Abstract

Antibiotics are essential treatments, especially in the developing world like World Health Organization (WHO) Southeast Asian region where infectious diseases are still the most common cause of death. In this part of the world, antibiotics are purchased and used without the prescription of a physician. Self-medication of antibiotics is associated with the risk of inappropriate drug use, which predisposes patients to drug interactions, masking symptoms of an underlying disease, and development of microbial resistance. Antibiotic resistance is shrinking the range of effective antibiotics and is a global health problem. The appearance of multidrug-resistant bacterial strains, which are highly resistant to many antibiotic classes, has raised a major concern regarding antibiotic resistance worldwide. Even after decades of economic growth and development in countries that belong to the WHO Southeast Asian region, most of the countries in this region still have a high burden of infectious diseases. The magnitude and consequence of self-medication with antibiotics is unknown in this region. There is a need for evidence from well-designed studies on community use of antibiotics in these settings to help in planning and implementing specific strategies and interventions to prevent their irrational use and consequently to reduce the spread of antibiotic resistance. To quantify the frequency and effect of self-medication with antibiotics, we did a systematic review of published work from the Southeast Asian region.

Keywords: antibiotics, self-medication, southeast asia

Introduction and background

Antibiotics are among the most commonly purchased drugs worldwide [1]. They are essential treatments, especially in the developing world where infectious diseases are still the most common cause of death [2]. Self-medication refers to the use of medicines to treat self-diagnosed disorders without consulting a medical practitioner and without any medical supervision [3]. It is a form of healthcare practiced in most parts of the world and overall 50% of total antibiotics used are purchased over-the-counter [4-5]. Repercussions of self-medication with antibiotics leading to health hazards, particularly in the developing world, are multifaceted as they are linked to poverty, inaccessibility, lack of medical professionals, poor quality of healthcare facilities, unregulated distribution of medicines, and patients’ misconceptions about physicians [6-7].

Self-medication of antibiotics is associated with the risk of inappropriate drug use, which predisposes patients to drug interactions, masking symptoms of an underlying disease, and the development of microbial resistance [8-9]. The inappropriate drug use practices common in self-medication include short duration of treatment, inadequate dose, sharing of medicines, and avoidance of treatment upon the improvement of disease symptoms [10]. The appearance of multidrug-resistant bacterial strains, which are highly resistant to many antibiotic classes, has raised a major concern regarding antibiotic resistance worldwide. This resistance may result in prolonged illnesses, more doctor visits, extended hospital stays, the need for more expensive medications, and even death [11].

Although various individual studies have examined antibiotic self-medication in countries that belong to the World Health Organization Southeast Asia region (WHO SEAR), there has not been a systematic review done in this setting. Even after decades of economic growth and development in countries that belong to the WHO SEAR, most of the countries in this region still have a high burden of infectious diseases [12]. There is a need for evidence from well-designed studies on the community use of antibiotics in these settings to help in planning and implementing specific strategies and interventions to prevent their irrational use and consequently to reduce the spread of antibiotic resistance. To quantify the frequency and effect of self-medication with antibiotics, we did a systematic review of published work from WHO SEAR.

Review

Methods

Search Strategy

Databases (PubMed, PubMed Central, and Google Scholar) were searched for peer-reviewed research published between January 2000 and January 2018. The search terms, viz. antimicrobial, antibiotics, antibacterial, self-medication, and non-prescription combined with the name of countries that belong to the WHO SEAR, were used. Medical subject headings (MeSH) of the search terms were used in each case to maintain common terms across all databases searched. A thorough review of the references revealed further relevant articles.

