-methods study comprising a quantitative and a qualitative part. The study participants scored the subcomponents of the CCM completing the ACIC and were asked about the subcomponents (priorities) of the CCM through a semistructured interview guide based on the ACIC. The priorities and barriers used in the present study emerged from an earlier work conducted by our research group.

Abu Dhabi is the largest emirate of the United Arab Emirates (UAE) in terms of territory and population. The UAE and emirate of Abu Dhabi have an unusual population pyramid, characterised by a young population and an imbalance in the sex ratio with approximately four times as many men as women.6 7 This disproportion of sex within the general population is due to the mass recruitment of expatriate men employed in the industrial and construction sector. However, there is an equal sex ratio between UAE nationals.6 In Abu Dhabi, only 18.2% of the residents are UAE nationals and the majority (67.3%) are under the age of 30 years.8 Although the UAE has a young population compared with similar high-income/developed countries, the UAE is facing the growing problem of chronic diseases related to lifestyle, that is, obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases and cancer. In 2016, the age-standardised prevalence of diabetes was 25.4% for UAE nationals and 15.2% for expats, and cardiovascular diseases accounted for 37.1% of all the deaths in the emirate.8 The UAE government has set health targets through the UAE Vision 2021. One of the key strategic goals of the UAE Vision 2021 National Agenda is to achieve a world-class healthcare system. Specific to chronic diseases this will be achieved by decreasing the prevalence of obesity among children, the overall prevalence of diabetes and the number of deaths from cardiovascular diseases.9 All seven UAE emirates (Abu Dhabi, Dubai, Sharjah, Ajman, Umm al Quwain, Ras Al-Khaimah and Fujairah) are working towards achieving these goals. The UAE healthcare system is regulated at both the federal and emirate levels, having multiple regulators and providers depending on the emirate.6 For these reasons, our study is focused on only one emirate, Abu Dhabi, and we used the CCM as a framework to improve chronic care. To our knowledge, this study is the first to address the CCM in the emirate of Abu Dhabi, and this framework may be useful in helping the UAE achieve a world-class health system as one of the key strategic goals of the UAE Vision 2021 National Agenda.

A modified Delphi technique was performed to identify and rank the top five priorities and barriers from an initial list of 28 priority areas and 20 barriers. The present study represents the first consensus exercise using a modified Delphi technique to identify the top five priorities and barriers to chronic care in the health system of Abu Dhabi, UAE.

Purpose and rationale

The main rationale of this study was the need to conduct the first consensus exercise with key stakeholders to understand the role of the CCM in UAE’s largest emirate—Abu Dhabi. The primary aim was to use a modified Delphi technique to identify and subsequently rank the priorities and barriers to the CCM in Abu Dhabi’s healthcare system (UAE). Using a health policy prioritisation approach to strengthen the health services requires proper and focused policymaking. Therefore, the modified Delphi technique sought to elucidate the five most significant priorities and barriers identified by participants that can be used to facilitate policymaking and healthcare reform in Abu Dhabi, UAE.

Prevention of bias

To maximise privacy and confidentiality, all participants were provided with an individual wireless keypad (Keepad Interactive, New South Wales, Australia) to electronically log their responses to each question and round of the Delphi study. Our study design maximises response rates and minimises missing data as the software displays the number of people who answered each question in the corner of the polling slide. The polling results for each question can be shown in real time to the participants; however, in this study, the participants did not receive any feedback until they were presented with the reduced list of priorities and barriers at the start of the subsequent round. The researchers conducting the modified Delphi technique did not have any conflicts of interest; hence, there was no need for an independent research team to coordinate the study. All the participants signed informed consent to be part of the study.

