Abstract

Enamel, dentin and cementum are dental tissues with distinct functional properties associated with their unique hierarchical structures. Some potential ways to repair or regenerate lost tooth structures have been revealed in our studies focused on examining teeth obtained from mice with mutations at the mouse progressive ankylosis (ank) locus. Previous studies have shown that mice with such mutations have decreased levels of extracellular inorganic pyrophosphate (PPi) at local sites resulting in ectopic calcification in joint areas and in formation of a significantly thicker cementum layer when compared with age-matched wild-type (WT) tissue [1, 2]. As a next step, to determine the quality of the cementum tissue formed in mice with a mutation in the ank gene (ank/ank), we compared the microstructure and mechanical properties of cementum and other dental tissues in mature ank/ank vs. age-matched WT mice. Backscattered scanning electron microscopy (SEM) imaging and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analyses on mineralized tissues revealed no decrease in the extent of mineralization between ank/ank cementum vs. WT controls. Atomic-force-microscopy-based nanoindentation performed on enamel, dentin or cementum of ank/ank vs. age-matched WT molars revealed no significant difference in any of the tested tissues in terms of hardness and elastic modulus. These results indicate that the tissue quality was not compromised in ank/ank mice despite faster rate of formation and more abundant cementum when compared with age-matched WT mice. In conclusion, these data suggest that this animal model can be utilized for studies focused on defining mechanisms to promote cementum formation without loss of mechanical integrity.

Keywords: Cementum, Phosphate, Pyrophosphate, ank, Structure, Nanoindentation

Introduction

Periodontal diseases are one of the major causes of tooth loss [3, 4]. Current clinical strategies for periodontal repair involve use of scaffolds and putative regenerative factors, or extraction of diseased teeth with replacement by implants or removable/fixed prostheses [5, 6]. Although these strategies have some positive outcomes, treatments using scaffolds/regenerative factors are often not predictable while replacement therapies often require several additional procedures to further augment supporting tissues, and esthetic outcomes may not be ideal. One approach to developing therapies that are more predictable and robust than the existing ones is to understand the regulators controlling cementum formation. Toward this goal, our laboratory has reported enhanced cementum formation in teeth from ank/ank mice when compared with teeth obtained from wild-type (WT) mice. This finding has lead us to focus on understanding phosphate metabolism as a means of controlling or promoting mineralization without the loss of function [7-10].

Pyrophosphate (PPi) is an inhibitor of mineralization and is most widely known for its function(s) in bone mineralization. The PPi is synthesized through phosphohydrolysis of ATP and nucleoside triphosphote by nucleotide pyrophosphatase phosphodiesterase (NPP) ectoenzymes such as PC-1 and B10 [10]. The transfer of PPi to the cell exterior is mediated by the ANK protein at the cell membrane [1]. Experimental and clinical evidence points to low levels of extracellular PPi, due to either a decrease in production of PPi or poor channeling of PPi through the cell membrane to the extracellular matrix, as a cause of pathological calcification. For example, ectopic calcification on articular surfaces has been reported in mice with mutations in either Ank or Enpp1 (PC-1 expressing gene) [1]. Interestingly, we recently reported that teeth obtained from mice with either PC-1 or ank mutations, i.e. low levels of ePPi, exhibited a ten fold increase in cementum formation compared to teeth from WT counterparts, with no observable ectopic calcification in the periodontal ligament (PDL) or differences in the surrounding alveolar bone or underlying dentin [2]. These findings offer encouragement for the use of factors regulating Pi/PPi levels to promote cementum regeneration providing that both the structural and mechanical integrity of the newly formed cementum is not compromised. To address this issue we performed electron microscopy and nanoindentation to correlate the structural and mechanical properties of the newly formed cementum in teeth obtained from ank/ank mice.