Selection Criteria

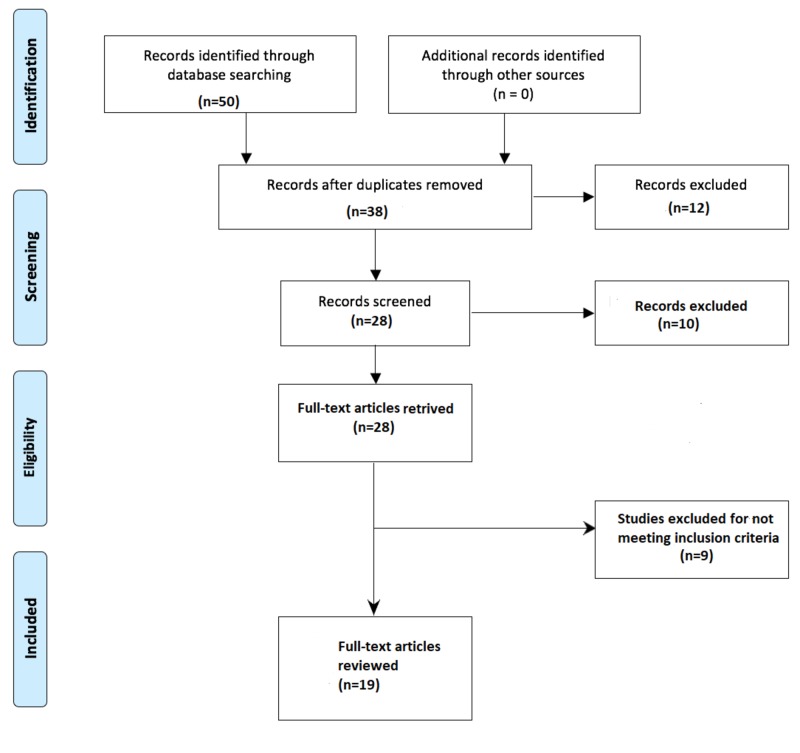

Studies published in the English language were included in the review if they aimed to assess self-medication of antibiotics in countries that belong to WHO SEAR. Studies on antivirals, antifungals, antiprotozoal, and topical antimicrobials were excluded. In addition, studies dealing with self-medication of overall drugs, editorials, correspondences, and letters to the editor were also debarred. A Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) diagram detailing the study identification and selection process is given in Figure 1.

Figure 1. PRISMA diagram detailing the study identification and selection process.

PRISMA: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

Data Abstraction

The authors screened the articles based on the inclusion/exclusion criteria. Full texts were obtained for articles that met inclusion criteria. Authors developed a data abstraction spreadsheet using Microsoft Excel version 2013 (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA) and included the following information: author, year of publication, journal, country where the study was done, recall period, study design, sample size, population sampled, prevalence of antimicrobial self-medication, type of antimicrobial agents used, source of drugs, disease symptoms, and inappropriate drug use practices.

Results

Study Selection

The initial electronic search identified 50 articles. After adjustment for duplicates, 38 remained. Of these, 10 studies were discarded, since, after review of their titles and abstracts, they did not meet the criteria. The full texts of the remaining 28 studies were reviewed in detail. Nine studies were cast away after the full text had been reviewed since they did not address much of the needed information. Finally, 19 studies were included in the review. A PRISMA diagram detailing the study identification and selection process is given in Figure 1.

Study Characteristics

Almost all 19 studies differed in their setting, recall period, sample size, and study subjects. The studies covered 11,197 participants and the sample size ranged from 110 to 2,996. All studies included in this review were cross-sectional surveys. The studies were performed in WHO SEAR (Bhutan, Bangladesh, India, Indonesia, South Korea, Nepal, Srilanka, and Thailand) and illustrated in Figure 2. No studies were available from three countries of WHO SEAR (Myanmar, Maldives, and Timor-Leste). The recall period used in data collection varied among the different studies, ranging from one month to one year. A recall period was not available for all included studies. Studies were conducted among the general public, university students, and medical professionals. A detailed description of the characteristics of individual studies is provided in Table 1.

Figure 2. Countries included in this study.

Table 1. Key Characteristics of Included Studies.

NA: not available; SMA: Self medication with antibiotics

| Study | Country | Year | Design | Recall time | Sample size | Subjects | SMA Prevalence (%) |

| Tshokey et al. [13] | Bhutan | 2017 | cross-sectional survey | NA | 692 | General public | 23.6% |

| Biswas et al. [14] | Bangladesh | 2014 | cross-sectional survey | 3 months | 1300 | General public | 26.69% |

| Seam et al. [15] | Bangladesh | 2018 | cross-sectional survey | NA | 250 | Pharmacy students | 15.6% |

| Shubha et al. [16] | India | 2013 | cross-sectional survey | NA | 110 | Dentists | 78.18% |

| Biswas et al. [17] | India | 2015 | cross-sectional survey | 6 months | 164 | Nursing students | 54.2% |