Reporting

Expert panel

A purposive sample of 20 front-line health systems’ experts on the Abu Dhabi emirate health system were recruited to perform the modified Delphi technique. These 20 participants were considered experts by their epistemic expertise, which was defined by Weinstein10 as ‘the capacity to provide strong justification for a range of propositions in a domain’. The following were the inclusion criteria to be considered as a health systems’ expert: works in the public or private sector of the healthcare system in Abu Dhabi; works in the same facility for more than 1 year; works in the delivery of care to patients with diabetes, cardiovascular diseases or cancer; and speaks and understands English. The participants were invited to attend three brief meetings to complete the three interactive rounds of the modified Delphi technique.

The majority of the participants were women (70%), nurses (37.5%), working in the public sector (70%) and in the Al Ain (eastern region) of Abu Dhabi (81.3%). The average years of experience was 14.8±13.7 and the mean working time in the same facility was 6.3±3.3 years.

Description of methods

The modified Delphi method itself starts with a series of questionnaires used to identify a list of topics. Through an interactive process of nominal scoring, the topics are reduced until a prespecified number of topics remain to be ranked in order of priority, and the process finishes when consensus has been established at a sufficient level.11 12 This technique supports health policy decision-making and has been used previously to reach expert consensus on definitions, guidelines and strategies for occupational health, elderly care, rural health, palliative care, primary healthcare, migrant health, diabetes and medical professionalism.10–19 This paper follows the recently published Guidelines to Conducting and REporting DElphi Studies.13

The study researchers printed sheets of A4 paper with the priorities and barriers, and these were provided to the participants on arrival. The research team also performed a pilot test of the Keepad computer software for the modified Delphi technique to ensure correct configuration and set-up of the wireless voting system through a PowerPoint presentation. The Keepad software has specific configurations for the type of question to be addressed and works as an interface with the wireless keypads. The participants used these individual computer-linked electronic keypads to vote and rank the priorities and barriers. The information provided from each wireless keypad was automatically logged on the computer system, and the results (ie, frequency and percentage) were provided immediately to the researchers. After each round, the researchers analysed the results to prepare the reduced list of tables and the PowerPoint presentation for the next round of the modified Delphi study.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and/or the public were not involved.

Procedure and definition of consensus

Three brief meetings were conducted to execute the three selection rounds and achieve consensus through this technique. Each of the three rounds was conducted over three separate consecutive days where the priorities and barriers were voted to reach the ‘top five’ by the end of the third meeting. At the start of each meeting, two coloured sheets with the priorities and barriers on a table with a 3-point Likert scale (yellow for priorities and blue for barriers) were given to the participants on arrival. The participants were asked to use the coloured sheets to score the priorities and barriers according to the provided 3-point Likert scale, ‘not very relevant’, ‘relevant’ or ‘very relevant’. Once all the participants had completed the Likert scale on the paper, wireless keypads were distributed and oral instructions about how to use them were given in order to record their answers. At the end of the first round, the researchers reviewed the results of each priority subcomponent and barrier that were voted ‘very relevant’, ‘relevant’ or ‘not very relevant’, according to participants’ previous handwritten choices (on the given coloured paper). The priorities and barriers that were considered ‘very relevant’ by at least 30% of the participants were selected for the next round. In this case, 28 priorities were reduced to 16 priorities, and 20 barriers were reduced to 14 barriers. During the second round, participants were asked to repeat the process and identify the five most relevant priorities and barriers by marking them as ‘very relevant’. The five priorities and barriers with the highest percentage of participants ranking them as ‘very relevant’ were selected to be ranked in the third round. Three of the priority subcomponents—‘Improvement strategy for chronic illness care’, ‘evidence-based guidelines’ and ‘patient treatment plans’—received the same proportion of votes. As a result of this tie, seven priorities were selected for the final ranking exercise in round 3 (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Delphi technique rounds procedure.

What are the top five priority areas to intervene?

Table 1 shows that 26.3% of expert participants selected the ‘overall organizational leadership in chronic illness care’ as the most important priority subcomponent of the CCM to address. The two subcomponents ‘continuity of care’ and ‘effective behavior change interventions and peer-support’ were voted as the second priority by 21.1% of the participants, leading to a tie in priority rank. The ‘evidence-based guidelines’ was voted as the third most important priority by 15.8% of the participants. The subcomponent ‘improvement strategy for chronic illness care’ was voted as the fourth most important priority by 10.5%, and the subcomponent ‘provider education for chronic illness care’ was voted as the fifth by 5.3% of the participants.