The technique of nanoindentation has been widely utilized in analyzing mechanical properties of bone and dental tissues [11-13] Using this technique, with proper surface preparation, one can map mechanical properties of mineralized tissues with high spatial resolution, micron or sub-micrometer, defined by the vertical indentor used in such an approach. This technique has been used to map the mechanical properties of dentin-enamel junction in human teeth with spatial resolution as high as 1 μm, revealing the mechanically graded nature of this transitional zone [14]. Ho et al mapped the mechanical properties of apical dentin-cementum junction in human molars and identified a transition zone at this junction, with nanomechanical properties from different either dentin or cementum [14]. In addition, the use of nanoindentation has continued to provide unique information on small scale variations in mechanical properties within dentin and enamel, as well as mechanical property changes in dental tissues due to environmental effects [15-23]. Given the high spatial resolution provided and the recent proven success in characterizing dental tissues, the technique of nanoindentation was chosen to characterize the mechanical properties of the 1st mandibular molar obtained from ank/ank mice in this work. In addition, SEM and TEM were used to compare the structural variations and mineral chemistry of dental tissues of ank/ank mice to that of age-matched wild type mice. Below, we describe our findings in detail that demonstrate, based on the parameters used here, that the cementum formed on tooth roots in ank/ank mice exhibits the same properties as cementum in wild type mice.

Materials & Methods

Mouse Breeding and Tissue Extraction/Storage

Wild type and homozygote ank/ank mutant mice were employed for this study. Breeder pairs (heterozygote x heterozygote) of ank mutant mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA) with the genotype characterized according to the protocol described in Nociti et al [1]. All procedures were approved by the University of Washington Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. The 100 day old lower left mandibles were extracted from 6 wild-type (WT) and 5 ank/ank animals and stored in PBS buffer supersaturated with calcium phosphate and thymol at 4°C until characterization by microscopy or nanoindentation was carried out.

Mechanical Properties - Nanoindentation

The sample preparation for nanoindentation involved mounting lower left mandibles in room-temperature-cure epoxy (Allied High Tech Products, Inc., Rancho Dominguez, CA), which was then cut to remove the incisor and to expose the mesial surface of the first molar using a wafering saw (Buehler, Inc., Lake Bluff, IL). The first molar was then ground using 400 grit silicon carbide paper from the mesial side to expose the interior of the tooth until the pulp, dentin, and enamel were visible simulataneously (see Figure 1). This interior surface was further smoothen by polishing with using a 1500 grit silicon carbide paper followed by ultramicrotoming with a 2.5 mm wide and 45° angle diamond knife (Diatome, Inc., Hatfield, PA) fitted on a MT 6000-XL ultra-microtome (Bal-Tec RMC, Inc., Tucson, AZ). Nanoindentation measurements on the specimen block (as seen in Figure 1) were carried out using a Triboscope™ nanoindentation unit (Hysitron, Inc., Minneapolis, MN) attached to Autoprobe CP scanning probe microscope (Veeco, Inc., Santa Barbara, CA; formerly Park Scientific Instruments, Inc.) in air. Regions that qualified for indentation measurements exhibited root-mean-square (rms) roughness < 10nm as measured by the nanoindenter (Berkovich diamond indentor with 80 nm tip radius). On every tooth, measurements were made on enamel, apical dentin, apical cementum, cervical dentin, and cervical cementum with 30 to 40 indentations on each region, at a contact depth of approximately of 100 nm and at least 3 contact radii apart.

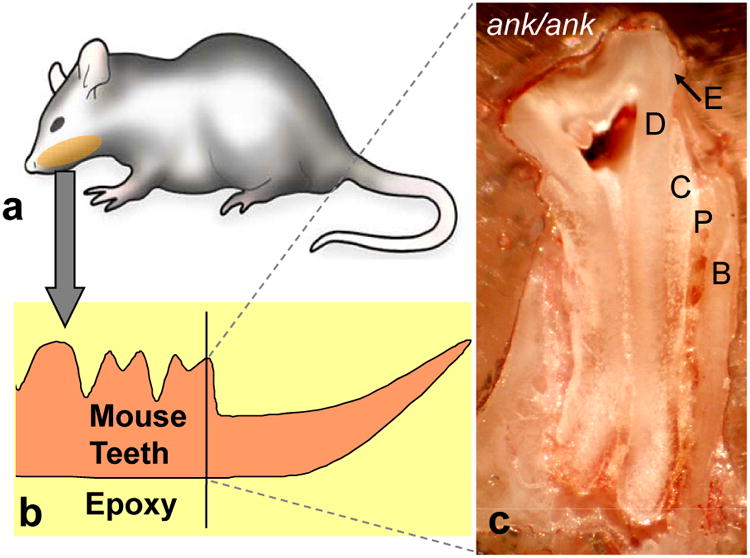

Figure 1.