| Nair et al. [18] | India | 2015 | cross-sectional survey | 1 year | 221 | Medical students | 85.59% |

| Ahmad et al. [19] | India | 2012 | cross-sectional survey | NA | 600 | General public | 33.5% |

| Pal et al. [20] | India | 2016 | cross-sectional survey | NA | 216 | Medical and pharmacy students | 75% |

| Virmani et al. [21] | India | 2017 | cross-sectional survey | 1 years | 456 | Health science students | 60% |

| Ganesan et al. [22] | India | 2014 | cross-sectional survey | NA | 781 | General public | 39.4% |

| Widayati et al. [23] | Indonesia | 2011 | cross-sectional survey | 1 month | 559 | General public | 7.3% |

| Hadi et al. [24] | Indonesia | 2008 | cross-sectional survey | 1 month | 2996 | General public | 16% |

| Kurniawan et al. [25] | Indonesia | 2015 | cross-sectional survey | 6 months | 400 | General public | 45% |

| Kim et al. [26] | Korea | 2011 | cross-sectional survey | NA | 1,177 | General public | 46.9% |

| Sah et al. [27] | Nepal | 2016 | cross-sectional survey | NA | 327 | Nursing students | 50.7% |

| Pant et al. [28] | Nepal | 2015 | cross-sectional survey | 1 year | 168 | Dental students | 35.1% |

| Banerjee et al. [29] | Nepal | 2016 | cross-sectional survey | NA | 488 | Medical students | 26.2% |

| Rathish et al. [30] | Sri Lanka | 2017 | cross-sectional survey | 1 month | 696 | Medical students | 39% |

| Sirijoti et al. [31] | Thailand | 2014 | cross-sectional survey | 3 months | 396 | General public | 37.37% |

Prevalence of Self-Medication

The prevalence of self-medication with antibiotics (SMA) ranged from 7.3% to 85.59% with an overall prevalence of 42.64%. Prevalence rates differed greatly between countries and study subjects, as is summarized in Table 1. A high prevalence was reported from India and Nepal, and a low prevalence was reported from Indonesia and Bangladesh. The prevalence of SMA was higher among men in most studies. The prevalence of SMA was higher among health students and health professionals and was low among the general public.

Common Illnesses and Reasons that Led to Self-Medication

The common cold, sore throat, fever, gastrointestinal tract diseases, and respiratory diseases were the commonest illnesses or symptoms for which self-medication was taken. The major reasons behind the frequent practice of SMA were prior experiences of treating a similar illness, ignorance regarding the seriousness of the disease, an assured feeling of not requiring a visit to the physician, less expensive and easily affordable in terms of time and money, knowledge of the antibiotics, and suggestions from others. Table 2 shows the illnesses that resulted in self-medication and the reasons that drove people to practice self-medication as reported in each study.

Table 2. Illnesses and Reasons for Self-medication with Antibiotics .

NA: not available; OPD: outpatient department; GIT: gastrointestinal tract

| Study | Illnesses | Reasons |

| Tshokey et al. [13] | NA | NA |

| Biswas et al. [14] |

|

|

| Seam et al. [15] | NA |

|

| Shubha et al. [16] |

|

|

| Biswas et al. [17] |

|

NA |

| Nair et al. [18] |

|

|

| Ahmad et al. [19] |

|

|

| Pal et al. [20] |

|

|

| Virmani et al. [21] |

|

NA |

| Ganesan et al. [22] |

|

NA |

| Widayati et al. [23] | Common-cold, including cough, sore throat, headache, and other minor symptoms |

|

| Hadi et al. [24] | NA | NA |

| Kurniawan et al. [25] |

|

|

| Kim et al. [26] | NA | NA |

| Sah et al. [27] |

|

|

| Pant et al. [28] | Fever (39.0%) followed by sore throat, cough, diarrhoea, and runny nose |

|

| Banerjee et al. [29] | NA | NA |

| Rathish et al. [30] |

|

|

| Sirijoti et al. [31] | NA |

|

Source of Medicines

The majority of the antimicrobial drugs used in self-medication were obtained from various sources, such as pharmacies, leftover drugs, hospitals, and from friends and family. The use of self-medication was commonly suggested by pharmacy professionals, friends, family, and relatives among the general public, whereas among health students and health professionals, self-medication was because of knowledge of medicine and pharmacology.