Table 1.

Round 3 results: top five priority subcomponents of the Chronic Care Model

| Rank | Percentage | Priorities |

| 1 | 26.3 | Overall organisational leadership in chronic illness care |

| 2 | 21.1 | Continuity of care |

| 2 | 21.1 | Effective behaviour change interventions and peer support |

| 3 | 15.8 | Evidence-based guidelines |

| 4 | 10.5 | Improvement strategy for chronic illness care |

| 5 | 5.3 | Provider education for chronic illness care |

What are the top five barriers to the development of the CCM?

‘Patient compliance’ was voted as the most important barrier to the development of the CCM by 36.8% of the participants. ‘Lack of standardized processes/procedures’ was voted as the second most important barrier by 31.6% of the participants, ‘differences between insurances’ was voted as the third most important barrier by 15.8% of the participants, ‘lack of regional plans and standardizing guidelines between facilities’ was voted as the fourth most important barrier by 10.5% of the participants, and ‘lack of monitoring’ was voted as the fifth most important barrier by 5.3% of the participants (table 2).

Table 2.

Round 3 results: top five barriers to the Chronic Care Model

| Rank | Percentage | Barriers |

| 1 | 36.8 | Patient compliance |

| 2 | 31.6 | Lack of standardised processes/procedures |

| 3 | 15.8 | Differences between insurances |

| 4 | 10.5 | Lack of regional plans standardising guidelines between facilities |

| 5 | 5.3 | Lack of monitoring |

Discussion

Our study used a modified Delphi technique to reach consensus on the priorities and barriers to the development of the CCM within Abu Dhabi’s health system. The CCM is composed of 6 elements with 28 subcomponents that the expert participants voted and ranked. The element ‘health system’ was present twice during the Delphi process in the subcomponents ‘overall organizational leadership in chronic illness care’ and ‘improvement strategy for chronic illness care’, while the elements ‘delivery system design’, ‘self-management’ and ‘decision support’ appeared once linked to the other subcomponents. The elements ‘clinical system design’ and ‘community’ were not represented in the final priorities.

The ‘overall organizational leadership in chronic illness care’ was the subcomponent ranked as the most important priority to address, relating to health system organisation and different leadership models. According to Lapão et al14, the development of a healthcare organisation is directly proportional to the leadership process, the professional’s management ability, the incentives and the resources available. The term ‘leadership’ is now a clearer concept; however, its operationalisation is still not mature and this may explain some of the difficulties acknowledged by health organisations.15 The highest ranked subcomponent (‘overall organizational leadership in chronic illness care’) is linked with the fourth ranked priority ‘improvement strategy for chronic illness care’. ‘Improvement strategy for chronic illness care’ addresses the need for healthcare system reorganisation to face the growing problem of chronic diseases. The development of the CCM advocates organisational changes in health delivery to a patient-centred model where the patient has a proactive role in managing their own disease. In the patient-centred model, all the providers are able to see patients’ information in their workstations and agree to follow the same guidelines and treatments with patients’ agreement.1 This example integrates four of the six elements of the CCM (delivery system design, clinical information system, decision support and self-management). ‘Continuity of care’ was ranked as the second most important priority, and it shows the perception of the experts on the need to change the delivery system design. In the Abu Dhabi health system, a patient is not allocated to a specific family medicine physician; the family medicine physician working at the chronic care clinics often does not follow the same patient every time, causing a lack of continuity of care from the perspective of the doctor–patient relationship. ‘Effective behavior change interventions and peer support’ was also ranked as the second most important priority. In the UK, Spain and Portugal, there is a general practitioner, or family medicine doctor, attributed to each person according to the residency area who acts as the first line of contact (or the ‘gatekeeper’) between the patient and the health system.16–18 This allows doctors to know their patients’ history (and families), establish a relationship with them and promote behaviour changes that are in the base of chronic disease prevention.17 ‘Evidence-based guidelines’ was considered the third most important priority to improve the care of chronic diseases in Abu Dhabi, however, the UAE was a pioneer in using evidence-based medicine, with the concept introduced in 1998.19 One of the reasons for this subcomponent to be ranked as a priority might be the multinational origin of the healthcare workforce, who tends to follow the guidelines of the country where they are from and/or trained. For example, physicians from North America may follow the North American guidelines related to a specific chronic disease. ‘Evidence-based guidelines’ is also related to electronic health records and decision-support systems that might help health professionals improve their performance, in terms of better decisions and time management.