Sample preparation for nanoindentation. Lower left mandible was extracted with all three molars, incisor, and alveolar bone intact (a) then mounted at room-temperature-cure epoxy (b). Incisor was removed by a diamond wafering saw. The internal cross-section of the first molar was then exposed by grinding (600 grit then 1500 grit SiC paper) from the mesial side until the pulp was visible. Final surface smoothing was prepared by an ultramicrotome using a diamond knife (c). Nomenclatures: E = enamel, D = dentin, C = cementum, P = periodontal ligament, and B = alveolar bone.

Structural and Composition Characterization – Electron Microscopy

Extracted lower right mandibles with incisors removed were dehydrated sequentially in 5%, 10%, 25%, 50%, 75% and 100% aqueous ethanol solutions for 30 minutes at each step. After dehydration, teeth were mounted in LR white epoxy (Ted Pella, Inc., Redding, CA). After grinding with 1500 grit SiC paper either from the mesial surface for TEM or sagitally for SEM to expose the interior of the molars revealing pulp, dentin and enamel simultaneously, ultra-sections were cut using a 2.5 mm wide and 45° angle diamond knife (Diatome, Inc., Hatfield, PA) fitted on a MT 6000-XL ultra-microtome (Bal-Tec RMC, Inc., Tucson, AZ) with incremental knife advancement settings ranging between 200 and 300 nm. Ultra-sections were collected using Cu grids coated with lacey-carbon support films (Ted Pella, Inc., Redding, CA) for transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analysis. These ultra-sections were not fixed, demineralized, or stained. For SEM the ultramicrotomed surface of the remaining block, sagitially cut, was coated with 1 nm of Au (682 PECS, Gatan Inc., Pleasanton, CA) then used for backscatter electron imaging by scanning electron microscopy (SEM). TEM imaging and selected area diffraction were performed on a Philips EM420 microscopy (FEI, Corp., Beaverton, OR, formerly Philips Electronics, Eindhoven, The Netherlands) with a LaB6 filament operating at 120 keV. Backscattered electron (BSE) imaging was performed using a JSM-7000F SEM (JEOL) at 30 keV (JEOL-USA, Inc., Peabody, MA). The depth of the gray scale in BSE images was 8 bit. Two hundred pixels from enamel, cervical dentin, and cervical cementum obtained from images of WT and ank/ank samples were plotted in histograms using gray scale depth to compare mineral density.

Results

TEM (Figure 2)

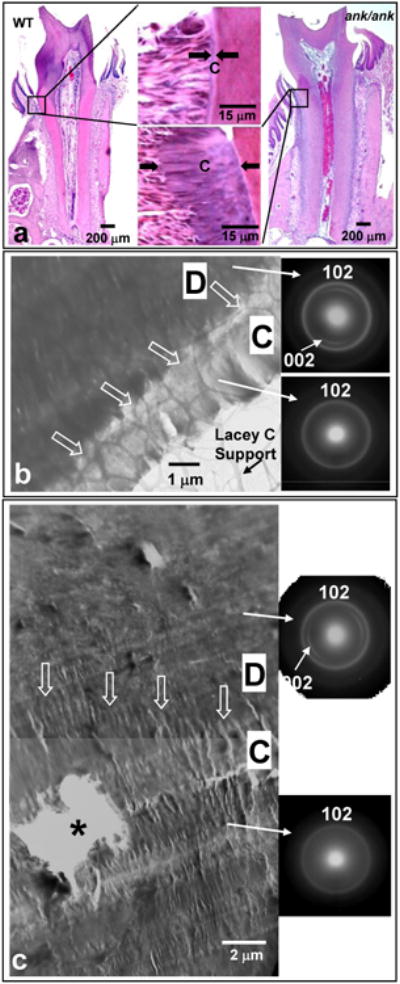

Figure 2.