Antibiotics Used in Self-Medication

The most common antibiotic used for self-medication was amoxicillin, followed by macrolides, fluoroquinolones, cephalosporins, and metronidazole [14, 16-25, 27-30]. Antibiotics used for self-medication in each of the included studies are given in Table 3. Of the 19 studies included in the review, four did not investigate the types of antibiotics used in self-medication [13, 15, 26, 31]. Among the macrolides, azithromycin use was most common, and among the fluoroquinolones, ciprofloxacin use was most common.

Table 3. Antibiotics Used in Self-medication, Inappropriate Use, and Source.

NA: not available

| Study | Inappropriate drug use | Most common antibiotics used | Source of drugs |

| Tshokey et al. [13] |

|

NA | NA |

| Biswas et al. [14] | NA |

|

Pharmacies |

| Seam et al. [15] | NA | NA | Pharmacies |

| Shubha et al. [16] |

|

|

Medicine at home/clinic |

| Biswas et al. [17] | NA |

|

|

| Nair et al. [18] | NA |

|

|

| Ahmad et al. [19] | NA |

|

|

| Pal et al. [20] | Only 72.2% of medical students and 33.3% of pharmacy students took full course of antibiotics |

|

NA |

| Virmani et al. [21] | Very few completed the course once started |

|

NA |

| Ganesan et al. [22] | NA |

|

|

| Widayati et al. [23] | NA |

|

|

| Hadi et al. [24] | NA |

|

|

| Kurniawan et al. [25] | NA |

|

|

| Kim et al. [26] | 77.6% of respondents stopped taking the medication when they felt better | NA | NA |

| Sah et al. [27] | NA |

|

NA |

| Pant et al. [28] |

|

|

Pharmacies |

| Banerjee et al. [29] | NA |

|

Pharmacies |

| Rathish et al. [30] | NA |

|

|

| Sirijoti et al. [31] |

|

NA |

|

Inappropriate Use of Antibiotics

Only seven studies included in the review reported the inappropriate use of antibiotics [13, 16, 20-21, 26, 28, 31]. The most inappropriate practice was an abrupt stoppage of the antibiotic course after the disappearance of symptoms. Other improper practices were sharing antibiotics, saving antibiotics for future use, and switching antibiotics if symptoms were not relieved.

Discussion

The main finding of this review is that there are many published studies to indicate that the prevalence of SMA is alarmingly high among member countries of WHO SEAR. The prevalence of self-medication varied across the studies reviewed, ranging from 7.3% to 85.59%, with an overall prevalence of 42.64%. The main reasons for the wide variation in the prevalence of the self-medication practice may be differences in social determinants of health, tradition, culture, economic status, and developmental status. The difference in methodology, study setting, sample population, and recall time may also have contributed to this variation in prevalence of self-medication. A systematic review by Alhomoud et al. reported that the overall prevalence of self-medication varied from 19% to 82% in the Middle East [32]. A similar review by Ayalew et al. found that the prevalence of self-medication varied across the studies, ranging from 12.8% to 77.1% in Ethiopia [33]. The results of the current review are similar to those reported for SMA in the Euro-Mediterranean region [34] and developing countries [35]; the overall median proportions of self-medication reported for these countries were 40.9% and 38.8%, respectively. Developed countries, such as those of Europe where over-the-counter antibiotic sales are strictly regulated, have much lower prevalence rates of SMA, ranging from 1% to 4% [36].

Comparatively, higher self-medication use was reported in studies conducted on health science students than the general public. This may be because of the better understanding of disease and drugs leading to a decreased inclination towards seeking physicians’ help to treat their illnesses. Other studies conducted on health science students in different parts of the world have also reported a higher prevalence of self-medication practice [37-38]. Previous experience of treating a similar illness, feeling that the illness was mild and did not require the service of a physician, less expensive in terms of time and money, gaps in terms of knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding antibiotic use, such as keeping leftover antibiotics for future use, sharing antibiotics with others, and belief that antibiotics can speed up recovery and eradicate any infection, were the most common reasons for SMA among the general public.