‘Patient compliance’ was identified by the participants as the most important barrier. A study conducted in the Netherlands (2012) with the aim of understanding the development and coordination of disease management programmes also reported patients’ involvement in their own care as a barrier to implementing the CCM.20 From the literature, it is known that one way to address patient compliance is through patient education and participation.21 22 A ‘lack of standardized processes/procedures’ was considered to be the second most relevant barrier, and there is a need to integrate the delivery of care with the clinical systems for all professionals working in the health system. Also, this barrier seems to be related to the third ranked barrier: ‘differences between insurances’. Although health insurance is mandatory in the emirate of Abu Dhabi, there are different insurance packages depending on the type of employment, monthly income and residence visa. These different insurance packages provide access to different coverage plans and services. For example, diabetes education or lactation consultations are not available for patients with lower health insurance plans, which makes the delivery of care not standardised for the healthcare workers, as they are not able to provide the same procedure to all patients. The ‘differences between insurances’ was also considered a barrier by Haggstrom and colleagues23 when they assessed the CCM implementation for cancer screening in community centres in the USA.23 The ‘lack of regional plans standardizing the guidelines between the facilities’ was considered to be the fourth barrier. Abu Dhabi’s publicly funded health system seems to have a centralised organisational model where further work inside the organisation to engage top managers and healthcare workers is needed to understand why the same level of care following the same directions is not provided in all facilities. The barrier ranked as the fifth most important was ‘lack of monitoring’. This barrier is linked to the ‘lack of standardized processes/procedures’ and shows that healthcare workers and clinical directors feel the need for monitoring and feedback on their performance, interventions or implemented measures. These findings suggest that there is a need to examine the effectiveness and efficiency of the different communication channels, both horizontally and vertically, within an organisation. Soldberg and colleagues (2006) in the USA reported barriers related to ‘lack of monitoring’ when they implemented the CCM in a group of 18 clinics: insufficient time to measure the change, lack of measures to assess change, and a lack of specific details and desired care changes.24 It is hoped that our findings on the priorities and barriers to CCM implementation in the Abu Dhabi health system will contribute to the continuous improvement of the quality of healthcare delivery both for the patient and the healthcare workers. The UAE can serve as an example for other high-income and/or rapidly developing countries. The leadership stability, the availability and proper allocation of the resources, and the long-term economic and social strategies allowed the implementation of successful healthcare strategies creating an international competitive health system. To improve the delivery of care to chronic patients in the emirate of Abu Dhabi, the development of a healthcare strategy to achieve the UAE Vision 2021 is recommended. Based on the modified Delphi and the CCM premises, it would be recommended that a strategy includes the following:

Ongoing training for middle and executive managers on standardised leadership and communication skills.

Designing an appropriate improvement strategy for each healthcare service centre with the patient at the centre of care.

Implementing a general practitioner/family medicine physician model in healthcare centres in Abu Dhabi.

Ensuring the use of evidence-based guidelines.

Increasing the number of health educators to provide all patients with self-management support sessions to help them understand their proactive role in managing their own disease (‘how to comply’).

Healthcare facilities for types of insurances ensuring that healthcare workers can provide the highest level of standardised and quality care regardless of the patient’s health insurance (this already happens in some cases).

Establishing a monitoring process for healthcare workers with integrated feedback linked to team and facilities objectives (it is already used in some facilities in Abu Dhabi).