Microscopy analyses of cervical cementum in WT and ank/ank animals. Histology images similar to those reported in Nociti et al [2] revealed more than a 10 fold increase in ank/ank cementum thickness compared to the WT sample (a). A similar difference between WT and ank/ank cementum was also observed at the TEM level as shown in (b) and (c). In both (b) and (c), the delineation between dentin and cementum are highlighted by white hollow arrow in the TEM images. The distinction between dentin and cementum was recognized based on the difference in the diffraction patterns. Dentin was identified by the textured 002 Hap reflections, which was absent in cementum due to a changed Hap crystal orientation. Diffraction patterns of cementum revealed no crystallographic difference between WT and ank/ank. See Figure 1 for nomenclature.

Bright field TEM images displaying cervical dentin and cementum simultaneously in WT and ank/ank samples are shown in Figures 2b and c, respectively. Selected area diffraction patterns taken in dentin and cementum in Figure 2b and c are shown as insets on the right side of the TEM images. Diffraction of dentin in WT and ank/ank samples displayed prominent Miller planes of (002) as arcs and (102) as rings of hydroxyapatite (Hap). However, diffraction of cementum regions displayed only (102) as prominent rings. Hence, the cementum-dentin junction (CDJ) as indicated by hollow arrows in Figures 2b and c could be identified based on the absence of (002). Cementum in Figure 2b appeared brighter than the adjacent dentin indicating that the WT cementum was less mineralized than the WT dentin. On the other hand, no contrast could be seen between dentin and cementum in Figure 2c indicating that the extent of mineralization in ank/ank cementum was comparable to that of the ank/ank dentin. Comparison of the TEM images in Figures 2b and c clearly revealed a dramatically wider ank/ank cementum than that of the WT sample. This observation was consistent with the histological observation in our previous study [2], which is also presented in Figure 2a for illustrative purposes. Furthermore, we noted that the ank/ank cementum in the cervical region appeared more like cellular cementum typically found in the apical region of the tooth root. As shown in Figure 2c, hole-like features possibly corresponding to spaces where cells would be, were observed in cervical ank/ank cementum. Such holelike features were not found in WT cervical cementum.

SEM (Figure 3)

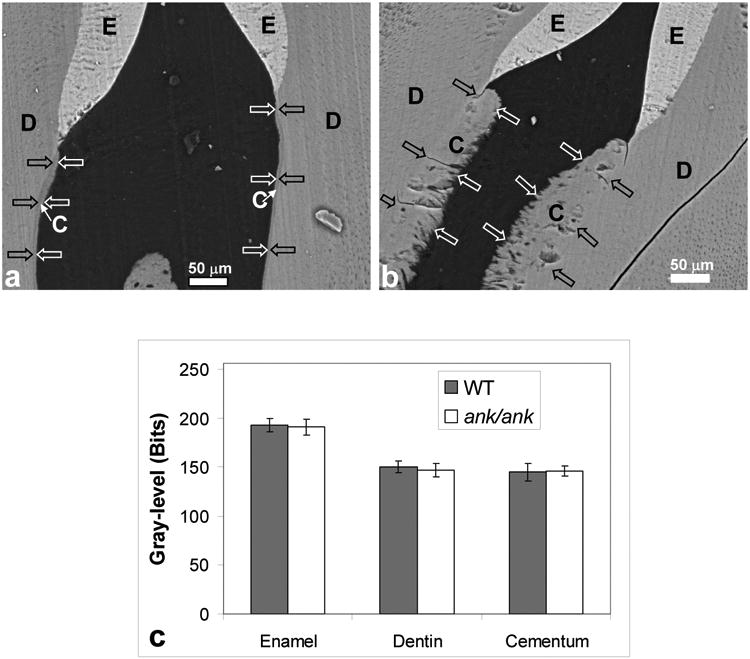

Figure 3.

SEM images of enamel, dentin, and cementum in the cervical regions in backscattered mode. In both WT (a) and ank/ank mice (b), enamel showed greater mass density than dentin and cementum, while no detectable differences were found between cementum and dentin regions in both WT and ank/ank tissues. The gray-level histogram in (c) revealed no significant differences in mass density between WT and ank/ank when the same tissues were compared. See Figure 1 for nomenclature.