This review found that the main source of antibiotics used for self-medication were pharmacies, followed by friends and family. Pharmacists often do not have an adequate knowledge of the antimicrobial agents and the disease processes. However, they are commonly preferred as a source of advice or information for the antimicrobial agents obtained and used over-the-counter. Thus, pharmacists could play an important role in educating patients, rationalizing antibiotic use, and stopping antibiotic sales without a prescription.

Settings in which individuals are highly educated tend to have relatively low levels of use of antimicrobial self-medication. Therefore, awareness among communities is an important target to minimize antimicrobial self-medication in WHO SEAR. Due to their prior successful use of antimicrobial agents, individuals in most communities tend to believe that they can manage subsequent illnesses without consulting a physician. This is a potential risk factor for inappropriate drug use since most patients lack knowledge of the disease process and the medicines used in self-medication. The reasons for self-medication with antibiotics are different according to settings and are due to the complex network of a poor health system, social, economic, and health factors [39]. Therefore, establishing these factors is of paramount importance in designing and implementing programs against self-medication with antibiotics.

The underlying challenges of health systems in most countries of WHO SEAR, such as inadequate healthcare, potentially influence the use of self-medication [39]. In addition, the lack of policies or their inadequate implementation enables easy over-the-counter access of antibiotics [40]. Furthermore, most developing countries face the challenge of an irregular supply of drugs to the public health facilities, which limits community access to healthcare. This, coupled with the high burden of infectious diseases in these countries, makes the private sector an important alternative source of healthcare [41].

The common cold, sore throat, fever, gastrointestinal tract diseases, and respiratory diseases were the commonest illnesses or symptoms for which self-medication was taken. Fever and cold were indicated as the most frequent health complaint that led to self-medication in different studies [42-43]. There were also studies that reported respiratory diseases [44] and gastrointestinal (GI) tract diseases [45] as common illnesses for which self-medication was used. This may be because these illnesses are very common and occur frequently in individuals with experience in treating them. The mild and self-limiting nature of these illnesses may also prevent patients from seeking physician consultation. However, patients should not forget that when these illnesses/symptoms occur repeatedly or for prolonged periods, they should be investigated further by physicians, as they may be manifestations of serious illnesses.

Self-medication with antibiotics occurred with different antibiotic classes. The most common antibiotics used for self-medication was amoxicillin, followed by macrolides, fluoroquinolones, cephalosporins, and metronidazole. The high use of amoxicillin and fluoroquinolones may be due to the low cost, easy availability, and low side effect profiles. Amoxicillin, fluoroquinolones, and macrolides are also the most commonly prescribed antibiotics in this region and patients tend to use these prescriptions as a reference for similar illness in future [46-47]. Amoxicillin is a useful first-line antibiotic for acute otitis media, pneumonia, urinary tract infections, and other infections. Rampant, irrational use leads to resistance and treatment failure. Drugs from the quinolone group of antibiotics are reserved as second-line drugs for tuberculosis. Self-medication and inappropriate use of ciprofloxacin make people vulnerable to drug-resistant tuberculosis.

The review established an inappropriate practice of antibiotic self-medication in communities of WHO SEAR. The most common inappropriate practice was an abrupt stoppage of a course of antibiotics after the disappearance of the symptoms. Another inappropriate practice was sharing antibiotics, saving antibiotics for future use, and switching antibiotics if symptoms were not relieved. However, the clinical outcomes of antibiotic self-medication were rarely reported in the articles from most studies in the WHO SEAR, probably because of a lack of awareness about the potentially harmful effects of antibiotics. These inappropriate uses potentially increase the risk of mistreatment, adverse drug reactions, drug interactions, and the development of resistance.

Some studies included in the review reported self-medication using multiple antimicrobial agents. The use of more than one antibiotic during an illness episode is indicative of the uncertainty of the cause of illness. These inappropriate practices potentially increase the risk of mistreatment, adverse drug reaction, development of resistance and drug interactions [8, 41]. This is further worsened by the high burden of infectious diseases in addition to the limited therapeutic choices in most WHO Southeast Asian countries [41]. Antibiotic resistance is likely to add further financial strains to the healthcare system, which currently is already facing the challenge of inadequate funding. This is especially the case as patients with resistant infections are likely to stay longer in hospitals and there is a need for more expensive second-line antibiotics. Agencies, such as the World Health Organization (WHO), the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC), the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), and the Ministry of Health of countries belonging to WHO SEAR, need to establish specific interventions focusing on these common inappropriate antibiotic use practices.