It is believed that these strategies can be applied to other health systems facing the same challenges of an ageing population coupled with high levels of lifestyle-related chronic diseases. Our findings also highlight some important concepts (continuity of care, differences between insurances) required to globally achieve universal health coverage.

Strengths

The wireless computer-linked keypads ensured participant privacy and confidentiality during the modified Delphi technique, and this should have minimised response bias. In addition, completing the study over three consecutive days, as opposed to weeks and months required with a postal or email methodology, resulted in a 95% response rate and a low attrition rate. Overall, our methodology using wireless handheld keypads enabled a rapid consensus process to effectively identify priorities and barriers to the CCM in Abu Dhabi’s health system. There are at least three previous studies that have used a Delphi technique in the UAE to reach consensus on occupational health,25 elderly care26 and medical professionalism26–28; however, our study is the first to use a modified Delphi technique to elucidate the priorities and barriers to the CCM in Abu Dhabi’s healthcare system.

Limitations

One of the limitations of this modified Delphi technique is the requirement for the participants to be physically present, which can introduce a selection bias if the attendance reduces significantly during the rounds.28 However, the response rate in this study was 95%, as from day 1 to the end of the study only one participant was absent; rounds 2 and 3 had 19 participants instead of 20. Our study specifically recruited expert front-line healthcare workers who delivered daily care to patients with chronic diseases. As such, the sample did not contain any executive healthcare leaders or policymakers, and future studies may want to consider conducting a Delphi study focusing on this group. Another limitation is the inability to generalise our results to the health systems operating in other emirates in the UAE; however, this was not the purpose of this study.

Adequacy of conclusions

The modified Delphi technique achieved the aim of identifying the priorities and barriers to the CCM in Abu Dhabi’s healthcare system; specifically, ‘Overall Organizational Leadership in Chronic Illness Care’ was ranked as the top priority and ‘Patient Compliance’ as the most important barrier. This study represents an important step in the process of understanding the key barriers and priority areas for interventions to maximise the development of the CCM in the health system of the Abu Dhabi emirate in the UAE.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the 20 health systems’ experts who participated in our study. Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia for funds to GHTM – UID/Multi/04413/2013

Footnotes

Contributors: MSP, TL and LVL designed the study. MSP and TL collected the data. MSP analysed the data and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. TL and LVL gave significant intellectual contributions to the final draft. All the authors critically read the content of this manuscript and approved this final version for publication.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by a competent ethical committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data available.

References

- 1. Coleman K, Austin BT, Brach C, et al. . Evidence on the Chronic Care Model in the new millennium. Health Aff 2009;28:75–85. 10.1377/hlthaff.28.1.75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wagner EH, Austin BT, Davis C, et al. . Improving Chronic Illness Care: Translating Evidence Into Action. Health Aff 2001;20:64–78. 10.1377/hlthaff.20.6.64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hung DY, Rundall TG, Tallia AF, et al. . Rethinking prevention in primary care: applying the chronic care model to address health risk behaviors. Milbank Q 2007;85:69–91. 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2007.00477.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Asch SM, Baker DW, Keesey JW, et al. . Does the collaborative model improve care for chronic heart failure? Med Care 2005;43:667–75. 10.1097/01.mlr.0000167182.72251.a1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Renders CM, Valk GD, Griffin SJ, et al. . Interventions to improve the management of diabetes in primary care, outpatient, and community settings: a systematic review. Diabetes Care 2001;24:1821–33. 10.2337/diacare.24.10.1821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Paulo MS, Loney T, Lapão LV. The primary health care in the emirate of Abu Dhabi: are they aligned with the chronic care model elements? BMC Health Serv Res 2017;17:725 10.1186/s12913-017-2691-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Koornneef E, Robben P, Blair I. Progress and outcomes of health systems reform in the United Arab Emirates: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res 2017;17:672 10.1186/s12913-017-2597-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Health Authority Abu Dhabi. Health Statistics 2016: Abu Dhabi, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Prime Minister’s Office. World-Class Healthcare | UAE Vision 2021. 2016. https://www.vision2021.ae/en/national-priority-areas/world-class-healthcare (accessed 8 Jan 2018).