A further comparison of mineral content between WT and ank/ank periodontal tissues was made further using SEM imaging in the backscatter (BSE) mode. The amount of backscattered electrons corresponds to the mass density of the material it is originating from, i.e. denser the material (both in terms of composition and elemental content), the brighter the image contrast as a result of more incident electrons scattered backwards from the sample towards the detector. The BSE images of 1st molars in the cervical regions in both groups are presented in Figures 3a and b. The primary source of contrast in these images was related to the difference in mineral density. In the images shown in Figures 3a and b, greater mineral density corresponded to a brighter region. Enamel, in both cases, being almost 100% mineralized, appeared the brightest, whereas cementum and dentin, both being composites of collagen/non-collagenous protein and mineral, appeared relatively darker. This imaging technique has been utilized to compare mineral contents between dental tissues [24]. A histogram representation of enamel, cervical dentin and cervical cementum comparing the brightness (or gray-level) of each region is represented Figure 3c. In both ank/ank and WT samples, an overall 23% decrease in brightness from enamel to dentin in gray-level was detected. A similar drop in gray-level was also detected when enamel was compared to cementum in both WT and ank/ank mutant teeth. However, no significant difference was found in the gray-level in cementum between ank/ank and WT samples. Likewise, neither enamel nor dentin yielded any significant difference when comparing the ank/ank tissue to WT counterparts. These gray-scale results could not be correlated to the percentage of mineral in each region as no appropriate standards exist for such materials. However, the lack of statistical difference in gray level between WT and ank/ank dental tissues qualitatively indicates that the degree of mineralization was not decreased by the mutation in the ank gene. Similar to TEM results in Figure 2c, no contrast was detected between cementum and dentin in the ank/ank sample. In addition, “holes” were observed in ank/ank tissue samples in cervical cementum, possibly corresponding to cell spaces in the ank/ank sample seen with TEM observation (Figure 3b).

Nanoindentation (Figure 4 & Table 1)

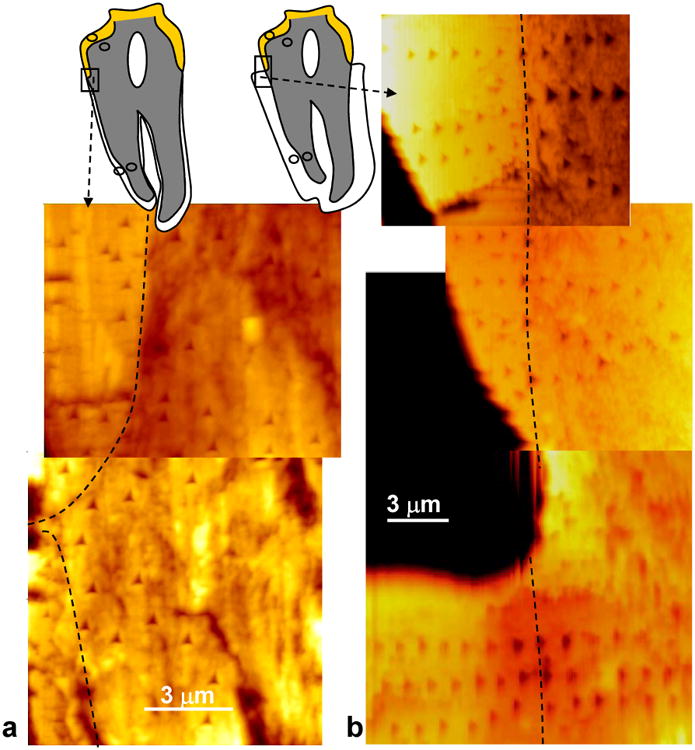

Figure 4.

Nanoindentation measurements were made in enamel, dentin (cervical & apical) and cementum (cervical & apical). Examples of sampling regions are shown in (a) for WT and (b) for ank/ank mutant tissues. Highlighted in the rectangular outlines are indentation profiles taken from DEJ and DCJ in the cervical regions. Dotted lines in (a) and (b) denote DCJ. The circled regions are the additional sampled regions of nanoindentation.

Table 1.