Thus, the situation can be changed in the WHO SEAR by enforcing and controlling laws and regulations related to the antibiotic dispensation in pharmacies and by increasing public awareness about the adverse drug reactions, development of superinfections, and antibiotic-resistance. These problems require appropriate measures by policymakers to develop pertinent policies, as well as to ensure their implementation.

Conclusions

The prevalence of SMA is comparatively high in the countries of WHO SEAR and is marked with inappropriate use of drugs, which is the leading cause of antibiotic resistance. Educational interventions targeting the general public, pharmacists, and healthcare students are of utmost importance. In addition, the improvement in the quality of healthcare facilities with easy access, law enforcement, and control regulations regarding the inappropriate use of antibiotics closely collaborating with public awareness about antibiotic resistance could alleviate and, ultimately, eradicate the challenge of SMA in this region. Since many patients get knowledge about drugs from the previous prescriptions, physicians should limit superfluous prescriptions of antibiotics and implement guideline-based practices. Pharmacists should also be morally encouraged to educate patients and rationalize antibiotic use by strictly stopping antibiotic sales without an authorized prescription by physicians.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dhiraj Poudel, Prakriti Regmi, Om Prakash Bhatta, and Siddhartha Bhandari for proofreading this article.

The content published in Cureus is the result of clinical experience and/or research by independent individuals or organizations. Cureus is not responsible for the scientific accuracy or reliability of data or conclusions published herein. All content published within Cureus is intended only for educational, research and reference purposes. Additionally, articles published within Cureus should not be deemed a suitable substitute for the advice of a qualified health care professional. Do not disregard or avoid professional medical advice due to content published within Cureus.