- 10. Weinstein BD. What is an expert? Theor Med 1993;14:57–73. 10.1007/BF00993988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hsu C-C, Sandford B. The Delphi technique. Prat Assess Res Eval 2007;12:273–300. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lalloo D, Demou E, Kiran S, et al. . Core competencies for UK occupational health nurses: a Delphi study. Occup Med 2016;66:649–55. 10.1093/occmed/kqw089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jünger S, Payne SA, Brine J, et al. . Guidance on Conducting and Reporting Delphi Studies (CREDES) in palliative care: Recommendations based on a methodological systematic review. Palliat Med 2017;31:684–706. 10.1177/0269216317690685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lapão LV, Arcêncio RA, Popolin MP, et al. . Atenção Primária à Saúde na coordenação das Redes de Atenção à Saúde no Rio de Janeiro, Brasil, e na região de Lisboa, Portugal. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva 2017;22:713–24. 10.1590/1413-81232017223.33532016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lapão L, Dussault G. PACES: a national leadership program in support of primary-care reform in Portugal. Leadersh Heal Serv 2011;21:295–307. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Onion DK, Berrington RM. Comparisons of UK general practice and US family practice. J Am Board Fam Pract 1999;12:162–72. 10.3122/jabfm.12.2.162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Santos I, De QI, De DI, et al. . Indicadores de desempenho na consulta. Rev Port Med Geral e Fam 2009:227–35. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Silva Miguel L, Brito de Sa A, em C. Cuidados de Saúde Primários em 2011-2016: reforçar, expandir Contribuição para o Plano Nacional de Saúde 2011-2016. Lisboa: Alto Comissariado do Ministerio da Saude, 2010. http://1nj5ms2lli5hdggbe3mm7ms5.wpengine.netdna-cdn.com/files/2010/08/CSP1.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Al-Almaie SM, Al-Baghli NA. Evidence based medicine: an overview. J Family Community Med 2003;10:17–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kadu MK, Stolee P. Facilitators and barriers of implementing the chronic care model in primary care: a systematic review. BMC Fam Pract 2015;16:12 10.1186/s12875-014-0219-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Atreja A, Bellam N, Levy SR. Strategies to enhance patient adherence: making it simple. MedGenMed 2005;7:4 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16369309. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gold DT, McClung B. Approaches to patient education: emphasizing the long-term value of compliance and persistence. Am J Med 2006;119:S32–S37. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.12.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Haggstrom DA, Taplin SH, Monahan P, et al. . Chronic Care Model implementation for cancer screening and follow-up in community health centers. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2012;23:49–66. 10.1353/hpu.2012.0131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Solberg LI, et al. . Care Quality and Implementation of the Chronic Care Model: A Quantitative Study. The Annals of Family Medicine 2006;4:310–6. 10.1370/afm.571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lalloo D, Demou E, Kiran S, et al. . International perspective on common core competencies for occupational physicians: a modified Delphi study. Occup Environ Med 2016;73:452–8. 10.1136/oemed-2015-103285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Al Shemeili S, Klein S, Strath A, et al. . A modified Delphi study of structures and processes related to medicines management for elderly hospitalised patients in the United Arab Emirates. J Eval Clin Pract 2016;22:781–91. 10.1111/jep.12542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Abdel-Razig S, Ibrahim H, Alameri H, et al. . Creating a Framework for Medical Professionalism: An Initial Consensus Statement From an Arab Nation. J Grad Med Educ 2016;8:165–72. 10.4300/JGME-D-15-00310.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Aw TC, Loney T, Elias A, et al. . Use of an audience response system to maximise response rates and expedite a modified Delphi process for consensus on occupational health. J Occup Med Toxicol 2016;11:9 10.1186/s12995-016-0098-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.