Tabulated hardness (H) and elastic modulus (Er) of WT and ank/ank mouse dental tissues.

| Wild-Type (n = 6) | Ank (n = 5) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Er (GPa) | H(GPa) | Er (GPa) | H(GPa) | |

| Enamel | 87 + 3 | 3.1 + 0.3 | 86 + 2 | 3.0 + 0.3 |

| Dentin (Cervical) | 28 + 3 | 1.1 + 0.2 | 28 + 2 | 1.0 + 0.3 |

| Cementum (Cervical) | 26 + 2 | 0.9 + 0.2 | 23 + 2 | 0.7 + 0.1 |

| Dentin (Apical) | 26 + 3 | 0.9 + 0.2 | 26 + 2 | 0.9 + 0.2 |

| Cementum (Apical) | 24 + 3 | 0.8 + 0.2 | 22 + 3 | 0.7 + 0.1 |

Mechanical properties of the mineralized dental tissues were assessed by the nanoindentation measurements. Nanoindentation characterization was performed on enamel, dentin (cervical and apical) and cementum (cervical and apical). Examples of indentation profiles performed in the cervical regions of both WT and ank are shown in Figure 4. A Student's t test with greater than 95% confidence level indicated no difference in reduced elastic modulus (Er)and hardness (H) between WT cervical cementum (Er = 26+2 GPa, H = 0.9+0.2 GPa) and ank/ank cervical cementum (Er = 23+2 GPa, H = 0.7+0.1 GPa), as shown in Table 1. Likewise, no significant difference was detected in apical dentin, cervical dentin, apical cementum, and cervical cementum between WT and ank/ank (see Table 1). Each reported value was represented by at least 180 measurements over at least 5 teeth.

Discussion

Two key components necessary for monitoring successful regeneration of cementum are: 1) identifying and demonstrating factors that stimulate formation of cementum (morphogenesis and mineralization), and 2) proper techniques to characterize whether or not the formed tissues are, in fact, sound. Given our recent demonstration that abundant cementum is formed as a result of decreased extracellular pyrophosphate levels via ank gene mutation [2], we continued studies to characterize the quality of the tissue in terms of mechanical properties and electron microscopy. These types of characterization were carried out without performing demineralization of the dental tissues so that the data reflected tissues in their natural state as much as possible. Given the small dimensions of mouse teeth, nanoindentation was chosen as a viable method to probe the mechanical properties of the individual dental tissues. Mouse molars were prepared by microtome to characterize the mineral phase. In terms of mechanical integrity, cementum in ank/ank mice was comparable to that of WT. In addition, the extent of mineralization and the structure of the ank/ank cementum were also determined in comparison to that of WT as characterized by SEM and TEM. Taken together, these results support the conclusion that, despite the rapid and abundant growth of cementum as a result of mutation in the ANK protein, the structural and mechanical integrity remain unaltered compared to the WT controls.

The results for the mechanical and structural properties of cementum in ank/ank mice are interesting. As previously observed by histology [2] and confirmed here by TEM analysis, the thick cementum formed in ank/ank mice is remarkably cellular in the region of cervical cementum, which is normally acellular [25]. We previously hypothesized that the enhanced formation of cementum in ank/ank mice resulted in cells becoming entrapped in the rapidly expanding cementum matrix, and further that the swift deposition of matrix would result in decreased mineral density, i.e. an increase in “unmineralized” cementum-like tissue. However, the sum of the results presented here demonstrates that the rapidly formed cementum of the ank/ank mice is statistically indistinguishable from WT in terms of mechanical and mineral properties. A possible explanation for these findings is that there might be a sufficient concentration of Pi and Ca2+ in local region to promote physiological mineralization.

In addition to the physical-chemical effects of altered PPi levels, potential cellular effects may also play a role in the cementum phenotype observed in ank/ank mice. Evidence has accumulated for a signaling role for inorganic phosphate (Pi) [26-30], and more recently for PPi [7, 31, 32]. For example, existing data indicate that Pi may act as a signaling molecule by altering expression of genes involved in mineral homeostasis [27-29]. In concert with disrupted metabolism and altered Pi/PPi noted in the ank/ank mice, it is conceivable that cells within the periodontal ligament region are affected by changes in phosphate homeostasis and thus contribute to the cementum phenotype noted in these mice. The implications and mechanisms by which Pi affects cementoblast behavior are currently being studied.