Footnotes

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

References

- 1.Estimating worldwide current antibiotic usage: report of Task Force 1. Col NF, O'Connor RW. Rev Infect Dis. 1987;9:0–43. doi: 10.1093/clinids/9.supplement_3.s232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Health Organization. Geneva : World Health Organization: [Mar;2018 ]. 2008. Health statistics and information systems. The global burden of disease: 2004 Update. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Geneva : World Health Organization. Geneva : World Health Organization: [Mar;2018 ]. 2000. Guidelines for the regulatory assessment of medicinal products for use in self-medication. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Antibiotic use worldwide . Högberg LD, Muller A, Zorzet A, et al. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14:1179–1180. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70987-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Non-prescription antimicrobial use worldwide: A systematic review . Morgan DJ, Okeke IN, Laxminarayan R, et al. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011;11:692–701. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70054-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Antimicrobial resistance in developing countries. Hart CA, Kariuki S. BMJ. 1998;317:647–650. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7159.647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Antibiotic use in developing countries. Istúriz RE, Carbon C. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2000;21:394–397. doi: 10.1086/501780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization. Geneva : World Health Organization. Geneva : World Health Organization: [Mar;2018 ]. 2009. Community-Based Surveillance of Antimicrobial Use and Resistance in Resource-Constrained Settings: Report on Five Pilot Projects. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malaria deaths as sentinel events to monitor healthcare delivery and antimalarial drug safety. Mehta U, Durrheim DN, Blumberg L, et al. Trop Med Int Health. 2007;12:617–628. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2007.01823.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Self-medication with antibiotics in rural population in Greece: a cross-sectional multicenter study. Skliros E, Merkouris P, Papazafiropoulou A, et al. BMC Fam Pract. 2010;11:58. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-11-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The epidemic of antibiotic resistant infections: A call to action for the medical community from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Spellberg B, Guidos R, Gilbert D, et al. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:155–164. doi: 10.1086/524891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Communicable diseases in the South-East Asia Region of the World Health Organization: towards a more effective response . Gupta I, Guin P. http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/88/3/09-065540. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88:199–205. doi: 10.2471/BLT.09.065540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Assessing the knowledge, attitudes, and practices on antibiotics among the general public attending the outpatient pharmacy units of hospitals in Bhutan: a cross-sectional survey. Tshokey T, Adhikari D, Tshering T, et al. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2017;29:580–588. doi: 10.1177/1010539517734682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Self medicated antibiotics in Bangladesh: a cross-sectional health survey conducted in the Rajshahi City. Biswas M, Roy MN, Manik MI, et al. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:847. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Assessing the perceptions and practice of self-medication among Bangladeshi undergraduate pharmacy students. Seam MO, Bhatta R, Saha BL, et al. Pharmacy (Basel) 2018;6:0. doi: 10.3390/pharmacy6010006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Self-medication pattern among dentists with antibiotics. Shubha R, Savkar MK, Manjunath GN. http://www.jemds.com/data_pdf/2_subha%20praveen%20-.pdf J Evol Med Dent Sciences. 2013;2:9037–9041. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Self-medication with antibiotics among undergraduate nursing students of a government medical college in Eastern India. Biswas S, Ghosh A, Mondal K, et al. http://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/b67a/839b970cfdb525097f1534801e85485fa10f.pdf IJPR. 2015;5:239–243. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pattern of selfmedication with antibiotics among undergraduate medical students of a government medical college. Nair A, Doibale MK, Kulkarni SK, et al. http://cdn.ijpphs.com/Upload/iphhs_1_3_oa_02.pdf Int J Prev Public Health Sci. 2015;1:9–13. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Evaluation of self-medication antibiotics use pattern among patients attending community pharmacies in rural India, Uttar Pradesh. Ahmad A, Parimalakrishnan S, Patel I, et al. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/233980341_Evaluation_of_Self-Medication_Antibiotics_Use_Pattern_Among_Patients_Attending_Community_Pharmacies_in_Rural_India_Uttar_Pradesh J Pharm Res. 2012;5:765–768. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Self medication with antibiotics among medical and pharmacy students in North India. Pal B, Murti K, Gupta AK, et al. Curr Res Med. 2016;7:7–12. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Antibiotic use among health science students in an Indian university: A cross sectional study. Virmani S, Nandigam M, Kapoor B, et al. Clin Epidemiol Glob Health. 2017;5:176–179. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Self-medication and indiscriminate use of antibiotics without prescription in Chennai, India: a major public health problem. Ganesan N, Subramanian S, Jaikumar RH, et al. https://www.scribd.com/document/256132947/Self-Medication-and-indiscriminate-use-of-antibiotics-without-Prescription-in-Chennai-India-A-Major-Public-Health-Problem J Club Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2014;1:131–141. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Self medication with antibiotics in Yogyakarta City Indonesia: a cross sectional population-based survey. Widayati A, Suryawati S, de Crespigny C, Hiller JE. BMC Res Notes. 2011;4:491. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-4-491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Survey of antibiotic use of individuals visiting public healthcare facilities in Indonesia. Hadi U, Duerink DO, Lestari ES, et al. Int J Infect Dis. 2008;12:622–629. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Association between public knowledge regarding antibiotics and self-medication with antibiotics in Teling Atas Community Health Center, East Indonesia. Kurniawan K, Posangi J, Rampengan N. http://mji.ui.ac.id/journal/index.php/mji/article/download/1589/1168 Med J Indonesia. 2017;26:62–69. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Public knowledge and attitudes regarding antibiotic use in South Korea. Kim SS, Moon S, Kim EJ. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2011;41:742–749. doi: 10.4040/jkan.2011.41.6.742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Self-medication with antibiotics among nursing students of Nepal . Sah AK, Jha RK, Shah DK. http://www.ijpsr.info/docs/IJPSR16-07-11-001.pdf IJPSR. 2016;7:427–430. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Self-medication with antibiotics among dental students of Kathmandu - prevalence and practice. Pant N, Sagtani RA, Pradhan M, et al. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/304571326_Self-medication_with_antibiotics_among_dental_students_of_Kathmandu_-_Prevalence_and_Practice Nepal Med Coll J. 2015;17:47–53. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Self-medication practice among preclinical university students in a medical school from the city of Pokhara, Nepal. Banerjee I, Sathian B, Gupta RK, et al. Nepal J Epidemiol. 2016;6:574–581. doi: 10.3126/nje.v6i2.15165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pharmacology education and antibiotic self-medication among medical students: a cross-sectional study. Rathish D, Wijerathne B, Bandara S, et al. BMC Res Notes. 2017;10:337. doi: 10.1186/s13104-017-2688-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Assessment of knowledge attitudes and practices regarding antibiotic use in Trang province, Thailand. Sirijoti K, Hongsranagon P, Havanond P, et al. http://www.jhealthres.org/upload/journal/729/28(5)_kanjanachaya_p299-307.pdf J Health Res. 2014;28:299–307. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Self-medication and self-prescription with antibiotics in the Middle East—do they really happen? A systematic review of the prevalence, possible reasons, and outcomes. Alhomoud F, Aljamea Z, Almahasnah R, et al. Int J Infect Dis. 2017;57:3–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2017.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Self-medication practice in Ethiopia: a systematic review. Ayalew MB. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2017;11:401–413. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S131496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Self-medication with antibiotics in the ambulatory care setting within the Euro-Mediterranean region; results from the ARMed project. Scicluna EA, Borg MA, Gür D, et al. J Infect Public Health. 2009;2:189–197. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Household antimicrobial self-medication: a systematic review and metaanalysis of the burden, risk factors and outcomes in developing countries. Ocan M, Obuku EA, Bwanga F, et al. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:742. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2109-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Self-medication with antimicrobial drugs in Europe. Grigoryan L, Haaijer-Ruskamp FM, Burgerhof JG, et al. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16704784. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:452–459. doi: 10.3201/eid1203.050992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Prevalence of self medication among the pharmacy students in Guntur: a questionnaire based study. Bollu M, Vasanthi B, Chowdary PS, et al. http://www.wjpps.com/wjpps_controller/abstract_id/2374 World J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2014;3:810–826. [Google Scholar]

- 38.A cross-sectional study on knowledge, attitude and behavior related to antibiotic use and resistance among medical and non-medical university students in Jordan. Suaifan G, Shehadeh M, Darwish D, et al. http://www.academicjournals.org/journal/AJPP/article-full-text-pdf/A777AD433806 Afr J Pharm Pharmacol. 2012;6:763–770. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Improving antibiotic use in low-income countries: an overview of evidence on determinants. Radyowijati A, Haak H. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57:733–744. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00422-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.World Health Organization. The World Medicines Situation Geneva Switzerland: WHO. Geneva: World Health Organization: [Mar;2018 ]. 2011. The World Medicines Situation Report 2011. Medicine Expenditures. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Antimicrobial resistance in developing countries. Part II: strategies for containment. Okeke IN, Klugman KP, Bhutta ZA, et al. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5:568–580. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(05)70217-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Evaluation of self-medication practices in acute diseases among university students in Oman. Flaiti MA, Badi KA, Hakami WO, et al. J Acute Dis. 2014;3:249–252. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Assessment of self-medication practices among medical, pharmacy and nursing students at a tertiary care teaching hospital. Gaddam D. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Damodar_Gaddam/publication/230779793_Assessment_of_Self-medication_Practices_among_Medical_Pharmacy_and_Nursing_Students_at_a_Tertiary_Care_Teaching_Hospital/links/09e415045784f24421000000/Assessment-of-Self-medication-Practices-among-Medical-Pharmacy-and-Nursing-Students-at-a-Tertiary-Care-Teaching-Hospital.pdf Indian J Hosp Pharm. 2012;49:79–83. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Self-medication practice among Iraqi patients in Baghdad city. Jasim AL, Fadhil TA, Taher SS. http://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/b069/62ba8a86c8443578e73e1ffec225d3faa93c.pdf Am J Pharmacol Sci. 2014;2:18–23. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Medication storage and self-medication behaviour amongst female students in Malaysia. Ali SE, Ibrahim MI, Palaian S. http://scielo.isciii.es/pdf/pharmacy/v8n4/original3.pdf. Pharm Pract (Granada) 2010;8:226–232. doi: 10.4321/s1886-36552010000400004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Prescribing pattern of antibiotics in patients attending ENT OPD in a tertiary care hospital. Vanitha M, Vineela M, Benjamin RKP, et al. http://www.iosrjournals.org/iosr-jdms/papers/Vol16-issue9/Version-2/H1609023033.pdf IOSR-JDMS. 2017;16:30–33. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Trends in prescribing antimicrobial in an ENT outpatients department of tertiary care hospital for upper respiratory tract infection. Ramchandra K, Sanji N, Somashekar H S, et al. https://www.ijpcs.net/sites/default/files/IJPCS_1_1_04.pdf Int J Pharmacol and Clin Sci. 2012;1:15–18. [Google Scholar]