Developing predictable therapies for restoring the damaged periodontium is a primary focus for many researchers, at both the basic science and clinical level. Successful regeneration of the periodontium requires formation of new alveolar bone, a functional PDL, as well as new a cementum to anchor the teeth. The studies presented here provide further understanding of the mechanisms governing cementum formation, and will ultimately be significant in defining optimal conditions for promoting cementum regeneration.

Conclusions

Understanding the factors controlling mineralization of cementum is critical to developing therapeutic strategies to regenerate periodontium. Our study of the ank/ank mouse model has demonstrated that deactivating the transport of PPi from intracellular to extracellular matrix resulted in faster forming and more abundant cementum relative to the normal tissue [2]. This study on ank/ank mouse teeth further demonstrates that the faster growing cementum yielded comparable structural and mechanical properties as revealed by imaging and functional studies carried out by electron microscopy and nanoindentation, respectively. These results indicate that, further studies targeted at designing therapies that can control local PPi levels, may provide a therapy for regenerating periodontal tissues.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thank Ms. Erica Swanson for managing the mice for this study. The authors are also grateful for Drs. Sunao Sato and Francisco H. Nociti Jr. for their assistance in tissue preparation. GEMSEC shared experimental facilities (an NSF-MRSEC) at the UW were utilized to carry out structural and mechanical property characterization. This study was supported by NIDCR/NIH DE015109 and DE09532.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ho AM, Johnson MD, Kingsley DM. Role of the mouse ank gene in control of tissue calcification and arthritis. Science. 2000;289:265–270. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5477.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nociti FH, Jr, Berry JE, Foster BL, Gurley KA, Kingsley DM, Takata T, Miyauchi M, Somerman MJ. Cementum: a phosphate-sensitive tissue. Journal of Dental Research. 2002;81:817–821. doi: 10.1177/154405910208101204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Polimeni G, Xiropaidis AV, Wikesjo UM. Biology and principles of periodontal wound healing/regeneration. Periodontol. 2006;200041:30–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2006.00157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ramseier CA, Abramson ZR, Jin Q, Giannobile WV. Gene therapeutics for periodontal regenerative medicine. Dent Clin North Am. 2006;50:245–63. ix. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2005.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abukawa H, Papadaki M, Abulikemu M, Leaf J, Vacanti JP, Kaban LB, Troulis MJ. The engineering of craniofacial tissues in the laboratory: a review of biomaterials for scaffolds and implant coatings. Dent Clin North Am. 2006;50:205–16. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2005.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakahara T. A review of new developments in tissue engineering therapy for periodontitis. Dent Clin North Am. 2006;50:265–76. ix–x. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harmey D, Hessle L, Narisawa S, Johnson KA, Terkeltaub R, Millan JL. Concerted regulation of inorganic pyrophosphate and osteopontin by akp2, enpp1, and ank: an integrated model of the pathogenesis of mineralization disorders. Am J Pathol. 2004;164:1199–209. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63208-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murshed M, Harmey D, Millan JL, McKee MD, Karsenty G. Unique coexpression in osteoblasts of broadly expressed genes accounts for the spatial restriction of ECM mineralization to bone. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1093–104. doi: 10.1101/gad.1276205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takeda E, Yamamoto H, Nashiki K, Sato T, Arai H, Taketani Y. Inorganic phosphate homeostasis and the role of dietary phosphorus. J Cell Mol Med. 2004;8:191–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2004.tb00274.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Terkeltaub RA. Inorganic pyrophosphate generation and disposition in pathophysiology. American Journal of Physiology - Cell Physiology. 2001;281:C1–C11. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.281.1.C1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kinney JH, Habelitz S, Marshall SJ, Marshall GW. The importance of intrafibrillar mineralization of collagen on the mechanical properties of dentin. J Dent Res. 2003;82:957–61. doi: 10.1177/154405910308201204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rho JY, Mishra SR, Chung K, Bai J, Pharr GM. Relationship Between Ultrastructure and the Nanoindentation Properties of Intramuscular Herring Bones. Annals of Biomedical Engineering. 2001;29:1082–1088. doi: 10.1114/1.1424913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu J, Rho JY, Mishra SR, Fan Z. Atomic force microscopy and nanoindentation characterization of human lamellar bone prepared by microtome sectioning and mechanical polishing technique. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research. 2003;67A:719–726. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.10109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ho SP, Balooch M, Marshall SJ, Marshall GW. Local properties of a functionally graded interphase between cementum and dentin. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2004;70:480–489. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lippert F, Parker DM, Jandt KD. Susceptibility of deciduous and permanent enamel to dietary acid-induced erosion studied with atomic force microscopy nanoindentation. Eur J Oral Sci. 2004;112:61–66. doi: 10.1111/j.0909-8836.2004.00095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lippert F, Parker DM, Jandt KD. In vitro demineralization/remineralization cycles at human tooth enamel surfaces investigated by AFM and nanoindentation. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2004;280:442–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2004.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ge J, Cui FZ, Wang XM, Feng HL. Property variations in the prism and the organic sheath within enamel by nanoindentation. Biomaterials. 2005;26:3333–3339. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.07.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barbour ME, Parker DM, Allen GC, Jandt KD. Human enamel erosion in constant composition citric acid solutions as a function of degree of saturation with respect to hydroxyapatite. J Oral Rehabil. 2005;32:16–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2004.01365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ho SP, Sulyanto RM, Marshall SJ, Marshall GW. The cementum-dentin junction also contains glycosaminoglycans and collagen fibrils. J Struct Biol. 2005;151:69–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barbour ME, Finke M, Parker DM, Hughes JA, Allen GC, Addy M. The relationship between enamel softening and erosion caused by soft drinks at a range of temperatures. J Dent. 2006;34:207–213. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hairul Nizam BR, Lim CT, Chang HK, Yap AU. Nanoindentation study of human premolars subjected to bleaching agent. J Biomech. 2005;38:2204–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2004.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Balooch G, Marshall GW, Marshall SJ, Warren OL, Asif SA, Balooch M. Evaluation of a new modulus mapping technique to investigate microstructural features of human teeth. J Biomech. 2004;37:1223–1232. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2003.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fong H, White SN, Paine ML, Luo W, Snead ML, Sarikaya M. Enamel structure properties controlled by engineered proteins in transgenic mice. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18:2052–2059. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.11.2052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mahoney EK, Rohanizadeh R, Ismail FS, Kilpatrick NM, Swain MV. Mechanical properties and microstructure of hypomineralised enamel of permanent teeth. Biomaterials. 2004;25:5091–100. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.02.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nanci A, Somerman MJ. Periodontium. In: Nanci A, editor. Ten Cate's Oral Histology. St. Louis: Mosby; 2003. pp. 240–274. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adams CS, Mansfield K, Perlot RL, Shapiro IM. Matrix regulation of skeletal cell apoptosis. Role of calcium and phosphate ions. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:20316–20322. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006492200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beck GR., Jr Inorganic phosphate as a signaling molecule in osteoblast differentiation. J Cell Biochem. 2003;90:234–243. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Foster BL, Nociti FH, Jr, Swanson EC, Matsa-Dunn D, Berry JE, Cupp CJ, Zhang P, Somerman MJ. Regulation of cementoblast gene expression by inorganic phosphate in vitro. Calcif Tissue Int. 2006;78:103–12. doi: 10.1007/s00223-005-0184-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jono S, McKee MD, Murry CE, Shioi A, Nishizawa Y, Mori K, Morii H, Giachelli CM. Phosphate regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell calcification. Circ Res. 2000;87:E10–17. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.7.e10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rutherford RB, Foster BL, Bammler T, Beyer RP, Sato S, Somerman MJ. Extracellular phosphate alters cementoblast gene expression. J Dent Res. 2006;85:505–509. doi: 10.1177/154405910608500605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harmey D, Johnson KA, Zelken J, Camacho NP, Hoylaerts MF, Noda M, Terkeltaub R, Millan JL. Elevated skeletal osteopontin levels contribute to the hypophosphatasia phenotype in Akp2(-/-) mice. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21:1377–1386. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.060619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Addison WN, Azari F, Sorensen ES, Kaartinen MT, McKee MD. Pyrophosphate inhibits mineralization of osteoblast cultures by binding to mineral, up-regulating osteopontin, and inhibiting alkaline phosphatase activity. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(21):15872–15883. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701116200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]